Abstract

Background

While there are well-accepted standards for the diagnosis of arrested active-phase labor, the definition of a “failed” induction of labor remains less certain. One approach to diagnosing a failed induction is based on the duration of the latent phase. However, a standard for the minimum duration that the latent phase of a labor induction should continue, absent acute maternal or fetal indications for cesarean delivery, remains lacking.

Objective

The objective of this study was to determine the frequency of adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes as a function of the duration of the latent phase among nulliparous women undergoing labor induction.

Methods

This study is based on data from an obstetric cohort of women delivering at 25 U.S. hospitals from 2008–2011. Nulliparous women who had a term singleton gestation in the cephalic presentation were eligible for this analysis if they underwent a labor induction. Consistent with prior studies, the latent phase was determined to begin once cervical ripening had ended, oxytocin was initiated and rupture of membranes (ROM) had occurred, and was determined to end once 5 cm dilation was achieved. The frequencies of cesarean delivery, as well as of adverse maternal (e.g., cesarean delivery, postpartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionitis) and perinatal outcomes (e.g., a composite frequency of either seizures, sepsis, bone or nerve injury, encephalopathy, or death), were compared as a function of the duration of the latent phase (analyzed with time both as a continuous measure and categorized in 3-hour increments).

Results

A total of 10,677 women were available for analysis. In the vast majority (96.4%) of women, the active phase had been reached by 15 hours. The longer the duration of a woman’s latent phase, the greater her chance of ultimately undergoing a cesarean delivery (P<0.001, for time both as a continuous and categorical independent variable), although more than forty percent of women whose latent phase lasted for 18 or more hours still had a vaginal delivery. Several maternal morbidities, such as postpartum hemorrhage (P < 0.001) and chorioamnionitis (P < 0.001), increased in frequency as the length of latent phase increased. Conversely, the frequencies of most adverse perinatal outcomes were statistically stable over time.

Conclusion

The large majority of women undergoing labor induction will have entered the active phase by 15 hours after oxytocin has started and rupture of membranes has occurred. Maternal adverse outcomes become statistically more frequent with greater time in the latent phase, although the absolute increase in frequency is relatively small. These data suggest that cesarean delivery should not be undertaken during the latent phase prior to at least 15 hours after oxytocin and rupture of membranes have occurred. The decision to continue labor beyond this point should be individualized, and may take into account factors such as other evidence of labor progress.

Keywords: labor induction, latent phase, outcomes

Induction of labor has become an increasingly utilized obstetric intervention. Over the last two decades, its use has more than doubled, and at present, approximately 1 in 4 pregnant women have their labor induced.1 One conundrum faced by clinicians who are caring for women undergoing labor induction is whether the benefits outweigh the risks of continuing labor when a woman remains in the latent phase for an extended period of time. When a cesarean delivery occurs in the latent phase, the indication is sometimes labeled a “failed induction”. However, there has not been consensus regarding the criterion for this indication, and as a result, the approach to obstetric management in the latent phase for women undergoing labor induction varies among providers and institutions.2

Rouse et al. formulated one approach to defining a failed induction.3 They defined the latent phase as beginning when both oxytocin had been initiated and rupture of membranes had occurred, and ending when either 4 cm dilation and 90 effacement or 5 cm dilation regardless of effacement was reached. Obstetric outcomes were then studied as a function of the length of the latent phase in induced labors. They concluded that the latent phase could be allowed to extend to at least 12 hours without excess obstetric morbidity. However, their study population was relatively small and from a single site, and they could not adequately assess durations of the latent phase longer than 12 hours. Three other studies have been performed that have approached the diagnosis of a failed induction from this perspective, and to varying degrees have had similar methodological limitations.4–6

Determining a standard and evidence-based criterion for a cesarean that is performed in the latent phase for the sole reason that the patient has not entered the active phase is important if unnecessary cesarean deliveries are to be minimized and inter-institutional comparisons of care are to be possible.7 Thus, the purpose of this analysis was to determine, among a large and geographically varied population of nulliparous women undergoing labor induction, the maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with the length of the latent phase of labor.

