Abstract

Recently studies have shown that, depending on the type of training and its duration, the expression levels of selected circulating myomiRNAs (c-miR-27a,b, c-miR-29a,b,c, c-miR-133a) differ and correlate with the physiological indicators of adaptation to physical activity. To analyse the expression of selected classes of miRNAs in soccer players during different periods of their training cycle. The study involved 22 soccer players aged 17-18 years. The multi-stage 20-m shuttle run test was used to estimate VO2 max among the soccer players. Samples serum were collected at baseline (time point I), after one week (time point II), and after 2 months of training (time point III). The analysis of the relative quantification (RQ) level of three exosomal myomiRNAs, c-miRNA-27b, c-miR-29a, and c-miR-133, was performed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) at three time points – before the training, after 1 week of training and after the completion of two months of competition season training. The expression analysis showed low expression levels (according to references) of all evaluated myomiRNAs before the training cycle. Analysis performed after a week of the training cycle and after completion of the entire training cycle showed elevated expression of all tested myomiRNAs. Statistical analysis revealed significant differences between the first and the second time point in soccer players for c-miR-27b and c-miR-29a; between the first and the third time point for c-miR-27b and c-miR-29a; and between the second and the third time point for c-miR-27b. Statistical analysis showed a positive correlation between the levels of c-miR-29a and VO2 max. Two months of training affected the expression of c-miR-27b and miR-29a in soccer players. The increased expression of c-miR-27b and c-miR-29 with training could indicate their probable role in the adaptation process that takes place in the muscular system. Possibly, the expression of c-miR-29a will be found to be involved in cardiorespiratory fitness in future research.

Keywords: miRNA-27b, miRNA-29a, miRNA-133, adaptation to physical activity, miRNA expression

INTRODUCTION

MiRNAs have been identified as small regulators of gene expression by repressing specific target genes at the post-transcriptional level [1, 2]. A single gene can be regulated by multiple miRNAs, and, likewise, a single miRNA may regulate several target genes that are often grouped in a specific biological pathway [3]. Important roles of miRNAs have emerged in the control of metabolic pathways involved in lipid and glucose metabolism [4], energy homeostasis and nutrition [5]. MiRNAs have the ability to control cell proliferation and apoptosis and are located at fragile sites in the genome regions [6].

An interesting feature of miRNA activity is that while miRNAs are often moderate regulators under homeostatic conditions, their function becomes more amplified in response to injury or excessive stress [7]. Moreover, miRNAs have been identified as intracellular modulators of mitochondrial metabolism, inflammation, muscle recovery and hypertrophy. These findings attracted the attention of sports scientists and started the research on miRNA regulation in exercise physiology [8]. The identification of miRNA expression patterns characteristic for physical exercise could be used to monitor physical fatigue and recovery, and even to evaluate physical performance capacity [9]. Moreover, some miRNAs (c-miRNAs) are potential markers of doping manipulations [10].

Physical activity and exercise training induce changes in extracellular and intracellular signalling that influence the expression of genes controlling inflammation, angiogenesis, mitochondrial synthesis, myocardial and skeletal muscle metabolism, regeneration and remodelling [11-14].

The level of soccer ability depends on many factors. Technical drills/technical skills and physical capacity seem to be very important components of a player’s competence. The monitoring and analysis of the training process is an indispensable part of coaching the young players. The volume and intensity of the training are the primary determinants of the training load. Training volume in sports such as soccer is defined as the total duration in minutes or as the number of repetitions of an exercise [15]. The second component of the training load is usually described using heart rates and lactate concentration measures or ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) [16-20]. Moreover, some bimolecular markers, e.g. miRNAs and c-miRNAs, have been identified as intracellular modulators of physical exercises, suggesting their role in measuring the training load or as mediators of exercise training-induced adaptations [21-22].

Long-term endurance training induces many physiological adaptations in both the central and peripheral systems. The physiological adaptations in the central cardiovascular system mainly involve decreased heart rate, increased stroke volume of the heart [23], and increased blood plasma volume without any major changes in red blood cell count. The last item reduces blood viscosity and increases cardiac output. Moreover, this type of training leads to an increase in the total mitochondrial volume and an increase in the maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) [23].

