Abstract

Intracranial saccular aneurysm treatment using endovascular embolization devices are limited by aneurysm recurrence that can lead to aneurysm rupture. A shape memory polymer (SMP) foam-coated coil (FCC) embolization device was designed to increase packing density and improve tissue healing compared to current commercial devices. FCC devices were fabricated and tested using in vitro models to assess feasibility for clinical treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms. FCC devices demonstrated smooth delivery through tortuous pathways similar to control devices as well as greater than 10 min working time for clinical repositioning during deployment. Furthermore, the devices passed pilot verification tests for particulates, chemical leachables, and cytocompatibility. Finally, devices were successfully implanted in an in vitro saccular aneurysm model with large packing density. Though improvements and future studies evaluating device stiffness were identified as a necessity, the FCC device demonstrates effective delivery and packing performance that provides great promise for clinical application of the device in treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms.

Keywords: shape memory polymer, SMP foam, embolization coil, aneurysm

1. Introduction

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH), bleeding into the subarachnoid space in the brain due to intracranial aneurysm rupture, is marked by significant morbidity and mortality rates. Incidence of aSAH occurs in 9.7 – 14.5 out of every 100,000 adults in the United States where at least 25% of patients die and approximately 50% of survivors are left with persistent neurological deficit. [1] Standard endovascular treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms involves the delivery and implantation of embolization coil devices into the aneurysm to promote thrombus formation, tissue healing, and neointimal growth across the aneurysm neck. [2] However, aneurysm recurrence after endovascular coiling occurs in 20.8% of cases, requiring retreatment in 10.3% of cases. [3] Diminished packing density, which is the ratio of implanted device volume to aneurysm volume, as well as poor or unstable thrombus organization have been associated with increased recurrence, among other mechanisms. [4–6] Polymer-embedded coils, including poly(glycolic acid) and hydrogel-coated coils, were introduced to increase packing density or improve thrombus organization but have not resulted in significantly improved long-term clinical outcomes. [7, 8] Therefore, the need still exists for an embolization device capable of increasing packing density and improving thrombus organization.

Shape memory polymer (SMP) foams have been proposed as an advantageous biomaterial for endovascular embolization applications due to their shape recovery capability and interconnected, large surface area porosity. [9–11] Thermo-responsive SMP foams are capable of being programmed to hold a temporary shape until stimulated by heat, at which time they recover their original shape. [12, 13] SMP foams have been reported with increased angiographic occlusion, more advanced healing marked by mature connective tissue, and a thicker neointima layer compared to bare metal coils in porcine saccular aneurysm models. [9, 10] Though both SMP foams and hydrogels exhibit volume-filling capability, SMP foams exhibit interconnected pores with diameters in the hundreds of microns, compared to hydrogel pore sizes less than 10 µm in diameter. [12, 14] This interconnected porosity of the SMP foams acts as a scaffold for blood flow, thrombus formation, and tissue healing throughout the material volume. [9, 10]

A prototype embolization device was previously designed using radially expanding SMP foam over a nickel-titanium (nitinol) and platinum wire backbone and demonstrated to have stable angiographic occlusion and clot formation in a porcine saccular aneurysm model. [11] However, the device exhibited some limitations including restricted working time, which is the time allowed to deliver and reposition the device, and excessive stiffness that increased packing difficulty. To address these limitations, a SMP foam-coated coil (FCC) embolization device was designed utilizing SMP foam over a platinum alloy coil with nitinol core wire. The FCC device is designed to interface with a delivery wire and electrolytic detachment system similar to systems previously used with commercial devices. This study evaluated selected performance and biocompatibility characteristics of the implant device, including ease of delivery and working time through physiologically simulated tortuous flow models and cytocompatibility, to assess feasibility of the device for clinical treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Device Fabrication

