Abstract

Background

Over the past decade, collaboration between general practices in England to form new provider networks and large-scale organisations has been driven largely by grassroots action among GPs. However, it is now being increasingly advocated for by national policymakers. Expectations of what scaling up general practice in England will achieve are significant.

Aim

To review the evidence of the impact of new forms of large-scale general practice provider collaborations in England.

Design and setting

Systematic review.

Method

Embase, MEDLINE, Health Management Information Consortium, and Social Sciences Citation Index were searched for studies reporting the impact on clinical processes and outcomes, patient experience, workforce satisfaction, or costs of new forms of provider collaborations between general practices in England.

Results

A total of 1782 publications were screened. Five studies met the inclusion criteria and four examined the same general practice networks, limiting generalisability. Substantial financial investment was required to establish the networks and the associated interventions that were targeted at four clinical areas. Quality improvements were achieved through standardised processes, incentives at network level, information technology-enabled performance dashboards, and local network management. The fifth study of a large-scale multisite general practice organisation showed that it may be better placed to implement safety and quality processes than conventional practices. However, unintended consequences may arise, such as perceptions of disenfranchisement among staff and reductions in continuity of care.

Conclusion

Good-quality evidence of the impacts of scaling up general practice provider organisations in England is scarce. As more general practice collaborations emerge, evaluation of their impacts will be important to understand which work, in which settings, how, and why.

Keywords: general practice, health services, organisation and administration, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

New organisational forms of collaboration between general practices for the provision of care have emerged across England over the past decade.1,2 These include general practice networks, federations, super-partnerships, and multisite practice organisations. It has been argued that they are better placed than the traditional, smaller, independent business partnerships between a small number of GPs to strengthen the workforce, improve quality of care, extend services, and generate efficiencies.2–7 Although many of the earliest collaborations emerged through grassroots initiatives, building on existing local relationships, national policies are increasingly driving collaborations. This is with a view to creating much larger ‘accountable care’-type organisations, in which primary and secondary, and, in some cases, social care providers, collaborate to provide comprehensive care for defined populations, within a shared budget.6–8

Many of the expectations of what scaling up general practices will achieve appear logical, however, it is unclear what research evidence exists to support them. This article presents a systematic review of the evidence on the impact of new organisational forms of collaboration between general practices for the provision of care in England.

METHOD

This review contributed to a larger project led by the Nuffield Trust on large-scale general practice.9 The search strategy was developed with a health services research librarian to identify literature on the impact of collaboration between three or more general practices on clinical processes, clinical outcomes, patient experience, workforce satisfaction, and costs. The databases Embase, MEDLINE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), and Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) were searched for literature in English, initially between January 1996 and March 2016. The database search was re-run in January 2017 to capture any subsequent peer-reviewed literature. Additional academic and grey texts were identified by screening the references of relevant publications, seeking recommendations from experts in the fields of primary care and health services research, and by examining relevant websites, GP media reports, and policy documents. These are methods known to increase yields of relevant results in systematic reviews.10 The protocol was not registered.

The search strategy had initially aimed to capture evidence systematically from international and UK contexts. However, as a result of heterogeneity in the terminology used, as well as in the process and context of implementation of scaling up general practice, it became evident that, despite using several search strategies, such a wide systematic review was neither feasible nor likely to provide clearly transferable evidence. Therefore, the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied aimed to identify studies with greatest relevance to current developments in England and robust research methods. These criteria are outlined in Box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the systematic review.

Inclusion criteria

Study evaluates the impact of new forms of collaboration between three or more GP practices working collectively to provide routine clinical care in England, for example, general practice networks, federations, super-partnerships, or multisite practice organisations.2

Study reports on the impact of one or more of the following as a result of the collaboration: quality of care processes indicators, clinical outcomes, patient experience, workforce satisfaction, or costs.

Exclusion criteria

Descriptive case studies without primary data, clear methodology, and/or with only self-reported impacts.

Studies including new forms of collaboration, but the evaluation of the collaboration’s impact is not a focus of the study and cannot therefore be identified from the rest of the initiative.

Studies of organisations only providing out-of-hours care.