Circulating miRNAs (c-miRNAs) are also small non-coding RNA molecules that are secreted by cells in membrane-enclosed particles that include exosomes or microvesicles, bound to proteins. C-miRNAs have recently been identified extracellularly in body fluids, and differences in peripheral c-miRNA profiles have been observed in several diseases [24]. Furthermore, c-miRNAs have been found to be stable through digestion by ribonucleases (RNases), repeated freeze– thaw cycles, and prolonged storage [24]. These properties mean that extracellular miRNAs (e.g. circulating, exosomal miRNAs) may have potential for use in diagnostic and prognostic testing, as well as in identifying novel pathways and molecular mechanisms of sports. This is why we decided to investigate the effects of training on exosomal miRNA levels. So far, only one prior study has examined the effect of exercise on microRNAs specifically isolated from extracellular vesicles [25].

Expression levels of all the miRNAs we study may fluctuate (increase or decrease) depending on the regulation of particular biological processes involved in physical training. Among these miRNAs, miR-29a, miR-133a-1/-2-3p, let-7a-1/-2-5p, miR-27b-3p, miR-26a-5p, miR-1-3p, and let-7f-1/-2-5p are closely related to myogenesis, cell growth, myocyte proliferation, and cell apoptosis [26].

MiR-27a/b, a potential regulator of myogenesis, could induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy by down-regulating myostatin, an inhibitor of myogenesis [8, 27]. MiR-27b inhibition leads to increased proliferation and delays the onset of differentiation [28].

The miRNA-29 family (29a, 29b, and 29c) targets mRNAs that encode collagens and other proteins involved in fibrosis. Van Rooij et al. [29] validated target genes of the miRNA-29 family involved in cardiac fibrosis that play an important role in fibrosis during cardiac remodelling after myocardial infarction.

MiR-133a belongs to the class of muscle-specific miRNAs (myomiRNA) [30] that play a central role in the regulation of myogenesis [31]. This type of miRNA is important in skeletal muscle plasticity because it causes changes in fibre type I/II synthesis and muscle mass regulation in response to activity [26]. Predominantly, miR-133a is a key factor of proliferation and differentiation of cultured myoblasts in vitro [32].

We aimed to examine whether expression levels of three myomiRNAs differed at three time points (I – first, II – second, and III – third time point) during a two-month training cycle. We also investigated the association between myomiRNA levels and VO2 max (VO2 max was measured at the first and third time points). Potential expression level differences may support the occurrence of physiological adaptations among individuals during soccer training.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material

The study was approved by the Medical University of Lodz Ethics Committee (RNN/157/16/KE). All participants gave full written informed consent prior to study commencement.

Twenty-two young soccer players entered the experiment (age 17.5±0.70 years, height 178±0.70 cm, weight 68.05±9.18 kg). They showed high sport competence and participated in the junior Regional League in Poland. The experiment was performed in spring during the two-month training cycle of the competition season from the middle of April to the middle of June.

Methods

All the players were subjected to the same football training that involved endurance, speed and strength drills (Table 1). Small-sided games and interval runs at anaerobic threshold (AnT) were performed on a natural grass field. The intensity of the effort yielded was determined by measuring the heart rate (HR) that was equal to or higher than the AnT value, but did not exceed 90% HRmax. Individual maximal intensity and lactate threshold of the players running were determined as previously described [33] on a synthetic field at the beginning of the experiment. The test protocol included 3.5–5 min running stages separated by a 1-min rest, during which a capillary blood sample was taken from the fingertip. The initial speed was set at 2.8 m∙s-1 and increased by 0.4 m∙s-1 after each stage until exhaustion. The Dmax method [34] was used to determine the lactate threshold (V/LT) running velocity and HR/LT. Blood samples were conducted using the Random Access Automatic Biochemical Analyzer for Clinical Chemistry and Turbidimetry A15 (BIO-SYSTEMS S.A.). Lactate concentration was measured using the Rx Monza LC 2389 kit. The manufacturer stated that the method’s intra-assay coefficient of variation (CV) is 3.62%. Moreover, the maximal heart rate (HRmax) was determined during the test. If a higher HR value was observed during the small-sided games, the higher value was used as the HRmax. An overview of the typical weekly training load during the experiment is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Overview of typical weekly training load during experiment.

