Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are widespread environmental contaminants that occur in complex mixtures. Several PAHs are known or suspected mutagens and/or carcinogens, but developmental toxicity data is lacking for PAHs, particularly their oxygenated and nitrated derivatives. Such data is necessary to understand and predict the toxicity of environmental mixtures. 123 PAHs were assessed for morphological and neurobehavioral effects for a range of concentrations between 0.1 and 50 μM, using a high-throughput early life stage zebrafish assay, including 33 parent, 22 nitrated, 17 oxygenated, 19 hydroxylated, 14 methylated, 16 heterocyclic, and 2 aminated PAHs. Additionally, each PAH was evaluated for AHR activation, by assessing CYP1A protein expression using whole animal immunohistochemistry (IHC). Responses to PAHs varied in a structurally-dependent manner. High-molecular weight PAHs were significantly more developmentally toxic than the low-molecular weight PAHs, and CYP1A expression was detected in 5 distinct tissues, including vasculature, liver, skin, neuromasts and yolk.

Introduction

Characterized by two or more fused aromatic rings (Ravindra et al. 2008), PAHs are produced through pyrogenic (combustion derived), petrogenic (petroleum derived) and biogenic processes, and can include a variety of heteroatomic substitutions on or within the ring system. Non-occupational human exposure primarily occurs through the diet, especially ingestion of smoked and grilled meats and vegetables (Bansal and Kim 2015), through direct or secondhand inhalation of tobacco smoke (Ramos and Moorthy 2005; Rodgman et al. 2000), inhalation of polluted air, or through contact with contaminated soils and water (Goldman et al. 2001; Lundstedt et al. 2007). Common sources of PAHs in the environment include anthropogenic activity like petroleum and plant based fuel use, and natural sources such as oil seeps, forest fires, and volcanic emissions (Li et al. 2002; Zhang and Tao 2009). Like the parent compounds, polar PAH derivatives can form directly through incomplete combustion. However, PAH derivatives can also be formed through a variety of abiotic and biotic processes, including reactions with NOx, O3, and OH radicals in the atmosphere (Cochran et al. 2016; Jariyasopit et al. 2014a; Jariyasopit et al. 2014b; Lundstedt et al. 2007), and biotic metabolism (Shailaja et al. 2006; Xue and Warshawsky 2005). Parent and PAH derivatives are found in complex mixtures in the environment, but modelling the toxicity of mixtures is impractical without an understanding of the potential developmental effects of an individual PAH. The most sensitive life stage to chemical bioactivity is during development when all cellular networks are active. Therefore, development is a critical period of concern for exposure to PAHs, which are known to readily cross the placental barrier (Perera et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2017).

Growing evidence associates developmental PAH exposure with adverse effects in early and later life stages. Increased developmental PAH exposure in humans has been correlated with increased childhood obesity (Rundle et al. 2012) and ADHD rates (Perera et al. 2014), and decreased IQ (Perera et al. 2009; Perera et al. 2006), height gain, birth weight, birth length, and head circumference in epidemiological studies (Perera et al. 1998). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) dependent and independent cardiovascular effects, and oxidative stress are well studied components of PAH toxicity (Burczynski et al. 1999; Incardona et al. 2004; Incardona et al. 2011; Knecht et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2009; Scott et al. 2011), and recent studies indicate that persistent neurodevelopmental effects are also important aspects of PAH toxicity (Chen et al. 2012; Crepeaux et al. 2012; Crepeaux et al. 2013; Incardona et al. 2004; Incardona et al. 2006; Knecht et al. 2017; Vignet et al. 2014a; Vignet et al. 2014b). In light of this, it is clear that PAHs have distinct bioactivities that cannot be summarized by a single mechanism of action.

Developmental toxicity data and regulations on PAHs have primarily come from studies of benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), and to a lesser extent from the other 27 priority PAHs designated by the US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) (Ostrowski et al. 1999; USEPA 2010). The 27 PAHs included in the USEPA’s Relative Potency Factor (RPF) approach were selected based on their known carcinogenic potential relative to B[a]P (USEPA 2010), and are limited to parent (unsubstituted) compounds. This means that hundreds of substituted PAHs (e.g. oxygenated, hydroxylated, nitrated, methylated, alkylated, and heterocyclic) are not represented among the developmental toxicity data. Additionally, the RPF PAHs include few high molecular weight PAHs, many of which are known or suspected carcinogens. Therefore, current developmental toxicity data does not effectively capture the structural variability of substituted PAHs, and likely does not capture the complete range of PAH developmental toxicity. Efforts to model PAH toxicity have primarily focused on log Kow as a predictive tool for PAH bioavailability and bioactivity (Billiard et al. 2008; Boese et al. 1999; Mathew et al. 2008; Sabljic 2001) with considerably more success for the former than the latter parameter.

The zebrafish has the distinct advantage of being the only vertebrate model amenable to high throughput testing of a wide range of PAHs for effects on complex endpoints, and have demonstrated concordance with a variety of mammalian and in vitro models for numerous compounds (Boyd et al. 2016; Volz et al. 2015). Zebrafish embryos develop externally, rapidly and are transparent, enabling quick assessment of developmental effects, especially organ development and neurobehavioral effects (Dooley and Zon 2000; Peal et al. 2010). Their small size allows testing of compounds in small volumes, which is ideal for compounds that are difficult to synthesize or obtain in large volumes. Zebrafish are also amenable to molecular and cell culture techniques, making them an ideal model to investigate molecular mechanisms of toxicity. Zebrafish fully support phase I and phase II detoxification pathways by 5 days post fertilization (Goldstone et al. 2010; Kurogi et al. 2013; Le Fol et al. 2017), allowing them to reveal developmental toxicity that is metabolism-dependent. This is particularly useful for evaluating PAH toxicity, which depends, in most cases, on metabolic activation (Incardona et al. 2006; Xue and Warshawsky 2005).

This paper represents the most comprehensive in vivo characterization of PAH and substituted PAH developmental toxicity to date. Morphological and neurobehavioral effects were assessed for 123 commercially available and custom-synthesized PAH standards using the embryonic zebrafish model. They included: 33 parent, 22 nitrated, 17 oxygenated, 19 hydroxylated, 14 methylated, 16 heterocyclic, and 2 aminated (potential metabolites of nitrated PAHs) PAHs. These structures were selected for broad coverage of environmental and metabolic byproduct prevalence. Hydroxy-PAHs were emphasized due to their ready formation as metabolites in fish and humans following PAH exposure, and by fossil fuel combustion and environmental oxidation (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009; Luderer et al. 2017; Pulster et al. 2017; Simoneit et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2017). Furthermore, cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A (CYP1A) expression patterns were characterized for each compound as an indicator for AhR activation. Results were compared with predicted log Kow values to assess the predictive power of that method.

Methods

Chemicals

Analytical grade standards were obtained from several vendors including: AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA), Alfa Aesar (Tewksbury, MA, USA), Chiron Chemicals (Hawthorn, Australia), Combi-Blocks (San Diego, CA, USA), Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM) (Geel, Belgium), MRIGlobal (Kansas City, MO, USA), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SCB) (Dallas, TX, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO, USA), Sigma-Aldrich Rare Chemical Library (Sigma-Aldrich RCL) (Saint Louis, MO, USA), and Toronto Research Chemicals (TRC) (Toronto, ON, Canada). 3,7-dinitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene and 7-nitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene were synthesized in-house (Jariyasopit et al. 2014a). In all, standards for 123 PAHs and PAH derivatives were obtained and dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to make stock solutions (Table 1).

Table 1.

