Abstract

For a patient with metastatic colorectal cancer there are limited clinical op-tions aside from chemotherapy. Unfortunately, the development of new chemot-herapeutics is a long and costly process. New methods are needed to identify promising drug candidates earlier in the drug development process. Most chemo-therapies are administered to patients in combinations. Here, an in vitro platform is used to assess the penetration and metabolism of combination chemotherapies in three-dimensional colon cancer cell cultures, or spheroids. Colon carcinoma HCT 116 cells were cultured and grown into three-dimensional cell culture spheroids. These spheroids were then dosed with a common combination chemotherapy, FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5-fluorouracil, and irinotecan) in a 3D printed fluidic device. This fluidic device allows for the dynamic treatment of spheroids across a semipermeable membrane. Following dosing, the spheroids were harvested for quantitative proteomic profiling to examine the effects of the combination chemotherapy on the colon cancer cells. Spheroids were also imaged to assess the spatial distribution of administered chemotherapeutics and metabolites with MALDI-Imaging Mass Spectrometry. Following treatment, we observed penetration of folinic acid to the core of spheroids and metabolism of the drug in the outer proliferating region of the spheroid. Proteomic changes identified included an enrichment of several cancer associated pathways. This innovative dosing device, along with the proteomic evaluation with iTRAQ-MS/MS, provides a robust platform that could have a transformative impact on the pre-clinical evaluation of drug candidates. This system is a high-throughput and cost effective approach to examine novel drugs and drug combinations prior to animal testing.

Introduction

The use of in vitro methods is vital to the drug development process to screen drug efficacy prior to animal models.1–4 One well-established model system for in vitro research is three-dimensional cell cultures, or spheroids.5–7 Spheroids can be formed by manipulating growth conditions for a number of immortalized cell lines.8 The use of spheroids in research studies reduces ethical con-cerns and allows for substantial experimental flexibility compared to animal mod-els.8 Spheroids recapitulate aspects of in vivo tumors, such as gene expression patterns, cell signaling and cell morphology.5,9,10 Spheroids also display chemical gradients of oxygen and nutrients, giving rise to radially symmetric pathophysiological layers.11–13 These layers include an inner necrotic core, a middle quiescent zone, and an outer proliferative region.14 These regions mimic the layers in an avascular tumor, making spheroids a viable model system to investigate cancer biology.1,8,15–19

Spheroids have been used to study angiogenesis20, the tumor microenvironment21,22 and immune cell response23 for various types of cancer. Spheroids are also commonly used to investigate chemotherapeutic penetration and metabolism into cancer cells.24–27 After treatment of spheroids with a drug of interest, the penetration and metabolism of chemotherapeutics and their metabolites can be determined in a spatially-defined manner. Various methods have been used to assess drug penetration into spheroids including autoradiography28, fluorescence imaging29, positron emission tomography30, magnetic resonance imaging31 and single-probe imaging.32 These methods, although useful, require radioisotopes or imaging probes that may alter the distribution of the drug of interest in spheroids.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging (MALDI-MSI) is an alternative imaging method that does not require the addition of probes or labels into the biological system.33–35 For MALDI-MSI experiments, spheroids are gelatin embedded, frozen, cryosectioned and then thaw mounted on conductive glass slides.33,36 A MALDI matrix is applied to the slides and the slides are inserted into the instrument for analysis. The MALDI laser is rastered across the sample in a grid-like pattern. Once the laser is rastered across the entire sample surface, an ordered array of mass spectra is obtained. Ion density maps can be created by selecting one or more m/z values in the combined mass spectrum.

Late stage colorectal cancer is commonly treated clinically with combina-tion chemotherapy.37 One common chemotherapy regime given to patients is FOLFIRI (FOL: Folinic acid (Leucovorin); F: 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU); IRI: Irinotecan). The FOLFIRI treatment regime is given to a patient over a 24 to 48-hour period and administered every 2 weeks for a total of 12 weeks. Folinic Acid works in combination with 5-FU to inhibit thymidylate synthase. A 5-FU metabo-lite, 5-fluorouridine triphosphate is incorporated into RNA and disrupts protein translation. Folinic acid, a folate analog, stabilizes a trimeric inhibitory complex formed by thymidylate synthase, 5-fluorouridine triphosphate and methyl tetrahy-drofolate. The combination of 5-FU and folinic acid improves tumor response rates and overall survival compared to 5-fU treatment alone.38,39 Irinotecan is a prodrug that is metabolized to its active metabolite, SN-38. SN-38 binds to topoisomerase I and induces cell death by interfering with DNA synthesis and repair processes. Irinotecan is primarily metabolized in the liver in vivo and also metabolized by colon-derived three-dimensional cell cultures.19,24,25

In this study, spheroids were dosed with the FOLFIRI treatment regime utilizing a 3D printed fluidic device previously described in the literature.24,40,41 Briefly, the device consists of 6 flow channels with circular openings on the top of each channel. These openings are printed to accommodate cell culture inserts with a semi-permeable membrane. The membrane inserts, containing spheroids, are inserted on-top of the flow channel to allow for the diffusion of small mole-cules into and out of the flow channel. This device provides a realistic model for dosing with the incorporation of dynamic flow and can be used for the generation of pharmacokinetic curves mimicking the loading and clearance of chemotherapeutics used in vivo.

