Abstract

Objective

Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from largely non-Hispanic White cohorts suggests that positive psychosocial factors, particularly self-efficacy and social support, may protect against late-life cognitive decline. Identifying potentially protective factors in racial/ethnic minority elders is of high importance due to their increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The overall goal of this study was to characterize cross-sectional associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognitive domains among Black, Hispanic, and White older adults.

Method

548 older adults (41% Black, 28% Hispanic, 31% White) in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project completed cognitive and psychosocial measures from the NIH Toolbox and standard neuropsychological tests. Multiple-group regressions were used to compare cross-sectional associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition across racial/ethnic groups, independent of demographics, depressive symptoms, and physical health.

Results

Positive associations between self-efficacy and language did not significantly differ across race/ethnicity, although the bivariate association between self-efficacy and language was not significant among Hispanics. Additional positive associations were observed for Whites and Blacks, but not Hispanics. Negative associations between emotional support and purpose in life and working memory were seen only in Hispanics.

Conclusions

Results confirm and extend the link between self-efficacy and cognition in late life, particularly for White and Black older adults. Previous studies on positive psychosocial factors in cognitive aging may not be generalizable to Hispanics. Longitudinal follow-up is needed to determine whether negative relationships between certain psychosocial factors and cognition in Hispanics reflect reverse causation, threshold effects, and/or negative aspects of having a strong social network.

Keywords: Social Support, Self-Efficacy, Working Memory, Language, Executive Function, African American, Hispanic

Introduction

Evidence from multiple cohort studies of older adults suggests that positive psychosocial factors (i.e., self-efficacy, social support, well-being) may protect against late-life cognitive decline independent of negative affect. For example, social participation predicted less subsequent decline in perceptual speed, but not vice versa, in the Berlin Aging Study (Lövdén, Ghisletta & Lindenberger, 2005). Both social support and self-efficacy beliefs at baseline predicted better subsequent cognitive performance among participants in the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging (Seeman et al., 1996; Seeman et al., 2001). In a previous cross-sectional study using a national sample of older adults, we confirmed the conceptual distinctness of positive psychosocial factors from negative affect (i.e., depression, anxiety, anger) and found that self-efficacy and social support were most strongly associated with cognition independent of other positive and negative psychosocial factors and physical health (Zahodne, Nowinski, Gershon, & Manly, 2014a).

Because all of the studies reviewed above were conducted in largely non-Hispanic White populations, it is not known whether positive psychosocial factors are differentially protective across racial/ethnic groups. Identifying potentially protective factors in racial/ethnic minority elders is of high importance because Blacks and Hispanics are three to four times more likely to develop incident Alzheimer’s disease than Whites (Tang et al., 2001). In addition, the elderly population in the U.S. is becoming increasingly racially/ethnically diverse (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). For example, it is projected that more than one quarter of the U.S. elderly population will be Hispanic in 2050 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004).

Associations between psychosocial factors and cognition may be even stronger in racial/ethnic minority older adults. According to the differential vulnerability hypothesis, members of socially disadvantaged groups may lack certain resources (e.g., high-quality education) that could buffer against the negative impacts of low self-efficacy or low social support (Aday, 2001). Indeed, we have previously found that other psychosocial factors (i.e., depressive symptoms, external locus of control) are more strongly related to cognitive outcomes among Black older adults than White older adults (Zahodne et al., 2015; Zahodne, Nowinski, Gershon, & Manly, 2014a). These findings are in line with the reserve capacity model, which states that individuals with lower social status are more likely to encounter negative life events (e.g., discrimination, exposure to trauma, daily hassles) that could interact synergistically with other risk factors (Gallo & Matthews, 2003). Racial/ethnic variation in the absolute levels of both psychosocial factors (Taylor, Chatters, Toler Woodward, Brown, 2013) and cognitive functioning (Díaz-Venegas, Downer, Langa, & Wong, 2016) may also influence the strength of associations between constructs.

The overall goal of this study was to characterize cross-sectional associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognitive domains, independent of demographics, depressive symptoms and physical health, among Black, Hispanic, and White older adults. The specific aims were to test whether associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition are significantly different across Blacks and Whites, Hispanics and Whites, or Blacks and Hispanics. Based on our previous study (Zahodne, Nowinski, Gershon, & Manly, 2014a), we predicted that self-efficacy and emotional support would be most strongly associated with cognition. In addition, we predicted that associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition would be stronger in racial/ethnic minority groups based on the hypothesis of differential vulnerability. Due to the lack of prior work on racial/ethnic differences in associations between specific positive psychosocial factors and cognition in late life, we did not have specific predictions about which specific associations would be most likely to differ across racial/ethnic groups.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The 548 individuals in this sample were participants in the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP; Tang et al., 2001; Manly et al., 2005). WHICAP is a prospective, community-based, longitudinal study of aging and dementia in northern Manhattan. In brief, adults aged 65 and older living in the geographic area of northern Manhattan were identified from Medicare records or a commercial marketing company in three waves: 1992, 1999, and 2009. The current sample included only participants recruited in the newest (2009) wave who participated in a recent ancillary study of psychosocial functioning. Exclusion criteria for the current, cross-sectional study were: (1) a diagnosis of dementia according to DSM-III criteria via a consensus group of neurologists, psychiatrists and neuropsychologists (N = 4), (2) self-reported race/ethnicity other than Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, or White (N = 4), and missing data (N = 22). Race and ethnicity were determined via self-report using the format of the 2000 U.S. Census. In this study, Blacks and Whites were all non-Hispanic, and Hispanics could have identified as any race. Characteristics of the final analytic sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics and comparisons across racial/ethnic groups

