Abstract

Background

Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt), an under-appreciated cause of heart failure in older adults, is challenging to diagnose and monitor in the absence of validated, disease-specific biomarkers. We examined the prognostic utility and survival association of serum transthyretin (TTR) concentration in ATTRwt.

Methods and Results

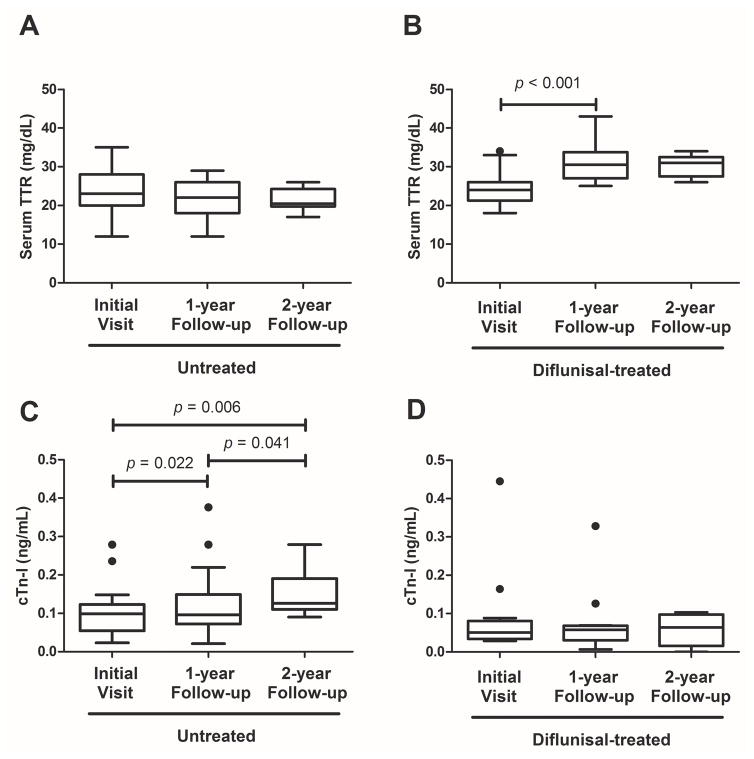

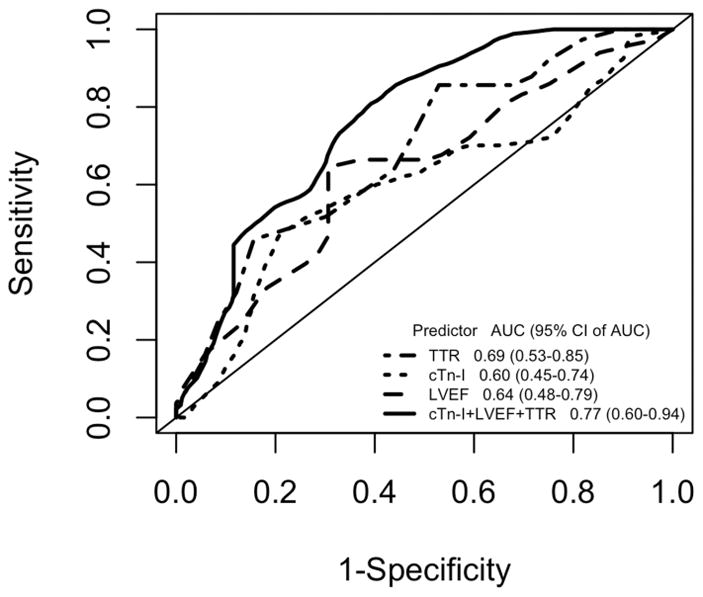

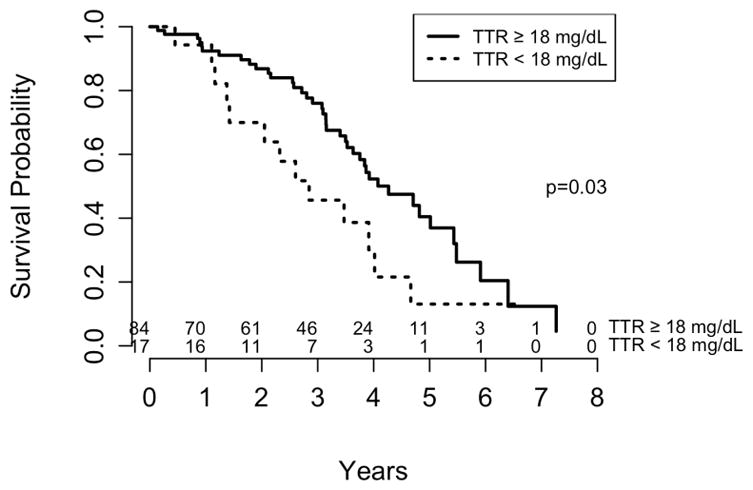

Patients with biopsy-proven ATTRwt were retrospectively identified. Serum TTR, cardiac biomarkers, and echocardiographic parameters were assessed at baseline and follow-up evaluations. Statistical analyses included Kaplan-Meier method, Cox proportional hazard survival models, and receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Median serum TTR concentration at presentation was 23 mg/dL (n=116). Multivariate predictors of shorter overall survival were decreased TTR and LVEF, and elevated cTn-I; an inclusive model demonstrated superior accuracy in 4-year survival prediction by ROC analysis (area under the curve, 0.77). TTR values lower than the normal limit, <18 mg/dL, were associated with shorter survival (2.8 vs. 4.1 years, p=0.03). Further, TTR values at 1- and 2-year follow-ups were significantly lower (p<0.001) in untreated patients (n=23) compared to those treated with TTR stabilizer, diflunisal (n=12), following baseline evaluation. During 2-year follow-up, unchanged TTR corresponded to increased cTn-I (p=0.006) in untreated patients; conversely the diflunisal-treated group showed increased TTR (p=0.001) and stabilized cTn-I and LVEF at 1-year.

