Abstract

Objective

In US EDs, low back pain patients are often treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and muscle relaxants. We compared functional outcomes among patients randomized to a one week course of naproxen + placebo versus naproxen + orphenadrine or naproxen +methocarbamol.

Methods

This was a randomized, double-blind, comparative effectiveness trial conducted in two urban EDs. Patients presenting with acute, non-traumatic, non-radicular low back pain were enrolled. The primary outcome was improvement on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) between ED discharge and one week later. All patients were given 14 tablets of naproxen 500mg, to be taken twice a day, as needed for low back pain. Additionally, patients were randomized to receive a one week supply of orphenadrine 100mg, to be taken twice a day as needed, methocarbamol 750mg, to be taken as one or two tablets, three times per day as needed or placebo. All patients received a standardized 10 minute low back pain educational session prior to discharge.

Results

240 patients were randomized. Baseline demographic characteristics were comparable. The mean RMDQ of patients randomized to naproxen + placebo improved by 10.9(95%CI: 8.9,12.9) RMDQ points. The mean RMDQ of patients randomized to naproxen + orphenadrine improved by 9.4(95%CI: 7.4,11.5). The mean RMDQ of patients randomized to naproxen + methocarbamol improved by 8.1(95%CI: 6.1,10.1). None of the between group differences surpassed our threshold for clinical significance. Adverse events were reported by 17%(95%CI:10, 28%) of placebo patients, 9%(95%CI:4, 19%) of orphenadrine patients, and 19%(95%CI:11, 29%) of methocarbamol patients.

Conclusion

Among ED patients with acute, non-traumatic, non-radicular low back pain, combining naproxen with either orphenadrine or methocarbamol did not improve functional outcomes when compared to naproxen +placebo.

Introduction

Background

Low back pain causes 2.4% of visits to US emergency departments (ED) resulting in 2.6 million visits annually. (1) In general, outcomes for these patients are unfavorable. One week after ED discharge, 70% of patients report persistent back-pain related functional impairment and 69% report analgesic use within the previous 24 hours.(2) Among the subset of ED patients who present with acute, new-onset low back pain, outcomes are generally better--most will recover, although 10–20% of this group reports moderate or severe low back pain three months later and 30% will report persistent low back pain-related functional impairment.(3, 4)

Importance

It is not clear which medications should be prescribed for acute low back pain. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are more efficacious than placebo with regard to low back pain relief, global improvement, and requirement of analgesic medication (5) but are insufficient treatment for as many as half of all ED low back pain patients, who continue to suffer during the days after ED discharge despite use of NSAIDs. Treatment of low back pain with multiple concurrent medications is common in the ED--emergency physicians often prescribe skeletal muscle relaxants or opioids in combination with NSAIDs.(6) However, combining oxycodone/acetaminophen, diazepam, or cyclobenzaprine (a skeletal muscle relaxant), with an NSAID does not improve outcomes.(3) It remains uncertain if adding other skeletal muscle relaxants to NSAIDs improves low back pain outcomes.

Two specific skeletal muscle relaxants, orphenadrine and methocarbamol, are each used in more than 250,000 U.S. ED visits for low back pain annually, although scant evidence exists to determine the appropriateness of this approach.(7) Orphenadrine is a centrally acting medication with prominent anti-cholinergic and antihistaminic properties. The mechanism of action is not understood. Efficacy in low back pain may be related to non-specific analgesic properties. The mechanism of action of methocarbamol has also not been established. Its efficacy is thought to be related to CNS effects rather than direct effects on skeletal muscles.

Goals of this investigation

Given the poor pain and functional outcomes that persist beyond an ED visit for acute low back pain, we conducted a clinical trial to determine whether combining either orphenadrine or methocarbamol with an NSAID is more effective than NSAID monotherapy for the treatment of acute, non-traumatic, non-radicular low back pain. We specifically evaluated the following two hypotheses: 1) The combination of naproxen + orphenadrine provides greater relief of low back pain than naproxen + placebo one week and three months after an ED visit, as measured by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ); 2) The combination of naproxen + methocarbamol provides greater relief of low back pain than naproxen + placebo one week and three months after an ED visit, as measured by the RMDQ.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a randomized, double-blind, comparative effectiveness study, in which we enrolled ED patients with musculoskeletal low back pain at the time of discharge and followed them by telephone seven days and three months later. Every patient received standard-of-care therapy, consisting of naproxen and a brief low back pain educational session. Patients were then randomized to orphenadrine, methocarbamol, or placebo. The Albert Einstein College of Medicine Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study. Written consent to participate was obtained for all study participants. The study was registered online at http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02665286). Enrollment commenced in March 2016 and continued for 11 months. We report this trial in accordance with CONSORT standards.

This study was performed in the two academic EDs of Montefiore Medical Center (the Bronx, NY) with a combined annual census of 180,000 adult visits. Salaried, full-time, bilingual (English and Spanish) technician-level research associates, staffed the EDs 18–24 hours per day, seven days per week during the study period.

Selection of participants

Our goal was to include a broad representation of patients with musculoskeletal back pain who would potentially respond to the investigational medications. The presence or absence of palpable spasm of the paraspinal muscles was not used as an entry criterion because the clinical significance and reliability of this finding is uncertain.(8) Patients were included if they were at least 18 and no more than 69 years old, and presented to one of the participating EDs primarily for management of low back pain, defined as pain originating between the lower border of the scapulae and the upper gluteal folds. At the conclusion of the ED visit, the patient was required to have a diagnosis consistent with non-traumatic, non-radicular, musculoskeletal low back pain and was to be discharged home. To participate, patients were required to have a baseline score of > 5 on the Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (Appendix 1). Patients were excluded from participation if they reported radicular pain below the gluteal folds, pain duration >2 weeks, a baseline back pain frequency of at least once per month or substantial, direct trauma to the back within the previous month. Patients were also excluded from participation if they would not be available for follow-up, for pregnancy or breast feeding, for a chronic pain syndrome defined as use of any analgesic medication on a daily or near-daily basis, or for allergy, intolerance, or contra-indication to the investigational medications.