Methods

Between 2008 and 2011, investigators at of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units (MFMU) Network performed an observational study (i.e., the APEX study). In this study, patient characteristics, intrapartum events, and pregnancy outcomes were collected on all women of at least 23 0/7 weeks with a live fetus on admission and delivered on randomly selected days representing one-third of deliveries over a three-year period at 25 participating hospitals. Trained and certified research personnel abstracted all charts. All centers obtained institutional review board approval and a waiver of informed consent. Full details of the technique of data collection have been described previously.8

Women were considered eligible for this analysis if they were nulliparous, had a singleton, cephalic gestation at ≥ 37 weeks, and underwent labor induction. The duration of the latent phase was defined in a similar fashion to that first elaborated by Rouse et al. and subsequently used by others in their analyses of the latent phase during labor induction.3 Specifically, the latent phase of labor in the setting of induction was defined to begin once any cervical ripening had been completed (i.e., when it was no longer used), oxytocin had begun, and rupture of membranes (either spontaneously or artificially) had occurred. Latent phase labor was defined to end once at least 5 cm dilation had been reached (or if cesarean occurred before that dilation). Women were excluded from the primary analysis if any of the times needed to calculate the length of the latent phase (e.g., time at membrane rupture, time at oxytocin initiation, time at least 5 cm was reached) were not available in the chart and, correspondingly, the length of the latent phase could not be determined.

Patient outcomes, including the frequency of cesarean delivery, adverse maternal outcomes (clinically-diagnosed chorioamnionitis, postpartum hemorrhage, hysterectomy), and adverse neonatal outcomes were compared as a function of the duration of the latent phase. The primary adverse neonatal outcome was a composite that was defined to occur when a neonate had any of the following: seizures, culture-proven sepsis, bone or nerve injury, encephalopathy, or death. These analyses were performed with time expressed both as a continuous variable and also as a categorical variable in 3-hour increments.

Generalized linear models for binary outcome with log-link function were used to estimate relative risks with 95% confidence intervals for the association of latent phase duration (expressed as a continuous variable in hours) with obstetric outcomes. The Cochran-Armitage or Exact test9 for trend was used to assess whether the frequency of obstetric outcomes changed as a function of the duration of the latent phase in 3-hour increments. A relative risk for each 3-hour interval was estimated with the generalized linear model utilizing the midpoint of the time interval as the value for the independent variable in the equation. The proportion of cesareans that occurred in the latent phase, in the active phase, and in the second stage, with the primary indications of non-reassuring fetal status (which included non-reassuring fetal heart tracing, cord prolapse, or abruption) or dystocia, were calculated for each 3-hour time interval as well.

In order to assess the robustness of our findings, several sensitivity analyses were performed. In one sensitivity analysis, the results of the analysis were re-estimated after the number of missing time values was reduced. In this analysis, the latent phase starting time was assigned according to the time at rupture of membranes or oxytocin, when only one of those times was available. In further sensitivity analyses, generalized linear models with the log-link function, with time as a continuous independent variable, were re-run after adjusting for each of the following three factors: cervical ripening used (yes/no), elective induction (yes/no), or premature rupture of membranes (yes/no). Adjustment in these models included the main effect of the factor as well as the interaction of the factor with time. SAS software version 9.4 was used for the analyses. All tests were two sided and P < .05 was used to define statistical significance with no adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Results