Conclusions

In this series of biopsy-proven ATTRwt amyloidosis, lower baseline serum TTR concentration was associated with shorter survival as an independent predictor of outcome. Longitudinal analysis demonstrated decreasing TTR corresponded to worsening cardiac function. These data suggest TTR may be a useful prognostic marker and predictor of outcome in ATTRwt amyloidosis.

Journal subject terms: biomarkers, aging, risk factors, cardiomyopathy, heart failure

Keywords: amyloid, heart failure, risk factor, survival, biomarker

Introduction

Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt) is a sporadic, fatal protein misfolding disease characterized by extracellular cardiac deposition of ordered fibrils composed of wild-type transthyretin (TTR).1–4 Formerly known as prealbumin, TTR is a liver-secreted plasma protein that functions as a minor carrier of thyroxine and binding partner to retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4).5,6 Serum concentrations, normally 18–45 mg/dL,7 are dependent on age, sex, race and nutritional status; moreover, TTR levels can fluctuate as a consequence of infection or generalized inflammatory states.8–10 Several studies have shown significantly decreased TTR concentrations in inherited forms of TTR amyloidosis (ATTRm) and lower-range normal levels in a single small ATTRwt series.8,11–13

ATTRwt is most commonly diagnosed in older adults with cardiomyopathy and typical heart failure symptoms1–3,14; median survival from onset of symptoms is reportedly < 5 years.15 While prevalence in the general population is unknown, ATTRwt cardiomyopathy is likely under-recognized, as the clinical features overlap with other forms of cardiac amyloid, and can mimic cardiac pathologies that frequently coexist in advanced age such as hypertensive or hypertrophic heart diseases.16–20 Several studies demonstrated the presence of TTR amyloid fibrils in 10–25% of post-mortem hearts from individuals over age 80 years, suggesting that ATTRwt may be an under-appreciated cause of heart failure in older Caucasian men with diastolic dysfunction.2,21,22 Accurate diagnosis of ATTRwt can be challenging as obtaining a biopsy from the affected tissue for histological evidence, the gold-standard in amyloid testing, can pose significant risk in elderly patients. Moreover, in the absence of biopsy proof, disease identification depends upon appropriate interpretation of echocardiography, cardiac magnetic imaging, or nuclear scintigraphy.23 Serum markers of myocardial damage, such as cardiac troponin I (cTn-I) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), have been used to support a diagnosis of ATTRwt and measure worsening cardiac status, but no definitive biomarkers of disease have been identified.24 Treatment of ATTRwt has previously been confined to cardiac transplantation, however there are currently a number of investigational agents in clinical trial that may halt TTR amyloid deposition and extend survival. One of these agents, diflunisal, stabilizes tetrameric TTR and inhibits misfolding25; diflunisal is reportedly effective for neuropathy associated with ATTRm, and, by extension, is being used clinically in selected patients with ATTRwt.26

The complexities of the diagnostic algorithm, absence of disease-specific measures of progression, and lack of consensus on risk predictors demand the development of ATTRwt biomarkers to facilitate diagnosis and disease monitoring. The goal of this study was to evaluate the utility of serum TTR concentration as a marker of ATTRwt, and to determine its prognostic value for overall survival.

Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study groups

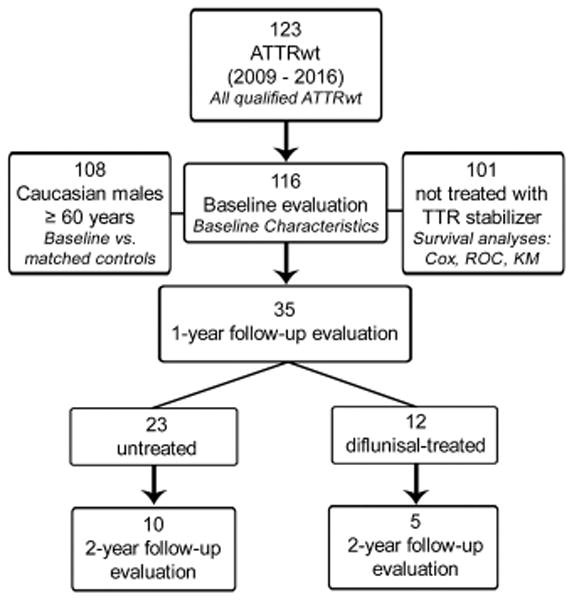

Deidentified serum samples and data from patients with ATTRwt were obtained from the Boston University Amyloidosis Center specimen repository and clinical database with written consent under approval of the Institutional Review Board at the Boston University Medical Campus in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Clinical data included details of history, physical examination, laboratory testing, and echocardiographic studies. Patients were selected from an ongoing longitudinal ATTRwt cohort evaluated at our center between January 2009 and December 2016 (Figure 1). Diagnosis of ATTRwt was based on biopsy proof of amyloid by Congo red staining and biochemical or immunochemical proof of TTR as the major component of the amyloid deposit. Sequencing of all 4 exons of the TTR gene was performed to rule out the presence of pathologic TTR mutations. Of 123 patients diagnosed with ATTRwt, 116 were included in this study; 7 were excluded for lack of adequate serum samples, incomplete clinical data for selected laboratory parameters, or due to established treatment with a TTR stabilizer at initial evaluation. For comparison of TTR concentrations at baseline, 30 control serum samples from healthy Caucasian males age ≥ 60 years were purchased from Bioreclamation (Westbury, NY) and compared to an ATTRwt sub-group matched for age, race and gender (n = 108). In addition, ATTRwt baseline values were also compared to serum TTR levels measured in a small group (n = 9) of matched patients with cardiomyopathy unrelated to amyloid. Survival analyses were conducted on 101/116 patients excluding those who were receiving TTR-stabilizing treatments at initial or follow-up evaluations; 12 were being treated with diflunisal and 3 were in clinical trials for Tafamidis27. A 1-year follow-up evaluation included 23 untreated patients, and 12 patients treated with the TTR-stabilizer, diflunisal, started after the initial visit. A 2-year follow-up evaluation included 10 untreated patients and 5 treated with diflunisal for the entire follow-up.

Figure 1. Flowchart of wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt) patient groups.

Of 123 patients diagnosed with biochemically-proven ATTRwt between January 2009 and December 2016, 116 with adequate repository samples and complete laboratory data were included in baseline studies. Of these, 108 were Caucasian males over age 60 years, to be matched to the control group; and, 101 were not treated with transthyretin (TTR) stabilizers throughout their follow-up period. The three baseline groups in tier 2 were used for certain analyses, identified by italic font in each box. Thirty-five patients were evaluated at 1-year: 23 received no treatment and 12 were treated with diflunisal. Fifteen patients were evaluated at 2-year: 10 untreated and 5 diflunisal-treated.

Clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic data were chosen based on our previous report detailing the natural history of ATTRwt.15 Serum concentrations of cTn-I, BNP, total protein, albumin, creatinine, uric acid, C-reactive protein (CRP) or sensitive CRP, and sedimentation rate were measured as part of routine laboratory testing. The CRP and sensitive CRP values were converted to dichotomous variables (normal range thresholds, <1 mg/dL and ≤5 mg/L, respectively) as measurements for each variable were not available in all patients. Echocardiographic parameters including interventricular septal thickness (IVST), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), and relative wall thickness (RWT) were derived by researchers blinded to patient diagnosis as described.15

Serum TTR measurements

Serum TTR concentrations were measured by the Boston Medical Center Pathology Department using a CLIA-approved immunoturbidimetric assay for prealbumin with coefficients of variation < 5.5% (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Serum samples were assessed immediately or stored at ≤ −20°C prior to analysis. Freezer temperature and freeze/thaw cycles had no effect on TTR concentration.

Statistical analysis

Data describing initial and follow-up evaluations including baseline characteristics, plots, and associated p-values were generated using GraphPad Prism software, version 5.02 (La Jolla, CA). Deviations from normal distribution were assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. P-values comparing treated and untreated groups were determined by unpaired, two-sided t-test with Welch’s correction or Mann-Whitney test, depending on data normality. P-values comparing within-group follow-ups were determined by paired, two-sided t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test. All t-tests were performed with a type I error rate set at α = 0.05.

Survival analyses were performed using R Foundation for Statistical Computing software, version 3.2.3 (Vienna, Austria). TTR, serologic, and echocardiographic variables were examined for associations with overall survival (OS). Univariate Cox analysis was initially performed to identify factors associated with OS, and subsequently adjusted for age, body mass index (BMI), and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class at the time of presentation. All univariate variables with p < 0.1 were included in a multivariate proportional hazards regression model; and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The sensitivities, specificities, and area under the receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve at 4 years were calculated using the Nearest Neighborhood Estimator approach by Heagerty et al. accounting for censoring in survival data.28

OS curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using a log rank test. The lower normal limit of 18 mg/dL TTR 7 was used as a threshold to stratify patients. Survival time was measured from date of positive biopsy (diagnosis) to death. Follow-up ended in December 2016 and patients who survived beyond the study period were censored.

Results

ATTRwt cohort characteristics

Baseline clinical, laboratory, and echocardiographic features in 116 patients with ATTRwt are shown in Table 1. The median age at baseline was 76.0 years (range, 51.0 – 87.8 y) (Table 1). The majority were male (97.4%) and Caucasian (96.5%). Three women exhibited similar characteristics to the remainder of the cohort with respect to age, serologic testing, and echocardiographic measures. Wild-type TTR coding region sequences were identified in all cases, with the exception of non-pathologic G6S (p.G26S), identified in 6/116 (5.2%) of the group. Consistent with our previous report,15 abdominal fat biopsy documented amyloid in 21.5% of patients. BMI was slightly elevated at 28.2 kg/m2 (range, 22.0 – 38.2 kg/m2).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical features and laboratory parameters

| Characteristic | ATTRwt (n = 116) | Normal values |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 76.0 (51.0 – 87.8) | |