Interventions

Study participants were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to orphenadrine, methocarbamol, or placebo. Participants in the orphenadrine arm were instructed to take naproxen 500mg tablets twice per day + orphenadrine 100mg twice per day. Participants in the methocarbamol arm were instructed to take naproxen 500mg tablets twice per day + methocarbamol 750mg as 1 or 2 tabs, three times per day—thus, they could take as much as 1500mg of methocarbamol three times per day. Patients randomized to placebo were randomly assigned to two different sets of dosing instructions to match the different dosing regimens of the active arms--half of the participants were instructed to take the investigational capsule twice per day while the other half were instructed to take it as one or two capsules three times per day.

We incorporated a flexible dosing plan in the methocarbamol arm in an effort to maximize effectiveness while minimizing side effects. In this study arm, patients were instructed to take one or two pills of the methocarbamol every 8 hours. If one tablet of the methocarbamol afforded sufficient relief, there was no need for the patient to take the second tablet. However, if the patient had not experienced sufficient relief within 30 minutes of taking one investigational medication tablet, they were instructed to take the second tablet. We chose this method of administration because optimal dosing of methocarbamol has not been established. We believe the dosing regimen we chose was sufficient to determine effectiveness while not exposing patients to unnecessary risk.(9–11) Orphenadrine is only manufactured in 100mg extended release tablets and therefore was not amenable to flexible dosing. All study patients were given 14 naproxen tablets, a seven day supply, and a sufficient number of investigational tablets to last 7 days.

The research pharmacist performed randomization in blocks of six based on a sequence generated at http://randomization.com. Each block of six contained two orphenadrine assignments, two methocarbamol assignments, one placebo assignment dosed as one capsule twice daily (to mirror orphenadrine dosing), and one placebo assignment dosed as 1–2 capsules three times daily (to mirror methocarbamol dosing). Therefore, although patients did not know whether they had been assigned to active medication or placebo, they may have deduced to which medication they were not assigned. This did not threaten the internal validity of the study because patients did not know if they received active medication or placebo.

Naproxen was not masked. Orphenadrine, methocarbamol, and placebo were masked by placing tablets into identical capsules, which were packed with scant amounts of lactose and sealed. This masking occurred in a secure location inaccessible to ED personnel. Study participants were presented with two bottles of medication. The first bottle, containing the naproxen, was labeled in a typical manner. The second bottle, containing orphenadrine, methocarbamol, or placebo, was labeled as investigational medication. Patients were instructed to use the second bottle of investigational medication only as needed for moderate or severe low back pain.

Research personnel provided each patient with a 10-minute educational intervention. This was based on the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Disease’s Handout on Health: Back Pain information webpage (available at http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Back_Pain/default.asp) Research personnel reviewed each section of the information sheet with the patient and elicited questions.

Measurements

The Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ, Appendix). The RMDQ is a 24-item low back pain functional scale recommended for use in low back pain research.(12) Its yes/no format is amenable to telephone follow-up. Higher scores signify greater low back-related functional impairment. The baseline questions referred to the time period immediately prior to ED presentation (“Before you came to the ER today, were you able to…..”), while the one week and three month follow-up questions referred to the 24 hours preceding the follow-up telephone calls.

Ordinal pain scale. Study participants described their back pain using the descriptors severe, moderate, mild, or none. Though not validated, this measure has been used frequently in ED-based low back pain studies.(2–4, 13)

Medication requirements. Study participants were asked to answer the question, “Did you require any medication to treat your low back pain?”

Low back pain frequency. Study participants were asked to describe the frequency of their low back pain using the descriptors always, usually, sometimes, rarely, or not at all. Low back pain symptomatology is quite variable. Some patients experience no pain unless they move a certain way. Others experience a constant low level of pain. This question helps determine the symptomatic burden of the low back pain in the patient’s daily life.

Satisfaction, as measured by response to this question: The next time you go to the ER with low back pain, do you want to receive the same combination of medications? This question, often used in ED-based acute pain research, allows patients to weigh for themselves the relative efficacy versus tolerability of the investigational medications.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was improvement in the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) between ED discharge and 1 week follow-up.

The following secondary outcomes were assessed one week after ED discharge: a) Severity of low back pain during the previous 24 hours; b) the frequency of low back pain during the previous 24 hours; c) requirement of medication for low back pain during the previous 24 hours; d) satisfaction with treatment; e) numbers of days until able to return to usual activities; f) frequency of follow-up visits to healthcare providers; and g) frequency of new symptoms attributable to the investigational medications. Adverse medication effects were elicited using an open-ended question. All study participants were also asked about three specific adverse medication effects: drowsiness, dizziness, and stomach irritation. Study participants were asked to rate the severity of these latter three symptoms as none, a little, or a lot.

The following secondary outcomes were assessed three months after ED discharge: a) score on the RMDQ; and b) severity of low back pain during the previous week using the four item ordinal scale described above.

The research associates, who were blinded to assignment, collected all of the data using structured interviews.

