Key Points

Question

How do emergency departments set chargemaster prices for services, and how do these practices affect patients?

Findings

In this analysis of Medicare billing records from 2707 US hospitals in 2013, different emergency departments charged between 1.0 and 12.6 times what Medicare paid for the services. Excess charges, or “markups,” on specific services were greater when performed by an emergency medicine physician compared with an internal medicine physician.

Meaning

Further legislation is needed to protect uninsured and out-of-network patients from excess charges in the emergency department.

Abstract

Importance

Uninsured and insured but out-of-network emergency department (ED) patients are often billed hospital chargemaster prices, which exceed amounts typically paid by insurers.

Objective

To examine the variation in excess charges for services provided by emergency medicine and internal medicine physicians.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective analysis was conducted of professional fee payment claims made by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for all services provided to Medicare Part B fee-for-service beneficiaries in calendar year 2013. Data analysis was conducted from January 1 to July 31, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Markup ratios for ED and internal medicine professional services, defined as the charges submitted by the hospital divided by the Medicare allowable amount.

Results

Our analysis included 12 337 emergency medicine physicians from 2707 hospitals and 57 607 internal medicine physicians from 3669 hospitals in all 50 states. Services provided by emergency medicine physicians had an overall markup ratio of 4.4 (340% excess charges), which was greater than the markup ratio of 2.1 (110% excess charges) for all services performed by internal medicine physicians. Markup ratios for all ED services ranged by hospital from 1.0 to 12.6 (median, 4.2; interquartile range [IQR], 3.3-5.8); markup ratios for all internal medicine services ranged by hospital from 1.0 to 14.1 (median, 2.0; IQR, 1.7-2.5). The median markup ratio by hospital for ED evaluation and management procedure codes varied between 4.0 and 5.0. Among the most common ED services, laceration repair had the highest median markup ratio (7.0); emergency medicine physician review of a head computed tomographic scan had the greatest interhospital variation (range, 1.6-27.7). Across hospitals, markups in the ED were often substantially higher than those in the internal medicine department for the same services. Higher ED markup ratios were associated with hospital for-profit ownership (median, 5.7; IQR, 4.0-7.1), a greater percentage of uninsured patients seen (median, 5.0; IQR, 3.5-6.7 for ≥20% uninsured), and location (median, 5.3; IQR, 3.8-6.8 for the southeastern United States).

Conclusions and Relevance

Across hospitals, there is wide variation in excess charges on ED services, which are often priced higher than internal medicine services. Our results inform policy efforts to protect uninsured and out-of-network patients from highly variable pricing.

This study compares Medicare charges for common physician services conducted in emergency departments vs those of internal medicine physicians in the United States.

Introduction

Patients presenting to different emergency departments (ED) can face widely varying charges for similar care. Hospitals use chargemasters (list of services and their charges) to compile each patient's bill, but the actual payment depends on the patient’s insurance type and network status. In-network patients and their insurers usually pay discounted amounts, whereas uninsured and out-of-network patients may be liable for the full hospital charges. In 2012, the 50 hospitals in the United States with the highest markups charged patients at least 9.2 times what the Medicare program would pay for care.

Excess charges, or “markups,” on medical services can impose a significant financial burden on uninsured and out-of-network patients. Medical bills are the leading cause of bankruptcy and contribute to some patients electing to avoid necessary care. Understanding markups in the ED is especially important because uninsured and out-of-network patients commonly seek care in the ED, and the often acute nature of the medical services needed prevents them from comparison shopping. Little is known, however, about the national variation in markups on ED services and how they may differ from those in other hospital departments. In this study, we used physician payment data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to study the variation in markups on ED professional services and in relation to markups in internal medicine. We also examined the association between the level of markup and the characteristics of the hospitals and their patient populations.

Methods

We compared physician charges with what the Medicare program would pay emergency medicine physicians for the same service (ie, the level of excess charges, or markup). We then aggregated the physicians by their primary hospital affiliations and analyzed the markups on ED services at the hospital level and relative to markups on internal medicine services. Finally, we analyzed the factors associated with ED and internal medicine markups using multivariable linear regression models that included characteristics of the hospitals and their patient populations. This study was exempted by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board as not being human subjects research.