All titles and abstracts identified were screened, with full publications being read by the same researcher if they appeared relevant. Publications were assessed using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If there was uncertainty over whether a study met inclusion or exclusion criteria, it was discussed until consensus was reached. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists were used to evaluate the quality of included studies.11

How this fits in

National policy increasingly advocates the development of large-scale provider collaborations between general practices, with expectations that they will be better placed than individual practices to strengthen the workforce, improve quality of care, extend services, and generate economies of scale. A systematic review was carried out to examine the impact of new forms of provider collaborations in England to understand what evidence exists to support these expectations. Limited evidence was found that met the inclusion criteria. Five studies point to potential improvements in quality of care through scaling up. Four of these were from the same general practice networks. There is a need for realistic expectations of what scaling up may achieve in England and cautious implementation alongside evaluation to understand better what is likely to work, for whom, and in which contexts.

Data were extracted on templates by two authors, with discussion to reach consensus, and narrative synthesis was used to present the findings.12

RESULTS

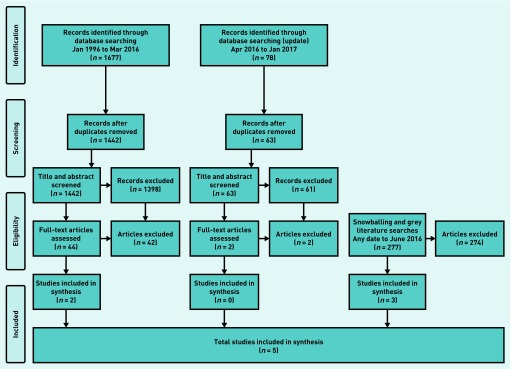

After the exclusion of duplicates, 1782 texts were screened. Literature that did not meet the inclusion criteria often described the development, rather than impact, of large-scale general practice collaborations;3–5,12 was of poor methodological quality;13–17 or it was not possible to disentangle the impact of the new collaboration from wider initiatives.18–22 Evidence from initiatives with similarities to the process of formation and/or objectives of scaled-up general practice provider collaborations in England including specialist clinical networks, integrated care initiatives, GP-led commissioning, and out-of-hours cooperatives, as well as evidence from other countries, did not meet the inclusion criteria. However, it helped inform the interpretation of the findings, assessment of the implications for policy, and contributed to a wider review of the literature presented elsewhere.23 Only five studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of systematic review process.

Four studies examined networks of general practices in the same London borough of Tower Hamlets. These evaluations focused on quantitative assessments of the impact of intervention packages delivered by new networks of practices on quality of care processes and clinical outcomes. These were tracked over the period of implementation, and between 1 and 3 years afterwards. Performance was compared against averages in London and England. The studies provided some cost data, but no cost-effectiveness analysis (Table 1). All four studies had a moderate risk of bias based on CASP checklists.24–27

Table 1.

The impacts of a large-scale general practice collaboration (Tower Hamlets Managed General Practice Network) from quantitative studies

| Authors and journal | Title of paper | Study methods | Care package facilitated by Tower Hamlets Managed General Practice Network | Key performance indicators | Reported impact on processes and indicators of quality of care | Reported impact on costs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockman et al (2011), BMJ 24 | Improving MMR vaccination rates: herd immunity is a realistic goal | Observational. Time-series study analysis. Comparison with trends in London and England. Intervention phased in Sep 2009 to Jan 2010. Period of data analysis presented quarterly between Q1 2006 and Q3 2010 (MMR1 vaccination) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hull et al (2014), BMJ Quality and Safety25 | Improving outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes using general practice networks: a quality improvement project in East London | Observational. Time-series analysis. Comparison with trends in two neighbouring PCTs, London and England Intervention phased in Oct 2009 to Apr 2010. Period of data analysis presented yearly 2007–2012 (retinopathy screen), 2006–2012 (total cholesterol), 2006–2012 (BP), 2005–2012 (HbA1c) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hull et al (2014), Primary Care Respiratory Medicine26 | Improving outcomes for people with COPD by developing networks of general practices: evaluation of a quality improvement project in East London | Observational. Time-series analysis. Comparison with trends in London and England. Intervention phased in Apr 2010 to Jun 2010. Period of data analysis presented yearly 2010–2013 (annual review), 2005–2013 (influenza vaccination), 2005–2011 (COPD admissions) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Robson et al (2014), British Journal of General Practice27 | Improving cardiovascular disease using managed networks in general practice: an observational study in inner London | Observational study. Comparison with trends in two local PCTs, London, and England. Intervention phased in 2008 to Apr 2010. Period of data analysis presented yearly. 2009–2011 (lipid-lowering prescribing), 2004–2012 (CHD BP <150/90 mmHg), 2004–2012 (CHD cholesterol <5 mmol/l), 2004–2010 (myocardial infarction mortality in patients <75 years) |

|

|

|

|

BP = blood pressure. CHD = coronary heart disease. COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. CVD = cardiovascular disease. HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin. MDT = multidisciplinary team. MMR = measles, mumps, and rubella. MRC = Medical Research Council. PCT = primary care trust. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework. Rehab = rehabilitation.