Analysis

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed in which all randomized patients with available follow-up data were included in the analysis regardless of whether or not they actually used the investigational medication. The primary outcome was a comparison of the change in RMDQ between baseline and one week. Results are reported as means with 95% CI. Between group differences are reported with 95% CI. Dichotomous outcomes are reported as n/N (%). Between group differences (absolute risk reduction) are reported with 95%CI. Continuous outcomes are reported as means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with interquartile range (IQR). We performed a sub-group analysis of the primary outcomes among those patients who used the investigational medication at least twice. SPSS v.21 (SPSS: An IBM company) was used for all analyses.

We based our sample size calculation assumptions on a recently completed low back pain clinical trial(3) and a widely accepted minimum clinically important improvement of 5 points on the RMDQ.(14) Using a standard alpha of 0.05 and a beta of 0.20, we determined the need for 50 subjects in each arm. To account for protocol violations, patients lost-to-follow-up, and to ensure sufficient power for the intention to treat analysis (in previous work, up to 1/3 of enrolled patients did not use the investigational medication), we enrolled 80 patients in each arm.

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

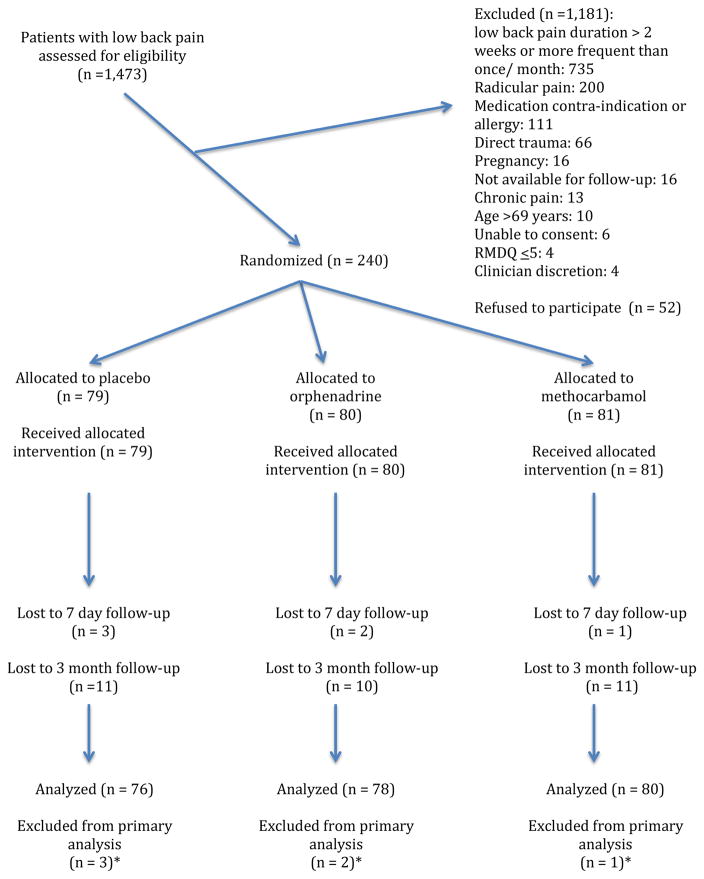

During the accrual period, 1473 patients with low back pain were approached for participation and 240 eligible patients were randomized (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics were comparable between the groups. (Table 1)

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Naproxen + placebo (n=79 ) | Naproxen + orphenadrine (n=80) | Naproxen + methocarbamol (n= 81) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years (SD) | 39 (12) | 40 (12) | 38 (12) |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 45 (57%) | 46 (58%) | 40 (49%) |

| Women | 34 (43%) | 34 (43%) | 41 (51%) |

| Work status | |||

| Unemployed | 8 (10%) | 8 (10%) | 7 (9%) |

| Student | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| <30 hours/week | 10 (13%) | 12 (15%) | 13 (16%) |

| ≥30 hours/week | 61 (77%) | 60 (75%) | 61 (75%) |

| Median RMDQ at time of ED visit (IQR) | 19 (16, 22) | 19 (15, 21) | 19 (16, 21) |

| Median duration of low back pain prior to presentation to ED in hours (IQR) | 48 (24, 108) | 72 (24, 96) | 48 (24, 120) |

| Previous episodes of low back pain | |||

| Never before | 21 (27%) | 28 (35%) | 25 (31%) |

| Few times before | 44 (56%) | 44 (55%) | 47 (58%) |

| At least once/year | 14 (18%) | 8 (10%) | 9 (11%) |

| Depression screen positive1 | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise stated.

RMDQ: Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. This is a 24 item instrument measuring low back pain related functional impairment. On this instrument, 0 represents no low back pain related functional impairment and 24 represents maximum functional impairment.

Patients were asked two screening questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire: a) Before your back pain began, how often were you bothered by little pleasure or interest in doing things? b) Before your back pain began, how often were you bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless? Patients who responded to either question “More than half the days” or “Nearly every day” were considered to screen positive for depression.