The foam-coated coil (FCC) device is composed of shape memory polymer (SMP) foam placed over a platinum-tungsten coil with nickel-titanium (nitinol) core wire. Trimethyl-1,6-hexamethylene diisocyanate, 2,2,4- and 2,4,4-mixture (TMHDI, TCI America Co., Portland, OR), N,N,N′,N′-Tetrakis(2-hydroxypropyl)ethylenediamine (HPED, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), triethanolamine (TEA, 98%, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), and deionized (DI) water (> 17 MΩ cm purity) were used as received to synthesize SMP foam as previously reported by Hasan et al. [15] Helical shaped coil assemblies composed of nickel-titanium wire inserted through the lumen of a platinum-tungsten coil were used as received (Heraeus, Hanau, Germany). For each device, SMP foam was cut into cylinders using a 1 mm diameter biopsy punch, and the coil assembly was threaded through the foam cylinder axis. A single leading coil loop was left uncoated by SMP foam at the distal end. The SMP foam cylinder was saturated with a 4 vol% solution of TMHDI, HPED, and TEA in tetrahydrofuran (THF, anhydrous, EMD Millipore Co., Darmstadt, Germany) and then cured by temperature ramp up to 120 °C at 20 °C/hr and held at 120 °C for 2 hr. The resulting SMP coating adheres the foam to the coil. Under sonication, the devices were cleaned using reverse osmosis (RO) water and isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and then dried at 100 °C for 12 hr under vacuum. SMP foam was heated to approximately 100 °C and radially compressed around the coil using a SC250 stent crimper (Machine Solutions Inc., Flagstaff, AZ) to 0.016 ± 0.001 inches (0.41 ± 0.03 mm) in diameter. FCC devices were fabricated with a helical diameter of 6 mm and straight length of 10 cm (6×10), a helical diameter of 4 mm and straight length of 6 cm (4×6), or a straight length of 20 cm (0×20). The devices were placed into a 0.022 inch (0.56 mm) inner diameter (ID) polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubing for storage and use as an introducer sheath.

For tests using microcatheters, devices were attached to delivery wires. Delivery wires were removed from various sized GDC® embolization coils (Stryker Co., Kalamazoo, MI) and attached to the proximal (clinician side) end of the FCC using 203A-CTH-F UV-cure epoxy (Dymax Co., Torrington, CT). Figure 1 shows a foam-coated coil device before and after radial compression.

Figure 1.

SMP foam-coated coil embolization device. (A) FCC device, 6×10 size, prior to radial compression. (B) FCC device, 6×10 size, after radial compression. (C) FCC device, 6×10 size, after expansion in 37 °C water for 30 min.

2.2. Shape recovery

SMP foam expansion rate was characterized in an aqueous environment. FCC devices, 6×10 size, were straightened and submerged in 37 ± 0.2 °C RO water. Images were taken at 1 min intervals to 10 min total time submerged and at 5 min intervals to 30 min total time submerged. Foam diameter was measured at 5 different locations along each sample length for each time point using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

2.3. Microcatheter tip deflection

Change in microcatheter tip angle during device deployment was measured to assess device stiffness. A 0.022 inch (0.56 mm) ID microcatheter (Stryker Co., Kalamazoo, MI) was steam shaped into a 110° angle with a 1 mm radius of curvature and secured in place. The starting tip angle was measured prior to each sample test from the image using ImageJ software.

Tip deflection was measured for FCC devices, 6×10 size, with delivery wire and GDC-18 2D devices (Stryker Co., Kalamazoo, MI) as controls. Samples were introduced into the microcatheter hub and advanced until the device distal tip was 2 cm proximal to the microcatheter tip. The delivery wire was clamped in an Insight 30 material tester system (MTS) (MTS Systems Co., Eden Prairie, MN) proximal to the microcatheter hub. The MTS advanced the device 0.5 cm through the microcatheter, and an image was taken. This was repeated until 5 cm was deployed out of the microcatheter. The tip angle was measured in each test image using ImageJ software and subtracted from the starting tip angle in order to calculate the tip deflection angle.

2.4. Ease of delivery and working time

Ease of delivery and working time were evaluated on FCC devices through a tortuous path with physiologically simulating flow. Tubing with 2.38 mm ID was secured into a tortuous path with radii of curvature and curve angles based on a model reported by Sugiu et al. and as shown in Figure 2. [16] Deionized (DI) water was heated and pumped through the tubing at average flow rate of 44 ± 2 mL/min. Flow rate was calculated by matching the in vitro system Reynold’s number to in vivo measurements of the middle cerebral artery reported by Reymond et al. [17] Inlet and outlet temperatures were maintained at 37 ± 1 °C. A 0.022 inch (0.56 mm) ID microcatheter was passed through the tortuous path until the microcatheter tip was past the tortuous path and held in 6.35 mm ID tubing. DI water was flushed through the microcatheter at 0.4 mL/min using a syringe pump.