PAHs tested alphabetically by class, CAS registration number, supplier, percent purity, working stock concentration in 100% DMSO, and concentration used for immunohistochemistry evaluations

| PAH | CASRN | Supplier | Purity (%) | Nominal Stock Concentration (mM) | IHC Concentration (uM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | |||||

| Acenaphthene | 83-32-9 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| Acenaphthylene | 208-96-8 | AccuStandard | 99.2 | 10 | 50 |

| Anthracene | 120-12-7 | AccuStandard | 99.6 | 10 | 50 |

| Anthanthrene | 191-26-4 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 15.8 |

| Benzo[a]pyrene | 50-32-8 | Sigma Aldrich | 96 | 5 | 50 |

| Benzo[b]fluoranthene | 205-99-2 | AccuStandard | 99.2 | 10 | 50 |

| Benzo[b]fluorene | 243-17-4 | AccuStandard | 96.5 | 10 | 50 |

| Benzo[e]pyrene | 192-97-2 | AccuStandard | 99.9 | 10 | 8.9 |

| Benzo[g,h,i]perylene | 191-24-2 | AccuStandard | 98.9 | 1 | 2.8 |

| Benzo[j]fluoranthene | 205-82-3 | AccuStandard | 98.1 | 10 | 50 |

| Benzo[k]fluoranthene | 207-08-9 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 8.9 |

| Chrysene | 218-01-9 | AccuStandard | 99.8 | 10 | 50 |

| Coronene | 191-07-1 | AccuStandard | 100 | 1 | 8.9 |

| Dibenz[a,c]anthracene | 215-58-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 50 |

| Dibenz[a,h]anthracene | 53-70-3 | AccuStandard | 99 | 1 | 10 |

| Dibenzo[a,h]pyrene | 189-64-0 | AccuStandard | 99.9 | 1 | 10 |

| Dibenzo[a,i]pyrene | 189-55-9 | AccuStandard | 99.8 | 1 | 5 |

| Dibenzo[a,k]fluoranthene | 84030-79-5 | Chiron | 99.9 | 1 | 10 |

| Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene | 191-30-0 | AccuStandard | 99 | 10 | 35.6 |

| Dibenzo[b,k]fluoranthene | 205-97-0 | Chiron | ** | 1 | 10 |

| Dibenzo[j,l]fluoranthene | 203-18-9 | Chiron | ** | 1 | 10 |

| Fluoranthene | 206-44-0 | AccuStandard | 97.2 | 10 | 50 |

| Fluorene | 86-73-7 | AccuStandard | 99.1 | 10 | 50 |

| Indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene | 193-39-5 | AccuStandard | 99.2 | 1 | 10 |

| Naphthalene | 91-20-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 50 |

| Naphtho[1,2-b]fluoranthene | 111189-32-3 | Chiron | 98.8 | 1 | 10 |

| Naphtho[2,3-b]fluoranthene | 206-06-4 | Chiron | 99.8 | 1 | 10 |

| Naphtho[2,3-e]pyrene | 193-09-9 | Chiron | 99 | 10 | 10 |

| Naphtho[2,3-j]fluoranthene | 205-83-4 | Chiron | 99.8 | 1 | 10 |

| Naphtho[2,3-k]fluoranthene | 207-18-1 | Chiron | 99.8 | 1 | 10 |

| Phenanthrene | 65996-93-2 | AccuStandard | 99.5 | 10 | 50 |

| Pyrene | 129-00-0 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 40 |

| Triphenylene | 217-59-4 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 5 |

| Aminated | |||||

| 1-aminopyrene | 1606-67-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 6.4 |

| 9-aminophenanthrene | 947-73-9 | Sigma Aldrich | 96 | 10 | 6.4 |

| Methylated | |||||

| 1,2-dimethylnaphthalene | 573-98-8 | AccuStandard | 94 | 10 | 50 |

| 1,4-dimethylnaphthalene | 571-58-4 | AccuStandard | 95.7 | 10 | 50 |

| 1,5-dimethylnaphthalene | 571-61-9 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| 1,6-dimethylnaphthalene | 575-43-9 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| 1,8-dimethylnaphthalene | 569-41-5 | AccuStandard | 100 | 9.7 | 50 |

| 1-methylnaphthalene | 90-12-0 | AccuStandard | 99.7 | 15.7 | 50 |

| 2,3-dimethylanthracene | 613-06-9 | AccuStandard | 98.9 | 10 | 5 |

| 2,6-dimethylnaphthalene | 581-42-0 | AccuStandard | 100 | 8.7 | 50 |

| 2-methylanthracene | 613-12-7 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| 2-methylnaphthalene | 91-57-6 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene | 1576-67-6 | AccuStandard | 99.3 | 10 | 50 |

| 6-methylchrysene | 1705-85-7 | AccuStandard | 98.8 | 10 | 8.9 |

| 9-methylanthracene | 779-02-2 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| Retene | 483-65-8 | SCB | 98 | 10 | 15.8 |

| Oxygenated | |||||

| 1,2-naphthoquinone | 524-42-5 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 3.5 |

| 1,4-anthraquinone | 635-12-1 | Alfa Aesar | 94 | 10 | 0.5 |

| 1,4-phenanthrenedione | 569-15-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 100 | 10 | 0.08 |

| 2-ethylanthraquinone | 84-51-5 | Sigma Aldrich | 98.6 | 10 | 11.2 |

| 4H-cyclopenta[def]phenanthren-4-one | 5737-13-3 | Chiron | 99.4 | 10 | 0.4 |

| 5,12-naphthacenequinone | 1090-13-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 2 |

| 6H-benzo[cd]pyren-6-one | 3074-00-8 | IRMM | 98.8 | 1 | 2 |

| 9-anthracene carboxylic acid | 723-62-6 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 50 |

| 9,10-phenanthrenequinone | 84-11-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 0.16 |

| 9-fluorenone | 486-25-9 | Sigma Aldrich | 97.5 | 10 | 50 |

| 11H-benzo[b]fluoren-11-one | 3074-03-1 | Combi-Blocks | 95 | 10 | 50 |

| Acenaphthenequinone | 82-86-0 | Sigma Aldrich | 90 | 10 | 2 |

| Anthraquinone | 84-65-1 | Sigma Aldrich | 99.9 | 10 | 50 |

| Benzanthrone | 82-05-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 98.8 | 10 | 2 |

| Benzo[c]phenanthrene[1,4]quinone | 109699-80-1 | Chiron | 99 | 10 | 0.4 |

| Perinaphthenone | 548-39-0 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 0.4 |

| Pyrene-4,5-dione | 6217-22-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 100 | 10 | 0.08 |

| Hydroxylated | |||||

| 1,3-dihydroxynaphthalene | 132-86-5 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 2 |

| 1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene | 83-56-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 2 |

| 1,6-dihydroxynaphthalene | 575-44-0 | Sigma Aldrich | 98.5 | 10 | 2 |

| 1-hydroxyindeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene | 193-39-5 | MRIGlobal | >98 | 10 | 10 |

| 1-hydroxynaphthalene | 90-15-3 | Sigma Aldrich | >99 | 10 | 35.6 |

| 1-hydroxyphenanthrene | 2433-56-9 | TRC | 98.0 | 10 | 5 |

| 1-hydroxypyrene | 5315-79-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 99.8 | 10 | 5 |

| 2,3-dihydroxynaphthalene | 92-44-4 | Sigma Aldrich | 98 | 5 | 2 |

| 2,7-dihydroxynaphthalene | 582-17-2 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 2 |

| 2-hydroxynaphthalene | 135-19-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 99.0 | 10 | 11.2 |

| 3-hydroxybenz[a]anthracene | 4834-35-9 | TRC | 99.8 | 10 | 11.2 |

| 3-hydroxybenzo[e]pyrene | 77508-02-2 | MRIGlobal | 99.0 | 10 | 11.2 |

| 3-hydroxyfluoranthene | 17798-09-3 | MRIGlobal | 96% | 10 | 5 |

| 3-hydroxyfluorene | 6344-67-8 | Sigma-Aldrich RCL | ** | 10 | 11.2 |

| 3-hydroxyphenanthrene | 605-87-8 | MRIGlobal | 98.0 | 10 | 1 |

| 4-hydroxychrysene | 63019-40-9 | MRIGlobal | >99 | 10 | 1 |

| 4-hydroxyphenanthrene | 7651-86-7 | TRC | 98 | 10 | 5 |

| 9-hydroxyphenanthrene | 484-17-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 92.8 | 10 | 5 |

| 10-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene | 56892-31-0 | MRIGlobal | 99 | 10 | 2 |

| Nitrated | |||||

| 1,3-dinitropyrene | 75321-20-9 | AccuStandard | 99.5 | 1 | 6.4 |

| 1,6-dinitropyrene | 42397-64-8 | AccuStandard | 99.4 | 1 | 3.6 |

| 1,8-dinitropyrene | 42397-65-9 | AccuStandard | 95.2 | 1 | 6.4 |

| 1-nitronaphthalene | 86-57-7 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 64 |

| 1-nitropyrene | 5522-43-0 | Sigma Aldrich | 98 | 10 | 64 |

| 2-nitroanthracene | 3586-69-4 | AccuStandard | 99.8 | 10 | 64 |

| 2-nitrofluoranthene | 13177-29-2 | Chiron | 99 | 10 | 64 |

| 2-nitrofluorene | 607-57-8 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 64 |