Data Sets

We used the 2013 Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Physician and Other Supplier, which includes claims for all services that physicians performed for Medicare Part B fee-for-service beneficiaries. For patient privacy reasons, the data set excluded services provided to fewer than 10 beneficiaries by a single physician. We included claims billed by emergency medicine and internal medicine physicians in a hospital facility and excluded services performed in an office setting. Claims were linked using the National Physician Identifier to the Physician Compare database to identify each physician’s primary hospital affiliation. The 2013 American Hospital Association database (https://www.ahadataviewer.com/additional-data-products/AHA-Survey) was used to identify the characteristics of the EDs, including size, urban/rural status, teaching status, for-profit status, regional location, and safety-net hospital status. Safety-net hospitals included all public hospitals, as well as private hospitals with a Medicaid utilization rate, defined as Medicaid hospital days divided by total hospital days, greater than 1 SD above the mean rate in its state. Lastly, we estimated the prevalence of poverty, uninsured status, and minority populations in the zip code where each hospital is located, using data from the 2013 American Community Survey (US Census Bureau; https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html).

Markup Ratios

We assessed the level of excess charges using markup ratios, which is the ratio of the billed charges to the Medicare allowable amount. For example, a markup ratio of 3.5 means that for a service with a $100 Medicare-allowable amount, the hospital charges $350, or 250% in excess charges. This approach is consistent with previous literature using Medicare payment rates as a benchmark to compare charges across specialties and regions. The Medicare-allowable amount is the sum of what Medicare pays, the deductible and coinsurance amount that the beneficiary is responsible for paying, and any amount that a third party is responsible for paying. Consistent with previous work, we assumed that these charges are the maximum potential amounts billed to uninsured and out-of-network patients.

Emergency medicine and internal medicine physicians bill for professional fees to either perform a service or interpret procedures performed by other medical specialties. The Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data lists charges billed to Medicare by each physician as well as the Medicare-allowable amount for each Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code. Charges and Medicare-allowable amounts for each physician have been adjusted for modifiers that in some instances indicate a higher or lower intensity or complexity of service. We excluded HCPCS codes describing services provided by emergency medicine physicians outside the ED setting, including those from inpatient care and office visits. For emergency medicine and internal medicine, we defined each hospital’s markup ratio as the aggregated physician professional fee charges submitted to Medicare divided by the aggregated Medicare-allowable amounts in 2013.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the variation in markup ratios for all ED and internal medicine services and individual HCPCS codes at the hospital level, focusing on the services with the greatest national total Medicare-allowable amounts. The most common ED services included levels 1 to 5 evaluation and management codes for clinical evaluation and decision making (HCPCS codes 99281-99285); common procedures performed by emergency medicine physicians, including wound care (code 97597), laceration repair (codes 12001-12002), management and supervision of oxygen chamber therapy (code 99183), debridement (codes 11042, 11043, 11045, and 15271), critical care (codes 99291-99292), intubation (code 31500), insertion of an intravenous catheter (code 36556), and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (code 92950); and emergency medicine physician professional fees for interpreting studies performed by other physicians, including chest radiographs (codes 71010 and 71020), electrocardiograms (codes 93010 and 93042), and computed tomographic scans of the head (code 70450). For common ED services also performed by internal medicine physicians in other hospital settings, we performed a direct comparison of markups in hospitals that billed from both departments.

We performed multivariable linear regression analysis to study the association between the ED markup ratios and characteristics of the hospitals and their patient populations. A 1-U increase in the ED markup ratio means that, for every $100 in Medicare-allowable amount billed, the ED charged an additional $100. Data analysis was conducted from January 1 to July 31, 2016. All analyses were performed using Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

We identified 12 337 emergency medicine physicians affiliated with 2707 EDs and 57 607 internal medicine physicians affiliated with 3669 hospitals in all 50 states that billed for Medicare Part B services in 2013. The characteristics of the EDs were similar to those of hospitals billing internal medicine services in the United States: 49.5% were located within urban hospitals, 34.6% were in teaching hospitals, 18.2% were for-profit institutions, and 59.3% were in hospitals with fewer than 200 beds (Table 1). Approximately 1 in 4 (22.9%) EDs was located in a zip code in which more than 20% of the population was uninsured.

