Abstract

BACKGROUND

This study examined (a) the direct association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity among adult Hispanic immigrants; (b) the indirect association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity via social support; and (c) if gender moderates the direct and indirect associations between family cohesion and alcohol use severity.

METHOD

Mediation and moderation analyses were conducted on a cross-sectional sample of 411 (men = 222, women = 189) participants from Miami-Dade, Florida.

RESULTS

Findings indicate that higher family cohesion was directly associated with higher social support and lower alcohol use severity. Higher social support was also directly associated with lower alcohol use severity. Additionally, family cohesion had an indirect association with alcohol use severity via social support. Moderation analyses indicated that gender moderated the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity, but did not moderate the indirect association.

CONCLUSIONS

Some potential clinical implications may be that strengthening family cohesion may enhance levels of social support, and in turn, lower alcohol use severity among adult Hispanic immigrants. Furthermore, strengthening family cohesion may be especially beneficial to men in efforts to lower levels of alcohol use severity.

Keywords: alcohol, family cohesion, social support, Hispanic, immigrants, gender differences

It is estimated that 56.6 million people of Hispanic heritage reside in the United States (U.S.) and 35% of this population are foreign-born (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). Although native-born and foreign-born segments of the U.S. Hispanic population are projected to grow (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015)—alcohol use among Hispanics has been under-researched in comparison to non-Hispanic Whites (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2016). A review of the literature indicates that alcohol studies focused on Hispanic immigrants are especially limited (Szaflarski, Cubbins, & Ying, 2011)—one explanation for this could be that Hispanic immigrants are studied to a lesser extent because epidemiological studies indicate that this population drinks less alcohol and are less likely to meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder in comparison to their U.S.-born counterparts (Alegría et al., 2008; Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Clark, Terzis, & Córdova, 2014). These differences in alcohol use behavior are characteristic of the immigrant paradox which proposes that foreign nativity protects against substance use disorders despite the risk factors that are often associated with immigration (e.g., acculturation stress, lower socioeconomic status; Alegría et al., 2008; Salas-Wright et al., 2014).

Regardless of nativity status, the lack of alcohol research is concerning because collectively Hispanics (compared to non-Hispanic ethnic groups) are more likely to engage in heavy drinking and experience alcohol-related disparities such as higher rates of citations for driving under the influence of alcohol and chronic liver disease (Field et al., 2015; National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2013; Sy, Ching, Olivares, Vinas, Chang, & Bergasa, 2017; Vaeth, Wang-Schweig, & Caetano, 2017). From public health and clinical perspectives, identifying and understanding mutable determinants of alcohol use behavior among Hispanic immigrants is increasingly important in efforts to prevent the development of alcohol use disorders and reduce alcohol-related disparities.

With this in mind the present study sought to expand this body of literature via the following aims: (a) examine the direct association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity among adult Hispanic immigrants, (b) examine the indirect association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity via social support; and (c) examine if gender moderates the direct and indirect associations between family cohesion and alcohol use severity. These study aims were guided by the framework of the Reserve Capacity Model (Gallo & Matthews, 2003; Gallo, Penedo, Espinosa de los Monteros, & Arguelles, 2009), which proposes that a positive social context (e.g., strong family cohesion) may enhance resilient factors (e.g., social support), and in turn, reduce the probability of engaging in health risk behaviors (e.g., alcohol use).

Family Cohesion

Family cohesion is the emotional bond and connectedness among family members (Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Huesmann, & Zelli, 1997). Literature suggests that family cohesion may function as a protective factor against alcohol use disorders (and other substance use disorders) because it facilitates communication among family members and enhances adaptive family functioning (Baer, 2002; Unger et al., 2009). The proposed protective effect of family cohesion has been supported in prevention interventions with Hispanic adolescents which have indicated that targeting and strengthening family cohesion led to a reduction in substance use (Pantin et al., 2003; Prado et al., 2010). The protective effect of family cohesion on substance use behavior may be particularly salient among Hispanics because this ethnic group emphasizes the value of a strong family orientation and family loyalty (Marsiglia, Parsai, & Kulis, 2009; Miranda et al., 2000).