Main results

One week after the ED visit, patients randomized to placebo improved by a mean of 10.9 (95%CI: 8.9, 12.9) RMDQ points while orphenadrine patients improved by 9.4 (95%CI: 7.4, 11.5) and methocarbamol patients improved by 8.1 (95%CI: 6.1, 10.1). The difference between orphenadrine and placebo was 1.5 RMDQ points (95%CI: −1.4, 4.3) while the difference placebo and methocarbamol was 2.8 (95%CI: 0, 5.7). Secondary outcomes were similar among the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

One-week outcomes among study participants who completed one-week follow-up

| Outcome variable | Naproxen + placebo (n=79) | Naproxen + orphenadrine (n=80) | Naproxen + methocarbamol (n=81) | Difference between orphenadrine vs. placebo (95%CI) | Difference between methocarbamol vs. placebo (95%CI) | Difference between orphenadrine vs. methocarbamol (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worst low back pain during previous 24 hours | 1% (−14, 16%) | 5% (−11, 20%) | 5% (−10, 20%) | |||

| Mild/none | 50 (66%) | 52 (67%) | 49 (61%) | |||

| Moderate/Severe | 26 (34%) | 26 (33%) | 31 (39%) | |||

| missing | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Frequency of low back pain during previous 24 hours | 4% (−12, 20%)* | 7% (−8, 23%)* | 11% (−4, 27%)* | |||

| Never/rarely | 36 (47%) | 40 (51%) | 32 (40%) | |||

| Sometimes | 26 (34%) | 22 (28%) | 23 (29%) | |||

| Frequently/always | 14 (18%) | 16 (21%) | 25 (31%) | |||

| missing | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Use of medication for low back pain during the 24 hours prior to one week follow-up | 4% (−12, 20%) | 7% (−8, 23%) | 11% (−4, 27) | |||

| No meds | 34 (45%) | 38 (49%) | 30 (38%) | |||

| Took meds | 42 (55%) | 40 (51%) | 50 (63%) | |||

| missing | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Same medications during subsequent episode of low back pain1 | 0% (−15, 15%)** | 3% (−12, 18%)** | 3% (−12, 17%)** | |||

| Yes | 51 (68%) | 53 (68%) | 51 (65%) | |||

| No | 17 (23%) | 20 (26%) | 16 (21%) | |||

| Not sure | 7 (9%) | 5 (6%) | 11 (14%) | |||

| missing | 4 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Median days until usual activities (IQR)2 | 4 (2, 7) | 3 (2, >7) | 4 (2, >8) | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.0) | 0.3 (−0.6, 1.1) | 0.1 (−0.8, 1.0) |

| missing | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Participants were asked: “The next time you have back pain, do you want to take the same medications you’ve been taking this past week?”

Patients who had not yet recovered at the time of the one week phone call were categorized as >7 days.

Never/rarely versus sometimes/frequently/always

Yes versus no/not sure

A large majority of patients used naproxen at least once per day (Table 3). Use of the investigational medication was slightly less robust. We examined outcomes among participants who used the investigational medication “sometimes,” “daily,” or “several times daily”. In this subgroup analysis, placebo patients reported one week RMDQ improvement of 11.3 (95%CI: 9.2, 13.5) points, orphenadrine 9.1 (95%CI: 6.8, 11.4) points and methocarbamol 8.2 (95%CI: 5.9, 10.6) points.

Table 3.

Use of investigational medication and healthcare resources within one week of ED discharge

| Outcome | Naproxen + placebo, n (%) | Naproxen + orphenadrine, n (%) | Naproxen + methocarbamol, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of naproxen use | |||

| More than once/day | 50 (67%) | 48 (62%) | 41 (53%) |

| Once/day | 19 (25%) | 19 (24%) | 19 (24%) |

| Sometimes | 5 (7%) | 5 (6%) | 10 (13%) |

| Only once | 1 (1%) | 4 (5%) | 5 (6%) |

| Never | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) |

| missing | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Frequency of placebo/orphenadrine/methocarbamol use | |||

| More than once/day | 38 (51%) | 36 (46%) | 34 (44%) |

| Once/day | 22 (29%) | 21 (27%) | 23 (29%) |

| Sometimes | 9 (12%) | 9 (12%) | 7 (9%) |

| Only once | 4 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 6 (8%) |

| Never | 2 (3%) | 8 (10%) | 8 (10%) |

| missing | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Healthcare resources utilized | |||

| No visit to any clinician | 67 (88%) | 66 (85%) | 65 (81%) |

| Subsequent ED visit | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 5 (6%) |

| Primary care | 5 (7%) | 4 (5%) | 7 (9%) |

| MD specialist1 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) |

| Complementary therapy2 | 2 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 6 (8%) |

| missing | 3 | 2 | 1 |

Orthopedist, pain management

Chiropractic, massage, physical therapy

More than 80% of study participants did not visit another healthcare provider within one week of ED discharge (Table 3). Among those who did visit a healthcare provider, participants reported follow-up visits to primary care, repeat ED visit, and complementary/alternative practitioners.

Adverse events were relatively uncommon and comparable among the groups (Appendix 2). Other than the symptoms reported in Table 4, only nausea was reported by more than two participants. Nausea was reported by three methocarbamol patients and one placebo patient. There were no serious or unexpected adverse events.

