Abstract

Gay and bisexual men (GBM) have reported viewing significantly more sexually explicit media (SEM) than heterosexual men. There is some evidence that SEM depicting bareback anal sex may be linked to engagement in condomless anal sex (CAS) and thus HIV/STI transmission among GBM. A nationwide sample of HIV-negative GBM in the U.S. completed an online survey that included measures on SEM consumption (both overall frequency and percentage viewed depicting bareback sex) and reported on CAS in the past 3 months. Data showed that there was no main effect for the frequency of SEM watched in association on either the number of CAS acts with casual partners or the probability of engaging in CAS during a casual sex event. However, there was an interaction between amount of SEM consumed and percentage of bareback SEM consumed on both outcomes, such that men who reported both a high frequency of SEM consumption and a high percentage of their SEM being bareback reported the highest levels of risk behavior. These findings highlight the role that barebacking depicted in SEM may play in the normalization of sexual risk behaviors for GBM. Interventions looking to target the role SEM may play in the lives of GBM should examine what variables may help to mediate associations between viewing SEM and engaging in risk behavior.

Keywords: gay and bisexual men, sexually explicit media, pornography, HIV, condomless anal sex

Introduction

Gay and bisexual men (GBM) continue to be disproportionately affected by HIV in the United States.1,2 Despite efforts to slow the rate of infection, GBM made up 67% of new infections in 2015, 84% of those among men; an increase of 12% since 2008.1,3 Sexually explicit media (SEM) has received some attention and exploration as a possible variable in contributing to sexual risk behaviors that increase risk for HIV infection. GBM are estimated to consume 33-50% of all SEM in the U.S.4,5 despite making up around 4% of the total population.6,7 Consumption of SEM is highly acceptable within the gay community8-11 and can have many positive effects for GBM, including serving as a source of sexual education (as most sexual education in the U.S. is heteronormative) and sexual identity exploration and confirmation.12-15 A recent content analysis of SEM featuring MSM reported that anal sex appeared in 70% of the films viewed. Of those, approximately half depicted anal sex without condoms.16 A popular website used to locate gay SEM reported in 2016 that of the 36 major gay SEM production companies, only eight produced SEM exclusively featuring condoms during anal sex—down from eighteen in 2013.17 Taken together, and with various limitations, these reports suggest that SEM featuring condomless anal sex (CAS) is widely available and may also be on the rise. If SEM produced for GBM continues to reduce the use of condoms for anal sex, it is important to understand the potential impact SEM may have on the behavior of GBM. It is possible that SEM is contributing to CAS among SEM consumers by presenting CAS as normative and expected behavior for GBM.

The connection between SEM and CAS has been investigated with GBM, but the conclusions have varied somewhat. One study reported that GBM who watch more SEM in general tend to engage in more CAS,18 though it is more often reported that overall consumption does not influence CAS and the type of SEM viewed if more important (i.e. with or without condoms). For example, Schrimshaw, Antebi-Gruszka, and Downing19 conducted as online survey of 265 GBM and concluded that overall consumption of SEM did not predict CAS, but viewing a greater proportion of bareback SEM was associated with more CAS acts. The differences in these two studies findings may be the location for the samples. The first sample consisted of only GBM living in Atlanta, whereas the second included GBM from 4 major metropolitan cities. Somewhat similarly, utilizing a diverse sample of 751 non-monogamous GBM living in NYC, Stein, Silvera, Hagerty, and Marmor20 reported that the percentage of bareback SEM consumed was positively associated with CAS—those who watched 75-100% bareback SEM compared to those who watched 0-24% reported significantly higher odds of having recently engaging in both insertive and receptive CAS. Although the Stein et al.20 sample consisted of only those located in NYC, similar findings were replicated with a national sample of GBM. Utilizing a national sample of 1,170 GBM, Nelson et al.21 reported increased odds of engaging in CAS when 25% or more of the SEM they consumed depicted bareback sex.

Two other studies have examined SEM and CAS behavior in GBM among national samples. Rosser et al.,22 reported that of their sample of 1,391 MSM, those who reported a preference for bareback SEM also reported higher odds of engaging in risk behavior. Træen et al.,23 examined the same sample and reported that those who viewed more bareback SEM also engaged in more sexual risk behavior. Additionally, they also found that condom use self-efficacy mediated this relationship. One critique of the above mentioned national samples is the collecting of the bareback SEM consumption variable as categorical and reporting of sexual risk behavior as binary. Although these studies do provide valuable information about this at-risk population, they are potentially leaving out nuanced differences among the findings.