| Male, n (%) | 113 (97.4) | |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 112 (96.5) | |

| Deceased (as of Dec. 2016), n (%) | 53 (45.7) | |

| TTR variant, n (%) | ||

| G6S | 6 (5.2) | |

| Positive abdominal fat biopsy, n (%) | 25 (21.5) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28.2 (25.8 – 31.8) | 18.5 – 24.9 |

| Serological Markers, median (IQR) | ||

| TTR (mg/dL) | 23 (20 – 26) | 18 – 45 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 7.1 (6.8 – 7.5) | 6.0 – 8.2 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.1 (3.9 – 4.4) | 3.5 – 4.8 |

| Sedimentation rate (mm/hr) | 12 (7 – 22) | 0 – 22 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.20 (0.99–1.53) | 0.80 – 1.30 |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 7.9 (6.0 – 9.5) | 3.4 – 7.0 |

| Abnormal CRP, n (%) | 28 (24.1) | |

| Cardiac Findings, median (IQR) | ||

| NYHA functional class II or greater, n (%) | 94 (81.0) | |

| cTn-I (ng/mL) | 0.114 (0.066 – 0.186) | 0 – 0.049 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 373 (221 – 661) | 0 – 72.3 |

| IVST (mm) | 15 (14 – 17) | < 11 |

| RWT (cm) | 0.72 (0.64 – 0.84) | 0.22 – 0.42 |

| LVEF (%) | 50 (40 – 58) | 55 – 75 |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 141.8 (119.5 – 168.2) | < 131 |

| Arrhythmia present, n (%) | 79 (68.1) | |

ATTRwt indicates wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis; n, group number; TTR, transthyretin; BMI, body mass index; IQR, inter-quartile range; CRP, c-reactive protein; NYHA, New York Heart Association; cTn-I, cardiac troponin I; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; IVST, interventricular septal thickness; RWT, relative wall thickness; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and LVMI, left ventricular mass index

Median serum TTR level at presentation was 23 mg/dL, ranging from 11 – 39 mg/dL (Table 1); moreover, a study of sera from ATTRwt and age-, gender- and race-matched healthy and non-amyloid cardiomyopathy (CMP) controls showed comparable TTR concentrations in all groups (23 vs. 24 and 25 mg/dL, p = 0.109 and 0.484, respectively; Supplemental Figure 1). In ATTRwt, median values for total protein, albumin, sedimentation rate, and creatinine were within normal ranges. CRP was abnormal in 24.1% (Table 1). Median values for serologic and echocardiographic markers of cardiac function, cTn-I, BNP, IVST, RWT, LVEF and LVMI were outside the normal range and reflected cardiac involvement (Table 1). A majority (81%) of patients presented with NYHA functional class of II or greater, and 68.1% showed evidence of arrhythmia by electrocardiography at baseline.

Overall survival and factors associated with survival

At the end of observation, 53 of 116 patients (45.7%) had died with a median time from diagnosis to death of 3.1 years (range, 0.1 – 7.3 y). The estimated median OS for the entire ATTRwt cohort (n = 116) was 4.0 years (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.6 – 5.4 y) and for untreated patients (n = 101), 3.9 years (range, 3.5 – 4.8 y); no treated patients had died by the end of observation. Parameters associated with OS in univariate analysis of untreated patients included TTR (p = 0.007), cTn-I (p < 0.001), BNP (p = 0.002), LVEF (p = 0.001), creatinine (p = 0.02), uric acid (p = 0.02), and sedimentation rate (p = 0.001) (Table 2). Multivariate analysis yielded TTR (p < 0.001), cTn-I (p < 0.001), and LVEF (p = 0.01) as indicators of shorter survival. No significant multicollinearity was observed; adjustment for baseline factors, age, BNP, and NYHA class did not affect these results. Hazard ratios for TTR obtained when controlling for several baseline variables were as follows: BMI – 0.92 (0.88–0.98), p=0.01; CRP – 0.93 (0.88–0.99), p=0.02; and both BMI and CRP – 0.94 (0.89–0.99), p=0.02.

Table 2.

Factors associated with survival in ATTRwt (n = 101)

| Variable | Univariate analysis Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Multivariate analysis Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTR (mg/dL) | 0.93 (0.88 – 0.98) | 0.007 | 0.89 (0.84 – 0.95) | < 0.001 |

| cTn-I (ng/mL) | 5.12 (2.43 – 10.81) | < 0.001 | 8.06 (3.01 – 21.57) | < 0.001 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 1.001 (1.001 – 1.002) | 0.002 | ||

| LVEF (%) | 0.96 (0.94 – 0.99) | 0.001 | 0.97 (0.94 – 0.99) | 0.01 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.02 (1.14 – 3.60) | 0.02 | ||

| Uric acid (mg/dL) | 1.14 (1.02 – 1.28) | 0.02 | ||

| Sedimentation rate (mm/hr) | 1.03 (1.01 – 1.04) | 0.001 |

ATTRwt indicates wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis; TTR, transthyretin; cTn-I, cardiac troponin I; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and CI, confidence interval

The value of single or multiple variables in predicting 4-year survival was assessed using ROC analysis (Figure 2). Individually, the area under the curve (AUC) values indicated that sensitivity was comparable for TTR (0.69), cTn-I (0.60), and LVEF (0.64). However, an inclusive model that used all 3 factors rendered the greatest power (0.77). The 4-year ROC analysis was selected a priori as ATTRwt OS was 4 years; reported 4-year AUC values were similar for 3- and 5-year analyses (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves assessing the value of survival predictors on 4-year mortality.

