Abstract

Objective

The object of this study was to explore the use of complementary health approaches among U.S. adults with a cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years and distinguish use for general wellness from use specifically for treatment.

Methods

Using data from the 2002, 2007, and 2012 National Health Interview Survey, the study included 1359 persons with a cancer diagnosis of selected cancers in the past 5 years. Participants were asked about their use of complementary health approaches for general reasons and cancer treatment in the past 12 months. Responses were aggregated into the use of any complementary approach as well as examined by mode of practice.

Results

Overall, 35.3% of persons with a cancer diagnosis used complementary health approaches in the past 12 months. These persons were more likely to have used a biologically based approach (22.8%) compared with other approaches. Persons with breast cancer were significantly more likely to use any complementary health approach (43.6%) compared with those with other recently diagnosed cancers. Few persons with a cancer history (2.3%) used complementary approaches specifically for cancer treatment. However, prevalence of use for treatment varied by cancer type (0.4%–6.8%).

Conclusions

This study highlights differences in the use of various types of complementary health approaches for different reasons among persons with recent diagnoses of some of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States.

Keywords: cancer, CAM, herbal, mind/body

Introduction

According to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, ~39.6% of men and women will be diagnosed with some form of cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2008–2010 data.1 To date, there are over 14 million cancer survivors in the United States (U.S.), 5.5 million of whom have had a cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years. Therapeutic practices not considered a part of mainstream western medicine (complementary health approaches), have long been used in cancer treatment; however, research on the use of these approaches are usually therapy specific,2,3 cancer specific,2,4 or limited to clinical trials.2,4,5

Currently, few studies provide a national estimate of use of the different groups of complementary health approaches for wellness and/or treatment by persons with a recent cancer diagnosis. Some studies have examined the collective use of complementary health approaches among survivors;6 use of specific approaches;7,8 or general use among specific cancer populations.9,10 It is known that compared with persons without a previous cancer diagnosis, those with a cancer history are more likely to use complementary health approaches to enhance their immune system, for general disease prevention, and to manage their pain.11

In adding to current literature, this report looks at specific groups of complementary health approaches, at five of the most frequently diagnosed cancers and at use for treatment as distinct from use for wellness. While some cancer centers provide integrative oncology services offering complementary health approaches in conjunction with conventional therapies,12,13 many do not. In trying to gain some control over their health, some persons with a recent cancer diagnosis may use complementary health approaches, but may not always inform their cancer care providers.14,15 This study sought to examine what subgroups of complementary health approaches are most pursued among U.S. adults with a diagnosis of specific cancers within the past 5 years, and for what reasons.

Methods

Data source

Data from the 2002, 2007, and 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) were used for this analysis.16-18 The NHIS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional household interview survey that is fielded continuously by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and produces annual estimates of the health of the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population. Interviews are conducted in respondents’ homes. Health and sociodemographic information is collected on each member of all families residing within a sampled household. Within each family, additional information is collected from one randomly selected adult (the “sample adult”) aged 18 years or older.

This study was based on a combined sample of 88,962 adults. Information on cancer history was obtained from the Sample Adult file, while the information on the use of complementary health approaches in the past 12 months was collected from adults who participated in the Adult Alternative Medicine supplements. The sample size and response rates of the annual NHIS varied across supplements; in 2012, 34,525 adults completed interviews, with an overall response rate of 61.2%. In 2007, 23,393 adults completed interviews, yielding an overall response rate of 67.8%. With 31,044 adults completing the NHIS interview in 2002, the overall response rate was 74.3%. Procedures used in calculating response rates are described in detail in Appendix I of the NHIS Survey Description document for the respective years.16-18

Sample adults who responded “Yes” to “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” were defined as having a cancer diagnosis (n = 7165). Participants were then asked what kind of cancer it was and how old they were when first diagnosed? In this study, we examined U.S. adults with a diagnosis within 5 years of their interview (n = 1228) for five of the most commonly diagnosed cancers: bladder (n =71), breast (n =477), colorectal (n =222), lung (n = 129), and prostate cancers (n = 351). The sum of individual cancers may be greater than the total number of persons diagnosed within the past five years, as the NHIS allows participants to mention having up to three kinds of cancers. Time since diagnosis (5 years or less) was calculated by subtracting the age at diagnosis from the age at interview (current age).

Complementary health approaches encompass a wide range of modalities. More than 95% of study participants with a diagnosis of each of the aforementioned cancers responded to questions about the use of named complementary health approaches in the past 12 months (n = 1205). Those who responded yes to ever using a complementary health approach were asked about the general use of complementary health approaches and for what health problems, symptoms, or conditions their top three or most frequently used approaches were used for cancer treatment. Information on use of each type of approach was collected on an individual basis. Only approaches that were consistent across all three surveys were included in this study. Participants could use more than one approach as well as use different approaches for different reasons. Participants with missing information on use of these approaches were excluded from analyses. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between persons with a recent cancer diagnosis and use of complementary health approaches. Use of mainstream or conventional medicine among participants was not assessed.