There are two theories that may help to explain the association between SEM and CAS for GBM. The first being Social Learning Theory,24 which in short states that people are surrounded by many influential models for behavior that may include friends, peer groups, or media and that these models set the standards for acceptable and expected behaviors. Media may be of heightened significant importance for young GBM who do not have friends or peer groups who they feel they identify with. As such, a lack of adequate comparisons in main stream media may lead GBM to look to SEM for models of behavior.

SEM depicts sexual behavior that lead to only positive outcomes (e.g. pleasure, connection, and orgasm) while ignoring other possible outcomes (e.g. STI and HIV transmission). Thus, GBM who consume large amount of SEM depicting bareback sex may see more benefits to bareback sex and associate that behavior with more positive outcomes, without being aware that other forms of risk reduction may be taking place (i.e. pre-exposure prophylaxis, treatment as prevention, status disclosure, strategic positioning, etc.). Attention to behavior that is viewed as having more positive than negative outcomes leads to retention of behavior followed by reproduction of the behavior and ultimately motivation to continue the behavior. As such, viewers of large percentages of bareback SEM may perceive that engaging in CAS is normative and leading to sexual gratification or more rewards than using condoms, thus leading to motivation for engaging in CAS.

Although Social Learning Theory may help to explain initial learning and engagement in CAS for some GBM, it is possible that GBM who prefer to engage in CAS may also simply prefer to watch SEM depicting their preferred behavior. The second theory, Reinforcement Theory,25 may help to explain the reversed causal pathway in the association between viewing larger percentages of bareback SEM and engaging in more CAS. Reinforcement Theory states that behavior is shaped by environmental factors and behaviors that are viewed as having positive consequences are increased in frequency. For GBM engaging in CAS, there may be an interaction between viewing their own behavior as having positive consequences and seeing the behavior mirrored back with positive consequences via SEM. Thus, leading to a stronger belief in the positive outcomes of engagement in CAS, and increasing the frequency.

In this study, we sought to replicate and expand on current findings by examining the association between bareback SEM consumption and sexual risk behavior. Prior research has examined both large and national samples of GBMSM, however we aimed to improve on the ways SEM and bareback SEM consumption has previously been reported in two ways. Firstly, by collecting SEM consumption data, including percentage bareback, as a continuous variable as opposed to categorically. Secondly, by reporting on both the number of CAS events or partners, and also the odds of engaging in CAS for each anal sex act using the same sample. We will be testing two models, one that examines viewing bareback SEM and number of CAS acts, the other on viewing bareback SEM and the odds of engaging in CAS for any given anal sex act. In our first model we hypothesize there will be no main effect for SEM consumption on number of casual CAS acts, there will be a main effect for the percentage of bareback SEM and number of casual CAS acts, and there will be an interaction effect for amount of SEM consumed and percentage that is bareback SEM on the number of casual CAS acts such that those who watch larger percentages of SEM depicting bareback anal sex will have engaged in more casual CAS acts. In our second model we hypothesize that there will be no main effect for SEM consumption on the odds of engaging in CAS for each anal sex act, there will be a main effect for the percentage of bareback SEM consumed on odds of engaging in CAS for each anal sex act, and there will be an interaction effect for the amount of SEM consumed and percentage that is bareback SEM on the odds of engaging in CAS for each anal sex act such that those who watch higher percentages of bareback SEM will have higher odds of engaging in CAS for each anal sex act.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

One Thousand Strong is a longitudinal study prospectively following a panel of 1,071 HIV-negative GBM from across the US for a period of three years from 2014-2017.26-28 Potential participants were identified from a panel of over 22,000 GBM via Community Marketing and Insights (CMI). The panel recruited by CMI is comprised of individuals drawn from over 200 sources (e.g., lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender events, e-mail broadcasts distributed by LGBT organizations, main stream media, and social media). Initially, via e-mail 9,011 individuals were invited to complete the screening survey. Those sent the screening survey were identified potential eligible having met the criteria of 18 years or older, identified as a gay or bisexual male, and had regular internet access.

Of the eligible men, 1,071 (77.9%) completed all requirements and were enrolled into the cohort. The goal for recruitment was to collect a sample which approximates the United States population by using data on the density of same-sex households via the U.S. Census in terms of age, geographic location, and race and ethnicity composition. All participants were at least 18 years of age, biologically male, identified as male, identified as gay or bisexual and were HIV-negative. In addition to their self-identification, all participants reported having sex with a man in the past year. As part of the One Thousand Strong cohort, participants are sent an on-line completer assisted self-interviewing (CASI) survey every 12-months, with additional optional surveys sent at 6-months, 18-months, and 30-months. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York's Human Research Protections Program.

