Abstract

BACKGROUND

Most clinical opioids act through mu opioid receptors. They effectively relieve pain, but are limited by side-effects, such as constipation, respiratory depression, dependence and addiction. Many efforts have been made towards developing potent analgesics lacking side effects. 3-iodobenzoyl-6β-naltrexamide (IBNtxA) is a novel class of opioid active against thermal, inflammatory and neuropathic pain, without respiratory depression, physical dependence and reward behavior. The mu opioid receptor (OPRM1) gene undergoes extensive alternative pre-mRNA splicing, generating multiple splice variants that are conserved from rodents to humans. One type of the variants is the exon 11 (E11)-associated truncated variant containing 6 transmembrane domains (6TM variant). There are five 6TM variants in the mouse Oprm1 gene, including mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N, mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L. Gene targeting mouse models selectively removing 6TM variants in E11 knockout (KO) mice eliminated IBNtxA analgesia without affecting morphine analgesia. Conversely, morphine analgesia is lost in an exon 1 (E1) KO mouse that lacks all 7TM variants but retains 6TM variant expression, while IBNtxA analgesia remains intact. Elimination of both E1 and E11 in an E1/E11 double KO abolishes both morphine and IBNtxA analgesia. Reconstituting expression of the 6TM variant mMOR-1G in E1/E11 KO mice through lentiviral expression rescued IBNtxA, but not morphine, analgesia. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of lentiviral expression of the other 6TM variants in E1/E11 KO mice on IBNtxA analgesia.

METHODS

Lentiviruses expressing 6TM variants were packaged in HEK293T cells, concentrated by ultracentifigation and intrathecally administrated for three times. Opioid analgesia was determined using a radiant-heat tail-flick assay. Expression of lentiviral 6TM variant mRNAs was examined by PCR or qPCR.

RESULTS

All the 6TM variants restored IBNtxA analgesia in E1/E11 KO mouse, while morphine remained inactive. Expression of lentiviral 6TM variants was confirmed by PCR or qPCR. IBNtxA ED50 values determined from cumulative dose-response studies in the rescued mice were indistinguishable from wild-type animals. IBNtxA analgesia was maintained for up to 33 weeks in the rescue mice and was readily antagonized by the opioid antagonist levallorphan.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrated the pharmacological relevance of mouse 6TM variants in IBNtxA analgesia and established that a common functional core of the receptors corresponding to the transmembrane domains encoded by exons 2 and 3 is sufficient for activity. Thus, 6TM variants offer potential therapeutic targets for a distinct class of analgesics that are effective against broad-spectrum pain models without many side-effects associated with traditional opioids.

Introduction

The use of mu opioids to relieve pain is often limited by side-effects, such as constipation, respiratory repression, itch, physical dependence and addiction. Recently, a novel class of opioids acting through exon 11 associated 6 transmembrane (TM) variants of the mu opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) has been developed that has an advantageous side-effect profile, exemplified by IBNtxA (3-iodobenzoyl-6β-naltrexamide).(1,2) IBNtxA is 10-fold more potent than morphine in thermal assays and even more effective in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models.(3) Unlike traditional opioids, IBNtxA does not produce respiratory depression, physical dependence or reward behavior in a conditioned place preference assay and shows no cross tolerance to morphine.(1–3) Although IBNtxA analgesia is mediated through the mu opioiod receptor gene Oprm1, it acts through a target that is genetically distinct from morphine.

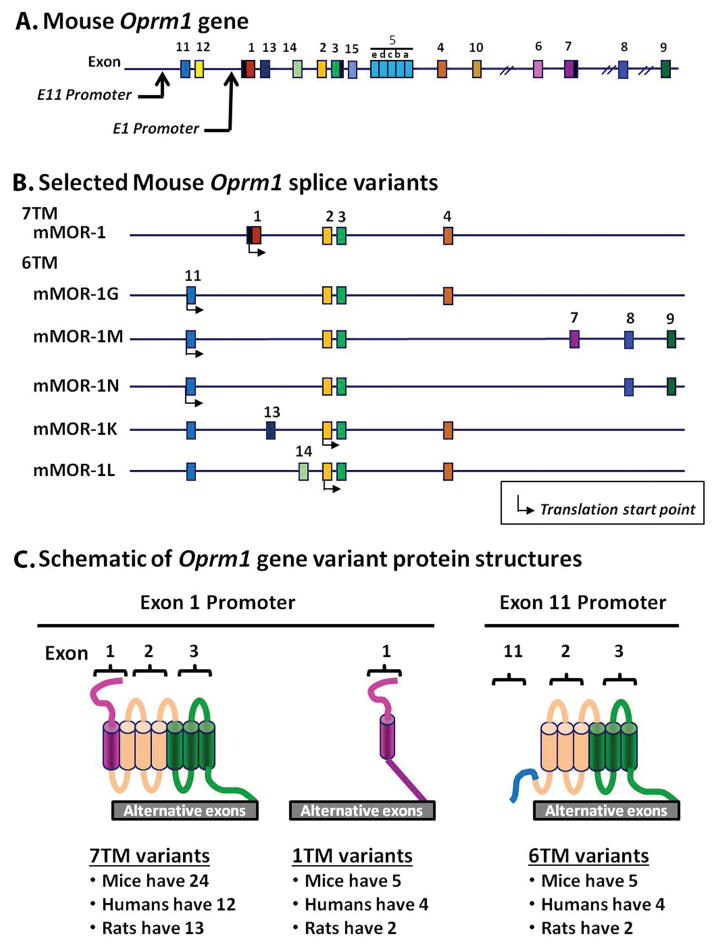

The single-copy mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm1) undergoes extensive alternative pre-mRNA splicing, generating multiple splice variants with a pattern that is conserved from rodents to humans.(4) These splice variants fall into three structurally distinct categories (Fig. 1). The exon 1 (E1)-associated full-length 7 transmembrane (7TM) proteins are most abundant. They are identical except for the sequences at the tip of the intracellular C-terminus. The second set, the E1-associated truncated 1TM variants, possess only the N-terminus and first TM present in the full-length 7TM receptors with alternative C-termini. The third class are the exon 11 (E11)-associated truncated 6TM variants. These lack the first TM present in the full length 7TM receptors. The functional relevance of the 7TM splice variants was based upon their unique region- and/or cell-specific expression, mu agonist-induced G protein coupling, phosphorylation, internalization and post-endocytic sorting, and their involvement in vivo morphine activity.(1,3–17) The truncated 1TM variants do not bind ligand, but function as molecular chaperones that facilitate expression of the 7TM mu receptor and thereby enhance morphine analgesia.(18)

Figure 1. Schematic of the mouse Oprm1 gene, selected splice variants and predicted variant protein structures.