In this study, we first examined the penetration and localization of folinic acid and irinotecan into dynamically dosed spheroids. We further investigated the global proteomic changes resulting from combination chemotherapy treatment using isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ). Previous stud-ies in our lab examined the effect of a single chemotherapeutic, 5-FU, on the co-lon cancer proteome between two metastatic colon carcinoma cell lines in two-dimensional cell culture.42 This study expands on those findings with the use of 3-dimensional cell culture, the addition of folinic acid and irinotecan and the use of a more realistic dynamic dosing device. Quantitative proteomic analysis complemented with MALDI-MSI provides a realistic examination of the effects of combination chemotherapeutics on colon cancer cells. This platform has the ability to examine the efficacy of novel drugs and drug combinations, which can help to identify promising chemotherapies in a more timely fashion.

Experimental Section

Growth of 3D Cell Culture Spheroids

The human colon carcinoma cell line HCT 116 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The provider guaranteed authentication of the cell line by cytogenetic analysis and the cell line was validated by Short Tandem Repeat Sequencing in 2016. Cells were used within 3 months after resuscitation of frozen aliquots thawed from liquid nitrogen. Cells were cultured as adherent cells in McCoy’s 5A cell culture medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The medium was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2.5 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% carbon dioxide.

HCT 116 spheroids were formed following established protocols.43 Briefly, 6,000 cells were seeded into the inner 60 wells of an ultra-low attachment 96 well plate (Corning, Tewksbury, MA, USA). Following 3 days in culture, half-volume medium changes were performed every 48 hours. The spheroids were harvested for treatment at days 12–14, when the diameter of the spheroids reached ~1 mm.44 At a size of 1 mm, spheroids begin to develop central necrosis and develop regions of hypoxia similar to an in vivo tumor. 45

Preparation of Drug Solutions

Irinotecan hydrochloride, folinic acid calcium salt hydrate, and 5-fluorouracil were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). All drugs were prepared as 1 mM stock solutions by dissolving the compound in nanoPure wa-ter. The 1 mM solution was further diluted in medium to a final concentration of 20.6 μM, 11.3 μM and 68.5 μM for irinotecan, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil respectively.

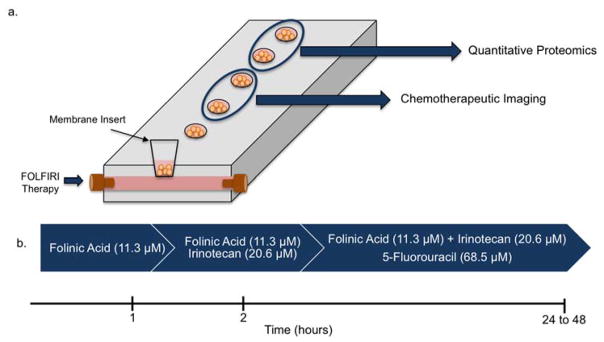

in vitro Dosing Platform

Spheroids were dosed with the use of a 3D printed device as discussed previously.24 Briefly, spheroids were placed into membrane inserts (0.4 μm pore diameter; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) that fit into the 3D printed device. These inserts rest on top of a flow channel, which allows for the diffusion of small molecules. The device has 6 identical channels, which can accommodate 6 experiments at once and allows for 36 biological replicates in a single run. The spheroids were dosed using the clinical timescale for the FOLFIRI treatment regime over a 24 hour period, depicted in Figure 1.46,47 First, 11.3 μM folinic acid was added to the inserts that housed the spheroids within the 3D printed device for the first hour. At the start of the second hour, 20.6 μM irinotecan was manually added to the inserts. At the start of the third hour, 68.5 μM 5-fluorouracil was manually added to the inserts and flowed through the 3D printed device. The top of the inserts was covered to prevent evaporation.

Figure 1.

3D printed fluidic device and FOLFIRI dosing schedule. (a) Cartoon schematic of 3D printed fluidic device and chemical readout following dosing. (b) Time course and drugs for FOLFIRI treatment. Spheroids were dosed for 24 hours consisting of folinic acid for the first hour, irinotecan for the second hour and 5-fluorouracil for the remaining 22 to 46 hours.

Small Molecule Extraction and 5-Fluorouracil Quantitation

The following concentrations for 5-fluorouracil were prepared in duplicate: 0, 2.5, 5.0, 12.5, and 25.0 μM with a final 5-chlorouracil concentration of 2 μM. A calibration curve (S-Figure 2) was generated by plotting the maximum intensity of 5-fluoruracil over the maximum intensity of 5-chlorouracil versus the concentration of 5-fluorouracil in each sample. The linearity was determined by linear regression analysis.

Following dosing, spheroids were centrifuged and washed twice with PBS. The weight of the homogenized spheroids was measured on a balance and recorded. Small molecules were extracted by adding 500 μL of extraction solution (0.01 M HCl:methanol, 2:3, v/v) containing 2 μM 5-chlorouracil. Cellular extracts were vortexed, sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 15 minutes at 4 °C. The supernatants were transferred to clean tubes and evaporated to dryness. Dried extracts were resuspended by vortexing in 100 μL of 0.1 % formic acid in water.