One qualitative study examined a multisite general practice organisation with central ownership of 50 nationally dispersed GP practices. It used interviews and ethnographic observations to examine quality and safety processes, and to provide staff members’ views on job satisfaction and on patient experience (Table 2). It had a low risk of bias based on the CASP checklist.28

Table 2.

The impacts of a large-scale general practice collaboration (multipractice organisation in England) from a qualitative study

| Author and journal | Title of paper | Study methods | Reported impact on processes and indicators of quality of care | Reported impact on workforce satisfaction | Reported impact on patient experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al (2013), Journal of Health Services Research and Policy28 | Primary care quality and safety systems in the English National Health Service: a case study of a new type of primary care provider | Interviews with senior staff and owners with responsibility for policy on quality and safety. Ethnographic observation in non-clinical areas. Interviews with staff in three practices. Analysis of company documentation. Study undertaken 2011 to 2012 |

|

|

|

Quantitative studies

In 2008–2009, Tower Hamlets Primary Care Trust (PCT) (the local NHS service commissioning organisation at that time and which is now a clinical commissioning group), established eight geographically defined, managed general practice networks with a total of 36 GP practices. Each network had four or five practices and a registered population between 30 000 and 50 000. The aims of the networks at the time were to improve four clinical areas: childhood immunisations; type 2 diabetes; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; and cardiovascular disease.

Previous local enhanced services’ funding was channelled into the development of the networks and incentives for the provision of care packages were rolled out between 2008 and 2010. The PCT distributed financial incentives at network level, rather than to individual practices, to encourage peer scrutiny and the collective management of funds to achieve the PCT’s key performance indicators. Approximately £10 million per annum was spent across all networks for this initiative.27 Funding enabled staff education, information technology-enhanced recall systems, standardised data collection, the analysis of comparative feedback on performance, as well as management and shared clinical support teams across the networks. The interventions were developed by local GP clinical leaders, public health specialists, and PCT managers, with input from a management consultancy. The clinical effectiveness group, based at the local university and led by local GPs, developed the performance-monitoring dashboards and measurable key performance indicators. It also undertook the evaluations.

Results of observational time-series studies in the four targeted clinical areas appeared promising (Table 1). They demonstrated an improvement on most key performance indicators; with the average of the networks often doing better than other PCT, average London, or national trends. This included achieving targets on childhood and flu immunisation,24,26 annual review and care planning,25–27 screening,25 and, for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cardiovascular disease, increasing the number of individuals on registers and numbers referred into community rehabilitation clinics.26,27 There were also improvements in measures of health outcomes, such as achieving targets for blood pressure, cholesterol, and average glycated haemoglobin levels for patients with type 2 diabetes.25

One study compared performance in two local PCTs, which had a similar intervention package as the networks in Tower Hamlets, including the dissemination of clinical guidelines to all staff that were reinforced at central educational meetings and by standard data entry templates.27 However, the other two PCTs did not have clinical case discussions within networks or administrative target reviews, and incentives were at practice level rather than at network level. Practices in other PCTs also did not have information technology-enabled performance dashboards with traffic light ratings, and did not have network managers. Results showed that practices in the comparator PCTs did better than the national average on all measures, but not as well as Tower Hamlets.27

Qualitative findings

The multisite GP practice organisation studied was founded and owned by a small number of GPs.28 At the time of the study (2011–2012), it operated over 50 GP practices across England with a salaried workforce. It had a hierarchical form of governance with a small executive made up of the owners (Table 2).

The owners of the organisation interviewed reported commercial, reputational, and moral factors that drove them to aim to deliver high-quality care and ensure patient satisfaction. Multiple mechanisms to ensure the safety and quality of care were reportedly used, including: standardising processes, such as for incident reporting; enhancing training and inter-staff support; reducing administrative burden on frontline clinicians; optimising learning between practices; and comparing practice performance (for example, practices that under-reported adverse incidents were investigated, because this was considered a marker of possible lack of engagement with quality and safety issues). The organisation used patient surveys and ‘mystery shoppers’ to monitor performance. Feedback and benchmarking of performance were reported among member practices to create competition between practices. Authors presented a mixed picture of the ability to share learning between practices. For example, they described rapid dissemination of changes following an adverse event being common, but not all sites were maximising opportunities to improve care processes. GPs and other staff were performance managed, and if they did not meet requirements were ‘performance-managed out of the organisation’, according to one GP director interviewed.

