Abstract

Aims and objectives

This study draws on a life course perspective to evaluate, in a sample of sexual minority women: (1) the relationship between age at reaching sexual identity milestones and risk of suicidal ideation, (2) developmental stages or stages of sexual identity development that represent greatest risk, and (3) the relationship between age of reaching milestones and parental support.

Background

Research has found higher rates of suicidal ideation among sexual minority women than heterosexual women. Evidence suggests this may be partly accounted for by contextual risk factors such as sexual identity development and parental support. However, it remains unclear whether there are stages of particularly high risk.

Design

This is a cross-sectional study. Data come from a prospective study of sexual minority women that used convenience and respondent driven sampling methods.

Methods

Using logistic regression methods, we examined associations among age at sexual identity developmental milestones, parental support, and suicidal ideation in a large (N=820), ethnically diverse sample of sexual minority women.

Results

Compared with women who first wondered about their sexual identity in adulthood, those who first wondered in early, middle or late adolescence had greater odds of lifetime suicidal ideation. Younger age at subsequent milestones (first decided or first disclosed) was not associated with heightened risk of suicidal ideation. Parental support was independently associated with suicidal ideation.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that where one is in the process of identifying as sexual minority may be more important than age in understanding risk of suicidal ideation in this population. As individuals come to accept and integrate their sexual minority identity risks associated with younger age diminish. Nurses and other health care providers who work with youth should routinely ask about sexual orientation and suicidal ideation and be aware that youth in the earliest stages of coming out as sexual minority may be at particularly high risk of suicide.

Keywords: Sexuality, Mental Health, Women’s Health, Suicide, Suicidal Ideation, Sexual Minority Women, Lesbian, Bisexual Women, Sexual Minority Youth

INTRODUCTION

Research suggests that the prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempted suicide are significantly higher among lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) people compared to heterosexuals (Meyer et al. 2008). This disparity appears to exist among both adolescent and adult LGB individuals (Meyer et al. 2008; Silenzio et al. 2007). Among sexual minority women specifically, there is evidence that the risk of suicidal behavior is higher compared to heterosexual women (Matthews et al. 2002). Accumulating evidence suggests that differences in both individual (e.g., depression and internalized homophobia) and contextual (e.g., experiences of discrimination and lower levels of social support) risk factors may help to explain higher rates of suicidality among LGB people (House et al. 2011; Ryan et al. 2009).

Nurses and other health care providers are well positioned to address this public health issue. There is evidence that approximately 45% of suicide victims had contact with their primary care provider within one month of the suicide (Luoma et al. 2014). There is also evidence that primary-care-based suicide prevention interventions can be effective (Mann et al. 2005). However, to effectively address and intervene, providers must have an understanding of those who are most at risk of suicidal ideation and behavior.

In this paper we take a life course approach to better understand how developmental stage at sexual identity milestones may be associated with suicidal ideation in sexual minority women. The life course framework takes into account biographical and social contexts, and recognizes the influence of these factors peoples’ lives and well-being. Further, this perspective considers the relevance of developmental stage during critical life transition points and acknowledges the influence such transitions can have in both the short- and long-term (Elder 1994; Elder 1998).

BACKGROUND

Sexual identity developmental milestones mark critical transition points in the life course of sexual minorities. Some of the most commonly recognized milestones include first awareness of same-sex attraction, first same-sex sexual contact, first self-acknowledgement of sexual minority identity, and first disclosure of sexual identity (Bilodeau & Renn 2005; Cass 1979; Troiden 1988). According to the life course framework, the same experiences may impact individuals in different ways depending on when they occur in the life course (Elder 1994; Elder 1998). Therefore, the developmental stage at which individuals reach these milestones may be an important factor in understanding both the negative and positive consequences.

Early models of sexual minority identity development assumed a linear process in which individuals experience increasing self-acceptance as they move through the milestones (Cass 1979; Troiden 1988). More recent research has acknowledged limitations with these models because they lack the flexibility to accommodate individual and nuanced differences in the process; they are oversimplified in their delineation of a linear process that always culminates in a static homosexual identity (Diamond 2005; Eliason & Schope 2007). Instead it appears that while most LGB individuals experience multiple milestones, there are important individual differences in their timing and sequence (Calzo et al. 2011).

Although researchers have begun to move away from the linear perspective of sexual identity development, there continues to be an acknowledged process of increased acceptance and positive identity integration across studies. The initial milestone, which is usually wondering about or awareness of same-gender attraction, is explained as a period of inner turmoil, feelings of alienation, and identity confusion (Bilodeau & Renn 2005; Cass 1979; Troiden 1988). However, as individuals progress to the subsequent milestones of self-identification and first disclosure as a sexual minority person, they develop an acceptance of their same-gender attraction and their identity as a sexual minority becomes internally integrated. Thus, where one is in the process of their sexual identity development may be important to understanding associations with mental health.

Positive outcomes of reaching sexual identity milestones and adopting an LGB identity can include improved self-esteem, sense of community, sense of living authentically, as well as improved relationships with romantic partners and parents (Riggle et al. 2008). Yet, adopting a sexual minority identity can also lead to experiences of stigma and discrimination, which can impact mental health and may contribute to suicidal ideation (Burgess et al. 2007). Individuals who have disclosed their LGB identity often report experiencing rejection from parents, workplace discrimination and harassment, and victimization in school and community settings (Rosario et al. 2009).