Transthyretin (TTR), cardiac troponin I (cTn-I), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and all three values combined were assessed as predictors of 4-year overall survival in untreated patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt; n = 101). AUC indicates area under the curve; and CI, confidence interval.

To further examine the association of TTR with OS, untreated patients were stratified by the lower normal limit of circulating TTR, 18 mg/dL (Figure 3). Patients with baseline TTR ≥ 18 mg/dL had a median survival time of 4.1 years (95% CI, 3.6 – 5.5 y) versus 2.8 years (95% CI, 1.4 – 4.0 y) in the group with TTR below the threshold value (p = 0.03, HR = 2.3, 95% CI 1.2 – 4.3).

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) probability for patients with wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt).

Patients untreated for the duration of the follow-up (n = 101) were stratified by baseline transthyretin (TTR) threshold value of 18 mg/dL. Median OS for TTR ≥18 mg/dL was 4.1 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.6 – 5.5 y), and for TTR <18 mg/dL was 2.8 years (95% CI, 1.4 – 4.0 y).

Longitudinal analyses in ATTRwt

Cardiac and renal functional status markers at baseline were superior in the diflunisal-treated patients compared to those not taking drug. However, median TTR concentrations in both groups at baseline were similar (24 vs. 23 mg/dL, p = 0.466).

At 1-year evaluations of untreated and treated patients, values for two of three OS predictors, TTR and cTn-I, were significantly worse in the untreated group by a between-group analysis of median values (Table 3). Moreover, differences between the groups were maintained for both markers: TTR (20 vs. 31 mg/dL, p < 0.001) and cTn-I (0.126 vs. 0.064 ng/mL, p = 0.003) at 2-year follow-up. Within the untreated and treated patient groups, TTR, cTn-I and LVEF were assessed over the interval from baseline to 2-year follow-up and differences were noted for TTR and cTn-I (Figure 4; Supplemental Figure 2). In the untreated group, cTn-I significantly increased when measured longitudinally from baseline to 2-year evaluation (p = 0.006); there were also significant increases incrementally from baseline to1-year (p = 0.022), as well as 1-year to 2-year (p = 0.041) evaluations. In contrast, the diflunisal-treated group featured substantially increased TTR at 1-year evaluation compared to baseline (p = 0.001), which persisted through 2-year follow-up; these results paralleled stable levels of cTn-I at 1-year (p = 0.266) and 2-year follow-ups (p = 0.583).

Table 3.

Values of variables associated with survival at 1-year follow-up evaluations in untreated vs. diflunisal-treated ATTRwt patients

| Variable, median (range) | Untreated (n = 23) | Diflunisal-treated (n = 12) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| TTR (mg/dL) | 22 (12 – 29) | 30 (25 – 43) | < 0.001 |

| cTn-I (ng/mL) | 0.096 (0.021 – 0.376) | 0.058 (0.006 – 0.328) | 0.008 |

ATTRwt indicates wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis; TTR, transthyretin; and, cTn-I, cardiac troponin I

Figure 4. Change in transthyretin (TTR) and cardiac troponin (cTn-I) during 2-year follow-up in untreated and diflunisal-treated ATTRwt patients.

Tukey box-plots describe TTR and cTn-I values in untreated (A, B) and diflunisal-treated (C, D) groups at each visit including baseline, 1-year, and 2-year. P-values describing significant changes are shown above each graph.

Discussion

This is the first report to detail the results of a cross-sectional and longitudinal study of serum TTR concentrations, and analysis of TTR as a risk predictor in a large series of patients with biopsy-proven ATTRwt cardiac amyloidosis. Serum TTR was examined along with 14 other serologic measures and echocardiographic parameters to ascertain associations with survival; in addition, TTR concentrations at 1-year and 2-year follow-up evaluations were compared in diflunisal-treated and untreated ATTRwt patients. Major aspects of this study include: 1) confirmation that serum TTR concentrations in ATTRwt at diagnosis are near the lower limit of normal range, 2) establishment of serum TTR as a significant prognostic determinant in ATTRwt, 3) presentation of an inclusive model for predicting outcome using TTR, cTn-I, and LVEF, and 4) demonstration that diflunisal treatment coincided with significant increases in serum TTR concentration, and was associated with improving cardiac status during 2-year follow-up.

Key findings and clinical implications

Serum TTR concentrations in patients with ATTRwt were in the lower, normal range and comparable to matched, healthy controls; this finding that was in agreement with a previous report in a smaller series.8 Importantly, in this first study of TTR as a mortality indicator and predictor of outcome in ATTRwt amyloid disease, our data showed a significant association between lower levels of TTR and shorter survival, as well as a correlation to worsening cardiac disease, suggesting that TTR concentration is an indicator of disease progression and outcome in ATTRwt. We provide evidence that, despite biological associations with age, race, sex, nutritional status and inflammatory state, TTR has utility as a metric in ATTRwt and together with current cardiac function status markers can provide sensitive and specific monitoring of disease progression, response to treatment, and disease risk assessment. Although in this study, TTR correlated with CRP, sedimentation rate and albumin, all markers of inflammation, no significant multicollinearity was observed between TTR and any markers of inflammation or nutrition; any relationship of TTR to these factors had no effect on the Cox analysis. As quantification of TTR (frequently referred to as prealbumin testing) is routinely performed and commonly available in most clinical laboratories, measurement of this serum protein could readily be included in patient evaluation. Our findings and the availability of testing suggest that serum TTR concentration is a plausible metric of progression and outcome in ATTRwt disease.