| 2-nitronaphthalene | 581-89-5 | AccuStandard | 94.2 | 10 | 64 |

| 2-nitropyrene | 789-07-1 | Chiron | 99.9 | 10 | 64 |

| 3,7-dinitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene | NA | In-House | 94 | 10 | 64 |

| 3-nitrobenzanthrone | 17117-34-9 | Chiron | 99.8 | 1 | 1.14 |

| 3-nitrofluoranthene | 892-21-7 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 64 |

| 3-nitrophenanthrene | 17024-19-0 | AccuStandard | 99.8 | 10 | 64 |

| 5-nitroacenaphthalene | 602-87-9 | AccuStandard | 81.5 | 10 | 64 |

| 6-nitrobenzo[a]pyrene | 63041-90-7 | Sigma Aldrich | 99.18 | 10 | 64 |

| 6-nitrochrysene | 7496′-02-08 | AccuStandard | 99.6 | 10 | 64 |

| 7-nitrobenz[a]anthracene | 20268-51-3 | AccuStandard | 99 | 10 | 64 |

| 7-nitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene | NA | In-House | 98 | 10 | 64 |

| 9-nitroanthracene | 602-60-8 | AccuStandard | 99.2 | 10 | 64 |

| 9-nitrophenanthrene | 954-46-1 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 6.4 |

| 9-anthracene carbonitrile | 723-62-6 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 50 |

| Heterocyclic | |||||

| 2,8-dinitrodibenzothiophene | 109041-38-5 | AccuStandard | 99 | 1 | 6.4 |

| 2-methylbenzofuran | 4265-25-2 | Sigma Aldrich | 96 | 10 | 50 |

| 2-nitrodibenzothiophene | 6639-36-7 | AccuStandard | 100 | 10 | 6.4 |

| 3-nitrodibenzofuran | 5410-97-9 | AccuStandard | 99.2 | 10 | 64 |

| 4H-cyclopenta[lmn]phenanthridine-5,9-dione | 61479-80-9 | SCB | 95 | 10 | 5 |

| 5,6-benzoquinoline | 85-02-9 | AccuStandard | 99 | 10 | 11.2 |

| 8-methylquinoline | 611-32-5 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 50 |

| Acridine | 260-94-6 | AccuStandard | 99.3 | 10 | 23.4 |

| Carbazole | 86-74-8 | AccuStandard | 99.7 | 10 | 35.6 |

| Chromone | 491-38-3 | Sigma Aldrich | 99 | 10 | 2 |

| Dibenzofuran | 132-64-9 | Sigma Aldrich | 98.6 | 10 | 50 |

| Indole | 120-72-9 | AccuStandard | 99 | 10 | 50 |

| Quinoline | 91-22-5 | AccuStandard | 96.5 | 10 | 50 |

| Thianaphthene | 95-15-8 | Sigma Aldrich | 98 | 10 | 50 |

| Xanthene | 92-83-1 | AccuStandard | 99 | 10 | 50 |

| Xanthone | 90-47-1 | Sigma Aldrich | 97 | 10 | 2 |

Purity and identity have not been verified

Zebrafish Husbandry

Tropical 5D zebrafish were maintained at the Oregon State University Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory (SARL, Corvallis, OR), under a 14:10 hour light/dark cycle. Fish were raised in densities of ~500 fish/50-gallon tank at 28°C in recirculating filtered water supplemented with Instant Ocean salts. Spawning funnels were placed in tanks the night prior, and the following morning embryos were collected, staged and maintained in an incubator at 28°C (Kimmel et al. 1995).

Exposures

The chorions of 4 hours post fertilization (hpf) embryos were enzymatically removed using a custom automated dechorionator and at 6 hpf embryos were placed one per well in round bottom 96-well plates prefilled with 100 μL EM, using automated embryo placement systems (Mandrell et al. 2012). A Hewlett Packard D300e chemical dispenser was used to dispense 100% DMSO stocks into 2 replicate exposure plates. Final DMSO concentrations were normalized to 1% (vol/vol), and gently shaken by the chemical dispenser during dispensing. Plates were sealed with parafilm to minimize evaporation, and shaken overnight at 235 rpm on an orbital shaker at 28°C to enhance solution uniformity (Truong et al. 2016). Embryos were statically exposed until 120 hpf, and kept in a 28°C incubator for the duration of the exposure. Two test concentration lists were used, depending on the stock concentration and the percentage of DMSO tolerable to developing zebrafish. Exposure concentrations for the 10 mM and 5 mM stock solutions were: 50, 35.6, 11.2, 5, and 1 μM. Exposure concentrations for the 1 mM stock solutions were: 5, 3.56, 1.12, 0.5, and 0.1 μM. Compounds with high mortality at the 10 mM stock concentrations were rescreened at the 1 mM stock concentrations. Concentrations that had visibly precipitated out of solution by the end of the exposure were excluded from analysis.

Developmental Toxicity Screening

At 24 hpf embryos were assessed for mortality, developmental progression, notochord formation, and spontaneous motion. At 120 hpf, larvae were further assessed for 18 developmental endpoints: mortality, yolk sac edema, pericardial edema, body axis, trunk length, caudal fin, pectoral fin, pigmentation, somite, eye, snout, jaw, otolith, brain, notochord and circulatory malformations, swim bladder presence and inflation, and touch response. Responses were recorded as a binary absence or presence of an abnormal morphology for each endpoint. Lowest effect levels (LELs) were calculated for each endpoint using a binomial test to estimate significance thresholds as previously described (p<0.05) (Truong et al. 2016).

Embryonic Photomotor Response

Embryonic photomotor response (EPR) was evaluated in 24 hpf embryos using a custom-built photomotor response assay tool (PRAT) (Noyes et al. 2015). After chemical exposure, embryos were not exposed to visible light until administration of the EPR test. The test consisted of: 30 s of darkness (Background); first pulse of intense light; 9 s darkness (Excitation); second pulse of intense light; 10 s darkness (Refractory). Pixel changes between video frames were recorded to quantify total movement for each embryo across the test. Before analysis, wells with adverse effects (including mortality) observed at 24 hpf were removed. Statistical significance was assessed separately for each interval (Background, Excitation, and Refractory), using a Kolmogerov-Smirnov (KS) test (Bonferroni-corrected p value threshold = 0.05) against the vehicle control animals (Reif et al. 2016).

Larval Photomotor Response

Larval photomotor response (LPR) was evaluated in 120 hpf larvae with a light-dark cycle and video tracking software (ViewPoint Life Sciences, Lyon, France). There were a total of 4 light cycles, each light cycle consisting of 3 minutes in the light, and 3 minutes in the dark. Wells with mortality or morbidity were excluded from the data analysis. Statistical significance was quantified using a KS test (p<0.05) on measured Area Under the Curve, dividing the dark and light cycles into separate bins, and was further constrained by a 50%-fold change threshold of significance for hyper or hypoactivity.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily A (CYP1A) protein localization was performed as previously described (Mathew et al. 2006). Briefly, wild type (Tropical 5D) embryos were exposed from 6–120 hpf to the highest soluble concentration tested that did not cause significant mortality (Table 1). Two replicates of 8 larvae each were euthanized with tricaine, and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Fixed embryos were permeablized 10 minutes on ice in 0.005% trypsin, rinsed with PBS+Tween 20 (PBST) and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes. Larvae were blocked with 10% normal goat serum (NGS) in PBS+0.5% Triton X-100 (PBSTx) for 1 hour at RT, and incubated overnight in the primary antibody mouse α fish CYP1A monoclonal antibody (BiosenseLaboratories, Bergen, Norway) (1:500) in 1% NGS. Larvae were washed in PBST and incubated for 2 hours in secondary antibody (Fluor 594 goat anti-mouse, IgG). Eight embryos per treatment group were assessed by epifluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M or Keyence BZ-X700 microscope with 10× and 20× objectives and scored for the presence or absence of fluorescence in specific tissues.

Data Analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using custom code developed in R (Team 2015). The heatmap, bar plots, and pie charts were rendered using the ggplot2 package for R (Wickham 2009). Hierarchical clustering analyses were conducted using Euclidean distance-based dissimilarity matrices using a “bottom-up” approach. The Venn diagram was created using the online tool “Calculate and draw custom Venn diagrams” created by the Bioinformatics and Evolutionary Genomics group at the University of Gent. The log of the octanol-water partitioning coefficient for each chemical was estimated using EpiSuite™ KOWWIN™ v1.68.