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals who reach sexual identity milestones at young ages, such as in early or middle adolescence, may be exposed to particularly high levels of stigma and low levels of social support (Almeida et al. 2009; Russell et al. 2014). Because adolescence is a period when concern about conforming to peer norms is at its peak (American Psychological Association 2002; Smetana et al. 2006), those who do not conform may experience stigma and feelings of isolation from peers. Early adolescence is also a time when conflict with parents is high (American Psychological Association 2002; Smetana et al. 2006) and LGB youth, in particular, may experience intensified conflict regarding their failure to meet parental expectations (Saltzburg 2004). Younger age at reaching sexual minority identity milestones may, therefore, be an individual risk factor for suicidal behavior.

Previous studies have found an association between the age at which individuals reach milestones and suicidality. For example, age of first disclosure appears to be positively correlated with age at suicidal ideation (Igartua et al. 2003). Further, there is evidence that younger age at multiple milestones is associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior (D’Augelli & Hershberger 1993; D’Augelli et al. 2001). However, because these studies did not distinguish between different developmental stages (e.g., early, middle or late adolescence) of reaching milestones, it is unclear whether there are periods of particularly high risk.

Assessing this relationship through the lens of the life course perspective permits the overlay of emotional/cognitive development with sexual identity development. Rather than examining incremental differences by age this approach permits the examination of how shifts in cognitive development may coincide with sexual identity development to influence risk of suicidal ideation. Early adolescence may be a time of increased vulnerability because this is usually when physical sexual development begins and sexual identity development progresses. At the same time, teens in early adolescence generally experience emotional separation from parents, heightened vulnerability to peer influence and susceptibility to depression—which is more pronounced in girls than boys (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2011; American Psychological Association 2002). As teens move into middle adolescence they are known to experience concerns about appearance, fluctuations in self-esteem, an increase in impulsive and health risk behaviors and a desire to separate from parents (Christie & Viner 2005). These factors contribute to difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control, both of which are associated with suicidality (Christie & Viner 2005; Dougherty et al. 2004). Late adolescence is characterized by a firmer sense of identity, greater emotional stability and the development of social autonomy (Christie & Viner 2005). These three periods, therefore, signify important developmental transitions that, when combined with LBG identity development, may represent different levels of risk for suicidal ideation. As the third leading cause of death among 10- to 24-year-olds, suicide is an important health issue for all adolescents (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2012) but especially for LGB youth who must additionally contend with stigma regarding their sexual identity.

In exploring whether earlier age at milestones is associated with increased suicidality, it is important to consider the role of parental support. Research suggests that many LGB adolescents report low levels of parental support (Needham & Austin 2010). There is also evidence that LGB adolescents who disclose their sexual identity to their parents risk rejection, which is linked with negative mental health outcomes (Rosario et al., 2009; Ryan et al. 2009). Further, research suggests that LGB individuals generally report more perceived support from their mothers compared to their fathers (D’Augelli 2002) and are also more likely to disclose their sexual orientation to their mothers (Savin-Williams & Ream 2003). In this study we examine the relationship between sexual minority women’s developmental stage of reaching milestones and support from their mother and father.

Lastly, there is evidence of high rates of childhood sexual and physical abuse among sexual minority women (Hughes et al. 2010). There is also a known link between childhood abuse experiences and suicidality among sexual minority women (House et al. 2011). Therefore, this is an important factor to take into account when examining associations with suicidal ideation in this population.

Current Study

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate, in a sample of sexual minority women: (1) the relationship between age at reaching sexual identity milestones and risk of suicidal ideation, (2) developmental stages or stages of sexual identity development that represent greatest risk, and (3) the relationship between age of reaching milestones and parental support. Hypotheses were that: (H1) younger age at each of three sexual identity milestones—first wondering about, first deciding about, first disclosing sexual minority identity—will be associated with increased risk of suicidal ideation; (H2) younger age at sexual identity milestones will be associated with less support from SMW’s mothers and fathers.

METHODS

Participants

Data are from the Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women (CHLEW) study, a prospective study of self-identified sexual minority (e.g., lesbian, bisexual) women in the Chicago metropolitan area. Data were collected in face-to-face interviews conducted by trained female interviewers at three time periods (waves) over 10 years. Participants enrolled at wave 1 (2000–01) were recruited through various sources including community-based organizations, informal community groups, and outreach to individual social networks. Interested women were instructed to contact the study office for a brief screening interview to determine eligibility. Women who indicated that their sexual identity was heterosexual or bisexual were not invited to participate in the study. Despite this screening process 11 women identified as bisexual in the study interview. Participants enrolled at wave 1 were also invited to participate in interviews in 2004–5 (wave 2) and 2010–12 (wave 3). At wave 3, a new cohort of younger (aged 18–25), African American and Latina and bisexual women were added to the study and interviewed for the first time. The new cohort was recruited using a modified version of respondent driven sampling, which is effective in drawing samples from hidden or hard to reach populations (Heckathorn 1997; Heckathorn 2002). Women were eligible to participate if they were English speaking, at least 18 years old and lived in the Chicago metropolitan area. Data for the current analysis is from baseline interviews collected in 2000–01 for the original sample and in 2010–12 for the new sample. The combined sample included 820 women aged 18 and older.

Measures

Developmental Stage at Sexual Minority Identity Milestones

This study assessed age at three milestones associated with the sexual identity development process. Participants were asked the following questions: (1) “At what age did you first wonder whether you might be lesbian/gay/other?” (first wonder); (2) “At what age did you first decide that you were lesbian/gay/other?” (first decide); and (3) “At what age did you first tell someone you were lesbian/gay/other?” (first disclosure). Previous research suggests that there is sufficient reliability when asking adult survey participants to report on age at onset of behaviors that are mostly initiated in adolescence (Johnson & Mott 2014). Furthermore, the methods of data collection used in this study (i.e. computer self-administered questions, highly trained interviewers) help to ensure validity and reliability of measuring assessing sexual behavior (Johnson & Smith 2013).