| Whole group (N=548) | Black (N=225) | Hispanic (N=153) | White (N=170) | Group differences† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 74.6 (6.2) | 74.4 (6.4) | 75.7 (6.1) | 74.0 (6.0) | B=W<H |

| Female (%) | 62.6 | 67.1 | 64.7 | 54.7 | W=H=B; W<B |

| Education (years) | 13.2 (4.5) | 13.8 (2.9) | 9.0 (4.6) | 16.0 (3.1) | H<B<W |

| Income category (1–12) | 8.1 (2.7) | 8.0 (2.6) | 5.9 (2.7) | 10.4 (2.2) | H<B<W |

| Test language (% Spanish) | 23.4 | 0.0 | 83.7 | 0.0 | B=W<H |

| Health | |||||

| Hypertension (%) | 61.1 | 71.6 | 64.7 | 44.1 | W<H=B |

| Diabetes (%) | 24.8 | 28.9 | 34.0 | 11.2 | W<B=H |

| Heart disease (%) | 17.0 | 17.8 | 16.2 | 16.5 | H=W=B |

| Stroke (%) | 2.4 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 1.8 | H=W=B |

| Sadness (theta) | −0.3 | −0.2 (0.8) | −0.6 (0.9) | −0.1 (0.4) | H<B=W |

| Cognition | |||||

| Episodic memory (z-score composite) | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.5 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.6) | H=B<W |

| Language (z-score composite) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.4) | H<B<W |

| Visuospatial (z-score composite) | 0.7 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 1.0 (0.3) | H<B<W |

| Dimensional Change Card Sort (standard score) | 93.6 (10.7) | 92.8 (8.6) | 88.1 (7.0) | 99.6 (8.5) | H<B<W |

| Flanker (standard score) | 93.0 (8.2) | 92.5 (7.0) | 87.6 (5.8) | 98.4 (8.2) | H<B<W |

| List Sorting (standard score) | 93.7 (10.7) | 93.5 (9.1) | 86.1 (9.6) | 100.6 (8.9) | H<B<W |

| Pattern Comparison (standard score) | 83.3 (13.8) | 83.6 (13.1) | 74.8 (12.8) | 91.0 (10.5) | H<B<W |

| Psychosocial | |||||

| Self-Efficacy (theta) | 0.0 (1.20) | −0.0 (1.0) | −0.1 (1.1) | 0.1 (0.9) | H=B=W |

| Emotional Support (theta) | −0.3 (1.0) | −0.5 (1.0) | 0.0 (1.1) | −0.3 (0.9) | B=W<H |

| Friendship (theta) | 0.0 (1.1) | 0.0 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.2) | −0.2 (1.0) | B=W<H |

| Instrumental Support (theta) | −0.2 (1.1) | −0.4 (1.1) | 0.1 (1.2) | −0.4 (1.1) | B=W<H |

| Loneliness (theta) | 0.0 (1.0) | −0.0 (1.0) | −0.3 (1.1) | 0.2 (0.9) | H<B=W |

| Meaning & Purpose (theta) | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.2 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.9) | −0.0 (1.0) | W<B=H |

| Positive Affect (theta) | −0.2 (0.9) | −0.1 (1.0) | −0.3 (1.0) | −0.3 (0.8) | H=W=B |

| Life Satisfaction (theta) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.9) | 0.4 (0.9) | B<W=H |

Racial/ethnic group differences summarize the results of inferential tests (i.e., analysis of variance with Bonferroni-corrected post hoc comparisons for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables) with a p-value of 0.05.

WHICAP participants are followed up at 18–24 month intervals with a battery of cognitive, functional, and health measures administered in the participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish) by bilingual research staff. The current, cross-sectional study analyzed data from a study visit that occurred between 2013 and 2016. This study complied with the ethical rules for human experimentation that are stated in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cognitive Outcomes

Cognitive functioning was assessed with a comprehensive neuropsychological battery as previously described (Stern et al., 1992). Back translation and reconciliation were used to ensure comparability of English and Spanish measures. Using factor analysis, Siedlecki et al. (2010) summarized the WHICAP neuropsychological battery into cognitive domains that, importantly, were found to be invariant across English and Spanish speakers. Based on this factor analysis, composite scores were derived for the overall WHICAP sample by converting all cognitive variables to z-scores and averaging them within each cognitive domain. Episodic memory composite scores include immediate, delayed, and recognition trials from the Selective Reminding Test (Buschke & Fuld, 1974). Language scores include measures of naming, letter and category fluency, verbal abstract reasoning, repetition, and comprehension. Visuospatial scores include recognition and matching trials from the Benton Visual Retention Test (Benton, 1955), the Rosen Drawing Test (Rosen, 1981), and the Identities and Oddities subtest of the Dementia Rating Scale (Mattis, 1976).