Although the link between family cohesion and alcohol use behavior has been empirically supported—a review of prior studies found that a majority of this research has been conducted on samples of Hispanic adolescents (Unger et al., 2009). To the knowledge of the authors, only two published studies with Hispanic adults have investigated the association between family cohesion and alcohol use behavior—one was conducted in Puerto Rico (Caetano, Vaeth, & Canino, 2016) and the other with Hispanic immigrants living in the United States (Dillon, De La Rosa, Sanchez, & Schwartz, 2012). Each of these studies indicated that stronger family cohesion was associated with lower levels of alcohol use. However, findings from the study conducted in Puerto Rico suggest that in some instances stronger family cohesion may not function as a protective factor that reduces levels of alcohol use. Instead stronger family cohesion may function as a protective factor against alcohol-related problems, and in turn, enable further alcohol consumption (Caetano et al., 2016).

Based on the literature in this field of study, it is the view of the authors that more research is needed on samples of Hispanic adults to accrue evidence that family cohesion is a factor that may be clinically significant in alcohol use interventions targeting adult Hispanic populations. Furthermore, investigators have called for research to identify and understand mediators in the relationship between family cohesion and alcohol use behavior (Caetano et al., 2016). As such, this study aimed to advance research on the mediating mechanisms between family cohesion and alcohol use behavior.

Social Support

One factor that may help explain the link between family cohesion and alcohol use behavior is social support because people of Hispanic heritage tend to prefer to reach out to family members for support instead of friends, neighbors, and coworkers (Keefe, Padilla, & Carlos, 1979; Rodriguez, Mira, Myers, Morris, & Cardoza, 2003). Social support refers to the degree to which members of an individual’s social network serve particular functions (e.g., provide information and guidance; affection; material aid; and empathetic understanding; Cohen, 2004; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991).

Prominent theories of health behavior propose that higher levels of social support may help an individual manage psychosocial stress more effectively, in turn, reducing the probability of using maladaptive coping strategies such as substance use (Cohen, 2004). Some literature also suggests that higher levels of social support are associated with higher perceptions of social integration, which in turn, have a beneficial effect on overall wellbeing (Armstrong, Birnie-Lefcovitch, & Ungar, 2005). Thus, social support may be a particularly relevant determinant of health behavior among immigrants because these individuals are adjusting to a new receiving culture. Empirical research substantiates the proposed beneficial effects of social support. Prior studies have indicated that adequate social support among Hispanic populations, including Hispanic immigrants, may function as a protective factor against excessive alcohol use (Cano et al., 2017; De La Rosa, Holleran, Rugh, & MacMaster, 2005; De La Rosa & White, 2001).

Gender

To better understand the etiology of alcohol use behavior and develop more efficacious interventions targeting alcohol use—it has been recommended that researchers examine potential gender differences, including among Hispanic populations (Amaro & Iguchi, 2006; HHS, 2016). Thus, taking into account gender differences in family cohesion, social support, and alcohol use behavior—it is plausible that the direct and indirect associations between family cohesion and alcohol use may be distinct for men and women.

Although a strong family orientation has been described as a value held by Hispanics regardless of gender (Marsiglia et al., 2009; Miranda et al., 2000)—one study found that stronger adherence to traditional gender roles were associated with stronger family cohesion among adolescent Hispanic girls; however, this association was not statistically significant among adolescent Hispanic boys (Lorenzo-Blanco, Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2013). One explanation for this finding is that Hispanic women are often socialized to function within the family as the key figures responsible for maintaining the family unified and the primary source of strength for the family (Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010). Conversely, literature on masculinity and Hispanic men has focused on negative conceptualizations of machismo which places an emphasis on individual power (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008). Yet, it should be noted that more contemporary views on masculinity among Hispanic men are more balanced and encompass a value of nurturance and protection of the family (Arciniega et al., 2008).

With regard to social support, one notable gender difference is that Hispanic women tend to report larger and more diverse social networks (Alcántara, Molina, & Kawachi, 2015). Another difference is that Hispanic women are more likely to seek out social support as a constructive coping strategy, in turn, reducing the probability of using alcohol or other substances (Araújo & Borrell, 2006). Lastly, epidemiological research has indicated that men consume more alcohol than women—a difference that has also been observed among Hispanic immigrants (Cano et al., 2017; SAMHSA, 2015). Gender differences in alcohol use may be particularly pronounced among Hispanic immigrants because drinking norms for men in the United States and Latin America tend to be relatively similar; however, drinking norms for women are more conservative in Latin America compared to the United States (Caetano & Clark, 2003).

