Abstract

Twenty-five primer pairs developed from genomic simple sequence repeats (SSR) were compared with 25 expressed sequence tags (EST) SSRs to evaluate the efficiency of these two sets of primers using 59 sugarcane genetic stocks. The mean polymorphism information content (PIC) of genomic SSR was higher (0.72) compared to the PIC value recorded by EST-SSR marker (0.62). The relatively low level of polymorphism in EST-SSR markers may be due to the location of these markers in more conserved and expressed sequences compared to genomic sequences which are spread throughout the genome. Dendrogram based on the genomic SSR and EST-SSR marker data showed differences in grouping of genotypes. A total of 59 sugarcane accessions were grouped into 6 and 4 clusters using genomic SSR and EST-SSR, respectively. The highly efficient genomic SSR could subcluster the genotypes of some of the clusters formed by EST-SSR markers. The difference in dendrogram observed was probably due to the variation in number of markers produced by genomic SSR and EST-SSR and different portion of genome amplified by both the markers. The combined dendrogram (genomic SSR and EST-SSR) more clearly showed the genetic relationship among the sugarcane genotypes by forming four clusters. The mean genetic similarity (GS) value obtained using EST-SSR among 59 sugarcane accessions was 0.70, whereas the mean GS obtained using genomic SSR was 0.63. Although relatively lower level of polymorphism was displayed by the EST-SSR markers, genetic diversity shown by the EST-SSR was found to be promising as they were functional marker. High level of PIC and low genetic similarity values of genomic SSR may be more useful in DNA fingerprinting, selection of true hybrids, identification of variety specific markers and genetic diversity analysis. Identification of diverse parents based on cluster analysis can be effectively done with EST-SSR as the genetic similarity estimates are based on functional attributes related to morphological/agronomical traits.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1172-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Dedrogram, EST, Genetic diversity, Polymorphism information content, SSR

Introduction

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrids) being one of the important multipurpose agricultural crops cultivated in both tropical and sub-tropical countries accounts for nearly 80% of the white sugar production worldwide. Sugarcane belongs to the genus Saccharum and family Poaceae and composed of hybrids mainly derived from Saccharum officinarum and Saccharum spontaneum (Roach 1972). Sugarcane genome is highly complex due to its interspecific origin, large size and high degree of complex polyploidy (Singh et al. 2011). It also exhibits variable number of somatic chromosomes due to multispecies origin. Hence genetic studies in sugarcane received little attention compared to the other diploid crops (Grivet and Arruda 2001). In addition, only limited number of parental clones involved in genetic makeup of sugarcane which resulted in the narrow genetic base of the modern cultivars is the main cause of slow progress in varietal release for sugarcane (Singh et al. 2011). The essential step in genetic base broadening programme is to utilize the germplasm with sufficient genetic variation which reflects on agronomical traits (Ahmed and Gardezi 2017). Hence determination and utilization of the natural variation present in the domestic cultivars and wild relatives will accelerate the varietal development programme (Cordeiro et al. 2001).

Genetic variation in sugarcane can be assessed with morphological markers (Perera et al. 2012), agronomical traits (Brasileiro et al. 2014) and molecular markers (Cordeiro et al. 2003). Although morphological markers and agronomical traits are easy to record, they are less reproducible due to the limited number of traits and highly influenced by the environment. On the contrary, molecular markers which exhibit environment independent expression are now routinely used in genetic studies in sugarcane. Among the molecular markers, SSR markers were more efficient in overcoming the limitations posed by morphological markers; hence, they were widely used in comparative mapping (Piperidis et al. 2008; Raboin et al. 2006), linkage map construction (Andru et al. 2011; Oliveira et al. 2007), germplasm characterization (Cordeiro et al. 2003), paternity analysis (Tew and Pan 2010; Ahmad et al. 2017), varietal testing (Pan 2006), association mapping (Racedo et al. 2016) and genetic analysis (Pashley et al. 2006). SSRs can be identified from either genomic DNA or cDNA sequences. Abundance in plant genome, reproducibility and high polymorphic nature make genomic SSR markers more attractive and dependable. SSR markers derived from genomic libraries amplified more fragments and showed more polymorphism within sugarcane (Cordeiro et al.2001; Pinto et al. 2006; Kalwade and Devarumath 2014). However, most of the genomic markers are likely to have no close linkage to transcribed regions and thus have no defined genic function (Hu et al. 2011). On the contrary, SSR markers derived from EST sequences are functionally important than genomic markers because they are present in the expressed regions of the genome (Casu et al. 2001; Carson and Botha 2000). EST-SSR markers have relative advantage over genomic SSR because they are quickly obtained by electronic search and it reflects the genetic diversity inside or adjacent to the genes (Varshney et al. 2005). In the complex genome crops like sugarcane, gene characterization is achieved significantly using EST markers (Oliveira et al. 2009). ESTs are important resource for gene discovery, gene expression, molecular marker development and comparative genomics. In sugarcane large number of genomic SSR and EST-SSR were developed and deployed in various genetic analyses (Singh et al. 2008; Pan 2006).

Genomic SSR and EST-SSR differ in assessing genetic diversity of species, because they come from different regions of genomes as reported in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and other plants (Chen et al. 2009; Wen et al. 2010). Different types of molecular markers have been used in genetic diversity analysis among populations and screening of candidate genes associated with targeted traits. Sugarcane has larger genome, can be characterized with larger amount of genomic SSR markers resulting in better map coverage and even un-transcribed regions can be covered by genomic SSRs. High cross transferability to related species and utilization in comparative mapping and evolution studies are the advantages of EST-SSR. In Marker Aided Selection (MAS), combination of genomic SSR and EST-SSR provides the opportunities for more complete scan of the genome. Although both the markers systems are used in genetic studies and diversity analysis, comparative efficiency of these marker systems was not reported in sugarcane. In the present study, genomic and EST SSRs were analyzed for different genetic parameters and interpretations on relative advantage of specific markers system for specific studies are presented.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Fifty-nine sugarcane accessions representing commercial hybrids, pre-breeding genetic stocks, and interspecific and intergeneric hybrids involving related species and genera in Saccharum complex were obtained from ICAR–Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, India. Table 1 illustrates the list of clones used and their parentage. The quantitative traits, viz. plant height, cane weight and the qualitative traits, viz. juice brix, fibre % and % of dry weight of the selected clones are presented in Online Resource 1.

