Abstract

Pain is a clinical hallmark of sickle cell disease (SCD), and is rarely optimally managed. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for pain has been effectively delivered through the Internet in other pediatric populations. We tested feasibility and acceptability of an Internet-delivered CBT intervention in 25 adolescents with SCD (64% female, Mage=14.8years) and their parents randomized to Internet CBT (n=15) or Internet Pain Education (n=10). Participants completed pre-/post-treatment measures. Eight dyads completed semi-structured interviews to evaluate treatment acceptability. Feasibility indicators included recruitment and participation rates, engagement and adherence to intervention, and completion of outcome measures. Eighty-seven referrals were received from nine study sites; our recruitment rate was 60% from those families approached for screening. Among participants, high levels of initial intervention engagement (>90%), and adherence (>70%) were demonstrated. Most participants completed post-treatment outcome and diary measures (>75%). Retention at post-treatment was 80%. High treatment acceptability was reported in interviews. Our findings suggest that Internet-delivered CBT for SCD pain is feasible and acceptable to adolescents with SCD and their parents. Engagement and adherence were good. Next steps are to modify recruitment plans to enhance enrollment and determine efficacy of Internet CBT for SCD pain in a large multi-site randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: Sickle Cell Disease, Child, Adolescent, Pain, Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Internet

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD) is the most common childhood genetic blood disease in North America, primarily affecting youth of African American descent1. A clinical hallmark of SCD is acute recurrent vaso-occlusive episodes of pain1,2. However, many young people with SCD also experience ongoing chronic pain3,4. The presence of pain in youth with SCD has been associated with a range of psychosocial consequences including depression, anxiety and stress, poor sleep, decreased social interaction, and increased school absenteeism5-8. More frequent SCD pain also negatively impacts health-related quality of life8-11. Painful crises are the main reason for SCD-related hospitalization6, and drive annual healthcare costs of $1.1 billion12. Pain burden increases with age as youth with SCD move through childhood into adolescence and young adulthood13, which emphasizes the importance of early intervention to teach pain self-management skills to minimize the negative consequences of chronic pain.

Despite known consequences of experiencing SCD pain, pain is rarely optimally managed14,15. The first line of treatment for SCD pain is standard medical therapy, primarily opioids. However, medication alone has not been effective in reducing pain burden or associated psychosocial consequences in youth with SCD16. Psychological therapies for pain management such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) have been shown effective in reducing pain and improving coping skills and health-related quality of life in both youth with SCD pain and other chronic pain conditions17-19. CBT for pain involves the normalization of the pain experience through education about pain, training in behavioral and cognitive strategies for managing pain and disease-related symptoms, enhancing self-efficacy, and guidance on developing and maintaining a long-term self-management plan17,18,20.

While there is support for the use of CBT for pain, most youth with SCD do not have access to these treatments. Barriers to delivery include geographic restrictions to CBT pain services, limited availability of clinicians trained in CBT for SCD pain, the direct and indirect incurred costs of additional healthcare visits to receive CBT21,22, and the stigma associated with seeking assistance through mental health services23.

The use of Internet-delivered interventions is a potential option to overcome barriers to accessing pain management services for youth with SCD and their families. Evidence from a systematic review showed that treatments delivered on the Internet reduce pain and disability in youth with other types of chronic pain24 and of these interventions, CBT has been found to be most effective25. Access to Internet and smartphone technologies among African Americans is high (79%), even among those of low income26, thus the Internet appears a viable platform to offer an intervention.

To our knowledge, only one prior technology-based intervention has been developed and evaluated for youth with SCD pain27. In this study, a sample of children and adolescents with SCD were provided with one in-person session of CBT followed by 8 weeks of home-based practice using a smartphone, with weekly clinician phone contact. The effectiveness of this intervention was compared to a wait-list control. In comparison to the control group, participants who received CBT believed they had more control over their pain, but had no change in their negative thinking in response to pain or in their pain intensity. The smartphone application was underutilized (average use of only 12% over the 8-weeks), and the coping skills section of the application was accessed on less than a quarter of the total pain days reported by all youth. The results of this study highlight the importance of designing an intervention that youth with SCD will engage with and adhere to for learning pain coping skills.