A. The mouse mu opioid receptor gene (Oprm1) structure. Exons and introns are shown by color-coded boxes and black horizontal lines, respectively. Exons are numbered based upon their discovery. Promoters are indicated by black arrows.

B. Alternative splicing and exon composition of selected mouse Oprm1 gene splice variants. The initial 7TM mMOR-1 and the five murine 6TM variants are shown. Translation start points are shown by black arrow under the exons.

C. Schematic of Oprm1 gene variant protein structures. The Oprm1 gene undergoes extensive alternative pre-mRNA splicing, generating three classes of structurally distinct variants: C-terminal full-length 7TM variants, truncated 1TM variants and 6TM variants. These variants are conserved from rodent to humans (see review (4) for complete list including exon composition and sequences). The N-terminus, intracellular and extracellular loops are indicated by color-coded lines, and transmembrane domains are shown by color-coded cylinders. Each color presents the coding region predicted from an exon. Note: Since the translation start point of mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L is in exon 2, these variants will not contain the amino acid sequences associated with exon 11 (blue line).

Oprm1 gene targeting mouse models provide useful tools to decipher the function of truncated 6 transmembrane (6TM) splice variants (Table 1). IBNtxA analgesia was completely abolished in E11 KO mice lacking all the truncated 6TM variants while still expressing the 7TM C-terminal variants, despite the fact that morphine analgesia remained intact.(1,4,19) Conversely, the selective loss of all the 7TM variants in an E1 KO mouse that still expressed the 6TM variants (20) eliminated morphine analgesia, but not IBNtxA analgesia.(1,4) This residual analgesia did not involve delta or kappa receptors since IBNtxA showed full analgesic activity in a triple KO mouse lacking delta, kappa and E1-associated 7TM and 1TM receptors.(1) Together, these studies suggest that E11-associated 6TM variants mediate IBNtxA analgesia while E1-associated 7TM variants are responsible for morphine analgesia. A gain of function study further established the role of a 6TM variant, mMOR-1G, in IBNtxA analgesia.(16,21) In a complete mu opioid receptor (Oprm1) knockout mouse in which both exons 1 and 11 (E1/E11 KO) were targeted, eliminating expressions of all Oprm1 variants, both morphine and IBNtxA were inactive. Expressing mMOR-1G through lentiviral-mediated delivery in the E1/E11 KO mice rescued IBNtxA, but not morphine, analgesia, suggesting that mMOR-1G is both necessary and sufficient for IBNtxA analgesia.

Table 1.

Oprm1 knockout (KO) mouse models and opioid analgesia

| Knockout (KO) mouse model | Variant | Analgesia | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| 7TM | 1TM | 6TM | Morphine | IBNtxA | |

|

|

|

|

|||

| E1-KOa | Lost | Lost | Retained | Lost | Retained |

|

|

|

|

|||

| E11-KOb | Retained | Retained | Lost | Retained | Lost |

|

|

|

|

|||

| E1/E11-KOc | Lost | Lost | Lost | Lost | Lost |

Reference (20);

Reference (16)

The E1-KO (exon 1 knockout) mice lack all the 7TM (transmembrane) and 1TM variants because of loss of exon 1, but still express 6TM variants. On the other hand, the E11-KO (exon 11 knockout) mice lack all the 6TM variants because of loss of exon 11, but still express 7TM and 1TM variants. The E1/E11-KO (exons 1 & 11 knockout) mice lack all the variants because of loss of both exons 1 and 11. Morphine analgesia was lost in E1-KO and E1/E11-KO mice, but retained in E11-KO mice. In contrast, IBNtxA analgesia was lost in E11-KO and E1/E11-KO, but retained in E1-KO mice. These results suggest that morphine analgesia depends on 7TM variants, and IBNtxA analgesia is mediated through 6TM variants.

Mice express five E11-associated 6TM variants: mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N, mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L, with mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L producing identical proteins. Their structures encompassing the transmembrane domains and loops that are encoded by exons 2 and 3, are identical, but their C-terminal sequences vary and mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L lack the N-terminal amino acid sequence encoded by exon 11. The current study examines whether the rescue of IBNtxA analgesia was selective for mMOR-1G or could be extended to the other 6TM variants. Understanding the structural requirements for 6TM activity would be helpful in the development of novel, safer analgesic drugs.

Methods

Animals

The E1/E11 knockout (KO) mouse in a mixture of 129S6/SvEvTac (Taconic)/C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratory) background was generated as described previously (16). Adult (8 – 16 weeks-old) wildtype (WT) and homozygous (KO) male mice were used. All mice were housed in groups of five, maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle and given ad libitum access to food and water. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. All animal studies were performed in our standard behavioral procedure room between 9:00am and 5:00pm.