Analyses for this study are cross-sectional and were performed on the 12-month data, in which participants completed an online CASI survey that included the SEM measures for the present analyses.

Measures

Demographic and background characteristics

Participants reported demographic characteristics including race/ethnicity, education, income, age, relationship status, sexual orientation, U.S. zip come, and current PrEP prescription status (currently prescribed versus not currently prescribed).

Overall SEM consumption

Participants responded to two questions about SEM consumption. The first question “Have you watched porn (sexually explicit videos, Internet streaming, downloaded, DVD, etc.) in the last 3 months?” Two reply options were given, “yes” and “no”. Those who answered “yes” were then asked “On average, how many hours per week do you watch porn (sexually explicit videos, Internet streaming, downloaded, DVD, etc.)?” Data for the second question were collected as a continuous variable. Because the distribution of the number of hours of SEM watched was positively skewed, the responses were ranked and normalized using the Rankits algorithm in SPSS, an established methodology for ranking and normalizing data.29 The data are first ranked and then the ranks are transformed in such a way that well-approximates a normal or Gaussian distribution, maintaining the original ordering of the data while losing the information contained within the absolute difference in the original variable. The rank-normalized SEM consumption variable was then used for all statistical analyses, and will simply be referred to as overall SEM consumption throughout.

Bareback SEM consumption

Participants were asked “How would you describe the porn you watched in the last 3 months?” Responses were provided via a sliding scale ranging from “0% - all condoms” to “100% - all bareback” And an additional option that read “not applicable: I have not watched porn featuring anal/vaginal sex in the last 3 months.

Condomless anal sex acts

In order to gather information on sexual risk behaviors participants were first asked “How many casual male sexual partners have you had in the last 3 months? (by sex, we mean any sexual contact that could lead to an orgasm).” Secondly, they were then asked how many times they engaged in condomless anal sex with each of those partners over the last 3 months. The total number of all acts was used in the analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics for variables of interest were examined, including demographics (e.g. age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, income, employment, education, geographic region, and sexual orientation), and overall SEM consumption. To examine the frequency of CAS encounters with casual male partners, we utilized a negative binomial regression with the dispersion parameter freely estimated. To model the probability of CAS during a given sex event, we utilized a Poisson regression of the number of casual CAS acts with an offset equal to the log of the number of casual anal sex acts.30 Both models contained main and interaction effects for overall SEM consumption and the percentage of bareback SEM (both mean-centered to reduce multicollinearity), and both models were adjusted for the effects of age, race/ethnicity, education attainment, income, and relationship status. Additionally, we adjusted for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use as those who are currently taking PrEP may view their sexual behavior differently in terms of risk than those not currently taking PrEP. Significant interactions were plotted holding covariates constant at their means and looking at levels of the predictors at 1 standard deviation above and below their means.

Results

Of the 1,017 (94.9%) that completed the 12-month CASI, 4 (0.004%) reported being HIV-positive, 77 (7.6%) had not watched SEM in the last 3 months, 44 (4.3%) had not watched SEM containing anal/sex in the last 3 months, and 346 (34%) had not had any casual male sex partners, leaving an analytic sample of 546. Most of the sample was White (71.0%), employed full-time (72.5%), and self-identified as gay (95.4%) (Table 1). This sample was diverse in regards to age, education, income, geographic region, and relationship status. The average age of this sample was 40.8 (SD = 13.68, range = 19-76). The average hours of SEM consumption in terms of hours per week was 3.49 (SD = 4.92; range 0-72), which we then rank-normalized into a new variable used in all analyses (M = 275, SD = 156.09). Participants reported the average percentage of their SEM consumed that depicted bareback anal sex was 59.75% (Mdn. = 59, SD = 27.15). The number of men that reported having watched no bareback SEM was 12 (2.2%) whereas 47 (8.6%) reported watching exclusively bareback SEM. The number of participants who reported having engaged in CAS with a casual male partner was 312 (31.9%). Of those who had engaged in CAS with a casual partner, the average number of CAS acts in the last three months was 6.82 (Mdn = 3, SD = 10.77, range 1-96).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics.