Table 1.

Parentage of the 59 sugarcane genotypes used for estimating the genetic diversity analysis

| S. no | Clone name | Parentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | BM 10218 | 81V48 X (Co1148 X IND 84-415) |

| 2 | BM 10216 | 81V48 X (Co1148 X IND 84-415) |

| 3 | BM 10206 | Co 86002 X SES132B |

| 4 | BM 10202 | Co 86002 X SES132B |

| 5 | BM 10194 | Co 86002 X SES132B |

| 6 | BM 10186 | Co 62198 X 355 (BO X S. spontaneum) |

| 7 | BM 10173 | ISH 100 X 1A 3107 |

| 8 | BM 10214 | 81 V 48 X (Co 1148 X 1ND 84-415) |

| 9 | BM 10209 | Co 86002 X SES 132B |

| 10 | BM 10200 | Co 86002 X SES 132B |

| 11 | BM 10185 | ISH 100 X PL 480-376 |

| 12 | BM 10100 | 9861009 X SSCD 922 |

| 13 | BM 10104 | 013504 X Co 0218 |

| 14 | BM 10177 | 038701 X Co 62198 |

| 15 | BM 10123 | MS 6847 X 87-145 |

| 16 | BM 10125 | 81 V 48 X SSCD 1742 |

| 17 | BM 10129 | Co 86002 X SES 140 |

| 18 | BM 10152 | Co 07001 X SES 180A |

| 19 | 039301 | 013502 X (Co 7201 X SES 138) |

| 20 | 013102 | IK 76-92 X SES 517 |

| 21 | BM 10212 | 037702 X Co 62198 |

| 22 | BM 10210 | 037702 X Co 62198 |

| 23 | BM 10217 | 037702 X Co 62198 |

| 24 | BM 10195 | 037702 X Co 62198 |

| 25 | BM 09294 | 28NG78 X 037703 |

| 26 | BM 09295 | 28NG78 X 037703 |

| 27 | BM 09293 | 013504 X Co 0218 |

| 28 | BM 09285 | IK76-92 X 98N1 1405 |

| 29 | BM 09282 | IK76-92 X 98N1 1405 |

| 30 | BM 09278 | 98N1 1303 X 037703 |

| 31 | BM 09280 | 57NG77stir X 037703 |

| 32 | BM 09274 | 038701 X Co 775 |

| 33 | BM 09292 | 013502 X Co 0218 |

| 34 | BM 09287 | IK76-92 X 98N1 1405 |

| 35 | BM 09283 | IK76-92 X 98N1 1405 |

| 36 | BM 09281 | 038701 X Co 62198 |

| 37 | BM 09277 | 98N1 1303 X 037703 |

| 38 | BM 09275 | NG 77-49 X 037703 |

| 39 | BM 10136 | 037802 X CoJ 03193 |

| 40 | 0416907 | 037801 X 986079 |

| 41 | BM09291 | 013502 X Co 0218 |

| 42 | ISH 226 | 51NG 53 X MS 68147 |

| 43 | 012907 | KRS 6 X N2S1-0111 (Uahi-e-pele//28 NG 51/SES 44A) |

| 44 | 015001 | NG 77-99 X KRS 3 |

| 45 | 021110 | (98N2 1903 X IK 76-92/17) SELFS OF N2 |

| 46 | 012906 | KRS 6 X N2S1 0111 (Uahi-e-pele//28 NG 51/SES 44A) |

| 47 | 014902 | NG 77-99 X KRS 7 |

| 48 | 015003 | NG 77-99 X KRS 3 |

| 49 | ISH 175 | Mangwa X Co 1148 |

| 50 | 987047 | Co 8353 X Co 86011 |

| 51 | 972527 | Co 8371 X Co 86249 |

| 52 | NG 77-18 | S. officinarum |

| 53 | 987479 | CoA 7602 X 87A 380 |

| 54 | 9866142 | Co 89009 X CN1C-618(Co 7201////28 NG 210/SES 871//NG 77-99/SES 87A///Co 62198) |

| 55 | 972111 | CN22-41093 (CoC 671////NG 77-99//28 NG 51/SES 44A///NG 77-137/SES 538) X Co 88013 |

| 56 | 98 N1 1307 | N2 1902 X IK 76-81 |

| 57 | 012706 | NG 77-38 X 98N1 1302 |

| 58 | 971522 | Co 7201(R) X N22-3506 (NG 77-99//28 NG 51/SES 44A///28 NG 210//28 NG 51/SES 131) |

| 59 | Q 63 | TROJAN X CP 29-116 |

DNA extraction and Quality check

Tender stem tissue samples were collected and DNA was isolated using CTAB method (Doyle and Doyle 1987). The quality and quantity of the DNA samples were checked in NanoDrop (ND-1000, version 3.1.1, USA).

Primers, PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) amplification and electrophoresis

Fifty SSR primers were used in this study to analyze the genetic diversity among the 59 sugarcane genotypes. Out of these 50 primer pairs, 25 SSR primers were derived from EST database and 25 SSR primers were designed from the genomic sequences. EST SSR primers were associated with wide range of gene function including transmembrane glycoprotein (NKS 1), cytochrome P450 (NKS 2) (Carson and Botha 2000), acid invertase (NKS 3) (Carson et al. 2002), WRKY 1 (SCB 190) (Yilmaz et al. 2009), peroxidise precursor protein (SCB 243) (Liu et al. 2008), ENTH (epsin N-terminal homology) domain containing protein (SCB 254) (Lin et al. 1999), pherophorin like protein (SCB 474) (Soderlund et al. 2009), uridylate kinase protein (SCB 486) (Chen et al. 2009), endosperm surrounding region family protein (SCB 429) (Kinoshita et al. 2007), ATP binding protein (SCB 378) (Chan et al. 2009) and Vesicle Associated Membrane Proteins (SCB 370) (Alexandrov et al. 2009).