Figure 2.

Tortuous path for ease of delivery and working time testing. The distal tip of the FCC implant is placed at (A) the entry of the tortuous path to start ease of delivery testing. The device is advanced until the junction to the delivery wire reaches (B) to end ease of delivery testing.

Ease of delivery was assessed for FCC devices, 6×10 size, attached to delivery wires with GDC-18 2D devices as controls. Devices were introduced into the microcatheter, and a timer was started. Devices were then advanced until the distal tip of the device was flush with the start of the tortuous path. The delivery wire was secured vertically and clamped 30 cm proximal to the microcatheter hub using a MTS with 50N load cell. Delivery force, the force experienced by the clinician during a procedure, was measured as the device was advanced 29 cm at 14.5 cm/min until the device tip was flush with the microcatheter tip.

Working time was then assessed for FCC devices following ease of delivery testing. The delivery wire was re-clamped in the MTS 6 cm proximal to the microcatheter hub. The delivery force was then measured as the device was deployed 5 cm out and retracted 5 cm at 10 cm/min to simulate repeated device repositioning. The deploy/retract cycle was repeated until an end point was observed: a successful retraction after the total submersion time exceeded 10 min, or mechanical damage was observed during a retraction cycle. A submersion time threshold of 10 min was chosen based on SMP foam shape recovery testing. Once an end point was reached, the total submersion time was recorded as the working time.

2.5. Particle counts during delivery

Particle counts and sizes were characterized from fluid collected during simulated repositioning cycles. DI water was passed through straight tubing with 6.35 mm ID at 44 mL/min and maintained at 37 ± 1 °C. A 0.021 inch (0.53 mm) ID microcatheter was placed into the flow system and flushed with DI water. Fluid flowing through the system was collected in a cleaned glass jar for 5 min to measure the particles in the fluid inherent to the flow system. A FCC device was introduced into the microcatheter until the distal tip was flush with the microcatheter tip and a timer was started. After 5 min total submersion time, the device was deployed 5 cm out and retracted 5 cm at 10 cm/min using the MTS to simulate repeated device repositioning. Fluid was collected in a cleaned glass jar during the simulated repositioning for 5 min. A PC5000 particle counter (Chemtrac, Inc., Norcross, GA) was used to measure 200 mL of each collected fluid for particle counts within diameter ranges of 10–25 µm, 25–50 µm, and 50–100 µm by light obscuration for comparison to the USP <788> standard. [18]

2.6. Chemical extractions

Extracts from FCC devices were evaluated using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Two 0×20 FCC devices were submerged in 10 mL of RO water to meet ISO 10993-12 sample requirements and placed in a heated shaker water bath held at 50 °C for 24 hours with agitation. [19] After extraction, 290 µL of trace element grade nitric acid was added to 10 mL of each RO water solution and analyzed using ICP-MS. The control extracts were similarly prepared to provide a baseline measurement. Concentration of metals in the extracts measured by ICP-MS was reported as µg of metal per gram of device to allow comparison to published permissible limits. This concentration was calculated using Equation 1. The extract metal concentration is divided by two due to two devices being used per extraction volume. The FCC device volume used was the material volume, which uses the foam porosity to calculate the actual material volume of the foam and not the bulk volume.

| (1) |

2.7. Cytocompatibility

A neutral red uptake test was performed on FCC devices to assess cytocompatibility. Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM; VWR, Radnor, PA), penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, 1%; VWR, Radnor, PA), newborn calf serum (NBCS, 10%; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO), and fungizone (0.1%, VWR, Radnor, PA) were used as received to create cell culture media. A 0×20 FCC device was cut to 6 cm length to meet ISO 10993-12 sample requirements and submerged in 2.5 mL of cell culture media held at 37 °C for 72 hours while under agitation. [19]

3T3 fibroblasts (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were seeded in tissue culture plates at a concentration of 5,000 cells per well and placed in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) for 24 hours. An Eclipse TE 2000-S inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc., Tokyo, Japan) was used to observe cell morphology and confirm even cell distribution. Cell culture media was aspirated and cells were incubated with 100%, 50%, 25%, and 10% extract to assess cytocompatibility. Diluted extracts were prepared by adding fresh cell culture media of the appropriate volume. A cytotoxic control (50% IPA), a cytocompatible control (cell culture media that underwent the extraction process with no device), and an untreated control (fresh cell culture media) were included to ensure the validity of the assay. Cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 48 hours.