Present Study

Based on the body of work reviewed, the following hypotheses are proposed. Hypothesis one, higher levels of family cohesion would be directly associated with higher social support and lower alcohol use severity. Hypothesis two, family cohesion would be indirectly associated with alcohol use severity via social support. Furthermore, the present study aimed to examine if gender would moderate the direct and indirect associations of family cohesion on alcohol use severity. However, due to the scarcity of studies on this subject a priori hypotheses regarding moderation effects were not proposed.

Method

Participants and Procedures

This cross-sectional study was approved by the institutional review board of a university in Miami, Florida and was comprised of a sample of 411 adult Hispanic immigrants living in Miami-Dade County. Participants in this study were recruited from the participant pool of a completed study that was conducted six years prior. However, it should be noted that the present study is independent of the previously completed study. Inclusion criteria for the present study were: (a) self-identifying as Hispanic or Latino; (b) currently residing in Miami-Dade County; and (c) intending to stay in the United States for at least three years. In addition to this inclusion criteria, when participants were enrolled into the study conducted six years prior they had to be between the ages of 18 to 34; emigrated from a Latin American country; and living in the United States for one year or less.

Respondent-driven sampling was the primary strategy used to recruit the initial participant pool—this is an approach that has been effective in recruiting participants from difficult-to-reach populations (Salganik & Heckathorn, 2004). Each participant (the seed) was encouraged to refer individuals from his or her social network who met eligibility criteria. Seeds were recruited with informational flyers posted in neighborhoods with a high proportion of Hispanic inhabitants, community health centers, and health fairs targeting Hispanics. A maximum of seven participants could be enrolled per seed.

Trained bilingual and bicultural research staff obtained written consent from all participants and conducted all interviews in Spanish. All interviews were confidential and were completed at a location agreed upon by both the research staff and participant. Research staff conducted each interview which required approximately one hour to complete. For their participation, participants received $20.

Measures

Demographics

Self-reported sociodemographic information included age, gender (0 = female, 1 = male), education level (0 = less than high school, 1 = completed high school or higher), annual household income (0 = $20,000 or less, 1 = more than $20,000), partner status (0 = no partner/single/divorced/separated/widow, 1 = has partner/married), and country of origin (0 = Cuba, 1 = non-Cuban).

Family Cohesion

Perceived family cohesion was measured with the corresponding subscale of the Family Functioning Scale (Bloom, 1985). This measure consisted of five self-reported items with response choices on a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (very untrue) to 4 (very true). Higher mean scores were indicative of stronger family cohesion. A sample item is, “There was a feeling of togetherness in our family.” The family cohesion subscale of the Family Functioning Scale has been used in multiple studies with English-speaking and Spanish-speaking Hispanic participants; and has demonstrated to have good reliability (Dillon, De La Rosa, & Ibañez; Lester et al., 2010; Marelich, Murphy, Payne, Herbeck, & Schuster, 2012). In this study the reliability coefficient of the family cohesion subscale was (α = .79).

Social Support

Perceived social support was measured with the Social Support Survey (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). This measure consisted of 19 self-reported items with response choices on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Higher mean scores were indicative of higher perceptions of social support. A sample item is, “Someone you can count on to listen to you when you need to talk.” Spanish versions of the Social Support Survey have been validated with Spanish speaking participants (Gómez-Campelo et al., 2014); and in this study the reliability coefficient was (α = .99).

Alcohol Use Severity

Alcohol use severity was measured with the Spanish version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001). The AUDIT consists of 10 self-reported items with varied response choices on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4. Summed scores range from 0 to 40 with higher scores indicating higher alcohol use severity. A sample item is, “How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?” The Spanish version of the AUDIT has been validated with Spanish speaking participants (Babor et al., 2001) and the reliability coefficient in this study was (α = .91).