More specifically, a serum TTR concentration of 18 mg/dL likely has potential utility as a threshold value in risk predictions. In the stratification of untreated patients at baseline using the 18 mg/dL threshold, we found that lower TTR was associated with poorer survival, as well as significantly higher BNP (p = 0.038). Moreover, in the follow-up analyses, patients exhibited worsening cardiac status temporally concomitant with declining TTR values that were lower than those who had been treated. While the untreated follow-up group represented patients who were more ill and unable to tolerate the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), diflunisal, it is important to note that progression of disease was only observed in the untreated group; in contrast, cardiac status remained stable in the treated group. Since diflunisal treatment coincided with both higher TTR and stabilized cardiac function, we ruled out drug effect in the survival analyses by limiting the group to patients that had never received TTR-stabilizing treatment. Small group numbers precluded statistical adjustment to eliminate data skewing for baseline health-status confounders; however, our conclusions were supported in a sub-analysis pairing of treated/untreated patients matched for baseline TTR, age, BMI, uric acid, and cTn-I (within 4 mg/dL, 5.1 y, 4 kg/m2, 2.1 mg/dL, and 0.06 ng/mL, respectively), and with normal CRP. Results showed declining TTR values and worsening disease characteristics in the untreated group while the treated patients exhibited increasing TTR and corresponding declining cardiac status markers (Supplemental Table 2). Despite small follow-up group numbers, our results indicate that TTR has prognostic utility and suggest that lowered TTR concentration corresponds to progression of cardiac amyloidosis.

The longitudinal data provide evidence that diflunisal treatment corresponded to increasing TTR concentration. Furthermore, OS was observed to increase in the total cohort including diflunisal-treated patients (n = 113; OS 4.7 vs. 4.1 y); these results suggest that patients receiving the TTR-stabilizing drug, albeit a small number (12 vs. 101) compared to the untreated group, may have extended survival. Of note, cardiac biomarkers were lower in diflunisal-treated patients reflecting a lower end-organ amyloid burden. Based on the TTR tetramer stabilizing effect of diflunisal predicted by in vitro experiments,25 the observed TTR increase with diflunisal treatment likely signals effective TTR stabilization and protection from renal clearance. Molecular stabilization of TTR by diflunisal has been shown to halt or slow neurologic disease progression in patients with ATTRm;26 however, the effect of diflunisal in ATTRwt has yet to be studied systematically. Undetermined are whether total TTR concentration or tetramer stabilization at presentation is specifically linked to better prognosis, or whether increases in TTR concentration and/or initially higher TTR levels at disease onset are beneficial.

Prior studies

The present investigation is an extension of our previously reported prospective, observational cohort study which documented the natural history of ATTRwt in a large series and identified BNP, RWT, LVEF and uric acid as factors associated with survival.15 While there was overlap in the patient groups used in the present and previous studies, the initial report by Connors et al. did not include TTR in the evaluation of serologic parameters in the ATTRwt series collected between 1994 – 2014, while the current study was restricted to patients with serum samples available for TTR quantification and evaluated from 2009 – 2016. In this recent analysis, multivariate testing identified reduced TTR and LVEF, and increased cTn-I as factors associated with worsening prognosis. These data add the predictive value of TTR to previous findings showing the prognostic value of cardiac measures. We consistently identified LVEF as a risk predictor, though our prior study found elevated BNP to be an indicator of reduced survival while the current analysis identified cTn-I as more significantly associated with outcome. It is not surprising that only one cardiac biomarker was present in each reported Cox model; this likely results from statistical overlap or may be due to the large range of BNP values represented in the present study which may obscure recognition of a survival association. Of note, atrial fibrillation was the most frequent arrhythmia in this study, as established previously.15

Grogan and colleagues from the Mayo Clinic proposed a staging system for ATTRwt based on cardiac troponin T (cTn-T) and N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) measurements,19 two related cardiac biomarkers not routinely measured at our center during the study period. These parameters were selected based on a similar Cox model analysis, in which age, LVEF, NT-proBNP and cTn-T were identified as multivariate risk factors for ATTRwt. Differences among the reports may stem from the list of tested variables; while our analyses did not include cTn-T and NT-proBNP, the study by Grogan et al. did not assess TTR and cTn-I. Nonetheless, the similarities in results between our two studies can be seen, in part, as external validation. In the Transthyretin Amyloid Outcomes Survey (THAOS),29 BNP and cTn-I were significantly elevated, while high cTn-T was associated with decreased survival in a report by Pinney et al.30 Most recently, a study by Arvanitis and colleagues employed a similar analysis of potential serological factors for early identification of patients with ATTRm V122I.31 Markers tested included TTR, RBP4, and indicators of cardiac damage, with RBP4 associating with ATTRm V122I disease expression. The association of TTR and RBP4, previous findings of lowered TTR levels in ATTRm, and the results of the current and most recent reports, all suggest that a deeper understanding of the relationship of serum TTR and RBP4 levels in ATTR-related cardiac diseases is warranted.