Extract media was removed, and a neutral red uptake assay (TOX4, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) was added to assess cell viability. Neutral red is actively transported across the cell membrane where it accumulates within lysosomes. Cells were incubated with neutral red for 2.5 hours and then fixed using a solution of 0.1% calcium chloride (CaCl2, Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) in 0.5% formaldehyde (0.5%; Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). The neutral red was solubilized using a solution of 1% acetic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO) in 50% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO). The optical density at 540 nm (OD540) was measured using an Infinite® M200 Pro plate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland) to quantify the remaining neutral red in each well. Cell viability, expressed as a percentage, was calculated using Equation 2, where test is the FCC device extract group, blank is a well with media but no cells, and the control is used as a standard for 100% cell viability.

| (2) |

2.8. In vitro aneurysm model deployment

Coiling stability and packing density were assessed in an in vitro saccular aneurysm model. A saccular aneurysm with a 6.4 mm major diameter, 4.2 mm minor diameter, and 3.9 mm neck diameter on a 3.1 mm diameter parent vessel was designed in SolidWorks software (Dassault Systems, Waltham, MA). The aneurysm and parent vessel model was printed using a Fortus 360mc 3D printer (Stratasys Ltd., Eden Prairie, MN). The model was suspended in acetone vapor to smooth the outer surface and then dried under vacuum. Sylgard 184 polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Dow Corning Corp., Midland, MI) was cast, cured around the model, and the model was dissolved using a heated base bath. The PDMS aneurysm phantom was placed in a flow system, and 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was heated and pumped through the tubing at average flow rate of 66 ± 2 mL/min. Flow rate was calculated by matching the in vitro system Reynold’s number to in vivo measurements of the middle cerebral artery reported by Reymond et al. [17] Inlet and outlet temperature were maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C. A 0.022 inch (0.56 mm) ID microcatheter was positioned with the tip in the aneurysm phantom.

FCC devices, 4×6 size, attached to delivery wires were introduced into the microcatheter and advanced to the aneurysm phantom. A device was deployed into the aneurysm until the detachment zone on the delivery wire was out of the microcatheter. The device was detached by passing a 1.0 mA current through the delivery wire and by placing an uncoated needle in the flow system to electrolytically dissolve the detachment zone on the delivery wire. This was repeated until a subsequent device could not be packed into the aneurysm phantom. Bulk packing density, which assumes the foam is a solid volume, was calculated using Equation 3. Material packing density, which accounts for the porosity of the foam, was calculated using Equation 4. Porosity of SMP foam used in these devices was calculated to be 95% using the method published by Hasan et al. [20]

| (3) |

| (4) |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Shape recovery

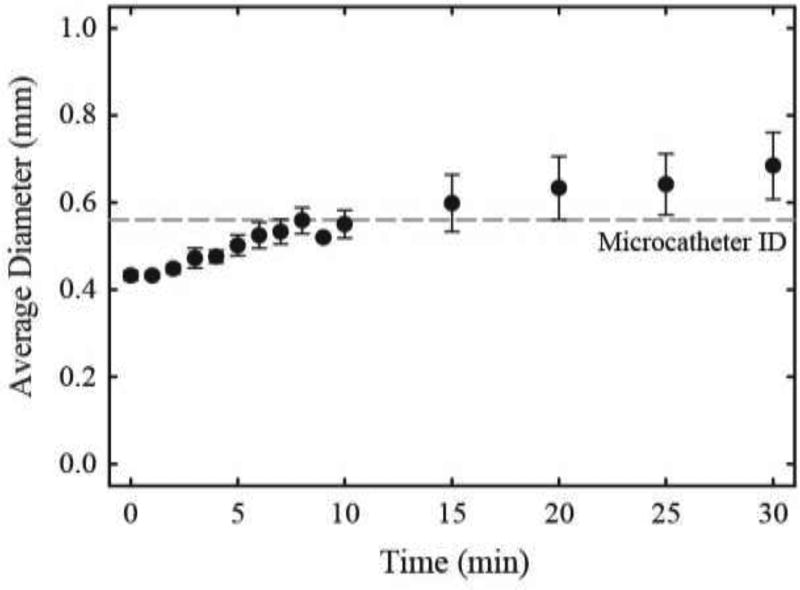

SMP foam expansion of foam-coated coil devices in RO water at 37 °C is shown in Figure 3. Three samples were tested. FCC devices expanded to an average diameter of 0.5 mm at 5 min, 0.56 mm at 10 min, and 0.68 mm at 30 min submersion time. The device expansion is slow in physiological conditions, suggesting an estimated working time of 10 min. This estimated working time was confirmed during working time testing discussed in section 3.3. Furthermore, the expansion at 30 min is approximately equivalent to expanded diameters of hydrogel-coated coils published in 2007, though current commercial hydrogel coated devices exhibit decreased expanded diameter in comparison. [14]

