Abstract

This study examines assesses inappropriate antibiotic prescribing 12 months after stopping a randomized clinical trial of a behavioral intervention intended to reduce the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections.

Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing contributes to antibiotic resistance and leads to adverse events. A cluster-randomized trial of 3 behavioral interventions intended to reduce inappropriate prescribing found that 2 of the 3 interventions were effective. This study examines the persistence of effects 12 months after stopping the interventions.

Methods

We randomized 47 primary care practices in Boston, Massachusetts, and Los Angeles, California, and enrolled 248 clinicians to receive 0, 1, 2, or 3 interventions for 18 months. All clinicians received education on antibiotic prescribing guidelines. Two behavioral interventions were electronic health record (EHR)–based: (1) suggested alternatives presented order sets that offered nonantibiotic treatments when clinicians attempted to prescribe antibiotics for acute respiratory infections (ARIs) and (2) accountable justification prompted clinicians to enter free-text written justifications for prescribing antibiotics for ARIs. The third behavioral intervention, peer comparison, sent monthly emails to clinicians comparing their inappropriate antibiotic prescribing rates for ARIs to clinicians with the lowest rates.

Interventions began between November 1, 2011, and October 1, 2012. Measurements of baseline antibiotic prescribing began 18 months before the start of the intervention and ended 18 months after intervention stopped. The primary outcome was the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among office visits by adult patients for nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, and influenza. In the study, accountable justification and peer comparison significantly reduced inappropriate antibiotic prescribing at the end of the intervention period. As a prespecified secondary objective, data were collected for 12 months postintervention, ending on April 1, 2015. During the postintervention period, 5 clinicians left the study and were excluded from this analysis.

The analysis was a piecewise logistic hierarchical model, with random effects for practices and clinicians and knots demarcating the intervention start and stop dates for each practice. This model measured the persistence of effects of each intervention during the postintervention period compared with practices that did not receive the intervention, adjusting for exposure to other interventions and practice-level and clinician-level effects. We used Stata (StataCorp), version 14.0, and considered 2-tailed P values less than .05 significant, unless otherwise specified. The institutional review board of each participating institution approved the study and waived patient informed consent.

