Abstract

This study describes the roles of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in providing care to specialist physicians’ patients.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) play key roles in expanding access to primary care, but their involvement in specialty care is not well described. Given concerns about the limited supply of specialist physicians, increasing incorporation of NPs and PAs into collaborative specialist practices could be a strategy for improving access. Prior studies described the frequency of NPs and PAs practicing in specialty practices, and quantified the volume of care by NPs and PAs for surgical outpatients. However, to our knowledge, no study has described trends in specialist physician visits in which NPs and PAs provide care. We hypothesized that NPs and PAs increasingly are providing care to specialist physicians’ patients, and that this growth is primarily for routine follow-up.

Methods

Administered by the National Center for Health Statistics, the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) samples office visits with physicians to create nationally representative estimates of outpatient care (n = 473 132 visits from 2001 to 2013). We identified visits to specialist physicians and divided these into surgical and medical specialist physicians. We first examined unadjusted trends from 2001 to 2013 in the percentage of visits with NP or PA involvement (ie, an NP or PA saw the patient with a physician or an NP or PA saw the patient without a physician), using multiyear intervals owing to sample size. We then examined visit characteristics associated with higher likelihood of NP or PA involvement in recent years (2010-2013), using a logistic regression model controlling for all listed visit and patient characteristics (Table) to generate adjusted percentages. The University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protection Office judged this study exempt from review.

Table. Adjusted Percentage of Visits Involving NPs and PAs by Visit and Patient Characteristics, 2010-2013.

| Characteristic | Specialist Physician Visits, 2010-2013 (n = 78 431) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Visits With Characteristic (Survey Weighted %) |

Adjusted % of Visits Involving NPs or PAs Among Visits With Specified Characteristica | P Valuea | |

| All visits | 78 431 (100) | 6.3 | NA |

| Visit Characteristics | |||

| Visit type | .008 | ||

| Return | 61 328 (79.1) | 6.7 | |

| New | 17 103 (20.9) | 4.8 | |

| Visit reason | .004 | ||

| New problem | 19 960 (26.8) | 7.2 | |

| Chronic problem, routine | 34 767 (42.2) | 4.9 | |

| Chronic problem, flare | 8231 (10.9) | 6.4 | |

| Presurgical or postsurgical | 9025 (11.8) | 9.3 | |

| Preventive care | 5392 (7.0) | 7.1 | |

| Missing | 1056 (1.4) | 5.0 | |

| Specialty | .86 | ||

| Cardiology | 3236 (4.1) | 5.4 | |

| Dermatology | 2949 (5.9) | 8.3 | |

| Otorhinolaryngology | 2995 (3.3) | 8.5 | |

| General surgery | 2482 (2.9) | 4.0 | |

| Neurology | 3396 (2.2) | 7.9 | |

| Ophthalmology | 3050 (8.2) | 6.2 | |

| Orthopedics | 2714 (8.4) | 7.3 | |

| Urology | 2965 (3.2) | 7.2 | |

| Other surgical specialty | 18 479 (18.7) | 6.3 | |

| Other medical specialty | 36 165 (43.2) | 5.9 | |

| Patient Characteristics | |||

| Patient age, y | .006 | ||

| 0-17 | 6784 (8.0) | 6.8 | |

| 18-64 | 44 170 (57.1) | 7.1 | |

| ≥65 | 27 477 (34.9) | 5.1 | |

| Sex | .65 | ||

| Female | 42 693 (55.3) | 6.4 | |

| Male | 35 738 (44.7) | 6.2 | |

| Race/ethnicity | .34 | ||

| Hispanic | 6450 (9.4) | 6.4 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5944 (8.1) | 7.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 62 670 (77.9) | 6.2 | |