A 2 μL sample was injected onto a C18 reverse phase column (100 μm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) (Waters Corporation) with an isocratic mobile phase of 0.1 % formic acid in water and methanol (97:3) at a flow rate of 1 μL/min. Samples were then analyzed in negative mode on a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany) using targeted single ion monitoring (SIM). The targeted SIM scans for quantification were ac-quired with an automatic gain control target of 1.0e5, resolution of 70,000, and maximum ion transfer time of 100 ms. SIM targets included 5-fluorouracil (m/z 129.08) and the internal standard 5-chlorouracil (m/z 145.53). The response ratio of 5-fluorouracil to 5-chlorouracil was calculated and the sample concentration was determined with the generated calibration curve. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

MALDI-MSI of Spheroids

Following treatment, spheroids were washed with phosphate buffered saline. Spheroids were transferred to a gelatin-coated 24-well plate. Warm gelatin (175 mg/ml in water) was placed on top of the spheroids and flash frozen at −80 °C. Spheroids were sliced into 14 μm thick sections using a cryostat at −29 °C. These slices were thaw mounted onto an indium tin oxide coated glass slide (Delta Technologies, Loveland, CO, USA). The MALDI matrix 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 60:40 ACN/H20 with 0.2 % TFA (EMD, Billerica, MA, USA). The final concentration of the DHB solution was 30 mg/ml. The matrix solution was filtered through a 0.22 μm filter and applied using a TM-Sprayer (HTX Technologies, Carrboro, NC, USA). Heated sheath gas (N2, 10 psi) was used to deliver the matrix solution on the prepared slides. The temperature was 70°C and the solvent pump flow rate was 0.1 mL/min. Matrix was applied in a crisscross pattern 4 times. The sample was dried in a desiccator for 1 hour.

MALDI-MSI spectra were acquired using an ultrafleXtreme MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Mass spectra were acquired in reflectron positive ion mode with 800 laser shots per spot. The laser spot size was set to 35 μm. The laser was set at 69% with a sampling fre-quency of 2 kHz. Mass spectra were acquired in a mass range of 300–1000 m/z. Images were processed with flexImaging 4.1 software (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) to generate ion maps with a semiquantitative color scale bar normalized to total ion count.

Quantitative Proteomics Sample Preparation

Following dosing, spheroids were harvested with Lysis-M reagent kit (Roche Di-agnostics, Indianapolis, IN) with 1X Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche). A BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) with bovine albu-min standards (Thermo Scientific, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) was used to deter-mine total protein concentration of each sample. A total of 300 μg of protein from each lysate was added to six volumes of cold acetone and allowed to pre-cipitate for 12 h at a temperature of −20 °C. Supernatants were then removed and pellets were washed with 500 μL of cold acetone and allowed to air-dry for 5 minutes. Pellets were resuspended in 50 μL of 8 M urea and quantified using a BCA assay. 50 μg of each sample were then taken to continue sam-ple preparation.

Cysteine bonds were reduced with 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 20 minutes at 56 °C. Reduced cysteine bonds were alkylated with 14 mM iodoacetamide (IAA) for 20 minutes in the dark at room temperature. Another 5 mM aliquot of DTT was added to quench the alkylation reaction. 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.2) was added to the samples to dilute the urea concentration to 1.5 M. Samples were then di-gested overnight at 37 °C with trypsin in 1 mM CaCl2. Peptides were desalted with 10mg Oasis HLB cartridges (Waters) and lyophilized. Each sample was resuspended in 1M TEAB and labeled with four labels from an iTRAQ 8-plex reagents kit (AB Sciex cat 4390812) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Each vial of label was split and used to label 50 μg of peptides in Experiment 1 and 50 μg of peptides in Experiment 2. The four conditions in each experiment were combined into a single sample, resulting in one Experiment 1 sample and one Experiment 2 sample. Each sample was then vacuum-dried and desalted with 50 mg C18 Sep-Paks. The samples were then resuspended in 120 μL of Buffer A (10 mM KH2PO4 in 20% ACN, pH 2.85) for strong cation exchange (SCX) liquid chromatography fractionation.

SCX Fractionation

SCX fractionation was performed on the iTRAQ-labeled samples using a Waters Alliance HPLC System. 100 μL of sample was loaded onto an SCX guard column (2.1 mm i.d. × 50 mm length, 5 μM particles, Agilent Technologies). A 60-minute run with a mobile phase gradient was generated using Buffer A and Buffer B (1 M KCl in Buffer A, pH 2.85) at a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. The first 10 minutes of the method consisted of washing the column with 100% Buffer A to remove excess iTRAQ reagent. Following the wash, peptides were fractionated by a linear gradient from 100% Buffer A to 100% Buffer B. Factions were col-lected every minute for a total of 31 fractions.

Peptide Desalting

SCX fractions were then dried down and resuspended in 60 μL of 0.1 % for-mic acid (FA) in H2O. 20 μL of the samples were then desalted with C18 ZipTips (Milipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The desalted peptide volume was dried and resuspended in 0.1 % FA in HPLC grade water.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Sample separation was performed with a nanoACQUITY Ultra Performance LC (UPLC) system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) coupled to a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Peptides were loaded onto a BEH C18 reverse phase column (100 μm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm particle size) (Waters Corporation) and separated with a binary solvent system consisting of 0.1% FA in water (A) and 0.1% FA in ACN (B). Peptide elu-tion occurred over a linear gradient going from 6–50% B in 48 minutes, followed by a wash at 85% B for 10 minutes and then equilibrated with 2% B for 12 min-utes. The flow rate was kept at 800 nL/min. The Q-Exactive nanoelectrospray ion source was operated at a 1.8 kV and the ion-transfer tube was maintained at 280°C. Full MS scans were acquired with a resolution of 70,000 and an auto-matic gain control (AGC) of 1 × 106 and a maximum fill time of 250 ms. Full MS scans were acquired with an m/z range of 350–2000. For MS/MS scans, a top 12 method was used. The intensity threshold for selection was set to 1 × 105. Parent ions were fragmented with a normalized collision energy of 31%. The AGC value for MS/MS was set to a target value of 1 × 106 with a maximum fill time of 120 ms. All samples were run in duplicate, including the control (flipped) labeling samples.