Results

PAH Library

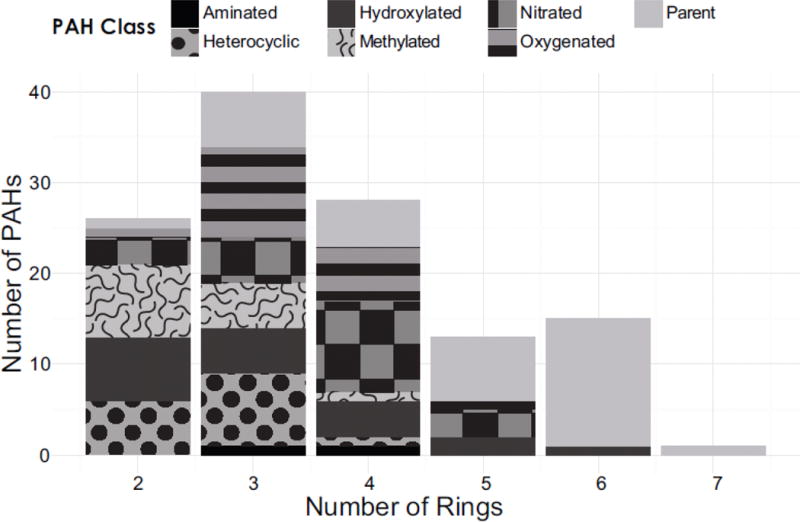

A total of 123 PAHs were selected for testing, including parent compounds and a selection of oxygenated, hydroxylated, heterocyclic, nitrated, and aminated derivatives. Selection was primarily based upon obtaining a representative variety of physicochemical properties, to capture the widest possible variety of developmental effects, while also selecting environmentally and metabolically relevant parents and derivatives. Selected compounds contained two to seven fused aromatic rings, which, due to the availability of standards, was weighted slightly towards the smaller, more water soluble structures (Fig 1). PAHs with three aromatic rings were the most represented, with a total of 40 tested. Parent PAHs were represented at every ring number, while PAH derivatives were commercially limited to compounds with 2–6 aromatic rings at the time of procurement.

Figure 1.

Summary of the PAHs evaluated.

Developmental Toxicity Profiles

Embryos were exposed to concentration ranges of each of the 123 PAHs, and were evaluated for adverse morphological effects and neurobehavioral endpoints across concentrations. The developmental toxicity profiles (Fig 2) were binned into 6 distinct groups: 1) Mortality at low concentrations and few other observed morphological effects, 2) Several, severe morphological endpoints at low concentrations, 3) Fewer morphological endpoints primarily at the two highest concentrations tested, 4) No morphological abnormalities, but LPR behavior effects, 5) No morphological abnormalities, but EPR behavior effects, 6) No observed developmental effects. The largest, Group 4, consists only of those with LPR effects, contained 57 PAHs. The next largest, Group 2, severe, varied malformations and high mortality at lower concentrations, contained 25 PAHs. The 18 PAHs of Group 3 affected a handful of non-mortality endpoints, usually at higher concentrations. The 12 PAHs of Group 1 affected mostly 24 hpf mortality at low concentrations. The 11 PAHs of Group 6 produced no adverse effects. Most compounds with an altered EPR also had other endpoints affected, but quinoline only had an observed effect on EPR (Group 5).

Figure 2.

Heirarchically clustered heatmap of lowest effect levels for developmental toxicity endpoints, and neurobehavioral assays (left 5 columns). “Any Effect” and “Any Except Mortality” (right 2 columns) are aggregates of all morphological endpoints. Darker red color denotes decreased lowest concentration of effect, and higher toxicity. Class of PAH is denoted by color in rightmost column.

PAHs within a class generally sorted into one or two of the above groups. The majority of PAHs with severe effects (Groups 1 and 2) were oxygenated, hydroxylated, or heterocyclic derivatives. The only parent compounds in these groups were dibenzo[a,l]pyrene and dibenzo[a,c]anthracene. Almost half of the unaffected Group 6 compounds were parent PAHs, the rest a mixture of nitrated and heterocyclic PAHs. Parent compounds were generally less bioactive than their oxygenated, hydroxylated, or nitrated derivatives.

Embryonic Photomotor Response (EPR)

Of the tested PAHs, 28 resulted in a significant change in EPR in at least one phase (Baseline, Excitation or Refractory) (Fig 2). Twelve compounds significantly affected the EPR in the Baseline phase (2 hyperactive and 10 hypoactive), including 1 aminated, 1 methylated, 2 nitrated, 4 hydroxylated, and 4 oxygenated PAHs. Twenty-five PAHs significantly changed EPR in the Excitation phase, including 2 aminated, 2 methylated, 3 heterocyclic, 3 nitrated, 5 oxygenated, and 9 hydroxylated PAHs. Of those, 6 were hyperactive and 19 were hypoactive. Hyperactive compounds were either heterocyclic, hydroxylated or nitrated. Only one compound (dibenzo[a,h]pyrene) significantly altered EPR in the Refractory period, and it had a hypoactive response in this period. This was also the only instance of a parent PAH causing a significant effect in the EPR.

Larval Photomotor Response (LPR)

A total of 97 PAHs induced a significant change in LPR in at least one phase (light or dark) (Fig 2). Fifty-four PAHs significantly changed LPR in the dark phase, including 1 aminated, 4 nitrated, 5 heterocyclic, 7 hydroxylated, 9 oxygenated, 10 methylated, and, 16 parent PAHs. Of those, 34 were hyperactive and 20 were hypoactive. The direction of the LPR effect tended to group based on structure and substitutions. Fourteen (87 %) parent compounds with an effect on the dark phase were hyperactive, as were 5 (71%) hydroxylated compounds, and 6 (60%) of methylated compounds. Two (50%) nitrated compounds that affected LPR caused hyperactivity in the dark. Heterocyclic and oxygenated compounds mostly caused hypoactivity, with 8 (66%) heterocyclic and oxygenated compounds that affected LPR causing hypoactivity.

Eighty-one PAHs significantly altered LPR in the light phase, including 1 aminated, 10 methylated, 10 oxygenated, 11 heterocyclic, 12 nitrated, 13 hydroxylated, and 24 parent PAHs. Of those, 47 were hyperactive and 34 were hypoactive. Similar patterns of direction of effect were seen in the light phase as in the dark phase. Sixteen (66%) parent, 9 (75%) nitrated, 6 (60%) oxygenated, and 8 (62%) of hydroxylated compounds with effects in the light phase caused hyperactivity. Meanwhile, 9 (82%) heterocyclic compounds and 5 (50%) methylated compounds caused hypoactivity in the light.

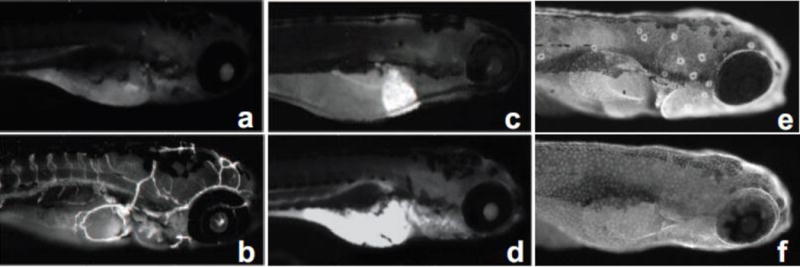

CYP1A Expression Patterns

The highest concentration tested that did not cause significant mortality for each PAH was assessed for CYP1A expression patterns with IHC (Table 1). Five different tissues expressed CYP1A following PAH exposure (Fig 3). Of the 123 PAHs tested, 66 induced CYP1A in at least one tissue type, with most limited to only one tissue (Fig 4a and b). The majority of the expression patterns were in the vasculature and the liver (Table 2). CYP1A was also expressed in the yolk, skin and neuromasts. Vasculature expression was the most common pattern, with 30 PAHs associated with expression of CYP1A in the vasculature. Additionally, 19 compounds induced observable liver expression, 18 induced skin expression, 16 induced yolk expression, and 7 induced neuromast expression. Neuromast expression was seen solely in conjunction with skin expression, and this was the second most common co-expression pattern observed. (Fig 4b). Skin expression was observed with PAHs of 5 or more rings, with the notable exceptions of the 4 ring nitrated derivatives 6-nitrochrysene and 1,6-dinitropyrene.

Figure 3.

Representative images illustrating CYP1A expression patterns (a) None (b) Vasculature (c) Liver (d) Yolk (e) Skin and Neuromasts (f) Skin

Figure 4.

(a) Proportion of PAHs with number of CYP1A expressing tissues. (b) Venn diagram of number of PAHs observed with specific tissue combinations expressing CYP1A.