FIG. 1.

Venn diagram showing the relationship between persons with a recent cancer diagnosis and the use of complementary health approaches; National Health Interview Survey 2002, 2007, 2012.

Statistical analyses

Responses were analyzed by their mode of practice: biologically based (nonvitamin and nonmineral dietary supplements, vitamins, special diets, and chelation), manipulative, and body based (chiropractic or osteopathic manipulation, and massage), mind and body approaches (biofeedback, energy healing therapy, guided imagery, hypnosis, meditation, progressive relaxation, tai chi, qi gong, and yoga), and whole medical systems (Ayurveda, acupuncture, homeopathy, and naturopathy). Estimates in this report were calculated using the sample adult sampling weight and are representative of the noninstitutionalized population of U.S. adults aged 18 years and older. Data weighting procedures are described in more detail elsewhere.19,20

Point estimates, and estimates of their variances, were calculated using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.0,21 which accounts for the complex sample design of the NHIS. Unless otherwise specified, the denominator used was all adults aged 18 years and older with a cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years. Calculations excluded persons with unknown information regarding cancer history and the use of complementary health approaches. Due to small sample size, some estimates may be unreliable.

Due to the small sample size of subpopulations of persons with a cancer diagnosis in the annual survey, data for analyses were pooled over several years. However, preliminary analyses of data demonstrated no significant difference in the use of complementary health approaches among these persons between the 3 data years (2002, 2007, and 2012) used in this study.

Results

Study sample

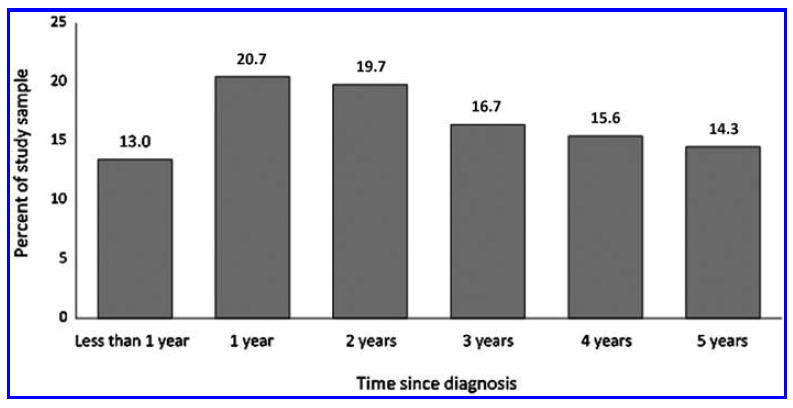

Thirteen percent of participants were diagnosed with cancer within 1 year before the NHIS interview. Almost one half of participants (40.4%) had their first cancer diagnosis more than 1 year, but less than 3 years before their interview. The remaining participants (46.6%) were diagnosed with cancer 3–5 years before their interview (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Length of time since first cancer diagnosis. Time since diagnosis was calculated by subtracting each participant’s age at diagnosis from their age at the time of NHIS interview. Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2002, 2007, 2012.

General use of complementary health approaches

The study sample represented more than 5 million persons with a cancer diagnosis. In general, 35.3% of these persons used a complementary health approach in the past 12 months. More persons with a recent cancer diagnosis used a biologically based approach (22.8%) in the past 12 months compared with mind and body approaches (14.9%), manipulative and body-based approaches (14.2%), and whole medical systems (3.7%) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Use of complementary health approaches among persons with a recent cancer diagnosis. (1) Significantly different from mind and body approaches, p < 0.05. (2) Significantly different from manipulative and body-based approaches, p < 0.05. (3) Significantly different from whole medical systems, p < 0.05. General use of complementary health approaches for any reason during the past 12 months. Use for treatment specifically to treat cancer and related problems, symptoms. The denominators are U.S. adults aged 18 and over with a cancer diagnosis within 5 years of their interview. Source: CDC/NCHS, National Health Interview Survey, 2002, 2007, 2012.

More than 4 in 10 persons with a breast cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach; however, there was no significant difference in the use of biologically based (24.9%) and mind and body approaches (26.2%). These persons were significantly less likely to use manipulative and body-based approaches (17.0%) compared with mind and body approaches, and less likely to use whole medical systems (6.1%) compared with all other approaches. Almost one in three persons with a prostate cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach. Use of biologically based approaches was almost twice as high as manipulative and body-based approaches and more than twice that of mind and body approaches (Table 1).

Table 1.