Data Analysis

The .raw files acquired using the Q-Exactive were analyzed with MaxQuant soft-ware (version 1.5.8.3). All files were searched against the Uniprot human refer-ence database (Version 2012_05 updated on 05/2012) containing 88, 266 pro-tein sequences including common contaminants using the Andromeda search engine. Digestion mode was set to trypsin with a maximum of 2 missed cleav-ages. Variable modifications included N-terminal protein acetylation, methionine oxidation, N-terminal glutamine deamination, and iTRAQ 8-plex labels on protein N-terminal and tyrosine. Carbamidomethylation of cysteine was set as a fixed modification. Peptides with a minimum length of 7 amino acids were considered. The peptide and protein false discovery rate (FDR) was set to 1%. The first search peptide mass tolerance was set to 20 ppm and the main search peptide tolerance was set to 4.5 ppm. Product ions were searched with a mass tolerance of 20 ppm. Protein groups were determined by identified proteins that could be reconstructed from a set of peptides. Protein groups marked as contaminant or reverse were discarded.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis of MaxQuant search data was performed using ProteoSign48 according to author instructions. Instructions for analysis can be found at http://bioinformatics.med.uoc.gr/ProteoSign/.

Results and Discussion

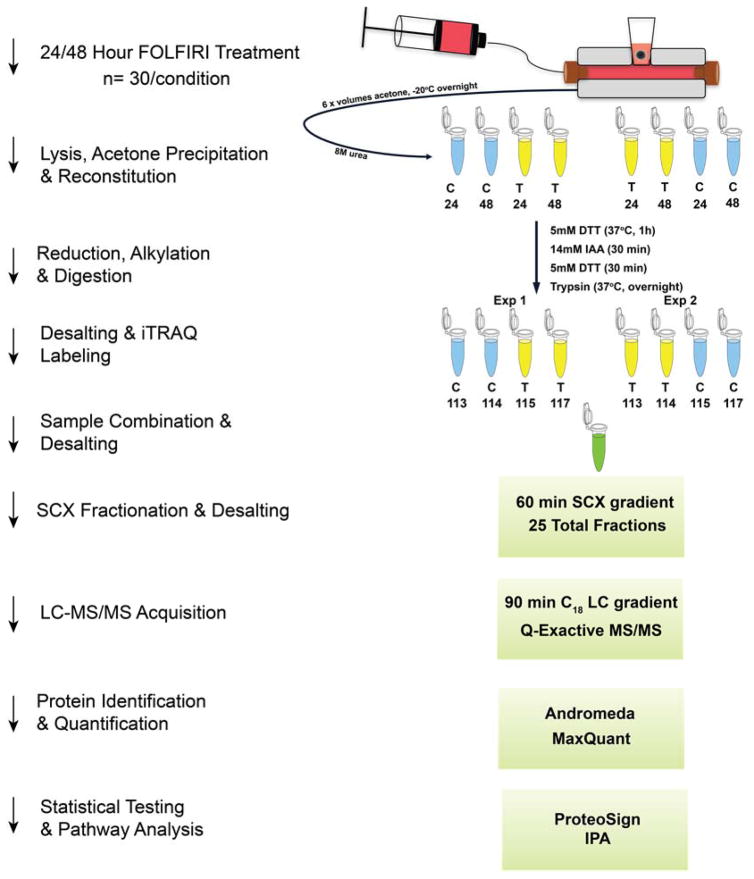

HCT 116 colon carcinoma cells were cultured into three-dimensional cell cultures and dosed with the FOLFIRI (Figure 1) combination chemotherapy using a 3D printed fluidic device. Following dosing, spheroids were analyzed for drug penetration and quantitative proteomic changes. The localization of irinotecan, folinic acid and a folinic acid metabolite were imaged via MALDI-MSI. 5-Fluorouracil was quantified in spheroids using a small molecule extraction and LC-MS analysis. iTRAQ (Figure 2) was used to quantify proteomic changes induced by the FOLFIRI treatment.

Figure 2.

iTRAQ overview and workflow. Four labels from an iTRAQ 8-plex reagent kit were used to conduct our experiments in biological duplicate. Each experiment of four labels was combined and fractionated using strong cation exchange. Samples were then analyzed using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer and searched using MaxQuant software. Statistical testing and pathway analysis was then performed on the identified proteins.

MALDI-MSI Analysis of Chemotherapeutics

Complete penetration of chemotherapeutics into tumors is necessary for optimal therapeutic effect. Tumors contain multiple cell types and it is essential for the drugs to reach each of these sub-populations for maximal drug potency.1 The spheroid model system used in this study shows three distinct cell populations that are similar to an in vivo tumor.5,9,10 By using MALDI-MSI, the localization of chemotherapeutics within the three distinct spheroid regions can be mapped.