Table 2.

Combinations of tissues expressing CYP1A observed for individual PAHs

| Tissue Type | Total | Compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Liver | 13 | 1,3-dihydroxynaphthalene; 1-hydroxyphenanthrene; 1-hydroxypyrene; 1,5-dimethylnaphthalene; 2,8-dinitrodibenzothiophene; 2-nitrodibenzothiophene; 2-nitrofluorene; 5-nitroacenaphthalene; 3-nitrophenanthrene; 9-nitrophenanthrene; Anthanthrene; Carbazole; Xanthone |

| Liver, Skin | 1 | Benzo[j]fluoranthene |

| Liver, Vasculature | 3 | 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene; 9-methylanthracene; 11H-benzo[b]fluoren-11-one |

| Liver, Yolk | 2 | 3-nitrobenzanthrone, 9-anthracene carbonitrile |

| Neuromast, Skin | 3 | Benzo[k]fluoranthene; Naphtho[2,3-e]pyrene; Naphtho[2,3-k]fluoranthene |

| Neuromast, Skin, Vasculature | 4 | Dibenz[a,h]anthracene; Dibenzo[a,h]pyrene; Dibenzo[a,i]pyrene; Dibenzo[b,k]fluoranthene; |

| Skin | 4 | 6-nitrochrysene; 7-nitrobenz[a]anthracene; Benzo[b]fluoranthene; Dibenz[a,c]anthracene |

| Skin, Vasculature | 5 | 1.6-dinitropyrene; 1-hydroxyindeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene; 3.7-dinitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene; 7-nitrobenzo[k]fluoranthene; Indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene |

| Skin, Yolk | 1 | Benzo[a]pyrene |

| Vasculature | 15 | 1,4-dimethylnaphthalene; 1,4-phenanthrenedione; 1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene; 2,3-dihydroxynaphthalene; 3-hydroxybenz[a]anthracene; 3-hydroxyfluorene; 5,12-naphthacenequinone; 6-methylchrysene; 10-hydroxybenzo[a]pyrene; Benzo[b]fluorine; Chrysene; Coronene; Dibenzofuran; Pyrene; Retene |

| Vasculature, Yolk | 3 | 1-aminopyrene; 1-hydroxynaphthalene; Fluoranthene |

| Yolk | 10 | 1,3-dinitropyrene; 1-nitropyrene; 2-ethylanthraquinone; 2-nitroanthracene; 2-nitrofluoranthene; 3-nitrofluoranthene; 8-methylquinoline; Acridine; Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene; Indole |

| N/A | 57 | 1,2-dimethylnaphthalene; 1,2-naphthoquinone; 1,4-anthraquinone; 1.6-dihydroxynaphthalene; 1,6-dimethylnaphthalene; 1,8-dimethylnaphthalene; 1,8-dinitropyrene; 1-methylnaphthalene; 1-nitronaphthalene; 2,3-dimethylanthracene; 2,6-dimethylnaphthalene; 2.7-dihydroxynaphthalene; 2-hydroxynaphthalene; 2-methylanthracene; 2-methylbenzofuran; 2-methylnaphthalene; 2-nitronaphthalene; 2-nitropyrene; 3-hydroxybenzo[e]pyrene; 3-hydroxyfluoranthene; 3-hydroxyphenanthrene; 3-nitrodibenzofuran; 4H-cyclopenta[def]phenanthren-4-one; 4H-cyclopenta[lmn]phenanthridine-5,9-dione; 4-hydroxychrysene; 4-hydroxyphenanthrene; 6h-benzo[c,d]pyren-6-one; 6-nitrobenzo[a]pyrene; 9,10-phenanthrenequinone; 9-aminophenanthrene; 9-anthracene carboxylic acid; 9-fluorenone; 9-hydroxyphenanthrene; 9-nitroanthracene; Acenaphthene; Acenaphthenequinone; Acenaphthylene; Anthracene; Anthraquinone; Benzanthrone; Benzo[c]phenanthrene[1,4]quinone; Benzo[e]pyrene; Benzo[g,h,i]perylene; Chromone; Dibenzo[j,l]fluoranthene; Fluorene; Naphthalene; Naphtho[1,2-b]fluoranthene; Naphtho[2,3-b]fluoranthene; Naphtho[2,3-j]fluoranthene; Perinaphthenone; Phenanthrene; Pyrene-4,5-dione; Quinoline; Thianaphthene; Triphenylene; Xanthene |

Selected Comparisons of PAH Subgroups

EPA RPF PAHs

Eighteen of the 27 RPF PAHs used by the USEPA were included in our developmental toxicity screen: anthracene, anthanthrene, benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[g,h,i]perylene, benzo[j]fluoranthene, benzo[k]fluoranthene, chrysene, dibenz[a,c]anthracene, dibenz[a,h]anthracene, dibenzo[a,h]pyrene, dibenzo[a,i]pyrene, dibenzo[a,l]pyrene, fluoranthene, indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene, naphtho[2,3-e]pyrene, phenanthrene, and pyrene. Anthracene and dibenzo[a,i]pyrene were the only compounds with no observed morphology effects. All other RPF PAHs fit into one of two categories: LPR effects only (Group 3), or modest non-mortality effects (Group 4). The most common affected endpoints were pericardial edema, caudal/pectoral fins and pigmentation. Fifteen (83%) the tested RPF PAHs were associated with observable CYP1A expression. Six PAHs expressed CYP1A in one tissue type, most commonly in the skin and vasculature (33% each), followed by liver or yolk expression (17% each). Six PAHs (33%) expressed CYP1A in two tissue types, most commonly in the skin (66%), followed by vasculature, neuromasts and liver (33% each). Three RPF PAHs (17%) expressed CYP1A in three tissues, vasculature, skin and neuromasts.

Naphthalene

Naphthalene bioactivity was limited to LPR hyperactivity in both the dark and light phases. The naphthalene derivatives tested included 1 oxygenated, 2 nitrated, 7 hydroxylated, and 8 methylated derivatives. All derivatives except 2,6-dimethylnaphthalene had LPR effects in at least one phase. 2,3-dihydroxynaphthalene was the only derivative with significant effects on EPR. Four derivatives had effects on mortality or morphology: 1,2-naphthoquinone, 1-hydroxynaphthalene, 2-hydroxynaphthalene and 1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene. The primary endpoint affected was 5 dpf mortality. The hydroxylated compounds had effects only at the highest concentrations tested, and caused yolk sac and pericardial edemas and pectoral fin malformations, while 1,2 naphthoquinone caused mortality at some of the lowest concentrations tested. Although the majority of naphthalene derivatives did not express CYP1A, some additions of methyl or hydroxyl functional groups resulted in CYP1A expression. 1-hydroxynaphthalene induced vasculature CYP1A expression, but not 2-hydroxynaphthalene. Both dihydroxynaphthalenes with a hydroxyl group in position 3 induced CYP1A expression, but the position of the second hydroxyl group determined the tissue (vasculature for 2,3, liver for 1,3). 1,5-dihydroxynaphthalene also resulted in vasculature instead of liver expression. Similar patterns existed for 1,5-dimethylnaphthalene (liver), while methyl groups at the 1,4 positions resulted in vasculature expression.

Anthracene

Anthracene and several derivatives, including a carboxylated derivative, a carbonitrile derivative, 3 quinones, 2 nitrated and 3 methylated derivatives were tested. Anthracene was not bioactive in any of the developmental toxicity assays and not associated with expression of CYP1A, however all the tested derivatives were bioactive in at least one developmental toxicity assay. The primary effect of anthracene derivatives was on LPR behavior; every derivative except 2-nitroanthracene and 2-ethylanthraquinone affected LPR behavior. The majority of anthracene derivatives did not induce tissue expression of CYP1A. Anthraquinone did not cause morphological effects, but the addition of an ethyl group in the 2 position resulted in effects across 15 endpoints, including increased mortality, and yolk expression of CYP1A. 1,4-anthraquinone was the most toxic derivative tested, with increased mortality at concentrations below 10 μM. While inactive in all developmental toxicity assays, 2-nitroanthracene did induce CYP1A expression in the yolk. 9-anthracene carboxylic acid did not induce CYP1A tissue expression, but 9-anthracene carbonitrile was associated with expression in both liver and yolk. Methylation generally did not affect CYP1A expression, but 9-methylanthracene was associated with CYP1A expression in both vasculature and liver.