Age at reaching these milestones was divided according to whether the milestone occurred in adulthood or in early, middle, or late adolescence. The literature regarding the age range for each stage of adolescence varies, with early adolescence beginning as young as age 10 and late adolescence lasting to age 24 (Smetana et al. 2006). In the current study, early adolescence was categorized as between ages 10 and 14, middle adolescence between 15 and 16, and late adolescence between 17 and 21 (World Health Organization 2013). Because there were only a few participants who reached these milestones prior to age 10, those who reported reaching the milestones in preadolescence (prior to age 10) were combined with early adolescence (ages 10–14).

Lifetime Suicidal Ideation

Participants were asked, “Have you ever felt so low you thought of committing suicide?” Women were classified as having a history of suicidal ideation if they responded yes to this question. This measure of suicidal ideation is the same as used in previous national studies, including the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey (Weissman et al. 1999) and the US National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al. 1999).

Parental Support In Childhood

Parental support when growing up was assessed by asking participants to rate separately their mother’s and father’s support on a scale from 1 to 5, in response to the following question: “Please pick the number that best describes how your father/mother was to you while you were growing up? If he/she tended to be accepting, praising, loving pick a higher number. If he/she was more rejecting, belittling, or not so loving pick a lower number.” Responses to this question provides a global assessment of support received from the participant’s mother and father during childhood.

Birth Year

Birth year was included to examine and account for historical effects in terms of whether younger age of participants was associated with more support from the mother and father during childhood.

Sociodemographic Variables

Because of their potential effect on the associations of interest, our analyses controlled for race/ethnicity, birth year, education, income, sampling wave, and sexual identity. Regarding sexual identity, the women were asked which of the following four categories best described their sexual identity—only lesbian, mostly lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, only heterosexual, or other (please specify). The current analyses combined lesbian, bisexual, and other (e.g., queer, prefer not to be labeled) categories because identity categories and labels can change substantially across adolescence and over the life course (Diamond 2005; Rosario et al. 2005), yet many experiences associated with having a sexual minority identity, such as low parental support, tend to be similar (Ryan et al. 2009). Furthermore, sexual identity categories were included as control variables to account for differences in outcomes by sexual identity. There were no women who identified as only heterosexual and only one woman identified as mostly heterosexual; this participant is included in the “other” identity category.

Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse were also included in the analysis as control variables. These experiences were assessed by asking participants, “Do you feel that you were physically abused by your parents or other family members when you were growing up?” and “Do you feel that you were sexually abused when you were growing up?” Response choices for both of these were yes or no.

Respondents provided informed consent prior to each interview. All survey methods and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS v21. A series of four logistic regression models were used to test hypothesis 1 that younger age at reaching milestones is associated with greater risk of suicidal ideation. Participants who reached these milestones in early, middle or late adolescence were compared to those who reached the milestone in adulthood (age 22 or older). Lifetime suicidal ideation was the outcome in each model and each analysis controlled for the sociodemographic variables described above. The first model included all three milestones at three stages of adolescence (nine focal predictor variables) but because of multicollinearity issues, each milestone at the three stages of adolescence were also assessed separately in models two, three, and four. Two linear regression models were used to test hypothesis two, that younger age at milestones is associated with less support from the mother and father.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic Characteristics and Study Variables

Demographics characteristics of the sample (N=820) are summarized in Table I. The sample was diverse in terms of age (M=35.63, SD=11.94, range=18–83 years), race (37% White, 35% African American, 24.5% Latina, 3.5% other race/ethnicity), and sexual identity (59.6% only lesbian, 20.4% mostly lesbian, 16.2% bisexual, and 3.8% other sexual identity). Approximately 43% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and nearly half (47.8%) reported household incomes between $20,000 and $74,999. Approximately 46% of the sample reported lifetime suicidal ideation. The average score for perception of maternal support was 3.96 (SD=1.29) and for paternal support 3.58 (SD=1.36; range of 1=mostly rejecting to 5=mostly loving for both).

Table I.

DEMOGRAPHICS CHARACTERISTICS OF SAMPLE OF SEXUAL MINORITY WOMEN (N=820)

| Characteristic | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 303 (37) | |

| African American | 287 (35) | |

| Latina | 201 (24.5) | |

| Other (e.g., Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian) | 29 (3.5) | |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Only Lesbian | 488 (59.6) | |

| Mostly Lesbian | 167 (20.4) | |

| Bisexual | 133 (16.2) | |

| Other (e.g., queer, prefer no label) | 32 (3.8) | |

| Education Level | ||

| High School or less | 179 (21.9) | |

| Some college | 284 (34.7) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 178 (21.8) | |

| Grad/professional degree | 177 (21.6) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.2) | |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20,000 | 285 (36.2) | |

| $20,000–$39,999 | 186 (23.6) | |

| $40,000–$74,999 | 191 (24.2) | |

| $75,000 or more | 126 (16) | |

| Missing | 32 (3.9) | |

| Lifetime Suicidal Ideation Present | 380 (46.3) | |

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|

| ||

| Parental Support | ||

| Support from Mother | 3.96 (1.29) | 1–5* |

| Support from Father | 3.58 (1.36) | 1–5* |

| Age | 35.63 (11.94) | 18–83 |

1=Most Rejecting, 5=Most Loving

Table II provides information on the distribution of developmental age of sexual identity development milestones. The average age that participants first wondered about being lesbian or bisexual was 15.2 years (SD=6.81), first decided was 20.8 (SD=7.83), and first disclosed their sexual minority identity was 22.01 (SD=8.16). The number and percent of participants reaching each of these milestones during early, middle, or late adolescence is also summarized in Table II.