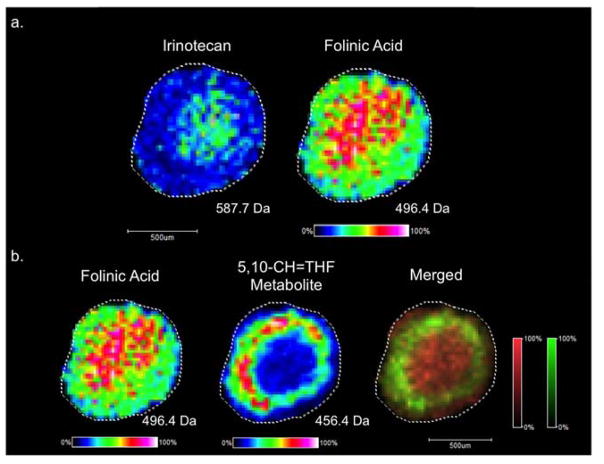

MALDI-MSI was performed on colon carcinoma HCT 116 spheroids after dynamic dosing with the FOLFIRI combination therapy. Folinic acid, irinotecan, and a folinic acid metabolite were detected in tumor spheroids (Figure 3). Previously, our lab characterized the penetration of irinotecan and its metabolism in spheroids after static chemotherapy treatment.19,24,25 For this study, we expanded on these findings by monitoring the distribution of a three-drug chemotherapeutic cocktail. First, we imaged both irinotecan and folinic acid, which are readily observed using positive ion MALDI-MSI. After 24 hours of dosing, folinic acid and irinotecan both concentrate to the core of the spheroids (Figure 3a), which contains mostly dead and dying cells. Folinic acid was identified by its sodium adduct (m/z 496.4) and its identity was confirmed with MALDI-MS/MS analysis (S-Figure 3). Folinic acid augments the therapeutic effects of 5-FU in cancer patients by increasing the half-life of 5-FU in the body.38,39 5-FU is metabolized to 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (FdUMP) which binds to and inhibits thymidylate synthase (TS) in a complex with a folinic acid metabolite.49 Folinic acid is metabolized to 5–10 methylenetetrahydrofolate (5,10-CH2-THF), which forms an inhibitory complex with 5-FdUMP and TS. This complex diminishes thymidylate synthesis and impairs DNA synthesis.49 5,10-CH2-THF is further metabolized to 5,10-CH=THF by methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase and NADP+.50 The 5,10-CH=THF metabolite (m/z 456.4) was detected in the middle quiescent and outer proliferative region of the spheroids (Figure 3b). The spatial localization of the folinic acid parent drug contrasted with the localization of the folinic acid metabolite. Since the core region of the spheroid contains mostly dead and dying cells, less drug metabolism is expected in this region, resulting in an accumulation of folinic acid in the core. The outer region of the spheroid, which contains actively proliferating cells, is capable of metabolizing folinic acid. This localization, with parent drugs localizing to the core and metabolites to the periphery of spheroids corresponds with our previous findings for irinotecan.24,25

Figure 3.

MALDI-MSI of treated spheroids. (a) Irinotecan and folinic acid both localized to the core of spheroids following 24 hours of dosing. (b) A folinic acid metabolite was detected in the outer periphery of the spheroids, a spatial region populated by actively proliferating cells.

Quantitation of 5-Fluorouracil in Spheroids

Molecular imaging of the distribution of 5-FU has been previously shown with the use of an 18F analog of 5-FU and positron emission tomography (PET).51 5-FU is a low molecular weight (130 g/mol) molecule that is not easily detectable in positive and negative ion mode, making it a challenging target for MALDI-MSI experiments. To determine if 5-fluorouracil penetrated spheroids, we performed a small molecule extraction on treated spheroids and quantified 5-fluoruracil within spheroids using LC-MS. A standard curve was generating using internal standard calibration and all samples were run in triplicate. Following 24 hours of dosing we determined the final concentration of 5-fluoruracil to be 15.9 μg/ml. This concentration is within the clinically accepted range of the 5-FU and below the concentration maximum of 18.2 μg/ml.52

iTRAQ Proteomic Analysis

To determine global proteomic changes induced by the FOLFIRI combina-tion chemotherapy, we used iTRAQ based quantitative proteomics (Figure 2). In iTRAQ proteomics, reporter ion intensities for each peptide can be determined via tandem mass spectrometry. This method allows for protein identification along with fold-change quantification information between treated and untreated samples. Proteins were harvested from treated and untreated spheroids in biological duplicate. We performed two separate iTRAQ experiments comparing treated spheroids to their untreated counterparts. Proteins were digested with trypsin overnight and peptides were labeled with iTRAQ tags. The combined sample mixture was first fractionated with SCX then further fractioned with reversed-phase ultraperformance liquid chromatography and analyzed with a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer.