A central call centre was set up to take telephone requests for appointments. This was intended to allow more face-to-face time between receptionists and patients in practices, and to improve efficiency in the allocation of appointments. However, interviewees provided mixed views on its effectiveness, with receptionists stating they still often had to deal with calls from the call centre, and that some patients did not like the call centre.

Patient participation groups were reported to have been involved with varying success across practices, with challenges encountered in maintaining engagement. Some staff attributed challenges in recruiting patients to antipathy towards what patients perceived as a commercial organisation providing NHS health care. One interviewee perceived that staff felt undervalued in a large company where no one local owned the practice where they worked. The recruitment and retention of staff, in particular of GPs, was problematic in some practices. This was more notable in underperforming practices that had recently been taken over by the organisation. The authors attributed some of the GP turnover to the flexibility offered by salaried or locum work compared with the ‘buy-in’ required by the traditional GP partnership business model. Staff turnover affected the relational continuity of care, and resulted in reports of patient dissatisfaction. It also posed a risk to the consistent implementation of the quality and safety procedures of the organisation, and increased the amount of time spent on staff induction procedures.

DISCUSSION

Summary

The very small number of studies available provided limited evidence on the impact on quality of care, costs, and workforce satisfaction of scaling up general practice in England. There was no robust direct evidence of impacts on patient experience, and no evidence identified on the cost-effectiveness of scaling up general practice.

The evidence from a group of networks covering 36 general practices in Tower Hamlets indicated that such networks can enable quality improvement by clearly targeting areas for improvement, with guidelines reinforced at central educational meetings, standard data entry templates, clinical case discussions within networks, administrative target reviews, incentives at network levels, and information technology-enabled performance dashboards, alongside additional clinical and management support. This is likely to require substantial financial investment and time. In the case of Tower Hamlets, the investment was approximately £10 million per year. Evidence from one multisite general practice organisation with more than 50 GP practices in England suggested that increasing scale under a single organisation could improve safety and quality processes, but might increase staff turnover, reduce continuity of care, and reduce perceived quality of patient experience.

Strengths and limitations

The literature search was comprehensive, with an expert librarian advising on multiple versions of keyword searches, and authors identifying further literature through snowball searching and seeking guidance from experts. The search methods and strict inclusion criteria improved the rigour and relevance of the reviewed literature, but the small number of studies, mostly from a single geographic area, limits the generalisability of the findings.

The review was undertaken when scaling up general practice was starting to be advocated by national policymakers.6,7 It highlights the limited good-quality evidence to support this approach at the time. Further work has since been undertaken,9,29,30 and more research is underway, which may help fill some of the gaps identified.31–33

This review is complemented by a review of the wider academic and grey literature examining the development and impact of national and international initiatives with similarities to large-scale general practice organisations in England, such as specialist clinical networks, GP-led commissioning, out-of-hours cooperatives, and integrated care initiatives.23

Comparison with existing literature

Despite the recent focus by national policymakers in England on increasing organisational size to improve quality of care and generate efficiencies in general practice, there is no consistent association between scale, quality of care, or the generation of efficiency savings in the healthcare literature.23 A wide range of factors other than size alone influence performance, including the availability of resources, the quality of clinical leadership, and pre-existing relationships in the local health economy.34–40 The time and resources involved in health service reorganisations such as scaling up organisations have often been underestimated, and anticipated benefits have not always been delivered.20,41–43 Although patients may value increased routes of access through scaling up, new access routes may not be well received by all patients.20,22,39 For example, the importance of providing continuity of care for those who most need it has frequently been identified as desirable but may be harmed by providing general practice care through larger organisations.44

Experience from similar initiatives both in the UK and internationally highlights important trade-offs that exist in scaling up, such as between being small enough to maintain flexibility and inclusive decision-making processes and being of sufficient size to bear financial risks as well as exert power to influence the local health economy.45,46 It also highlights that giving GPs autonomy and engaging them in decision making may well increase the likelihood of large-scale general practice collaborations forming successfully; however, this may also result in duplicated efforts, inequity in participation, and complexity of organisational forms.46–49

Implications for research and practice

The pressures that GP practices are facing at present in England are significant. Although these circumstances make finding better ways to deliver care pressing, using clinicians’ time to address organisational issues represents an opportunity–cost to patient care.