Table II.

DISTRIBUTION OF DEVELOPMENTAL STAGE AT EACH MILESTONE FOR SAMPLE OF SEXUAL MINORITY WOMEN (N=820)

| Variables | Mean (SD) | Early Adolescence (age 10–14) n (%) |

Middle Adolescence (age 15–16) n (%) |

Late Adolescence (age 17–21) n(%) |

Adulthood (age over 21) n (%) |

Missing data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milestone | ||||||

| Age first wondered if sexual minority | 15.20 (6.81) | 427 (52.1) | 116 (14.1) | 165 (20.1) | 104 (12.7) | 8 (1%) |

|

| ||||||

| Age first decided sexual minority identity | 20.80 (7.83) | 140 (17.1) | 101 (12.3) | 288 (35.1) | 287 (35) | 4 (.5%) |

|

| ||||||

| Age first disclosed sexual minority identity | 22.01 (8.16) | 84 (10.2) | 98 (12.0) | 315 (38.4) | 304 (37.1) | 19 (2.3) |

Bivariate correlations between age at reaching each of the three sexual identity milestones were examined to assess for multicollinearity. The correlation between age of first deciding about and disclosing sexual minority identity was especially high (r=0.872, p<.001), which could cause problems in further multivariate analysis. This is addressed in the logistic regression analysis results below.

Developmental Stage at Sexual Minority Identity Milestones and Suicidal Ideation

As presented in Table III, all nine of the milestone variables were included as independent variables in the first model. Women who first wondered about their sexual identity in early (OR=2.96, 95%CI: 1.48–5.9, p<.01), middle (OR=3.08, 95%CI: 1.42–6.70, p<.01), or late adolescence (OR=2.67, 95%CI: 1.31–5.45, p<.01) were significantly more likely to experience lifetime suicidal ideation compared to those who reached this milestone in adulthood. There were no significant differences between women who first decided or disclosed in early, middle, or late adolescence and those who reached these milestones in adulthood. In the full model, those who reported more support from their mother were less likely to report a history of suicidal ideation (OR=0.85, 95%CI: 0.73–0.99. p<.05) as were those who reported more support from their father (OR=0.85, 95%CI: 0.73–0.97, p<.05). African American women were less likely to report suicidal ideation than White women (OR=0.61, 95%CI: 0.37–1.00, p<.05). Those who reported childhood sexual abuse were more likely to report suicidal ideation (OR=1.78; 95%CI: 1.18–2.67, p<.01) compared to women who did not report childhood sexual abuse. While these results suggest that first wondering about being a sexual minority in any stage of adolescence compared to adulthood increases the risk for suicidal ideation, the level of risk may be inaccurate because of multicollinearity between the age of first deciding and age of first disclosing variables. To address this, separate models were fit for each of the three milestone variables.

Table III.

Logistic Regression Models of Sexual Identity Milestones at Three Stages of Adolescence Predicting Suicidal Ideation in Sample of Sexual Minority Women

| First Model (n=536) | Second Model (n=545) | Third Model (n=543) | Fourth Model (n=540) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model | Model for Age First Wondered | Model for Age First Decided | Model for Age First Disclosed | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |

| First Wondered - Earlya | 2.96** | 1.48–5.9 | 2.79** | 1.55–5.04 | - | - | - | - |

| First Wondered – Middlea | 3.08** | 1.42–6.70 | 2.77** | 1.34–5.73 | - | - | - | - |

| First Wondered – Latea | 2.67** | 1.31–5.45 | 2.26* | 1.18–4.36 | - | - | - | - |

| Decided – Earlyb | 1.13 | 0.43–2.92 | - | - | 1.62 | 0.90–2.89 | - | - |

| Decided – Middleb | 0.84 | 0.32–2.19 | - | - | 1.09 | 0.58–2.05 | - | - |

| Decided – Lateb | 0.92 | 0.42–2.01 | - | - | 1.23 | 0.79–1.92 | - | - |

| Disclosed – Earlyc | 1.01 | 0.35–2.93 | - | - | - | - | 1.55 | 0.74–3.24 |

| Disclosed – Middlec | 0.83 | 0.31–2.19 | - | - | - | - | 1.08 | 0.56–2.05 |

| Disclosed – Latec | 0.94 | 0.45–2.00 | - | - | - | - | 1.26 | 0.82–1.93 |

| Childhood Physical Abuse | 1.15 | 0.70–1.88 | 1.21 | 0.75–1.96 | 1.12 | 0.69–1.80 | 1.12 | 0.70–1.79 |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | 1.78** | 1.18–2.67 | 1.69* | 1.14–2.53 | 1.89** | 1.27–2.82 | 1.79** | 1.20–2.67 |

| African-Americand | 0.61* | 0.37–1.00 | 0.58* | 0.36–0.94 | 0.63 | 0.39–1.03 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.06 |

| Latinad | 0.79 | 0.48–1.30 | 0.77 | 0.47–1.26 | 0.80 | 0.49–1.31 | 0.84 | 0.51–1.37 |

| Other Raced | 0.68 | 0.29–1.68 | 0.70 | 0.29–1.69 | 0.73 | 0.30–1.76 | 0.76 | 0.31–1.82 |

| Birth Year | 1.00 | 0.99–1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98–1.02 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 |

| Education | 0.94 | 0.77–1.16 | 0.96 | 0.79–1.16 | 0.95 | 0.78–1.15 | 0.93 | 0.76–1.13 |

| Income | 0.97 | 0.93–1.00 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.00 |

