Abstract

Several states have passed Medicaid home and community-based services waivers that expand eligibility criteria and available services for children with autism spectrum disorder. Although previous research has shown considerable variation in these waivers, little is known about the programs’ impact on parents’ workforce participation. We used nationally representative survey data combined with detailed information on state Medicaid waiver programs to determine the effects of waivers on whether parents of children with autism spectrum disorder had to stop working because of the child’s condition. Increases in the Medicaid home and community-based services waiver cost limit and enrollment limit significantly reduced the likelihood that a parent had to stop working, although the results varied considerably by household income level. These findings suggest that the Medicaid waivers are effective policies to address the care-related needs of children with autism spectrum disorder.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a multifaceted, lifelong developmental disorder reported to affect one in sixty-eight children in the United States.1,2 The disorder is characterized by repetitive behaviors, restricted interests, and delays in social interaction and communication.3 ASD occurs across all socioeconomic levels, races, and cultures, with symptoms usually appearing in infancy or toddlerhood. The earlier ASD is diagnosed and evidence-based treatment begins, the better the chance that children will experience enhanced cognitive and adaptive functioning.4–11

Families of children with ASD often have greater challenges accessing services than families of children with many other special health care needs.12–14 Problems obtaining child care for children with ASD can affect parents’ working decisions,15 as can experiencing discontinuities of the professional services and supports for these children.16 Parent and family participation is an important and beneficial component in many ASD treatments,17,18 but the participation and other care coordination demands placed on families mean that at least one parent must reduce his or her hours worked or stop working altogether,12,19–21 which makes it even more difficult for families to pay for the services needed for their children with ASD.

Many states have turned to Medicaid to help finance ASD services, using Medicaid home and community-based services (HCBS) waivers under section 1915(c) of the Social Security Act, both to expand eligibility for Medicaid-reimbursed services and to provide services not covered by their Medicaid plans. With waivers, states have the flexibility to define populations by age, medical condition, and geographic location; limit the number of people who receive waiver services at any one time; disregard income and resource rules that are used to determine Medicaid eligibility; and add services not already included in their state plans.22 Fifty current or former HCBS waivers in twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia include children with ASD in their target populations. Although previous studies have documented the considerable variation both within and between states in waiver characteristics23 and have shown that waiver characteristics reduce unmet needs among children with ASD,24 no studies have assessed waivers’ impact on parents’ workforce participation.

In this article we use data from a nationally representative survey to explore the extent to which having a waiver, and the waiver’s particular characteristics, are associated with parents’ ability to stay in the workforce and still meet the needs of their children with ASD.

Study Data And Methods

DATA

Data from two consecutive waves (2005–06 and 2009–10) of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs (NS-CSHCN) were used to determine whether or not a parent had to stop working because of the child’s health condition. This is a nationally representative cross-sectional, random-digit-dialed telephone survey that collects information about the physical and emotional health of US children ages seventeen and younger.25,26 Children were categorized as having ASD if their caregiver answered “yes” to the question, “Has a doctor or health professional ever told you that [child’s name] has any of the following conditions…autism, Asperger’s disorder, pervasive development disorder, or other autism spectrum disorder?” To increase the specificity of this question, we limited the sample to children with ASD ages two and older, for whom diagnostic accuracy is greater. Because there may be other factors affecting parental labor-market decisions more broadly, we wanted to include a comparison group from the population of children included in the NS-CSHCN so that we could be more certain that the effects we observed were due to the waiver policies. We chose children with asthma, since asthma is a well-understood physical health condition that has been heavily studied in health services and clinical research and is largely unrelated to ASD.

We used the following question from the NS-CSHCN to determine whether a parent had to stop working because of the child’s condition: “During the past 12 months, has a family member stopped working because of the child’s condition?” Answers from both survey years were combined in the analysis.

Data describing state Medicaid HCBS waiver programs were collected from source materials submitted in support of waiver applications that explicitly targeted children with ASD between 2000 and 2014. Our data collection process is described in more detail elsewhere.23 The following measures characterizing waiver features were constructed: estimated cost, which each state calculates for its own waiver and is defined as the total annual estimated costs to the state of waiver services per individual expected to participate; cost limit, which is defined as the maximum cost to the state of waiver services that each state allowed for individuals enrolled under the waiver; and enrollment limit, which is defined as the maximum number of participants the waiver will serve, expressed as a proportion of the total number of children in the state. Estimated cost is a proxy for the breadth and depth of benefit coverage under the waiver, while cost limit is the expenditure limit for any one participant in the waiver. Higher values for both imply more generous coverage under the waiver.