| Day of week | Morning | Afternoon | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training drills | Intensity (%HRmax) | Duration (min) | Training drills | Intensity (%HRmax) | Duration(min) | |

| Monday | Free | - | - | aerobic exercises, coordination, technical | 70 | 90 |

| Thursday | plyometric and speed, technical | 85 | 80 | small-sided games, tactical | 90 | 90 |

| Wednesday | Free | - | - | coordination, technical,tactical | 70 | 100 |

| Thursday | Free | - | - | technical, tactical | 75 | 90 |

| Friday | coordination, technical | 70 | 75 | interval run, tactical | 80 | 90 |

| Saturday | Competition game | |||||

| Sunday | Free day | |||||

Beep test

The multi-stage 20-m shuttle run test was used to estimate the VO2 max among soccer players. The test involved running continuously between two points 20 m apart. These runs were synchronized with a pre-recorded audio tape, CD or laptop software, that played beeps at set intervals. As the test proceeded, the interval between each successive beep was reduced, forcing the soccer players to increase their speed over the course of the test, until it was impossible to keep in sync with the recording (or, in rare occasions, if the player completed the test). The recording was typically structured into 21 ‘levels’, each of which lasted around 62 seconds. The interval of beeps was calculated to require a speed of 8.5 km/h at the start, which then had to increase by 0.5 km/h with each level thereafter. The progression from one level to the next was signalled by 3 rapid beeps. The highest level attained before failing to keep up was recorded as the score for that test [35-36].

Serum collection

Participants visited the laboratory in a fasted state and at least 12 h after exercise. After reporting to the laboratory at a standardized time (between 8 and 10 a.m., intra-individually the same hour for all tests) athletes rested in the supine position for 10 min prior to blood collection. A winged cannula was inserted into the antecubital vein during a short stasis (max. 30 s).

Participation of the players in training sessions was 90%. Before, during, and after the experiment, the tested subjects lived in the school dormitory and were nourished in the same way (sports diet). All the subjects had valid medical cards. All subjects and their parents or guardians were provided with detailed information about the research procedures and gave their written consent.

Samples were collected at baseline (time point I), after one week (time point II), and after 2 months of training (time point III). Blood was collected in Eppendorf tubes and left for about 30-45 minutes at 37°C (until clot formation). Then it was placed in a refrigerator at a temperature of 4°C for several hours (0.5-4 h) until the total organization of the clot. Next, the tube was centrifuged (1200 x g 10 min, 4°C), and serum was separated from the clot carefully into a new sterile tube, frozen and stored at -80°C.

RNA extraction and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis

All molecular and statistical analyses were conducted at the Medical University of Lodz. RNA was extracted from serum exosomes using the Total Exosome Isolation Reagent (from serum) and Total Exosome RNA & Protein Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a starting volume of 200 μL. From the resulting RNA eluate, cDNA was synthesized using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) using 5 μl of template RNA. cDNA products were diluted up to 250 μL with double-distilled water and loaded on plates for storage at -20°C until further analysis.

miRNA analysis

Commercially available primer assays (Applied Biosystems, USA) were used for quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) in miRNA analysis (target miRNAs: c-miR-27b, c-miR-29a, c-miR-133; control miRNAs: RNU6B). The candidate miRNAs measured in the present study were selected due to their reported upregulation at rest in response to endurance rowing training and for their status as myomiRNAs [37-39]. MiRNA levels were measured in triplicate, using the synthesized cDNA with the TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA). The qPCR mixture contained: cDNA (1 to 100 ng), 20× TaqMan miRNA Expression Assay, TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix, and RNase-free water in a total volume of 20 µl. The qPCR reactions were performed in the Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System for 39 cycles, with an annealing temperature of 60°C, repeated 3 times for each sample. The relative expression of the studied samples was assessed using the comparative delta-delta CT method (TaqMan Relative Quantification Assay software) and presented as RQ values, adjusted to the RNU6B expression level.

Five control assays (let-7a-5p, miR-9, miR-21, miR-122, RNU6B) were selected based on previous reports showing expression stability within plasma. Norm finder software was used to determine which single gene or group of genes was at the most stable level within the samples. RNU6B alone was found to be most stable across the three groups and was therefore used to determine the relative expression of the target genes, calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method. Consistent with RNU6B being the most stable miRNA between groups, data from other reports indicate that the other 4 miRNAs may not have been good candidates for controlling genes due to their association with other stimuli including cancer.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed in order to evaluate the differences between the expression levels (RQ values) of the studied miRNAs (c-miRNA-27b, c-miRNA-29a, c-miRNA-133) at the three time points. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to find relationships between the expression levels of the studied miRNAs and VO2 max. In this study all statistical analyses were performed using the Statistica 12.0 program.