Results

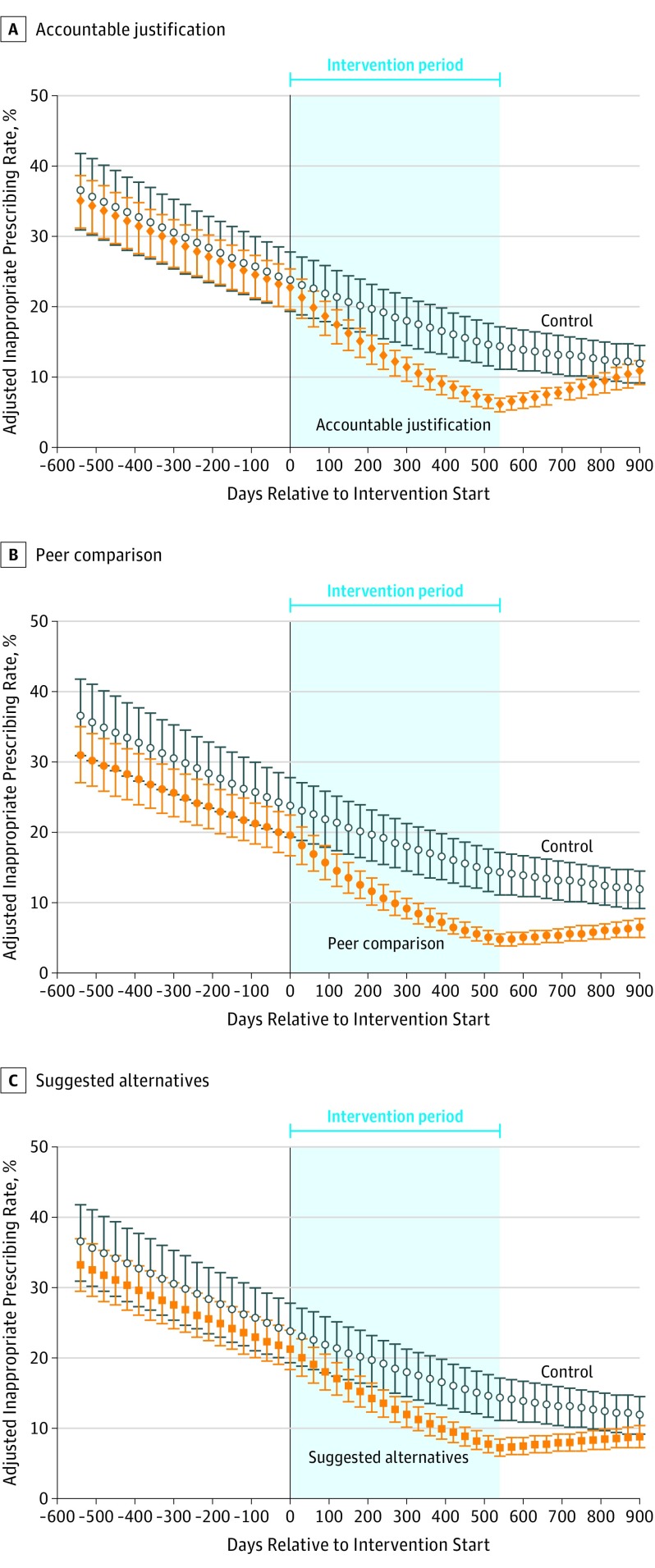

There were 14 753 visits for antibiotic-inappropriate ARIs during the baseline period, 16 959 during the intervention period, and 7489 during the postintervention period. During the postintervention period, the rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing decreased in control clinics from 14.2% to 11.8% (absolute difference, −2.4%); increased from 7.4% to 8.8% (absolute difference, 1.4%) for suggested alternatives (difference-in-differences, 3.8% [95% CI, −10.3% to 17.9%]; P = .55); increased from 6.1% to 10.2% (absolute difference, 4.1%) for accountable justification (difference-in-differences, 6.5 [95% CI, 4.2% to 8.8%]; P < .001); and increased from 4.8% to 6.3% (absolute difference, 1.5%) for peer comparison (difference-in-differences, 3.9% [95% CI, 1.1% to 6.7%]; P < .005) (Figure). During the postintervention period, peer comparison remained lower than control (P < .001; 1-tailed test), whereas accountable justification was not different from control (P = .99; 1-tailed test).

Figure. Adjusted Rates of Antibiotic Prescribing for Antibiotic-Inappropriate Acute Respiratory Tract Infection Visits by Intervention.

Antibiotic prescribing rates at primary care office visits over time for each intervention are marginal predictions from hierarchical regression models of intervention effects, adjusted for concurrent exposure to other interventions and clinician and practice random effects. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Interventions started at day 0 and ended at day 540. The plot in Panel A differs slightly during the intervention period from Panel 2 of the study by Meeker et al due to attrition of 5 clinicians, who were not included in this analysis.

Discussion

In the 12 months after removing behavioral interventions, inappropriate antibiotic prescribing for ARIs increased relative to control practices—whose inappropriate prescribing rates continued to decrease. However, there was still a statistically significant difference between peer comparison and control practices 12 months after the interventions were removed, possibly because this intervention did not rely on EHR prompts whose absence might have been quickly noted by clinicians. Peer comparison might also have led clinicians to make judicious prescribing part of their professional self-image. Although these findings differ from a prior antibiotic-prescribing feedback intervention that did not have persistent effects, peer comparison–induced improvements have been durable in other nonmedical domains.

Limitations of this study are that it only included volunteering clinicians from selected practices, and the postintervention follow-up was only 12 months. Persistence of effects might diminish further as more time passes.

These findings suggest that institutions exploring behavioral interventions to influence clinician decision making should consider applying them long-term.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. . Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persell SD, Friedberg MW, Meeker D, et al. . Use of behavioral economics and social psychology to improve treatment of acute respiratory infections (BEARI). BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeker D, Linder JA, Fox CR, et al. . Effect of behavioral interventions on inappropriate antibiotic prescribing among primary care practices. JAMA. 2016;315(6):562-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG, et al. . Durability of benefits of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention after discontinuation of audit and feedback. JAMA. 2014;312(23):2569-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allcott H, Rogers T. The short-run and long-run effects of behavioral interventions. American Economic Review. 2012;104(10):3003-3037. doi: 10.1257/aer.104.10.3003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]