Cognitive functioning was further assessed with computerized tests from the NIH Toolbox Cognition module (Weintraub et al., 2013). Spanish versions of these measures were developed using a modified version of the FACIT translation method (Eremenco, Cella & Arnold, 2005; Bonomi et al., 1996), which involves forward and back translation, review by a bilingual expert, and harmonization (Casaletto et al., 2016). To complement the WHICAP neuropsychological battery, we administered NIH Toolbox tests of executive functioning (Flanker Inhibitory Control & Attention, Dimensional Change Card Sort), working memory (List Sorting), and processing speed (Pattern Comparison). Unadjusted standard scores were used in the current study. These scores were derived from the overall, nationally representative NIH Toolbox normative sample (i.e., community-dwelling individuals aged 3–85) regardless of age, language, or other characteristic. Thus, these scores do not explicitly correct for any demographic variables. Comprehensive data on the psychometric properties of these tests is available from a national sample of English and Spanish speakers (Weintraub et al., 2013). In brief, test-retest reliability of each test is satisfactory, with reported intraclass correlation coefficients between 0.72 (Pattern Comparison) and 0.94 (Flanker) in adults. Convergent validity for each test was supported by significant, moderately-sized correlations with gold-standard measures, ranging from 0.48 (Flanker) to 0.58 (List Sorting).

Psychosocial Predictors

Psychosocial functioning was assessed with the NIH Toolbox Emotion module, which comprises Likert-type items presented using computerized adaptive testing based on item response theory (Salsman et al., 2013). These items were completed on a computer by the participant, under the supervision of a trained administrator. Spanish versions of these items, item context(s), and answer options were translated using the FACIT translation methodology (Eremenco, Cella & Arnold, 2005; Bonomi et al., 1996).

The current study focused on positive psychosocial factors assessed by the NIH Toolbox: self-efficacy (Self-Efficacy survey), social relationships (i.e., Emotional Support, Friendship, Instrumental Support, and Loneliness surveys), and well-being (i.e., Life Satisfaction, Meaning & Purpose, and Positive Affect surveys). Reliability (Cronbach α) for surveys included in the present study has been reported to range from 0.89 (Meaning & Purpose) to 0.97 (Sadness and Emotional Support), and convergent validity (absolute values of associations with gold-standard measures) ranges from 0.64 (Meaning & Purpose) to 0.92 (Positive Affect) in adults (Salsman et al., 2013). Unadjusted scores on the NIH Toolbox Emotion surveys are reported as theta scores, which reflect the standardized latent trait values centered on a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1. Higher theta scores correspond to higher levels of the underlying trait.

Covariates

Models controlled for age, sex, years of education, language of test administration, depressive symptoms, and health status. Supplementary Table 1 shows bivariate associations between the selected covariates and the variables of interest. Sex and education (0–20 years) were measured via self-report. Depressive symptoms were quantified as continuous score on the NIH Toolbox Sadness survey. Health status was indexed by four dichotomous variables corresponding to the self-reported presence/absence of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke.

In a subsample of participants with available data, supplementary models examined the role of income, acculturation, and school quality. Monthly household income (1–12) was self-reported using the following 12 categories: $450 or less, $451–$550, $551–$650, $651–$750, $751–$1,000, $1,001–$1,250, $1,251–$1,500, $1,501–$1,750, $1,751–$2,000, $2,001–$3,000, $3,001–$4,000, and more than $4,000. Among Spanish speaking participants, acculturation was indexed by self-rated English language proficiency on a four-point scale from “Not at all” to “Very well” in response to the question, “How well do you speak English?” Among Spanish speakers, school quality was indexed by the Word Accentuation Test (WAT; Del Ser, González-Montalvo, Martínez-Espinosa, Delgado-Villapalos, & Bermejo, 1997), a Spanish reading measure.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were computed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Group differences were described using analyses of variance (ANOVAs) and Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. Regression analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA). Multiple-group regression was used to compare associations between the positive psychosocial factors and cognition across racial/ethnic groups. Separate models were run for each cognitive outcome, and separate models were run comparing each pair of racial/ethnic groups (Black versus White, Hispanic versus White, Black versus Hispanic). In the multiple-group models, all parameters were estimated separately in two groups (e.g., Black and White). Initially, all regression paths (including those involving covariates) were forced to equivalence across groups (fixed model). Note that intercepts and residual variances were not forced to equivalence in any models (fixed or free). Next, a specific parameter of interest (e.g., the regression path between self-efficacy and the cognitive outcome) was freely estimated across groups (free model). Regression paths involving each psychosocial variable were freed one at a time. A chi-square difference between the fixed and free models in excess of its critical value was interpreted as evidence for a significant difference in the association across groups. Because separate models were run for each of the seven cognitive outcomes, alpha was set at 0.007 (0.05/7). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine whether results differed upon exclusion of the 13 participants who reported a history of stroke and upon omission of depressive symptom and health status covariates.

Results

Level Differences Across Racial/Ethnic Groups

Table 1 displays cognitive, psychosocial, and covariate data separately for the three racial/ethnic groups. In analyses that did not control for any covariates, racial/ethnic disparities were evident for all seven cognitive outcomes. Specifically, Whites obtained higher scores than both Blacks and Hispanics. Blacks obtained higher scores than Hispanics on all cognitive outcomes except the episodic memory composite.

In bivariate comparisons, there were also significant racial/ethnic differences in psychosocial functioning. Specifically, Hispanics reported more social support than Whites and Blacks, as evidenced by higher scores on Emotional Support, Friendship and Instrumental Support surveys, as well as lower scores on the Loneliness survey. Both Hispanics and Blacks reported more purpose in life than Whites. Finally, Whites and Hispanics reported greater life satisfaction than Blacks. There were no racial/ethnic group differences in self-reported self-efficacy or positive affect.

