Abstract

Highly active antiretroviral therapy is well-established in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients. Nonadherence with therapy regimens often leads to the occurrence of opportunistic infections that further complicate treatment and challenge the treating physician. We report a young HIV-positive patient who suffered from progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy caused by the human John Cunningham virus and showed objective clinical improvement after adding mirtazapine to the treatment regimen, an observation that is supported by the emerging literature.

Keywords: Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), mirtazapine, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART)

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the human John Cunningham (JC) virus. JC virus is usually identified in immunosuppressed patients (e.g., patients with human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]). Previous case reports have claimed a favorable outcome by adding the serotonergic 5-hydroxytriptamine2A (5HT2A) receptor antagonist mirtazapine to the highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) of HIV-positive patients with PML, with improvement or stabilization of symptoms in 41- to 52-year-old patients with or without changes in the corresponding images.1,2 We questioned if adding mirtazapine to HAART in a young patient would have similar positive results. We report a 20-year-old HIV-positive patient who showed progressive neurocognitive decline due to PML. The patient had been nonadherent with HIV treatment for several years, so HAART was reinitiated and mirtazapine was added to the patient’s therapy regimen. The patient showed significant, quantifiable neurocognitive improvement after adding mirtazapine to the HAART therapy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated improvement in the subcortical white matter, an area that is commonly involved in PML. The results fall in line with in-vitro study results and the emerging literature claiming the benefit of adding mirtazapine to HAART, and illustrate how the combination of these therapies can have a synergistic effect. This case further illustrates that the age of the patient might positively impact clinical outcome, possibly due to different age-related brain plasticity.3

CASE REPORT

A 20-year-old Hispanic woman presented to the emergency department reporting suprapubic pain and was admitted to the United States/Mexico border hospital for treatment of a urinary tract infection. Review of her past medical history revealed that she had been diagnosed with HIV at the age of 11 and AIDS at the age of 16.

Throughout her hospital stay, the patient appeared confused and increasingly anxious. A psychiatric consultation found her to be disorientated to date, place, and location, along with poor concentration, executive function, insight, and judgment. Risperidone 0.5mg was prescribed to treat symptoms of delirium.

The patient had been nonadherent with HIV treatment for several years and was at an increased risk for opportunistic infections with a CD4 count of less than 50 cells/mm3 at the time. Neurosyphilis, HIV-related opportunistic infections, and underlying cognitive disorders were considered in narrowing the diagnosis. To further assess the status of the patient, the infectious disease department was consulted, and a physical exam revealed oral candidiasis and a new left upper-extremity (LUE) weakness.

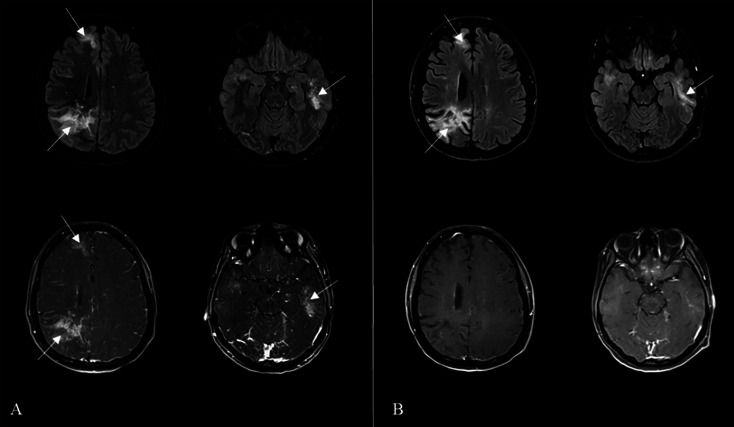

MRI of the brain demonstrated abnormal hyperintensities and hyperenhancement on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging. After the exclusion of differentials, the treatment team diagnosed the patient with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1:

(A) Initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain axial in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) (top row) and corresponding contrast enhanced T1-weighted images (bottom row) show multifocal, bilateral and asymmetric areas of hyperintensities and enhancement of the subcortical white matter of the right frontal, right parietal and left temporal lobes (arrows). (B) Follow-up MRI after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) and mirtazapine demonstrates near resolution of preexisting findings and interval development of multifocal encephalomalacia and supratentorial volume loss (arrows)

After two weeks of hospitalization, the patient remained disoriented to date, year, place, and location. In addition, she had significant motor retardation, inability to use full sentences, lack of insight, and poor abstraction. Due to the severity of the diagnosis and with recovery being unlikely, hospice and home care options were discussed with the family, and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

A month later, the patient presented for follow-up at our outpatient clinic. She had improved, had no recollection of her hospital admission, and reported reintroduction of HAART therapy at a local treatment center. The patient took the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a screening instrument for cognitive dysfunction, and received 16/30 points, suggesting cognitive impairment. A score of 26 and above is considered normal.