Among the EST primers, 16, 6 and 3 primers were reported by Marconi et al. (2011), Singh et al. (2008) and Govindaraj et al. (2005), respectively. Among genomic SSR primers, 14 and 11 primers were reported by Govindaraj et al. (2005) and Cordeiro et al. (2000), respectively. The details of the primers are given in Online Resource 2. Different types of repeat motifs, viz. di, tri and tetra nucleotide repeats present in the genomic and EST-SSR markers are summarized in Online Resource 2. Among the genomic SSR sequences, dinucleotide repeats were common whereas trinucleotides were abundant among EST-SSR.

All the primers were standardized for annealing temperature using gradient PCR to improve the specificity of the primers. The DNA samples were diluted to get a final concentration of 20 ng/µl for PCR amplification. The PCR reaction was performed in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf Mastercycler Pro S, Germany) using a 10 µl reaction mix consisting final concentration of 20 ng template DNA, 25 pmol each of forward and reverse primers, 0.3 unit Taq polymerase (Merck, India), l× Taq Buffer (Merck, India) and 100 μM dNTPs (Merck, India). The PCR cycle consisted of 2 min at 95 °C followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C, 40 s at the annealing temperature standardized for each primer (ranging from 50 to 64 °C), 40 s extension at 72 °C and a final extension of 7 min at 72 °C. PCR products were resolved in 8% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels in a vertical electrophoresis apparatus (Scie-Plas, UK) and stained with silver nitrate. The size of the amplified fragment was estimated using 100 bp DNA ladder and gel documentation was done using Alpha Imager.

Band scoring and analysis

DNA bands were scored for the presence (1) or absence (0) in all 59 genotypes and the data were used to calculate the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient (JSCs) using NTSYS-pc software, Numerical Taxonomy System, Version 2.10 (Applied Biostatistics, Inc., Setauket, NY, USA). Genetic distances between each pair of lines were estimated as D = 1−JS. Dendrogram was constructed using Unweighted Pair Group Method of Arithmetic mean (UPGMA), algorithm in NTSYS-pc. PIC was calculated using the formula, PIC = 1−ΣPij2 (Anderson et al. 1993), where Pij is the frequency of the jth allele for ith locus summed across all alleles for the locus.

Results and discussion

Number of markers generated by different types of primers

Genomic SSR markers were compared with EST-SSR markers for the number of amplicons generated, PIC, percentage of polymorphism and ability to estimate the genetic relationships among sugarcane clones. Both genomic SSR and EST-SSR markers amplified distinct banding patterns with varying degrees of polymorphism among the 59 sugarcane genotypes. Genomic SSR primers generated more markers than the EST-SSR primers. The number of markers ranged from 6 (NKS 56) to 25 (SMC336BS) for genomic SSR primers and for the EST-SSR the number of markers ranged from 3 (SCB 243) to 31 (SCB 365). The 25 genomic SSR primers generated 374 markers with a mean of 14.96 markers per primer while 25 EST primers produced 350 markers with a mean of 14 markers per primer. Multiple alleles generated by the SSR primers are due to the polyploidy, aneuploidy and larger size of the sugarcane genome (Singh et al. 2017). Generation of high number of marker per primer justified the right selection of primers for genetic diversity analysis. More than 10 amplicons per primer were also reported by You et al. (2016) and Singh et al. (2011).

Out of 724 SSR markers amplified by both genomic SSR and EST-SSR primers, 721 markers were found to be polymorphic (99.58%) with an average of 14.48 polymorphic markers per primer. Nine primers, namely, SCB429, SCB371, SCB370, SCB365, SMC336 BS, SMC486CG, MSSCIR43, NKS50 and NKS42 produced more than 20 markers. Other 26 primers, viz., SCM18, SCB190, SCB208, SCB254, SCB486, SCB484, SCB474, SCB457, SCB378, SCB271, UGSM36, UGSM49, UGSM193 mSSCIR66, SMC703BS, SMC278CS, SMC31CUQ, SM569CS, MSSCIR4, MSSCIR1, NKS52, NKS51, NKS48, NKS45, NKS11 and NKS17 generated markers between 11 and 20. The remaining fifteen primers, namely, SCM7, NKS3, NKS2, NKS1, SCB243, SCB246, SCB441, UGSM141, SMC1604SA, NKS56, NKS46, NKS33, NKS32, NKS7 and NKS8 produced less than 11 markers. Comparison between genomic SSR and EST-SSR in terms of markers generated and marker size (bp) are illustrated in Table 2. Seven and eight primers of genomic and EST SSR primers, respectively, generated low number of markers (between 1 and 10) whereas 13 genomic and EST-SSR primers each generated medium number of markers (11–20). More than 21 markers were generated by 5 and 4 genomic and EST SSR primers, respectively. The size of the amplicons produced by different primers system also varied greatly. Each 3 genomic and EST SSR primers generated marker size of less than 300 bp while 11 genomic and 12 EST-SSR primers generated marker size between 301 and 500 bp. Eleven genomic and 10 EST-SSR primers generated the marker size of above 500 bp. The results indicated that the size of the markers produced by both the marker systems did not show any variation.

Table 2.

Efficiency of EST SSR and genomic SSR primers in generating markers and size of amplicons

| Primers | Markers generated | Marker size (bp) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–10 | 11–20 | 21 < | > 300 | 300–500 | 501 < | |

| Genomic SSR | 7 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 11 |

| EST SSR | 8 | 13 | 4 | 3 | 12 | 10 |

Efficiency of genomic SSR and EST-SSR in discriminating the progenies with common parents

Genetically, sugarcane is heterozygous and homogenous. Since the parents used are heterozygous in nature, the hybrids also segregate for several characters but variation is restricted to alleles present in the parents. The number of polymorphic markers among five progenies of same cross was 172 and 133 with genomic SSR primers and EST-SSR primers respectively. The average number of polymorphic markers produced among 4 progenies of same cross by genomic primers was 217 whereas EST-SSR markers recorded a mean of 174.5 polymorphic markers. For 3 progenies of a same cross, polymorphic markers recorded by genomic SSR primers and EST-SSR primers were 128 and 81, respectively. The average of polymorphic markers generated by genomic and ESR SSR primers among two progenies of a same cross was 107.7 and 75.8, respectively. This clearly demonstrated that genomic SSR primers had more discriminating power by generating more number of polymorphic markers among the progenies sharing common gene pool compared to EST-SSR.

