Abstract

Alexithymia, the inability to identify and describe one’s emotional experience, is elevated in many clinical populations, and related to poor interpersonal functioning. Alexithymia is also associated with empathic deficits in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Accordingly, a better understanding of alexithymia could elucidate the nature of social-cognitive deficits transdiagnostically. We investigated alexithymia and components of empathy in relation to schizotypal and autism spectrum traits in healthy college students. Specifically, we examined higher-order components of empathic processing that involve perspective taking and other-oriented concern, which are reduced in alexithymia.

Higher-order empathic processing was inversely correlated with both schizotypal and autism spectrum traits. Bootstrapping techniques revealed that alexithymia had a significant indirect effect on the relationship between higher-order empathy and these personality traits; thus, alexithymia contributes uniquely to their relationship. These findings suggest alexithymia represents one possible mechanism for the development of empathic deficits in these populations.

These results are consistent with the perspective that awareness of one’s own emotional state may predicate a successful empathic response to another’s. This work highlights the importance of a consideration of alexithymia in elucidating the nature of empathic deficits in various clinical populations, and points to a potential point of social intervention.

Keywords: alexithymia, schizotypy, empathy, autism spectrum traits, empathy, emotion

1. Introduction

Alexithymia is characterized by impaired capacity to consciously experience emotions, resulting in the inability to identify and describe one’s emotional experience (Lane, Ahern, Schwartz, & Kaszniak, 1997); clinical levels of alexithymia are found in around 10% of the population (Salminen, Saarijärvi, Äärelä, Toikka, & Kauhanen, 1999). Alexithymia is related to diverse medical and psychological conditions (Taylor, Bagby, & Parker, 1997). Heightened levels of alexithymia have been reported in populations with autism spectrum disorders (ASD; e.g., Hill, Berthoz, & Frith, 2004), schizophrenia (e.g, van’t Wout, Aleman, Bermond, & Kahn, 2007), those high in schizophrenia-like traits (Seghers, McCleery, & Docherty, 2011), and ASD traits (Lockwood, Bird, Bridge, & Viding, 2013), leading some to argue that alexithymia contributes uniquely to social dysfunction in these disorders (Bird et al., 2010; Bird & Cook, 2013; van’t Wout, Aleman, Bermond, & Kahn, 2007).

It is not surprising that alexithymia is heightened in both autism-spectrum and schizophrenia-spectrum populations: both schizophrenia and autism are associated with vast and overlapping deficits in social cognition (see Sasson, Pinkham, Carpenter, & Belger, 2011). Continuing to elucidate the role of alexithymia in social functioning may help better clarify alexithymia as a mechanism of social deficits, across diagnostic boundaries, consistent with the aims of the Research Domain Criteria project (RDoC; see Insel et al., 2010).

Alexithymia is related to significant interpersonal difficulties (Koven, 2014; Spitzer, Siebel-Jürges, Barnow, Grabe, & Freyberger, 2005; Vanheule, Desmet, Meganck, & Bogaerts,Lamm 2007); particularly problematic is its association with decreased empathy. Empathy is a broad and multifaceted construct subject to myriad definitions, but most researchers agree that empathy requires: 1) an affective response to another person; 2) a cognitive capacity to adopt the perspective of another person; and 3) self-regulatory mechanisms that modulate inner states (see Decety & Moriguchi 2007 for review). Many self-report studies highlight the association between alexithymia and empathic deficits (Guttman & Laporte, 2002; Jonason & Krause 2013; Moriguchi et al., 2007; Silani et al. 2008; Swart, Kortekaas, & Aleman, 2009). Furthermore, imaging studies demonstrate that those high in alexithymia show abnormal neural responses during tasks designed to evoke empathy (Moriguchi et al., 2007; Silani et al., 2008).