| Full Sample (N= 546) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| n | % | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 44 | 8.1 |

| Latino | 60 | 11.0 |

| White | 387 | 70.9 |

| Other/multiracial | 55 | 10.1 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay | 524 | 96.0 |

| Bisexual | 22 | 4.0 |

| Education | ||

| High school degree of less | 27 | 4.9 |

| Some college or Associate's degree | 191 | 35.0 |

| 4-year College Degree or more | 328 | 60.1 |

| Income | ||

| Less than $20k per year | 81 | 14.8 |

| $20k to 49k per year | 208 | 38.1 |

| $50k to $74k per year | 108 | 19.8 |

| $75k or more per year | 149 | 27.3 |

| Employment | ||

| Unemployed | 73 | 13.4 |

| Part-time | 76 | 13.9 |

| Full-time | 397 | 72.7 |

| Geographic Region | ||

| Northeast | 116 | 21.2 |

| Midwest | 94 | 17.2 |

| South | 182 | 33.3 |

| West | 154 | 28.2 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 345 | 63.2 |

| Partnered | 201 | 36.8 |

| Currently on PrEP | ||

| Yes | 68 | 12.5 |

| No | 478 | 87.5 |

We ran a series of ANOVAs to test for demographic differences in overall SEM consumption. Results indicated no differences between average weekly SEM consumption and age, race, sexual orientation, education, income, employment, relationship status, PrEP use, and geographic region. Similarly, results assessing differences between percentage of bareback SEM consumed showed no differences in terms of age, race, sexual orientation, education, income, employment status, and geographic region. However, there was a significant difference in percentage of bareback SEM consumed between single (M = 57.96, SD = 27.68) and partnered men (M = 62.86, SD = 25.88) such that partnered men reported viewing higher percentages of bareback SEM, t(544) = 2.04, p = 0.04. Additionally, there was a significant difference in percentage of bareback SEM consumed between those currently taking PrEP (M = 71.44, SD = 25.71) and those not currently taking PrEP (M = 58.10, SD = 26.92) such that those currently on PrEP reported viewing higher percentages of bareback SEM, t(544) = 3.85, p < .00.

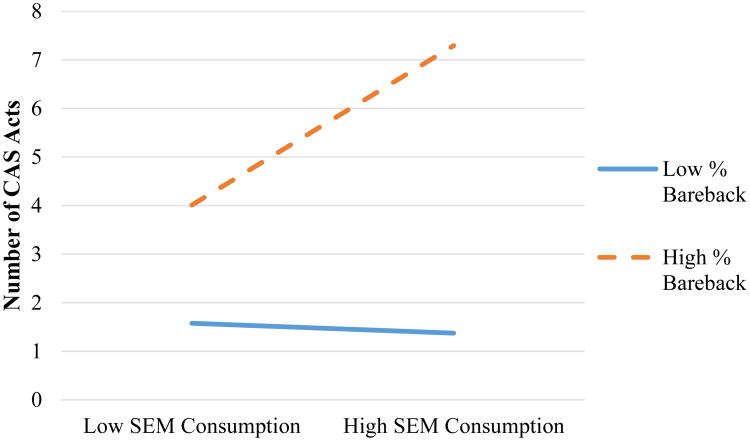

Predicting frequency of CAS with Casual Male Partners

Utilizing a negative binomial model, we examined our hypothesis that there would be no main effect for SEM consumption on the number of casual CAS acts, a main effect for the percentage of bareback SEM consumed on casual CAS acts, and an interaction effect such that those who viewed a higher percentage of bareback SEM in the last three months would have engaged in more CAS acts with casual male partners in the last three months—results are displayed as Model 1 within Table 2. Results indicated no main effect of overall SEM consumption on number of CAS acts with casual partners (adjusted rate ratio [ARR]) = 1.10). However, there was a main effect of the percentage of bareback SEM consumed on the number of CAS encounters with casual partners (ARR = 1.03), such that a 1% increase in bareback SEM was associated with a 3% increase in the rate (i.e., frequency) of CAS with casual partners. As hypothesized, there was a statistically significant interaction between overall SEM consumption and the percentage of bareback SEM viewed on the number of CAS casual partners (ARR = 1.01) and this interaction is plotted in Figure 1. The main effect of percentage of bareback SEM consumption is evidenced by the line for men with high percentages of bareback SEM consumption corresponding to higher frequency of CAS. Moreover, the significant interaction is easily seen among the group of men for whom the majority of their SEM is bareback, as the more SEM they watch, the higher frequency of CAS they have.