Polymorphism Information Content (PIC)

The polymorphisms produced by genomic SSR and EST-SSR primers were 99.73 and 99.48%, respectively. All SSR primer pairs produced 100% polymorphism except SCB 243, NKS 33 and SCB 208 which showed 66.66, 90 and 91.66% of polymorphism, respectively. High percentage of polymorphism among sugarcane genotypes were also reported by Devarumath et al. (2012), Chen et al. (2009) and Govindaraj et al. (2013). High percentage of polymorphism obtained by both genomic SSR and EST-SSR demonstrated that they can be useful in sugarcane genetic studies and germplasm characterization. Among 50 SSR primers (both genomic SSR and EST-SSR), PIC values ranged from 0.43 (SCB243) to 0.86 (SMC1604SA), with an average of 0.67 (Table 3). Genomic SSR markers showed moderately high PIC values than the EST-SSR markers. The PIC values of genomic SSR primers ranged from 0.50 (NKS 17) to 0.86 (SMC486CG) with a mean of 0.72, while moderate PIC values observed with EST-SSR primers which ranged from 0.43 (NKS 3) to 0.86 (SCB 486) with a mean of 0.62. Due to the high discrimination power and high polymorphism, genomic SSR primers can be used effectively in constructing genetic linkage maps and parental identification. EST–SSR markers had been reported to be moderately polymorphic when compared with genomic SSRs because of DNA sequences were more conserved in transcribed regions (Cho et al. 2000; Cordeiro et al. 2001; Filho et al. 2010). Pinto et al. (2006) reported higher PIC value of 0.82 with genomic SSR primers compared to 0.73 generated by EST-SSR primers with 13 commercial clones of sugarcane, three Saccharum species clones (S. officinarum, S. barberi and S. sinense) and the parents (SP80-180 and SP80-4966). High variation for the PIC values from 0.12 (Singh et al. 2013) to 0.96 (dos Santos et al. 2012) were reported depending upon the type of SSRs used and the genetic nature of the genotypes analysed. You et al. (2016) reported very high PIC values of 0.94 (genomic SSR) and 0.93 (EST-SSR) obtained using 181 sugarcane clones with 15 SSR primers.

Table 3.

Amplification pattern of 59 sugarcane genotypes generatged by 50 SSR primers

| S. No | Primer name | PIC | Polymorphism % | Size range (bp) | No. of markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCM7 | 0.6054 | 100 | 151–297 | 9 |