The connection between alexithymia and empathic deficits may be explained by the “shared-network hypothesis:” this theory is based on evidence that the neural networks responsible for processing one’s own emotions are the same used to process the emotions of others. Areas of activation in the shared-network include sensory and affective components of pain processing (Singer & Lamm 2009; Singer et al., 2004): studies show that those with empathic deficits show less activation of the affective components of the shared-network while watching a loved one undergo a painful experience (Singer et al., 2004). The affective regions include the insular and anterior cingulate cortices, which could be involved in forming a subjective representation of one’s emotional experience (Lane et al., 1997): a lack of such subjective representation might lead to difficulty understanding another individual’s experience. Imaging studies have well documented that alexithymia is associated with abnormal neural activity in areas of the brain responsible for forming such a subjective experience (e.g., Singer, Critchley, & Preuschoff, 2009).

Conscious awareness of one’s own emotional state is associated with an understanding of another individual’s emotional state (Decety & Jackson, 2004; Gallup, 1998; Singer et al., 2004), so it is not surprising that alexithymia is correlated with empathic deficits; yet, the precise nature of this relationship remains unknown. Recently, Silani et al. (2008) and Bird et al. (2010) examined this complex relationship in a population characterized by both alexithymia and empathic deficits: ASD. Despite the widespread assumption that ASD is associated with decreased empathy, Silani et al. (2008) and Bird et al. (2010) found that only ASD participants with elevated levels of alexithymia demonstrate empathic deficits. This work, in addition to a growing body of literature demonstrating the relevance of alexithymia to understanding a range of emotional deficits in ASD, led Bird and Cook (2013) to propose “the alexithymia hypothesis.” They propose that the emotional symptoms of ASD are due to the high proportion of individuals with severe alexithymia in the ASD population, rather than their ASD diagnoses per se.

Bird and Cook (2013) suggest the alexithymia hypothesis might also hold true for schizophrenia. ASD and schizophrenia are both marked by vast heterogeneity of symptom profiles: alexithymia, as a transdiagnostic personality trait, might help elucidate and differentiate the nature of empathic deficits in both disorders. Understanding more about the social cognitive deficits that mark schizophrenia is critical: these deficits are greatly debilitating, and related to functional outcome (see Green, 1996). Unfortunately, there is little evidence that pharmacological treatment improves social cognition. For example, in a randomized controlled trial examining social improvement resulting from atypical antipsychotics, patients showed no improvement in affect recognition at the end of an 8-week period (Harvey, Patterson, Potter, Zhong, & Brecher, 2006). In light of these findings, as well as evidence that social cognition can be improved using behavioral interventions (see Horan, Kern, Green, & Penn, 2008), Penn and colleagues (Penn, Sanna, & Roberts, 2008) advocate for targeted psychosocial treatment programs to improve social cognition in schizophrenia. They advise against a “one-size intervention,” given the heterogeneity of the disorder. Accordingly, assessing alexithymia may inform targeted inerventions for schizophrenia and ASD.

Bird and Cook (2013) suggest the alexithymia hypothesis might also explain the empathy deficits found in schizophrenia. We aim to take the first steps towards testing this hypothesis by first examining the role of alexithymia on the empathic deficits found in individuals with schizophrenia-like traits in a healthy population. Specifically, schizotypy refers to a set of personality traits that may indicate a predisposition towards schizophrenia (Claridge, 1990; Lenzenweger, 2006; Lenzenweger, 2011). We sought to investigate the potential effect of alexithymia on the established negative correlation between schizotypy and empathy (Henry, Bailey, & Rendell, 2008; Thakkar & Park, 2010). We hypotheses that elevated alexithymia will explain this correlation.

We also aimed to investigate the role of alexithymia on the negative correlation between empathy and ASD traits in the typically developing population. Lockwood et al. (2013) found a strong correlation between ASD traits and performance on a theory of mind task, but report that alexithymia cannot explain the association. They note that their conclusions are inconsistent with results in the ASD population (Bird et al., 2010; Silani et al., 2008). We sought to extend these findings by investigating the role of alexithymia on the correlation between ASD traits and a broader and more common measure of empathy, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983).