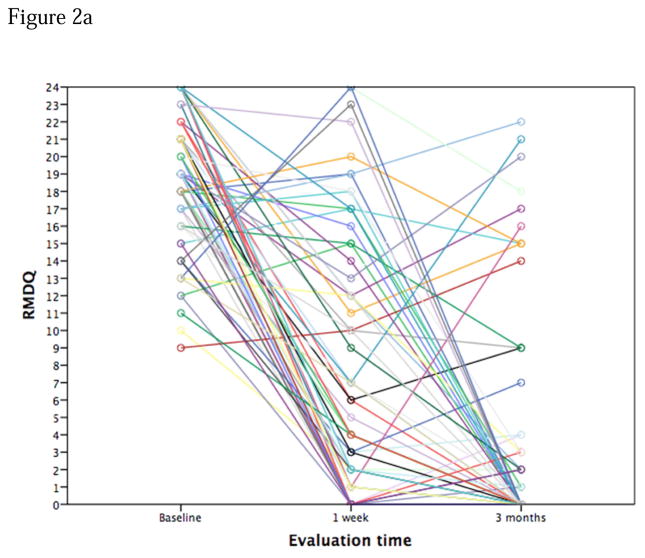

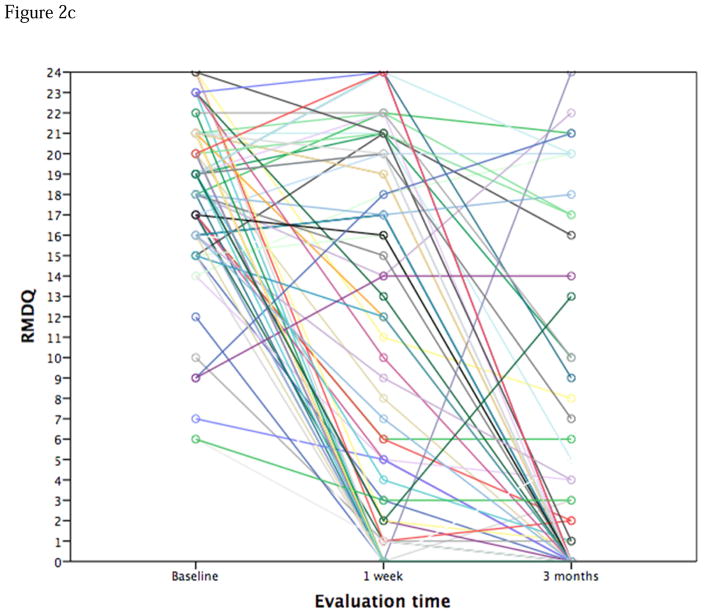

By three months after the ED visit, most patients had recovered completely, although one quarter of the sample reported RMDQ scores ≥ 8, indicating substantial functional impairment (Appendix 5&6). There were no differences in three month pain or functional outcomes among the groups.

Limitations

Our work has a number of limitations. First, this was a study of effectiveness rather than efficacy, meaning that we tested the utility of the investigational medications in a real world scenario. It is possible that orphenadrine and methocarbamol may have alleviated back pain if study participants were mandated to take these medications on a regular schedule for several days. Second, studies of this type are susceptible to selection bias. Some of the bias we know about—because patients with chronic low back pain were excluded, the results of this study are not applicable to patients with chronic low back pain. However, we do not know whether potentially eligible patients who were screened were different than potentially eligible patients who were missed. Similarly, we do not know if the 52 patients who refused to participate were different than those who were enrolled. Third, the measurement instruments we used for secondary outcome assessment have not been validated. Therefore, we do not know whether they truly captured the patient’s experience. Finally, we conducted this study in one urban healthcare system serving a socio-economically depressed population. Because back pain outcomes may be associated with socio-economic variables, our results can be generalized most appropriately to EDs that serve similar disadvantaged patient populations.

Discussion

In this randomized, double blind comparative effectiveness study, adding skeletal muscle relaxants to naproxen did not improve functional and pain outcomes among patients with acute, non-traumatic, non-radicular low back pain. Many of these patients with acute low back pain had improved by the one week follow-up, though more than one-third reported persistent moderate or severe low back pain. At three months, 45% of our cohort reported low back related functional impairment.

Orphenadrine and methocarbamol are each used in more than 250,000 US ED visits for low back pain annually. Among patients with acute low back pain or muscle spasm, monotherapy with methocarbamol has been shown to be superior to placebo with regard to both pain and functionality (Appendix 7).(11, 15) We are not aware of other randomized studies in which methocarbamol has been combined with an NSAID. Orphenadrine has demonstrated superiority to placebo among patients with acute low back pain, though was not superior to monotherapy with aspirin (Appendix 8).(16–19) We are not aware of other low back pain studies in which orphenadrine was combined with an NSAID.

Overall, one week and three month outcomes in this study revealed that most patients experience normalization of low back pain-related functional impairment, although a subset of patients continue to suffer both pain and functional impairment. Ideally, patients at higher risk of poor outcome should be targeted for close follow-up with the goal of preventing the transition from acute to chronic pain. However, it remains difficult to predict which ED patients with acute low back pain are at risk of poor outcomes.(20)

Our data contribute to a growing body of literature suggesting that, in general, combinations of medications do not improve low back pain. We have demonstrated previously that adding cyclobenzaprine, oxycodone/acetaminophen, diazepam or corticosteroids(13) to naproxen is unlikely to benefit the patient presenting with acute low back pain.(3, 4) It is also true that acetaminophen is of no benefit for patients with non-radicular low back pain (15). Complementary therapies, including acupuncture,(21) yoga,(22) and massage(23) may be offered but have been inadequately studied to determine efficacy in an acute low back pain population. Spinal manipulation is unlikely to benefit ED patients with acute low back pain who are given a prescription for an analgesic medication.(24) Physical therapy too is unlikely to benefit patients in an acute time frame.(24) Emergency physicians should counsel their patients that passage of time will bring improvement and eventual relief to most individuals.

Participation in this study did not commence until an individual was ready for discharge from the ED. Therefore, we do not know if these skeletal muscle relaxants, when administered acutely in the ED, increase the likelihood of discharge among those patients who arrived with marked functional impairment due to low back pain. Also, we excluded from participation those patients with chronic or frequent episodic low back pain. Therefore, the role of these medications for these patients is unknown.

In conclusion, neither orphenadrine nor methocarbamol confer any additional analgesic or functional effectiveness when added to naproxen for the treatment of non-radicular, non-traumatic acute low back pain.

Figure 2.