Drugs

Morphine sulfate was obtained from the Research Technology Branch of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Rockville, MD). Levallorphan was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (L121), and IBNtxA (3-iodobenzoyl-6β-naltrexamine) was synthesized and the structure validated.(22)

Lentiviral vector construction, production and injection

Lentiviral constructs, production and injection were performed as described previously.(16) Lentiviral vectors are obtained as gifts from Dr. Didler Trono, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland. We first subcloned a 78 bp polylinker containing XhoI/SpeI/AscI/MluI/NdeI/BamHI/XmaI/XbaI sites into the PmeI site in pWPI to facilitate cloning. A ~500 bp PCR fragment containing the internal ribosome entry site of the Food and Mouth Disease Virus was then inserted into AscI/MluI sites as pWPI-IRES to enhance the translation of inserted cDNA. mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N, and mMOR-1K or mMOR-1L (exons 2/3/4) amplified by PCR using a sense primer flanked with MluI and an antisense primer flanked with XmaI were subcloned into MluI/XmaI sites of pWPI-IRES. pWPI-IRES-mMOR-1G was constructed as described previously.(16) The viral particles were generated in HEK293T cells by co-transfecting pWPI-IRES constructs with a packaging vector, PAX2, and an envelope vector, PMD2G, by using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Promega). After 24 hr transfection, the supernatants were collected, filtered, and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g, 2 hrs) in Beckman L7-55 ultracentrifuge. The viral titer of the concentrated lentiviral particles was determined by quantifying EGFP-expressing cells in transduced HEK293T cells with various dilutions using Tali Image-Based Cytometer (Invitrogen). Intrathecal (i.t.) injections were performed by lumbar puncture using a Hamilton 10 μl syringe fitted to a 30 gauge needle with PE-20 polyethylene tubing (Beckton-Dickinson) under general isofluane anesthesia (1–4%). 2 μl of the lentiviral particles expressing a 6TM variant or vector alone (~1.5 × 109 transducing units/ml) were i.t. administrated three times on days 1, 3, and 5.

Opioid analgesia

Analgesia was determined using the radiant-heat tail-flick assay, with a maximal latency of 10 sec to minimize tissue damage, as described previously.(16,19) Results were calculated as the percentage of maximum possible effect (% MPE) [(latency after drug − baseline latency)/(10 − baseline latency)*100]. Morphine or IBNtxA was administered subcutaneously (s.c.) at the indicated doses. Analgesia was assessed 30 min after injection at peak effect. Cumulative dose-response studies utilized escalating IBNtxA doses (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg), with the next higher dose administered immediately after analgesia testing of the previous dose. ED50 values with 95% confidence intervals were determined using nonlinear regression analysis using a two-parameter logistic model, a special case of the four-parameter logistic model with fixed the lower and upper asymptotes at 0% and 100% (GraphPad Prism). To examine levallorphan antagonism, the drug (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) was given 15 min prior to IBNtxA (2.5mg/kg, s.c.) and analgesia assessed 30 min after IBNtxA.

Reverse transcription and polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and SYBR green quantitative PCR (qPCR)

RNA isolation, RT-PCR and qPCR were performed as described previously.(16,23) Mice were euthanized by rapid cervical dislocation, and the lumbar and thoracic sections of the spinal cord were dissected for total RNA isolation. Total RNAs were isolated using RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) following manufactory’s protocol, treated with DNase I using Turbo DNA-free reagents (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed with Superscript III (Invitrogen) and random primers. The first-strand cDNAs were used in PCR to amplify a 402 bp fragment of exons 1–2 ((a sense primer (SP): 5′-GGC TCC TGG CTC AAC TTG TCC CAC-3′ and an antisense primer (AP): 5′-GGT GCA GAG GGT GAA GAT ACT GGT GAA C-3′)) for all 7TM variants, a 551 bp fragment of exons 2–3 (SP: 5′-GTA TCT TCA CCC TCT GCA CCA TGA GTG -3′ and AP: 5′-CGC ATA AAG AAC TGG GTT CAG GCA GC -3′) for both 7TM and 6TM variants, a 242 bp fragment of EGFP (SP: 5′-GGA CGG CAA CAT CCT GGG GC-3′ and AP: 5′-CGT TGG GGT CTT TGC TCA GGG C-3′) for lentivirus, and a 432 bp fragment of glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) (SP: 5′-ACC ACA GTC CAT GCC ATC AC-3′ and 5′-TCC ACC ACC CTG TTG CTG TA-3′) for RNA loading control. All PCR reactions were carried out in DNA Engine PTC-200 (Bio-Rad) using Plantium Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) for 35 cycles after 2 min at 94°C, each cycle consisting of a 20 sec denaturing step at 94°C, a 20 sec annealing step at 65°C (60°C for G3PDH) and 1 min extension at 72°C. PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and imaged using a ChemiDoc MP system (Bio-Rad). SYBR green qPCRs were performed in CFX96 machine (Bio-Rad) to amplify exons 2–3 (E2-3) using the above primers and HotStart Taq SYBR Green Master Mix (Affymetrix). After 2 min at 95°C, it run 50 cycles, each cycle containing a 15 sec denaturing step at 95°C, a 30 sec annealing step at 65°C (60°C for G3PDH) and 1 min extension at 72°C. Melting curve analysis was conducted subsequently. qPCR for G3PDH was used for normalization using 2−Δ(Ct) (ΔC(t) = C(t)E2-3 − C(t)G3PDH). Expression level (%) were calculated by normalizing with the mean of WT (Expression level = 2−ΔC(t) sample/2−ΔC(t) WT (the mean)*100. So the WT level is 100%.

Statistics

All mice were randomized and assigned to groups. Some, but not all, experiments were performed under blinded conditions. Data from qPCR, levallorphan and morphine analgesia studies were analyzed using 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test (GraphPad Prism). The time course of IBNtxA analgesia was analyzed using Repeated Measures Analysis of ANOVA. Data represented the means ± SEM of three or more independent samples. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

To examine the role of the individual 6TM variants in IBNtxA analgesia, we first made lentiviruses expressing mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N or mMOR-1K/L (i.e. exons 2/3/4) along with EGFP proteins for comparison with the earlier mMOR-1G lentivirus. The EGFP marker located downstream of the receptor cassette in each vector was co-translated through an encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) IRES, providing a marker of lentivirus expression. We then expressed these lentiviruses in the E1/E11-KO mice that lost both IBNtxA and morphine analgesia (Table 1) to see if these 6TM variants can rescue IBNtxA analgesia.