| 2 | SCM18 | 0.6039 | 100 | 239–523 | 14 |

| 3 | NKS3 | 0.4351 | 100 | 196–340 | 4 |

| 4 | NKS2 | 0.6428 | 100 | 178–488 | 10 |

| 5 | NKS1 | 0.6251 | 100 | 212–513 | 10 |

| 6 | SCB190 | 0.7047 | 100 | 126–725 | 17 |

| 7 | SCB208 | 0.5522 | 91.66 | 103–326 | 12 |

| 8 | SCB243 | 0.5275 | 66.66 | 170–306 | 3 |

| 9 | SCB246 | 0.5722 | 100 | 105–154 | 6 |

| 10 | SCB254 | 0.7115 | 100 | 106–204 | 12 |

| 11 | SCB486 | 0.8615 | 100 | 100–409 | 19 |

| 12 | SCB484 | 0.6992 | 100 | 100–461 | 15 |

| 13 | SCB474 | 0.6411 | 100 | 118–334 | 12 |

| 14 | SCB457 | 0.6347 | 100 | 149–410 | 11 |

| 15 | SCB441 | 0.5240 | 100 | 124–442 | 10 |

| 16 | SCB429 | 0.6664 | 100 | 117–487 | 23 |

| 17 | SCB378 | 0.4565 | 100 | 113–492 | 14 |

| 18 | SCB371 | 0.5999 | 100 | 107–428 | 25 |

| 19 | SCB370 | 0.6019 | 100 | 153–523 | 22 |

| 20 | SCB365 | 0.6064 | 100 | 117–603 | 31 |

| 21 | SCB271 | 0.6630 | 100 | 124–622 | 19 |

| 22 | UGSM36 | 0.5592 | 100 | 101–540 | 11 |

| 23 | UGSM49 | 0.6448 | 100 | 290–717 | 13 |

| 24 | UGSM141 | 0.6636 | 100 | 263–729 | 10 |

| 25 | UGSM193 | 0.7586 | 100 | 105–811 | 18 |

| 26 | SMC1604SA | 0.6978 | 100 | 120–239 | 10 |

| 27 | SMC336BS | 0.7778 | 100 | 122–547 | 25 |

| 28 | MSSCIR66 | 0.8043 | 100 | 175–339 | 20 |

| 29 | SMC703BS | 0.6385 | 100 | 198–569 | 15 |

| 30 | SMC278CS | 0.6778 | 100 | 112–540 | 16 |

| 31 | SMC31CUQ | 0.6384 | 100 | 147–428 | 12 |

| 32 | SMC569CS | 0.6286 | 100 | 134–659 | 13 |

| 33 | SMC486CG | 0.8620 | 100 | 105–400 | 22 |

| 34 | MSSCIR43 | 0.8123 | 100 | 179–583 | 23 |

| 35 | MSSCIR4 | 0.6508 | 100 | 237–624 | 17 |

| 36 | MSSCIR1 | 0.7271 | 100 | 100–655 | 17 |

| 37 | NKS56 | 0.5709 | 100 | 159–281 | 6 |

| 38 | NKS52 | 0.8472 | 100 | 123–252 | 14 |

| 39 | NKS51 | 0.8508 | 100 | 136–360 | 20 |

| 40 | NKS50 | 0.6460 | 100 | 103–697 | 21 |

| 41 | NKS48 | 0.6746 | 100 | 148–314 | 12 |

| 42 | NKS46 | 0.7232 | 100 | 122–314 | 8 |

| 43 | NKS45 | 0.6944 | 100 | 131–378 | 16 |

| 44 | NKS42 | 0.8285 | 100 | 143–373 | 22 |

| 45 | NKS33 | 0.8448 | 90 | 108–685 | 10 |

| 46 | NKS32 | 0.7654 | 100 | 155–418 | 10 |

| 47 | NKS7 | 0.7996 | 100 | 224–390 | 7 |

| 48 | NKS8 | 0.7896 | 100 | 183–384 | 7 |

| 49 | NKS11 | 0.7095 | 100 | 134–639 | 16 |

| 50 | NKS17 | 0.5064 | 100 | 217–607 | 15 |

| Overall mean | 0.674 | 99.58 | 14.48 |

Cluster analysis

Selection of parents in sugarcane is of paramount important as generation of variability is restricted to one recombination during hybridization and no scope for segregation in further clonal selection stages. Although morphological and agronomical traits were used in parental selection, recently DNA marker based diversity analysis and clustering were used for identification of diverse parents. In sugarcane, both genomic SSR (Cordeiro et al. 2000; Pan 2006) and EST-SSR (Filho et al. 2010; Marconi et al. 2011) based genetic diversity were reported. However, efficacies of genomic SSR and EST-SSR in grouping of genotypes were not studied in detail in sugarcane.

Genetic similarity co-efficient

Genetic similarity (GS) and dendrogram based on the genomic SSR or EST-SSR marker data were separately worked out. GS based on Jaccard’s coefficient was calculated with 373 polymorphic markers amplified by 25 genomic SSRs. GS values varied from 0.459 (BM 09283 and BM 10209) to 0.949 (BM 09285 and BM 09282) with the average value of 0.631. The highest GS between BM 09282 and BM 09285 was due to common Erianthus parents. The GS values estimated with these genomic SSR markers were comparable to the GS reported in sugarcane elsewhere (Chen et al. 2009; Saravanakumar et al. 2014). Average GS among the clones obtained from 348 polymorphic markers generated by 25 EST-SSR markers was 0.70. The most genetically dissimilar clones were BM 10195 and BM 09283 (0.451) with very low GS value between them. Singh et al. (2015) reported the GS which ranged from 0.47 to 0.91 using 48 EST-SSR markers in 26 commercial varieties of sugarcane while Alwala et al. (2006) reported a moderate GS of 0.68 with TRAP markers. The high mean GS values obtained by both genomic SSR (0.63) and EST-SSR (0.70) reveal the narrow genetic base of the clones which share common parents in their pedigree (Table 1). It also indicated that genomic SSR with low mean GS values had relatively higher discriminating power to identify even closely related clones compared to the EST SSR.

The binary data of 721 polymorphic markers generated by 50 SSR (genomic and EST) primers were used to generate combined dendrogram and genetic diversity analysis. Jaccard’s similarity coefficient between the pairs ranged from 0.466 (BM 09283 and BM 10218) to 0.954 (BM 09282 and BM 09285) with a mean of 0.665. The mean similarity co-efficient was the highest with the clone BM 09293 (0.688) followed by BM 09294 (0.687). The lowest mean similarity co-efficiency was recorded by BM 09283 with the value of 0.534 followed by 013102 (0.611). The clones with low mean GS can be crossed with an array of parents for generating more variability and selecting elite progenies with wider genetic base.

Comparison of GS assessed with genomic SSR and EST-SSR among the progenies of same cross

The average GS detected by genomic SSR between two progenies of the cross was 0.7 whereas EST-SSR detected the average GS of 0.78. Average GS detected by genomic SSR and EST-SSR markers among three progenies of a same cross was 0.76 and 0.84, respectively. The average GS detected among 4 progenies of a same cross by genomic SSR and EST-SSR markers was 0.66 and 0.70, respectively. Likewise, genomic SSR and EST-SSR detected the average GS among five progenies of a same cross was 0.76 and 0.8, respectively. These results suggested that genomic SSR which recorded low mean GS could be used for discriminating the progenies sharing common parents.