Figure 3.

SMP foam shape recovery. Average diameter and standard deviation of three FCC devices are shown over time submerged in 37 °C RO water. The dashed line represents the inner diameter (ID) of the microcatheter used in subsequent tests.

3.2. Microcatheter tip deflection

Tip deflection angle during device deployment is shown in Figure 4 for FCC and GDC-18 2D control devices. Five FCC samples and three control samples were tested. Average peak deflection angle was 3.976 ± 1.58 ° for FCC devices and −2.92 ± 1.51 ° for control devices. Both FCC and control devices exhibited negative tip deflection during deployment of the leading coil loop. However, as the foam-coated section of the FCC passed through the microcatheter bend, the microcatheter tip angle was increased. This contrasts with the control devices, which exhibited minimal change in deflection angle during deployment of the device. This test indicates that FCC devices exhibit greater stiffness than control devices. However, the absolute peak angle of tip deflection of FCC devices is similar to control devices, and the effect of the observed deflection angles on clinical procedures requires additional study. Future studies should investigate alternative stiffness evaluation methods in order to provide comprehensive assessment of FCC device deployment.

Figure 4.

Microcatheter tip deflection during device deployment. Average angle of deflection and standard deviation are shown for five test (FCC) and three control (GDC-18) devices. Length deployed indicates the length of device deployed out of the microcatheter tip.

3.3. Ease of delivery and working time

Delivery forces during advancement through the tortuous pathway are shown in Figure 5 for FCC and GDC-18 2D control devices. Five FCC samples and three control samples were tested. The average peak force was 0.14 ± 0.01 N for FCC devices and 0.18 ± 0.02 N for control devices. One FCC sample delivery force data was omitted for the initial 2.3 cm of travel distance shown in Figure 5 due to excessive resistance exerted on the delivery wire by the hemostasis valve at the microcatheter hub. The valve was opened to decrease resistance at 2.3 cm travel distance, and the remaining dataset includes the complete FCC sample data. No other samples experienced this test error. FCC devices exhibited similar delivery forces as the control devices throughout the travel distance, indicating that the FCC implant provides no additional resistance to delivery through tortuous pathways compared to current commercial devices.

Figure 5.

Ease of delivery through tortuous pathway. Average delivery force is shown over the travel distance through the tortuous pathway for five test (FCC) devices and three control (GDC-18) devices. Standard deviations are shown every 0.9 cm of travel distance. A moving average over 2 mm travel distance was applied to the delivery force data.

Delivery forces during repositioning cycles are shown in Figure 6. Five FCC devices were tested. Average absolute peak force was 0.62 ± 0.24 N during deployment and 0.42 ± 0.06 N during retraction. All devices exhibited a working time equal to or greater than 10 min whereby all devices could be fully retracted into the microcatheter after 10 min of total submersion time in simulated physiological conditions. However, samples 3 – 5 exhibited delivery wire buckling during deployment. During delivery wire buckling, the FCC implants were not deployed out of the microcatheter and thus were not retracted into the microcatheter during the following cycle. Instead, the buckled delivery wire exerted a negative, or compressive, force on the load cell as indicated by the black arrows in Figure 6. At the start of the subsequent deploy cycle, the delivery wire was guided by hand into the microcatheter to prevent buckling. All devices successfully retracted into the microcatheter during the final test cycle.

Figure 6.

Delivery forces during working time assessment. Delivery force for five FCC devices is shown over the submersion time as samples were deployed out and retracted into the microcatheter. Positive force indicates retraction, and negative force indicates deployment. The black arrows indicate that buckling of the delivery wire proximal to the microcatheter hub had occurred on the previous deploy cycle, causing no implant motion and no subsequent retraction on the indicated cycle. A moving average over 0.5 s submersion time was applied to the delivery force data.