The IRI measures four distinct subtypes of empathic processing: perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress (Davis, 1983). Alexithymia is consistently associated with decreased empathic concern and perspective taking (e.g., & Laporte, 2002; Moriguchi et al., 2007; Silani et al., 2008), thought to reflect “mature,” or higher-order, empathic processing (Guttman & Laporte 2000; Guttman & Laporte 2002). Alexithymia is also consistently correlated with normal or increased levels of personal distress (e.g., Guttman et al., 2002; Moriguchi et al., 2007; Silani et al., 2008), thought to reflect “immature,” or lower-order empathic processing (Guttman & Laporte, 2000; Guttman & Laporte, 2002; Moriguchi et al., 2007).

In a review of empathy literature, Hoffman (1976) explained the differences between these subtypes of empathy: early in development, children are unable to differentiate “self” and “others.” Thus, when observing another in distress, the child, unable to adopt the perspective of another person, experiences the distress as his or her own (Davis, 1994). Accordingly, the “personal distress” subscale of the IRI is thought to represent a “primitive,” or lower-order form of empathic response (Moriguchi et al., 2007). Conversely, the subscale “empathic concern” involves the more mature empathic response of other-oriented concern; similarly, the perspective taking subscale assesses one’s ability to step outside of the self, imagining the unique perspective of another person (Davis 1983).

The goals of the current study were to investigate the association between mature empathy and schizotypy in the general population. We hypothesized that ‘mature empathy’ (consisting of perspective taking and empathic concern) will be associated with reduced schizotypy, via an indirect relation with alexithymia. We also aimed to evaluate the established correlation between empathy and ASD traits in the general population (Gökçen, Petrides, Hudry, Frederickson, & Smillie, 2014; Wheelwright et al., 2006). We hypothesized that mature empathy will be associated with lower ASD traits via an indirect association with alexithymia.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

139 (95 female) students (Mean age = 21.94, s.d. = 1.36) were recruited from psychology courses at Vanderbilt University. Participants completed a battery of questionnaires presented online. The study protocol was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board, and all participants consented to participate prior to testing. Participants fulfilled course requirement through their participation.

2.2 Materials

The 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20; Bagby, Parker, & Taylor, 1994)

This scale consists of 20 items and measures three dimensions of the alexithymia construct: difficulty identifying feelings (DIF), difficulty describing feelings (DDF), and externally-oriented thinking (EOT). Participants are asked to what extent they agree with statements using a five-point Likert scale. Chronbach’s alpha is .87 in the present study.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1983)

The IRI is a multidimensional empathy questionnaire, comprised of the following subscales: perspective taking, fantasy, personal distress, and empathic concern. The IRI consists of 28 items, to which participants respond with a five-point Likert scale. Chronbach’s alpha is .81 in the present study.

The Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire (SPQ; Raine, 1991)

The SPQ is a 74-item self-report questionnaire. Participants respond to statements with “yes” or “no” answers. Factor analysis reveals that SPQ break down into three factors: perceptual-cognitive, interpersonal, and disorganization. These correspond respectively with the positive, negative, and disorganized factors of schizophrenia (Raine et al., 1994). Chronbach’s alpha is .94 in the present study.

The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ; Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin, & Clubley 2001)

The AQ is a 50-item questionnaire specifically designed to assess autism traits in adults with average or higher IQ. The AQ assesses five areas associated with autism and the extended phenotype: social skill, attention switching, attention to detail, communication and imagination. Participants respond using a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 4 = strongly agree). Responses are coded as zero or one, with one point awarded if a participant chooses the “autistic trait” response. The “autistic trait” is indicated by a response of strongly/slightly agree for half of the items, and slightly/strongly disagree for the other half. Chronbach’s alpha is .81 in the present study.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996)

The BDI-II is a 21-item questionnaire that assesses depressive affect and associated behavioral symptoms using a four-point Likert scale. Chronbach’s alpha is .91 in the present study.

2.3 Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS. Associations between SPQ and AQ with the IRI and its facets were tested with Spearman correlations. To confirm associations between variables of interest for assessing indirect effect (i.e., mature empathy, AQ, SPQ, and TAS-20), linear regression analysis was performed. After positive correlations were established between these variables, the mediating effect of TAS-20 was tested using Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrap mediation technique, with bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals. Finally, because of the high correlation between alexithymia and depression (Honkalampi Hintikka, Tanskanen, Lehtonen, & Viinamäki, 2000), BDI scores were entered into this model as a covariate.