| Other | 3367 (4.6) | 5.6 | |

| Chronic conditionsb | .001 | ||

| Missing | 2531 (3.0) | 4.2 | |

| None | 28 647 (36.8) | 5.6 | |

| 1 | 22 785 (28.0) | 5.6 | |

| 2-3 | 18 809 (24.7) | 7.2 | |

| ≥4 | 5659 (7.5) | 10.6 | |

| Insurance type | <.001 | ||

| Medicaid | 7193 (8.8) | 6.7 | |

| Medicare | 23 486 (29.9) | 6.8 | |

| Other/unknown | 6366 (7.4) | 4.9 | |

| Private | 37 183 (48.4) | 6.5 | |

| Uninsured | 4203 (5.5) | 3.0 | |

| US Census region | <.001 | ||

| Northeast | 12 808 (20.2) | 9.6 | |

| Midwest | 17 727 (17.4) | 4.0 | |

| South | 27 130 (38.5) | 6.8 | |

| West | 20 766 (24.0) | 4.2 | |

| Location | .74 | ||

| Rural | 6796 (6.3) | 6.9 | |

| Urban | 71 635 (93.7) | 6.3 | |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; NP, nurse practitioner; PA, physician assistant.

Adjusted percentages were estimated using visit-level multivariable logistic regression with a dependent binary variable of PA and NP involvement in visits to specialist physicians in 2010 to 2013. Regression models adjusted for all listed variables and accounted for clustering and weights in the multistage survey design. After fitting the model, we used predictive margins to generate adjusted percentages for each characteristic. P values were estimated using Wald tests of each indicated variable across all subcategories in the multivariable logistic regression model.

Chronic conditions include arthritis, asthma, cancer, cerebrovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure, congestive heart failure, depression, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, obesity, and osteoporosis.