Thirty-five states were included in the study sample. Between 2005 and 2010, nine states had a section 1915(c) waiver that targeted children with ASD, and twenty-five control states and the District of Columbia did not have a child-specific waiver. We excluded the remaining sixteen states because they had waivers during the study period that included both children and adults, and it was impossible to determine the level of services available for just children under such waivers. States that passed a child-specific waiver between 2005 and 2010, such as Montana (2008), were included among the control states prior to their waiver enactment and as waiver states after enactment.

ANALYSIS

We estimated standard multivariable logistic regression models in which the unit of analysis was the child. Combining across the two waves of the NS-CSHCN, our sample consisted of a total of 17,693 observations of children ages 2–17 with ASD (n = 2,647) or with asthma (n = 15,521) (475 children had both conditions). We normalized the waiver policy measures that were continuous (estimated cost, cost limit, and enrollment limit) across states so that each had a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 among states with active waivers. This allowed us to interpret estimated odds ratios as the effect of a 1-standard-deviation change in the measure, based on the observed variation in policies across states. Other independent variables included in the model were child characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, and insurance status), household characteristics (income, number of adults in household, and whether English was the primary language spoken), and state fixed effects. We specified the multivariable logistic regression models as quasi-difference-in-difference-in-differences models. The triple-difference in our study arises from changes in waiver policies over time (the first difference), across states with and without waivers (the second difference), and for children with ASD relative to children with asthma (the third difference). Ours is a quasi-difference-in-difference-in-differences design because in addition to dichotomous indicators for the waivers, characteristics of the waivers (such as estimated costs and cost and enrollment limits) are continuous measures.

Stata software, version 12.1, was used to conduct all of the data management and analyses. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine.

LIMITATIONS

The study had several limitations. First, we limited our analysis to HCBS waivers that targeted children only; states in which there was also a waiver targeting adults were excluded for those years in which the waiver was active. Although our rationale for this was noted above, it potentially limits the generalizability of our results to states with waivers targeting children only. Second, the NS-CSHCN data were available for the years 2005 and 2010 only, so we were not able to examine the effects of waivers passed before 2005 or after 2010. Third, the diagnosis of ASD relied on parents’ self-reporting and was not validated in these survey data, and there is the potential for both false positives and false negatives. False negatives likely did not influence the results, given the large sample of children without ASD. False positives may have affected the results, although parental report of current ASD status has generally been found to yield few false positives.27 Fourth, parental respondents in the NS-CSHCN with a child with ASD might not have accessed services that were available under the HCBS waiver. Hence, we could not directly observe whether enrollment in the waiver directly affected labor-market participation; we could only observe the relationship between the existence of a waiver (and waiver characteristics) and parental report of stopping work among all parents of children with ASD. Fifth, we had no information on the severity of illness, underlying level of need, or services received.

In addition, we used children with asthma as the comparison group. As we noted above, the NS-CSHCN only includes children with special health care needs, and we thought that it was important to choose a specific condition as the comparator so that we could more easily interpret our findings. We repeated the analyses using children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and children with learning difficulties as the comparator, and the results were substantially unchanged.

Finally, one must always use caution when drawing causal inferences from retrospective data analyses. However, the quasi-difference-in-difference-in-differences design is a particularly strong research design and allowed us to identify changes in rates of parents of children with ASD stopping work before and after policy changes within a state and compare them to changes among parents of children with asthma over the same period. It also allowed us to compare labor-market behavior among parents of children with ASD in states with policy changes to that among similar parents in states without policy changes, which permitted us to control for secular changes in the care of children with ASD. Still, correlation between unobserved factors associated with both the changes in the policy variables within states and labor-market behavior among parents of children with ASD (such as any state or local programs that improved access to ASD services that became effective at the same time as the state HCBS waiver policy) might exist and limit causal interpretation.