Data Analytic Plan

The data analytic plan included three steps. First, descriptive statistics were computed and bivariate correlations were estimated for all variables used in the mediation and moderation analyses. Second, using PROCESS v2.13 (Hayes, 2013) we conducted a mediation analysis to examine the indirect association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity via social support. This method simultaneously estimates the direct association of X on Y (c-path), the direct association of X on M (a-path), the direct association of M on Y (b-path), and the indirect association of X (family cohesion) on Y (alcohol use severity) via M (social support). Third, PROCESS v2.13 was also used to test of gender moderated the direct and indirect associations of family cohesion on alcohol use severity. It should be noted that PROCESS only produces confidence intervals for unstandardized regression coefficients. All moderation analyses were conducted with 50,000 bootstraps and controlled for the sociodemographic variables.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Most participants reported being male (54%) and the mean age of the sample was 31.71 (SD = 4.99). Most participants also reported being single (53.5%), having completed an education of high school or higher (75.7%), and having an annual household income of $20,000 or less (61.3%). With regard to country of origin, 46.2% of participants emigrated from Cuba, 19.2% from Colombia, 10.5% from Honduras, 9.7% from Nicaragua, 1.5% from Mexico, and the remainder were from other Latin American countries. Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and frequencies by gender for all variables used in subsequent analyses. Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations for variables used in the mediation and moderation analyses.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Women (n=189) | Men (n=222) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | χ2 | |

| Education Level | |||

| > High School | 143 (75.7) | 168 (75.7) | 0.00 |

| Annual Household Income | |||

| ≥ $20,000 | 138 (73.0) | 114 (51.4) | 20.20*** |

| Partner Status | |||

| Single | 104 (55.0) | 116 (52.3) | .32 |

| Country of Origin | |||

| Cuba | 90 (47.6) | 100 (45.0) | .27 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | t value | |

| Age | 31.98 (5.14) | 31.47 (4.86) | 1.02 |

| Family Cohesion | 3.13 (.46) | 3.08 (.43) | 1.20 |

| Social Support | 3.96 (1.00) | 3.60 (1.07) | 3.53 |

| Alcohol Use Severity | 1.78 (3.44) | 4.87 (6.75) | −5.70** |

p < .001

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations for Variables Used in Mediation and Moderation Analyses (n = 411)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||

| 2. Gender | −.05 | - | |||||||

| 3. Partner Status | .00 | .03 | - | ||||||

| 4. Country of Origin | −.14** | −.03 | −.04 | - | |||||

| 5. Education Level | −.05 | .00 | .06 | −.16** | - | ||||

| 6. Household Income | −.01 | .22** | .19** | −.05 | −.25** | - | |||

| 7. Family Cohesion | .04 | −.06 | .02 | .06 | −.23** | −.08 | - | ||

| 8. Social Support | .05 | −.17** | −.03 | .12* | −.15** | −.11* | .48** | - | |

| 9. Alcohol Use Severity | −.01 | .27** | −.03 | −.12* | .08 | .14** | −.23** | −.24** | - |

p < .05;

p < .01

Mediation Analysis

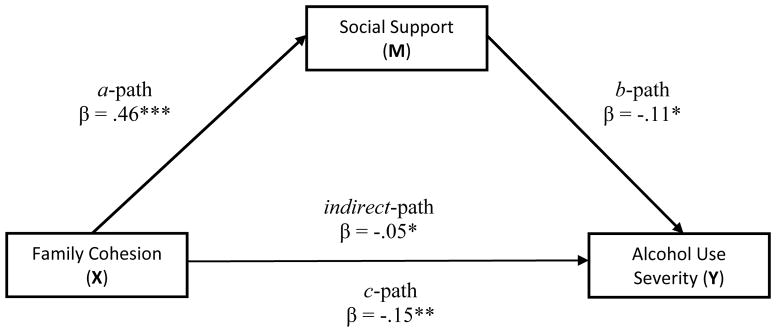

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual mediation model with standardized regression coefficients. Results indicate that family cohesion had statistically significant direct associations with social support (β = .46, p < .001) and alcohol use severity (β = −.15, p < .01). Similarly, social support had a statistically significant direct association with alcohol use severity (β = −.11, p < .05). Also, the indirect association of family cohesion on alcohol use severity was statistically significant (β = −.05, p < .05; b = −.64, 95% CI [−1.34, −.10]). Lastly, results from the mediation analysis indicate that all predictor variables in the model accounted for 14.27% of the variance of alcohol use severity [ΔR2 = 14.27, F(8, 402) = 8.36, p < .001].

Figure 1.

Conceptual mediation model with standardized regression coefficients.

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01; *** p < .001; X = predictor; M = mediator; Y = outcome. Mediation model controlled for age, gender, partner status, education level, annual household income, and country of origin.