Table 1. Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Department, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Emergency (n = 2707) |

Internal Medicine (n = 3669) |

|

| Hospital size, beds | ||

| <200 | 1606 (59.3) | 2372 (64.6) |

| 200-399 | 697 (25.7) | 844 (23.0) |

| ≥400 | 404 (14.9) | 453 (12.3) |

| For-profit | 494 (18.2) | 677 (18.5) |

| Urban | 1340 (49.5) | 1750 (47.7) |

| Academic | 937 (34.6) | 1205 (32.8) |

| Population living in poverty, % | ||

| <10 | 585 (21.6) | 778 (21.2) |

| 10-19 | 1115 (41.2) | 1978 (53.9) |

| ≥20 | 1007 (37.2) | 730 (19.9) |

| Uninsured population, % | ||

| <10 | 653 (24.1) | 914 (24.9) |

| 10-19 | 1434 (53.0) | 1978 (53.9) |

| ≥20 | 620 (22.9) | 730 (19.9) |

| Race/ethnicity, % | ||

| ≥20 African American | 581 (21.5) | 713 (19.4) |

| ≥20 Hispanic | 606 (22.4) | 705 (19.2) |

| Safety-net hospital | 492 (18.2) | 680 (19) |

Nationwide, services provided by emergency medicine physicians to Medicare Part B fee-for-service beneficiaries totaled $4 billion in charges and $898 million in Medicare-allowable amounts, representing an overall markup ratio of 4.4 (340% excess charges). By contrast, the overall markup ratio for all services provided by internal medicine physicians was 2.1 (110% excess charges). Markup ratios for common ED services varied widely by procedure code and hospital (Table 2). Among the evaluation and management codes, which accounted for the majority of professional fees paid to emergency medicine physicians, the median markup by hospital for level 1 to 5 visits varied from 4.0 to 5.0. Laceration repair had the highest median markup ratio (median by hospital, 7.0; range, 2.0-15.0), and interpretation of a computed tomographic scan of the head had the greatest interhospital variation, ranging between 1.6 and 27.7. Markup ratios in the ED were generally higher than those in internal medicine for common services performed in both departments (Table 3).

Table 2. Markup Ratios by Hospital for Common Procedure Codes Billed by Emergency Medicine Physiciansa .

| Service | National Total Medicare-Allowable Amount in 2013, $b | Markup Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | 25th Percentile | Median | 75th Percentile | Maximum | ||

| Evaluation and Management Services | ||||||

| Level 5 visit (n = 2526) | 528M | 1.0 | 3.4 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 10.5 |

| Level 4 visit (n = 2577) | 174M | 1.0 | 3.3 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 11.6 |

| Level 3 visit (n = 2538) | 48.6M | 1.1 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 16.4 |

| Level 2 visit (n = 920) | 2.79M | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 14.2 |

| Level 1 visit (n = 125) | 98.7K | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.6 | 6.3 | 13.9 |

| Other ED services | ||||||

| Critical care (n = 2004) | 110M | 1.1 | 3.2 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 23.8 |

| Interpretation of ECG (n = 1891) | 12.8M | 1.1 | 4.4 | 6.0 | 7.8 | 20.0 |

| Management and supervision of oxygen chamber therapy (n = 161) | 6.35M | 1.0 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 9.5 |

| Debridement (n = 171) | 4.03M | 1.1 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 9.5 |

| Intubation (n = 543) | 2.31M | 1.0 | 3.4 | 4.6 | 6.0 | 10.4 |

| Insertion of IV (n = 286) | 1.17M | 1.4 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 18.1 |

| Wound care (n = 143) | 752K | 1.1 | 3.3 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 17.5 |

| Interpretation of chest radiograph (n = 285) | 659K | 1.0 | 3.8 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 16.3 |

| CPR (n = 104) | 493K | 1.6 | 3.4 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 9.6 |

| Laceration repair (n = 176) | 186K | 2.0 | 5.2 | 7.0 | 9.2 | 15.0 |

| Head CT interpretation (n = 12) | 130K | 1.6 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 27.7 |

Abbreviations: CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; ED, emergency department; K, thousand; M, million.