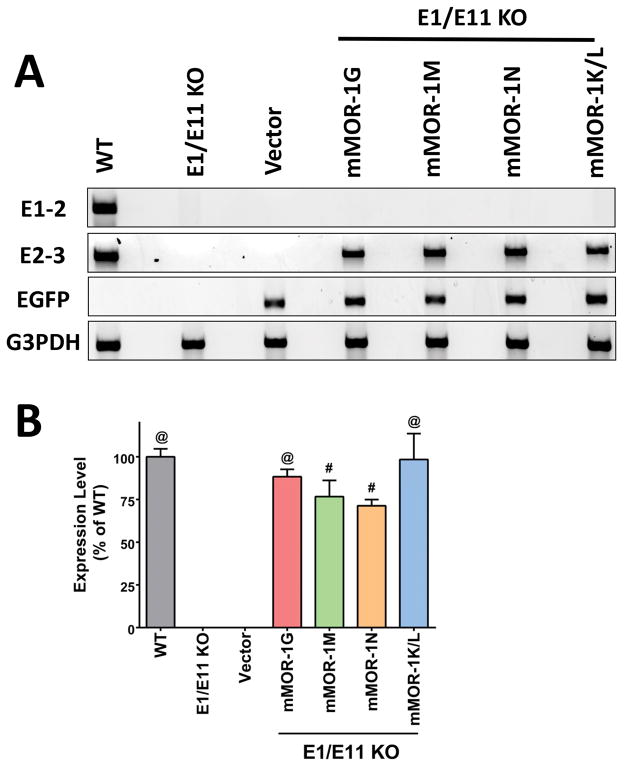

The mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N and mMOR-1K/L lentiviruses were administered spinally (i.t.) to the E1/E11-KO mice on days 1, 3, and 5, as previously described.(16,21) Lentivirus administered with paradigm achieved maximal expression after approximately 3–5 weeks and maintained similar expression levels for at least a year (unpublished observation). We included a mMOR-1G lentivirus group to provide a comparison with the new 6TM variants and to confirm our prior study. The EGFP mRNA was detected in all lentiviral transduced animals including lentiviral vector alone, confirming viral expression, but it was not found in the WT or KO controls (Fig. 2A). We examined mRNA expression of the specific 6TM variants with PCR using a pair of exon 2 and exon 3 (E2-3) primers to amply exons 2 and 3 mRNA since these primers will detect all the 6TM variants. All lentiviral 6TM transduced animals expressed the exons 2 and 3 mRNA, confirming expression of the individual 6TM variants in these animals (Fig. 2A). The expression level of the lentiviral 6TM variant mRNA was similar to that of WT controls (Fig. 2B). Untreated and vector-alone treated E1/E11 KO mice failed to reveal any PCR product, verifying the specificity of 6TM variant expression. No exon 1-associated 7TM variant transcripts using exon 1 and exon 2 (E1-2) primers were observed, confirming the lack of any full length 7TM mu opioid receptors in either KO or in any lenvirus transduced animals (Fig. 2A), proving lack of any 7TM variants in E1/E11 KO mice.

Figure 2. Expression of 6TM variant mRNAs transduced by lentivirus.

(A) Expression of 6TM variant mRNAs in the spinal cord by RT-PCR. Total RNAs from the spinal cord dissected after 34 weeks of lentiviral injection (mMOR-1G (n = 6), mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N and Vector (n = 4)) or 12 weeks (mMOR-1K/L (n = 6)) or WT or E1/E11 KO (n = 4) were used in RT-PCR in one experiment, as described in Methods. Representative PCR samples from 2% agarose gels were shown. (B) Quantification of 6TM variants by SYBR green qPCR. The same samples (n = 4–6/group) as described above were used in SYBR green qPCRs with the E2-3 primers in one experiment. Normalized expression was calculated as 2−ΔC(t) using G3PDH (ΔC(t) = C(t)variant − C(t)G3PDH). Expression levels (%) were calculated by normalizing with the mean of WT (Expression level = 2−ΔC(t) sample/2−ΔC(t) WT (the mean)*100. So the WT level is 100%. Compared to E1/E11 KO or Vector, #: p < 0.001; @: p < 0.0001 (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). There was no significant difference between WT and any of the 6TM variants.