With regard to covariates, the Hispanic group was slightly older than Black and White groups, and there were significantly more Black women than White women. Whites reported the highest level of education, followed by Blacks, and then Hispanics. Blacks and Hispanics were more likely to report hypertension and diabetes than Whites, but there were no significant group differences in self-reported heart disease or stroke. Blacks and Whites reported more depressive symptoms than Hispanics. In a subset of 505 participants with available data on income, Whites reported the highest income, followed by Blacks, and then Hispanics.

Multiple Group Models

Table 2 presents results from multiple-group models comparing associations between the positive psychosocial factors and cognition across the three racial/ethnic groups. As shown, there were no significant differences in the associations between any positive psychosocial factors and cognition across Blacks and Whites. In models conducted within those groups, higher self-efficacy was associated with better language ability (beta = 0.24, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001). This association did not significantly differ across Hispanics and Whites, or across Hispanics and Blacks.

Table 2.

Results (chi square differences) of multiple-group models testing differential associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition across race/ethnicity

| Memory | Language | Visuospatial | DCCS | Flanker | List Sorting | Pattern Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black versus White | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Self-Efficacy | −0.123 | −2.242 | 0.000 | −0.062 | −0.137 | −0.371 | −1.604 |

| Emotional Support | −1.262 | −3.134 | −0.759 | −2.725 | −0.220 | −0.038 | −1.711 |

| Friendship | −0.015 | −0.049 | −0.043 | −0.780 | −0.017 | −2.380 | −0.791 |

| Instrumental Support | −0.008 | −1.235 | −3.186 | −1.109 | −0.375 | −0.007 | −0.018 |

| Loneliness | −2.529 | −0.101 | −0.028 | −0.196 | −0.001 | −0.964 | −0.194 |

| Meaning & Purpose | −1.393 | 0.000 | −0.653 | −3.643 | −2.746 | −3.595 | −0.005 |

| Positive Affect | −0.948 | −2.025 | −0.342 | −0.008 | −0.093 | 0.000 | −0.662 |

| Life Satisfaction | −1.545 | −0.380 | −0.325 | −0.299 | −1.371 | −0.007 | −0.867 |

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic versus White | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Self-Efficacy | −0.922 | −0.357 | −1.526 | −0.044 | −2.684 | −1.964 | −0.927 |

| Emotional Support | −0.024 | −6.278 | −6.063 | −5.217 | −0.861 | −9.052* | −2.948 |

| Friendship | −0.047 | −1.543 | −2.387 | −2.756 | −0.055 | −8.838* | −1.074 |

| Instrumental Support | −0.168 | −1.211 | −1.941 | −1.495 | −2.459 | −1.328 | −0.878 |

| Loneliness | −0.224 | −0.075 | −2.115 | −1.207 | −2.524 | −2.949 | −3.052 |

| Meaning & Purpose | 0.000 | −1.003 | −1.832 | −3.540 | −7.211 | −7.641* | −2.102 |

| Positive Affect | −0.752 | −1.312 | −0.908 | −0.005 | −2.084 | −0.027 | −1.607 |

| Life Satisfaction | −0.527 | −0.016 | −0.555 | −0.953 | −3.645 | −0.003 | −0.851 |

|

| |||||||

| Black versus Hispanic | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Self-Efficacy | −1.665 | −4.388 | −0.176 | −0.401 | −7.297* | −5.460 | −5.301 |

| Emotional Support | −0.748 | −0.493 | −2.460 | −0.027 | −0.911 | −7.817* | −0.330 |

| Friendship | −0.731 | −0.837 | −1.995 | −0.017 | −0.276 | −1.990 | −0.045 |

| Instrumental Support | −0.501 | −0.085 | −0.056 | −0.037 | −2.104 | −2.262 | −1.903 |

| Loneliness | −0.147 | −0.005 | −0.531 | −0.002 | −4.067 | −0.564 | −1.952 |

| Meaning & Purpose | −0.774 | −0.277 | −0.001 | −0.893 | −1.353 | −1.562 | −1.370 |

| Positive Affect | −0.035 | −0.547 | −0.121 | −0.441 | −1.978 | −0.014 | −0.310 |

| Life Satisfaction | −3.872 | −0.740 | −0.008 | −0.027 | −0.147 | −0.001 | −0.055 |

p < 0.007 based on chi square test with 1 degree of freedom

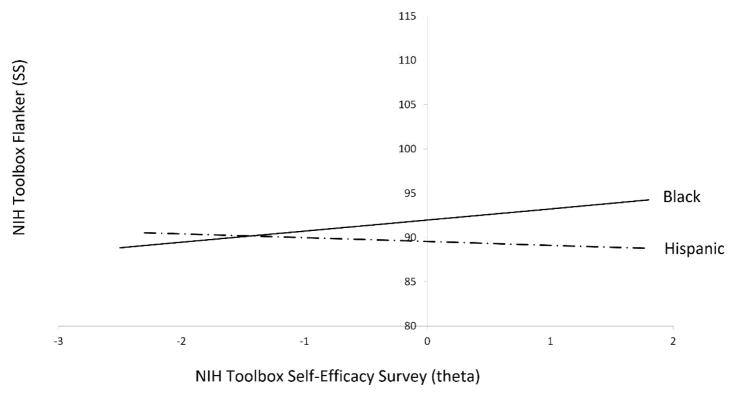

In contrast, model fit was significantly improved when the association between self-efficacy and attention/inhibition (i.e., NIH Toolbox Flanker) was allowed to differ across Hispanics and Blacks. As shown in Figure 1, higher self-efficacy was associated with better attention/inhibition in Blacks (beta = 0.18, SE = 0.07, p = 0.01), but not in Hispanics (beta = −0.08, SE = 0.09, p = 0.35). The association between self-efficacy and attention/inhibition did not differ across Blacks and Whites, or across Hispanics and Whites.