FCC devices provide repositioning with minimal to moderate resistance up to and greater than 10 min following introduction of the device into the microcatheter. This working time is greater than the published repositioning time of 5 min for hydrogel coated coils. [21] Working time is a critical metric for clinical adoption as coils must be able to be easily repositioned inside the aneurysm for effective packing and reduced risk of device migration into the parent vessel. Though all FCC devices in this study exhibited working time equal to or greater than 10 min, future studies should investigate greater time points with greater sample sizes to ensure consistent and reliable repositioning during clinically relevant working times.

3.4. Particle counts during delivery

Particle counts measured during simulated repositioning cycles are shown in Table 1. Average number of particles are shown for particle diameter ranges of 10–25 µm, 25–50 µm, and 50–100 µm for both the flow system with no device as well as during simulated repositioning of the FCC device with the flow system values subtracted out. USP <788>, Particulate Matter in Injections, dictates that solutions greater than 100 mL measured by light obscuration should not exceed 25 particles sized ≥ 10 µm per mL of solution or 3 particles sized ≥ 25 µm per mL of solution. [18] The normalized FCC device values, which are the particles measured during simulated repositioning subtracted by the flow system alone, averaged 75 ± 320 particles sized ≥ 10 µm and 0.4 ± 16 particles sized ≥ 25 µm compared to the flow system. Thus, the FCC devices may be releasing small amounts of particles sized 10–25 µm but are not releasing particles ≥ 25 µm in diameter. Furthermore, the particle counts for the FCC devices measured well below the thresholds of 5000 particles with diameter ≥ 10 µm and 600 particles with diameter ≥ 25 µm when the flow system values were subtracted. This suggests that the FCC devices, even during multiple repositioning cycles and agitation simulating clinical use, exhibit low risk of releasing potentially embolic particles into the bloodstream during use.

Table 1.

Particle counts of the flow system and the FCC device during simulated repositioning cycles. Average number of particles is shown with standard deviation for five samples, where the normalized FCC device value excludes the particle measurement of the flow system alone. USP <788> guidelines provide thresholds of 5000 particles with diameter ≥ 10 µm and 600 particles with diameter ≥ 25 µm. [18]

| Sample | Particle size range | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 10 µm | ≥ 25 µm | |

| Flow system | 562 ± 134 | 16 ± 9 |

| FCC device with system | 637 ± 290 | 17 ± 9 |

| Normalized FCC device | 75 ± 320 | 0.4 ± 16 |

| USP <788> requirement | < 5000 | < 600 |

3.5. Chemical extractions

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) of FCC device extractions in RO water showed no statistical significant difference in metal concentrations between blank extract control samples and the FCC device extracts except for nickel. FCC device extractions resulted in an average of 0.0011 µg/g of nickel per device. Nickel is present in the nitinol wire and may be present in the catalysts used during SMP foam fabrication. The International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) provided guidelines on acceptable elemental impurities, including 6.0 µg/g for nickel. [22] This study suggests that the potentially leached metal content exhibits minimal to no clinical risk, even when considering the potential use of several FCC devices per patient.

3.6. Cytocompatibility

Cell viability of 3T3 fibroblasts exposed to FCC device extracts is shown in Figure 7. Average values are shown for each of 100%, 50%, 25%, and 10% extract concentrations, with six wells per concentration. No morphological changes were observed after cell exposure to device extracts. Average cell viability from device extracts ranged 105–114%. All samples resulting in cell viability greater than 100% show excellent cytocompatibility of FCC devices and provide promise for overall device biocompatibility. Future studies should assess biocompatibility through other standard test methods as cytocompatibility is limited to assessment of extracts and not implanted devices.

Figure 7.

Cytocompatibility of FCC devices by neutral red uptake assay. Cell viability of 3T3 fibroblasts is shown for FCC devices compared to blank (media without cells) and control (standard for 100% viability) groups. Average viability of six wells is shown with standard deviation for each extract concentration.

3.7. In vitro aneurysm model deployment

Device deployment into the in vitro wide-necked aneurysm model is shown in Figure 8. Three FCC devices, 4×6 size, were implanted into the aneurysm model. Packing of the third FCC device was hindered by excessive resistance to buckling. As the aneurysm was packed, less volume was available for coiling to occur, and microcatheter kick-back, i.e. pushing back of the microcatheter tip out of the aneurysm, occurred repeatedly. Although all three devices were successfully positioned into the aneurysm, future studies should investigate buckling force of FCC devices in various sized aneurysm models.