3. Results

Individuals with clinically elevated levels of alexithymia (TAS-20 score greater than 60; Taylor et al., 1997) had higher AQ and SPQ scores (p < .001). Alexithymia was positively correlated with SPQ (ρ = .300, p < .001) and AQ (ρ = .503, p < .001). All three factors of SPQ were positively correlated with TAS-20 (p < .001). All five AQ subscales were also positive correlated with TAS-20 (p < .05). BDI was positively correlated with TAS-20 (ρ = .46, p < .001), replicating previous findings of correlations between alexithymia and depression. There was no significant difference in TAS-20 scores between men and women (p = .294).

All other descriptive findings are reported in Table 1. We report Spearman correlations among SPQ, AQ and IRI in Table 2. As predicted, Perspective Taking was negatively correlated with AQ and SPQ (p < .001). Empathic Concern was negatively correlated with AQ (p < .01). Personal Distress was correlated positively with AQ and SPQ (p < .001).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Alexithymia, Empathy, SPQ, and AQ:

| Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|

| TAS-20 | |

| Difficulty Describing Feelings | 13.93 (3.886) |

| Difficulty Identifying Feelings | 17.53 (5.194) |

| Externally Oriented Thinking | 18.20 (4.323) |

| TAS-20 Total | 49.67 (11.001) |

| IRI | |

| Perspective Taking | 18.01 (4.216) |

| Fantasy | 18.22 (4.779) |

| Empathic Concern | 19.83 (3.625) |

| Personal Distress | 12.42 (4.587) |

| Mature Empathy | 37.83 (6.916) |

| SPQ | |

| SPQ-Total | 21.36 (12.274) |

| SPQ-Positive | 7.80 (6.20) |

| SPQ-Negative | 9.46 (6.54) |

| SPQ-Disorganized | 6.09 (3.83) |

| AQ | |

| AQ-Total | 17.69 (5.799) |

| Communication | 2.59 (1.95) |

| Social Skill | 2.57 (1.80) |

| Imagination | 2.22 (1.53) |

| Attention to Detail | 5.42 (2.45) |

| Attention Switching | 4.89 (1.97) |

Table 2.

Spearman correlations between IRI, SPQ, and AQ.

| r | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| AQ | SPQ | |

| IRI | ||

| Perspective Taking | −.415*** | −.239** |

| Fantasy | .007 | .208* |

| Empathic Concern | −.226** | −.078 |

| Personal Distress | .265** | .311*** |

| Mature Empathy Composite | −.373*** | −.185* |

p < .01

p < .05

p < .001

In order to assess for “mature empathy (ME),” we created a composite variable comprised of “empathic concern” and “perspective taking.” This variable is consistent with conceptualizations of these two variables as aspects of mature empathy (Guttman & Laporte 2002), consistent with previous IRI analysis in this literature (i.e., Silani et al., 2008), and in line with recommendations for interpreting IRI data (i.e. avoiding summation of a “total IRI” score; D’Orazio, 2004). Both AQ (p < .001) and SPQ (p < .01) were negatively correlated with mature empathy (see table 2).