Table 2. Effects for SEM and BB SEM Consumption.

| Model 1: Frequency of CAS1 | Model 2: Probability of CAS2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| B | Exp (B) | 95% CI | B | Exp (B) | 95% CI | |

| Age | 0.01 | 1.01* | 1.00, 1.03 | 0.01 | 1.01*** | 1.00, 1.01 |

| White race (ref. yes) | 0.06 | 1.06 | 0.77, 1.49 | 0.12 | 1.13* | 1.02, 1.25 |

| 4-year college degree (ref. yes) | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.73, 1.39 | -0.06 | 0.94 | 0.86, 1.03 |

| Income 20k or less (ref. >50k) | -0.39 | 0.68 | 0.43, 1.06 | -0.27 | 0.77*** | 0.68, 0.86 |

| Income 21-50k (ref. >50k) | -0.48 | 0.62* | 0.39, 0.96 | -0.23 | 0.80*** | 0.71, 0.90 |

| Relationship (ref. single) | -0.13 | 0.88 | 0.65, 1.21 | -0.03 | 0.97 | 0.88, 1.07 |

| Currently on PrEP (ref. yes) | 0.79 | 2.20*** | 1.45, 3.43 | 0.12 | 1.13* | 1.03, 1.25 |

| SEM consumption | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.96, 1.32 | -0.04 | 0.96 | 0.91, 1.14 |

| Percentage BB consumption | 0.02 | 1.03*** | 1.02, 1.03 | 0.02 | 1.02*** | 1.01, 1.02 |

| SEM × Percentage BB consumption | 0.01 | 1.01* | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.00 | 1.00** | 1.00, 1.01 |

p <.001,

p <.01,

p <.05

Note:

Frequency of CAS refers to the total number of casual CAS acts and is modeled in a negative binomial regression;

Probability of CAS in any given casual sex encounter is modeled using a Poisson regression of the total number of casual CAS acts with an offset equal to the log number of anal sex events.

Figure 1.

The varying number of CAS acts engaged in for those that viewed differing amounts of overall SEM for both low and high bareback SEM consumers.

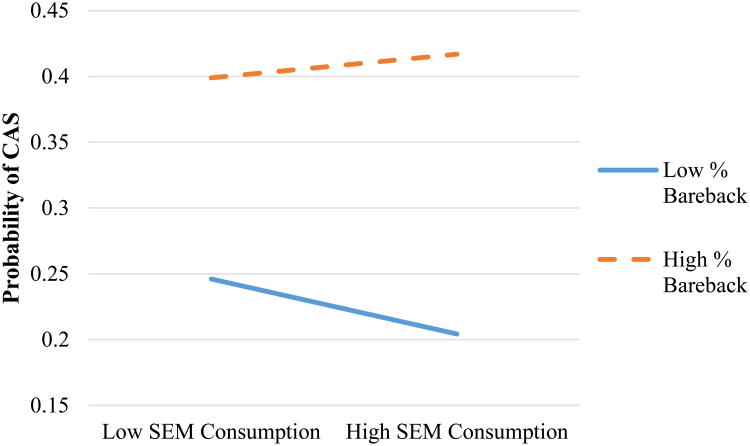

Predicting probability of CAS with Casual Partners

Next we conducted a Poisson regression model with an offset to determine the rate of CAS with a male casual partner per anal sex event (i.e., the probability of CAS during a given anal sex act), with the results being displayed in Model 2 of Table 2. Consistent with the findings regarding the frequency of CAS, overall SEM consumed did not have a significant main effect on the probability of engaging in CAS with casual male partners (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.95)). The percentage of bareback SEM consumed did have a significant main effect (AOR = 1.02), such that a 1% increase in bareback SEM consumption was associated with a 2% increase in the odds of CAS during a given sexual-event. There was also a significant interaction between overall SEM consumed and percentage of bareback SEM consumed (AOR = 1.00), which is plotted in Figure 2. As can be seen, more overall SEM consumption is protective for men who watch a low percentage of bareback SEM and risk-enhancing for men who watch a high percentage of bareback SEM.

Figure 2.

The probability of engaging in CAS during any anal sex encounter for those that viewed differing amounts of overall SEM for both low and high bareback SEM consumers.

Discussion

We found that the amount of SEM GBM viewed by itself was not significantly associated with the number of CAS acts with casual partners or the probability of engaging in CAS during an anal sex act. In contrast, viewing bareback SEM was associated with both a higher number of CAS acts and the probability of engaging in CAS during an anal sex act. In both models there was an interaction effect for overall SEM consumed and the percentage that was bareback SEM such that those who viewed larger amounts and percentages of bareback SEM had more casual CAS acts and were more likely to engage in CAS during any anal sex act. To the best of our knowledge, no other study examining bareback SEM and behavior has reported on the probability for each act.