Results

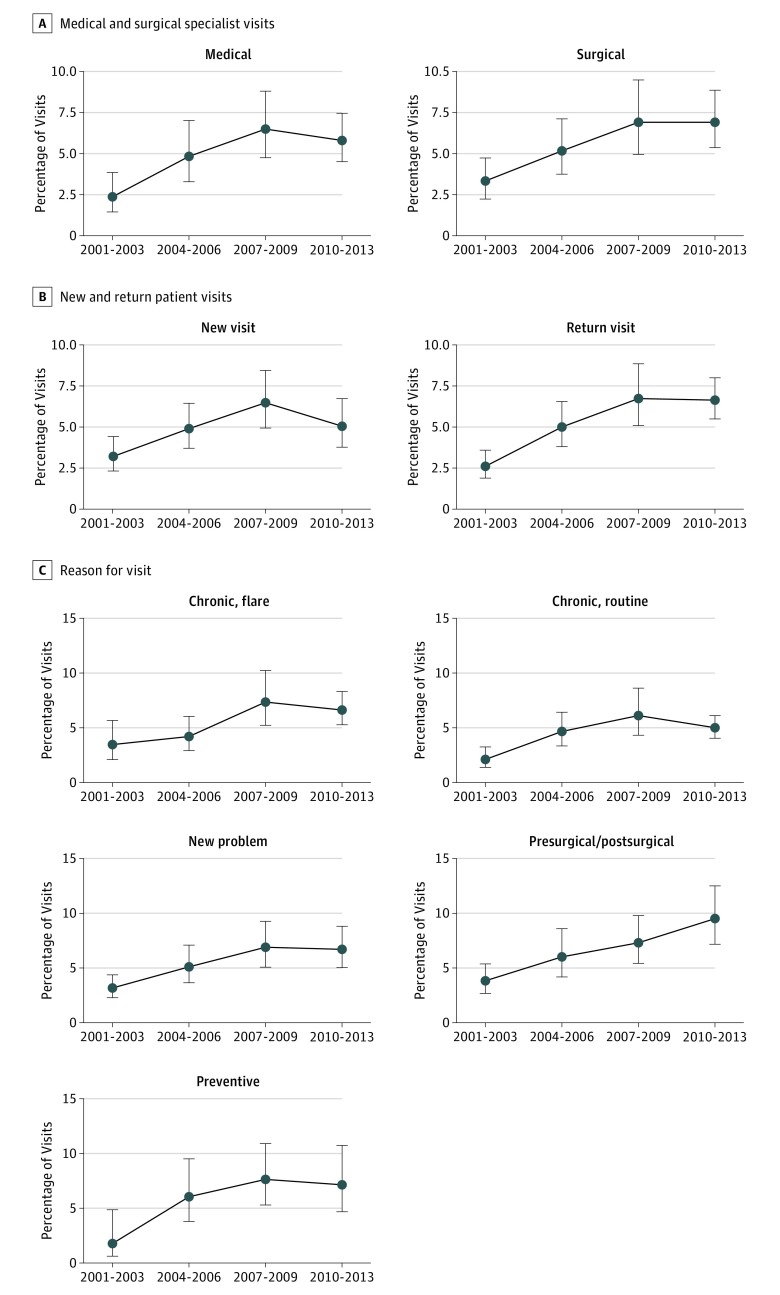

Among visits to surgical and medical specialist physicians, the proportion involving an NP or PA increased from 3.3% in 2001 to 2003 to 6.9% in 2010 to 2013 (P = .001) and 2.4% to 5.8% (P < .001), respectively (Figure, A). Similar growth in NP or PA visits was observed for new and return visits (Figure, B) and for all visit reasons (ie, acute problem, routine chronic, perioperative) (Figure, C). Among visits with NPs or PAs, the proportion of visits where the patient did not also see a physician increased from 12.3% to 21.4% (P = .004).

Figure. Trends in Care by Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physician Assistants (PAs) to Specialist Physician Patients, 2001-2013.

A, Unadjusted trends from 2001 to 2013 in visits with NPs and PAs as a percentage of all outpatient visits to medical and surgical specialist physicians.B, The same trends as a percentage of all “new” and “return” patient visits, respectively. C, The same trends by reason for visit. The P value for linear growth by bivariate survey-weighted logistic regression is .001 or less for all subcategories except the “preventive” visit reason, where P = .01. Error bars indicate 95% CIs incorporating survey weights and clustering from the multistage sampling design of National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS).

Adjusting for other visit and patient factors, the proportion of 2010-2013 visits involving an NP or PA varied significantly by visit reason (4.9% of routine chronic visits vs 9.3% of presurgical and postsurgical visits; P = .004 for category), patient comorbidity (10.6% of visits among patients with ≥4 chronic conditions vs 5.6% with no chronic conditions; P = .001 for category), and region (4% of visits in the Midwest vs 9.6% in the Northeast; P < .001 for category) (Table). The adjusted proportion of 2010-2013 visits involving an NP or PA ranged from 4.0% to 8.5% across specific specialties identified in the Table (P = .86).

Discussion

Involvement of NPs and PAs in the care of patients of specialist physicians increased over the past decade, but growth slowed in recent years, and visits involving NPs or PAs remain a small proportion of overall specialty visits. Contrary to our hypothesis, growth was observed in unadjusted analysis not only for return and routine visits, but also for new patients and acute visits. Rates of NPs or PAs seeing patients without a physician also seeing the patient increased. In adjusted analysis, NPs or PAs were disproportionately involved in care of patients with greater medical complexity, requiring further work to understand if this reflects team-based care, coding artifact, or other explanations. These findings are particularly notable given that NPs and PAs in specialty care receive shorter formal training than specialist physicians, with specialty-specific training entirely on-the-job in some fields.

Our study is limited in that NAMCS samples visits to nonfederal office-based physicians and reflects only care that occurs among NPs and PAs sharing rosters with physicians. As such, our results may underestimate total involvement of NPs and PAs in specialty care but should accurately reflect trends in NPs and PAs providing care in conjunction with specialist physicians. Our findings have implications for the specialty workforce, and the impact on access to specialty care and its quality should be evaluated.

References

- 1.Hooker RS, McCaig LF. Use of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in primary care, 1995-1999. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(4):231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and electronic communication. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IHS Inc. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2014-2025, 2016 Update. Prepared for the Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington, DC: IHS Inc; 2016.

- 4.Park M, Cherry D, Decker SL. Nurse practitioners, certified nurse midwives, and physician assistants in physician offices. NCHS Data Brief. 2011;(69):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan PA, Hooker RS. Choice of specialties among physician assistants in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):887-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salibian AA, Mahboubi H, Patel MS, et al. . The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: PAs and NPs in outpatient surgery. JAAPA. 2016;29(5):47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]