Efficiency of genomic and EST SSR in grouping of genotypes

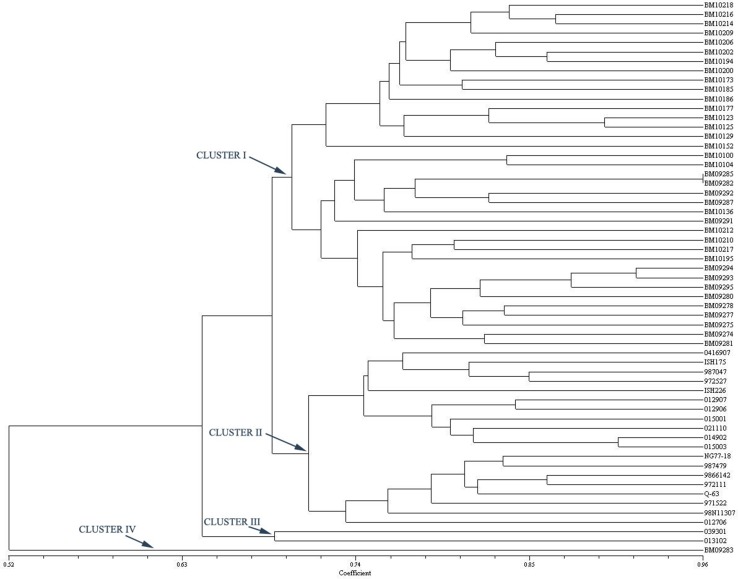

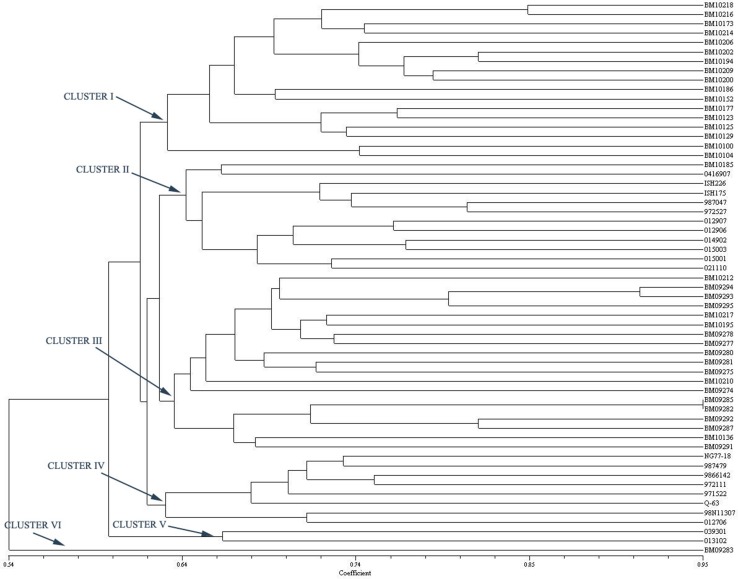

The 59 sugarcane accessions were grouped into six and four clusters using genomic SSR and EST-SSR, respectively. The difference in number of groups formed might be due to the variation in number of markers produced by genomic SSR and EST-SSR and different portion of genome amplified by both markers (Hu et al. 2011). In EST-SSR based dendrogram (Fig. 1), most of the high biomass clones were clustered together in Cluster I while these clones were grouped into Clusters I and III with genomic SSRs (Fig. 2). Differences in the distribution of some genotypes were observed in the phylogenetic trees constructed by different markers. BM 10210 and BM 10217, the progenies of Erianthus X Commercial Cane, were found in different clusters in genomic SSR tree but the genotypes were clustered together with EST-SSR tree. Another pair of genotypes, viz., BM10173 and BM 10185 which shared ISH 100 as one of their parents clustered together (Cluster I) in EST-SSR tree, but they were distantly clustered with genomic SSR. BM09274 and BM0981 which had common parent (013502) clustered together in EST-SSR dendrogram Cluster I but these both clones were differently clustered in genomic SSR tree. The differences observed between the two trees using different marker systems could be due to the differences in targeted DNA regions or genomic coverage rate of the different marker systems (Varshney et al. 2005). BM 10177 and BM 09281 which were the progenies of a same cross (038701 × Co 62198) were clustered in different cluster in genomic SSR dendrogram, whereas the above said clones were clustered in a same cluster in EST-SSR dendrogram. The results clearly demonstrated that the genomic SSR with higher PIC and lower GS values could identify even minor genetic differences between the genotypes and group them accordingly.

Fig. 1.

Dendrogram based on the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and UPGMA clustering method using EST–SSR primers

Fig. 2.

Dendrogram based on the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and UPGMA clustering method using genomic SSR primers

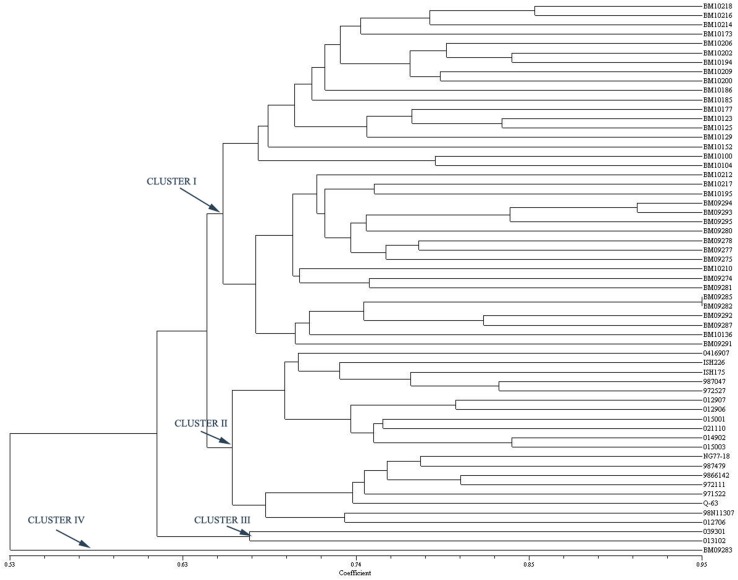

A dendrogram was constructed combining both genomic SSR and EST-SSR marker data (Singh et al. 2011; You et al. 2016) using UPGMA method (Fig. 3). Using the average similarity, clustering divided the sugarcane accessions into four clusters. Cluster I comprised of 37 clones, which were the clones with high biomass content. Cluster II consisted of 19 near commercial hybrids, S. officinarum clone and Inter Specific Hybrids (ISH). Cluster III grouped 2 genotypes while Cluster IV had single genotype with Erianthus arundinaceus in the immediate pedigree. The clustering pattern of combined primers was mostly resembling the EST SSR based grouping of genotypes. Considering the agronomic performance of the clones, in all the three types of dendrograms (genomic SSR, EST SSR and combined SSR), the clone BM 09283 with low juice brix % was clustered separately. Except BM10173 all the low fibre content clones were clustered together in EST-SSR dendrogram and combined dendrogram. These results suggested that both markers system (genomic SSR and EST-SSR) can be efficiently used for unraveling the genetic variability in sugarcane. In particular, genomic SSR can be used for broad based grouping of genotypes efficiently; however, EST SSR based clustering may be more efficient in identification of diverse parents for crossing programmes because the GS is estimated with the functional markers related to the genes.

Fig. 3.

Dendrogram based on the Jaccard’s similarity coefficient and UPGMA clustering method using both EST-SSR and Genomic SSR primers

Conclusion

Genomic SSR and EST-SSR were compared for their efficiency in different molecular marker analysis based on the markers generated with 59 clones. The result indicated that genomic SSR showed higher polymorphism and PIC compared to EST-SSR. Genetic diversity among 59 sugarcane accessions was well resolved by both EST-SSR and genomic SSR in grouping them into distinct clusters. Higher number of clusters formed by genomic SSR indicated that subgrouping of genotypes could be possible by estimating the minor genetic differences among the genotypes. High level of PIC and low genetic similarity values of genomic SSR may be more useful in DNA fingerprinting, selection of true hybrids, identification of variety specific markers and genetic diversity analysis. Identification of diverse parents in breeding programmes based on cluster analysis of genotypes can be effectively done with EST-SSR as the genetic similarity was estimated based on functional attributes related to morphological/agronomical traits.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Indian Council of Agricultural Research and the Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore for the funding and infrastructure.