Figure 8.

FCC device deployment into in vitro wide-necked aneurysm model. (A) Aneurysm model prior to device deployment. Air bubbles in the flow system are visible. (B) First FCC device deployment. (C) Second FCC device deployment. (D) Third FCC device deployment. (E) Packed aneurysm model 30 min after implant of the third device. (F) Reverse side of packed aneurysm model 30 min after implant of third device.

Bulk packing density was calculated to be 37% with no foam expansion and 92% with foam expansion. These packing densities are similar to published average values for bare platinum coils (30–31%) and hydrogel-coated coils (76–85%). [23, 24] As increased packing density has been associated with stable long-term occlusion, the large bulk packing densities achieved with expanded FCC devices suggest that stable long-term occlusion in vivo can be achieved. [4, 5] However, though FCC device bulk packing density is very similar to current commercial devices, the actual implanted material volume is much less due to the SMP foam porosity. Material packing density was calculated to be 11% for FCC devices in the in vitro aneurysm model. This large bulk packing density with small material packing density is potentially advantageous as the FCC device provides scaffolding throughout the majority of the aneurysm space while allowing the majority of the volume to be filled by stable thrombus formation and healed tissue. This may improve upon previous devices as bare platinum coils provide less bulk occlusion, and hydrogel-coated coils displace blood instead of providing porous scaffolding throughout the aneurysm volume. In vivo studies should be conducted to investigate the effect of high porosity occlusion from FCC devices on aneurysm treatment.

4. Conclusions

A shape memory polymer (SMP) foam-coated coil (FCC) embolization device was designed and demonstrates effective delivery and packing performance for treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms. The FCC device provides clinician-familiar deliverability and use combined with excellent packing volume and scaffolding capability of porous shape memory polymer foam. In addition, low physical particle counts, minimal chemical extractables, and excellent cytocompatibility are promising early results in showing biocompatibility and reduced risk of use of the FCC device. Further tests will be necessary to investigate improvements to device stiffness as well as continued assessment of biocompatibility. Overall, this work demonstrates excellent promise for clinical realization of the SMP foam-coated coil embolization device for treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms.

Highlights.

Design of an implantable medical device utilizing shape memory polymer foam

Benchtop demonstration of device performance for treatment of intracranial saccular aneurysms

Preliminary analysis of device biocompatibility by pilot verification studies

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marziya Hasan for her technical assistance in this work. Use of the TAMU/LBMS and Mr. Bo Wang and Dr. Yohannes Rezenom are acknowledged. This work was supported by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant U01-NS089692.

Abbreviations

- aSAH

aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage

- FCC

foam-coated coil

- SMP

shape memory polymer

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

Shape Memory Medical, Inc. (SMM) owns the commercial license for clinical vascular embolization application of the technology shown in this work. The authors disclose that Duncan Maitland is a founder, board member, and shareholder of SMM. Anthony J Boyle, Mark A Wierzbicki, and Wonjun Hwang are or were employed by SMM at the time of this work. In addition, Andrew C Weems holds stock options with SMM.

