Abstract

This cross-sectional survey study evaluates perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes.

Although a recent study showed that hospital mortality and readmission rates were lower for Medicare patients treated by female than male physicians, women physicians are paid less, are less likely to be promoted, and, on average, spend 8.5 more hours per week on household activities, even after adjusting for age, experience, specialty, clinical revenue, and research productivity. One mechanism may be that in current work environments, childbearing and child rearing may limit opportunities and advancement for women physicians. It is not known, however, how motherhood specifically affects perceived discrimination among women physicians.

Methods

Established in 2014, the Physician Moms Group is an online community with more than 60 000 physician members in the United States who self-identify as mothers (including adoptive or foster mothers). The group is active with an average of 415 new posts, 7413 comments, and 24 829 “likes” daily. On June 17, 2016, we posted an online cross-sectional survey collecting demographic, physical, and reproductive health data and asking about perceived workplace discrimination and desired workplace changes. We assessed self-reported burnout using the Mini Z Burnout Survey. To assess discrimination, we asked “Have you ever experienced discrimination based on the following?” Possible responses were race or ethnicity, gender, age, being an international medical graduate, sexual orientation or gender identity, pregnancy or maternity leave, breastfeeding, mental health problems, and physical disability. Maternal discrimination was defined as self-reported discrimination based on pregnancy, maternity leave, or breastfeeding. Participants were also asked “Have you ever experienced any of the following forms of discrimination at your workplace?” and were asked to identify 3 workplace changes that were most important. The Figure illustrates the distribution of all possible responses.

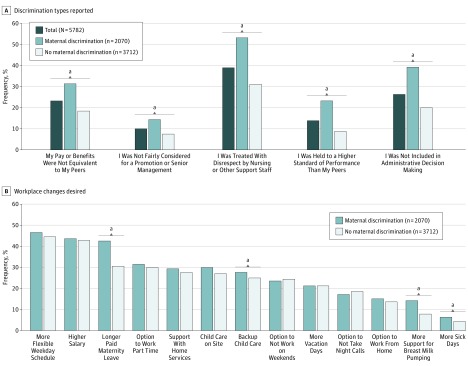

Figure. Survey Responses.

A, Survey question: “Have you ever experienced any of [the illustrated] forms of discrimination at your workplace? (Please select all that apply.)” B, Survey question: “Which of [the illustrated] workplace changes would be most important to you? Please select your top 3.”

aP < .05 for maternal discrimination vs no maternal discrimination by the χ2 test.

When the survey was first posted, 11 887 members viewed it. Two reminder posts on July 18, 2016, and July 30, 2016, had 9082 and 10 074 member views, respectively. Since 82.5% of respondents visit the forum daily, we estimate 16 059 unique views of at least 1 post. A total of 5782 physician mothers completed the survey and provided responses that could be analyzed (participation rate of 16.5% based on 34 956 active users during the period, and 36.0% based on the estimated 16 059 unique views). We used logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusting for age, race/ethnicity, specialty, and practice setting. The University of California, San Francisco institutional review board approved the study.

Results

Of 5782 total respondents, 4507 (77.9%) reported any type of discrimination. Specifically, 3833 (66.3%) reported gender discrimination, and 2070 (35.8%) reported maternal discrimination. Of those reporting maternal discrimination, 1854 (89.6%) reported discrimination based on pregnancy or maternity leave, and 1002 (48.4%) reported discrimination based on breastfeeding. Of the 4222 respondents who reported either gender or maternal discrimination, 1681 (39.8%) reported both; 2152 (51.0%) reported gender discrimination alone; and 389 (9.2%) reported maternal discrimination alone.

The Table summarizes the characteristics of total respondents and specifically those reporting maternal discrimination. Maternal discrimination was associated with higher self-reported burnout (45.9% burnout in those with maternal discrimination vs 33.9% burnout in those without; adjusted odds ratio, 1.74; 95% CI, 1.55-1.95; P < .001).

Table. Characteristics of the Survey Respondents.

| Characteristic | Respondents, No. (%) | OR (CI) for Experiencing Maternal Discriminationb | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 5782) |

Experienced Maternal Discriminationa (n = 2070) |

|||

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤30 | 197 (3.4) | 95 (48.2) | 1.37 (1.01-1.85) | .04 |

| 31-35 | 1696 (29.3) | 684 (40.3) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 36-40 | 2253 (39.0) | 834 (37) | 0.88 (0.77-1.00) | .05 |

| 41-45 | 1053 (18.2) | 314 (29.8) | 0.63 (0.54-0.75) | <.001 |

| ≥46 | 583 (10.1) | 143 (24.5) | 0.47 (0.38-0.59) | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicityc | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4000 (69.2) | 1485 (37.1) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Non-Hispanic black | 211 (3.6) | 64 (30.3) | 0.77 (0.57-1.04) | .09 |

| Asian | 792 (13.7) | 248 (31.3) | 0.77 (0.65-0.91) | .002 |

| Hispanic | 440 (7.6) | 150 (34.1) | 0.91 (0.74-1.12) | .39 |

| Other | 266 (4.6) | 91 (34.2) | 0.87 (0.67-1.14) | .31 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not currently married, never married, or divorced | 315 (5.4) | 94 (29.8) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Married | 5457 (94.4) | 1976 (36.2) | 1.11 (0.86-1.44) | .43 |