These findings are largely analogous to other findings.19-21,23 In addition to replicating their findings, we utilized continuous variables, which allowed us to build onto past research by predicting both the number of CAS acts and the probability of engaging in CAS at each sex act. Other researchers have reported an outcome of either an individual's dichotomously engaging in sexual risk or not, and because of their work we are now able to dig deeper into these associations and determine not only if risk occurred, but how much.

There is however, one study whose findings do not match with those presented by us or other researchers. Eaton et al.,18 reported that watching larger amounts of any SEM is associated with more sexual risk. We and other researchers did not find a direct connection between any SEM consumption and CAS acts without considering the percentage of bareback CAS viewed. Some reasons for differences may be that the Eaton et al.,18 study only reported frequency of SEM consumption and a requirement to participate in their study was having reported two or more male unprotected anal sex partners in the last six months. This leaves out a question of the type (with or without condoms) of SEM consumed and ensures that these participants are already engaging in some sexual risk. Another reason for the difference in findings may be due to location sampling. Eaton et al.,18 utilized a sample all residing in Atlanta, GA, whereas others utilized multiple metropolitan cities,19,20 or, like ourselves, were national samples.21-23

With the addition of our findings to those of other researchers, and the fact that the pornography industry is likely to continue expanding and SEM become more accessible, it is imperative that research looking to understand sexual risk behavior among GBM target how GBM are learning about not only HIV prevention methods, but also about sexual expectations from SEM. One mediator of bareback SEM and CAS that has been examined in literature with some success is condom use self-efficacy, which has been shown to by higher among GBM that view SEM depicted condoms for anal sex and lower in GBM who view bareback SEM.23 Although these findings suggest that viewing SEM depicting condom use may influence viewers to also use condoms, it does not address that some viewers may not watch SEM that utilizes condoms or that condom use in gay SEM is rapidly declining. Findings from one large study of over 1,000 GBM suggest that as many as 83% of SEM viewers would be accepting of safer sex messaging being included in SEM.31 Acceptable messaging highly endorsed among this sample included the viewing of condom and lubrication application and viewing of a scene in which the actors discuss condom use. These researchers also reported that of the 17% of their sample that did not find any safer sex messaging acceptable, they were also more likely to engage in CAS. These findings suggest two things. Firstly, the majority of viewers find safe sex messaging to be acceptable, but it is unclear to what extent. Since the majority of SEM currently viewed is online, it may be important for researchers to assess the acceptability of viewing safer-sex messaging before the video that includes both behavioral and biomedical strategies (i.e. 15-second condom use tutorials or PrEP advertising). Secondly, more covert messaging (i.e. actors seen taking PrEP) may be important for some high risk individuals that do not find any form of safer-sex messaging acceptable. The acceptability of PrEP and TasP in SEM among high risk GBM has not yet been established.

Additionally, another area of intervention could address SEM viewer's thoughts around condom use as being the only prevention technique and acknowledge that while bareback SEM may appear to be “unprotected” other risk prevention methods may be being utilized (i.e. PrEP, serosorting, treatment as prevention, etc). An intervention assessing the interpretation of SEM and beliefs about the reality of sex for young GBM may be important. It is important that any intervention around SEM to not diminish the positive aspect of SEM consumption. GBM have an increase in sexual knowledge, sexual pleasure, physical sexual functioning, and sleep improvement.12-14,23 Overall, GBM have reported SEM as having a positive effect on their lives.13

It is imperative that when researching the effects of SEM that the type of SEM viewed is addressed, which may go further than SEM featuring bareback sex. There is a variety of SEM available and someone who views exclusively bareback SEM may not have the same outcomes or behaviors as someone who only watches solo (i.e. masturbation, toys, etc.) or oral SEM. The majority of research on this topic has directly focused on bareback versus with condoms and ignored other possible messaging received from SEM. For example, if young GBM are looking to SEM for education on sexual behaviors, in addition to viewing bareback SEM as normative, they may also be acquiring messaging about how and where to meet sexual partners and expectations for interactions. Aggression in SEM, for example, is an area that has been highly researched for heterosexual, but not for GBM.