References

- 1.Connolly ES, Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, Derdeyn CP, Dion J, Higashida RT, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:1711–37. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brinjikji W, Kallmes DF, Kadirvel R. Mechanisms of Healing in Coiled Intracranial Aneurysms: A Review of the Literature. Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:1216–22. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferns SP, Sprengers MES, van Rooij WJ, Rinkel GJE, van Rijn JC, Bipat S, et al. Coiling of Intracranial Aneurysms: A Systematic Review on Initial Occlusion and Reopening and Retreatment Rates. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2009;40:e523–e9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.553099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knap D, Gruszczyńska K, Partyka R, Ptak D, Korzekwa M, Zbroszczyk M, et al. Results of endovascular treatment of aneurysms depending on their size, volume and coil packing density. Neurologia i Neurochirurgia Polska. 2013;47:467–75. doi: 10.5114/ninp.2013.38226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leng B, Zheng Y, Ren J, Xu Q, Tian Y, Xu F. Endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms with detachable coils: correlation between aneurysm volume, packing, and angiographic recurrence. J Neurointerv Surg. 2014;6:595–9. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2013-010920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ichiro Yuki, Lee Daniel, Murayama Yuichi, Chiang Alexander, Vinters Harry V, Nishimura Ichiro, et al. Thrombus organization and healing in an experimental aneurysm model. Part II. The effect of various types of bioactive bioabsorbable polymeric coils. Journal of neurosurgery. 2007;107:109–20. doi: 10.3171/JNS-07/07/0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White PM, Lewis SC, Gholkar A, Sellar RJ, Nahser H, Cognard C, et al. Hydrogel-coated coils versus bare platinum coils for the endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms (HELPS): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1655–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60408-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Molyneux AJ, Clarke A, Sneade M, Mehta Z, Coley S, Roy D, et al. Cerecyte Coil Trial: Angiographic Outcomes of a Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Endovascular Coiling of Cerebral Aneurysms With Either Cerecyte or Bare Platinum Coils. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:2544–50. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.657254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez JN, Clubb FJ, Wilson TS, Miller MW, Fossum TW, Hartman J, et al. In vivo response to an implanted shape memory polyurethane foam in a porcine aneurysm model. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2014;102:1231–42. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn J, Hwang W, Jessen SL, Keller BK, Miller MW, Tuzun E, et al. Comparison of shape memory polymer foam versus bare metal coil treatments in an in vivo porcine sidewall aneurysm model. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33725. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle AJ, Landsman TL, Wierzbicki MA, Nash LD, Hwang W, Miller MW, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a shape memory polymer foam-over-wire embolization device delivered in saccular aneurysm models. J Biomed Mater Res Part B. 2015 doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singhal P, Rodriguez JN, Small W, Eagleston S, Van de Water J, Maitland DJ, et al. Ultra low density and highly crosslinked biocompatible shape memory polyurethane foams. J Poly Sci B Poly Phys. 2012;50:724–37. doi: 10.1002/polb.23056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson TS, Bearinger JP, Herberg JL, Marion JE, Wright WJ, Evans CL, et al. Shape memory polymers based on uniform aliphatic urethane networks. J Appl Polym Sci. 2007;106:540–51. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cruise GM, Shum JC, Plenk H. Hydrogel-coated and platinum coils for intracranial aneurysm embolization compared in three experimental models using computerized angiographic and histologic morphometry. J Mater Chem. 2007;17:3965–73. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasan SM, Raymond JE, Wilson TS, Keller BK, Maitland DJ. Effects of Isophorone Diisocyanate on the Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Shape-Memory Polyurethane Foams. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2014;215:2420–9. doi: 10.1002/macp.201400407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugiu K, Martin J-B, Jean B, Gailloud P, Mandai S, Rufenacht DA. Artificial Cerebral Aneurysm Model for Medical Testing, Training, and Research. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2003;43:69–73. doi: 10.2176/nmc.43.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reymond P, Merenda F, Perren F, Rüfenacht D, Stergiopulos N. Validation of a one-dimensional model of the systemic arterial tree. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2009;297:H208–H22. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00037.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.<788=Particulate matter in injections. The United States Pharmacopeia—National Formulary, USP. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 19.ISO 10993-12: Biological evaluation of medical devices -- Part 12: Sample preparation and reference materials. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasan SM, Harmon G, Zhou F, Raymond JE, Gustafson TP, Wilson TS, et al. Tungsten-loaded SMP foam nanocomposites with inherent radiopacity and tunable thermo-mechanical properties. Polymers for Advanced Technologies. 2016;27:195–203. doi: 10.1002/pat.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cloft HJ, Kallmes DF. Aneurysm packing with HydroCoil embolic system versus platinum coils: initial clinical experience. Amer J Neurorad. 2004;25:60–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guideline for Elemental Impurities Q3D; International Conference on Harmonisation; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ding YH, Dai DY, Lewis DA, Cloft HJ, Kallmes DF. Angiographic and histologic analysis of experimental aneurysms embolized with platinum coils, matrix, and HydroCoil. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1757–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gaba RC, Ansari SA, Roy SS, Marden FA, Viana MA, Malisch TW. Embolization of intracranial aneurysms with hydrogel-coated coils versus inert platinum coils: effects on packing density, coil length and quantity, procedure performance, cost, length of hospital stay, and durability of therapy. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2006;37:1443–50. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221314.55144.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]