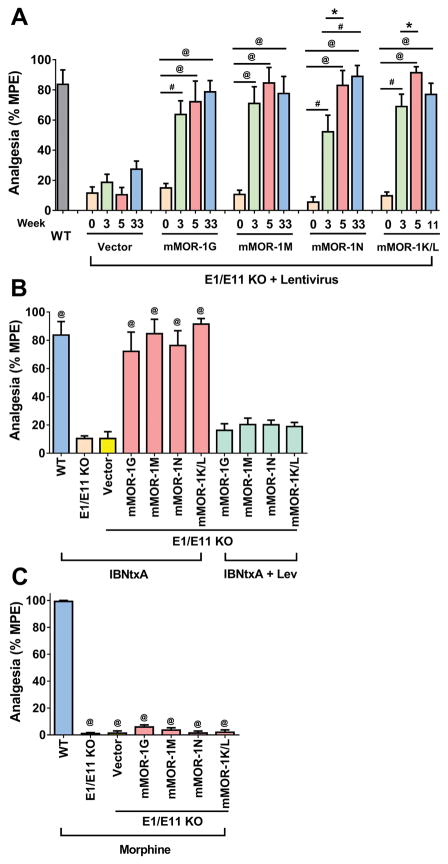

IBNtxA analgesia was assessed using a radiant-heat tail-flick assay. Untreated E1/E11 KO mice displayed no appreciable IBNtxA analgesia (Fig. 3A, Time 0), consistent with the absence of E11-associated 6TM variants (Table 1).(16) However, IBNtxA analgesia was fully restored in all 6TM lentivirus groups, starting 3 weeks after injection, with maximal responses remaining unchanged for the duration of the studies (Fig. 3A).(16) The results from lentiviral mMOR-1G group were consistent with those from the previous study,(16) providing a confirmatory replication. The effects of IBNtxA analgesia rescue in other three lentiviral 6TM groups were similar to that in Lentiviral mMOR-1G group, suggesting that all individual 6TM variants can restore IBNtxA analgesia. The vector alone failed to rescue IBNtxA analgesia (Fig. 3A) despite expression of the lentivirus alone, as indicated by expression of the EGFP marker (Fig. 2A). The 6TM did not affect morphine analgesia. Morphine remained totally inactive in all lentivirus-treated and in the E1/E11 KO mice (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Rescue of IBNtxA analgesia in E1/E11 KO mice.

(A) Time course of IBNtxA analgesia. Lentiviruses expressing mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M and mMOR-1N (n = 8) or mMOR-1K/L (n = 16) or Vector (n = 6) were i.t. administrated into E1/E11 KO mice, as described in Methods. WT mice (n = 6) were used as control at 0 week. IBNtxA analgesia (2.5 mg/kg, s.c. a dose greater than 4-fold ED50 in WT mice) was examined in indicated time before (0 week) or after the lentiviral injection in one experiment. Repeated measures ANOVA analysis showed a statistically significant effect of time (F(3,123) = 118.7, p < 0.0001), group (F(4, 41) = 13.34, p < 0.0001), and interaction of time*group (F(12, 123) = 5.38, p < 0.0001). For effect of time within a group, all four 6TM groups had a significant effect with p < 0.0001 except for Vector group, p = 0.4316. For pair-wise comparison across time within a group, *: p < 0.05; #: p < 0.001; @: p < 0.0001. (B) Effect of levallorphan on IBNtxA analgesia. IBNtxA analgesia without Levallorphan was assessed at 5 weeks after lentiviral injection (data including WT mice adapted from Fig. 3A). E1/E11 KO mice (n = 6) were included as a control. Levallorphan study was performed at 34 weeks (mMOR-1, mMOR-1M and mMOR-1N (n = 8) or 12 weeks (mMOR-1K/L (n = 16) after lentiviral injection in one experiment. Mice first received Levallorphan (2.5 mg/kg, s.c.) for 15 min and then IBNtxA (2.5mg/kg, s.c.) for 30 min before analgesia was assessed. Compared to untreated E1/E11 KO or Vector-injected or Levallorphan-treated mice, @: p < 0.0001 (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test). (C) Morphine analgesia. Morphine analgesia (10 mg/kg) was examined at 20 weeks (Vector (n = 6), mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M and mMOR-1N (n = 8)) or at 6 weeks (mMOR-1K/L (n = 16)) after lentiviral injection in one experiment. WT and E1/E11 KO mice (n = 6) were included as controls. Compared to WT, @: p < 0.0001 (1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc test).

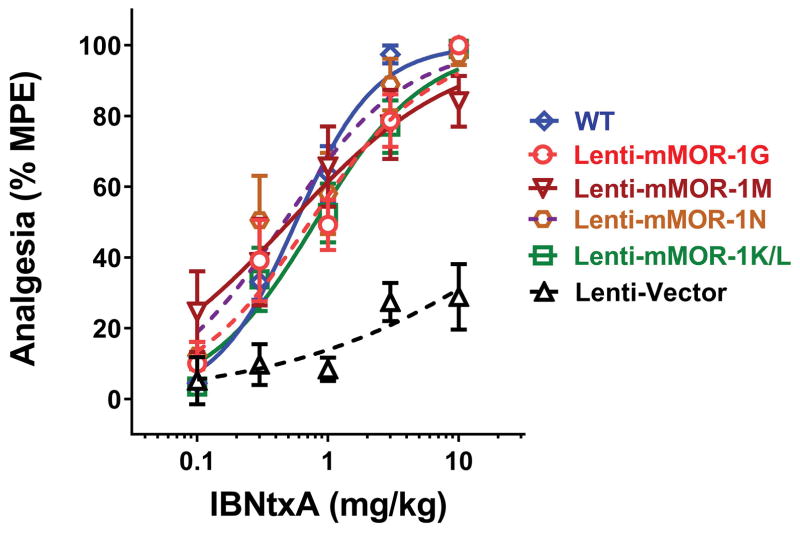

We then evaluated the rescued IBNtxA analgesia potency using cumulative dose-response curve study. Cumulative dose-response curve of lenti-mMOR-1G group revealed an ED50 value (0.73 mg/kg)(Fig. 4), which is similar to that (1.1 mg/kg) from the previous study (16), again providing a confirming replication. The other 6TM lentivirus groups, including mMOR-1M, mMOR-1N and mMOR-1K/L, had similar ED50 values (0.4–0.8mg/kg) that were indistinguishable from the WT control group (0.57 mg/kg; Fig. 4). Thus, the rescued mice regained full sensitivity towards IBNtxA. Vector treated E1/E11 KO mice displayed a small increased latency at high IBNtxA doses, similar to that previously observed,(16) raising the possibility that very high IBNtxA doses may lose their selectivity for 6TM mechanisms.

Figure 4. IBNtxA cumulative dose-response curve.