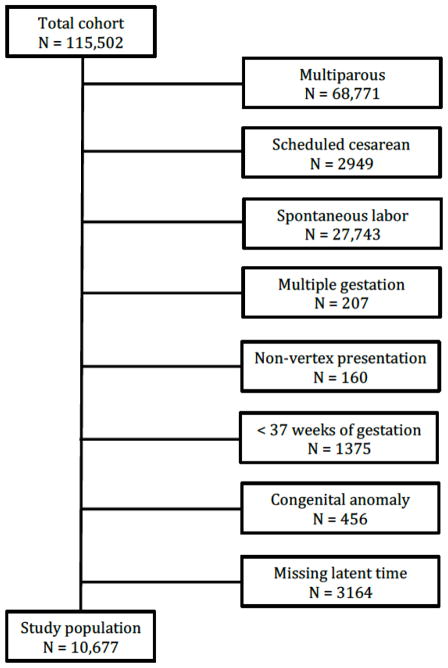

A total of 10,677 women met inclusion criteria and were available for analysis (Figure 1), 1725 (16.2%) of whom underwent induction for premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and 5582 (52.3%) of whom underwent cervical ripening (Table 1). For women who did not present with PROM, the median (inter-quartile range (IQR)) duration between initiation of oxytocin and rupture of membranes was 215 minutes (IQR 75–418 minutes) for women who underwent cervical ripening and 180 minutes (IQR 65–332 minutes) for women who did not undergo cervical ripening. The median duration from having had both oxytocin started and rupture of membranes (defined in this analysis as the start of the latent phase) to active labor (or cesarean delivery if active labor was not reached) was 262 minutes (IQR 141–435 minutes). By 6 hours almost two-thirds of women had progressed from the start of the latent phase to active labor, and in the vast majority (96.4%) of women, the active phase had been reached by 15 hours (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating composition of the study population of nulliparous women at term with non-anomalous vertex singleton gestations undergoing labor induction

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Characteristic | N = 10,677 |

|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 26.4±6.1 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32.2±6.7 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 39.8±1.3 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 5724 (53.6) |

| Black | 2153 (20.2) |

| Hispanic | 1665 (15.6) |

| Asian | 570 (5.3) |

| Other | 565 (5.3) |

| Reason for labor induction | |

| Maternal medical condition* | 2562 (24.0) |

| Late or post-term | 3004 (28.1) |

| Fetal status** | 1636 (15.3) |

| PROM | 1725 (16.2) |

| Elective | 1468 (13.8) |

| Other | 282 (2.6) |

| Cervical ripening | 5582 (52.3) |

| Epidural use | 10,038 (95.0) |

| Birth weight (g) | 3,369±477 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or N(%)

includes maternal co-morbidities, such as hypertensive disease and diabetes mellitus, that are indications for labor induction

includes fetal growth restriction, oligohydramnios, non-reassuring antepartum surveillance

PROM = premature rupture of membranes

Table 2.

Proportion of women no longer in the latent phase after the initiation of labor induction*

| Latent phase (hours) | N | % | Cumulative % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2.9 | 3523 | 33.0 | 33.0 |

| 3–5.9 | 3470 | 32.5 | 65.5 |

| 6–8.9 | 1997 | 18.7 | 84.2 |

| 9–11.9 | 921 | 8.6 | 92.8 |

| 12–14.9 | 380 | 3.6 | 96.4 |

| 15–17.9 | 192 | 1.8 | 98.2 |

| ≥18 | 194 | 1.8 | 100.0 |

Women at least 5 cm (or who had a cesarean within the given time interval) after cervical ripening had been completed, oxytocin had begun, and rupture of membranes (either spontaneously or artificially) had occurred.

The longer the duration of a woman’s latent phase, the greater her chance of ultimately undergoing a cesarean delivery (P < 0.001 for time both as a continuous and categorical independent variable, Table 3). Nevertheless, more than forty percent of women whose latent phase lasted for 18 or more hours delivered vaginally. The indications for cesarean, stratified by phase and stage of labor, are presented in Table 4. As is illustrated, the majority of the cesareans at any of the time intervals – and in particular at the earlier time intervals that were less than 15 hours – were not performed in the latent phase. Several maternal morbidities (i.e., chorioamnionitis, postpartum hemorrhage, and blood transfusion) also increased in frequency as the length of the latent phase increased.

Table 3.

Frequency of maternal outcomes stratified by duration of latent phase

| Latent Phase (hours) |

N | Cesarean N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Chorio- amnionitis N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

PPH N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

3rd/4th degree N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Blood transfusion N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