Importantly, several biomarkers of myocardial damage have been consistently identified as disease-associated prognostic risk factors by our group and others. Since the current study was the only one to consider TTR concentration, further investigation is necessary to confirm the utility of TTR as a specific marker of ATTRwt. Additionally, a combination of TTR and certain cardiac function measures may yield the most accurate survival prediction model in ATTRwt cardiac amyloidosis. Yet to be established, potentially through multi-center collaboration, is the combination of determinants that yield the greatest value as disease-specific indicators, and accuracy as predictors of outcome in ATTRwt.

Study limitations

Several limitations of our study should be considered. The examination of a relatively small cohort of patients is a limitation as small group numbers typically yield low-powered studies; however, this is the first report demonstrating the value of TTR, a serum protein routinely tested in clinical laboratories, as a potential ATTRwt disease marker. In addition, data from the survival analyses presented high levels of significance. Although a staging system has not been proposed, we anticipate the ever-expanding series of patients with ATTRwt evaluated at our center will confirm the importance of TTR concentration and provide a validation group for model testing in the future. Additionally, our study did not include echocardiographic strain, cardiac MRI, nuclear imaging data, and NT-proBNP measurements currently considered to be important in monitoring patients with ATTRwt cardiac amyloid disease.2,23 Many of the aforementioned metrics were unavailable on patients included in this series due to the retrospective nature of the study; furthermore, the small number of patients with data for some measures precluded inclusion in our analysis. Lastly, the biochemical nature of the TTR (tetramer, monomer, oligomer) that is quantified by antibody recognition in the immunoturbidometric assay is unknown. Whether a continuous decrease in specific amyloid-related or total circulating levels of TTR occurs during ATTRwt disease progression is yet to be determined; further studies may help to elucidate the mechanistic contributions of TTR gene expression, serum concentration, and fibril deposition in this disease.

Conclusions

In this first report that identifies TTR concentration as an independent predictor of OS in ATTRwt, we present an inclusive model combining 3 factors (TTR, cTn-I, LVEF) with high prognostic accuracy. Moreover, patients with TTR in the normal range (≥18 mg/dL) exhibited significantly better OS (4.1 years) compared to those with low TTR (<18 mg/dL, OS 2.8 years), suggesting the utility of 18 mg/dL as a threshold value in risk assessment. Further, we provide preliminary evidence that treatment with the TTR stabilizer, diflunisal, results in increased TTR concentration and stabilized cTn-I and LVEF over a two-year period, indicating a delay in progression of ATTRwt symptoms. In contrast, untreated patients exhibited persistently low TTR concentrations corresponding to worsening cardiac disease as represented by increasing cTn-I. These data suggest that TTR serum concentration at presentation predicts survival in patients with ATTRwt while serial TTR measurements provide an indication of disease progression.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Perspective.

What is new?

This report demonstrates that lowered serum TTR is a risk factor associated with marked cardiac impairment, worsening disease characteristics, and decreased survival in patients with ATTRwt.

We present a combined model of TTR, cardiac troponin (cTn-I), and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) as most predictive of 4-year survival.

What are the clinical implications?

The clinical evaluation of serum TTR levels, particularly in assessing concentrations outside the normal range, appears to be important as an individual metric, as well as in combination with other indicators of cardiac functional status.

Stratification of patients using a threshold serum TTR concentration of 18 mg/dL may have prognostic value and longitudinal measurement of the serum protein could potentially inform interpretation of disease course modification by diflunisal or future therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Sumeet Pawar, MD and Gloria Chan, MS for their assistance in data collection.