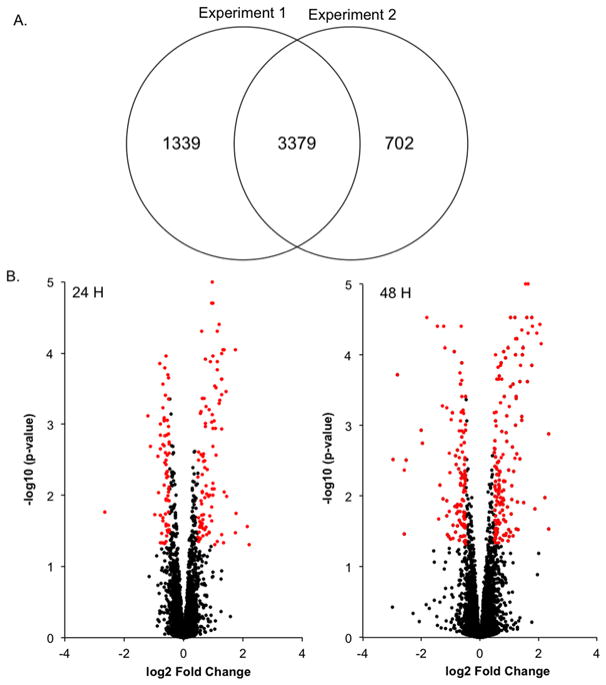

Overall 5,420 unique proteins were identified and quantified across the two iTRAQ experiments at a 1% false discovery rate (Figure 4a). MaxQuant output files were then uploaded to Proteosign for statistical analysis. Proteosign calculated average log2 fold changes of treated vs control samples as well as p-values for each of the identified proteins by adapting statistical methods that are well-established in the microarray field.48,53 The identified proteins were then plotted on a volcano plot according to their average log2 fold change and p-value for 24 and 48 hours of treatment (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Quantitative proteomics. (a) Overlap between two iTRAQ experiments. (b) Volcano plots following 24 and 48 hours of treatment. Significantly regulated proteins are shown in red.

To determined cutoffs for differentially regulated proteins, the log2 fold-changes of control replicates were compared and plotted as a histogram to determine biological and experimental variation. The fold changes were distributed around zero with a standard deviation of 0.24 (S-Figure 1). The threshold for differentially expressed proteins was set at two standard deviations from the mean (log2 fold-change ≤ −0.48 or ≥ 0.48). We also utilized calculated p-values for each protein as determined by Proteosign and chose a p-value < 0.05 as the cut off for differentially regulated proteins. Using these two filters, we found 171 unique proteins to be differentially regulated following 24 hours of dosing, and 269 unique proteins to be differentially regulated after 48 hours of dosing. Regulated proteins are shown in red in Figure 4B. There was also a high degree of correlation between regulated proteins identified in both 24 and 48 hour experiments (Figure 5). Several histone proteins that play important roles in nucleosomes were found to be upregulated following treatment. Most of the histone proteins that were upregulated at 24 hours of treatment showed increased up regulation following 48 hours of doing.

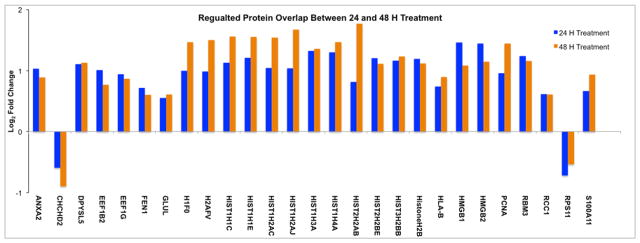

Figure 5.

Protein overlap between 24 and 48 hours of dosing. Proteins identified in both experiments showed directional correlation.

The identified differentially regulated proteins and their log2 fold changes were uploaded to Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). IPA performed functional classification to further characterize the differentially regulated proteins and identified enriched functional themes and pathways identified by our quantitative proteomic data (S-Figure 4). IPA analysis revealed the enrichment of several canonical pathways for both 24 and 48 hour treatments (S-Table 1). The most highly-enriched pathways included eIF2 signaling, mTOR signaling, and VEGF signaling.

Following both 24 and 48 hours of dosing, Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2 (eIF2) signaling was found to be the most enriched pathways. The eIF2 pathway was downregulated with a Z-score of −4.58. Our proteomic analysis mapped 39 pro-teins in the eIF2 pathway. The initiation phase of protein synthesis requires nu-merous factors including eIF2 signaling proteins. eIF2 proteins are essential in the initiation of mRNA translation and we attribute downregulation of this pathway to the FOLFIRI treatment. Within the eIF2 pathway we found several ribosomal proteins (RPs) to be downregulated. RPs have clinical significance to many hu-man cancers and play roles in ribosomal construction for protein synthesis as well as extra ribosomal roles.54 Studies have previously shown that downregulation of ribosomal proteins can be induced by chemotherapies such as 5-FU.55

IPA analysis also revealed the enrichment of the mTOR and VEGF signaling pathways following 24 hours of treatment and the down-regulation of the path-ways following 48 hours of treatment. The mTOR pathway is activated in the majority of human cancers and leads to an increase VEGF secretion.56 These signaling pathways play a role in the promotion of angiogenesis, and the down-regulation of these pathways is a positive effect of the administered combination chemotherapy, indicating clinical efficacy.