| Wave 3e | 0.85 | 0.50–1.44 | 0.88 | 0.52–1.48 | 0.83 | 0.49–1.40 | 0.83 | 0.50–1.40 |

| Bisexualf | 1.25 | 0.63–2.47 | 1.14 | 0.59–2.20 | 1.08 | 0.57–2.05 | 1.17 | 0.60–2.26 |

| Mostly Lesbianf | 0.83 | 0.52–1.31 | 0.79 | 0.51–1.23 | 0.81 | 0.52–1.26 | 0.74 | 0.48–1.15 |

| Other Sex IDf | 3.86 | 0.76–19.47 | 3.85 | 0.76–19.42 | 4.01 | 0.79–20.40 | 4.09 | 0.81–20.73 |

| Support from Mother | 0.85* | 0.73–0.99 | 0.86 | 0.74–1.00 | 0.84* | 0.73–0.97 | 0.84* | 0.72–0.97 |

| Support from Father | 0.85* | 0.73–0.97 | 0.83* | 0.72–0.96 | 0.83** | 0.72–0.95 | 0.84* | 0.73–0.96 |

Reference category = First Wondered– Adulthood;

Reference category = First Decided - Adulthood;

Reference category = First Disclosed - Adulthood;

Reference category = White.;

Reference category = Wave 1;

Reference category = Only Lesbian;

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05

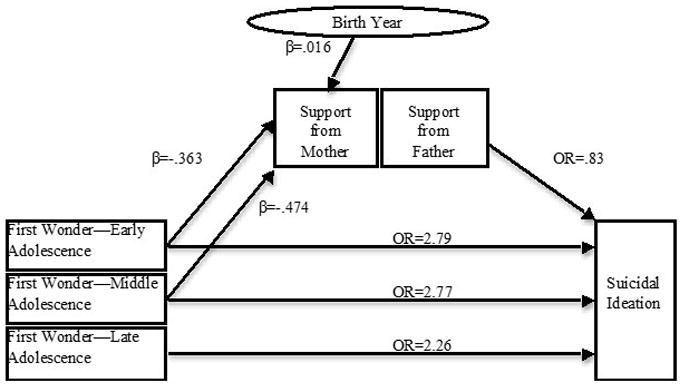

The second model included first wondered in early, middle, or late adolescence and the same set of control variables (Table III). Similar to the previous results, findings suggest that those who first wondered about being lesbian or bisexual in early, middle, or late adolescence were significantly more likely (OR=2.79, 95%CI: 1.55–5.04, p<.01; OR=2.77, 95%CI: 1.34–5.73, p<.01; and OR=2.26, 95%CI: 1.18–4.36, p<.05, respectively) to experience lifetime suicidal ideation compared to those who reached this milestone in adulthood (Table III; Figure 1)1. Additionally, in this model, participants with higher levels of support from their father were less likely to experience lifetime suicidal ideation (OR=0.83, 95%CI: 0.72–0.96, p<.05). Support from the mother was moderately, but not significantly, associated with lower risk of suicidal ideation (OR=0.86 and a 95%CI=0.74–1.00). African American women were significantly less likely than White women to report lifetime suicidal ideation (OR=0.58, 95%CI: 0.36–0.94, p<.01), and those who reported childhood sexual abuse were more likely to report suicidal ideation (OR=1.69; 95%CI: 1.14–2.53, p<.05) compared to those not reporting childhood sexual abuse.

Figure 1.

Significant associations among developmental age at milestones, parental support, birth year and suicidal ideation in sample of sexual minority women (N=820).

The third and fourth models assessed first deciding about being a sexual minority and first disclosing sexual minority identity in early, middle, and late adolescence, respectively. Consistent with Model 1, there were no significant differences in suicidal ideation between those who reached either of these milestones in early, middle, or late adolescence and those who reached these milestones in adulthood. Those with more maternal support and more paternal support were less likely to report suicidal ideation in both the third (OR=0.84, 95%CI: 0.73–0.97, p<.05, and OR=0.83, 95%CI: 0.72–0.95, p<.01) and fourth (OR=0.84, CI:0.72–0.97, p<.05 and OR=0.84, CI:0.73–0.96, p<.05) models. The relationship between African American race and lifetime suicidal ideation was no longer significant. However, childhood sexual abuse continued to be positively associated with risk of suicidal ideation.

Developmental Stage at Sexual Minority Identity Milestones and Parental Support

As shown in Table IV, first wondering about being a sexual minority in early, middle, or late adolescence was not significantly associated with paternal support. However, there were significant associations with maternal support. Those who first wondered in early and middle adolescence reported significantly less support from their mothers (B=−0.363, p<.05; B=−0.474, p<.05, respectively; Figure 1) compared to those who first wondered in adulthood. Participants who first decided they were lesbian or bisexual in middle adolescence reported lower levels of maternal support (B=−0.359, p<.05; Figure 1). This finding suggests that sexual minority women who first wondered about their sexual identity at younger ages reported lower levels of maternal support than those who first wondered about their sexual identity in adulthood.

Table IV.