In our prior work on internet-delivered pain management interventions in other populations of youth with chronic pain, we have had success in engaging youth and their parents in CBT through a program called Web-MAP28 with promising effects on reductions in pain-related disability. Because there is no research to date on the feasibility and efficacy of an Internet-delivered pain management intervention for youth with SCD, our first step was to apply our available program (Web-MAP) to determine the feasibility of use in this population. Specifically, we sought to 1) examine the feasibility of recruitment, randomization to CBT vs education control, and completion of daily diary and outcome measures in this population, and 2) assess engagement with and adherence to Web-MAP in adolescents with SCD pain and their parents.

We hypothesized that the program would be feasible to administer, as evidenced by completion of over 70% of the modules and a level of engagement with the program similar to that seen in our prior work with Web-MAP in youth with other chronic pain conditions29,30. We also evaluated the acceptability of the online CBT program using qualitative methods to understand whether modification of the intervention would be required to meet the needs of youth with SCD in a larger trial. We expected that families would perceive the program as acceptable for adolescents with SCD pain and their parents but may also have suggestions for tailoring and adapting the program to more specifically meet their needs. Although outcome measures were collected, the purpose of their inclusion was to assess completion rates pre- and post-treatment rather than to test treatment efficacy, which was not possible given our small sample size. In this pilot study, our goal was to test all procedures (i.e., screening, recruitment, intervention delivery, outcome assessment) in order to inform the conduct of a larger randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered pain management in this population.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants included 25 adolescent-parent caregiver dyads. Inclusion criteria were (a) diagnosis of SCD, (b) age between 11-18 years, (c) a score of > 3 on the Sickle Cell Pain Burden Interview-Youth (SCPBI-Y13), (d) access to the internet on a computer or smartphone, and (e) a parent/caregiver who could participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were: (a) did not speak English as a primary language, or (b) attended > 4 outpatient psychological therapy sessions for pain management in the 6 months prior to screening.

Procedure

For this pilot study we tested a multi-center recruitment strategy with providers at nine sickle cell clinics in the United States. Providers made families aware of the study through a flyer and asked if they would be willing to be contacted. If verbal consent for further contact was given, providers entered potential participants' contact information into the secure study website to transfer referral information to research staff at the first author's institution. Interested families then underwent telephone screening with research staff to determine eligibility and to obtain assent from youth and consent from parent caregivers. Enrolled families were emailed a secure link to complete study procedures online.

Upon study enrollment, adolescents and parents completed a battery of pre-treatment measures on demographics, pain disability, burden and catastrophizing, depressive symptoms, and health-related quality of life. Adolescents were also asked to complete a daily diary to rate pain intensity and activity limitations over seven days. All assessments and the daily diary were completed online via REDCap. Following completion of pre-treatment measures, adolescent-parent dyads were block randomized to one of two treatment conditions: internet-delivered CBT (active treatment), or internet-delivered pain education (control). Adolescents and parents in both conditions were provided with access to different versions of an online program “Web-based Management of Adolescent Pain” (Web-MAP) that provided either the CBT or pain education treatment. Full descriptions of both the CBT and pain education versions of Web-MAP have been described elsewhere30. Following completion of the Web-MAP online program, participants completed post-treatment questionnaires and adolescents completed the 7-day daily diary.

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with a subset of adolescent-parent dyads, assigned to the CBT condition. These participants were chosen using a computer generated randomization table. The interview focused on preferences for treatment, acceptability of the Web-MAP program and content, and relevance of the program for SCD pain. Interviews were conducted by a member of the research team, were audio taped and lasted approximately 30 minutes.

Research staff maintained ongoing contact with families during the course of their participation, to remind families about post-treatment assessments and to answer any questions. Following the completion of measures at each assessment point (pre-treatment, post-treatment), adolescents and parents both received $50 gift cards. The Institutional Review board at all sites approved this study.