Ranked by national total Medicare-allowable amounts paid to emergency medicine physicians in 2013 (n = 2707).

Hospital numbers and national Medicare-allowable amounts are limited to hospitals with 1 or more physician billing the procedure code at least 10 times in 2013.

Table 3. Markup Ratios by Hospital for ED and Internal Medicine Procedure Codes Common to Both Specialtiesa.

| Service | Markup Ratio Median (IQR) | |

|---|---|---|

| ED | Internal Medicine | |

| Critical care (n = 1581) | 3.9 (3.2-5.4) | 2.3 (1.9-2.9) |

| Interpretation of ECG (n = 1084) | 6.0 (4.4-7.8) | 3.9 (2.9-5.8) |

| Management and supervision of oxygen chamber therapy (n = 33) | 2.9 (2.2-3.9) | 2.6 (2.1-3.5) |

| Debridement (n = 24) | 3.0 (2.3-4.2) | 2.7 (2.1-4.1) |

| Intubation (n = 79) | 4.6 (3.4-6.0) | 2.9 (2.1-4.2) |

| Insertion of IV (n = 51) | 5.4 (4.1-6.7) | 4.2 (2.9-5.6) |

| Wound care (n = 25) | 4.3 (3.3-6.0) | 4.2 (3.6-5.9) |

| Interpretation of chest radiograph (n = 19) | 4.6 (3.8-5.5) | 4.5 (3.0-4.9) |

Abbreviations: ECG, electrocardiogram; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range.

Ranked by national total Medicare-allowable amounts paid to emergency medicine physicians in 2013. Hospital numbers and national Medicare-allowable amounts are limited to hospitals with at least 1 or more physician billing the procedure code at least 10 times in 2013. Only hospitals with internal medicine and emergency medicine physicians billing for the service were included in this analysis (n = 1986).