Figure 1.

Association between self-efficacy and attention/inhibition that significantly differed across Blacks and Hispanics. Depicted results are set at the following covariate values: age 75, male sex, 12 years of education, NIH Toolbox Sadness survey theta = 0, absence of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. SS=Standard Score.

Model fit was also significantly improved when associations between emotional support and working memory (i.e., NIH Toolbox List Sorting) were allowed to differ across Hispanics and Whites, and across Hispanics and Blacks. As shown in Figure 2, greater emotional support was associated with worse working memory in Hispanics (beta = −0.24, SE = 0.10, p = 0.02), but not in Blacks (beta = 0.13, SE = 0.08, p = 0.11) or Whites (beta = 0.09, SE = 0.09, p = 0.32).

Figure 2.

Association between emotional support and working memory that significantly differed across Blacks, Hispanics and Whites. Depicted results are set at the following covariate values: age 75, male sex, 12 years of education, NIH Toolbox Sadness survey theta = 0, absence of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. SS=Standard Score.

Model fit was also significantly improved when the association between friendship and working memory (i.e., NIH Toolbox List Sorting) was allowed to differ across Hispanics and Whites only. As shown in Figure 3, greater friendship was associated with better working memory in Whites (beta = 0.22, SE = 0.09, p = 0.008), but not Hispanics (beta = −0.08, SE = 0.10, p = 0.43). The association between friendship and working memory did not differ across Hispanics and Blacks, or across Whites and Blacks.

Figure 3.

Association between friendship and working memory that significantly differed across Hispanics and Whites. Depicted results are set at the following covariate values: age 75, male sex, 12 years of education, NIH Toolbox Sadness survey theta = 0, absence of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. SS=Standard Score.

Model fit was also significantly improved when the association between purpose in life and List Sorting was allowed to differ across Hispanics and Whites only. As shown in Figure 4, higher purpose in life was associated with worse working memory in Hispanics (beta = −0.24, SE = 0.09, p = 0.008), but not in Whites (beta = 0.05, SE = 0.09, p = 0.57). The association between purpose in life and working memory did not differ across Hispanics and Blacks, or across Whites and Blacks.

Figure 4.

Association between purpose in life and working memory that significantly differed across Hispanics and Whites. Depicted results are set at the following covariate values: age 75, male sex, 12 years of education, NIH Toolbox Sadness survey theta = 0, absence of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke. SS=Standard Score.

Supplementary models examined the potential role of income, acculturation, and school quality in explaining significant findings that were unique to the Hispanic group. Because our proxies for acculturation and school quality were English language proficiency and Spanish reading level, respectively, these additional analyses were conducted in a subset of 95 Hispanics tested in Spanish who had available data. Compared to Hispanics who chose to be tested in English, Hispanics who chose to be tested in Spanish were significantly older and reported less education, less income, fewer depressive symptoms, and more hypertension. Due to the small sample size, these supplementary models only included covariates found to be statistically significant in primary models (i.e., age, education, stroke). In initial models, neither emotional support (beta = −0.06, p = 0.78) nor purpose in life (beta = 0.06, p = 0.74) was significantly associated with List Sorting among English-speaking Hispanics, though it should be noted these analyses included only 23 individuals. In initial models, both emotional support (beta = −0.28, p = 0.002) and purpose in life (beta = −0.26, p = 0.005) were associated with lower scores on List Sorting among Spanish speaking-Hispanics. In models that included income, acculturation and school quality, these associations remained largely unchanged for both emotional support (beta = −0.25, p = 0.008) and purpose in life (beta = −0.26, p = 0.006) for Spanish-speaking Hispanics. Income, acculturation, and school quality were not significantly associated with working memory (all p’s > .143).

Sensitivity analyses revealed that this pattern of results was largely unchanged after individuals who reported a history of stroke were excluded. Additional analyses were conducted to investigate the possibility that associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition were being masked by the inclusion of one or more of the covariates that could be mediating an association. Specifically, models were re-run, excluding the depressive symptoms and health status covariates, and results were unchanged.

Discussion

The results of this study extend previous findings on the links between positive psychosocial factors and cognition in older adults. In a larger and much more racially/ethnically diverse sample, we found that self-efficacy and social support are positively related to cognition in late life, independent of other positive psychosocial factors, depressive symptoms and physical health (Zahodne, Nowinski, Gershon & Manly, 2014a). While positive associations between self-efficacy and language did not significantly differ across Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites in this study, bivariate associations between self-efficacy and language were not significant in the Hispanic group. Therefore, lack of significant differences in the magnitude of association between self-efficacy and language do not provide strong support for the generalizability of potential interventions designed to enhance self-efficacy and improve cognitive performance in Hispanic older adults. Because self-efficacy was additionally associated with better attention/inhibition in Blacks, more widespread cognitive effects in this group may be possible if self-efficacy interventions are found to be effective.