Internet-delivered CBT

Participants in the CBT condition had access to treatment modules on the Web-MAP web site. Adolescents and parents were asked to individually log onto the website weekly, complete the treatment modules to learn cognitive and behavioral skills, and complete behavioral assignments to consolidate these skills. There were a total of eight modules for adolescents and parents each to complete that covered education about pain, instruction in relaxation strategies, cognitive strategies, healthy lifestyle, and operant strategies for modifying parent responses to pain to support adaptive behaviors. Information in each module is presented through videos, vignettes, activities and illustrations. Adolescents and parents can interact with the program by typing in information and answering questions throughout the modules. For example, in module 1, all participants are asked to specify goals for the treatment. The information that participants enter into each module is used to tailor the behavioral assignments attached to that module. Communication between participants and the research team occurred through a message center embedded in Web-MAP. Participants could contact their online study therapist at any stage during the treatment and study therapists would communicate with participants after the completion of each assignment. There were three study therapists, one had a Master's degree and two were PhD level psychology postdoctoral fellows with training and experience in providing CBT. Study therapists were supervised by the first author, a licensed clinical psychologist with experience in CBT for pediatric pain management and in clinical intervention with youth with SCD.

Internet-delivered pain education

Participants in the internet pain education condition were also asked to log onto Web-MAP weekly. They had access to the pain education version of the Web-MAP study website, which included information from publicly available websites about pediatric chronic pain management. The pain education version of the website differed from the one accessed by the CBT treatment condition in that there was no access to cognitive and behavioral skills training via treatment modules for adolescents and parents, nor were there behavioral assignments to complete. Throughout the study, adolescents in both groups continued to receive standard medical care from their sickle cell care team.

Screening Measure

Sickle Cell Pain Burden Interview-Youth (SCPBI-Y)

Adolescents and parents independently completed the SCPBI-Y13. The SCPBI-Y contains seven items to assess the impact of pain on physical, emotional and social aspects of daily living for youth with SCD, over the previous month. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale regarding the number of days pain has affected daily living (0 = none, 4 = every). Responses are summed to create a total score ranging from 0-28, with higher scores indicating greater severity of pain burden. The SCPBI-Y has demonstrated strong reliability and validity. Adolescents who scored > 3 during screening were eligible to participate in the trial.

Treatment feasibility

WebMAP use and engagement

Across both the CBT and pain education groups, data from the administrative backend of the web platform provided number of logins, modules opened and completed, and program completion time. For purposes of this pilot study, we defined engagement in the intervention as percentage of patients completing at least one module in the WebMAP program. Adherence to the intervention was defined as completion of 6 or more modules of WebMAP.

Results

Participant characteristics

Participants included 25 adolescents between 11-18 years of age (M=14.8, SD=2.1), and their parents. Adolescents were primarily female (64%) and African-American with Hemoglobin SS or Sc genotypes. Mothers were the predominate caregiver involved in the study and annual household income primarily fell between $10,000-$29,999. See Table 1 for the full details of participant characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of sample, by treatment group and combined.

| CBT | Patient Education | Combined sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N, M(SD), n(%) | N, M(SD), n(%) | N, M(SD), n(%) | |

| N | 15 | 10 | 25 |

| Age (years) | 14.5 (2.1) | 15.2 (2.0) | 14.8 (2.1) |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 10 (66.7%) | 6 (60%) | 16 (64%) |

| Male | 5 (33.3%) | 4 (40%) | 9 (63%) |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Black or African American | 14 (93.3%) | 9 (90%) | 23 (92%) |

| >1 race | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (8%) |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 13 (86.7%) | 7 (70%) | 20 (80%) |

| Other | 1 (6.7%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (16%) |

|

| |||

| Annual household income | |||

| < $10,000 | 1 (6.7%) | 2 (20%) | 3 (12%) |

| $10,000 - $29,999 | 3 (20%) | 7 (70%) | 10 (40%) |

| $30,000 - $49,999 | 7 (46.7%) | 0 | 7 (28%) |

| $50,000 - $69,999 | 3 (20%) | 0 | 3 (12%) |

| $70,000 - $99,999 | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (10%) | 2 (8%) |