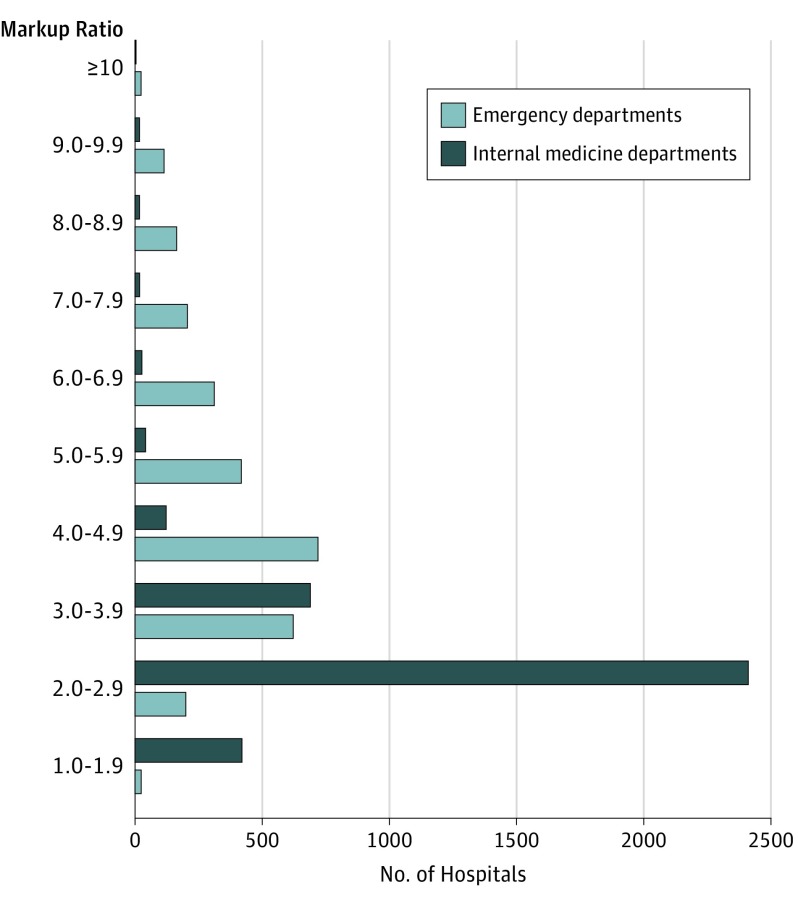

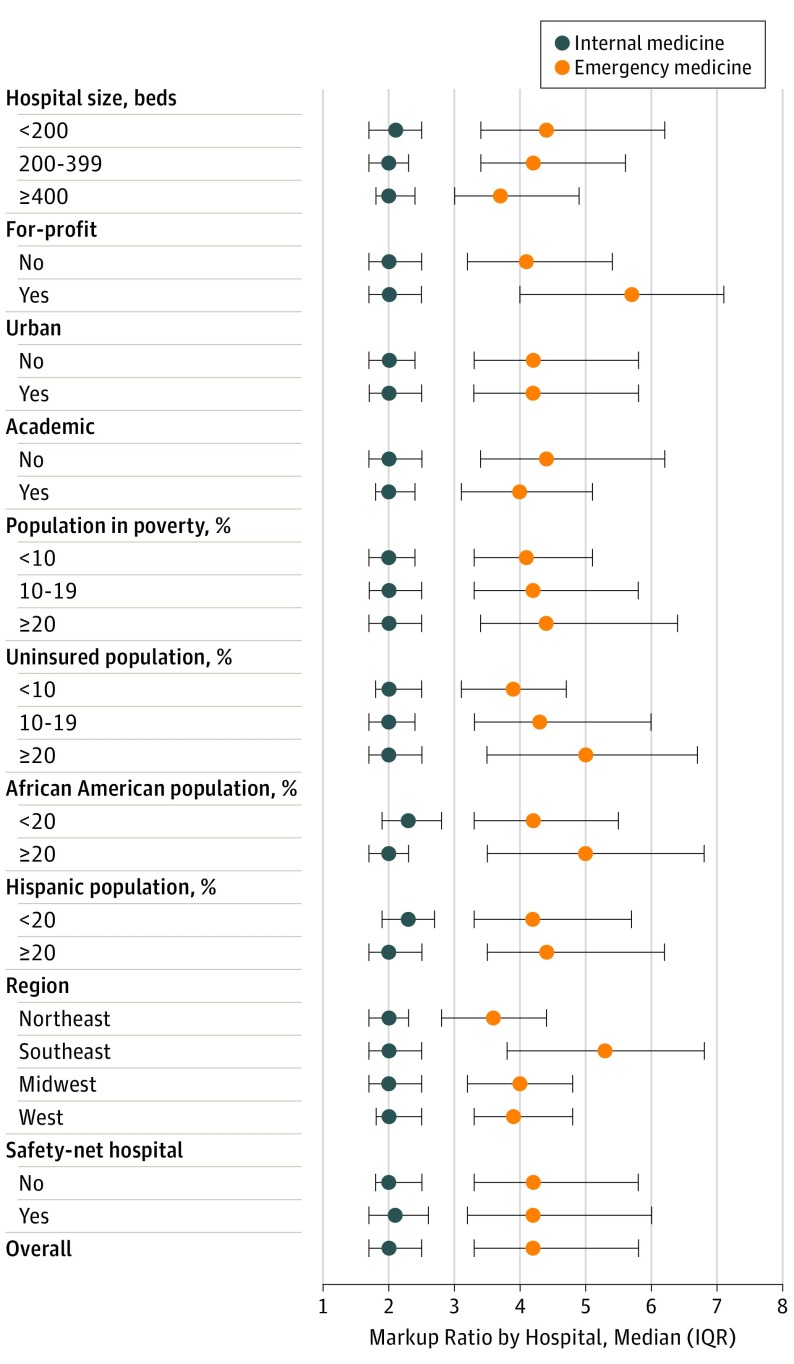

By hospital, the aggregated markup ratio for all ED services ranged from 1.0 to 12.6 (median, 4.2; interquartile range [IQR], 3.3-5.8); the aggregated markup ratio for all internal medicine services ranged from 1.0 to 14.1 (median, 2.0; IQR, 1.7-2.5) (Figure 1). Greater ED markup ratios by hospital (n = 2707) were associated with for-profit status (median, 5.7; IQR, 4.0-7.1), greater uninsured population (median, 5.0; IQR, 3.5-6.7; ≥20% uninsured), African American (median, 5.0; IQR, 3.5-6.8; ≥20% African American) and Hispanic (median, 4.4; IQR, 3.5-6.2; ≥20% Hispanic) patient populations, and location in the southeastern United States (median, 5.3; IQR, 3.8-6.8) (Figure 2 and eTable in the Supplement). These associations between markups and hospital characteristics were not present for internal medicine services.

Figure 1. Variation in Markup Ratios by Hospital in Emergency Departments (n = 2707) and Internal Medicine Departments (n = 3669).

Shown are aggregated markup ratios for all services provided by each department in 2013.

Figure 2. Hospital Characteristics Associated With Higher Markup Ratios in Emergency Departments (n = 2707) and Internal Medicine Departments (n = 3669).

Shown are hospitals’ aggregated markup ratios (median and interquartile range [IQR]) for all services provided in the emergency department (ED) or internal medicine department in 2013. A 1-U increase in the ED markup ratio means that, for every $100 in Medicare-allowable amount billed, the ED charged an additional $100. Multivariable regression coefficients are given in the eTable in the Supplement.

Discussion

In this national study of hospital pricing practices in 2013, we found wide variation in excess charges for ED services relative to what Medicare would have paid. Moreover, ED services were generally priced higher than those in the internal medicine department for the same services within a given hospital. Emergency departments with the greatest markups were more likely to be for-profit and serve larger uninsured populations. These findings reinforce the recent interest among states in protecting patients from excess medical charges.