The patient continued her follow-up appointments with the psychiatric clinic. She expressed symptoms of depressed mood, poor sleep, decreased energy and appetite, and a persistent LUE weakness. Two months after the reintroduction of HAART, the serotonergic 5HT2A receptor antagonist mirtazapine 15mg was added to the patient’s therapy regimen as an antidepressant and as empirical treatment for PML. Mirtazapine targets the 5HT2A receptor, resulting not only in antidepressant properties but also in the medication’s ability to positively impact treatment of PML, likely due to targeting the same receptor that mediates the JC virus infection of the central nervous system (CNS).

Over the following seven months, the patient remained adherent with HAART and mirtazapine, and showed improvement in LUE weakness and quantifiable progress in her cognitive function (MoCA 22/30 [previously 16/30]). Corresponding follow-up MRIs of the brain demonstrated near resolution of the pre-existing findings (Figure 1B). The patient was able to perform daily tasks, played an active role in taking care of her child, and enjoyed writing and listening to music.

DISCUSSION

PML is a JC virus-mediated, opportunistic infection of the CNS that predominantly targets oligodendrocytes, and is associated with HIV infection in 55 to 85 percent of all PML cases.1 The lysis of oligodendrocytes, which are the myelin-producing cells of the CNS, results in subsequent mono- and/or multifocal demyelination of the white matter, which is the macroscopic and microscopic hallmark of PML, and atrophy of affected structures.4,5 The heterogeneous involvement of the white matter leads to a wide range of clinical presentations, with behavioral and cognitive impairment seen in one-third to one-half of the affected patients.4 Before the introduction of HAART, PML in HIV-positive patients had an associated one-year mortality of nearly 100 percent; however, mortality drops to 40 percent if treatment is initiated with the onset of PML.1

In-vitro studies have shown that JCV infection of oligodendrocytes is serotonin 5HT2A receptor-dependent and researchers have postulated that 5HT2A antagonists like mirtazapine might be beneficial in the treatment of PML by preventing the spread of the virus.6

Our case supports emerging literature that reports clinical improvement attributable to an empirical off-label use of mirtazapine in the treatment of HIV-positive patients with PML. Comparable beneficial effects of mirtazapine have been reported in HIV-negative patients with PML who are under immunosuppressive treatment for dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, or polycythemia vera as underlying diseases.7–9 Our case not only highlights the significance of immune reconstitution in both HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients with PML, but also the possible benefit of adding mirtazapine to their treatment plan.

Our case also underlines the importance of HAART in the treatment of HIV and illustrates the synergic effect of combining HAART with mirtazapine, which can lead to quantifiable clinical improvement and interval resolution of MRI findings even if the symptoms are severe. Our patient was younger than cases reported in the literature and showed marked clinical improvement, which was visible in MRI scans, within a few months. This suggests that the plasticity of the brain in a young adult might impact the course of the disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cettomai D, McArthur JC. Mirtazapine use in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(2):255–258. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanzafame M, Ferrari S, Lattuada E, et al. Mirtazapine in an HIV-1 infected patient with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Infez Med. 2009;17(1):35–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahncke HW, Bronstone A, Merzenich MM. Brain plasticity and functional losses in the aged: scientific bases for a novel intervention. Prog Brain Res. 2006;157:81–109. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)57006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berger JR, Aksamit AJ, Clifford DB, et al. PML diagnostic criteria: consensus statement from the AAN Neuroinfectious Disease Section. Neurology. 2013;80(15):1430–1438. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828c2fa1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark AS, Atlas SW. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with AIDS: appearance on MR images. Radiology. 1989;173(2):517–520. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.2.2798883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elphick GF, Querbes W, Jordan JA, et al. The human polyomavirus, JCV, uses serotonin receptors to infect cells. Science. 2004;306(5700):1380–1383. doi: 10.1126/science.1103492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vulliemoz S, Lurati-Ruiz F, Borruat FX, et al. Favourable outcome of progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in two patients with dermatomyositis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(9):1079–1082. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.092353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owczarczyk K, Hilker R, Brunn A, et al. Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in a patient with sarcoidosis—successful treatment with cidofovir and mirtazapine. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;2007;46:888–890. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem049. England. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verma S, Cikurel K, Koralnik IJ, et al. Mirtazapine in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with polycythemia vera. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(5):709–711. doi: 10.1086/520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]