|

| |||

| Sickle Cell Genotype | |||

| SS | 10 (66.7%) | 7 (70) | 17 (68%) |

| Sc | 3 (20%) | 1 (10%) | 4 (16%) |

| S Beta Thal + | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

| S Beta Thal o | 0 | 2 (20%) | 2 (8%) |

| Unsure | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

|

| |||

| Taking Hydroxyurea | |||

| Yes | 6 (40%) | 8 (80%) | 14 (56%) |

| No | 9 (60%) | 2 (20%) | 11 (44%) |

|

| |||

| Regular blood transfusions | |||

| Yes | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (10%) | 9 (24%) |

| No | 10 (66.7%) | 9 (90%) | 16 (76%) |

|

| |||

| Caregiver involved in study | |||

| Mother | 14 (93.3%) | 9 (90%) | 23 (92%) |

| Father | 1 (6.7%) | 0 | 1 (4%) |

| Grandmother | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

Feasibility

Recruitment and randomization

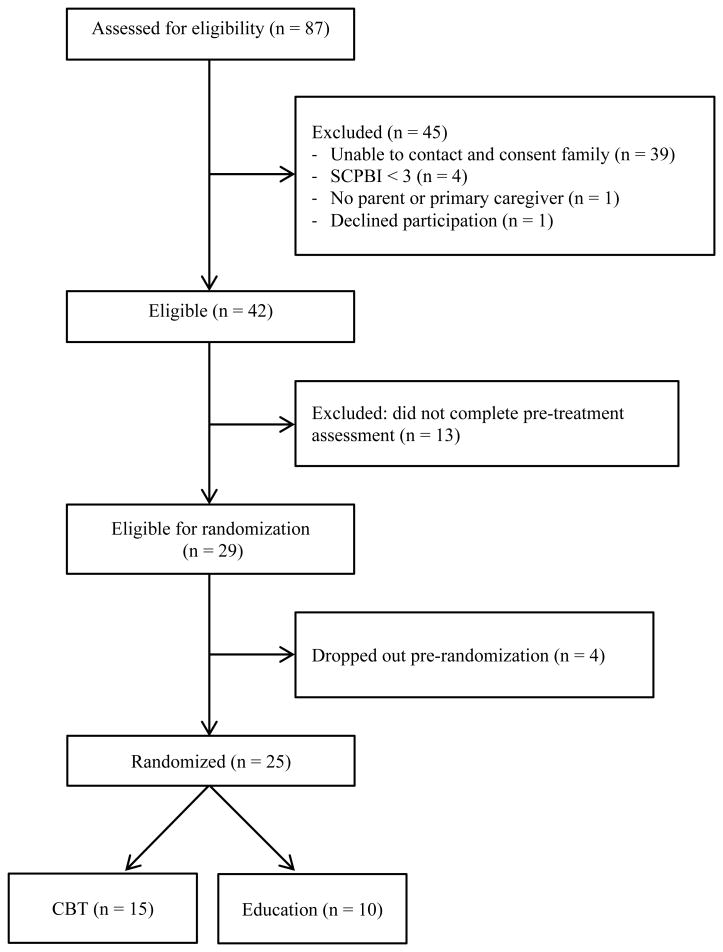

Figure 1 shows a CONSORT flow diagram depicting recruitment flow of study participants. From the nine referring centers, 87 families were referred. The number of referrals per recruitment site varied, ranging from 1 to 29. Of the families who were referred, 45 were excluded for the following reasons: unable to be contacted by phone (n=39), did not meet inclusion criteria (SCPBI < 3, n=4; no primary caregiver, n=1), and declined participation (n=1). Due to the high number of families who could not be reached by phone, 45% of referrals were unable to be screened. Of the remaining 42 eligible participants, 13 did not complete the pre-treatment assessments (passive refusal). Twenty-nine participants were therefore eligible for randomization. Four participants dropped out pre-randomization leaving a final sample of 25 participants. This equated to a recruitment rate of 60% from approached participants and 29% from all referrals. The final sample of 25 participants were enrolled and randomized to either Internet CBT (n=15) or Internet pain education (n=10). At post-treatment, 3 adolescents dropped out of the CBT group and 2 adolescents dropped out of the Pain Education group for a retention rate at post-treatment of 80%.

Figure 1. Study recruitment flow (CONSORT chart).