In considering all ED services, for every $100 in Medicare-allowable amounts, different hospitals charged patients between $100 (markup ratio, 1.0) and $1260 (markup ratio, 12.6), with a median of $420 (markup ratio, 4.2); in contrast, the median hospital’s internal medicine charge would have been $200 (markup ratio, 2.0). The variation in markup on specific ED services was in many instances greater. For physician interpretation of electrocardiograms, which had a median Medicare-allowable amount of $16, different EDs charged between $18 (markup ratio, 1.1) and $317 (markup ratio, 20.0), with a median of $95 (markup ratio, 6.0). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies showing wide variation in ED charges by hospital for similar conditions and levels of visits.

We also found that, within a hospital, common ED services were generally priced higher than the same services in the internal medicine department. For example, the median hospital charged an additional $34 for interpreting an electrocardiogram when performed by an emergency medicine physician ($96; markup ratio, 6.0) relative to an internal medicine physician ($62; markup ratio, 3.9). Our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that hospitals may set chargemaster prices strategically across departments to increase revenues. In our study, for-profit hospitals and hospitals serving larger uninsured populations charged higher amounts in their EDs, but this was not the case for internal medicine services. Markups in the ED may represent cost-shifting to cover expenditures on uncompensated care. At least 7 states, including California, have passed legislation to protect the uninsured against having to pay chargemaster prices. For example, the 2006 Hospital Fair Pricing Act mandated that hospitals limit the charges to the low-income uninsured to Medicare-allowable amounts, resulting in a two-thirds reduction in the collection rate among the uninsured between 2004 and 2012.

In addition to uninsured patients, insured but out-of-network patients can become subject to chargemaster prices. In the course of negotiations between insurers and physicians over payment rates, patients of physicians who remain out of network may receive a balance bill for the difference between the chargemaster price and the amount paid by the insurer. Out-of-network care can also result from hospitals outsourcing ED and other physician services to private contractors who are not part of the hospital’s insurer network. Recent studies suggest that as many as 22% of ED visits at an in-network hospital may include services from an out-of-network physician, creating potential balance bills in each case. Given that patients have little opportunity to comparison shop for ED services, the variation in excess charges across hospitals is especially problematic.

Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) requires health plans to cover out-of-network ED visits with similar percentages of cost sharing to in-network care, there remains no national legislation that addresses the issue of balance bills. However, in at least 15 states, legislation with varying levels of breadth and depth have attempted to protect patients from these “surprise medical bills.” Proposed or passed legislative actions include requiring hospitals and insurers to disclose out-of-network status prior to care, compelling insurance companies to pay the full balance bill, setting a “usual and customary” rate determined by analyses of previous payments or employing state-led mediation, and banning balance billing altogether. New York’s 2015 “Emergency Medical Services and Surprise Bills” law further requires that hospitals negotiate directly with the insurer for all out-of-network payments, thus holding the patient harmless from surprise medical bills. A second feature that distinguishes the New York law is that it protects patients against balance bills in all settings—not just in the ED. Legislation may also be most protective against surprise medical bills from other specialties with high excess charges, including anesthesiology, radiology, neurosurgery, and pathology.

A number of other approaches to protecting patients not yet present in state or national law may also be considered. Price transparency has been suggested as a way for patients to avoid high-charge hospitals by comparison shopping, but this is usually difficult in emergent situations. For now, price transparency may be most useful for “shoppable” elective services, such as colonoscopies. Another proposed approach would cap all charges at 125% of the Medicare-allowable amount to eliminate extreme charge variation. This form of price regulation, however, has the potential to alter the market dynamics of insurance network negotiations if applied to out-of-network patients. A third proposal would require hospitals to sell a bundled ED care package that includes all professional and facility fees and therefore maintain a pool of employees and contracted physicians who agree to accept reasonable payment rates a priori.

Limitations

Our findings should be considered in the context of some important limitations. First, we derived our markup ratios from the physician professional fees, which do not include facility and technical fees also charged by the hospital. Second, data on patients’ insurance type or the amount actually paid by the patients were unavailable. In some cases, uninsured and out-of-network patients may have negotiated with the hospital to pay less than the billed charges. A 2011 survey of 721 privately insured adults found that 14% of patients negotiated their out-of-network bills with hospitals and physicians and were successful about half the time. These findings support the need to increase patient awareness and enact further protections. Third, we identified ED services based on the physician’s specialty as collected by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. In some cases, physicians whose primary specialty is internal medicine may have provided services in the ED. However, internal medicine physicians who performed services in the ED would have caused a regression toward the mean and underestimated the differences between the 2 specialties when ED markups exceeded internal medicine markups. Finally, we used United States Census data to estimate the uninsured and minority populations in each hospital’s zip code, which may not be representative of the patients who presented to the hospital.

Conclusions

Using national Medicare payment data, our study demonstrates the wide variation in the prices EDs charge patients for medical services, which can vary between 1.0 and 12.6 times the Medicare-allowable amount by hospital. Moreover, we found that hospitals typically charge patients more for similar services when performed by an ED physician compared with an internal medicine physician. In this context, the ongoing trends of uninsurance, hospital consolidation, and narrowing insurance networks since implementation of the Affordable Care Act are poised to increase the potential for patient financial harm in the years to come. Now, more than ever, protecting uninsured and out-of-network patients from highly variable hospital pricing should be a policy priority.