Author contributions

Dr. P. Govindaraj designed the research, instrumental in conception of the work, provided a critical review of the article and valuable suggestions in the interpretation of data. Mr. S. Parthiban performed the lab and field experiments, analyzed the results and drafted the manuscript. Mr. S. Senthilkumar helped in field and lab experiments.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1172-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Ahmad A, Wang JD, Pan YB, Deng ZH, Chen ZW, Chen RK, Gao SJ. Molecular identification and genetic diversity analysis of Chinese sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrids) varieties using SSR markers. Trop Plant Biol. 2017;10:194. doi: 10.1007/s12042-017-9195-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed MS, Gardezi SDA. Molecular characterization of locally adopted sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum L.) varieties using microsatellite markers. The J Anim. Plant Sci. 2017;27(1):164–174. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov NN, Brover VV, Freidin S, Troukhan ME, Tatarinova TV, Zhang H, Swaller TJ, Lu YP, Bouck J, Flavell RB, Feldmann KA. Insights into corn genes derived from large-scale cDNA sequencing. Plant Mol Biol. 2009;69:179–194. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9415-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwala S, Suman A, Arro JA, Veremis JC, Kimbeng CA. Target region amplification polymorphism (TRAP) for assessing genetic diversity in sugarcane germplasm collections. Crop Sci. 2006;46:448–455. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2005.0274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JA, Churchill GA, Sutrique JE, Tanksley SD, Sorrells ME. Optimizing parental selection for genetic linkage maps. Genome. 1993;36:181–186. doi: 10.1139/g93-024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andru S, Pan YB, Thongthawee S, Burner DM, Kimbeng CA. Genetic analysis of the sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) cultivar ‘LCP 85-384’.I. Linkage mapping using AFLP, SSR, and TRAP markers. Theor Appl Genet. 2011;123:77–93. doi: 10.1007/s00122-011-1568-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasileiro BP, Marinho CD, Costa PMA, Moreira EFA, Peternelli LA, Barbosa MHP. Genetic diversity in sugarcane varieties in Brazil based on the Ward-Modified Location Model clustering strategy. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(1):1650–1660. doi: 10.4238/2014.January.17.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DL, Botha FC. Preliminary analysis of expressed sequence tags for sugarcane. Crop Sci. 2000;40:1769–1779. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2000.4061769x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carson DL, Huckett BI, Botha FC, van Staden J. Differential gene expression in sugarcane leaf and internodal tissues of varying maturity. S Afr J Bot. 2002;68(4):434–442. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6299(15)30370-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casu R, Dimmock C, Thomas M, Bower N, Knight D, Grof C. Genetic and expression profiling in sugarcane. Proc Int Soc Sugarcane Technol. 2001;24:626–627. [Google Scholar]

- Chen PH, Pan YB, Chen RK, Xu LP, Chen YQ. SSR marker-based analysis of genetic relatedness among sugarcane cultivars (Saccharum spp. hybrids) from breeding programs in China and other countries. Sugar Tech. 2009;11(4):347–354. doi: 10.1007/s12355-009-0060-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YG, Ishii T, Temnykh S, Chen X, Lipovich L, McCouch SR, Park WD, Ayres N, Cartinhour S. Diversity of microsatellites derived from genomic libraries and GenBank sequences in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2000;100:713–722. doi: 10.1007/s001220051343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro GM, Taylor GO, Henry RJ. Characterization of microsatellite markers from sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) a highly polyploidy species. Plant Sci. 2000;155:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(00)00208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro GM, Casu R, McIntyre CL, Manners JM, Henry RJ. Microsatellite markers from sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) ESTs cross transferable to Erianthus and Sorghum. Plant Sci. 2001;160:1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00365-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeiro GM, Pan YB, Henry RJ. Sugarcane microsatellites for the assessment of genetic diversity in sugarcane germplasm. Plant Sci. 2003;165:181–189. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00157-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devarumath RM, Kalwade SB, Kawar PG, Sushir KV. Assessment of genetic diversity in sugarcane germplasm using ISSR and SSR markers. Sugar Tech. 2012;14(4):334–344. doi: 10.1007/s12355-012-0168-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos JM, Filho LSCD, Soriano ML, da Silva PP, Nascimento VX, de Souza Barbosa GV, Todaro AR, Neto CER, Almeida C. Genetic diversity of the main progenitors of sugarcane from the RIDESA germplasm bank using SSR markers. Ind Crops Prod. 2012;40:145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Filho LSDG, Silva PP, Santos JM, Barbosa GVS, Ramalho-Neto CE, Soares L, Andrade JCF, Almeida C. Genetic similarity among genotypes of sugarcane estimated by SSR and coefficient of parentage. Sugar Tech. 2010;12(2):145–149. doi: 10.1007/s12355-010-0028-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaraj P, Balasundaram N, Sharma TR, Bansal KC, Koundal KR, Singh NK (2005) Development of new STMS markers for sugarcane. Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, TamilNadu, India. http://www.nrcpb.org/content/development-new-stms-markers-sugarcane. Accessed 25 July, 2009

- Govindaraj P, Sindhu P, Appunu C, Parthiban S, Senthilkumar S. Genetic diversity analysis among interspecific and intergeneric hybrids of Saccharum spp. using STMS markers. Res Crops. 2013;14(3):915–920. [Google Scholar]