Hyster- ectomy N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time as a continuous variable (hours) | |||||||||||||

| 10,677 | 3608 (33.8) | 1.047 (1.043 – 1.052) | 1109 (10.4) | 1.071 (1.061 – 1.082) | 268 (2.6) | 1.068 (1.044 – 1.092) | 572 (5.4) | 0.985 (0.966 – 1.005) | 175 (1.6) | 1.074 (1.044 – 1.104) | 6 (0.06) | 1.144 (1.007 – 1.298) | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| Time as a categorical variable (3-hour increments) | |||||||||||||

| 0–2.9 | 3523 | 932 (26.5) | Referent | 241 (6.8) | Referent | 66 (1.9) | Referent | 182 (5.2) | Referent | 39 (1.1) | Referent | 2 (0.06) | Referent |

| 3–5.9 | 3470 | 1025 (29.5) | 1.15 (1.14–1.16) | 294 (8.5) | 1.23 (1.19–1.27) | 79 (2.4) | 1.22 (1.14–1.30) | 199 (5.7) | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 54 (1.6) | 1.24 (1.14–1.35) | 1 (0.03) | 1.50 (1.02–2.19) |

| 6–8.9 | 1997 | 787 (39.4) | 1.32 (1.29–1.35) | 251 (12.6) | 1.51 (1.43–1.60) | 51 (2.6) | 1.49 (1.30–1.70) | 119 (6.0) | 0.91 (0.81–1.03) | 36 (1.8) | 1.53 (1.30–1.81) | 0 | 2.24 (1.04–4.79) |

| 9–11.9 | 921 | 433 (47.0) | 1.52 (1.46–1.57) | 160 (17.4) | 1.86 (1.70–2.03) | 26 (2.9) | 1.81 (1.48–2.22) | 42 (4.6) | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 16 (1.7) | 1.90 (1.48–2.43) | 0 | 3.34 (1.07–10.5) |

| 12–14.9 | 380 | 207 (54.5) | 1.74 (1.66–1.83) | 84 (22.1) | 2.28 (2.03–2.56) | 23 (6.2) | 2.21 (1.69–2.89) | 13 (3.4) | 0.84 (0.66–1.06) | 13 (3.4) | 2.35 (1.69–3.27) | 2 (0.53) | 5.00 (1.09–23.0) |

| 15–17.9 | 192 | 115 (59.9) | 2.00 (1.88–2.13) | 47 (24.5) | 2.81 (2.43–3.24) | 11 (5.8) | 2.69 (1.92–3.77) | 10 (5.2) | 0.80 (0.60–1.07) | 7 (3.7) | 2.91 (1.92–4.40) | 0 | 7.48 (1.11–50.3) |

| ≥18 | 194 | 109 (56.2) | 2.30 (2.14–2.47) | 32 (16.5) | 3.45 (2.90–4.10) | 12 (6.3) | 3.28 (2.19–4.91) | 7 (3.6) | 0.76 (0.54–1.09) | 10 (5.2) | 3.60 (2.19–5.92) | 1 (0.52) | 11.2 (1.14–110.0) |

| * P value | ------ | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.252 | 0.138 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.035 | 0.039 |

PPH = postpartum hemorrhage

Cochran-Armitage or Exact trend test

Table 4.

Frequency of indications for cesarean delivery, stratified by phase and stage of labor

| Latent phase | Active phase | Second stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent phase, hours | NRFS | Dystocia | NRFS | Dystocia | NRFS | Dystocia |

| 0–2.9 (N=932) | 144 (15.5) | 41 (4.4) | 178 (19.1) | 369 (40.1) | 50 (5.4) | 148 (15.9) |

| 3–5.9 (N=1025) | 114 (11.1) | 144 (14.0) | 129 (12.6) | 385 (37.6) | 46 (4.5) | 206 (20.1) |

| 6–8.9 (N=787) | 77 (9.8) | 234 (29.7) | 74 (9.4) | 271 (34.4) | 19 (2.4) | 109 (13.9) |

| 9–11.9 (N=433) | 39 (9.0) | 139 (32.1) | 38 (8.8) | 151 (34.9) | 9 (2.1) | 57 (13.2) |

| 12–14.9 (N=207) | 25 (12.1) | 71 (34.3) | 16 (7.7) | 65 (31.4) | 4 (1.9) | 24 (11.6) |

| 15–17.9 (N=115) | 9 (7.8) | 55 (47.8) | 9 (7.8) | 31 (27.0) | 3 (2.6) | 8 (7.0) |

| ≥18 (N=109) | 9 (8.3) | 48 (44.0) | 5 (4.6) | 33 (30.3) | 2 (1.8) | 12 (11.0) |

Data presented as N (%)

NRFS = non-reassuring fetal status

Conversely, the frequency of most neonatal adverse outcomes did not differ as a function of time. Specifically, there was no statistical increase in the frequency of the primary neonatal adverse outcome, or of outcomes such as low Apgar score, acidemia, or shoulder dystocia. The frequency of NICU admission increased with duration of the latent phase (Table 5).