Molecular and cellular functions affected by treatment were also assessed with IPA analysis at both 24 hours (S-Table 2) and 48 hours (S-Table 3) of treatment. The analysis showed an enrichment of several molecular and cellular functions including: lipid metabolism, molecular transport, protein synthesis, small molecule biochemistry, cellular compromise, proliferation, death and survival. Lipid metabolism participates in many cellular processes including cell survival, apoptosis, chemotherapy response and drug resistance.57 Alterations in lipid metabolism are common in many cancers and drug candidates targeting lipogenic enzymes are being investigated as possible drug targets.58

Regulator of Chromosome Condensation (RCC1) was found to be upregulated following treatment. RCC1 is a protein that has previously been shown to be a regulator of the cell cycle by detecting unreplicated DNA and transducing an in-hibitory signal to prevent the activation of mitosis.61 A recent in vitro study, examining doxorubicin treated cells, showed that RCC1 functions as the DNA damage resistance-promoting factor in HCT 116 cells.62 The study also indicates that HCT 116 cells undergoing DNA damage from chemotherapy select for cells with high RCC1 expression and correlates with our findings.

Conclusions

In this study, an in vitro platform was used to investigate the effects of combination chemotherapy on colon cancer spheroids. A 3D printed fluidic device was used to administer chemotherapeutics to tumor mimics. The clinically relevant FOLFIRI combination chemotherapy was used in accordance with a clinical dosing schedule. Following treatment, spheroids were analyzed for drug penetration and metabolism and quantitative proteomic changes.

MALDI-MSI data revealed complete penetration of irinotecan and folinic acid to the core of the tumor spheroids following 24 hours of dosing. Imaging data also showed the presence of a folinic acid metabolite to the outer prolifera-tive region of the spheroid. The contrasting localization of folinic acid and its me-tabolites corresponded to previous results for irinotecan. The inner core of the tumor spheroid contains mostly dead and dying cells and therefore is unable of metabolizing the administered chemotherapeutics. In contrast, the outer region of the spheroids contains actively proliferating cells and can metabolize adminis-tered drugs. MALDI-MSI analysis of 5-fluorouracil presented many challenges stemming from 5-FU’s low molecular weight. 5-FU quantification using nLC-MS/MS revealed the drug concentration was within the clinical range for 5-FU dosing. Altogether, this data demonstrates that established chemotherapeutics are able to penetrate and be metabolized in the spheroid model system.

ITRAQ was used for the investigation of proteomic changes induced by the FOLFIRI combination chemotherapy. Over 5,400 proteins were identified and quantified. Treatment induced the regulation of several proteins involved in cancer-associated pathways. The eIF2 signaling pathway was the most enriched canonical pathway and is associated with cellular response to stress related stimuli. Within the eIF2 pathway we saw the downregulation of several ribosomal proteins. We also found the upregulation of RCC1 following both 24 and 48 hours of treatment. This protein has previously been shown to be a damage re-sistance-promoting factor in HCT 116 cells. Overall, this study illustrates that the analysis of combination chemotherapeutics can be performed using a 3D-printed dosing device with three-dimensional cell cultures. This platform provides a high-throughput system to test new potential chemotherapeutics in colon, and other, cancers and screen for drugs with the greatest efficacy prior to animal models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

GJL and ABH were supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM110406). ABH was also supported by National Science Foundation (CAREER Award, CHE-1351595). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the Notre Dame Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Facility (MSPF) and the Dana M. Spence laboratory. The UltrafleXtreme instrument (MALDI-TOF-TOF) was acquired through National Science Foundation award #1625944.