RESULTS

The average values of VO2 max at the studied time points were calculated. At the first time point, i.e., before the cycle training, the average value was 51.28 (ml/kg/min); at the third time point, i.e., after the training cycle, the average value was 54.93 (ml/kg/min). General characteristics of the subjects are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and physiological characteristics of subjects.

| Soccer players’ first time point | Soccer players’ second time point | Soccer players’ third time point | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17±0.68 | 17±0.68 | 17±0.68 |

| Weight | 69±9.55 | ----- | 69±9.15 |

| Height | 178±6.96 | 178±6.96 | 178±6.96 |

| VO2 | 51.28±3.71 | ----- | 54.93±3.00 |

The obtained results showed lower expression levels of all studied myomiRNAs in relation to the calibrator at the first time point: c-miRNA-27b (RQ = 0.34), c-miRNA-29a (RQ = 0.56) and c-miRNA-133 (RQ = 0.64). Analysis of the expression levels of the studied miRNAs at the second time point showed elevations in each case: c-miRNA-27b (RQ = 1.22), c-miRNA-29a (RQ = 1.75) and c-miRNA-133 (RQ = 1.32). After completion of the entire training cycle (third time point), analysis showed once again an increase in expression levels for all studied myomiRNAs: c-miRNA-27b (RQ = 2.53), c-miRNA-29a (RQ = 4.12) and c-miRNA-133 (RQ = 1.49).

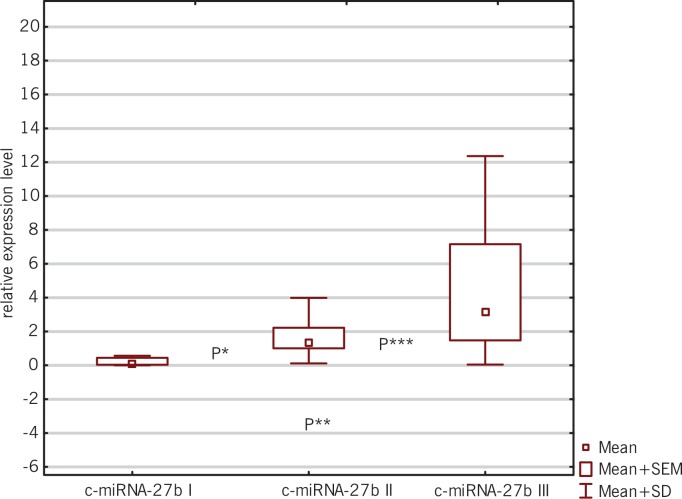

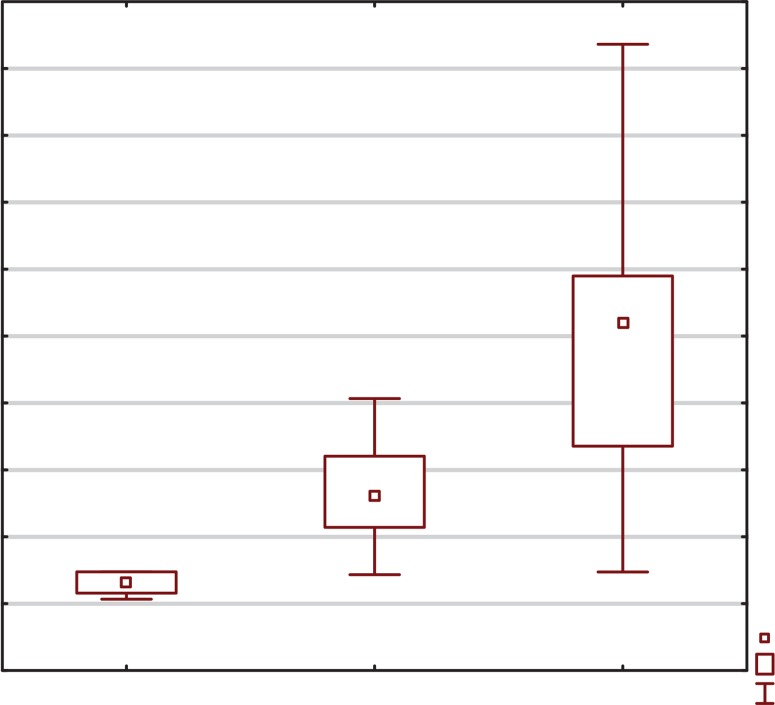

Statistical significance was obtained between the first and the second time point for c-miRNA-27b (P = 0.0098; Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and c-miRNA-29a (P = 0.0220; Wilcoxon signed-rank test); between the first and third time point for c-miRNA-27b (P = 0.0003; Wilcoxon signed-rank test) and c-miRNA-29a (P = 0.0241; Wilcoxon signed-rank test); and between the second and the third time point for c-miRNA-27b (P = 0.0016; Wilcoxon signed-rank test), as presented in Figures 1, 2, and 3.