Study Results

The number of states with a 1915(c) waiver targeting children with autism spectrum disorder increased from three states (Maryland, Michigan, and Wisconsin) in 2005 to nine states in 2010 (Exhibit 1). The mean estimated cost of services across all waivers increased from $17,732 in 2005 to $26,108 in 2010. The mean waiver cost limit decreased over the same period, from $145,568 in 2005 to $111,569 in 2010, and the mean enrollment limit fell from 1,594 in 2005 to 854 in 2010. There was much variation in these waiver characteristics across states.

EXHIBIT 1.

Summary of Medicaid home and community-based services waivers targeting children with autism spectrum disorder

| Year | 2005 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Number of states | 3 | 9 |

| States includeda | MD, MI, WI | CO, IL, MA, MD, MI, MT, ND, SC, WI |

| Estimated cost, mean (SD) | $17,732 ($6,318) | $26,108 ($11,823) |

| Cost limit, mean (SD) | $145,568 ($64,341) | $111,569 ($97,578) |

| Enrollment limit (SD) | 1,594 (1,649) | 854 (1,515) |

SOURCE Information on state waiver policies was gathered during a systematic review by the authors of waiver applications, renewals, and amendments collected from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and directly from the states. NOTES Only states with at least one active 1915(c) home and community-based services waiver targeting children with autism spectrum disorder during the year with known waiver policy information were included. Estimated cost, cost limit, and enrollment limit are defined in the text. SD is standard deviation.

Sample also includes twenty-five control states, plus the District of Columbia, that did not have a waiver targeting children with autism spectrum disorder during the period of study. The states were AL, AZ, CT, GA, HI, ID, IA, KY, ME, MN, MO, NC, NE, NV, OK, OR, PA, RI, SD, TN, TX, VT, WA, WV, and WY.

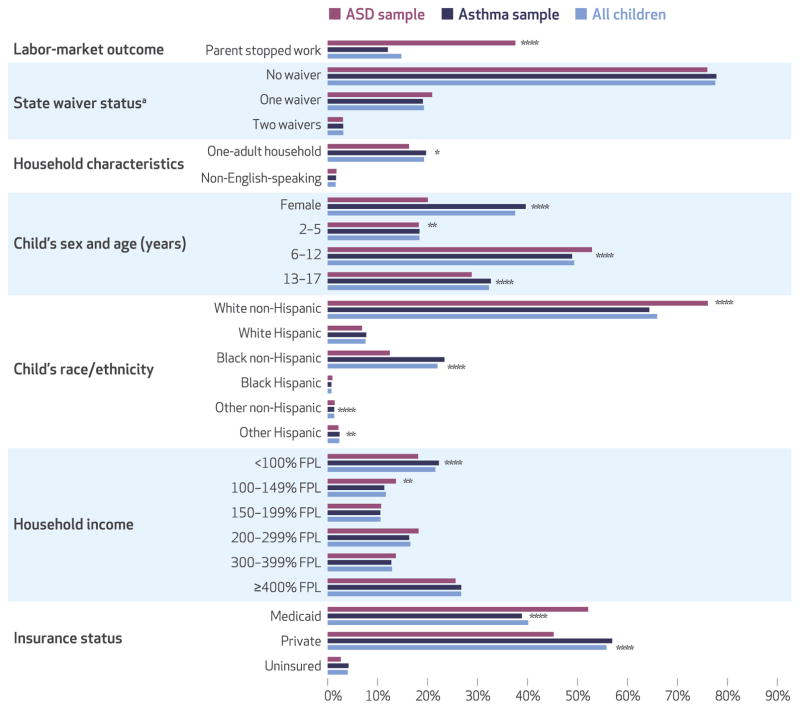

Children with ASD differed from children with asthma on a variety of characteristics (Exhibit 2). Parents of children with ASD were much more likely to have stopped working than parents of children with asthma (37.6 percent versus 12.1 percent, p < 0:001). Children with ASD were more likely than children with asthma to be ages 6–12 (52.9 percent versus 48.9 percent, p < 0:001) and to be insured by Medicaid (52.1 percent versus 38.9 percent, p < 0:001), whereas they were less likely to be from a household with income less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level (18.1 percent versus 22.3 percent, p = 0:001), to be female (20.1 percent versus 39.6 percent, p < 0:001), to be ages 2–5 (18.2 percent versus 18.4 percent, p = 0:038), or to be ages 13–17 (28.8 percent versus 32.7 percent, p < 0:001). We also found significant differences in the distribution of race/ethnicity between the groups. There were no differences in family characteristics or proportion living in a state with a 1915(c) waiver.