Phenanthrene

Phenanthrene did not induce mortality or morphology changes, EPR effects, or CYP1A tissue expression at the concentrations tested, but did induce hyperactivity in the light period of LPR. One aminated, 1 methylated, 2 oxygenated, 2 nitrated, and 4 hydroxylated phenanthrenes were screened. Addition of functional groups to phenanthrene resulted in increased bioactivity, except for 3-nitrophenanthrene, which had the same toxicity profile as the parent compound. The developmental effects of the derivatives were primarily characterized by 120 hpf mortality, craniofacial malformations, and yolk sac and pericardial edema. The majority of derivatives did not induce CYP1A expression, however 4 phenanthrene derivatives had liver expression, the most common CYP1A pattern amongst the phenanthrenes. In addition to effects on LPR in the light, 3,6-dimethylphenanthrene caused hypoactivity in the EPR, and induced CYP1A expression in the vasculature and the liver.

Pyrene

Unsubstituted pyrene had high LELs (low bioactivity) for several endpoints, vasculature expression of CYP1A, and significant LPR effects. One aminated, one oxygenated, one hydroxylated and 5 nitrated derivatives were screened. The mononitrated derivatives had decreased LELs compared to pyrene, but they affected only the cumulative ‘any’ endpoints (2-nitropyrene), or the LPR (1-nitropyrene). Compared to unsubstituted pyrene, exposure to pyrene-4,5-dione, 1,6-dinitropyrene, 1,3-dinitropyrene and 1-aminopyrene dramatically increased the developmental toxicity across multiple endpoints, with significant yolk sac and pericardial edemas, and craniofacial, axial, and fin malformations at lower concentrations. 1-hydroxypyrene and 1,8-dinitropyrene had very similar patterns of effects to pyrene, but those effects were significant at much lower concentrations. Pyrene substitutions altered CYP1A expression patterns, but with no clear trend towards a specific tissue type. In addition to vasculature expression, 1-aminopyrene elicited yolk expression and 1,6-dinitropyrene elicited skin CYP1A expression. 2-nitropyrene, 1,8-dinitropyrene, and pyrene-4,5-dione were not associated with CYP1A expression, but 1-nitropyrene and 1,3-dinitropyrene both elicited yolk expression. 1-hydroxypyrene was the only pyrene derivative associated with liver expression.

Discussion

In the environment, human and animal exposure to PAHs occurs as complex mixtures of parent and substituted structures. A lack of developmental toxicity data for environmentally relevant, substituted PAHs has hindered the estimation of the hazard potential of environmental mixtures (Andersson and Achten 2015). Our results establish a baseline of vertebrate developmental effects associated with exposure to a highly diverse library of 123, mostly substituted, PAHs. We demonstrated that the relationship between structure and toxicity was complex and not predictable by generalized descriptors of physical properties.

No two individual PAH developmental response profiles tested here were identical, and each substituted class ranged from no detectable adverse effects to severely toxic across multiple endpoints. The developmental toxicity of a substituted PAH structure was not predicted by number of rings, parent compound bioactivity, or log Kow (Figure S1). Furthermore, the bioactivity of 18 of the US EPA’s 27 priority PAHs grossly under-represented the range of toxic effects that we observed in the 123 PAH library, emphasizing the shortcomings of focusing on benzo[a]pyrene and parent PAHs for regulatory purposes. We note that others have recently highlighted similar toxicological limitations with the USEPA standardized PAH lists (Andersson and Achten 2015; Andreasen 2002).

Several morphological endpoints, namely pericardial edema, yolk sac edema, and craniofacial malformations, were common among a majority of the PAHs with developmental effects. This is in accord with vertebrate developmental malformations in response to other strong AhR ligands, the cardiovascular effects of PAHs (Incardona et al. 2004; Incardona et al. 2006; Incardona et al. 2011; Knecht et al. 2013) and their AhR2-dependent toxicity patterns, including dioxin-like toxicity and CYP1A expression patterns (Goodale et al. 2012; Knecht et al. 2013). However, effects not previously associated with developmental PAH exposure were also frequent, including caudal fin, pectoral fin, pigmentation, and touch response abnormalities, demonstrating that solely focusing on cardiovascular effects would ignore other important readouts of hazard potential.

CYP1A expression in the larval zebrafish vasculature and liver is a recognized reporter of AhR2 and AhR1A activation respectively (Goodale et al. 2012). Expression of CYP1A in the skin at 120 hpf was previously observed only in response to nitrated PAHs (Chlebowski et al. 2017), though skin expression of CYP1A has been observed earlier in development in response to other AhR2 ligands (Kim et al. 2013). In this study, skin expression of CYP1A was only associated with high molecular weight (> MW 250), low solubility (−8.8 < log S < −6.7) PAHs. A possible explanation for this pattern of CYP1A expression is limited bioavailability, restricting metabolism to the surface of the fish. As a next step, this hypothesis should be tested by examining the relative potency factor of these high MW, low solubility PAHs, measured as transactivation of an AhR2-luciferase reporter (Larsson et al. 2014; Larsson et al. 2012).

Neuromasts are sensory organs in fish and an important part of the lateral line and otic sensory system. These components are analagous to the mammalian inner ear (Ton and Parng 2005). They are not typically associated with expression of the CYP450 gene family, however, otic expression of CYP1A is known (Incardona et al. 2005). The ten compounds associated with neuromast CYP1A expression also had altered larval photomotor responses (LPRs). This may be indirect evidence of disrupted lateral line development, previously associated with abnormal larval photomotor and startle response behaviors (de Esch et al. 2012).

While yolk syncytial layer expression of CYP1A has been previously observed in zebrafish embryos exposed to PAHs (Chlebowski et al. 2017; Goodale et al. 2015), little is known about its cause or relevance. CYP450 expression was noted in the yolk syncytial layer in connection with steroidogenesis earlier in development (Hsu et al. 2002), suggesting that PAH-elicited CYP1A expression is connected to steroid metabolism in the yolk.

An abnormal embryonic photomotor response (EPR) at 24 hpf is generally highly predictive of adverse effects at 120 hpf for a variety of chemical classes (Reif et al. 2016). Unexpectedly, of the 123 PAHs tested here, only 28 resulted in an abnormal EPR. Of the compounds with significant EPR effects, 68% had morphological effects at 24 hpf, and 75% resulted in morphological effects at 120 hpf, i.e., PAHs with EPR effects comprised only 36% of the structures that elicited morphological effects by 120 hpf. This, combined with the fact that only 28% of the PAHs had morphological effects at 24 hours, suggested that the developmental window of bioactivity for most PAHs began after 24 hpf. EPR effects were less likely for PAHs associated with CYP1A expression at 120 hpf (14%) than without (26%). This is consistent with the onset of functional phase I and II metabolism in the developing zebrafish, and conversion of some PAHs to toxic metabolites (Elie et al. 2015; Goldstone et al. 2010; van Grevenynghe et al. 2004).

The LPR assay revealed bioactivity for several PAHs that did not affect other endpoints, highlighting the value of behavioral endpoints in chemical toxicity assessments. Of the 56 PAHs with significant LPR effects, 16 (29%) had no bioactivity in any other assay. The compounds in this group spanned the entirety of the PAH library, and did not have any obvious structural commonalities. LPR effects were equally likely for PAHs with CYP1A expression at 120 hpf (45%) than PAHs without CYP1A expression (47%). Previous work with environmental mixtures was concordant with the hypoactivity observed here, mostly associated with exposure to substituted PAHs (Perrichon et al. 2016).

The EPR and LPR outcomes suggest that a diverse range of PAH structures can elicit neurobehavioral effects. A higher incidence of LPR effects than EPR effects, and indirect evidence of a post 24 hpf window of bioactivity for most PAHs, indicates that the EPR will likely not be a good predictor of PAH mixture toxicity in future work. Eleven PAHs were not associated with behavioral or morphological effects. This may have resulted from solubility limits in the aqueous exposure medium, where the threshold for morphological or behavioral effects is higher than the top concentrations tested. This might also have been the case for the five dissimilar compounds with no morphological or behavioral effects, but observable CYP1A expression. The CYP1A induction suggests that the compounds interacted with phase I metabolism, while lack of toxicological responses suggests that the five were successfully detoxified or below a concentration threshold for overt toxicity. The remaining six compounds with no associated adverse effects might similarly have been below the toxic threshold. The exceedingly low aqueous solubility of these compounds means that a static bath exposure will likely be unsuccessful for evaluating a toxic threshold and that a direct injection approach should be adopted.