While the positive associations between self-efficacy and cognition identified in the present study were cross-sectional, they could reflect a positive influence of self-efficacy on cognitive abilities. For example, efficacy beliefs may buffer physiologic responses to stress and threat that can erode cognitive and neural efficiency (Wright & Dismukes, 1995). According to the theory of self-efficacy articulated by Bandura (1989), self-efficacy beliefs can also improve cognition via cognitive, affective, or motivational pathways. Confidence in one’s abilities may enhance motivation and attention during effortful tasks, both in a testing setting and in daily life. Indeed, reporting higher self-efficacy predicts greater benefit from cognitive training (Carretti et al., 2011). Conversely, reporting more external locus of control predicts less benefit from cognitive training (Zahodne et al., 2015). Together, these results suggest that self-efficacy may not only foster better cognitive performance in the moment, but also increase motivation to learn strategies, resulting in further improvements in cognition over the long term. An alternative explanation for cross-sectional associations between self-efficacy and cognition is that possessing better cognitive skills may enhance one’s feelings of self-efficacy. Conversely, cognitive limitations may reduce one’s experience of success, thereby reducing self-efficacy beliefs. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, and longitudinal work has documented bi-directional associations between self-efficacy beliefs and cognition in late life (Seeman et al., 1996).

With regard to social support, multiple-group modeling revealed conflicting results in Hispanics, compared to both Whites and Blacks. For example, the association between friendship and working memory was positive in Whites but nonsignificant in Hispanics. This result for the White group is consistent with the majority of previous studies showing a positive association between social variables and cognition, which did not include substantial proportions of Hispanics (Seeman, Lusignolo, Albert & Berkman, 2001; Barnes, Mendes de Leon, Wilson, Bienias, & Evans, 2004; Kats et al., 2016; Ellwardt, Aartsen, Deeg, & Steverink, 2013; Pillemer & Holtzer 2016). The current results suggest that findings such as these may not be generalizable to Hispanics. Among Whites in this study, only the association involving friendship reached statistical significance, which is consistent with several studies suggesting that social support from non-kin is more influential in cognitive aging than social support from kin, perhaps because the former is discretionary, whereas the latter is more often compulsory and characterized by both positive and negative interactions (Giles 2012; Glei, Landau, Goldman, 2005).

In contrast to our previous study of mostly non-Hispanic White older adults (Zahodne, Nowinski, Gershon, & Manly, 2014a), emotional support was not associated with better cognition in this racially/ethnically diverse sample. The association between emotional support and working memory was negative in Hispanics, but nonsignificant in both Whites and Blacks. Interpretations of this negative association among Hispanics must take into account that this group exhibited lower cognitive performance, reported more social support (across all four social support surveys), and had lower socioeconomic status (SES; as indexed by both educational attainment and income) than both Blacks and Whites in this study. Thus, one potential explanation is reverse causation: Hispanics in this study may have been experiencing a mobilization of their social networks in response to early signs of cognitive impairment. This phenomenon may not have been present in Whites or Blacks because these groups were less likely to be experiencing early cognitive impairment, as evidenced by their higher cognitive scores. Longitudinal studies are needed to explore the possibility of reverse causation.

Another potential explanation is that the social support-health relationship is non-linear: social support may be beneficial up to a point, but excessive support may be harmful. Indeed, observational and experimental studies show that excessive support can lead to psychological distress, perhaps by eroding feelings of self-efficacy and inducing feelings of dependency (Bolger & Amarel, 2007; Silverstein, Chen & Heller, 1996). While social support-cognition associations reported in this study were independent of self-efficacy and depressive symptoms, it is possible that excessive support could be negatively influencing cognition through other mechanisms (e.g., perceived constraints).

Many studies have attributed the finding that Hispanics often exhibit better health outcomes than expected (i.e., the Hispanic Paradox) to social resources related to Hispanic cultural values such as allocentrism, familism and simpatía (Marin & Marin, 1991). However, these values may also negatively influence health by lowering willingness to adopt positive behavioral and health changes that do not directly benefit family members, discouraging disclosure of information that could compromise personal respect, or preventing proactive engagement with the medical system (Marin & Marin, 1991; Gallo, Panedo, Espinosa de los Monteros, & Arguelles, 2009). While the current study controlled for self-reported presence/absence of several health conditions, these variables likely fail to capture the full variance in health present in the sample.

In the context of low SES, members of a strong social network may be burdened by providing material resources to network members, which may outweigh any health benefits of perceived emotional support. Indeed, there is some evidence that social support is less health protective within low-SES groups (Melchior, Berkman, Zunzunegui, Niedhammer, Chea, Goldberg, 2003). While the negative association between emotional support and working memory in Hispanics persisted after controlling for joint household income, Hispanics in this study reported a restricted range of income. Future work is needed to further investigate the causes and consequences of the negative emotional support-cognition association in Hispanics. Specifically, studies should include precise measures of potential mediators such as perceived constraints, subjective financial status, and lifestyle factors. Given that the NIH Toolbox Emotion Module is a relatively new, research-based measure that was not specifically developed for racial/ethnic minorities, it is also possible that the Emotional Support survey does not have high construct validity in older Hispanics. Of note, the adult calibration and validation sample for the NIH Toolbox Emotion Module was 90% non-Hispanic, and most of the included Hispanic adults were under age 65. Further research is needed to explore the construct validity of NIH Toolbox measures in older Hispanics. Further exploration in Blacks is also warranted, given that the adult calibration and validation sample for the NIH Toolbox Emotion Module was only 10% African American/Black.