MULTIPLE LINEAR REGRESSION OF SEXUAL IDENTITY MILESTONES AT THREE STAGES OF ADOLESCENCE PREDICTING SUPPORT FROM MOTHER AND FATHER (N=820)

| Support from Mother | Support from Father | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age first Wondered | Age First Decided | Age First Disclosed | Age first Wondered | Age First Decided | Age First Disclosed | |

|

| ||||||

| B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | B (SE) | |

| First Wondered— Earlya | −.363 (.156)* | - | - | −.216 (.174) | - | - |

| First Wondered— Middlea | −.474 (.193)* | - | - | −.041 (.218) | - | - |

| First Wondered— Latea | −.225 (.173) | - | - | .012 (.194) | - | - |

| First Decided— Earlyb | - | −.046 (.159) | - | - | −.145 (.180) | - |

| First Decided— Middleb | - | −.359 (.171)* | - | - | −.123 (.199) | - |

| First Decided— Lateb | - | −.041 (.121) | - | - | −.048 (.140) | - |

| First Disclosed— Earlyc | - | - | −.080 | - | - | −.198 (.222) |

| First Disclosed— Middlec | - | - | −.143 | - | - | .169 (.203) |

| First Disclosed— Latec | - | - | .038 | - | - | .029 (.135) |

| Childhood Physical Abuse | −.941 (.120)*** | −.916 (.121)*** | −.895 (.120)*** | −.712 (.138)*** | −.740 (.139) | −.707 (.139)*** |

| Childhood Sexual Abuse | −.216 (.107)* | −.249 (.107)* | −.279 (.107)** | −.427 (.123)** | −.454 (.124) | −.449 (.123)*** |

| African Americand | .221 (.128) | .192 (.128) | .167 (.129) | .071 (.149) | .056 (.150) | .049 (.151) |

| Latinad | .142 (.136) | .161 (.136) | .183 (.137) | .192 (.155) | .162 (.155) | .135 (.155) |

| Other Raced | .022 (.257) | −.010 (.258) | .005 (.256) | .189 (.277) | .162 (.278) | .150 (.277) |

| Birth Year | .016 (.005)** | .014 (.005)** | .013 (.005)** | −.003 (.005) | −.003 (.005) | −.005 (.005) |

| Education | −.085 (.052) | −.072 (.053) | −.089 (.052) | .092 (.060) | .091 (.061) | .104 (.061) |

| Income | .019 (.009)* | .017 (.009) | .018 (.009)* | −.005 (.010) | −.004 (.011) | −.004 (.011) |

| Wave 3e | −.085 (.136) | −.051 (.136) | −.037 (.137) | .410 (.161)* | .414 (.162) | .411 (.161)* |

| Bisexualf | −.141 (.170) | −.121 (.169) | −.080 (.173) | .115 (.201) | .109 (.199) | .111 (.203) |

| Mostly Lesbianf | .023 (.123) | .023 (.125) | .053 (.124) | .015 (.137) | .013 (.140) | .057 (.138) |

| Other Sex IDf | .277 (.316) | .243 (.318) | .262 (.317) | −.325 (.379) | −.332 (.381) | −.330 (.381) |

p<.001,

p<.01,

p<.05; Reference categories:

First Wondered—Adulthood,

First Decided—Adulthood,

First Disclosed—Adulthood,

White,

Wave 1,

Only Lesbian

Birth year was positively associated with maternal support in the models for first wondered about sexual identity, first decided, and first disclosed (B=0.016, p<.01; B=0.014, p<.01; B=0.013, p<.01, respectively; Table IV) such that younger women reported higher levels of maternal support compared to older women.

DISCUSSION

These results indicate that it is not only younger age, but also earlier stage of identity development, that is associated with increased risk of lifetime suicidal ideation. This finding is consistent with the literature suggesting that earlier stages of sexual minority identity development are periods during which individuals tend to experience identity confusion and distress (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1988). According to some of the most widely recognized and accepted stage models of sexual identity development, the identity confusion period is characterized by feelings of confusion, alienation or isolation, marginalization, inner turmoil, and anxiety—feelings that are rooted in concerns about stigma (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1988) and are also known correlates of suicidal ideation (King et al. 2001; Stravynski & Boyer 2001).

Theoretical models of sexual identity development also suggest that LGB individuals become more comfortable with and confident about their sexual identity as they move through the milestones (Cass 1979; Coleman 1982; Troiden 1988). In the current study, women who were in adolescence at the earliest phase of identity development–first wondering about being a sexual minority–had heightened risk for suicidal ideation, while those who were in adolescence at the later stage of identity development did not. This suggests that where individuals are in the process of identifying as a sexual minority may be more important than age in understanding risk for suicidal ideation in this population.

Nevertheless, grappling with challenges presented in the earlier stages of sexual minority identity development may be especially difficult during early and middle adolescence when youth are more vulnerable to peer influence, fluctuations in self-esteem, and increased emotional separation from parents (Christie & Viner 2005). Because our measure of suicidal ideation asked about lifetime experiences we were unable to determine when in the life course the participant experienced suicidal ideation. However, the results suggest that the odds of suicidal ideation are greater for those who first wondered about being a sexual minority in adolescence.

Several different underlying mechanisms may explain this association. Building on previous research that found parental support to be an important factor in understanding LGB youth suicidality (Needham & Austin 2010; Ryan et al. 2009), the current study assessed the association between age at which sexual identity milestones were reached and parental support. Further, to build on the literature that suggests there are differences in LGB individuals’ relationships with their mothers and fathers (D’Augelli et al. 2005), we examined maternal and paternal support separately. Support from the mother and/or father were both independently associated with suicidal ideation, such that the risk of suicidal ideation decreased as support increased. Low parental support may, therefore, be a risk factor for suicidal ideation (Mustanski et al. 2010; Needham & Austin 2010; Ryan et al. 2009) even though it does not account for the association between younger age at first wondering about sexual identity and suicidal ideation in this study. This finding aligns with the life course framework in that the lives and behaviors of individuals cannot be fully understood unless they are considered within the context of important social relationships.