FIG. 1.

Box-and-whisker plots representing the expression levels (mean RQ) of c-miRNA-27b at three time points (I-III).

P* = 0.0098; between the first and second time point for c-miRNA-27b

P**=0.0003; between the first and third time point for c-miRNA-27b

P***=0.0016; between the second and third time point for c-miRNA-27b

FIG. 2.

Box-and-whisker plots representing the expression levels (mean RQ) of c-miRNA-29a at three time points (I-III).

P****=0.0220; between the first and second time point for c-miRNA-29a

P*****=0.0241; between the first and third time point for c-miRNA-29a

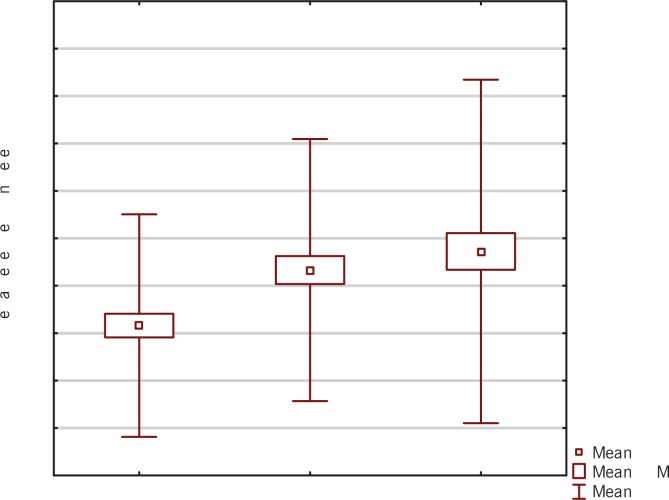

FIG. 3.

Box-and-whisker plots representing the expression levels (mean RQ) of c-miRNA-133 at three time points (I-III).

We did not find any significant correlations between the second and the third time point for c-miRNA-29a and at any time points for c-miRNA-133 (P>0.05; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

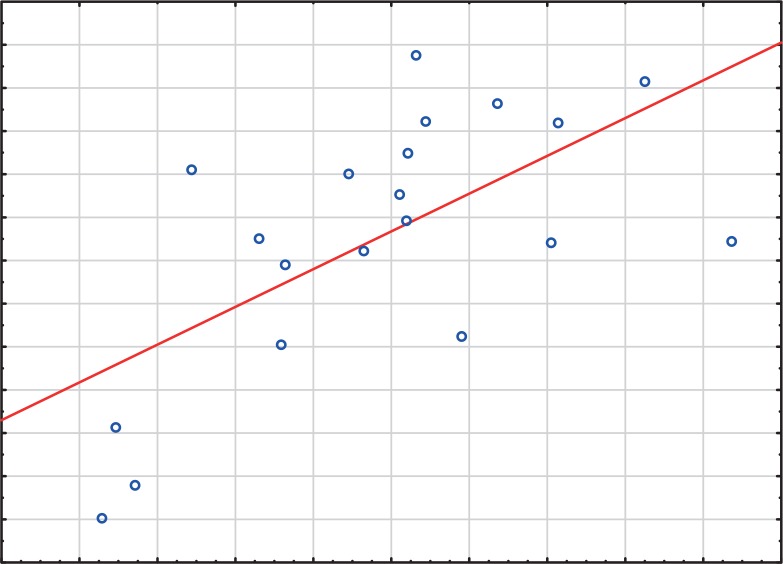

Finally, we assessed the reciprocal relationship between the expression levels of the studied miRNAs and VO2 max.

Statistical analysis showed a positive correlation between the expression level of c-miRNA-29a and VO2 max (R = 0.54, P =0.008; Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient) at the third time point (Figure 4). There was no statistically significant correlation between other studied myomiRNAs and VO2 max at any of the time points.

FIG. 4.