Completion of outcome measures and daily diaries

Assessment completion was high with 91.3% of all adolescent-parent dyads completing all measures both pre- and post-treatment. In the CBT group, 100% (n=15) of adolescents completed the pre-treatment questionnaires and daily diaries. Post-treatment, 80% (n=12) of adolescents completed the questionnaires, 86.6% (n=13) completed daily diaries. All parents (n=15) in the CBT group completed the pre-treatment measures and 80% (n=12) completed the post-treatment questionnaires.

Similar rates of completion of measures were seen in the Education group; 100% (n=10) of adolescents completed the pre-treatment questionnaires and daily diaries. Post-treatment, 80% completed the questionnaires and daily diaries. All parents (n=10) in the education group completed the pre-treatment measures, and 90% (n=9) completed the post-treatment measures.

Treatment engagement and adherence

Across both the CBT and education groups, there were high levels of initial engagement (>90%) and good adherence to the interventions, with over 70% of all participants completing 6/8 modules. In the CBT group, 93% (n=14) of adolescents engaged with the intervention, 80% (n=12) adhered to the intervention, and 73.3% (n=11) completed the intervention. The number of modules completed ranged from 0-8 (M=6.5, SD=2.9). During treatment, adolescents logged into WebMAP approximately 15.2 times (SD=9.4, range = 2-38). All parents (n=15) in the CBT group engaged with the intervention, 74.4% (n=11) adhered by completing 6/8 modules, and 66.7% (n=10) completed the intervention. The number of modules completed by parents in the CBT group ranged from 1-8 (M=6.4, SD=2.7). During treatment, parents logged into WebMAP a mean of 16.4 times (SD=9.7, range = 3-43). Program completion time for the adolescent-parent dyad ranged from 7-15 weeks, with a mean completion time of 11.3 weeks (SD=2.7).

In the education group, 90% (n=9) of adolescents engaged with, and adhered to, the intervention and 80% completed all 8 modules. The number of modules completed ranged from 0-8 (M=7.1, SD=2.5). Throughout the course of the intervention, adolescents in the education group logged into WebMap an average of 6.8 times (SD=3.6, range = 0-12). All parents (n=10) in the education group engaged with the intervention, and there was a 90% adherence and completion rate. The number of modules completed ranged from 3-8 (M=7.5, SD=1.6). The average number of parent logins to WebMAP was 9.7 (SD=5.4, range = 1-21). Program completion time for the adolescent-parent dyad ranged from 11-12 weeks, with a mean completion time of 12.1 weeks (SD=0.4).

Acceptability

Eight adolescent-parent dyads were contacted, and agreed, to be interviewed on their overall experience and perception of WebMAP. Two interviews were conducted with non-completers and six were conducted with dyads who completed all eight modules. From the qualitative data that were collected, the program was generally perceived as convenient and easy to use, and the content was described as understandable and interesting (e.g., “It was very easy to go through… self-explanatory format”). Participants shared their thoughts on how to improve the program. For example, some said they would like more images and diagrams to complement the text. Others wanted the program to be available through mediums other than the Internet, such as a smartphone application. Accessing WebMAP via only the Internet was mentioned as a barrier for both the non-completers interviewed.

Participants highlighted the number of varied skills they were taught and the applicability of the skills for both managing SCD-related pain and general daily life issues, e.g. “There are things you can learn that you can use pretty much every day”. There was no indication that participants thought the skills were not tailored towards adolescents with SCD. The majority of participants interviewed who completed the program would recommend it to other children with SCD and their families, e.g. “I would definitely recommend it to people with the same condition as my daughter…it's very helpful information that you can apply and help make pain better and manage”.