eTable. Hospital Characteristics Associated with Higher Markup Ratios

References

- 1.Hsia RY, Akosa Antwi Y. Variation in charges for emergency department visits across California. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(2):120-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bai G, Anderson GF. US hospitals are still using chargemaster markups to maximize revenues. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1658-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyanko KA, Pong DD, Bahan K, Curry LA. Patient experiences with involuntary out-of-network charges. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(5):1704-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai G, Anderson GF. Extreme markup: the fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson GF. From “soak the rich” to “soak the poor”: recent trends in hospital pricing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(3):780-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gani F, Ejaz A, Makary MA, Pawlik TM. Hospital markup and operation outcomes in the United States. Surgery. 2016;160(1):169-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himmelstein DU, Warren E, Thorne D, Woolhandler S. Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;(suppl web exclusives):W5-63-W5-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiel P, Arnold C. From the E.R. to the courtroom: how nonprofit hospitals are seizing patients’ wages. https://www.propublica.org/article/how-nonprofit-hospitals-are-seizing-patients-wages. Published December 10, 2014. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 9.Kiel P, Arnold C. Nonprofit hospital stops suing so many poor patients: will others follow? https://www.propublica.org/article/nonprofit-hospital-stops-suing-so-many-poor-patients-will-others-follow. Published June 1, 2016. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 10.Kyanko KA, Curry LA, Busch SH. Out-of-network physicians: how prevalent are involuntary use and cost transparency? Health Serv Res. 2013;48(3):1154-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Health Policy Forum Forum session: going out of network: why it happens, what it costs, and what can be done. http://www.nhpf.org/library/details.cfm/2952. Published December 6, 2013. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 12.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Physician and other supplier data CY 2013. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Physician-and-Other-Supplier2013.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 13.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Physician Compare national downloadable file. https://data.medicare.gov/Physician-Compare/Physician-Compare-National-Downloadable-File/mj5m-pzi6. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Data brief: evaluation of national distributions of overall hospital quality star ratings. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-21-2.html. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 15.National Association of Public Hospitals and Health Systems What is a safety net hospital? http://literacynet.org/hls/hls_conf_materials/WhatIsASafetyNetHospital.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 16.Bai G, Anderson GF. Variation in the ratio of physician charges to Medicare payments by specialty and region. JAMA. 2017;317(3):315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper Z, Scott Morton F. Out-of-network emergency-physician bills—an unwelcome surprise. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(20):1915-1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldwell N, Srebotnjak T, Wang T, Hsia R. “How much will I get charged for this?” patient charges for top ten diagnoses in the emergency department. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai G. California’s Hospital Fair Pricing Act reduced the prices actually paid by uninsured patients. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):64-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnick G, Fonkych K. Fair pricing law prompts most California hospitals to adopt policies to protect uninsured patients from high charges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1101-1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall MA, Ginsburg PB, Lieberman SM, Adler L, Brandt C, Darling M Solving surprise medical bills. https://www.brookings.edu/research/solving-surprise-medical-bills/. Published October 13, 2016. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 22.Garmon C, Chartock B. One in five inpatient emergency department visits may lead to surprise bills. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(1):177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pollitz K. Surprise medical bills. http://kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/surprise-medical-bills/. Published March 17, 2016. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 24.Robert Woods Johnson Foundation. Hoadley J, Ahn S, Lucia K Balance billing: how are states protecting consumers from 4 unexpected charges? http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2015/06/balance-billing--how-are-states-protecting-consumers-from-unexpe.html. Published June 2015. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 25.New York State Department of Financial Services Protection from surprise bills and emergency services. 2015. http://www.dfs.ny.gov/consumer/hprotection.htm. Updated February 14, 2017. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 26.Sinaiko AD, Rosenthal MB. Examining a health care price transparency tool: who uses it, and how they shop for care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(4):662-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.HealthAffairs Blog. Skinner J, Fisher E, Weinstein J The 125 percent solution: fixing variations in health care prices. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/08/26/the-125-percent-solution-fixing-variations-in-health-care-prices/. Published August 6, 2014. Accessed January 30, 2017.

- 28.Kyanko KA, Busch SH. Patients’ success in negotiating out-of-network bills. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(10):647-652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu T, Wu AW, Makary MA. The potential hazards of hospital consolidation: implications for quality, access, and price. JAMA. 2015;314(13):1337-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melnick GA, Fonkych K. Hospital prices increase in California, especially among hospitals in the largest multi-hospital systems. Inquiry. 2016;53:0046958016651555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. Narrow networks and the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(7):669-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Hospital Characteristics Associated with Higher Markup Ratios