Figure 2a. Spaghetti pot of RMDQ scores over time. Placebo arm

Figure 2b. Spaghetti plot of RMDQ scores over time. Orphenadrine arm

Figure 2c. Spaghetti plot of RMDQ scores over time. Methocarbamol arm

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported in part by the Harold and Muriel Block Institute for Clinical and Translational Research at Einstein and Montefiore grant support (UL1TR001073)

Appendix 1. Roland Morris low back pain disability questionnaire

| 1. | Over the last 24 hours, I have stayed home most of the time because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 2. | Over the last 24 hours, I changed position frequently to try to get my back comfortable: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 3. | Over the last 24 hours, I walked more slowly than usual because of my back: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 4. | Over the last 24 hours, I have not been doing any jobs that I usually do around the house because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 5. | Over the last 24 hours, I used a handrail to get upstairs because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 6. | Over the last 24 hours, I lay down to rest more often because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 7. | Over the last 24 hours, I have had to hold on to something to get out of an easy chair because of my back pain | No0 | Yes1 |

| 8. | Over the last 24 hours, I have tried to get other people to do things for me because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 9. | Over the last 24 hours, I got dressed more slowly than usual because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 10. | Over the last 24 hours, I only stood up for short periods of time because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 11. | Over the last 24 hours, I tried not to bend or kneel down because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 12. | Over the last 24 hours, I found it difficult to get out of a chair because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 13. | Over the last 24 hours, my back was painful almost all of the time: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 14. | Over the last 24 hours, I found it difficult to turn over in bed because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 15. | Over the last 24 hours, my appetite was not very good because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 16. | Over the last 24 hours, I have had trouble putting on my socks ( or stockings) because of the pain in my back or leg: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 17. | Over the last 24 hours, I could only walk short distances because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 18. | Over the last 24 hours, I slept less well because of my back: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 19. | Over the last 24 hours, I got dressed with the help of someone else because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 20. | Over the last 24 hours, I sat down for most of the day because of my back: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 21. | Over the last 24 hours, I avoided heavy jobs around the house because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

| 22. | Over the last 24 hours, I was more irritable and bad tempered with people than usual because of my back pain, | No0 | Yes1 |

| 23. | Over the last 24 hours, I went upstairs more slowly than usual because of my back pain | No0 | Yes1 |

| 24. | Over the last 24 hours, I stayed in bed most of the time because of my back pain: | No0 | Yes1 |

Appendix 2. Adverse medication effects

| Adverse event | Naproxen + placebo (n=79) | Naproxen + orphenadrine (n=80) | Naproxen + methocarbamol (n=81) | Difference between orphenadrine vs placebo | Difference between methocarbamol vs placebo | Difference between orphenadrine vs methocarbamol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95%CI) | ||||||

| Any adverse event | 8% (−3, 19%) | 1% (−11, 14%) | 9% (−2, 20%) | |||

| No | 62 (83%) | 67 (91%) | 61 (81%) | |||

| Yes | 13 (17%) | 7 (9%) | 14 (19%) | |||

| missing | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Drowsy1 | 4% (−5, 13%)* | 11% (0, 21%)* | 7% (−5, 18%)* | |||

| No | 43 (57%) | 41 (55%) | 38 (51%) | |||

| A little | 27 (36%) | 25 (34%) | 24 (32%) | |||

| A lot | 5 (7%) | 8 (11%) | 13 (17%) | |||

| missing | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Dizzy1 | 1% (−4, 7%)* | 3% (−4, 9%)* | 1% (−6, 8%)* | |||

| No | 63 (84%) | 59 (80%) | 61 (81%) | |||

| A little | 10 (13%) | 12 (16%) | 10 (13%) | |||

| A lot | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (5%) | |||

| missing | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Stomach irritation1 | 3% (−2, 8%)* | 4% (−2, 10%)* | 1% (−6, 8%)* | |||

| No | 63 (84%) | 65 (88%) | 65 (87%) | |||

| A little | 11 (15%) | 6 (8%) | 6 (8%) | |||

| A lot | 1 (1%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (5%) | |||

| missing | 4 | 6 | 6 | |||

At the seven day follow-up, study participants were asked specifically whether or not they experienced dizziness, drowsiness, and stomach irritation. They were asked to choose among the following options: “no,” “a little,” “a lot.”

No & A little versus A lot

Appendix 3. An assessment of blinding

As part of the one week follow-up phone call, study participants were asked, “Do you think you were given the real muscle relaxer or placebo? Responses are tabulated below.

| Response | Naproxen +Placebo (n=79) | Naproxen + Orphenadrine (n=80) | Naproxen + Methocarbamol (n=81) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I think I was given placebo | 9 (12%) | 10 (13%) | 11 (14%) |

| I think I was given a muscle relaxer | 35 (47%) | 40 (51%) | 31 (40%) |

| I’m not sure | 31 (41%) | 28 (36%) | 36 (46%) |

| Missing | 4 | 2 | 3 |

Appendix 4. Stated reason why patients would not want to receive the same medication combination

1 week after ED discharge, patients were asked if they would want to receive the same medication combination during a subsequent visit to the ED for low back pain. Those who said “No” or “Not sure” were asked why.

Naproxen + placebo

Because I’m still in pain.

Didn’t help much

Didn’t really work

I am in severe pain.

I think I got placebo. The medication is not working. I’m still in pain.

I want stronger meds

It help more.

Medication did not work for me. I took Aleve and felt better.

Medication is not working well for me

Medications are too strong

No me ayudo con el dolor.

Not enough relief

Not helping for long enough

Not sure if there could be a different option

Not working i am still in pain

Not working much

I believe the back pain went away on its own. I only took the medication twice and when I took the medication it didn’t help as much as I thought it would.