There is currently little robust research to indicate with confidence that the expectations placed on larger-scale general practice provider collaborations in England will be met, or to identify with confidence the potential unintended consequences. As more GP collaborations form and mature in England, evaluation of their impacts will be fundamental to better understand which types work best, in which circumstances, for whom, how, and why. This ideally should happen before large-scale general practice is pursued as national policy across England.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Judith Smith who led on the early research project development; Natasha Curry who provided guidance on this literature review in its initial stages; Rod Sheaff who provided comments on the literature review in the final stages; Sally Hull and John Robson who reviewed an early draft of the section on Managed General Practice Networks in Tower Hamlets and provided additional information; and Michael Kidd, Ruth Wilson, and Job Metsemakers for insights into large-scale general practice collaborations internationally.

Funding

Luisa M Pettigrew was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) In-Practice Fellowship in the Department of Health Services Research and Policy at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. This study formed part of a larger piece of work in collaboration with the Nuffield Trust.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

Rebecca Rosen is an external GP on Tower Hamlets Clinical Commissioning Group for primary care commissioning and Director of Greenwich Health GP Federation. The other authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Sheaff R. Plural provision of primary medical care in England, 2002–2012. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013;18(2 Suppl):20–28. doi: 10.1177/1355819613489544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith J, Holder H, Edwards N, et al. Securing the future of general practice: new models of primary care. 2013. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/securing-the-future-of-general-practice-new-models-of-primary-care (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 3.Field S, Gerada C, Baker M, et al. Primary care federations: putting patients first. A plan for primary care in the 21st century from the Royal College of General Practitioners. 2008. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/primary-care-federations-putting-patients-first.aspx (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 4.Imison C, Williams S, Smith J, Dingwall C. Toolkit to support the development of primary care federations. 2010. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/clinical-and-research/a-to-z-clinical-resources/~/media/19A1F84B41A04DFE8AAAF2F65FD3D757.ashx (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 5.Addicott R, Ham C. Commissioning and funding general practice: making the case for family care networks. 2014. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/commissioning-and-funding-general-practice-kingsfund-feb13.pdf (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 6.NHS England Chapter three — what will the future look like? New models of care. Five year forward view. 2014:17–28. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS England New care models The multispecialty community provider (MCP) emerging care model and contract framework. 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/mcp-care-model-frmwrk.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 8.NHS England Integrating care: contracting for accountable models. NHS England. 2017. Accountable Care Organisation (ACO) contract package — supporting document. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/1693_DraftMCP-1a_A.pdf (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 9.Rosen R, Kumpunen S, Curry N, et al. Is bigger better? Lessons for large-scale general practice. 2016. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/large-scale-general-practice-web-final.pdf (accessed 23 Jan 2018)