- Grivet L, Arruda P. Sugarcane genomics: depicting the complex genome of an important tropical crop. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;5:122–127. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Wang L, Li J. Comparison of genomic SSR and EST-SSR markers for estimating genetic diversity in cucumber. Biol Plantarum. 2011;55(3):577–580. doi: 10.1007/s10535-011-0129-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalwade SB, Devarumath RM. Single strand conformation polymorphism of genomic and EST-SSRs marker and its utility in genetic evaluation of sugarcane. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2014;20(3):313–321. doi: 10.1007/s12298-014-0231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Nakamura Y, Sasaki E, Kyozuka J, Fukuda H, Sawa S. Gain-of-function phenotypes of chemically synthetic CLAVATA3/ESR-related (CLE) peptides in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007;48(12):1821–1825. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Kaul S, Rounsley S, Shea TP, Benito MI, Town CD, Fujii CY, Mason T, Bowman CL, Barnstead M, Feldblyum TV, Buell CR, Ketchum KA, Lee J, Ronning CM, Koo HL, Moffat KS, Cronin LA, Shen M, Pai G, Aken SV, Umayam L, Tallon LJ, Gill JE, Adams MD, Carrera AJ, Creasy TH, Goodman HM, Somerville CR, Copenhaver GP, Preuss D, Nierman WC, White O, Eisen JA, Salzberg SL, Fraser CM, Venter JC. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;16:761–768. doi: 10.1038/45471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xu W, Tan L, Xue Y, Sun C, Su Z. Case study for identification of potentially indel-caused alternative expression isoforms in the rice subspecies japonica and indica by integrative genome analysis. Genomics. 2008;91(2):186–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi GT, Costa EA, Miranda HRCAN, Mancini MC, Silva CBC, Oliveira KM, Pinto LR, Mollinari M, Garcia AAF, Souza AP. Functional markers for gene mapping and genetic diversity studies in sugarcane. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:264. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira KM, Pinto LR, Marconi TG, Margarido GRA, Pastina MM, Teixeira LHM. Functional integrated genetic linkage map based on EST markers for a sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) commercial cross. Mol Breed. 2007;20:189–208. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9082-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira KM, Pinto LR, Marconi TG, Mollinari M, Ulian EC, Chabregas SM, Falco MC, Burnquist W, Garcia AAF, Souza AP. Characterization of new polymorphic functional markers for sugarcane. Genome. 2009;52:191–209. doi: 10.1139/G08-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan YB. Highly polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers for sugarcane germplasm evaluation and variety identity testing. Sugar Tech. 2006;8:246–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02943564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pashley CH, Ellis JR, McCauley DE, Burke JM. EST database as a source for molecular markers: lessons from Helianthus. J Hered. 2006;97:381–388. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera MF, Arias ME, Costilla D, Luque AC, Garcia MB, Romero CD, Racedo J, Ostengo S, Filippone MP, Cuenya MI, Castagnaro AP. Genetic diversity assessment and genotype identification in sugarcane based on DNA markers and morphological traits. Euphytica. 2012;185:491–510. doi: 10.1007/s10681-012-0661-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LR, Oliveira KM, Marconi T, Garcia AAF, Ulian EC. Characterization of novel sugarcane expressed sequence tag microsatellites and their comparison with genomic SSRs. Plant Breed. 2006;125:378–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2006.01227.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piperidis N, Jackson PA, D’Hont A, Besse P, Hoarau JY, Courtois B, Aitken KS, McIntyre CL. Comparative genetics in sugarcane enables structured map enhancement and validation of marker-trait associations. Mol Breed. 2008;21:233–247. doi: 10.1007/s11032-007-9124-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raboin LM, Oliveira KM, Lecunff L, Telismart H, Roques D, Butterfield M, Hoarau JY, D‘Hont A. Genetic mapping in sugarcane, a high polyploid, using bi-parental progeny: identification of a gene controlling stalk colour and a new rust resistance gene TAG. Theor Appl Genet. 2006;112:1382–1391. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racedo J, Gutiérrez L, Perera MF, Ostengo S, Pardo EM, Cuenya MI, Welin B, Castagnaro AP. Genome-wide association mapping of quantitative traits in a breeding population of sugarcane. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16:142. doi: 10.1186/s12870-016-0829-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach BT. Nobilization sugarcane. Proc Int Soc Sugarcane Technol. 1972;14:206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Saravanakumar K, Govindaraj P, Appunu C, Senthilkumar S, Kumar Ravinder. Analysis of genetic diversity in high biomass producing sugarcane hybrids (Saccharum spp. complex) using RAPD and STMS markers. Indian J Biotechnol. 2014;13:214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Srivastava S, Singh SP, Sharma ML, Mohapatra T, Singh NK, Singh SB. Identification of new microsatellite DNA markers for sugar and related traits in sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2008;10(4):327–333. doi: 10.1007/s12355-008-0058-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Singh RB, Singh SP, Sharma ML. Identification of sugarcane microsatellites associated to sugar content in sugarcane and transferability to other cereal genomes. Euphytica. 2011;182:335–354. doi: 10.1007/s10681-011-0484-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RK, Jena SN, Khan S, Yadav S, Banarjee N, Raghuvanshi D, Bhardwaj V, Dattamajumder SK, Kapur R, Solomon S, Swapna M, Srivastava S, Tyagi AK. Development, cross-species/genera transferability of novel EST-SSR markers and their utility in revealing population structure and genetic diversity in sugarcane. Gene. 2013;524:309–329. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.03.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RB, Singh B, Singh RK. Development of microsatellite (SSRs) markers and evaluation of genetic variability within sugarcane commercial varieties (Saccharum spp. hybrids) Int J Adv Res. 2015;3(12):700–708. [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Singh SP, Tiwari AK, Sharma BL. Genetic diversity of sugarcane hybrid cultivars by RAPD markers. 3 Biotech. 2017;7:222. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0855-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund C, Descour A, Kudrna D, Bomhoff M, Boyd L, Currie J, Angelova A, Collura K, Wissotski M, Ashley E, Morrow D, Fernandes J, Walbot V, Yu Y. Sequencing, mapping, and analysis of 27,455 maize full-length cDNAs. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(11):e1000740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tew TL, Pan Y. Microsatellite (SSR) Marker-based paternity analysis of a seven-parent poly crosses in sugarcane. Crop Sci. 2010;50:1401–1408. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.10.0579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varshney RK, Graner A, Sorrells MW. Genic microsatellite markers in plants: features and applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen MF, Wang HY, Xia ZQ, Zou ML, Lu C, Wang WQ. Development of EST-SSR and genomic-SSR markers to assess genetic diversity in Jatropha curcas L. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:42–50. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz A, Nishiyama MY, Fuentes BG, Souza GM, Janies D, Gray J, Grotewold E. GRASSIUS: a Platform for comparative regulatory genomics across the grasses. Plant Physiol. 2009;149(1):171–180. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You Q, Pan YB, Xu LP, Gao SW, Wang QN, Su YC, Yang YQ, Wu QB, Zhou DG, Que YX. Genetic diversity analysis of sugarcane germplasm based on fluorescence-labeled simple sequence repeat markers and a capillary electrophoresis-based genotyping platform. Sugar Tech. 2016;18(4):380–390. doi: 10.1007/s12355-015-0395-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.