Cumulative dose response curve study was performed at 24 weeks (Vector (n = 6), mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M and mMOR-1N (n = 8)) or 9 weeks (mMOR-1K/L (n = 16)) after lentiviral injection. WT mice (n = 10) were included as a control. Various IBNtxA doses (0.1, 0.3, 1, 3 or 10 mg/kg) were s.c. administrated in a cumulative dosing paradigm in one experiment. ED50 values with 95% confidence intervals were determined using nonlinear regression analysis with log(agonist) vs. normalized response – Variable slope model (GraphPad Prism). IBNtxA ED50 values with 95% confidence interval (parentheses) were as follows: WT, 0.57 mg/kg (0.45,0.71); Lenti-G, 0.73 mg/kg (0.50, 1.1); Lenti-M, 0.5 mg/kg (0.22, 1.1); Lenti N, 0.46 mg/kg (0.28, 0.75); Lenti-K/L, 0.80 mg/kg (0.57, 1.1) and the vector control (Lenti-V) >10 mg/kg.

The sensitivity of IBNtxA analgesia to the opioid antagonist levallorphan confirmed the opioid nature of the response. We chose levallorphan based upon its higher affinity for the E11 binding site in brain than naloxone (1). All the rescued IBNtxA analgesia was blocked by levallorphan (Fig. 3B). Thus, 6TM variants are both necessary and sufficient for IBNtxA analgesia and are not involved with morphine actions.

Discussion

When first identified, the truncated 6TM variants presented an enigma. With a structure unlike traditional GPCRs, the functional relevance of these proteins was unclear. Knockout models provided the first suggestion that these variants were relevant.(1,19) Elimination of the 6TM variants in an E11 KO mouse had no appreciable effect on morphine or methadone analgesia, but eliminated IBNtxA analgesia (Table 1), illustrating the marked differences in receptor mechanisms between the two drugs. This was confirmed by the retention of IBNtxA analgesia in the E1 KO mouse that did not respond to morphine. However, the strongest evidence for the importance of 6TM variants in IBNtxA actions was provided by rescue studies.(16) Using the E1/E11 KO mouse, which does not express any Oprm1 gene products, intrathecal administration of a lentivirus expressing the 6TM mMOR-1G rescued IBNtxA, but not morphine, analgesia. mMOR-1G is one of five different 6TM variants (Fig. 1B), leaving open the question of whether the rescue was selective for mMOR-1G or would extend to all the 6TM variants.

Using a similar gain-of-function approach, the present study establishes the ability of four additional mouse 6TM variants to rescue IBNtxA analgesia. Each variant rescued the response, illustrating the utility of lentiviral-mediated gene delivery in studying individual Oprm1 splice variants in vivo. Structurally, all five E11-associated 6TM variants share a common core sequence encoded by exons 2 and 3 that comprises the 6 transmembrane domains, two intracellular loops, three extracellular loops and a portion of the intracellular C-terminal sequences (Fig. 1). They all are generated through the exon 11 promoter and their transcripts include exon 11, but alternative splicing yields differing N-terminal and C-terminal sequences. While mMOR-1G, mMOR-1M and mMOR-1N translate exon 11, mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L do not due to insertion of exon 13 or exon 14 between exons 11 and 2 that lead to early termination of translation in exon 13 (mMOR-1K) or 14 (mMOR-1L) when using the exon 11 AUG. Initiating translation with the AUG at the beginning of exon 2 yields a 6TM receptor without the N-terminal 27 amino acid sequences (MMEAFSKSAFQKLRQRDGNQEGKSYLR) encoded by exon 11. Therefore, mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L encode identical 6TM proteins.

The 6TM variants also undergo 3′ splicing with a range of alternative exons downstream of exon 3 (Fig. 1B). While mMOR-1G, mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L all contain exon 4, which encodes 12 amino acids (LENLEAETAPLP), the other two replace those 12 amino acids by either the 52 amino acids (PTLAVSVAQIFTGYPSPTHVEKPCKSCMDRGMRNLLPDDGPRQESGEGQLGR) encoded by exons 7/8/9 in mMOR-1M or with 7 amino acids (RNEEPSS) encoded by exon 8 in mMOR-1N.

Despite these different C-terminal or N-terminal sequences, all the variants rescued IBNtxA analgesia, suggesting that the C-terminal terminal differences and the exon 11 coding sequence have limited influence on their ability to restore IBNtxA analgesia. Although each of the variants is capable of rescuing the response, we still do not know whether a specific 6TM is responsible for IBNtxA activity in WT mice. Lentivirus transduction leads to a wide distribution of 6TM expression throughout the spinal cord when given intrathecally and throughout the brainstem and much of the brain when injected intracerebroventricularly.(16,21) While any of the 6TM variants may restore the response, they may not be acting in cells that normally express them. Regional mRNA studies showed marked differences in variant expression while immunohistochemical studies revealed cell-specific expression of C-terminal epitopes.(6,7) Thus, the specific variant(s) responsible for activity in WT mice remain unclear.

Our study confirms that 6TM variants are the only Oprm1 variants involved with IBNtxA analgesia, being both necessary and sufficient. Other opioid receptor classes also are not involved since IBNtxA analgesia remained intact in a ‘triple KO’ mouse lacking the full length exon 1-associated 7TM mu receptor variants as well as kappa and delta opioid receptors.(1) The inability of the 6TM variants to rescue morphine analgesia confirmed earlier studies reports (16, 19,20) demonstrating morphine’s dependence on only 7TM variants and provides additional evidence dissociating the receptor mechanisms of morphine and IBNtxA. Thus, 6TM variants represent novel targets for a distinct class of analgesics that have a superior pharmacological profile in view of their broad analgesic activity in thermal, inflammatory, and neuropathic pain models (3) coupled with the absence of respiratory depression, physical dependence, and reward behavior.(1)

Humans also express truncated 6TM OPRM1 variants.(4) Four 6TM variants, hMOR-1G1, hMOR-1G2, hMOR-1K and Mu3, have been identified in the human OPRM1 gene.(24–26) hMOR-1G2 is a homolog of mouse mMOR-1G, while hMOR-1G1, hMOR-1K and Mu3 utilize the exon 2 AUG to generate identical proteins analogous to mMOR-1K and mMOR-1L. Although the in vivo activity of these human 6TM variants remains unknown, the similarities to mouse splicing suggest they play a similar role in humans as in mice. This is supported by the clinical observations that opioids shown to be dependent upon exon 11 mechanisms in mice, such as buprenorphine,(27) are potent analgesics in humans.