Sources of Funding

This research was supported by NIH R01AG031804 and NIH 2R56AG031804-06A1, and the Boston University School of Medicine Young Family Amyloid Research Fund.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Merlini G, Westermark P. The systemic amyloidoses: clearer understanding of the molecular mechanisms offers hope for more effective therapies. J Intern Med. 2004;255:159–178. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gertz MA, Dispenzieri A, Sher T. Pathophysiology and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:91–102. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rapezzi C, Merlini G, Quarta CC, Riva L, Longhi S, Leone O, Salvi F, Ciliberti P, Pastorelli F, Biagini E, Coccolo F, Cooke RMT, Bacchi-Reggiani L, Sangiorgi D, Ferlini A, Cavo M, Zamagni E, Fonte ML, Palladini G, Salinaro F, Musca F, Obici L, Branzi A, Perlini S. Systemic cardiac amyloidoses: disease profiles and clinical courses of the 3 main types. Circulation. 2009;120:1203–12. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Westermark P, Sletten K, Johansson B, Cornwell GG. Fibril in senile systemic amyloidosis is derived from normal transthyretin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2843–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mita S, Maeda S, Shimada K, Araki S. Analyses of prealbumin mRNAs in individuals with familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. J Biochem. 1986;100:1215–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a121826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rostom AA, Sunde M, Richardson SJ, Schreiber G, Jarvis S, Bateman R, Dobson CM, Robinson CV. Dissection of multi-protein complexes using mass spectrometry: subunit interactions in transthyretin and retinol-binding protein complexes. Proteins. 1998;(Suppl 2):3–11. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(1998)33:2+<3::aid-prot2>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie R. In: Serum Proteins in Clinical Medicine. Ritchie R, editor. Vol. 1. AACC; 1996. pp. 9.01–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buxbaum J, Koziol J, Connors LH. Serum transthyretin levels in senile systemic amyloidosis: effects of age, gender and ethnicity. Amyloid. 2008;15:255–261. doi: 10.1080/13506120802525285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson AM, Merlini G, Sheldon J, Ichihara K, Johnson AM. Clinical indications for plasma protein assays: transthyretin (prealbumin) in inflammation and malnutrition. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2007;45:419–426. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2007.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oppenheimer JH, Surks MI, Bernstein G, Smith JC. Metabolism of Iodine-131-Labeled Thyroxine-Binding Prealbumin in Man. Science (80-) 1965;149:748–50. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3685.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buxbaum J, Anan I, Suhr O. Serum transthyretin levels in Swedish TTR V30M carriers. Amyloid. 2010;17:83–85. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2010.483118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skinner M, Connors LH, Rubinow A, Libbey C, Sipe JD, Cohen AS. Lowered prealbumin levels in patients with familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) and their non-affected but at risk relatives. Am J Med Sci. 1985;289:17–21. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198501000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connors LH, Gertz MA, Skinner M, Cohen AS. Nephelometric measurement of human serum prealbumin and correlation with acute-phase proteins CRP and SAA: results in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Lab Clin Med. 1984;104:538–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng B, Connors LH, Davidoff R, Skinner M, Falk RH. Senile systemic amyloidosis presenting with heart failure: a comparison with light chain-associated amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1425–1429. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Connors LH, Sam F, Skinner M, Salinaro F, Sun F, Ruberg FL, Berk JL, Seldin DC. Heart failure resulting from age-related cardiac amyloid disease associated with wild-type transthyretin: a prospective, observational cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133:282–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawyer DB, Skinner M. Cardiac amyloidosis: shifting our impressions to hopeful. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2006;3:64–71. doi: 10.1007/s11897-006-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falk RH. Senile systemic amyloidosis: are regional differences real or do they reflect different diagnostic suspicion and use of techniques? Amyloid. 2012;19:68–70. doi: 10.3109/13506129.2012.674074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu PP, Smyth D. Wild-Type Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy: A Missed Cause of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction With Evolving Treatment Implications. Circulation. 2016;133:245–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grogan M, Scott CG, Kyle RA, Zeldenrust SR, Gertz MA, Lin G, Klarich KW, Miller WL, Maleszewski JJ, Dispenzieri A. Natural History of Wild-Type Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis and Risk Stratification Using a Novel Staging System. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1014–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapezzi C, Lorenzini M, Longhi S, Milandri A, Gagliardi C, Bartolomei I, Salvi F, Maurer MS. Cardiac amyloidosis: the great pretender. Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20:117–24. doi: 10.1007/s10741-015-9480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quarta CC, Solomon SD, Uraizee I, Kruger J, Longhi S, Ferlito M, Gagliardi C, Milandri A, Rapezzi C, Falk RH. Left ventricular structure and function in transthyretin-related versus light-chain cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation. 2014;129:1840–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dharmarajan K, Maurer MS. Transthyretin cardiac amyloidoses in older North Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:765–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03868.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maurer MS. Noninvasive identification of ATTRwt cardiac amyloid: the re-emergence of nuclear cardiology. Am J Med. 2015;128:1275–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gertz MA, Benson MD, Dyck PJ, Grogan M, Coelho T, Cruz M, Berk JL, Plante-Bordeneuve V, Schmidt HHJ, Merlini G. Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy of Transthyretin Amyloidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2451–2466. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adamski-Werner SL, Palaninathan SK, Sacchettini JC, Kelly JW. Diflunisal analogues stabilize the native state of transthyretin. Potent inhibition of amyloidogenesis. J Med Chem. 2004;47:355–74. doi: 10.1021/jm030347n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, Sekijima Y, Zeldenrust SR, Yamashita T, Heneghan MA, Gorevic PD, Litchy WJ, Wiesman JF, Nordh E, Corato M, Lozza A, Cortese A, Robinson-Papp J, Colton T, Rybin DV, Bisbee AB, Ando Y, Ikeda S, Seldin DC, Merlini G, Skinner M, Kelly JW, Dyck PJ. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2013;310:2658–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.283815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bulawa CE, Connelly S, Devit M, Wang L, Weigel C, Fleming JA, Packman J, Powers ET, Wiseman RL, Foss TR, Wilson IA, Kelly JW, Labaudinière R. Tafamidis, a potent and selective transthyretin kinetic stabilizer that inhibits the amyloid cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9629–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121005109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56:337–44. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coelho T, Maurer MS, Suhr OB. THAOS – The Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey: initial report on clinical manifestations in patients with hereditary and wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:63–76. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.754348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pinney JH, Whelan CJ, Petrie A, Dungu J, Banypersad SM, Sattianayagam P, Wechalekar A, Gibbs SDJ, Venner CP, Wassef N, McCarthy CA, Gilbertson JA, Rowczenio D, Hawkins PN, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ. Senile systemic amyloidosis: clinical features at presentation and outcome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013:2. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arvanitis M, Koch CM, Chan GG, Torres-Arancivia C, LaValley MP, Jacobson DR, Berk JL, Connors LH, Ruberg FL. Identification of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis Using Serum Retinol-Binding Protein 4 and a Clinical Prediction Model. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:305. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.