Table 5.

Frequency of neonatal outcomes stratified by duration of latent phase

| Latent Phase (hours) | N | 5 minute Apgar < 4 N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) | UA pH<7.0† N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) | Shoulder dystocia N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) | ANC N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) | NICU N(%) |

Relative risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–2.9 | 3523 | 6 (0.2) | Referent | 15 (1.2) | Referent | 81 (2.3) | Referent | 38 (1.1) | Referent | 299 (8.5) | Referent |

| 3–5.9 | 3470 | 8 (0.2) | 1.23 (0.99–1.54) | 10 (0.8) | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | 86 (2.5) | 0.96 (0.87–1.05) | 37 (1.1) | 1.10 (0.98–1.23) | 302 (8.7) | 1.10 (1.06–1.15) |

| 6–8.9 | 1997 | 5 (0.3) | 1.52 (0.97–2.38) | 9 (1.2) | 1.22 (0.86–1.75) | 46 (2.3) | 0.91 (0.76–1.10) | 20 (1.0) | 1.21 (0.97–1.52) | 199 (10.0) | 1.22 (1.13–1.31) |

| 9–11.9 | 921 | 4 (0.4) | 1.87 (0.96–3.67) | 3 (0.8) | 1.35 (0.80–2.31) | 16 (1.7) | 0.87 (0.66–1.15) | 16 (1.8) | 1.33 (0.95–1.87) | 98 (10.6) | 1.35 (1.20–1.51) |

| 12–14.9 | 380 | 0 | 2.31 (0.94–5.65) | 2 (1.1) | 1.50 (0.74–3.05) | 7 (1.9) | 0.83 (0.58–1.21) | 4 (1.1) | 1.47 (0.94–2.30) | 44 (11.6) | 1.49 (1.28–1.73) |

| 15–17.9 | 192 | 0 | 2.85 (0.93–8.72) | 2 (2.3) | 1.66 (0.68–4.03) | 4 (2.1) | 0.80 (0.50–1.26) | 8 (4.2) | 1.61 (0.92–2.83) | 29 (15.1) | 1.64 (1.36–1.98) |

| ≥18 | 194 | 2 (1.0) | 3.51 (0.92–13.44) | 3 (3.3) | 1.83 (0.63–5.32) | 3 (1.6) | 0.76 (0.44–1.32) | 2 (1.0) | 1.78 (0.91–3.48) | 33 (17.0) | 1.81 (1.45–2.27) |

| * P value | ------ | 0.158 | 0.067 | 0.268 | 0.264 | 0.258 | 0.334 | 0.041 | 0.094 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

UA = umbilical artery; ANC = adverse neonatal composite (seizures, sepsis, bone or nerve injury, encephalopathy, death); NICU = neonatal intensive care unit admission

Cochran-Armitage or Exact trend test

Data are missing for 6,666 neonates

Lastly, for sensitivity analyses, we examined whether results differed after the number of missing values for latent phase duration were reduced (leaving only 746 latent phase durations missing), or after adjustment for whether cervical ripening had been used, the induction was undertaken without a medical indication (i.e., an elective induction), or PROM had occurred. In all sensitivity analyses, the associations between duration of the latent phase and outcomes remained similar to those of the primary analysis (data not shown).

Comment

This study has described several aspects of the latent phase in the setting of labor induction that may be helpful when considering recommendations regarding management of labor. First, a very large majority of women (i.e., more than 96%) will enter the active phase within 15 hours of the completion of cervical ripening (if any is needed), the initiation of oxytocin, and rupture of membranes. The women who do are more likely than not to have a vaginal delivery and be free of maternal and perinatal morbidity. These patterns were extant regardless of whether the induction was without medical indication, was after PROM, or was after cervical ripening. Also, there is no one time at which complications suddenly arise, although there is an incremental increase in the frequency of several maternal complications, and of NICU admission, as time progresses.