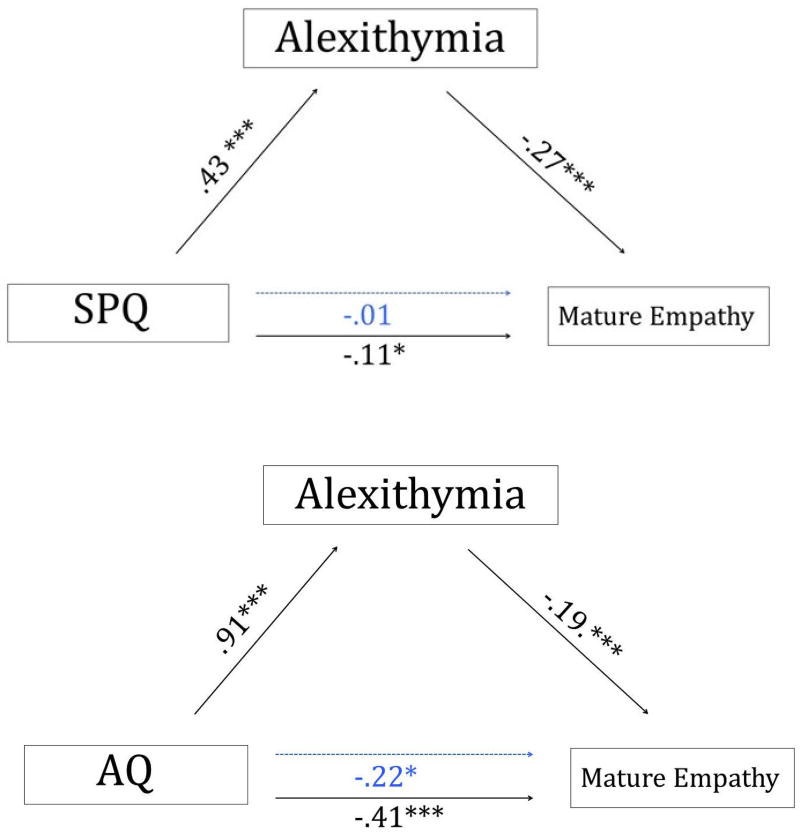

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess each component of the proposed model (see Figure 1). Mature empathy was negatively associated with alexithymia (B = −.19, t(136) = .06, p < .001), SPQ (B = −.11, t(125) = .05, p < .001) and AQ (B = −.41, t(136) = .10, p < .001). Alexithymia was positively associated with SPQ (B = .43, t(125) = .07, p < .001) and AQ (B = .91, t(136) = .14, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Results of bootstrap mediation analysis. Values depict unstandardized Beta weights. Solid lines represent direct paths between variables; dotted lines represent paths in which TAS-20 score is entered as a mediator. Alexithymia has a significant indirect effect on the relationship between SPQ and AQ on mature empathy. A significant direct effect of AQ on mature empathy remains after accounting for alexithymia. *p< .05; **p<.01; **p<.001

Because these regressions were significant, the indirect effect of alexithymia was tested using bootstrapping method (see Table 3). Alexithymia had a significant indirect effect on the association between mature empathy and SPQ (B = −.38, CI = −.56 to −.23). There was no remaining effect of SPQ on mature empathy after accounting for alexithymia. Alexithymia also had a significant indirect effect on the association between mature empathy and AQ (B = −.18, CI = −.18 to −.08); however, a direct effect of SPQ and mature empathy remained (B = −.23, t(136) = −.11, p < .05).

Table 3.

Mediation of the relationship between AQ and SPQ with mature empathy by TAS-20

| Questionnaire | Point Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | Direct Effect of ME (t) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AQ | −.1392 | [−.2141, −.0762] | −2.17* |

| SPQ | −.3772 | [−.5553, −.2320] | 0.17 |

Note: AQ = Autism Spectrum Quotient; SPQ = Schizotypal Personality Questionnaire; TAS-20 = 20-Item Toronto Alexithymia Scale; ME = mature empathy;

p < .05

Additional analyses considered the relationship between AQ and SPQ with the individual components of the mature empathy composite: perspective taking (PT) and empathic concern (EC). The indirect effect analyses remained significant in all analyses: Alexithymia had a significant indirect effect on the association between SPQ and EC (B = .05; CI = −.08 to −.03) and PT (B = .66, CI = −.103 to −.035). Alexithymia also had a significant indirect effect on the association between AQ and EC (B = .10; CI = −.17 to −.04) and PT (B = .08; CI = −.15 to −.02). All indirect effect analyses remained significant when controlling for BDI.