- 10.Greenhalgh T, Peacock R. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: audit of primary sources. BMJ. 2005;331(7524):1064–1065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) CASP checklists. 2017. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 12.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosen R, Parker H. New models of primary care: practical lessons from early implementers. 2013. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-01/new-models-of-primary-care.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 14.Barr F. How providing general practice at scale can benefit patients. Medeconomics. 2016. Feb 11, http://www.medeconomics.co.uk/article/1382460 (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 15.Evans R. Case study: the benefits of being a larger practice. Medeconomics. 2016. Jul 1, http://www.medeconomics.co.uk/article/1400910 (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 16.Royal College of General Practitioners. July clinical news articles —the working at scale edition. London: RCGP; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.GP Frontline. Can working at scale deliver for patients? GPFrontline. 2016;4:12–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith M. How a GP federation is cutting A&E workload. Medeconomics. 2015. Oct 1, http://www.medeconomics.co.uk/article/1366707 (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 19.Erens B, Wistow G, Mounier-Jack S, et al. Early evaluation of the integrated care and support pioneers programme: interim report. 2015. http://www.piru.ac.uk/assets/files/Early%20evaluation%20of%20IC%20Pioneers,%20interim%20report.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 20.RAND Europe, Ernst & Young LLP; prepared for the Department of Health National evaluation of the Department of Health’s integrated care pilots. 2012 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215103/dh_133127.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheaff R, Halliday J, Øvretveit J, et al. Integration and continuity of primary care: polyclinics and alternatives — a patient-centred analysis of how organisation constrains care co-ordination. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2015;(3):35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SQW, Mott MacDonald. Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund: improving access to general practice. First evaluation report: October 2015. NHS England Publication Gateway Reference Number 04123. 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/pmcf-wv-one-eval-report.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 23.Pettigrew L, Mays N, Kumpunen S, et al. Large-scale general practice in England: what can we learn from the literature? 2016. Technical Report. http://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/3450732/1/Large-scale%20general%20practice.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 24.Cockman P, Dawson L, Mathur R, Hull S. Improving MMR vaccination rates: herd immunity is a realistic goal. BMJ. 2011;343:d5703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hull S, Chowdhury TA, Mathur R, Robson J. Improving outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes using general practice networks: a quality improvement project in East London. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(2):171–176. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hull S, Mathur R, Lloyd-Owen S, et al. Improving outcomes for people with COPD by developing networks of general practices: evaluation of a quality improvement project in East London. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14082. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2014.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robson J, Hull S, Mathur R, Boomla K. Improving cardiovascular disease using managed networks in general practice: an observational study in inner London. Br J Gen Pract. 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X679697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Baker R, Willars J, McNicol S, et al. Primary care quality and safety systems in the English National Health Service: a case study of a new type of primary care provider. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1355819613500664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Association of Primary Care. Does the primary care home make a difference? 2017. http://napc.co.uk/does-the-primary-care-home-make-a-difference/ (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 30.Kumpunen S, Rosen R, Kossarova L, Sherlaw-Johnson C. Primary care home: evaluating a new model of primary care. 2017. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/files/2017-08/pch-report-final.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 31.McDonald R. Learning about and learning from GP federations in the English NHS: a qualitative investigation. 2016. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419604/#/ (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 32.Turner A, Mulla A, Booth A, et al. An evidence synthesis of the international knowledge base for new care models to inform and mobilise knowledge for multispecialty community providers (MCPs) Syst Rev. 2016;5:167. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0346-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheaff R. From programme theory to logic models for multi-specialty community providers: a realist evidence synthesis. 2016. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/157734/#/ (accessed 2 Feb 2018) [PubMed]

- 34.Brown BB, Patel C, McInnes E, et al. The effectiveness of clinical networks in improving quality of care and patient outcomes: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:360. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1615-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ng CW, Ng KP. Does practice size matter? Review of effects on quality of care in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2013. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X671588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.McDonald R, Cheraghi-Sohi S, Tickle M, et al. The impact of incentives on the behaviour and performance of primary care professionals. 2010. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/netscc/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1618-158_V06.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 37.Baeza JI, Fitzgerald L, McGivern G. Change capacity: the route to service improvement in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2008;16(6):401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goodwin N, Peck E, Freeman T, Posaner R. Managing across diverse networks of care: lessons from other sectors. Report to the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO) 2004. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/adhoc/39-policy-report.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 39.Leibowitz R, Day S, Dunt D. A systematic review of the effect of different models of after-hours primary medical care services on clinical outcome, medical workload, and patient and GP satisfaction. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):311–317. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bojke C, Gravelle H, Wilkin D. Is bigger better for primary care groups and trusts? BMJ. 2001;322(7286):599–602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7286.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller R, Peckham S, Coleman A, et al. What happens when GPs engage in commissioning? Two decades of experience in the English NHS. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2016;21(2):126–133. doi: 10.1177/1355819615594825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nolte E, Pitchforth E. What is the evidence on the economic impacts of integrated care? 2014. http://observgo.uquebec.ca/observgo/fichiers/12008_GSS-1.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 43.Fulop N, Protopsaltis G, Hutchings A, et al. Process and impact of mergers of NHS trusts: multicentre case study and management cost analysis. BMJ. 2002;325(7358):246. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7358.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Freeman G, Hughes J. Continuity of care and the patient experience. London: King’s Fund; 2010. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/Continuity.pdf (accessed 23 Jan 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ham C. GP budget holding: lessons from across the pond and from the NHS. University of Birmingham; 2010. HMSC policy paper 7. http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/758/1/HSMC-policy-paper7.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horvath J. Review of Medicare locals: report to the Minister for Health and Minister for Sport. 2014. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/review-medicare-locals-final-report (accessed 2 Feb 2018)

- 47.Hutchison B, Levesque JF, Strumpf E, Coyle N. Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q. 2011;89(2):256–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Checkland K, McDermott I, Coleman A, Perkins N. Complexity in the new NHS: longitudinal case studies of CCGs in England. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010199. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guthrie B, Davies H, Greig G, et al. Delivering health care through managed clinical networks (MCNs): lessons from the North. 2010. Report for the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme. http://www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/SDO_FR_08-1518-103_V01.pdf (accessed 2 Feb 2018)