Discussion

The overall goal of this project was to determine program feasibility and inform methodology to conduct a large multi-center RCT of Internet-delivered CBT for youth with chronic SCD pain. To achieve this goal, our first aim was to examine the feasibility of recruitment, randomization to treatment conditions, and outcome measure completion. While recruitment rates were lower than desirable primarily due to difficulties reaching families by phone, we demonstrated feasibility of using multi-center referral from nine SCD clinics. The majority of families who could be reached were willing to participate and be randomized. Youth who participated in the study demonstrated a high rate of compliance with completion of outcome measures, including a daily online diary. Our second aim was to examine rates of initial engagement and continued adherence to the Internet-delivered treatment conditions. Both intervention engagement and adherence to interventions were excellent with over 70% of youth and caregivers adhering to the treatment modules. Retention was high at post-treatment at 80%. The engagement and adherence rates seen in the current study are comparable to the rates reported in previous WebMAP intervention studies in other pediatric pain populations29-31. The final aim was to assess acceptability of the program for a SCD population. Although a generic chronic pain management program was presented, youth and caregivers found it beneficial. However, suggestions were provided for tailoring and adapting the program for SCD specifically.

CBT interventions that promote pain self-management can lead to symptom reduction, improved health-related quality of life, and decreased healthcare use19,32,33. However, many youth never develop critical pain self-management skills during childhood and are ill prepared to cope with SCD pain as adults, during which time pain often becomes more severe and persistent. Chronic pain in SCD is just beginning to receive research attention. Historically, the focus of clinical management has been on treating acute pain due to vaso-occlusive crises. More recently, chronic pain has been identified as a substantial problem in individuals with SCD4, highlighting the need for more effective intervention approaches to address this particular need. Indeed young people with SCD describe a lack of available resources to support pain self-management34. Thus, there is a critical need for innovative programs targeting youth with chronic SCD pain.

Adolescents with chronic SCD pain experience psychosocial and functional impact similar to youth with other types of chronic pain35. In children and adolescents, SCD pain is associated with increased impairment in daily activities such as school 36,37, physical activities, social activities, and sleep quality38, as well as reduced health-related quality of life 39. The content of our CBT pain intervention targets these primary areas of pain impact and include such strategies as teaching youth to set goals for activity participation, manage school-related issues, change negative thinking patterns, implement relaxation-based strategies, and improve sleep habits. Youth and parents desired more disease-specific education about SCD which can be incorporated into a tailored version of the intervention, specifically for this population. However, the same general CBT strategies found effective for reducing pain-related disability in other populations of youth with chronic pain29,30 were also perceived as relevant and useful in youth with SCD pain.

Given the challenges that can arise with uptake of technology-based interventions, we prioritized this pilot study to understand issues with intervention delivery and trial design in order to optimize a future larger RCT of internet-delivered CBT in youth with SCD chronic pain. The only prior study27 to use technology in this population to deliver CBT skills was limited by a low recruitment rate (13% of referrals and 30% among those approached) and very low patient engagement with the intervention (only 12% used skills). Thus, we were sensitive to possible challenges in recruitment and intervention delivery. Our findings demonstrated that our Internet-delivered CBT intervention program had good engagement from participants, was adhered to, and was acceptable to adolescents with SCD chronic pain and their parents, showing promise to study this intervention further in a larger trial. We believe the intervention was engaging to youth because it makes use of a narrative, uses tailoring and personal accountability, and is interactive with multi-media elements.

Similar to other intervention studies in youth with SCD, the most significant challenge was recruitment. Despite referrals from all nine recruitment sites, our available pool was relatively small, and many families could not be contacted by phone (45% of families referred). Among families who we were able to screen for eligibility we had further passive refusal by failure to complete assessments. Thus our overall recruitment rate from referrals was 29% while our recruitment rate from those approached was 60%. In other studies in the sickle cell population, similar and lower rates of recruitment (13-49%) have been reported27,40,41. Indeed a key barrier identified to participation in intervention studies by patients with SCD is scheduling study visits. Our procedures, which involved entirely phone and online consent, assessment, and treatment effectively removed the logistical barriers to participating in treatment studies in person. However, unreliable internet service did contribute to some participation problems for several families. We believe our experiences with recruitment reflect the significant challenges of enrolling African American youth and their parents into intervention research where broader socioeconomic barriers, mistrust and misunderstanding of research, and lack of perceived benefits from research participation, and chaotic home organization may explain low enrollment. As a point of comparison, recruitment rates were significantly higher (70-80%) in our previous studies using the WebMAP intervention29-31 recruiting predominantly Caucasian youth attending tertiary care chronic pain and headache clinics. Further, there were site-specific differences in referrals and enrollment. This may reflect differences in patient populations at each site who have differing levels of engagement in, or knowledge of, research. It may also reflect differences in the experience of staff at each site in research participation. Regional socioeconomic factors may also play a role in the ability to contact patients by phone or email.