I want to take something a little stronger.

Really didn’t help.

Sleepy and drowsiness.

The medication did not make me feel better.

The naproxen worked. I read the side effects of study med and decided not to take it.

I did not like the side effects: drowsiness and sleepy.

Too drowsy

Naproxen + orphenadrine

I didn’t like how it made me feel and didn’t help much. Too drowsy & itch

It got me way too sleepy and I didn’t like the feeling. I could not focus

Because I felt sleepy and also palpitations and SOB.

Because the medication did not help me. The medication did not work and I’m still severe pain.

Because the medication did not help me with my back pain.

Because the medication did not work well. (I’m still with mild pain)

Didn’t help as much

Didn’t help much

Does not help

I need stronger meds

Vomiting after 2nd day.

I just did not want to take experimental meds.

Medication didn’t work for me.

Medications did not work for me

Normally Aleve works for me

Not taking pain away.

Not work.

Uncomfortable taking the muscle relaxer due to not being FDA approved for this condition.

I do not like taking pills so only took when needed.

Something a little stronger

Still in pain

It was not helping

The medications didn’t work. I had to come back to the ED 3 days later. I was still in pain. I was taking the naproxen 2× a day and study med 2× a day. It didn’t help.

The medication effected my stomach.

Still in pain. The medication does not work. It did not help with the pain. The medication makes me feel sleepy.

Naproxen + methocarbamol

I did not think it was necessary to take those medications. After I got medicated in the emergency the pain got better.

Because I do not know if there is something better.

Because I don’t want to received a placebo medication.

Because I’m still in pain. I would like a medication take away my back pain

Because my doctor change my medications.

Because the medication did not help me and also I don’t have any muscles spasm.

Because the medication did not work. I took another medication: Motrin and Tylenol.

Because the medication does not work. I’m still have pain.

Didnt take away the pain 100%

Drowsy

it relaxes me does not take away pain

It’s not helping me at all.

Made me very nauseous and dizzy.

Naproxen does not help with the pain and also the muscle relaxer medication does not improve the pain.

No, the medication makes me drowsy.

Not helping

Not helping the pain just making me sleepy

Patient only took Naproxen didn’t feel comfortable with the study medication.

PCP told me it was not good.

Stomach pain

The medication didn’t help and I had to go back to the ER.

The medication didn’t help.

Did not take study medication. Taking Tramadol and Diazepam.

I drive for a living and I’ve been working and I was unable to take the medication during my shift.

I still have the pain. I do not like the medication. I think I got the placebo medication. It’s not working.

I still have the low back pain. The medication does not help.

Appendix 5. Three month outcomes

| Outcome variable | Naproxen + placebo (n=79) | Naproxen + orphenadrine (n=80) | Naproxen + methocarbamol (n=81) | Difference between orphenadrine and placebo | Difference between methocarbamol and placebo | Difference between orphenadrine and methocarbamol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95%CI) | ||||||

| Median RMDQ (IQR) | 0 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 13) | 0 (0, 8) | 1.8 (−0.7, 4.2)* | 1.1 (−1.3, 3.5)* | 0.7 (−2.0, 3.3) * |

| missing | 11 | 11 | 11 | |||

| Worst low back pain during previous 72 hours | 2% (−11, 15%) | 2% (−11%, 16%) | 4% (−9, 17% - |

|||

| Mild/none | 55 (81%) | 58 (83%) | 55 (79%) | |||

| Moderate/severe | 13 (19%) | 12 (17%) | 15 (21%) | |||

| missing | 11 | 10 | 11 | |||

RMDQ: Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. This is a 24 item instrument measuring low back pain related functional impairment. On this instrument, 0 represents no low back pain related functional impairment and 24 represents maximum functional impairment.

mean difference (95%CI)

Appendix 6. A listing of all three month RMDQ scores

| RMDQ score | Placebo | Orphenadrine | Methocarbamol |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 39 (57%) | 37 (54%) | 38 (54%) |

| 1 | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) |

| 2 | 5 (7%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) |

| 3 | 3 (4%) | 0 | 2 (3%) |

| 4 | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3%) |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| 7 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| 8 | 0 | 3 (4%) | 1 (1%) |

| 9 | 3 (4%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| 10 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| 14 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| 15 | 3 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 0 |

| 16 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| 17 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) |

| 18 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| 19 | 0 | 3 (4%) | 0 |

| 20 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) |

| 21 | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) |

| 22 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| 23 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 |

| 24 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

Appendix 7. Clinical studies of methocarbamol for musculoskeletal pain

| Author, year | Setting, population, N | Methocarbamol dosing | Comparator | Acute outcomes | Longer term outcomes | Adverse medication effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tisdale, 1975 | Outpatient, muscle spasm due to trauma or inflammation, ≤14 days, N=180 | 2000mg every 6 hours | Placebo | 48 hours improvement in pain, functional impairment and daily activities > placebo | 7–9 day improvement in pain, functional limitations, daily activities, desire to take same medication again | 11% report nuisance side effects |

| Emrich, 2015 | Acute back pain, N=202 | 1500mg every 8 hours | Placebo | 44% versus 18% achieved pain relief | Not reported | 5% reported nuisance side effects |