The human splice variants also share other properties observed in mice. Prior studies revealed marked regional variations in expression for a range of mouse Oprm1-generated mRNAs.(23) Similarly, the expression of human 6TM variant mRNAs varies among brain regions (24). For example, hMOR-1G2 was highly expressed in the prefrontal cortex, piriform cortex, nucleus accumbens, pons and cerebellum, while it was less abundant in the spinal cord and temporal cortex.(24) hMOR-1G1 was only detected in the pons and cerebellum. Similarly, hMOR-1K expression was variable among the frontal lobe, nucleus accumbens, pons and spinal cord.(25)

Several single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the human OPRM1 gene regulate mu opioid receptor splice variant expression. An intronic SNP (rs9479757) associated with the severity of heroin addiction among Han-Chinese male heroin addicts modulates hnRNPH (a splicing factor) binding to promote exon 2 skipping, leading to altered expressions of 1TM variant mRNAs and MOR-1 proteins.(28) An A118G SNP (rs1799971) associated with heroin addiction and opioid responses altered expressions of MOR-1 mRNA and its protein.(29–31) A SNP (rs563649) located in the 5′untranslated region of a human 6TM variant, hMOR-1K, affects hMOR-1K expression at both the transcriptional and translational levels, and is associated with individual variations in pain perception.(25) These studies highlight genetic influences on gene expression involving OPRM1 alternative splicing that may contribute to the variable opioid responses in people.

Several technologies, such as RNAi, antisense oligonucleotide and clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9 endonuclease (CRISPR/Cas9), can be used to treat human diseases through modulation of gene expression. For example, an antisense oligonucleotide-based drug (SPINRAZA (nusinersen)) that corrects expression of Survival of motor neuron 2 (SMN2) gene has recently approved by US Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to treat Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) as the first-ever approved therapy for this disease. We recently used a vivo-morpholino oligonucleotide to selectively reduce expression of a set of mu opioid receptor C-terminal splice variants, leading to diminished morphine tolerance in mice.(17) Further exploring the molecular mechanisms of the regulation of 6TM variants expression would provide potential therapeutic targets for pain management in the future.

In conclusion, 6TM Oprm1 splice variants offer the potential of safer, effective analgesics. They illustrate the functional utility of truncated GPCR variants, which may extend beyond the opioid system. Truncated 6TM variants are not restricted to the OPRM1 gene. Over 6% of the human GPCR genes (excluding olfactory receptor genes) may potentially generate alternatively spliced 6TM variants based on genomic database analysis (unpublished observation). Our studies raise questions regarding the more general question of the pharmacological functions of truncated GPCR variants.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by grants from the Peter F. McManus Charitable Trust, Mr. William H. Goodwin and Mrs. Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, The Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and the National Institutes on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (DA06241 and DA07242) to GWP and (DA029244, DA013997 and DA04585) to Y-XP, a core grant from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (CA08748) to MSKCC and a National Natural Science Foundation of China (81673412) to ZGL.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: NONE

Author’s Contribution:

Name: Zhigang Lu, PhD. This author helped designing the experiments, conducting the study, analyzing the data and writing the manuscript.

Name: Jin Xu, MD. This author helped conducting the experiments and analyzing the data.

Name: Mingming Xu, MS. This author assisted conducting the experiments.

Name: Grace C Rossi, PhD. This author assisted conducting the experiments, analyzing the data and writing the manuscript.

Name: Susruta Majumdar, PhD. This author helped conducting the experiments.