4. Discussion

Alexithymia is a personality trait marked by the reduced ability to consciously experience, label and describe one’s emotional state. It is interpersonally problematic, particularly as it is related to deficits in empathic processing. It may be that subjective representation of one’s own emotional state is necessary for the formation of empathic reactions to another (Decety & Jackson, 2004; Singer et al., 2009). Thus, alexithymia may render empathizing with another person nearly impossible.

The current study takes the first steps towards investigating “the alexithymia hypothesis” (Bird & Cook, 2013) in schizophrenia. Replicating previous literature (e.g., Thakkar & Park, 2010), we found strong negative correlations between schizotypy and aspects of higher-order empathy. When controlling for alexithymia, this correlation became nonsignificant. These findings are helpful for understanding the empathic deficits found in individuals with schizophrenia-like traits. Raine (2006) points out the value of elucidating the mechanisms underlying schizotypal personality traits for understanding schizophrenia, as well as informing the development of effective preventions that ameliorate symptomology.

The current study supports “the alexithymia hypothesis” in ASD traits. We replicate previous literature demonstrating negative correlations between ASD traits and empathic processing (e.g., Wheelwright et al., 2006). Although this correlation remains significant after accounting for alexithymia, a significant indirect effect of alexithymia emerges for perspective taking and empathic concern. These findings diverge somewhat from those of Lockwood et al. (2013), who conclude alexithymia does not explain reduced cognitive perspective-taking found in those with elevated ASD traits. Lockwood et al. (2013) utilized laboratory tasks whereas the current study utilized self-report measures; thus, directly comparing the two sets of findings is difficult. Nevertheless, both sets of findings highlight the potential role of alexithymia on empathic processing, particularly related to the affective components of empathy. The topic certainly warrants continued investigation to elucidate the exact nature of this relationship. The present findings shed light on the social cognitive difficulties present in those with elevated ASD traits (e.g., Gökçen et al., 2014), and have implications for understanding empathic deficits in ASD, particularly as ASD and sub-clinical ASD traits are thought to lie on the same continuum (Robinson et al., 2011).

Elucidating the role of alexithymia on empathic deficits has important implications for intervention (see Sasson et al. 2011). A recent review of intervention studies assessing alexithymia concluded the construct is malleable and responsive to psychological intervention (Cameron, Ogrodniczuk, & Hadjipavlou, 2014). For example, in an intensive psychiatric outpatient program, Ogrodniczuk, Sochting, Piper & Joyce (2011) found that changes in alexithymia after a 15-week intervention were correlated with improvement in interpersonal symptoms, and furthermore, that this improvement maintained over a 3-month follow-up. Ideal treatment for disorders with heterogeneous symptom profiles, like ASD and schizophrenia, may entail targeted psychosocial interventions (Penn et al., 2008). Further, given the overlap in ASD and schizophrenia, some have advocated for the benefit of developing shared interventions (Russell-Smith, Maybery, & Bayliss, 2011). Alexithymia may represent a fruitful target of intervention to improve interpersonal functioning transdiagnostically.

The secondary aim of the current study was to investigate the pattern of deficits in “mature empathy” consistently found in those with elevated alexithymia. As hypothesized, schizotypy and ASD traits were negatively correlated with aspects of mature empathy, and positively correlated with “personal distress.” Consistent with previous findings, this suggests that whereas alexithymia is marked by reduced ability to engage in higher-order empathic processes, lower-level personal discomfort in the face of another’s adversity remains intact.

4.1 Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study does not allow for assessment of the causal relationship between mature empathy, alexithymia, and AQ and SPQ; thus, the pattern of results suggests mediation, but cannot confirm the direction of the relationship between empathy and alexithymia. Currently, alexithymia is assessed using self-report or interview assessments. Given that ASD traits and schizotypy are associated with reduced insight, it may be problematic to rely on such self-report methods. Future work would benefit from implementation of an objective measure of alexithymia, as well as an experimental method of assessing empathy.

4.2 Conclusions

The current study demonstrates a positive correlation between alexithymia and schizotypy and ASD traits in the healthy population. The results suggest that alexithymia represents a possible mechanism for the presence of empathic deficits; particularly, aspects of higher-order empathizing that involve taking the perspective of another person. This work is consistent with findings from the ASD literature, and lays the groundwork for future investigations of alexithymia as a unique contributor to empathic deficits in schizophrenia.