These findings extend the findings of other investigators who have performed similar analyses.3–6 Studies such as those of Chelmow et al and Maghoba et al, for example, demonstrated that “prolonged” latent phases were associated with more frequent maternal and neonatal complications, although these studies neither were restricted to labor induction nor used a single consensus definition of “prolonged.”10,11 Rouse et al. performed the first study that used a similar approach to that of the present analysis in order to try to determine the association between duration of the latent phase and obstetric complications in the setting of labor induction.3 Their study included 509 women of mixed parity and demonstrated that “continued labor induction allowed some women to have vaginal deliveries”, that chorioamnionitis rose with longer times of the latent phase, and that major maternal and perinatal complications were uncommon. They did not, however, have sufficient sample size to compare more uncommon neonatal complications, such as umbilical artery pH < 7.0, according to latent phase duration or reliably estimate the outcomes after 12 hours or more of the latent phase.

Subsequent analyses by Simon et al (n = 397) and Rouse et al. (n = 1347) included more nulliparous women with latent phase durations greater than 12 hours and concluded that even after 12 hours in the latent phase, vaginal delivery occurred with reasonable frequency and complications remained uncommon.4,5 For example, in the analysis by Simon et al, 67% of women who had a latent phase of 12–18 hours after the completion of any cervical ripening, oxytocin initiation, and rupture of membranes had a vaginal delivery without a discernible increase in perinatal complications. In a recent analysis of data from 9763 nulliparous women in the Consortium of Safe Labor study, in which 6 cm was used to define the end of latent labor, admission to the NICU (but not mechanical ventilation or sepsis) was statistically more frequent (8.7% at 12 hours vs. 6.7% at 9 hours) once 12 hours of the latent phase had been reached.6 While that study used 6 cm to define the end of the latent phase, the results are similar to our study (in which 5 cm was used as the terminal dilation for the latent phase).

There are several strengths of this study, including the size of the population, the quality of the data (which were abstracted by trained research personnel from each chart), and the diversity of a nationwide cohort. Women were included with a variety of indications for labor induction and with differing needs for cervical ripening, and the associations observed remained present even after taking these factors into account. Conversely, factors such as maternal age or body mass index were not adjusted for, given that these may not be mere covariates but causally related to both exposure and outcome.12

Despite these strengths, its limitations should be acknowledged. Because of its observational nature, the associations observed cannot be known to imply causality. Even with good data quality and control processes, particular types of data (such as times for multiple events throughout labor) may be missing in the chart and thus not able to be abstracted. If this missingness is not random, but related systematically to the outcome and exposure, bias may be introduced. However, in a sensitivity analysis in which the number of missing times was reduced by more than 75%, the results remained unchanged. Also, these findings are for nulliparous women and cannot be generalized to parous women. Nevertheless, we believe nulliparous women are the population most in need of study, given their much greater chance of prolonged labor and cesarean delivery. Because this study was concerned with the length of the latent phase during induction, it provides no insight into the latent phase during spontaneous labor. Although this study occurred at many institutions, most were academic centers with training programs, and thus generalizability to community hospitals cannot be certain. Yet, it is not evident why the presence of associations between duration of a phase of labor and obstetric outcomes should differ based on community or academic setting. And, one could consider the many institutions and the lack of a single protocol for induction or labor management as a strength of the study, as these characteristics increase the applicability of the findings to other institutions, which similarly lack one single standard for all aspects of labor management. Other studies of labor standards, such as those from the Consortium of Safe Labor, also have benefited from analysis of labor management as it occurs in actual clinical settings and not after imposition of a standard study protocol.13 Nevertheless, we cannot know with certainty whether these findings are generalizable to all health care settings.