| Children, No. | ||||

| 0 | 71 (1.2) | 14 (19.7) | 0.46 (0.25-0.83) | .01 |

| 1 | 1724 (29.8) | 591 (34.3) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 2 | 2663 (46.1) | 929 (34.9) | 1.24 (1.09-1.43) | .002 |

| 3 | 1035 (17.9) | 409 (39.5) | 1.64 (1.38-1.95) | <.001 |

| >3 | 273 (4.7) | 123 (45.1) | 2.30 (1.75-3.03) | <.001 |

| At least 1 child <6 y | ||||

| No | 1273 (22.0) | 318 (25) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 4345 (75.1) | 1702 (39.2) | 1.58 (1.31-1.91) | |

| Currently pregnant or given birth in past year | ||||

| No | 4066 (70.3) | 1381 (34) | 1 [Reference] | .73 |

| Yes | 1672 (28.9) | 677 (40.5) | 1.09 (0.96-1.24) | |

| Trainee, resident, or fellow | ||||

| No | 5244 (90.8) | 1804 (34.4) | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 534 (9.2) | 266 (49.8) | 1.52 (1.23-1.87) | |

| Medical specialty | ||||

| Anesthesia | 187 (3.2) | 88 (47.1) | 1.92 (1.32-2.80) | <.001 |

| Dermatology | 103 (1.8) | 39 (37.9) | 1.32 (0.83-2.11) | .24 |

| Emergency medicine | 516 (8.9) | 214 (41.5) | 1.54 (1.16-2.06) | .003 |

| Family medicine | 950 (16.4) | 335 (35.3) | 1.15 (0.87-1.52) | .32 |

| Internal medicine | 1291 (22.3) | 462 (35.8) | 1.23 (0.95-1.60) | .12 |

| Neurology | 139 (2.4) | 55 (39.6) | 1.36 (0.91-2.03) | .14 |

| Obstetrics-gynecology | 709 (12.3) | 244 (34.4) | 1.22 (0.91-1.65) | .19 |

| Ophthalmology | 96 (1.7) | 42 (43.8) | 1.85 (1.14-3.00) | .01 |

| Pathology | 95 (1.6) | 36 (37.9) | 1.27 (0.78-2.07) | .34 |

| Pediatrics | 1166 (20.2) | 372 (31.9) | 0.98 (0.75-1.27) | .86 |

| Psychiatry | 314 (5.4) | 103 (32.8) | 1.02 (0.72-1.44) | .92 |

| Radiology | 109 (1.9) | 41 (37.6) | 1.43 (0.90-2.29) | .13 |

| Surgery | 278 (4.8) | 117 (42.1) | 1.57 (1.11-2.22) | .01 |

| Other | 61 (1.1) | 18 (29.5) | 0.84 (0.46-1.54) | .58 |

| Practice setting | ||||

| Private practice | 2143 (37.1) | 699 (32.6) | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Academic | 1957 (33.8) | 770 (39.3) | 1.27 (1.11-1.45) | <.001 |

| Public hospital | 444 (7.7) | 145 (32.7) | 0.96 (0.77-1.20) | .71 |

| HMO | 266 (4.6) | 87 (32.7) | 1.05 (0.79-1.38) | .75 |

| VA | 103 (1.8) | 27 (26.2) | 0.75 (0.48-1.19) | .23 |

| Military | 105 (1.8) | 35 (33.3) | 0.95 (0.62-1.45) | .81 |

| Not currently working | 113 (2.0) | 48 (42.5) | 1.71 (1.16-2.53) | .01 |

Abbreviations: HMO, health maintenance organization; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; VA, Veterans Affairs institution.

Missing data were not shown.

Adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, medical specialty, and practice type.

The odds of discrimination of any type were significantly higher among non-Hispanic blacks overall (OR, 4.3; 95% CI, 2.49-7.26 for all types of discrimination; P < .001).

Overall, 38.8% of physicians experienced disrespectful treatment by nursing or other support staff (n = 2246). Among the 2070 who reported maternal discrimination, the most common manifestations were disrespectful treatment by nursing or other support staff (52.9%; n = 1097), not being included in administrative decision making (39.2%; n = 811), and pay and benefits not equivalent to male peers (31.5%; n = 651) (Figure, A).

Workplace changes that the respondents considered most important are illustrated in the Figure, B. As shown there, physicians who reported maternal discrimination were significantly more likely to value workplace changes related to longer paid maternity leave, backup child care, and support for breastfeeding than those who did not report maternal discrimination.

Discussion

In a large cross-sectional survey of physician mothers, we found that perceived discrimination is common, affecting 4 of 5 respondents, including about two-thirds of the respondents who reported discrimination based on gender and more than a third who reported maternal discrimination. The overlap of groups reporting gender and maternal discrimination was less than half, suggesting that they are somewhat different phenomena.

Important limitations of our study include survey design, the low response rate, and possible selection bias, if those who experience discrimination are more likely to participate in a support group.

Despite substantial increases in the number of female physicians—the majority of whom are mothers—our findings suggest that gender-based discrimination remains common in medicine, and that discrimination specifically based on motherhood is an important reason. To promote gender equity and retain high-quality physicians, employers should implement policies that reduce maternal discrimination and support gender equity such as longer paid maternity leave, backup child care, lactation support, and increased schedule flexibility.

References

- 1.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in us medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, Stewart A, Ubel P, Jagsi R. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(5):344-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Physician Moms Group My PMG: join the community. https://mypmg.com/. Accessed March 9, 2017.

- 6.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and wellness in academic general internal medicine: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004-1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]