EXHIBIT 2. Characteristics of the sample of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or asthma.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2005–06 and 2009–10. NOTE FPL is federal poverty level. aWhether child lives in state with no waiver, one waiver, or two waivers. *p < 0.10 **p < 0.05 ****p < 0.001

In multivariate quasi-difference-in-difference-in-differences logistic regression models examining factors associated with a parent stopping work (Exhibit 3), we found that waiver characteristics were strongly associated with the likelihood of stopping work, but the effects varied considerably by household income. In the regression model using the entire sample (N = 17,693), we found that a 1-standard-deviation increase in the cost limit (the maximum dollar amount that could be spent per child) was associated with decreased odds of a parent of a child with ASD stopping work (odds ratio: 0.83; 95% confidence interval: 0.71, 0.96) compared to a parent of a child with asthma. When we stratified the analysis by household income, we found that the effect of increasing the cost limit was limited to households with incomes less than 200 percent of poverty (n = 6,335; OR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.38, 0.86) and was not statistically significant in households with incomes at or above 200 percent of poverty (n = 11,358). In addition, a 1-standard-deviation increase in the enrollment limit decreased the odds of a parent of a child with ASD stopping work compared with a parent of a child with asthma in households with incomes at or above 200 percent of poverty (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.62, 0.89), but not in households with incomes below 200 percent of poverty. Several other control variables were significantly associated with the likelihood of a parent stopping work because of a child’s health condition, such as the child’s age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status (Exhibit 3).

EXHIBIT 3.

Factors associated with a parent of a child with autism spectrum disorder stopping work, compared to a parent of a child with asthma

| Independent variables | Odds ratio, all households (N = 71,693) | Odds ratio, by household income | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| <200% of poverty (n = 6,335) | ≥200% of poverty (n = 11,358) | ||

| DIFFERENCE-IN-DIFFERENCES POLICY EFFECTSa | |||

|

| |||

| ASD estimated cost | 0.90 | 1.07 | 1.01 |

| ASD cost limit | 0.83** | 0.57*** | 1.29* |

| ASD enrollment limit | 0.93 | 1.06 | 0.74*** |

| ASD no waiver | 0.92 | 1.13 | 0.59**** |

|

| |||

| STATE WAIVER CHARACTERISTICS, MAIN EFFECTS | |||

|

| |||

| Estimated cost | 0.83**** | 0.78*** | 0.85* |

| Cost limit | 1.15**** | 1.40**** | 0.72**** |

| Enrollment limit | 1.22** | 1.38 | 0.89 |

| No waiver | 0.58**** | 0.36**** | 1.47 |

|

| |||

| FAMILY CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

| |||

| One-adult household | 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.56**** |

| Non-English speaking | 1.31 | 1.23 | 1.83 |

| Household income (percent of poverty) | |||

| <100% | 1.57*** | 1.52*** | —b |

| 100–149% | 1.51*** | 1.49*** | —b |

| 150–199% | 1.09 | 1.00 | —b |

| 200–299% | 1.11 | —b | 1.10 |

| 300–399% | 1.09 | —b | 1.10 |

| 400% or more | 1.00 | —b | 1.00 |

|

| |||

| CHILD CHARACTERISTICS | |||

|

| |||

| Has autism spectrum disorder | 5.08**** | 4.03**** | 7.63**** |

| Female | 0.84** | 0.81* | 0.84 |

| Child’s age (years) | |||

| 2–5 | 1.69**** | 1.87**** | 1.42*** |

| 6–12 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 1.04 |

| 13–17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Child’s race/ethnicity | |||

| White Hispanic | 1.42* | 1.68** | 1.16 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.83* | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| Black Hispanic | 0.90 | 1.30 | 0.22** |

| Other non-Hispanic | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| Other Hispanic | 2.07**** | 2.63**** | 0.76 |

| White non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Insurance status | |||

| Medicaid | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Private | 0.40**** | 0.49*** | 0.29**** |

| Uninsured | 1.18 | 1.58 | 0.48* |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis. NOTES The exhibit presents multivariable weighted logistic regression results that show the effects of policy and child and family characteristics on the likelihood that a parent of a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) stopped working relative to a parent of a child with asthma, using a quasi-difference-in-difference-in-differences approach. See the text for more information. Estimated cost, cost limit, and enrollment limit are defined in the text.