Despite the fact that the sample reported relatively high levels of maternal support during childhood the results suggest that those who first wondered about their sexual orientation at younger ages experienced more rejection from their mothers. Previous studies have found that young LGB individuals report low levels of parental support, but this is usually attributed to parent’s awareness of a child’s sexual minority identity (Needham & Austin 2010; Ryan et al. 2009). There may be different factors, such as gender nonconformity, that are associated with low support among those who wonder about their sexual identity at a young age. Another factor associated with parental support may be historical context, as assessed by birth year. Younger participants may have experienced higher levels of support because of societal changes in perceptions of sexual minorities (Becker & Todd 2014).

Similar to other studies that include African American sexual minority women (Bostwick et al. 2014), we found that African American race was protective in regard to suicidal ideation. This may be related to cultural differences in perception and acceptability of suicidal behavior; for example, there is some evidence that African-Americans overall have a more negative view of suicidality and perceive it as immoral (Chu et al. 2010).

It is also important to note the associations between suicidal ideation and childhood sexual abuse. Across all the models, women who reported childhood sexual abuse were more likely to report lifetime suicidal ideation. This may be an important risk factor to consider given evidence that lesbian and bisexual women report higher rates of childhood sexual abuse than do heterosexual women (Hughes et al. 2010). In a study conducted by Corliss and colleagues (2009) history of childhood abuse helped to explain the association between younger age at sexual identity milestones and attempted suicide. We controlled for the effect of childhood abuse but did not test whether this experience accounted for the association between younger age at milestones and suicidal ideation. We recommend that future studies more fully examine the role of childhood sexual abuse in the association between sexual identity development and suicidal ideation.

There are several limitations of the study that should be noted. First, we used non-probability sampling methods and restricted recruitment of study participants to the Chicago metropolitan area. This limits the ability to generalize the results to the larger population of sexual minority women. Second, the cross-sectional study design prevented assessment of causality. Although there was a statistically significant relationship between younger age at first wondering about sexual minority identity and suicidal ideation, it was not possible to determine whether younger age at first wondering preceded or predicted subsequent suicidal ideation. Third, the CHLEW assessed lifetime suicidal ideation, so the developmental age at which participants experienced suicidal ideation is unknown. Thus, it is unclear if developmental age at reaching sexual identity milestones was associated with suicidal ideation during the same developmental period. We were unable to assess level of seriousness of suicidal ideation (e.g., whether there was a suicide plan), which is an important element in understanding the degree of suicide risk. As other researchers have noted (Mustanski et al. 2010), levels of ideation are often inflated when other characteristics of the measure (i.e., intent, planning) are not included. Fourth, our analyses did not examine or control for sexual identity stigma, which may help explain the association between younger age at first wondering and lifetime suicidal ideation. Fifth, the assessment of the sexual identity development process was limited in that it did not assess level of distress associated with identity development milestones, which limits interpretation of the results. Finally, data were self-reported and required retrospective recall, which can lead to recall bias, particularly among the older participants who had a longer timeframe from which to recall ages at which they reached sexual identity milestones.

CONCLUSION

Despite these limitations the results suggest that younger age at the initial stage of sexual minority identity development may be a risk factor for lifetime suicidal ideation among sexual minority women. As sexual minority women reach later milestones and come to accept and integrate their sexual minority identity the risks associated with younger developmental age diminish. Thus, it appears to be the initial stage of sexual minority development more than age itself that is associated with adverse health outcomes.

Future research needs to examine different factors that may help to explain the link between younger age at the initial stage of sexual identity development and suicidal ideation. It may be that other important contextual factors, such as peer groups and stigmatizing or affirming environments, influence the association between age at milestones and mental health.

SUMMARY BOX.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

A broader understanding of risk factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicide risk among sexual minorities

Empirical evidence about developmental stages that represent periods of high risk for adverse mental health among sexual minorities

Information that can be used by nurses and other health care providers in their clinical practice to assess and intervene with youth at risk of suicide.

RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE.

Findings from this study underscore the importance of routinely assessing sexual identity and behavior, as well other risks associated with suicide, in health care settings. Nurses, because of their larger numbers and greater likelihood (compared with physicians) of working in primary care settings where youth most often seek routine care, are in a key position to identify and intervene with at-risk youth. In addition to asking youth about their romantic attractions and sexual behavior it is also important to address social support, such as whether youth feel supported by their parents, peers and other influential people. Although nurses and other providers may be reluctant to ask about childhood physical and sexual abuse, as demonstrated in this and many other studies, such experiences are clearly linked to risky behaviors and negative health outcomes. Early identification and intervention is key to interrupting a trajectory of risky behavior and negative health outcomes. Findings from this study particularly highlight the heightened vulnerability of young adolescents who are questioning their sexual identity and emphasize the importance of careful assessment of youth at this stage of development.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) AA00266 and AA13328 (T. Hughes, PI).

Footnotes

Support from the mother and father were also both separately tested as mediators and moderators of the association between younger age at first wondering and suicidal ideation. The results suggested that support from the mother and/or father did not mediate or moderate this association.