Limitations

The sample for this study was diverse in terms of age, income, and geographical location; however the sample is comprised of mainly HIV-negative well-educated White men and thus may not be generalizable to all GBM. The data used in these analyses comes from cross-sectional data and there is not sufficient evidence to suggest that these associations between viewing large percentages of bareback SEM and engaging in CAS are stable overtime or that discontinuing the viewing of bareback SEM will change behavioral outcomes. Although the data presented suggests that viewing bareback SEM is associated with CAS behavior, it is not possible at this time to determine if the participants are viewing SEM containing bareback anal sex because they already engage in CAS or if viewing SEM containing bareback sex is leading them to normalize CAS and thus engage in it more freely. These data are self-reported and therefor subject to social desirability bias, such that some GBM may under report both sexual acts and SEM viewing frequencies and contents.

Furthermore, because our data are cross-sectional, we cannot suggest causation between viewing bareback SEM and engaging in CAS. However, this potential causal relationship has been shown with some success by other researchers. One such study asked participants a variety of questions about their thoughts around if the type of SEM they viewed influenced there sexual behaviors.19 These researchers reported that the majority of their participants believed that SEM contributed to other GBMSM engaging in sexual risk, and fewer, about half, reported believing SEM contributed to their own engagement in sexual risk. Another study examined safe-sex intentions after viewing either SEM that depicted anal sex with condoms versus SEM depicting anal sex without condoms.32 These researchers reported that those who watched SEM depicted bareback behaviors rated significantly lower on scales measuring safe-sex intentions.

Lastly, we addressed percentage of bareback SEM consumption with the question “How would you describe the porn you watched in the last 3 months?” Responses were provided via a sliding scale ranging from “0% - all condoms” to “100% - all bareback.” The wording for this measure may be misleading to come participants as we were aiming to address what percentage of SEM containing anal sex (both with and without condoms) our participants viewed. The question is not entirely clear that we are asking only about anal sex and not taking into consideration SEM that doesn't contain anal sex (i.e. masturbation or oral). We do not think this measurement error changes our findings; however we do recommend that future studies aiming to examine these associations use a clearer measure to capture this construct. Additionally, this measurement error highlights the need for more standardized measures to be used across studies when examining GBM and SEM consumption.

Conclusions

These findings expand on past research and suggest that there is a connection between SEM and sexual risk such that higher percentages of bareback SEM consumed is linked to CAS among a variety of GBM across the United States regardless of age, race, education, and geographical location. Given these findings, it is important for more research to be conducted on exactly how GBM learn about HIV prevention techniques and call for more focus on behavioral outcomes and other messages that GBM may be learning from media, specifically SEM.

Acknowledgments

One Thousand Strong study was funded by a research grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; Jeffrey T. Parsons & Christian Grov, MPIs). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a Career Development Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01-DA039030; H. Jonathon Rendina, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the other members of the One Thousand Strong Study Team (Ana Ventuneac, Demetria Cain, Mark Pawson, Ruben Jimenez, Chloe Mirzayi, Brett Millar, Raymond Moody, and Steve John) and other staff from the Center for HIV/AIDS Educational Studies and Training (Chris Hietikko, Andrew Cortopassi, Brian Salfas, Doug Keeler, Chris Murphy, Carlos Ponton, and Paula Bertone). We would also like to thank the staff at Community Marketing Inc. (David Paisley, Heather Torch, and Thomas Roth). Finally, we thank Jeffrey Schulden at NIDA, the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript, and all of our participants in the One Thousand Strong study.

Funding: Funding support was provided by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA036466; PIs: Parsons & Grov). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported by a National Institute on Drug Abuse Career Development Award (K01-DA039030).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.CDC. Basic Statistics - New HIV Diagnoses by Transmission Category. 2015. 2016 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html.