Footnotes

Additional information as noted in text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Tumour Microenviroment. 2006;6:583–592. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginai M, Elsby R, Hewitt CJ, Surry D, Fenner K, Coopman K. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(19–20):922–935. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lengyel E, Burdette JE, Kenny HA, Matei D, Pilrose J, Haluska P, Nephew KP, Hales DB, Stack MS. Oncogene. 2013;33(28):3619–3633. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinci M, Gowan S, Boxall F, Patterson L, Zimmermann M, Court W, Lomas C, Mendiola M, Hardisson D, Eccles SA. BMC Biol. 2012;29:1–20. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada KM, Cukierman E. Cell. 2007;130(4):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debnath J, Brugge JS. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(9):675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrc1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maltman DJ, Przyborski Sa. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(4):1072–1075. doi: 10.1042/BST0381072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin R, Chang H. Biotechnol J. 2008;3:1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/biot.200700228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chitcholtan K, Asselin E, Parent S, Sykes PH, Evans JJ. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Töyli M, Rosberg-Kulha L, Capra J, Vuoristo J, Eskelinen S. Lab Investig. 2010;90(6):915–928. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freyer JP, Sutherland RM. Cancer Res. 1980;40:3956–3965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutherland RM. Science (80-) 1988;240:177–240. doi: 10.1126/science.2451290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culo F, Yuhas JM, Ladman AJ. Br J Cancer. 1980;41:100–112. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1980.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keithley RB, Weaver EM, Rosado AM, Metzinger MP, Hummon AB, Dovichi NJ. Anal Chem. 2013;85:8910–8918. doi: 10.1021/ac402262e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMahon KM, Volpato M, Chi HY, Musiwaro P, Poterlowicz K, Patterson LH, Phillips RM, Sutton CW. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2863–2875. doi: 10.1021/pr2012472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altmann B, Welle A, Giselbrecht S, Truckenmüller R, Gottwald E, Altmann B, Welle A, Giselbrecht S. World J Stem Cells. 2009;1(1):43–48. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v1.i1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Milotti E, Chignola R. PLoS One. 2010;5(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedrich J, Ebner R, Kunz-Schughart La. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83(11–12):849–871. doi: 10.1080/09553000701727531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu X, Hummon AB. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;577–586 doi: 10.1007/s13361-014-1071-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmins NE, Dietmair S, Nielsen LK. Angiogenesis. 2004;7:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s10456-004-8911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong S, Lee J, Shin Y, Chung S, Kuh H. PLoS One. 2016;1–17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sobrino A, Phan DTT, Datta R, Wang X, Hachey SJ, Romero-López M, Gratton E, Lee AP, George SC, Hughes CCW. Sci Rep. 2016 Aug;6:31589. doi: 10.1038/srep31589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottfried E, Kunz-schughart LA, Andreesen R, Kreutz M. Cell Cycle. 2006;691–695 doi: 10.4161/cc.5.7.2624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaBonia GJ, Lockwood SY, Heller AA, Spence DM, Hummon AB. Proteomics. 2016;16:1814–1821. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu X, Weaver EM, Hummon AB. Anal Chem. 2013;85(13):6295–6302. doi: 10.1021/ac400519c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu X, Hummon AB. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov;6:38507. doi: 10.1038/srep38507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weaver EM, Hummon AB, Keithley RB. Anal Methods. 2015;7:7208–7219. doi: 10.1039/C5AY00293A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solon EG, Schweitzer A, Stoeckli M, Prideaux B. AAPS J. 2010;12(1) doi: 10.1208/s12248-009-9158-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panthani MG, Khan TA, Reid DK, Hellebusch DJ, Rasch MR, Maynard JA, Korgel BA. Nano Lett. 2013;13:4294–4298. doi: 10.1021/nl402054w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruin D, Kuhnast B, Chassoux F, Daumas-duport C, Ezan E, Tavitian B. J Pharmacol. 2006;316(1):79–86. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.089102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Estelrich J, Sanchez-Martin MJ, Busquets MA. Int J Nanomedicine. 2015:1727–1741. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S76501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rao W, Pan N, Yang Z. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2015;26:986–993. doi: 10.1007/s13361-015-1091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu X, Hummon AB. Anal Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00419. 150618082425003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seeley EH, Caprioli RM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(47):18126–18131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801374105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacAleese L, Stauber J, Heeren RMa. Proteomics. 2009;9(4):819–834. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wheatcraft DRA, Liu X, Hummon AB. J Vis Exp. 2014;94 doi: 10.3791/52313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gustavsson B, Carlsson G, Machover D, Petrelli N, Roth A, Schmoll H, Tveit K, Gibson F. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2015;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Erlichman C, Carlson RW, Valone F, Labianca R, Park R, Hospital M, Hospital CB, Buyse M. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(6):896–903. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thirion P, Michiels S, Pignon JP. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18) doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lockwood SY, Meisel JE, Monsma FJ, Spence DM. Anal Chem. 2016;88(3):1864–1870. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson KB, Lockwood SY, Martin RS, Spence DM. Anal Chem. 2013;85(12):5622–5626. doi: 10.1021/ac4009594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bauer KM, Lambert PA, Hummon AB. Proteomics. 2012:1928–1937. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H, Hummon AB. Anal Chem. 2011;83(22):8794–8801. doi: 10.1021/ac202356g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feist PE, Sun L, Liu X, Dovichi NJ, Hummon AB. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2015:654–658. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durand RE. Radiat Res. 1980;81:85–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cartwright TH. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2012;11(3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falcone A, Pisa U, Brunetti IM. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(13):1670–1676. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Efstathiou G, Antonakis AN, Pavlopoulos GA, Theodosiou T, Divanach P, Trudgian DC, Thomas B, Papanikolaou N, Aivaliotis M, Acuto O, Iliopoulos I. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W300–W306. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taflin H, Wettergren Y, Odin E, Carlsson G, Derwinger K. Clin Med Insights. 2014:15–20. doi: 10.4137/CMO.S12701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dimri Goberdhan P, Ames Ferro-Luzzi, D’Ari Linda, Giovanna Rabinowitz JC. J Bacteriol. 1991;173(17):175251. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5251.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hino-shishikura A, Suzuki A, Minamimoto R, Shizukuishi K, Ct PET. Appl Radiat Isot. 2013;75:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bocci G, Danesi R, Paolo A, Di Innocenti F, Allegrini G, Falcone A, Melosi A, Battistoni M, Barsanti G, Conte PF, Del Tacca M. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3032–3037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smyth GK. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3(1):1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Huang CJ, Yang SH, Lee CL, Cheng YC, Tai SY, Chien CC. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):6–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burger K, Muhl B, Harasim T, Rohrmoser M, Malamoussi A, Orban M, Kellner M, Gruber-Eber A, Kremmer E, Hölzel M, Eick D. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(16):12416–12425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karar J, Maity A. Front Mol Neurosci. 2011;4 doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2011.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huang C, Freter C. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:924–949. doi: 10.3390/ijms16010924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beloribi-djefa S, Vasseur S, Guillaumond F. Oncogenesis. 2016;5:1–10. doi: 10.1038/oncsis.2015.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bell DA, Morrison B. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;60(1):13–26. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(91)90108-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holdenrieder S, Stieber P. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2009;46(1):1–24. doi: 10.1080/10408360802485875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dasso M. Trends Biochem Sci. 1993;18(3):96–101. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(93)90161-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cekan P, Hasegawa K, Pan Y, Tubman E, Odde D, Chen JQ, Herrmann MA, Kumar S, Kalab P. Mol Biol Cell. 2016;27(8):1346–1357. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E16-01-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.