Line graph representing the correlation between the expression levels (mean RQ) of c-miRNA-29a and VO2 max (R = 0.54, P = 0.008).

DISCUSSION

MiRNAs can be considered as molecular biomarkers related to the type of training – some of them correlate with exercise capacity and/or anthropometric characteristics and/or biochemical markers. We believe that molecular analysis would allow optimization of the training process and would contribute to the players’ harmonious development.

The identification of miRNA expression patterns characterizing physical exercise could be applied for monitoring physical fatigue and recovery, and even for evaluating physical performance capacity [9]. Moreover, as circulating miRNAs (c-miRNAs) are of tissue or cellular origin, they seem to be potential markers of adaptation to physical activity. So far, there has been only one published study regarding the effects of exercise on microRNAs specifically isolated from extracellular vesicles [32]. Our study is the second such study to assess the effects of training on exosomal miRNAs.

In our study we found significantly increased expression of c-miR-27b between all three measured points (the first and the second; the second and the third; the first and the third). There are no available published data concerning the association between c-miRNA-27b expression and performance parameters in sport.

Studies have shown that a higher expression level of miR-27b may serve as a preventive marker of cartilage degeneration. It was found that higher expression of miR-27b plays a role in prevention of cartilage degeneration after impact injury (ex-vivo animal knee joint model) [40]. The same author observed prolonged decreased expression of miR-27b in knee osteoarthritis [41], also suggesting a diagnostic role for miR-27b (an early diagnostic marker in osteoarthritis). Unfortunately, we did not examine the correlation between c-miR-27b and injury, because none of the players had suffered an injury. Also in our study c-miR-27b was not decreased, thus suggesting that in our group of soccer players there were no microinjuries. Moreover, miR-27a/b, a potential regulator of myogenesis, could induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy [25-26]; however, we did not study muscle strength.

It has been suggested that regenerative processes are heavily regulated by microRNAs. During the 8-week long training cycle, we also observed increased and persistent expression of c-miR-27b, which might show a correlation between this miRNA and the regeneration process of muscles and articular cartilage.

During the 8-week long training cycle we also observed an increased expression level of c-miR-29a. Moreover, we documented significantly increased expression levels of c-miR-29a between both the first and the second, and the first and the third time points. A study using an animal model showed that rats subjected to swim training presented physiological cardiac hypertrophy and increased expression of miR-29a in their hearts, which correlated linearly with an increase in training duration [42]. In our study we documented prolonged high levels of miRNA expression in soccer players after training. These data suggest that the beginning of the regeneration process occurred in response to micro injures. Indeed, Galimows et al. [43] also suggested that miR-29a overexpression regulated the generation process of skeletal muscle in their animal model. It has been shown that during the proliferation of activated satellite cells in the muscle regeneration process, high expression of miR-29a might be induced by FGF2 [43].

The expression levels of some miRNAs were significantly associated with performance parameters of training mode, such as VO2 max. Literature reports indicate that the beep test is used as a measure of aerobic capacity in soccer players [44-45]; however, it is known that this test is not a gold standard measure of aerobic capacity. We have also documented that an 8-week long training cycle leads to changes in the expression level of c-miRNA-29a. Additionally, a positive correlation between the expression level of c-miR-29a and VO2 max has been documented. Unfortunately, we cannot compare our results to others, because so far such a correlation in athletes has not been studied. Published data confirm that athletes’ efficiency is heavily regulated by microRNAs. Our results suggested that c-miR-29a might be considered a cell efficiency marker, as the players with increased c-miRNA-29a also had increased VO2 max. However, the study conducted by Bye et al. [46] on a group 24 people cultivating aerobic fitness did not reveal any associations between c-miRNA-29a and VO2 max.