These results indicate the effects of a 1-standard-deviation increase in the corresponding waiver characteristic on the likelihood that a parent of a child with ASD stopped working relative to a parent of a child with asthma. “ASD no waiver” is the effect of not having a waiver (versus having a waiver) on the likelihood that a parent of a child with ASD stopped working.

Not applicable.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Discussion

This study examined the effects of Medicaid home and community-based services waivers on the labor-market participation of families with children with autism spectrum disorder. Consistent with previous studies,12,19–21 we found that parents of children with ASD were significantly more likely to stop working because of their child’s condition than parents of children without ASD. However, we found that Medicaid HCBS waivers can alleviate this burden and that characteristics of the waivers are important. Increases in the cost limit and estimated cost significantly reduced the odds of parents of a child with ASD stopping work, relative to parents of a child with asthma.

We found that the effects of 1915(c) waivers varied by household income. For example, increasing the enrollment limit significantly reduced the odds of a parent of a child with ASD stopping work but only in higher-income households. Since these households would most likely not otherwise qualify for Medicaid services, it is perhaps not surprising that waiver enrollment limits would be most effective. Among lower-income households, for which financing ASD care might be most difficult, cost limits—which are a measure of the generosity of services provided under the waiver—were most effective.

Our finding that waiver characteristics affected parental employment even in higher-income households likely reflects the lack of adequate private health insurance coverage for ASD services during the study period.28 Although twenty-two states passed a mandate between 2007 and 2010 requiring private insurers to cover ASD services,29 the limited research suggests that these mandates have not been effective in improving access to care for children with ASD.30

Policy Implications

With health care reform and other policy changes, the health care system for children with autism spectrum disorder is evolving. In July 2014 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued an informational bulletin indicating that behavioral treatment for ASD should be considered covered by state Medicaid plans under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) services benefit.31 Under the original Medicaid statute, this benefit entitles all children to these services. Hence, 1915(c) waivers are not needed to provide services that are already covered under EPSDT to low-income children with ASD. However, the policy landscape related to Medicaid coverage of ASD services remains uncertain and is changing rapidly, as states still have tremendous flexibility about what services to cover for children with ASD. For example, in addition to the behavioral treatments mentioned in the CMS bulletin,31 some states also offer other services (such as respite) and cover more creative treatment models and places of service, while others do not. For example, Maryland’s waiver is administered though the Maryland Department of Education, which enables better coordination of educational and Medicaid services and offers respite, personal care, and caregiver support and training.23 By examining specific waiver characteristics, this study provides critical information for Medicaid policy makers as they consider how to design programs, whether as 1915(c) waivers or as part of the state plan benefit, to provide the best care for children with ASD.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates that waiver characteristics are significantly associated with reduced risk that parents of children with autism spectrum disorder will stop working and that these effects vary considerably by household income. As the policy landscape related to ASD services continues to evolve, families of children with ASD are still likely to face significant challenges in accessing needed services. The results of this study will be important to policy makers as they consider different tools to help meet the needs of this vulnerable population.

Footnotes

This research was previously presented at the Sixth Biennial Conference of the American Society of Health Economists, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 12–15, 2016, and at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting and Expo, in Denver, Colorado, October 29–November 2, 2016.

Contributor Information

Douglas L. Leslie, Professor at the Penn State College of Medicine, in Hershey

Khaled Iskandarani, Research data analyst at the Penn State College of Medicine.

Diana L. Velott, Senior instructor at the Penn State College of Medicine

Bradley D. Stein, Senior behavioral and policy sciences researcher at the RAND Corporation in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

David S. Mandell, Director of the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia

Edeanya Agbese, Project manager at the Penn State College of Medicine.