- 2.CDC. Estimated HIV Incidence in the United States, 2007–2010. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. [Accessed 8/12/16, 2016]. HIV Surveillance – Epidemiology of HIV Infection (through 2013) http://www.cdc.gov/HIV/library/slidesets/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison TG, Morrison MA, Bradley BA. Correlates of gay men's self-reported exposure to pornography. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2007;19(2):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosser BS, Grey JA, Wilkerson JM, et al. A commentary on the role of sexually explicit media (SEM) in the transmission and prevention of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1373–1381. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0135-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbenick D, Reece M, Schick V, Sanders SA, Dodge B, Fortenberry JD. Sexual behavior in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. The journal of sexual medicine. 2010;7(s5):255–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell D, Johnson C, Lansky A, et al. Calculating HIV and syphilis rates for risk groups: estimating the national population size of men who have sex with men. Paper presented at: National STD Prevention Conference 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downing MJ, Schrimshaw EW, Scheinmann R, Antebi-Gruszka N, Hirshfield S. Sexually explicit media use by sexual identity: A comparative analysis of gay, bisexual, and heterosexual men in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0837-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hald GM, Malamuth NM. Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(4):614–625. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper S, Rosser BS, Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, Danilenko G. An online needs assessment of a virtual community: what men who use the internet to seek sex with men want in Internet-based HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(6):867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9373-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Træen B, Nilsen TSr, Stigum H. Use of pornography in traditional media and on the Internet in Norway. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43(3):245–254. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCormack M, Wignall L. Enjoyment, exploration and education: Understanding the consumption of pornography among young men with non-exclusive sexual orientations. Sociology. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0038038516629909. 0038038516629909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hald GM, Smolenski D, Rosser B. Perceived effects of sexually explicit media among men who have sex with men and psychometric properties of the Pornography Consumption Effects Scale (PCES) The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(3):757–767. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02988.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubicek K, Carpineto J, McDavitt B, Weiss G, Kipke MD. Use and perceptions of the internet for sexual information and partners: a study of young men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(4):803–816. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. In the dark: Young men's stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37(2):243–263. doi: 10.1177/1090198109339993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Downing MJ, Schrimshaw EW, Antebi N, Siegel K. Sexually explicit media on the Internet: A content analysis of sexual behaviors, risk, and media characteristics in gay male adult videos. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(4):811–821. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.STR8UpGayPorn.com. [Accessed 8/12/16, 2016];Bareback Gay Porn Studios Overwhelmingly Outnumber Condom Gay Porn Studios. 2016 http://str8upgayporn.com/bareback-gay-porn-vs-condom-gay-porn/

- 18.Eaton LA, Cain DN, Pope H, Garcia J, Cherry C. The relationship between pornography use and sexual behaviours among at-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men. Sexual health. 2012;9(2):166–170. doi: 10.1071/SH10092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrimshaw EW, Antebi-Gruszka N, Downing MJ., Jr Viewing of Internet-Based Sexually Explicit Media as a Risk Factor for Condomless Anal Sex among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Four US Cities. PloS one. 2016;11(4):e0154439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein D, Silvera R, Hagerty R, Marmor M. Viewing pornography depicting unprotected anal intercourse: Are there implications for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men? Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(2):411–419. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9789-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nelson KM, Simoni JM, Morrison DM, et al. Sexually explicit online media and sexual risk among men who have sex with men in the United States. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(4):833–843. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosser BS, Smolenski DJ, Erickson D, et al. The effects of gay sexually explicit media on the HIV risk behavior of men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1488–1498. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Træen B, Hald GM, Noor SW, Iantaffi A, Grey J, Rosser BS. The relationship between use of sexually explicit media and sexual risk behavior in men who have sex with men: exploring the mediating effects of sexual self-esteem and condom use self-efficacy. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2014;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2013.823900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory. 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skinner BF. Operant behavior. American Psychologist. 1963;18(8):503. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grov C, Cain D, Whitfield TH, et al. Recruiting a US National Sample of HIV-Negative Gay and Bisexual Men to Complete at-Home Self-Administered HIV/STI Testing and Surveys: Challenges and Opportunities. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2015:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s13178-015-0212-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Whitfield TH, Grov C. Familiarity with and Preferences for Oral and Long-Acting Injectable HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) in a National Sample of Gay and Bisexual Men in the US. AIDS and Behavior. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1370-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grov C, Cain D, Rendina HJ, Ventuneac A, Parsons JT. Characteristics Associated With Urethral and Rectal Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Diagnoses in a US National Sample of Gay and Bisexual Men: Results From the One Thousand Strong Panel. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(3):165–171. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon SR, Sawilowsky SS. Impact of rank-based normalizing transformations on the accuracy of test scores. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. 2009;8(2):448–462. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agresti A, Kateri M. International encyclopedia of statistical science. Springer; 2011. Categorical data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkerson JM, Iantaffi A, Smolenski DJ, Horvath KJ, Rosser BS. Acceptability of HIV-prevention messages in sexually explicit media viewed by men who have sex with men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2013;25(4):315–326. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.4.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jonas KJ, Hawk ST, Vastenburg D, de Groot P. “Bareback” pornography consumption and safe-sex intentions of men having sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2014;43(4):745–753. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]