Body burden studies were not performed in parallel with the 123 different exposure experiments and therefore the degree to which uptake influenced our results is unknown. There is additional uncertainty in the actual tested concentration, because sorptive losses of up to 50% of the analyte have been observed for PAHs in contact with polystyrene (Chlebowski et al. 2016). These uncertainties complicate the modeling of PAH toxicity by log Kow, especially because experimental values of log Kow do not exist for most PAHs. Dosimetry modeling is a clear future research need.

Current and proposed methods of modeling PAH toxicity and regulating PAHs in the environment are increasingly recognized as inadequate and overly focused on parent compounds (Andersson and Achten 2015). Benzo[a]pyrene has been used as a reference for toxicity estimates in many regulatory settings (USEPA 2010). However, in our assays, benzo[a]pyrene was only somewhat representative of the toxicity of other parent compounds, and was far less bioactive than most of the oxygenated and nitrated substitutes. The carcinogenicity and mutagenicity of alkylated, oxygenated and nitrated PAHs can often equal that of the 27 EPA RPF PAHs, and there is ongoing concern that ignoring these derivatives obscure the majors drivers of toxicity in environmental risk assessment (Andersson and Achten 2015). Our data similarly suggested that substituted PAHs are often much more developmentally toxic than their parent compounds.

Although log Kow is generally predictive of bioavailability, it was clearly not predictive of developmental hazard potential for the 123 PAHs here (Figure S1). While general physical descriptors like log Kow are easy to employ and thus highly tempting to resort to as a means to predict the hazard potential and fate of contamination scenarios, results like ours demonstrate that a whole animal biosensor approach is both rapid and far more informative.

In conclusion, we characterized the toxicity of 123 parent, oxygenated, hydroxylated, and nitrated PAHs, and identified putative differential AhR dependencies among them. The developmental zebrafish platform enabled a rapid but comprehensive evaluation of the hazard potential of these diverse structures at low cost relative to mammalian models. The results of our somewhat unconventional focus on mostly substituted PAHs, rather than parent USEPA standards, highlight a clear potential for more accurate assessments of environmental and human health hazard. The traditional view of PAHs presenting inherently uniform toxicity, i.e., in the vicinity of B[a]P bioactivity, has already shifted to more refined structure-activity based assessments, and the much needed inclusion of substituted PAH species is well underway. Future studies incorporating a comprehensive approach to body burden will further refine the mechanisms driving the differential toxic effects of individual and mixtures of PAHs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank members of the Tanguay Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory for assistance with fish husbandry and screening. This work was supported by NIEHS grants P42 ES016465, ES007060, and P30 ES000210.