References

- Almeida J, Johnson RM, Corliss HL, Molnar BE, Azrael D. Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:1001–1014. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Normal Adolescent Development, Part 1. Vol. 57. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Washington, DC: 2011. [accessed 1 September 2015]. Available at: http://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/Facts_for_families_Pages/Normal_Adolescent_Development_Part_I_57.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. Developing adolescents: A reference for professionals. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. [accessed 1 September 2015]. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pi/families/resources/develop.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Becker AB, Todd ME. Changing perspectives? Public opinion, perceptions of discrimination and feelings toward the family. GLBT Family Studies. 2015;11:493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bilodeau BL, Renn KA. Analysis of LGBT identity development models and implications for practice. New Directions for Student Services. 2005;2005:25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick WB, Meyer I, Aranda F, Russell S, Hughes T, Birkett M, Mustanski B. Mental health and suicidality among racially/ethnically diverse sexual minority youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess D, Lee R, Tran A, van Ryn M. Effects of perceived discrimination on mental health and mental health services utilization among gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons. Journal of LGBT Health Research. 2007;3:1–14. doi: 10.1080/15574090802226626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cass VC. Homosexuality identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality. 1979;4:219–235. doi: 10.1300/J082v04n03_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzo JP, Antonucci TC, Mays VM, Cochran SD. Retrospective recall of sexual orientation identity development among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1658–1673. doi: 10.1037/a0025508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide Facts at a Glance. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [accessed 1 September 2015]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/suicide-datasheet-a.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Christie D, Viner R. Adolescent development. British Medical Journal. 2005;330:301–304. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7486.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu JP, Goldblum P, Floyd R, Bongar B. The cultural theory and model of suicide. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 2010;14:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EL. Developmental stages of the coming-out process. American Behavioral Scientist. 1982;25:469–482. [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Cochran SD, Mays VM, Greenland S, Seeman TE. Age of minority sexual orientation development and risk of childhood maltreatment and suicide attempts in women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:511–521. doi: 10.1037/a0017163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR. Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;7:433. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Grossman AH, Starks MT. Parents’ awareness of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:474–482. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings: Personal challenges and mental health problems. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:421–448. doi: 10.1007/BF00942151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Hershberger SL, Pilkington NW. Suicidality patterns and sexual orientation-related factors among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31:250–64. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.3.250.24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM. What We Got Wrong About Sexual Identity Development: Unexpected Findings from a Longitudinal Study of Young Women. In: Omoto AM, Kurtzman HS, editors. Sexual Orientation and Mental Health: Examining Identity and Development in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual People. APA Books; Washington, DC: 2006. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh DM, Moeller FG, Swann AC. Suicidal behaviors and drug abuse: Impulsivity and its assessment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:S93–S105. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. Time, human agency, and social change: Perspectives on the life course. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development. 1998;69:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason MJ, Schope R. Shifting Sands or Solid Foundation? Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Identity Formation. In: Meyer IH, Northridge ME, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities. Springer; New York, NY: 2007. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1997;44:174–199. [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems. 2002;49:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- House A, Horn EV, Coppeans C, Stepleman L. Interpersonal trauma and discriminatory events as predictors of suicidal and nonsuicidal self-injury in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender persons. Traumatology. 2011;17:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes TL, McCabe SE, Wilsnack SC, West BT, Boyd CJ. Victimization and substance use disorders in a national sample of heterosexual and sexual minority women and men. Addiction. 2010;105:2130–2140. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igartua KJ, Gill K, Montoro R. Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2003;22:15–30. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston TP, Mott JA. The reliability of self-reported age of onset of tobacco, alcohol and illicit drug use. Addiction. 2014;96:1187–1198. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.968118711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TW. Collecting Survey Data on Sensitive Topics: Sexual Behavior. In: Johnson TP, editor. Handbook of Health Survey Methods. Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RA, Schwab-Stone M, Flisher AJ, Greenwald S, Kramer RA, Goodman SH, Lahey BB, Shaffer D, Gould MS. Psychosocial and risk behavior correlates of youth suicide attempts and suicidal ideation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:837–846. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200107000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Martin CE, Pearson JL. Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:909–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JJ, Apter A, Bertolote J, Beautrais A, Currier D, Haas A, Hegerl U, Lonnqvist J, Malone K, Marusic A, Mehlum L, Patton G, Phillips M, Rutz W, Rihmer Z, Schmidtke A, Shaffer D, Silverman M, Takahashi Y, Varnik A, Wasserman D, Yip P, Hendin H. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;294:2064–2074. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Dietrich J, Schwartz S. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders and suicide attempts in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1004–1006. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.096826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needham BL, Austin EL. Sexual orientation, parental support, and health during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9533-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggle ED, Whitman JS, Olson A, Rostosky SS, Strong S. The positive aspects of being a lesbian or gay man. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2008;39:210–217. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J. Disclosure of sexual orientation and subsequent substance use and abuse among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Critical role of disclosure reactions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23:175–184. doi: 10.1037/a0014284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L. Sexual identity development among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths: Consistency and change over time. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;43:46–58. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Everett BT, Rosario M, Birkett M. Indicators of victimization and sexual orientation among adolescents: Analyses from youth risk behavior surveys. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:255–261. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123:346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzburg S. Learning that an adolescent child is gay or lesbian: The parent experience. Social Work. 2004;49:109–118. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC, Ream GL. Sex variations in the disclosure to parents of same-sex attractions. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17:429–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silenzio V, Pena JB, Duberstein PR, Cerel J, Knox KL. Sexual orientation and risk factors for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:2017–2019. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.095943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Campione-Barr N, Metzger A. Adolescent development in interpersonal and societal contexts. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:255–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stravynski A, Boyer R. Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: A population-wide study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2001;31:32–40. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.1.32.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troiden RR. Homosexual identity development. Journal of Adolescent Health Care. 1988;9:105–113. doi: 10.1016/0197-0070(88)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, Greenwald S, Hwu HG, Joyce PR, Karam EG, Lee CK, Lellouch J, Lepine JP, Newman SC, Rubio-Stipec M, Wells JE, Wickramaratne PJ, Wittchen HU, Yeh EK. Prevalence of suicide ideation and suicide attempts in nine countries. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:9–17. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health Epidemiology. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [accessed 1 September 2015]. Available at: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/epidemiology/adolescence/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]