Name: Gavril W Pasternak, MD/PhD. This author designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Name: Ying-Xian Pan, MD/PhD. This author designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Majumdar S, Grinnell S, Le RV, Burgman M, Polikar L, Ansonoff M, Pintar J, Pan YX, Pasternak GW. Truncated G protein-coupled mu opioid receptor MOR-1 splice variants are targets for highly potent opioid analgesics lacking side effects. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2011;108:19776–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115231108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majumdar S, Subrath J, Le Rouzic V, Polikar L, Burgman M, Nagakura K, Ocampo J, Haselton N, Pasternak AR, Grinnell S, Pan Y-X, Pasternak GW. Synthesis and evaluation of aryl-naloxamide opiate analgesics targeting truncated exon 11-associated mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) splice variants. JMedChem. 2012;55:6352–62. doi: 10.1021/jm300305c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wieskopf JS, Pan YX, Marcovitz J, Tuttle AH, Majumdar S, Pidakala J, Pasternak GW, Mogil JS. Broad-spectrum analgesic efficacy of IBNtxA is mediated by exon 11-associated splice variants of the mu-opioid receptor gene. Pain. 2014;155:2063–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasternak GW, Pan Y-X. Mu opioids and their receptors: Evolution of a concept. PharmacolRev. 2013;65:1257–317. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan EA, Abbadie C, Chang A, Zuckerman A, Rossi GC, Pasternak GW. Identification and characterization of three new alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor isoforms. MolPharmacol. 1999;56:396–403. doi: 10.1124/mol.56.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbadie C, Pan Y-X, Drake CT, Pasternak GW. Comparative immunhistochemical distributions of carboxy terminus epitopes from the mu opioid receptor splice variants MOR-1D, MOR-1 and MOR-1C in the mouse and rat central nervous systems. Neuroscience. 2000;100:141–53. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abbadie C, Pan Y-X, Pasternak GW. Differential distribution in rat brain of mu opioid receptor carboxy terminal splice variants MOR-1C and MOR-1-like immunoreactivity: Evidence for region-specific processing. JCompNeurol. 2000;419:244–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(20000403)419:2<244::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolan EA, Pan Y-X, Pasternak GW. Functional characterization of several alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) isoforms. SocNeurosci. 2000;26:112. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caron MG, Bohn LM, Barak LS, Abbadie C, Pan Y-X, Pasternak GW. Mu opioid receptor spliced variant, MOR1D, internalizes after morphine treatment in HEK-293 cells. SocNeurosci. 2000;26:783.3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan YX, Xu J, Bolan E, Chang A, Mahurter L, Rossi G, Pasternak GW. Isolation and expression of a novel alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor isoform, MOR-1F. FEBS Letters. 2000;466:337–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Antisense mapping: Assessing functional significance of genes and splice variants. Methods in Enzymology: Antisense Technology, Pt B. 2000;314:51–60. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)14094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Y-X, Xu J, Mahurter L, Bolan EA, Xu MM, Pasternak GW. Generation of the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) protein by three new splice variants of the Oprm gene. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2001;98:14084–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241296098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbadie C, Pan Y-X, Pasternak GW. Immunohistochemical study of the expression of exon11-containing mu opioid receptor variants in the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2004;i:419–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Pan YX, Kolesnikov Y, Pasternak GW. Immunohistochemical labeling of the mu opioid receptor carboxy terminal splice variant mMOR-1B4 in the mouse central nervous system. Brain Res. 2006;1099:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu Z, Xu J, Xu M, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Morphine regulates expression of mu-opioid receptor MOR-1A, an intron-retention carboxyl terminal splice variant of the mu-opioid receptor (OPRM1) gene via miR-103/miR-107. MolPharmacol. 2014;85:368–80. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.089292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu Z, Xu J, Rossi GC, Majumdar S, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Mediation of opioid analgesia by a truncated 6-transmembrane GPCR. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:2626–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI81070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu J, Lu Z, Narayan A, Le Rouzic VP, Xu M, Hunkele A, Brown TG, Hoefer WF, Rossi GC, Rice RC, Martinez-Rivera A, Rajadhyaksha AM, Cartegni L, Bassoni DL, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Alternatively spliced mu opioid receptor C termini impact the diverse actions of morphine. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1561–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI88760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu J, Xu M, Brown T, Rossi GC, Hurd YL, Inturrisi CE, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Stabilization of the mu opioid receptor by truncated single transmembrane splice variants through a chaperone-like action. JBioChem. 2013;288:21211–27. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.458687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan YX, Xu J, Xu M, Rossi GC, Matulonis JE, Pasternak GW. Involvement of exon 11-associated variants of the mu opioid receptor MOR-1 in heroin, but not morphine, actions. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2009;106:4917–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811586106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuller AG, King MA, Zhang J, Bolan E, Pan YX, Morgan DJ, Chang A, Czick ME, Unterwald EM, Pasternak GW, Pintar JE. Retention of heroin and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia in a new line of mice lacking exon 1 of MOR-1. NatNeurosci. 1999;2:151–6. doi: 10.1038/5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marrone GF, Grinnell SG, Lu Z, Rossi GC, Le Rouzic V, Xu J, Majumdar S, Pan YX, Pasternak GW. Truncated mu opioid GPCR variant involvement in opioid-dependent and opioid-independent pain modulatory systems within the CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:3663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523894113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majumdar S, Burgman M, Haselton N, Grinnell S, Ocampo J, Pasternak AR, Pasternak GW. Generation of novel radiolabeled opiates through site-selective iodination. BioorgMedChemLett. 2011;21:4001–4. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu J, Lu Z, Xu M, Rossi GC, Kest B, Waxman AR, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Differential Expressions of the Alternatively Spliced Variant mRNAs of the mu Opioid Receptor Gene, OPRM1, in Brain Regions of Four Inbred Mouse Strains. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e111267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu J, Xu M, Hurd YL, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Isolation and characterization of new exon 11-associated N-terminal splice variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene. JNeurochem. 2009;108:962–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shabalina SA, Zaykin DV, Gris P, Ogurtsov AY, Gauthier J, Shibata K, Tchivileva IE, Belfer I, Mishra B, Kiselycznyk C, Wallace MR, Staud R, Spiridonov NA, Max MB, Goldman D, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: novel functional variants. HumMolGenet. 2009;18:1037–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cadet P, Mantione KJ, Stefano GB. Molecular identification and functional expression of mu 3, a novel alternatively spliced variant of the human mu opiate receptor gene. JImmunol. 2003;170:5118–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grinnell SG, Ansonoff M, Marrone GF, Lu Z, Narayan A, Xu J, Rossi G, Majumdar S, Pan XY, Bassoni DL, Pintar J, Pasternak GW. Mediation of buprenorphine analgesia by a combination of traditional and truncated mu opioid receptor splice variants. Synapse. 2016;70:395–407. doi: 10.1002/syn.21914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Lu Z, Xu M, Pan L, Deng Y, Xie X, Liu H, Ding S, Hurd YL, Pasternak GW, Klein RJ, Cartegni L, Zhou W, Pan YX. A heroin addiction severity-associated intronic single nucleotide polymorphism modulates alternative pre-mRNA splicing of the mu opioid receptor gene OPRM1 via hnRNPH interactions. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11048–66. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3986-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Sadee W. Allelic Expression Imbalance of Human mu Opioid Receptor (OPRM1) Caused by Variant A118G. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:32618–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mague SD, Isiegas C, Huang P, Liu-Chen LY, Lerman C, Blendy JA. Mouse model of OPRM1 (A118G) polymorphism has sex-specific effects on drug-mediated behavior. ProcNatlAcadSciUSA. 2009;106:10847–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901800106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bond C, LaForge KS, Tian MT, Melia D, Zhang SW, Borg L, Gong JH, Schluger J, Strong JA, Leal SM, Tischfield JA, Kreek MJ, Yu L. Single-nucleotide polymorphism in the human mu opioid receptor gene alters β-endorphin binding and activity: Possible implications for opiate addiction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:9608–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]