References

- Andersson JT, Achten C. Time to Say Goodbye to the 16 EPA PAHs? Toward an Up-to-Date Use of PACs for Environmental Purposes. Polycycl Aromat Compd. 2015;35(2–4):330–354. doi: 10.1080/10406638.2014.991042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen EA. Tissue-Specific Expression of AHR2, ARNT2, and CYP1A in Zebrafish Embryos and Larvae: Effects of Developmental Stage and 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin Exposure. Toxicological Sciences. 2002;68(2):403–419. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.2.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal V, Kim KH. Review of PAH contamination in food products and their health hazards. Environ Int. 2015;84:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearr JS, Stapleton HM, Mitchelmore CL. Accumulation and DNA damage in fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas) exposed to 2 brominated flame-retardant mixtures, Firemaster 550 and Firemaster BZ-54. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2010;29(3):722–9. doi: 10.1002/etc.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiard SM, Meyer JN, Wassenberg DM, Hodson PV, Di Giulio RT. Nonadditive effects of PAHs on Early Vertebrate Development: mechanisms and implications for risk assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2008;105(1):5–23. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese BL, Ozretich RJ, Lamberson JO, et al. Toxicity and Phototoxicity of Mixtures of Highly Lipophilic PAH Compounds in Marine Sediment: Can the PAH Model Be Extrapolated? Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 1999;36:270–280. doi: 10.1007/s002449900471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd WA, Smith MV, Co CA, et al. Developmental Effects of the ToxCast Phase I and Phase II Chemicals in Caenorhabditis elegans and Corresponding Responses in Zebrafish, Rats, and Rabbits. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124(5):586–93. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1409645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burczynski M, Lin H, Penning T. Isoform-specific Induction of a Human Aldo-Keto Reductase by Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs), Electrophiles, and Oxidative Stress: Implications for the Alternative Pathway of PAH Activation Catalyzed by Human Dihydrodiol Dehydrogenase. Cancer Research. 1999;59(3):8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Tang Y, Jiang X, et al. Early postnatal benzo(a)pyrene exposure in Sprague-Dawley rats causes persistent neurobehavioral impairments that emerge postnatally and continue into adolescence and adulthood. Toxicol Sci. 2012;125(1):248–61. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowski AC, Garcia GR, La Du JK, et al. Mechanistic investigations into the developmental toxicity of nitrated and heterocyclic PAHs. Toxicol Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlebowski AC, Tanguay RL, Simonich SL. Quantitation and prediction of sorptive losses during toxicity testing of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) and nitrated PAH (NPAH) using polystyrene 96-well plates. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2016;57:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran RE, Jeong H, Haddadi S, et al. Identification of products formed during the heterogeneous nitration and ozonation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Atmospheric Environment. 2016;128:92–103. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2015.12.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crepeaux G, Bouillaud-Kremarik P, Sikhayeva N, Rychen G, Soulimani R, Schroeder H. Late effects of a perinatal exposure to a 16 PAH mixture: Increase of anxiety-related behaviours and decrease of regional brain metabolism in adult male rats. Toxicol Lett. 2012;211(2):105–13. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepeaux G, Bouillaud-Kremarik P, Sikhayeva N, Rychen G, Soulimani R, Schroeder H. Exclusive prenatal exposure to a 16 PAH mixture does not impact anxiety-related behaviours and regional brain metabolism in adult male rats: a role for the period of exposure in the modulation of PAH neurotoxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2013;221(1):40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Esch C, Slieker R, Wolterbeek A, Woutersen R, de Groot D. Zebrafish as potential model for developmental neurotoxicity testing: a mini review. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2012;34(6):545–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, et al. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2009;30(4):293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K, Zon LI. Zebrafish: a model system for the study of human disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2000;10(3):252–6. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elie MR, Choi J, Nkrumah-Elie YM, Gonnerman GD, Stevens JF, Tanguay RL. Metabolomic analysis to define and compare the effects of PAHs and oxygenated PAHs in developing zebrafish. Environ Res. 2015;140:502–10. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R, Enewold L, Pellizzari E, et al. Smoking Increases Carcinogenic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Human Lung Tissue. Cancer Research. 2001;61(17):6367–6371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstone J, McArthur A, Kubota A, et al. Identification and developmental expression of the full complement of Cytochrome P450 genes in Zebrafish. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1):643. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale BC, La Du J, Tilton SC, et al. Ligand-Specific Transcriptional Mechanisms Underlie Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor-Mediated Developmental Toxicity of Oxygenated PAHs. Toxicol Sci. 2015;147(2):397–411. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale BC, La Du JK, Bisson WH, Janszen DB, Waters KM, Tanguay RL. AHR2 mutant reveals functional diversity of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in zebrafish. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29346. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu H-J, Hsiao P, Kuo M-W, Chung B-C. Expression of zebrafish cyp11a1 as a maternal transcript and in yolk syncytial layer. Gene Expression Patterns. 2002;2(3–4):219–222. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Carls MG, Teraoka H, Sloan CA, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-independent toxicity of weathered crude oil during fish development. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(12):1755–62. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Defects in cardiac function precede morphological abnormalities in fish embryos exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;196(2):191–205. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Day HL, Collier TK, Scholz NL. Developmental toxicity of 4-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in zebrafish is differentially dependent on AH receptor isoforms and hepatic cytochrome P4501A metabolism. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;217(3):308–21. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incardona JP, Linbo TL, Scholz NL. Cardiac toxicity of 5-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is differentially dependent on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor 2 isoform during zebrafish development. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;257(2):242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jariyasopit N, McIntosh M, Zimmermann K, et al. Novel nitro-PAH formation from heterogeneous reactions of PAHs with NO2, NO3/N2O5, and OH radicals: prediction, laboratory studies, and mutagenicity. Environ Sci Technol. 2014a;48(1):412–9. doi: 10.1021/es4043808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jariyasopit N, Zimmermann K, Schrlau J, et al. Heterogeneous reactions of particulate matter-bound PAHs and NPAHs with NO3/N2O5, OH radicals, and O3 under simulated long-range atmospheric transport conditions: reactivity and mutagenicity. Environ Sci Technol. 2014b;48(17):10155–64. doi: 10.1021/es5015407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Park HJ, Kim JH, et al. Cyp1a reporter zebrafish reveals target tissues for dioxin. Aquat Toxicol. 2013;134–135:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203(3):253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AL, Goodale BC, Truong L, et al. Comparative developmental toxicity of environmentally relevant oxygenated PAHs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;271(2):266–75. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AL, Truong L, Simonich MT, Tanguay RL. Developmental benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) exposure impacts larval behavior and impairs adult learning in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017;59:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurogi K, Liu TA, Sakakibara Y, Suiko M, Liu MC. The use of zebrafish as a model system for investigating the role of the SULTs in the metabolism of endogenous compounds and xenobiotics. Drug Metab Rev. 2013;45(4):431–40. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2013.835629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Hagberg J, Giesy JP, Engwall M. Time-dependent relative potency factors for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their derivatives in the H4IIE-luc bioassay. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;33(4):943–53. doi: 10.1002/etc.2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson M, Orbe D, Engwall M. Exposure time-dependent effects on the relative potencies and additivity of PAHs in the Ah receptor-based H4IIE-luc bioassay. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2012;31(5):1149–57. doi: 10.1002/etc.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Fol V, Brion F, Hillenweck A, et al. Comparison of the In Vivo Biotransformation of Two Emerging Estrogenic Contaminants, BP2 and BPS, in Zebrafish Embryos and Adults. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(4) doi: 10.3390/ijms18040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-T, Lin Y-C, Lee W-J, Tsai P-J. Emission of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Their Carcinogenic Potencies from Cooking Sources to the Urban Atmosphere. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002;111(4):483–487. doi: 10.1289/ehp.5518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Weisman D, YE Y-B, et al. An oxidative stress response to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure is rapid and complex in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Science. 2009;176(3):375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luderer U, Christensen F, Johnson WO, et al. Associations between urinary biomarkers of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and reproductive function during menstrual cycles in women. Environ Int. 2017;100:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundstedt S, White PA, Lemieux CL, et al. Sources, Fate, and Toxic Hazards of Oxygenated Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) at PAH-contaminated Sites. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 2007;36(6):475–85. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[475:sfatho]2.0.co;2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447(2007)36[475:SFATHO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrell D, Truong L, Jephson C, et al. Automated zebrafish chorion removal and single embryo placement: optimizing throughput of zebrafish developmental toxicity screens. J Lab Autom. 2012;17(1):66–74. doi: 10.1177/2211068211432197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew LK, Andreasen EA, Tanguay RL. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation inhibits regenerative growth. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69(1):257–65. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.018044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew R, McGrath JA, Di Toro DM. Modeling polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon bioaccumulation and metabolism in time-variable early life-stage exposures. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 2008;27(7):1515–1525. doi: 10.1897/07-355.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes PD, Haggard DE, Gonnerman GD, Tanguay RL. Advanced morphological-behavioral test platform reveals neurodevelopmental defects in embryonic zebrafish exposed to comprehensive suite of halogenated and organophosphate flame retardants. Toxicological Sciences. 2015;145(1) doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski SR, Wilbur S, Chou CH, et al. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s 1997 priority list of hazardous substances. Latent effects–carcinogenesis, neurotoxicology, and developmental deficits in humans and animals. Toxicol Ind Health. 1999;15(7):602–44. doi: 10.1177/074823379901500702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peal DS, Peterson RT, Milan D. Small molecule screening in zebrafish. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3(5):454–60. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9212-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Chang HW, Tang D, et al. Early-life exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and ADHD behavior problems. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Li Z, Whyatt R, et al. Prenatal airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure and child IQ at age 5 years. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):e195–202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Rauh V, Whyatt RM, et al. Effect of Prenatal Exposure to Airborne Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Neurodevelopment in the First 3 Years of Life among Inner-City Children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2006;114(8):1287–1292. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Tang D, Tu Y-H, et al. Biomarkers in Maternal and Newborn Blood Indicate Heightened Fetal Susceptibility to Procarcinogenic DNA Damage. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2004;112(10):1133–1136. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera FP, Whyatt RM, Jedrychowski W, et al. Recent Developments in Molecular Epidemiology: A Study of the Effects of Environmental Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons on Birth Outcomes in Poland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1998;147(3):309–314. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrichon P, Le Menach K, Akcha F, Cachot J, Budzinski H, Bustamante P. Toxicity assessment of water-accommodated fractions from two different oils using a zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryo-larval bioassay with a multilevel approach. Sci Total Environ. 2016;568:952–66. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.04.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulster EL, Main K, Wetzel D, Murawski S. Species-Specific Metabolism of Naphthalene and Phenanthrene in Three Species of Marine Teleosts Exposed to Deepwater Horizon Crude Oil. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1002/etc.3898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos KS, Moorthy B. Bioactivation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon carcinogens within the vascular wall: implications for human atherogenesis. Drug Metab Rev. 2005;37(4):595–610. doi: 10.1080/03602530500251253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindra K, Sokhi R, Vangrieken R. Atmospheric polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Source attribution, emission factors and regulation. Atmospheric Environment. 2008;42(13):2895–2921. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reif DM, Truong L, Mandrell D, Marvel S, Zhang G, Tanguay RL. High-throughput characterization of chemical-associated embryonic behavioral changes predicts teratogenic outcomes. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(6):1459–70. doi: 10.1007/s00204-015-1554-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgman A, Smith CJ, Perfetti TA. The composition of cigarette smoke: a retrospective, with emphasis on polycyclic components. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19(10):573–95. doi: 10.1191/096032700701546514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundle A, Hoepner L, Hassoun A, et al. Association of childhood obesity with maternal exposure to ambient air polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175(11):1163–72. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabljic A. QSAR models for estimating properties of persistent organic pollutants required in evaluation of their environmental fate and risk. Chemosphere. 2001;43:363–375. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(00)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott JA, Incardona JP, Pelkki K, Shepardson S, Hodson PV. AhR2-mediated, CYP1A-independent cardiovascular toxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos exposed to retene. Aquat Toxicol. 2011;101(1):165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shailaja MS, Rajamanickam R, Wahidulla S. Formation of genotoxic nitro-PAH compounds in fish exposed to ambient nitrite and PAH. Toxicol Sci. 2006;91(2):440–7. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoneit BR, Bi X, Oros DR, Medeiros PM, Sheng G, Fu J. Phenols and hydroxy-PAHs (arylphenols) as tracers for coal smoke particulate matter: source tests and ambient aerosol assessments. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41(21):7294–302. doi: 10.1021/es071072u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team RC, editor. Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ton C, Parng C. The use of zebrafish for assessing ototoxic and otoprotective agents. Hear Res. 2005;208(1–2):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L, Bugel SM, Chlebowski A, et al. Optimizing multi-dimensional high throughput screening using zebrafish. Reprod Toxicol. 2016;65:139–147. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (IRIS) IRIS, editor. USEPA. Development of a Relative Potency Factor (RPF) Approach for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon (PAH) Mixtures. Washington, D.C: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- van Grevenynghe J, Sparfel L, Le Vee M, et al. Cytochrome P450-dependent toxicity of environmental polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons towards human macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317(3):708–16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignet C, Devier MH, Le Menach K, et al. Long-term disruption of growth, reproduction, and behavior after embryonic exposure of zebrafish to PAH-spiked sediment. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014a;21(24):13877–87. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignet C, Le Menach K, Lyphout L, et al. Chronic dietary exposure to pyrolytic and petrogenic mixtures of PAHs causes physiological disruption in zebrafish–part II: behavior. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2014b;21(24):13818–32. doi: 10.1007/s11356-014-2762-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz DC, Hipszer RA, Leet JK, Raftery TD. Leveraging Embryonic Zebrafish To Prioritize ToxCast Testing. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 2015;2(7):171–176. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.5b00123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Meng L, Pittman EN, et al. Quantification of urinary mono-hydroxylated metabolites of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by on-line solid phase extraction-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2017;409(4):931–937. doi: 10.1007/s00216-016-9933-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Warshawsky D. Metabolic activation of polycyclic and heterocyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and DNA damage: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;206(1):73–93. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Li X, Jing Y, et al. Transplacental transfer of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in paired samples of maternal serum, umbilical cord serum, and placenta in Shanghai, China. Environ Pollut. 2017;222:267–275. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Tao S. Global atmospheric emission inventory of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) for 2004. Atmospheric Environment. 2009;43(4):812–819. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.10.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.