We did not observe any statistically significant associations between the expression of c-miR-133 and VO2 max at any studied time points. The studies of other authors have shown that in marathon runners miR-133a was increased after a marathon and a positive correlation with VO2 max was also observed [47-48].This study showed that c-miR-133a could be a potential biomarker of adaptation to exercise. Unfortunately, our study did not confirm that.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study indicates that observing the expression levels of some classes of miRNAs may be helpful in the monitoring of training. Specifically, MiRNAs could act as molecular indicators of adaptive changes in muscles and the respiratory system during exercise. Due to the difficulties in the standard methods of assessment, this molecular monitoring is a very useful diagnostic method in evaluating adaptation and the regeneration process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mendell JT, Olson EN. microRNAs in stress signaling and human disease. Cell. 2012;148:1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poy MN, Spranger M, Stoffel M. microRNAs and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolte-’t Hoen EN, Van Rooij E, Bushell M, Zhang CY, Dashwood RH, James WPT, Harris C, Baltimore D. The role of microRNA in nutritional control. J Intern Med. 2015;278:99–109. doi: 10.1111/joim.12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee EJ, Baek M, Gusev J, Brackett DJ, Nuovo GJ, Schmittgen TD. Systematic evaluation of microRNA processing patterns in tissues, cell lines, and tumors. RNA. 2008;14:35–42. doi: 10.1261/rna.804508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leung AK, Sharp PA. MicroRNA functions in stress responses. Mol Cell. 2010;40:205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma M, Juvvuna PK, Kukreti H, McFarlane C. Mega roles of microRNAs in regulation of skeletalmuscle health and disease. Front Physiol. 2014;5:239. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kangas R, Pöllänen E. Physical activity responsive miRNAs—Potential mediators of training responses inhuman skeletal muscle? J Sport Health Sci. 2013;2:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leuenberger N, Schumacher YO, Pradervand S, Sander T, Saugy M, Pottgiesser T. Circulating microRNAs as biomarkers for detection of autologous blood transfusion. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Egan B, Zierath JR. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. CellMetab. 2013;17:162–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gundersen K. Excitation-transcription coupling in skeletal muscle: The molecular pathways of exercise. Biol Rev. 2011;86:564–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00161.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Camera DM, Smiles WJ, Hawley JA. Exercise-induced skeletal muscle signaling pathways and humanathletic performance. Free RadicBiol Med. 2016;98:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denham J, Marquez FZ, O’Brien BJ, Charchar FJ. Exercise: Putting action into our epigenome. Sports Med. 2014;44:189–209. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGuigan MR, Foster C. A new approach to monitoring resistance training. Strength Cond. 2004;26(6):42–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eniseler N. Heart rate and blood lactate concentrations as predictors of physiological load on elite soccer players during various soccer training activities. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19(4):799–804. doi: 10.1519/R-15774.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dellal A, Chamari K, Pintus A, Girard O, Cotte T, Keller D. Heart rate responses during small-sided games and short intermittent running training in elite soccer players: a comparative study. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(5):1449–1457. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31817398c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foster CD, Twist C, Lamb KL, Nicholas CW. Heart rate responses to small-sided games among elite junior rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res. 2001;24(4):906–911. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181aeb11a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dellal A, Keller D, Carling C, Chaouachi A, Wong DP, Chamari K. Physiologic effects of directional changes in intermittent exercise in soccer players. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24(12):3219–26. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181b94a63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Głowacki A, Ignatiuk W, Konieczna A, Jastrzębski Z. Training Load Structure of Young Soccer Players in a Typical Training Microcycle during the Competitive and the Transition Period. Baltic Journal of health and physical activity. 2011;3(1):26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polakovičová M, Musil P, Laczo E, Hamar D, Kyselovič J, Taguchi Y. Academic Editor Circulating MicroRNAs as Potential Biomarkers of Exercise Response. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 Oct;17(10):1553. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Liu, Xie Y, Zhao C, Wang H. Bioinformatics Analysis Reveals MicroRNAs Regulating Biological Pathways in Exercise-Induced Cardiac Physiological Hypertrophy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:2850659. doi: 10.1155/2017/2850659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noakes TD. Physiological models to understand exercise fatigue and the adaptations that predict or enhance athletic performance. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2000;10:123–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2000.010003123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:10513–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guescini M, Canonico B, Lucertini F, Maggio S, Annibalini G, Barbieri E, Luchetti F, Papa S, Stocchi V. Muscle Releases Alpha-Sarcoglycan Positive Extracellular Vesicles Carrying miRNAs in the Bloodstream. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy JJ, Esser KA. MicroRNA-1 and microRNA-133a expression are decreased during skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J ApplPhysiol (1985). 2007;102(1):306–13. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00932.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang Z, Chen X, Yu B, He J, Chen D. MicroRNA-27a promotes myoblastproliferation by targeting myostatin. BiochemBiophys Res Commun. 2012;423(2):265–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crist CG, Montarras D, Pallafacchina G, Rocancourt D, Cumano A, Conway SJ, Buckingham M. Muscle stem cell behavior is modified by microRNA-27 regulation of Pax3 expression. Proc Natl AcadSci U S A. 2009;106(32):13383–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900210106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, DiMaio JM, Naseem RH, Marshall WS, Hill JA, Olson EN. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl AcadSci USA. 2008;105:13027–13032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805038105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Callis TE, Deng Z, Chen JF, Wang DZ. Muscling through the microRNA world. ExpBiol Med. 2008;233:131–8. doi: 10.3181/0709-MR-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge Y, Sun Y, Chen J. IGF-II is regulated by microRNA-125b in skeletal myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:69–81. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radziminski L, Rompa P, Dargiewicz R, Ignatiuk W, Jastrzebski Z. An application of incremental running test results to train professional soccer players. Baltic Journal of Health and Physical Activity. 2010;2:67–74. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng B, Kuipers H, Snyder A.C, Keizer H.A, Jeukendrup A, Hesselink M. A new approach to the determination of ventilatory and lactate thresholds. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 1992;13:518–522. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1021309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leger L.A, Lambert J. “A maximal multistage 20m shuttle run test to predict VO2 max”. Eur J ApplPhysiolOccupPhysiol. 1982;49(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00428958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Léger L.A, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. “The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness”. J Sports Sci. 1988;6(2):93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandes T, Hashimoto NY, Magalhães FC, Fernandes FB, Casarini DE, Carmona AK, Krieger JE, Phillips MI, Oliveira EM. Aerobic exercise training-induced left ventricular hypertrophy involves regulatory MicroRNAs, decreased angiotensin-converting enzyme-angiotensin ii, and synergistic regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2-angiotensin (1-7) Hypertension. 2011;58:182–189. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.168252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nielsen S, Åkerström T, Rinnov A, Yfanti C, Scheele C, Pedersen BK, Laye MJ. The miRNA plasma signature in response to acute aerobic exercise and endurance training. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wardle SL, Bailey ME, Kilikevicius A, Malkova D, Wilson RH, Venckunas T, Moran CN. Plasma microRNA levels differ between endurance and strength athletes. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Genemaras AA, Reiner T, Huang CY, Kaplan L. Early intervention with Interleukin-1 Receptor Antagonist Protein modulates catabolic microRNA and mRNA expression in cartilage after impact injury. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(11):2036–44. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Genemaras AA, Ennis H, Kaplan L, Huang CY. Inflammatory cytokines induce specific time- and concentration-dependent MicroRNA release by chondrocytes, synoviocytes, and meniscus cells. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(5):779–90. doi: 10.1002/jor.23086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Melo SF, Fernandes T, Baraúna VG, Matos KC, Santos AA, Tucci PJ, Oliveira EM. Expression of MicroRNA-29 and Collagen in Cardiac Muscle after Swimming Training in Myocardial-Infarcted Rats. CellPhysiolBiochem. 2014;33(3):657–69. doi: 10.1159/000358642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Galimov A, Merry TL, Luca E, Rushing EJ, Mizbani A1, Turcekova K, Hartung A, Croce CM, Ristow M, Krützfeldt J. MicroRNA-29a in Adult Muscle Stem Cells Controls Skeletal Muscle Regeneration During Injury and Exercise Downstream of Fibroblast Growth Factor-2. Stem Cells. 2016;34(3):768–80. doi: 10.1002/stem.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leger LA, Lambert J. A maximal multistage 20m shuttle run test to predict VO2 max. Eur J ApplPhysiolOccupPhysiol. 1982;49(1):1–12. doi: 10.1007/BF00428958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Léger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C, Lambert J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci. 1988;6(2):93–101. doi: 10.1080/02640418808729800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bye A, Røsjø H, Aspenes ST, Condorelli G, Omland T, Wisløff U. Circulating microRNAs and aerobic fitness-the HUNT-Study. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57496. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gomes CP, Oliveira-Jr GP, Madrid B, Almeida JA, Franco OL, Pereira RW. Circulating miR-1, miR-133a, and miR-206 levels are increased after a half-marathon run. Biomarkers. 2014;19(7):585–9. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.952663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baggish AL, Park J, Min PK, Isaacs S, Parker BA, Thompson PD, Troyanos C, D’Hemecourt P, Dyer S, Thiel M, Hale A, Chan SY. Rapid upregulation and clearance of distinct circulating microRNAs after prolonged aerobic exercise. J ApplPhysiol (1985). 2014;116(5):522–31. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01141.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]