Andrew W. Dick, Senior economist at the RAND Corporation in Boston, Massachusetts

NOTES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring (ADDM) Network [Internet] Atlanta (GA): CDC; [cited 2016 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/autism/addm.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, Bilder D, Charles J, Constantino JN, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1–23. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6503a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Arlington: APA; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen H, Amerine-Dickens M, Smith T. Early intensive behavioral treatment: replication of the UCLA model in a community setting. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(2 Suppl):S145–55. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200604002-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: the Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):e17–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris SL, Handleman JS. Age and IQ at intake as predictors of placement for young children with autism: a four- to six-year follow-up. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30(2):137–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1005459606120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovaas OI. Behavioral treatment and normal educational and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55(1):3–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reichow B. Overview of meta-analyses on early intensive behavioral intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(4):512–20. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1218-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Remington B, Hastings RP, Kovshoff H, degli Espinosa F, Jahr E, Brown T, et al. Early intensive behavioral intervention: outcomes for children with autism and their parents after two years. Am J Ment Retard. 2007;112(6):418–38. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[418:EIBIOF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith T, Groen AD, Wynn JW. Randomized trial of intensive early intervention for children with pervasive developmental disorder. Am J Ment Retard. 2000;105(4):269–85. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2000)105<0269:RTOIEI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren Z, McPheeters ML, Sathe N, Foss-Feig JH, Glasser A, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. A systematic review of early intensive intervention for autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1303–11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh GK, Perrin JM, van Dyck PC. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005–2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):e1149–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheldrick RC, Perrin EC. Medical home services for children with behavioral health conditions. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(2):92–9. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cdabda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas KC, Parish SL, Rose RA, Kilany M. Access to care for children with autism in the context of state Medicaid reimbursement. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(8):1636–44. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0862-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montes G, Halterman JS. Association of childhood autism spectrum disorders and loss of family income. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e821–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hodgetts S, McConnell D, Zwaigenbaum L, Nicholas D. The impact of autism services on mothers’ occupational balance and participation. OTJR (Thorofare N J) 2014;34(2):81–92. doi: 10.3928/15394492-20130109-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomon M, Ono M, Timmer S, Goodlin-Jones B. The effectiveness of parent-child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(9):1767–76. doi: 10.1007/s10803-008-0567-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brookman-Frazee L, Koegel R. Using parent/clinician partnerships in parent education programs for children with autism. J Posit Behav Interv. 2004;6(4):195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gould E. Decomposing the effects of children’s health on mother’s labor supply: is it time or money? Health Econ. 2004;13(6):525–41. doi: 10.1002/hec.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Richard P, Gaskin DJ, Alexandre PK, Burke LS, Younis M. Children’s emotional and behavioral problems and their mothers’ supply. Inquiry. 2014;51:1–13. doi: 10.1177/0046958014557946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cidav Z, Marcus SC, Mandell DS. Implications of childhood autism for parental employment and earnings. Pediatrics. 2012;129(4):617–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitchener M, Carrillo H, Harrington C. Medicaid community-based programs: a longitudinal analysis of state variation in expenditures and utilization. Inquiry. 2003;40(4):375–89. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velott DL, Agbese E, Mandell D, Stein BD, Dick AW, Yu H, et al. Medicaid 1915(c) home- and community-based services waivers for children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2016;20(4):473–82. doi: 10.1177/1362361315590806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leslie DL, Iskandarani K, Dick AW, Mandell DS, Yu H, Velott D, et al. The effects of Medicaid home and community-based services waivers on unmet needs among children with autism spectrum disorder. Med Care. 2017;55(1):57–63. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blumberg SJ, Welch EM, Chowdhury SR, Upchurch HL, Parker EK, Skalland BJ. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2005–2006. Vital Health Stat. 2008;1(45):1–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bramlett MD, Blumberg SJ, Ormson AE, George JM, Williams KL, Frasier AM, et al. Design and operation of the National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009–2010. Vital Health Stat. 2014;1(57):1–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Mental health in the United States: parental report of diagnosed autism in children aged 4–17 years—United States, 2003–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(17):481–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peele PB, Lave JR, Kelleher KJ. Exclusions and limitations in children’s behavioral health care coverage. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(5):591–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Autism Speaks. State initiatives [Internet] New York (NY): Autism Speaks; [cited 2016 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.autismspeaks.org/state-initiatives. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatterji P, Decker SL, Markowitz S. The effects of mandated health insurance benefits for autism on out-of-pocket costs and access to treatment. J Policy Anal Manage. 2015;34(2):328–53. doi: 10.1002/pam.21814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Clarification of Medicaid coverage of services to children with autism [Internet] Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2014. Jul 7, [cited 2016 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/Federal-Policy-Guidance/Downloads/CIB-07-07-14.pdf. [Google Scholar]