A novel finding of this study was that purpose in life was negatively associated with working memory in Hispanics. These results are not consistent with those in a previous sample that was approximately 90% non-Hispanic white (Wilson et al., 2013; Boyle, Buchman, Barnes, & Bennett, 2010). In another study, greater purpose in life was associated with worse cognition in middle-aged control subjects, but the sample size was very small (N=11), and race/ethnicity information was not reported (Hollinger et al., 2016). Studies specifically examining the relationship between purpose in life and cognition among Hispanics are severely lacking. One potential explanation for the current cross-sectional results is that greater purpose in life among Hispanics in this study may reflect enhanced meaning-making in response to early cognitive impairment, as Hispanics scored lower on the cognitive tests than the other racial/ethnic groups. It is also notable that the negative associations between positive psychosocial factors (i.e., emotional support, purpose in life) and cognition among Hispanics in the multivariate model were limited to the NIH Toolbox List Sorting test and were not found for any of the traditional paper-and-pencil tests. Because List Sorting is a research-based measure, the clinical significance of these negative associations is unclear.

The majority of positive psychosocial factors examined in this study were not significantly associated with any of the cognitive domains. It is unlikely that the inclusion of covariates that could theoretically mediate associations between these other psychosocial factors and cognition masked evidence of their protective effects. This is because sensitivity analyses omitting sadness and/or health status covariates did not reveal additional positive associations. Previous studies may have found evidence for protective effects of other positive psychosocial factors because they did not consider the related factor of self-efficacy or because samples largely comprised non-Hispanic Whites. Indeed, the current study did find a positive association between social support (i.e., NIH Toolbox Friendship survey) and working memory (i.e., NIH Toolbox List Sorting task) among Whites. Further, within-group bivariate associations revealed many more positive associations between the psychosocial factors and cognition for Whites than for Blacks or Hispanics. One exception to this overall pattern of results for Whites and Blacks is self-efficacy, which was positively associated with more cognitive domains for Blacks than for Whites in bivariate analyses.

A primary limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which precludes further exploration of the direction of effects involving different aspects of social support, purpose in life, and cognitive abilities. There was also a small but significant difference in age across Hispanics and non-Hispanics in this study, which was managed by including age as a covariate in all models. Another limitation is our inability to fully characterize the unique sociocultural experiences of Black, Hispanic, and White participants in this study. Specifically, the variables examined were insufficient in explaining negative associations involving emotional support and purpose in life. Thus, the results of this study highlight the need for additional work on how cultural variation influences psychosocial functioning, cognition, and our methods of measuring these constructs. A further limitation of this work is the use of self-reported presence of medical conditions (regardless of treatment) as the health status covariate. It is noted that self-reported conditions were significantly associated with both psychosocial and cognitive functioning, but it is likely these variables fail to capture the full variance in physical health. Strengths of this study include its racial/ethnic diversity, which allowed us to directly test for differences in associations between positive psychosocial factors and cognition across Blacks, Hispanics, and Whites living in the same geographic region. While these groups were not matched on relevant characteristics such as education or health status, such differences reflect real socioeconomic and health disparities across race/ethnicity in the U.S. and reinforce the representativeness of the current sample. In addition, this study featured a comprehensive neuropsychological battery administered in person. This battery comprised both traditional paper and pencil tests as well as newly-developed computer-based tests standardized in a large, national sample that allowed us to examine a wide range of cognitive domains. Of note, positive associations between self-efficacy and cognition were identified for both a research-based NIH Toolbox cognitive measure (i.e., Flanker) as well as traditional language tests (i.e., naming, verbal fluency, verbal abstraction, repetition, and comprehension) that are commonly used clinically.