Moderation Analyses

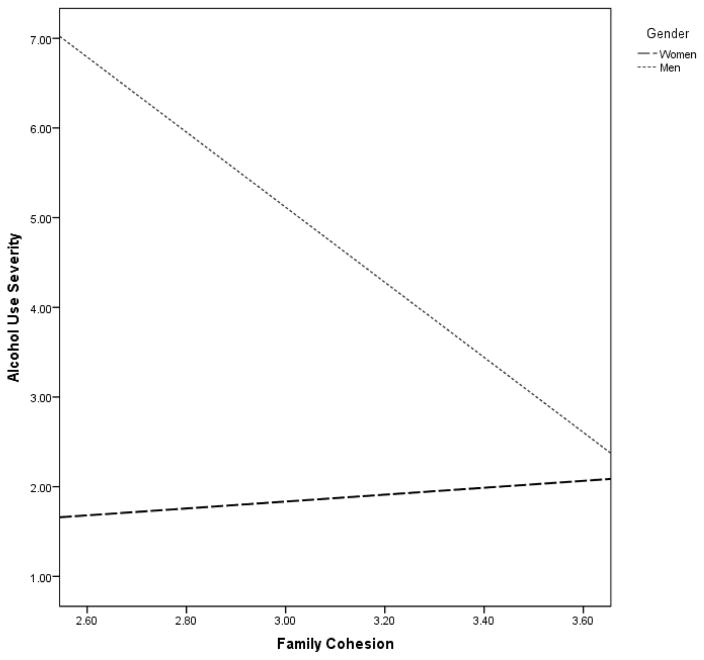

Another aim of the study was to examine if the direct and indirect associations between family cohesion and alcohol use severity were distinct between men and women. As such, moderation tests were conducted to estimate the modifying effects of gender. The first moderation test (depicted in Figure 2) examined if gender modified the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity. Results indicate that the interaction between family cohesion and gender in relation to alcohol use severity was statistically significant (β = −.36, p < .001; b = −4.67, 95% CI [−6.99, −2.24]). More specifically, conditional effects indicate that the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity was only statistically significant among men (β = −.33, p < .001; b = −4.30, 95% CI [−6.08, −2.52]) and not women (β = .03, p > .05; b = .37, 95% CI [−1.40, 2.13]). This moderation effect added 3.20% to the explained variance of alcohol use severity [ΔR2 = 3.20, F(1, 401) = 15.57, p < .001]. In turn, the moderation effect increased the total explained variance to 17.48% [ΔR2 = 17.48, F(9, 401) = 9.43, p < .001]. The second moderation test examined if gender modified the indirect association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity. However, results from this analysis were not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Gender moderating the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity.

Discussion

This study adds to the growing literature on alcohol use among adult Hispanic immigrants—key findings from the study can be summarized as follows. First, stronger family cohesion was directly associated with higher levels of social support and lower levels of alcohol use severity. Second, family cohesion had an indirect association with alcohol use severity via social support. Third, gender moderated the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity, but did not moderate the indirect association.

Direct Association of Family Cohesion

Although more studies are needed to advance the translation of our findings into the design of evidence-based interventions—results may have some future clinical implications. Findings suggest that targeting modifiable factors such as family cohesion among adult Hispanic immigrants may result in lower levels of alcohol use severity. This finding is encouraging because evidence-based interventions that aim to enhance family cohesion and other domains of family functioning have shown to prevent substance use disorders and reduce substance use (including alcohol use) among Hispanic adolescents (Pantin et al., 2003; Prado et al., 2010). As such, developing or tailoring existing interventions that target family cohesion may also prevent alcohol use disorders and reduce alcohol consumption among adult Hispanic immigrants.

Furthermore, findings from this study indicate that the association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity was especially beneficial for men. To the knowledge of the authors, this is the first study among Hispanic adults that examined gender differences in the relationship between family cohesion and alcohol use (or other forms of substance use). One possible explanation for this gender difference is that a higher level of family cohesion among men may offset “negative” characteristics of machismo such as encouraging the use of alcohol consumption and placing an emphasis on individual power (Arciniega el al., 2008; Lawrence, Abel, & Hall, 2010).

Indirect Association of Family Cohesion

Consistent with existing literature (Cano et al., 2017; De La Rosa et al., 2005; De La Rosa & White, 2001), findings from this study suggest that higher levels of social support were associated with lower alcohol use. Perhaps more importantly, this study found that social support functioned as a mediating mechanism that linked the association between family cohesion and alcohol use. More specifically, higher levels of family cohesion were associated with higher levels of social support, and in turn, higher levels of social support were associated with lower levels of alcohol use severity. As such, these findings lend support to the Reserve Capacity Model.