This study presents one, but certainly not the only approach, to assessing the extent to which the latent phase should continue, in the absence of acute indication for delivery, during labor induction. Other approaches, for example, include determination of inflection points on labor curves as well as categorizing abnormality based on population-level percentiles.13–16 This presently-applied approach, however, has several advantages, including that it standardizes the duration as a function of several aspects of management in order to establish a common “clock” and directly assesses the relationship between duration and obstetric outcome. Indeed, some investigators have stressed the importance of determining labor definitions and utility of different management approaches in the context of their maternal and neonatal outcomes.17,18 Regardless of the specific approach, a standard for the minimum duration of the latent phase that should be employed in the setting of labor induction is sorely needed. Obstetric providers are routinely faced with the question, for women who have not entered the active phase, of whether the benefits of allowing an induction to continue outweigh the risks. Lacking a standard, inter-patient and inter-institutional variability result. As our data demonstrate, even though cesarean for “dystocia” or “failed induction” was not frequent, it not only was cited as an indication but occurred at a variety of durations throughout the latent phase.

Converting these data into a discrete clinical recommendation is challenging given there is no single time interval at which the complications suddenly arise, at which the marginal increase in the frequency of complications dwarfs the marginal increase during antecedent intervals, or at which there is no longer a balance of benefit (such as avoidance of additional cesareans) with risk. However, given that the vast majority of women will progress to the active phase by 15 hours, that most women who do will progress to a vaginal delivery, and that relatively few will have adverse outcomes, we believe that our results are consistent with prior recommendations.3–5,7 Specifically, among women undergoing labor induction, when maternal and fetal maternal and fetal conditions permit, cesarean delivery should not be undertaken in the latent phase prior to at least 15 hours after rupture of membranes has occurred and oxytocin has been started. The decision to continue labor beyond this point should be individualized, and may take into account factors such as other evidence of labor progress.

The advantages of such an approach are illustrated by one study that demonstrated that introduction of a protocol that specified a minimum amount of time before a failed induction was diagnosed (in that case, 12 hours after ripening, oxytocin, and membrane rupture) was associated with a significantly lower frequency of cesarean and no greater frequency of adverse outcomes.19 And, based on our data, the public health ramifications of adherence to a standard definition for “failed induction” can be estimated. If induction were to be designated as “failed” if a woman continued to be in the latent phase at 15 as opposed to 6 hours after the initiation of oxytocin and rupture of membranes, approximately 70,000 additional cesarean deliveries could be avoided among the 400,000 nulliparous women who undergo induction in the United States every year.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [HD21410, HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34208, HD36801, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, HD40485, HD53097, HD53118] and the National Center for Research Resources [UL1 RR024989; 5UL1 RR025764]. Comments and views of the authors do not necessarily represent views of the NIH.

The authors thank Cynthia Milluzzi, R.N. and Joan Moss, R.N.C., M.S.N. for protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers; and Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D., Madeline M. Rice, Ph.D., Brian M. Mercer, M.D. and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D. for protocol development and oversight.

Appendix

In addition to the authors, other members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network are as follows:

Northwestern University, Chicago, IL – G. Mallett, M. Ramos-Brinson, A. Roy, L. Stein, P. Campbell, C. Collins, N. Jackson, M. Dinsmoor (NorthShore University HealthSystem), J. Senka (NorthShore University HealthSystem), K. Paychek (NorthShore University HealthSystem), A. Peaceman

Columbia University, New York, NY – M. Talucci, M. Zylfijaj, Z. Reid (Drexel U.), R. Leed (Drexel U.), J. Benson (Christiana H.), S. Forester (Christiana H.), C. Kitto (Christiana H.), S. Davis (St. Peter’s UH.), M. Falk (St. Peter’s UH.), C. Perez (St. Peter’s UH.)

University of Utah Health Sciences Center, Salt Lake City, UT – K. Hill, A. Sowles, J. Postma (LDS Hospital), S. Alexander (LDS Hospital), G. Andersen (LDS Hospital), V. Scott (McKay-Dee), V. Morby (McKay-Dee), K. Jolley (UVRMC), J. Miller (UVRMC), B. Berg (UVRMC)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC –K. Dorman, J. Mitchell, E. Kaluta, K. Clark (WakeMed), K. Spicer (WakeMed), S. Timlin (Rex), K. Wilson (Rex)

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX –L. Moseley, M. Santillan, J. Price, K. Buentipo, V. Bludau, T. Thomas, L. Fay, C. Melton, J. Kingsbery, R. Benezue