Conflicting patterns of association between certain psychosocial factors and cognition between Hispanics and Whites indicate that previous studies of the role of social support and purpose in life in cognitive aging may not be generalizable to Hispanic older adults. Additional longitudinal work is needed to determine whether negative relationships between these psychosocial factors and cognition in Hispanics reflect low construct validity of NIH Toolbox psychosocial assessments for older Hispanics, reverse causation, threshold effects, and/or negative aspects of having a strong social network. This study also confirmed and extended the link between self-efficacy and cognition in late life, adding to the substantial observational literature supporting self-efficacy beliefs as a potential intervention target to optimize cognitive aging for some older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data collection and sharing for this project was supported by the Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP, PO1AG07232, R01AG037212, RF1AG054023) funded by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and through NIA grant number R00AG047963. This manuscript has been reviewed by WHICAP investigators for scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous WHICAP Study publications. We acknowledge the WHICAP study participants and the WHICAP research and support staff for their contributions to this study. This publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR001873. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aday L. At risk in America. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Regulation of cognitive processes through perceived self-efficacy. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25:729–735. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes LL, Mendes de Leon CF, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology. 2004;63:2322–2326. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147473.04043.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, Statistical Methodology. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL. The Visual Retention Test. New York: The Psychological Corporation; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Amarel D. Effects of social support visibility on adjustment to stress: experimental evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:458–475. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Cella DF, Hahn EA, Bjordal K, Sperner-Unterweger B, Gangeri L, … Zittoun R. Multilingual translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system. Quality of Life Research. 1996;5:309–320. doi: 10.1007/BF00433915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:304–310. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschke H, Fuld PA. Evaluating storage, retention, and retrieval in disordered memory and learning. Neurology. 1974;24:1019–1025. doi: 10.1212/wnl.24.11.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carretti B, Borella E, Zavagnin M, De Beni R. Impact of metacognition and motivation on the efficacy of strategic memory training in older adults: analysis of specific, transfer, and maintenance effects. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2011;52:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casaletto KB, Umlauf A, Marquine M, Beaumont JL, Mungas D, Gershon R, … Heaton RK. Demographically corrected normative standards for the Spanish language version of the NIH Toolbox cognition battery. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2016;22:364–374. doi: 10.1017/S135561771500137X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Hadi AS, Price B. Regression Analysis by Example. 3. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Del Ser T, Gonzálex-Montalvo JI, Martínez-Espinosa S, Delgado-Villapalos C, Bermejo F. Estimation of premorbid intelligence in Spanish people with the Word Accentuation Test and its application to the diagnosis of dementia. Brain and Cognition. 1997;33:343–356. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1997.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Venegas C, Downer B, Langa KM, Wong R. Racial and ethnic differences in cognitive function among older adults in the USA. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2016;31:1004–1012. doi: 10.1002/gps.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellwardt L, Aartsen M, Deeg D, Steverink N. Does loneliness mediate the relation between social support and cognitive functioning in later life? Social Science and Medicine. 2013;98:1116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2005;28:212–232. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1707–1736. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles LC, Anstey KJ, Walker RB, Luszcz MA. Social networks and memory over 15 years of follow up in a cohort of older Australians: results from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Journal of Aging Research. 2012:856048, 1e7. doi: 10.1155/2012/856048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glei DA, Landau DA, Goldman N, Chuang YL, Rodriguez G, Weinstein M. Participating in social activities helps preserve cognitive function: an analysis of a longitudinal, population-based study of the elderly. International Journal of epidemiology. 2005;34:864–871. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger KR, Franke C, Arenivas A, Woods SR, Mealy MA, Levy M, Kaplin AI. Cognition, mood, and purpose in life in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2016;362:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kats D, Patel MD, Palta P, Meyer ML, Gross AL, Whitsel EA, … Heiss G. Social support and cognition in a community-based cohort: the Atheroschlerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Age and Ageing. 2016;45:475–480. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lövdén M, Ghisletta P, Lindenberger U. Social participation attenuates decline in perceptual speed in old and very old age. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:423–434. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.3.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JJ, Bell-McGinty S, Tang MX, Schupf N, Stern Y, Mayeux R. Implementing diagnostic criteria and estimating frequency of mild cognitive impairment in an urban community. Archives of Neurology. 2005;62:1739–1746. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.11.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin G, Marin BV. Research with Hispanic populations. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S, editor. Mental status examination for organic mental syndrome in the elderly patient. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M, Berkman LF, Niedhammer I, Chea M, Goldberg M. Social relations and self-reported health: a prospective analysis of the French Gazel cohort. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:1817–1830. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer SC, Holtzer R. The differential relationships of dimensions of perceived social support with cognitive function among older adults. Aging and Mental Health. 2016;20:727–735. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1033683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen W. The Rosen Drawing Test. Bronx, NY: Veterans Administration Medical Center; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Salsman JM, Butt Z, Pilkonis PA, Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Hendrie HC, … Cella D. Emotion assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80:S76–S86. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman T, McAvay G, Merrill S, Albert M, Rodin J. Self-efficacy beliefs and change in cognitive performance: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Psychology and Aging. 1996;11:538–551. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.11.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Lusignolo TM, Albert M, Berkman L. Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Health Psychology. 2001;20:243–255. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.4.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siedlecki KL, Manly JJ, Brickman AM, Schupf N, Tang MX, Stern Y. Do neuropsychological tests have the same meaning in Spanish speakers as they do in English speakers? Neuropsychology. 2010;24:402–411. doi: 10.1037/a0017515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Chen X, Heller K. Too much of a good thing? Intergenerational social support and the psychological well-being of older parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58:970–982. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Y, Andrews H, Pittman J, Sano M, Tatemichi T, Lantigua R, Mayeux R. Diagnosis of dementia in a heterogeneous population. Development of a neuropsychological paradigm-based diagnosis of dementia and quantified correction for the effects of education. Archives of Neurology. 1992;49:453–460. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530290035009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Cross P, Andrews H, Jacobs DM, Small S, Bell K, … Mayeux R. Incidence of AD in African-Americans, Caribbean Hispanics, and Caucasians in northern Manhattan. Neurology. 2001;56:49–56. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Toler Woodward A, Brown E. Racial and ethnic differences in extended family, friendship, fictive kin and congregational informal support networks. Family Relations. 2013;62:609–624. doi: 10.1111/fare.12030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. interim projections by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin. 2004 Retrieved October 5, 2016. http://www.census.gov/ipc/www/usinterimproj/

- Weintraub S, Dikmen SS, Heaton RK, Tulsky DS, Zelazo PD, Bauer PJ, … Gershon RC. Cognition assessment using the NIH Toolbox. Neurology. 2013;80:S54–S64. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182872ded. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Segawa E, Yu L, Begeny CT, Anagnos SE, Bennett DA. The influence of cognitive decline on well-being in old age. Psychology and Aging. 2013;28:304–313. doi: 10.1037/a0031196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RA, Dismukes A. Cardiovascular effects of experimentally induced efficacy (ability) appraisals at low and high levels of avoidant task demand. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:172–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1995.tb03309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Meyer OL, Choi E, Thomas ML, Willis SL, Marsiske M, … Parisi JM. External locus of control contributes to racial disparities in memory and reasoning training gains in ACTIVE. Psychology & Aging. 2015;30:561–572. doi: 10.1037/pag0000042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Nowinski C, Gershon R, Manly JJ. Which psychosocial factors best predict cognitive performance in older adults? Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2014a;20:487–495. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne LB, Nowinski CJ, Gershon RC, Manly JJ. Depressive symptoms are more strongly related to executive functioning and episodic memory among African American compared to non-Hispanic White older adults. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2014b;29:663–669. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acu045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.