Highlights.

Schizotypal and autism traits were associated with increased alexithymia

Schizotypal and autism traits were associated with abnormalities in empathy

Alexithymia contributes uniquely to empathic deficits in these populations

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the comments and advice of Joel Peterman on earlier drafts of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by an NIMH Training Grant (T32 MH018921) and an NICHD Grant P30 HD15052 to the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center for Research on Human Development. Additionally, data was stored and managed using REDCap, which is funded by an NIH grant UL1 TR000445 from NCATS/NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bagby RM, Parker JDA, Taylor GJ. The twenty-item Toronto alexithymia scale: I. item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1994;38(1):23–32. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001;31(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of personality assessment. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, Silani G, Brindley R, White S, Frith U, Singer T. Empathic brain responses in insula are modulated by levels of alexithymia but not autism. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2010;133(5):1515–1525. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, Cook R. Mixed emotions: the contribution of alexithymia to the emotional symptoms of autism. Translational psychiatry. 2013;3(7):e285. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron K, Ogrodniczuk J, Hadjipavlou G. Changes in Alexithymia Following Psychological Intervention: A Review. Harvard review of psychiatry. 2014;22(3):162–178. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claridge G. Reconstructing schizophrenia. Taylor & Frances/Routledge; Florence, KY: 1990. Can a disease model of schizophrenia survive? pp. 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- D'Orazio DM. Letter to the Editor. Sexual abuse: a journal of research and treatment. 2004;16(2):173–174. doi: 10.1177/107906320401600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Empathy: A social psychological approach. Westview Press; Boulder, CO: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Jackson PL. The functional architecture of human empathy. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews. 2004;3(2):406–412. doi: 10.1177/1534582304267187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Moriguchi Y. The empathic brain and its dysfunction in psychiatric populations: Implications for intervention across different clinical conditions. BioPsychoSocial Medicine. 2007;1(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1751-0759-1-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup GG., Jr Self-awareness and the evolution of social intelligence. Behavioural Processes. 1998;42(2–3):239–247. doi: 10.1016/s0376-6357(97)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gökçen E, Petrides KV, Hudry K, Frederickson N, Smillie LD. Sub-threshold autism traits: The role of trait emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility. British Journal of Psychology. 2014;105(2):187–199. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green MF. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? The American journal of psychiatry. 1996;153(3):321–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman HA, Laporte L. Empathy in Families of Women with Borderline Personality Disorder, Anorexia Nervosa, and a Control Group. Family process. 2000;39(3):345–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman HA, Laporte L. Alexithymia, empathy, and psychological symptoms in a family context. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2002;43(6):448–455. doi: 10.1053/comp.2002.35905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P, Patterson T, Potter L, Zhong K, Brecher M. Improvement in social competence with short-term atypical antipsychotic treatment: a randomized, double-blind comparison of quetiapine versus risperidone for social competence, social cognition, and neuropsychological functioning. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(11):1918–1925. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.11.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Bailey PE, Rendell PG. Empathy, social functioning and schizotypy. Psychiatry Research. 2008;160(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EL, Berthoz S, Frith U. Brief report: Cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34(2):229–235. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022613.41399.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy, role taking, guilt, and development of altruistic motives. Garland Publishing; New York, NY: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Honkalampi K, Hintikka J, Tanskanen A, Lehtonen J, Viinamäki H. Depression is strongly associated with alexithymia in the general population. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2000;48(1):99–104. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horan WP, Kern RS, Green MF, Penn DL. Social cognition training for individuals with schizophrenia: emerging evidence. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2008;11(3):205–252. [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Wang P. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(7):748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonason PK, Krause L. The emotional deficits associated with the dark triad traits: Cognitive empathy, affective empathy, and alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55(5):532–537. [Google Scholar]