Appendix 8. Clinical studies of orphenadrine for musculoskeletal pain

| Author, year | Setting, population, N | Orphenadrine dosing | Comparator | Acute outcomes | Adverse effects of orphenadrine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hingorani, 1971 | Inpatient, acute or acute-on-chronic lumbar pain, 99 | Orphenadrine 70mg + paracetamol 900mg TID | Aspirin 100mg TID | No difference in pain improvement. Fewer patients in orphenadrine group required additional medication | Self –limited side effects in 12% |

| Tervo, 1976 | Orthopedics/trauma clinic, acute lumbago, 50 | Orphenadrine 70mg + paracetamol 900mg TID | Paracetamol 900mg TID | 7–10 days: Fewer days of disability | Orphenadrine/APAP: 1 patient with nausea, 1 patient difficulties with accomodation |

| Gold, 1978 | Outpatient, acute low back pain, 60 | 100mg BID | Phenobarbital 32mg BID Placebo |

Reduced pain at 48 hours > comparators | Self limited side effects in 25% |

| Klinger, 1988 | Military low back pain clinic, Low back train with pain, spasm, limited ROM, 80 | 60mg IV | Placebo | Substantially greater relief of pain and range of motion | Mild-moderate in intensity and resolved without sequelae |

Footnotes

We will present these data at the American College of Emergency Physicians research forum in Washington DC in October, 2017

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

BWF, EJG conceived the study. BWF, DC, MD, AN, SP, DW reviewed the literature in preparation for the trial. BWF, DC, CS, EJG designed the trial. BWF, EI, CS supervised the conduct of the trial and data collection. BWF, EI, DC, AN, SP, DW managed the data. BWF, DC, MD, SP, DW analyzed the data. BWF, DC, AN drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. BWF takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

The study was registered online at http://clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02665286).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Friedman BW, Chilstrom M, Bijur PE, Gallagher EJ. Diagnostic testing and treatment of low back pain in United States emergency departments: a national perspective. Spine (Phila Pa. 1976;35(24):E1406–11. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d952a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman BW, O’Mahony S, Mulvey L, Davitt M, Choi H, Xia S, et al. One-week and 3-month outcomes after an emergency department visit for undifferentiated musculoskeletal low back pain. Annals of emergency medicine. 2012;59(2):128–33. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman BW, Dym AA, Davitt M, Holden L, Solorzano C, Esses D, et al. Naproxen With Cyclobenzaprine, Oxycodone/Acetaminophen, or Placebo for Treating Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1572–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman BW, Irizarry E, CS, Khankel N, Zapata J, Zias E, et al. Diazepam is no better than placebo when added to naproxen for acute low back pain. Annals of emergency medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain: an updated Cochrane review. Spine. 2008;33(16):1766–74. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817e69d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman BW, Chilstrom M, Bijur PE, Gallagher EJ. Diagnostic testing and treatment of low back pain in United States emergency departments: a national perspective. Spine. 2010;35(24):E1406–11. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d952a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou R, Peterson K. Drug Class Review: Skeletal Muscle Relaxants: Final Report. Portland (OR): 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simons DG, Mense S. Understanding and measurement of muscle tone as related to clinical muscle pain. Pain. 1998;75(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Middleton RS. A comparison of two analgesic muscle relaxant combinations in acute back pain. Br J Clin Pract. 1984;38(3):107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sica DA, Comstock TJ, Davis J, Manning L, Powell R, Melikian A, et al. Pharmacokinetics and protein binding of methocarbamol in renal insufficiency and normals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;39(2):193–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00280060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tisdale SA, Jr, Ervin DK. A controlled study of methocarbamol (Robaxin) in acute painful musculoskeletal conditions. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 1975;17(6):525–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deyo RA, Battie M, Beurskens AJ, Bombardier C, Croft P, Koes B, et al. Outcome measures for low back pain research. A proposal for standardized use. Spine. 1998;23(18):2003–13. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809150-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman BW, Holden L, Esses D, Bijur PE, Choi HK, Solorzano C, et al. Parenteral corticosteroids for Emergency Department patients with non-radicular low back pain. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2006;31(4):365–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stratford PW, Binkley J, Solomon P, Finch E, Gill C, Moreland J. Defining the minimum level of detectable change for the Roland-Morris questionnaire. Physical therapy. 1996;76(4):359–65. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.4.359. discussion 66–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emrich OM, Milachowski KA, Strohmeier M. Methocarbamol in acute low back pain. A randomized double-blind controlled study. MMW Fortschr Med. 2015;157(Suppl 5):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s15006-015-3307-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hingorani K. Diazepam in backache. A double-blind controlled trial. Ann Phys Med. 1966;8(8):303–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tervo T, Petaja L, Lepisto P. A controlled clinical trial of a muscle relaxant analgesic combination in the treatment of acute lumbago. Br J Clin Pract. 1976;30(3):62–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gold RH. Orphenadrine Citrate: Sedative or Muscle Relaxant? Clinical Therapeutics. 1978;1(6):451–3. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klinger NM, Wilson RR, Kanniainen CM, Wagenknecht KA, Re ON, Gold RH. Intravenous orphenadrine for the treatment of lumbar paravertebral muscle strain. Current Therapeutic Research. 1988;43(2):247–54. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Friedman BW, Gensler S, Yoon A, Nerenberg R, Holden L, Bijur PE, et al. Predicting three-month functional outcomes after an ED visit for acute low back pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(2):299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furlan AD, van Tulder M, Cherkin D, Tsukayama H, Lao L, Koes B, et al. Acupuncture and dryneedling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2005;30(8):944–63. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000158941.21571.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(5):450–60. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31825e1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Furlan AD, Imamura M, Dryden T, Irvin E. Massage for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane Back Review Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(16):1669–84. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ad7bd6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rothberg S, Friedman BW. Complementary therapies in addition to medication for patients with nonchronic, nonradicular low back pain: a systematic review. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]