A moderation test found that gender did not modify the indirect association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity. This finding indicates that the mediating role of social support functioned equally for men and women. From a clinical perspective, this finding may be relevant because it offers an empirical explanation on how family cohesion may reduce alcohol use severity. Given that gender did not moderate the indirect effect of family cohesion this suggests that another mediating mechanism may explain the observed gender difference in the direct association between family cohesion and alcohol use severity. Considering the prominent role of mediating factors in intervention science (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007) and the limited literature in this field of research, more studies are needed to examine potential mediators between family cohesion and alcohol use severity in order to better inform the design or modification of clinical interventions.

Limitations

The following limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, due to the cross-sectional design, a causal or directional order of the associations found cannot be made. Second, the present study used non-probability sampling and instead relied on respondent-driven sampling because the target population (e.g., Spanish-speaking Hispanic immigrants) is difficult to reach and enroll in health-related research studies (Aponte-Rivera et al., 2014; Martinez, McClure, Eddy, Ruth, & Hyers, 2012). Third, self-report measures were utilized which may be susceptible to error and participant misrepresentation. Lastly, all study participants were immigrants living in Miami-Dade County, and most participants emigrated from Cuba. Although the study sample may be somewhat representative of the Hispanic immigrant community living in Miami-Dade County (Statistical Atlas, 2015)—generalizability to other Hispanic populations may be limited. Related to the issue of generalizability, it should be noted that people of Mexican heritage make up the majority of native-born and foreign-born Hispanics living in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016) and in the present study Mexican immigrants only made up 1.5% of the sample. As such, it is recommended that future studies be conducted with more diverse samples that reflect the broader Hispanic population.

Conclusion

Despite the noted limitations, the present study adds to the field of research on alcohol use behavior among adult Hispanic immigrants. To date, a significant majority of studies on family cohesion and alcohol use (or other substance use) among Hispanics have focused on adolescent populations—this study is one of three that investigated the effect of family cohesion on alcohol use among Hispanic adults and found a beneficial effect. In addition, this study is the first to initiate the exploration of mediating mechanisms (e.g., social support) and potential gender differences in the relationship between family cohesion and alcohol use among adult Hispanics.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [R21 AA022202] and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities [P20 MD002288].

Footnotes

Author Disclosures: All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest and do not have any financial disclosures to report.