- Koven NS. Abnormal valence differentiation in alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;68:102–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lane RD, Ahern GL, Schwartz GE, Kaszniak AW. Is alexithymia the emotional equivalent of blindsight? Biological Psychiatry. 1997;42(9):834–844. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF. Schizotypy, an organizing framework for schizophrenia research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15(4):162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzenweger MF. Schizotypy and schizophrenia: The view from experimental psychopathology. Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood PL, Bird G, Bridge M, Viding E. Dissecting empathy: high levels of psychopathic and autistic traits are characterized by difficulties in different social information processing domains. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi Y, Decety J, Ohnishi T, Maeda M, Mori T, Nemoto K, Komaki G. Empathy and judging other's pain: An fMRI study of alexithymia. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17(9):2223–2234. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk JS, Sochting I, Piper WE, Joyce AS. A naturalistic study of alexithymia among psychiatric outpatients treated in an integrated group therapy program. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2012;85(3):278–291. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.2011.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn DL, Sanna LJ, Roberts DL. Social cognition in schizophrenia: an overview. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2008;34(3):408–411. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. The SPQ: A scale for the assessment of schizotypal personality based on DSM-III-R criteria. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1991;17(4):555–564. doi: 10.1093/schbul/17.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A. Schizotypal personality: neurodevelopmental and psychosocial trajectories. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2006;2:291–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A, Reynolds C, Lencz T, Scerbo A, Triphon N, Kim D. Cognitive-perceptual, interpersonal, and disorganized features of schizotypal personality. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1994;20(1):191–201. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson EB, Koenen KC, McCormick MC, Munir K, Hallett V, Happé F, Ronald A. Evidence that autistic traits show the same etiology in the general population and at the quantitative extremes (5%, 2.5%, and 1%) Archives of general psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1113–1121. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell-Smith SN, Maybery MT, Bayliss DM. Relationships between autistic-like and schizotypy traits: An analysis using the Autism Spectrum Quotient and Oxford-Liverpool Inventory of Feelings and Experiences. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;51(2):128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Salminen JK, Saarijärvi S, Äärelä E, Toikka T, Kauhanen J. Prevalence of alexithymia and its association with sociodemographic variables in the general population of Finland. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999;46(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson NJ, Pinkham AE, Carpenter KL, Belger A. The benefit of directly comparing autism and schizophrenia for revealing mechanisms of social cognitive impairment. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders. 2011;3(2):87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11689-010-9068-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghers JP, McCleery A, Docherty NM. Schizotypy, alexithymia, and socioemotional outcomes. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199(2):117–121. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182083bc4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silani G, Bird G, Brindley R, Singer T, Frith C, Frith U. Levels of emotional awareness and autism: An fMRI study. Social Neuroscience. 2008;3(2):97–112. doi: 10.1080/17470910701577020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Critchley HD, Preuschoff K. A common role of insula in feelings, empathy and uncertainty. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2009;13(8):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Lamm C. The social neuroscience of empathy. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1156(1):81–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1157–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1093535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer C, Siebel-Jürges U, Barnow S, Grabe HJ, Freyberger HJ. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2005;74(4):240–246. doi: 10.1159/000085148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swart M, Kortekaas R, Aleman A. Dealing with Feelings: Characterization of Trait Alexithymia on Emotion Regulation Strategies and Cognitive-Emotional Processing. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JDA. Disorders of affect regulation: Alexithymia in medical and psychiatric illness. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar KN, Park S. Empathy, schizotypy, and visuospatial transformations. Cognitive neuropsychiatry. 2010;15(5):477–500. doi: 10.1080/13546801003711350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van't Wout M, Aleman A, Bermond B, Kahn RS. No words for feelings: alexithymia in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2007;48(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheule S, Desmet M, Meganck R, Bogaerts S. Alexithymia and interpersonal problems. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63(1):109–117. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelwright S, Baron-Cohen S, Goldenfeld N, Delaney J, Fine D, Smith R, Wakabayashi A. Predicting autism spectrum quotient (AQ) from the systemizing quotient-revised (SQ-R) and empathy quotient (EQ) Brain research. 2006;1079(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]