We agree with recommendations of others concerning strategies that may improve recruitment and retention in this population, such as reducing demands on participants, offering study incentives, and remaining in contact via phone and reminders 41. From our experiences in this pilot RCT, we add to this list several additional recommendations including: 1) obtaining at least three contact numbers for individuals who will know how to reach the patient, 2) requesting permission to send text message reminders, and 3) offering multiple intervention formats including mobile and web-based versions of the intervention. In addition, we are considering additional methods to engage staff at referring clinic sites (e.g., developing a webinar about the study, visiting sites in person). It will be important prior to dissemination of this intervention to also gain information directly from health care providers at the clinics to understand possible barriers and facilitators to implementation of an internet-delivered CBT pain management intervention to youth with SCD pain.

Given the very limited availability of non-pharmacological pain interventions to individuals with SCD, technology may be a key tactic to deliver pain self-management programs more broadly. Our preliminary findings showed that youth with SCD and their parents will engage and adhere to a technology-delivered pain self-management intervention. Future studies to determine efficacy of internet-delivered pain self-management are a critical next step.

Acknowledgments

Source of funding: This study was supported by a grant from the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving (WTZ). TMP is supported by NIH K24HD060068.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. American journal of preventive medicine. 2010 Apr;38(4 Suppl):S512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franck LS, Treadwell M, Jacob E, Vichinsky E. Assessment of sickle cell pain in children and young adults using the adolescent pediatric pain tool. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2002 Feb;23(2):114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Heart L, and Blood Institute. Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease: Export panel report, 2014. Bethesda, MD: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dampier C, Palermo TM, Darbari DS, Hassell K, Smith W, Zempsky W. AAPT Diagnostic Criteria for Chronic Sickle Cell Disease Pain. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2017 Jan 05; doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2016.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shapiro BS, Dinges DF, Orne EC, et al. Home management of sickle cell-related pain in children and adolescents: natural history and impact on school attendance. Pain. 1995 Apr;61(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00164-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gil KM, Carson JW, Porter LS, et al. Daily stress and mood and their association with pain, health-care use, and school activity in adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003 Jul-Aug;28(5):363–373. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benton TD, Ifeagwu JA, Smith-Whitley K. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Current psychiatry reports. 2007 Apr;9(2):114–121. doi: 10.1007/s11920-007-0080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sil S, Cohen LL, Dampier C. Psychosocial and Functional Outcomes in Youth With Chronic Sickle Cell Pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2016;32(6):527–533. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dampier C, Shapiro BS. Management of Pain in Sickle Cell Disease. In: Schechter NL, Berde CB, editors. Pain in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 489–516. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conner-Warren RL. Pain intensity and home pain management of children with sickle cell disease. Issues in comprehensive pediatric nursing. 1996 Jul-Sep;19(3):183–195. doi: 10.3109/01460869609026860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonner MJ. Health related quality of life in sickle cell disease: Just scratching the surface. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2010;54(1):1–2. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kauf TL, Coates TD, Huazhi L, Mody-Patel N, Hartzema AG. The cost of health care for children and adults with sickle cell disease. American journal of hematology. 2009 Jun;84(6):323–327. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zempsky WT, O'Hara EA, Santanelli JP, et al. Validation of the sickle cell disease pain burden interview-youth. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2013 Sep;14(9):975–982. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dampier C, Ely E, Brodecki D, O'Neal P. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: a daily diary study in children and adolescents. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2002 Nov;24(8):643–647. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stinson J, Naser B. Pain management in children with sickle cell disease. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(4):229–241. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200305040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunlop RJ, Bennett KC. Pain management for sickle cell disease. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006 Apr 19;(2):Cd003350. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003350.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher E, Heathcote L, Palermo TM, de CWAC, Lau J, Eccleston C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological therapies for children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014 Sep;39(8):763–782. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palermo TM, Eccleston C, Lewandowski AS, Williams AC, Morley S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological therapies for management of chronic pain in children and adolescents: an updated meta-analytic review. Pain. 2010 Mar;148(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen E, Cole SW, Kato PM. A review of empirically supported psychosocial interventions for pain and adherence outcomes in sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004 Apr-May;29(3):197–209. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eccleston C, Williams ACdC, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009;(2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007407.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng P, Choiniere M, Dion D, et al. Challenges in accessing multidisciplinary pain treatment facilities in Canada. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2007 Dec;54(12):977–984. doi: 10.1007/BF03016631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng P, Stinson JN, Choiniere M, et al. Dedicated multidisciplinary pain management centres for children in Canada: the current status. Can J Anaesth. 2007 Dec;54(12):985–991. doi: 10.1007/BF03016632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barlow JH, Ellard DR. Psycho-educational interventions for children with chronic disease, parents and siblings: an overview of the research evidence base. Child: care, health and development. 2004 Nov;30(6):637–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velleman S, Stallard P, Richardson T. A review and meta-analysis of computerized cognitive behaviour therapy for the treatment of pain in children and adolescents. Child: care, health and development. 2010 Jul;36(4):465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher E, Law E, Palermo TM, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2015 Mar 23;3:CD011118–CD011118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011118.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zickuhr K, Smith A. Home Broadband 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schatz J, Schlenz AM, McClellan CB, et al. Changes in coping, pain, and activity after cognitive-behavioral training: a randomized clinical trial for pediatric sickle cell disease using smartphones. Clin J Pain. 2015 Jun;31(6):536–547. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long AC, Palermo TM. Brief report: Web-based management of adolescent chronic pain: development and usability testing of an online family cognitive behavioral therapy program. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009 Jun;34(5):511–516. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Peters M, Lewandowski A, Somhegyi H. Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. Pain. 2009 Nov;146(1-2):205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palermo TM, Law EF, Fales J, Bromberg MH, Jessen-Fiddick T, Tai G. Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral treatment for adolescents with chronic pain and their parents: a randomized controlled multicenter trial. Pain. 2016 Jan;157(1):174–185. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Law EF, Beals-Erickson SE, Noel M, Claar R, Palermo TM. Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Internet-Delivered Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Pediatric Headache. Headache. 2015 Nov-Dec;55(10):1410–1425. doi: 10.1111/head.12635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gil KM, Anthony KK, Carson JW, Redding-Lallinger R, Daeschner CW, Ware RE. Daily coping practice predicts treatment effects in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001 Apr-May;26(3):163–173. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas VJ, Gruen R, Shu S. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the management of sickle cell disease pain: identification and assessment of costs. Ethnicity & health. 2001 Feb;6(1):59–67. doi: 10.1080/13557850123965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stinson JN, Lalloo C, Kirby-Allen M, et al. Exploring the pain self-management needs of adolescents with sickle cell disease to inform development of a web-based educational intervention. 15th World Congress on Pain. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palermo TM. Impact of Recurrent and Chronic Pain on Child and Family Daily Functioning: A Critical Review of the Literature. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2000;21(1):58–69. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwartz LA, Radcliffe J, Barakat LP. Associates of school absenteeism in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009 Jan;52(1):92–96. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dyson SM, Abuateya H, Atkin K, et al. Reported school experiences of young people living with sickle cell disorder in England. British Educational Research Journal. 2010;36(1):125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Valrie CR, Gil KM, Redding-Lallinger R, Daeschner C. Brief Report: Sleep in Children with Sickle Cell Disease: An Analysis of Daily Diaries Utilizing Multilevel Models. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(7):857–861. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palermo TM, Schwartz L, Drotar D, McGowan K. Parental report of health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease. J Behav Med. 2002 Jun;25(3):269–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1015332828213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schlenz AM, Schatz J, Roberts CW. Examining Biopsychosocial Factors in Relation to Multiple Pain Features in Pediatric Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2016;41(8):930–940. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barakat LP, Schwartz LA, Salamon KS, Radcliffe J. A family-based randomized controlled trial of pain intervention for adolescents with sickle cell disease. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2010 Oct;32(7):540–547. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181e793f9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]