References

- Amaro H, Iguchi MY. Opportunities in Hispanic drug abuse research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;84:S64–S75. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aponte-Rivera V, Dunlop BW, Ramirez C, Kelley ME, Schneider R, Blastos B, … Craighead WE. Enhancing Hispanic participation in mental health clinical research: Development of a Spanish-speaking depression research site. Depression and Anxiety. 2014;31:258–267. doi: 10.1002/da.22153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJ. Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a Traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55:19–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong MI, Birnie-Lefcovitch S, Ungar MT. Pathways between social support, family well being, quality of parenting, and child resilience: What we know. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:269–281. doi: 10.1007/s10826-005-5054-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Araújo BY, Borrell LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28:245–266. doi: 10.1177/0739986305285825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alcántara C, Molina KM, Kawachi I. Transnational., social., and neighborhood ties and smoking among Latino immigrants: Does gender matter. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:741–749. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The alcohol use disorders identification test: Guidelines for use in primary health care. 2. Geneva, CH: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Acculturation, alcohol consumption, smoking, and drug use among Hispanics. In: Chun KM, Organista PB, Marín G, editors. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Vaeth PA, Canino G. Family cohesion and pride, drinking and alcohol use disorder in Puerto Rico. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2016;43:87–94. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1225073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano MA, Sánchez M, Trepka MJ, Dillon FR, Sheehan DM, Rojas P, … La Rosa M. Immigration stress and alcohol use severity among recently immigrated Hispanic adults: Examining moderating effects of gender, immigration status, and social support. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2017;73:294–307. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Perez FV, Castillo R, Ghosheh MR. Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2010;23:163–175. doi: 10.1080/09515071003776036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, Caetano R. Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research and Health. 2010;33:152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist. 2004;59:676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa MR, Holleran LK, Rugh D, MacMaster SA. Substance abuse among U.S. Latinos: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2005;5:1–20. doi: 10.1300/J160v5n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M, White M. The role of social support systems in the drug use behavior of Hispanics revisited. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2001;33:233–241. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2001.10400570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, De La Rosa M, Ibañez GE. Acculturative stress and diminishing family cohesion among recent Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2013;15:484–491. doi: 10.1007/s10903-012-9678-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, De La Rosa M, Sanchez M, Schwartz SJ. Preimmigration family cohesion and drug/alcohol abuse among recent Latino immigrants. The Family Journal. 2012;20:256–266. doi: 10.1177/1066480712448860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Cabriales JA, Woolard RH, Tyroch AH, Caetano R, Castro Y. Cultural adaptation of a brief motivational intervention for heavy drinking among Hispanics in a medical setting. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:724. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1984-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Matthews KA. Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129:10–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo LC, Penedo FJ, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Arguelles W. Resiliency in the face of disadvantage: Do Hispanic cultural characteristics protect health outcomes? Journal of Personality. 2009;77:1707–1746. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Campelo P, Pérez-Moreno EM, de Burgos-Lunar C, Bragado-Álvarez C, Jiménez-García R, Salinero-Fort MÁ. Psychometric properties of the eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey based on Spanish outpatients. Quality of Life Research. 2014;23:2073–2078. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SA, Abel EM, Hall T. Protective strategies and alcohol use among college students: Ethnic and gender differences. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2010;9:284–300. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2010.522894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester P, Stein JA, Bursch B, Rice E, Green S, Penniman T, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Family based processes associated with adolescent distress, substance use and risky sexual behavior in families affected by maternal HIV. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:328–340. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. A longitudinal analysis of Hispanic youth acculturation and cigarette smoking: The roles of gender, culture, family, and discrimination. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2013;15:957–968. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelich WD, Murphy DA, Payne DL, Herbeck DM, Schuster MA. Self-competence among early and middle adolescents affected by maternal HIV/AIDS. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth. 2012;17:21–33. doi: 10.1080/02673843.2011.649398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez CR, McClure HH, Eddy JM, Ruth B, Hyers MJ. Recruitment and retention of Latino immigrant families in prevention research. Prevention Science. 2012;13:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda AO, Estrada D, Firpo-Jimenez M. Differences in family cohesion, adaptability, and environment among Latino families in dissimilar stages of acculturation. The Family Journal. 2000;8:341–350. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol and the Hispanic community. 2013 Retrieved February 18, 2017 from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/HispanicFact/HispanicFact.htm.

- Pantin H, Coatsworth JD, Feaster DJ, Newman FL, Briones E, Prado G, … Szapocznik J. Familias Unidas: The efficacy of an intervention to promote parental investment in Hispanic immigrant families. Prevention Science. 2003;4:189–201. doi: 10.1023/a:1024601906942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prado G, Huang S, Maldonado-Molina M, Bandiera F, Schwartz SJ, de la Vega P, … Pantin H. An empirical test of ecodevelopmental theory in predicting HIV risk behaviors among Hispanic youth. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37:97–114. doi: 10.1177/1090198109349218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N, Mira CB, Myers HF, Morris JK, Cardoza D. Family or friends: Who plays a greater supportive role for Latino college students? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:236. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Clark TT, Terzis LD, Córdova D. Substance use disorders among first- and second-generation immigrant adults in the United States: evidence of an immigrant paradox? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:958–967. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology. 2004;34:193–240. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Atlas. National origin in Miami-Dade County, Florida. 2015 Retrieved from http://statisticalatlas.com/county/Florida/Miami-Dade-County/National-Origin.

- Sy AM, Ching R, Olivares G, Vinas C, Chang R, Bergasa NV. Hispanic ethnicity is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Annals of Hepatology. 2017;16:169–171. doi: 10.5604/16652681.1226956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski M, Cubbins LA, Ying J. Epidemiology of alcohol abuse among U.S. immigrant populations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2011;13:647–658. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9394-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2014 National population projections: Summary tables. 2015 Retrieved from www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2014/summarytables.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. Hispanic Heritage Month 2016. 2016 Retrieved from www.census.gov/newsroom/facts-for-features/2016/cb16-ff16.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. 2016 Retrieved from https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/surgeon-generals-report.pdf. [PubMed]

- Vaeth PA, Wang-Schweig M, Caetano R. Drinking, alcohol use disorder, and treatment access and utilization among US racial/ethnic groups. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:6–19. doi: 10.1111/acer.13285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]