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA – H. Simhan, M. Bickus, D. Fischer, T. Kamon (deceased), D. DeAngelis

Case Western Reserve University-MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH – B. Mercer, C. Milluzzi, W. Dalton, T. Dotson, P. McDonald, C. Brezine, A. McGrail

The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH – C. Latimer, L. Guzzo (St. Ann’s), F. Johnson, L. Gerwig (St. Ann’s), S. Fyffe, D. Loux (St. Ann’s), S. Frantz, D. Cline, S. Wylie, J. Iams

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL – M. Wallace, A. Northen, J. Grant, C. Colquitt, D. Rouse, W. Andrews

University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, TX – J. Moss, A. Salazar, A. Acosta, G. Hankins

Wayne State University, Detroit, MI – N. Hauff, L. Palmer, P. Lockhart, D. Driscoll, L. Wynn, C. Sudz, D. Dengate, C. Girard, S. Field

Brown University, Providence, RI – P. Breault, F. Smith, N. Annunziata, D. Allard, J. Silva, M. Gamage, J. Hunt, J. Tillinghast, N. Corcoran, M. Jimenez

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston-Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX – F. Ortiz, P. Givens, B. Rech, C. Moran, M. Hutchinson, Z. Spears, C. Carreno, B. Heaps, G. Zamora

Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR – J. Seguin, M. Rincon, J. Snyder, C. Farrar, E. Lairson, C. Bonino, W. Smith (Kaiser Permanente), K. Beach (Kaiser Permanente), S. Van Dyke (Kaiser Permanente), S. Butcher (Kaiser Permanente)

The George Washington University Biostatistics Center, Washington, D.C. – E. Thom, M. Rice, Y. Zhao, P. McGee, V. Momirova, R. Palugod, B. Reamer, M. Larsen

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD – C. Spong, S. Tolivaisa

MFMU Network Steering Committee Chair (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC) – J. P. Van Dorsten, M.D.

Footnotes

No author has a conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64:1–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baños N, Migliorelli F, Posadas E, Ferreri J, Palacio M. Definition of Failed Induction of Labor and Its Predictive Factors: Two Unsolved Issues of an Everyday Clinical Situation. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2015 doi: 10.1159/000433429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouse DJ, Owen J, Hauth JC. Criteria for failed labor induction: prospective evaluation of a standardized protocol. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:671–7. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon CE, Grobman WA. When has an induction failed? Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:705–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000157437.10998.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rouse DJ, Weiner SJ, Bloom SL, Varner MW, Spong CY, Ramin SM, et al. Failed labor induction: toward an objective diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:267–72. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318207887a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawakita T, Reddy UM, Iqbal SN, et al. Duration of oxytocin and rupture of the membranes before diagnosing a failed induction of labor. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailit JL, Grobman WA, Rice MM, et al. Risk-adjusted models for adverse obstetric outcomes and variation in risk-adjusted outcomes across hospitals. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:446.e1–446.e30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agresti A. A Survey of Exact Inference for Contingency Tables. Stat Sci. 1992;7:131–77. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chelmow D, Kilpatrick SJ, Laros RK., Jr Maternal and neonatal outcomes after prolonged latent phase. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:486–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maghoma J, Buchmann EJ. Maternal and fetal risks associated with prolonged latent phase of labour. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:16–9. doi: 10.1080/01443610120101637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ananth CV, Schisterman EF. Confounding, causality, and confusion: the role of intermediate variables in interpreting observational studies in obstetrics. AJOG. 2017;217:167–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, Landy H, Branch DW, et al. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1281–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedman EA. The graphic analysis of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1954;68:1568–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(54)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman EA. Primigravid labor: a graphicostatistical analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:567–89. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02398-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J, Troendle J, Yancey MK. Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:824–8. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley GE, Munro S, Greyson D, et al. Diagnosing onset of labor: a systematic review of definitions in the research literature. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0857-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lavender T, Hart A, Smyth R. Effect of partogram use on outcomes for women in spontaneous labour at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;7:CD005461. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005461.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhinehart-Ventura J, Eppes C, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, et al. Evaluation of outcomes after implementation of an induction-of-labor protocol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211:301.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]