General Use of Complementary Health Approaches Within the Past 12 Months Among Persons with a Cancer Diagnosis in the Past 5 Years: National Health Interview Survey 2002, 2007, 2012

| Primary cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years, Percent% (standard error)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All survivors | Bladder | Breast | Colorectal | Lung | Prostate | |

| Any complementary health approach | 35.3 (0.99) | 30.1 (5.86) | 43.6 (2.44) | 30.1 (3.36) | 32.4 (9.1) | 30.8 (2.66) |

| Biologically based approaches | 22.8 (0.92) | 23.5 (5.39) | 24.9 (2.24) | 19.5 (2.88) | 17.3 (4.03) | 22.7 (2.59) |

| Mind and body approaches | 14.9 (0.82) | * | 26.2 (2.11) | 9.8 (2.23) | 14.3 (0.87) | 10.1 (2.09) |

| Manipulative and body-based approaches | 14.2 (0.78) | *6.6 (3.26) | 17.0 (1.96) | 13.6 (2.70) | 16.7 (4.10) | 12.3 (2.20) |

| Whole medical systems | 3.7 (0.47) | * | 6.1 (1.65) | 4.8 (1.67) | * | *4.1 (1.54) |

Estimates are considered unreliable. Data preceded by an asterisk have a relative standard error (RSE) greater than 30% and less than or equal to 50%, and should be used with caution. Data not shown have an RSE greater than 50%.

Almost one third of persons with a history of colorectal cancer used any complementary health approach; these persons were more than twice as likely to use biologically based approaches compared with mind and body approaches (19.5% vs. 9.8%) and almost four times as likely compared with whole medical systems (4.8%). Almost one third of persons with a lung cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach. There were no statistically significant differences in the general use of biologically based, mind and body, or manipulative and body-based approaches among these persons.

Persons with a history of bladder cancer were almost four times as likely to use biologically based approaches compared with manipulative and body-based approaches.

Use of complementary health approaches for treatment

Less than 5% of persons with a cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach for treatment of the disease. However, these persons were more likely to use biologically based (2.3%) and mind and body approaches (1.9%) compared with manipulative and body-based approaches (1.1%) and whole medical systems (0.5%) for cancer-related treatment (Fig. 3).

Six percent of persons with a breast cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach to treat their cancer. There was no statistically significant difference in the use of biologically based, mind and body, or manipulative and body-based approaches for cancer treatment among these persons. However, persons with a breast cancer diagnosis were less likely to use whole medical systems for treatment compared with all other approaches (Table 2).

Table 2.

Use of Complementary Health Approaches for Cancer Treatment Within the Past 12 Months, Among Persons with a Cancer Diagnosis in the Past 5 Years: National Health Interview Survey 2002, 2007, 2012

| Primary cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years, Percent% (standard error) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| All survivors | Breast | Colorectal | Lung | |

| Any complementary health approach | 3.3 (0.39) | 6.0 (1.17) | 6.1 (0.07) | 9.1 (0.88) |

| Biologically based approaches | 2.3 (0.32) | 3.6 (0.54) | 5.5 (0.06) | 3.3 (0.86) |

| Mind and body approaches | 1.9 (0.30) | 3.0 (0.50) | 3.0 (0.03) | 6.8 (0.87) |

| Manipulative and body-based approaches | 1.1 (0.23) | 2.5 (0.37) | 0.4 (0.00) | 5.1 (0.86) |

| Whole medical systems | 0.5 (0.13) | 0.9 (0.17) | 0.9 (0.01) | 3.0 (0.86) |

Just over 6% of persons with colorectal cancer diagnosis used any complementary health approach for treatment. Use of biologically based controls among these persons was significantly higher (5.5%) than mind and body (3.0%) and all other complementary health approaches. Although small, the use of whole medical systems for treatment (0.9%) was twice as high as manipulative and body-based approaches. Among persons with a lung cancer diagnosis, mind and body (6.8%) or manipulative and body-based approaches (5.1%) were more likely to be used for cancer treatment compared with biologically based approaches (3.3%) and whole medical systems (3.0%). Estimates on the use of complementary health approaches for treatment among persons with prostate and bladder cancer were unreliable and are not presented.

Discussion

Compared with the 1970s, cancer survivorship has quadrupled in 2016 at 15.5 million. This is due, in part, to advances in detection and treatment.22 With increased survivorship, significant changes have emerged in the healthcare needs of patients, their families, and caregivers as they learn to develop a “new normal” in living with a cancer diagnosis. At the initial or early stages of diagnosis, most persons with cancer are interested in any treatment that may help fight or cure the disease, even if these methods are not part of a routine standard of care.23 However, persons who have completed their cancer treatment often try to shift to or maintain a healthy lifestyle.24,25 This often includes the use of natural therapies such as vitamins and minerals or complementary health approaches.26

Survivorship is becoming an increasingly important oncology issue, particularly to those who have completed their cancer treatment. The loss of a systematic treatment plan often leaves persons who have completed their cancer treatment with little understanding or direction in planning to assist them along their survivorship continuum.27 Although the use of complementary health approaches among persons with a cancer history differed by type of approach and cancer type, we found that more than one in three persons with a cancer diagnosis in the past 5 years used a complementary health approach. Yet, this study revealed that very few persons with a diagnosis within the past 5 years used complementary health approaches specifically for cancer treatment. Ojukwu et al. found even higher rates of general use of complementary health approaches among overweight and obese cancer survivors (71%) compared with the general population.10 Notwithstanding, that study included persons with a previous cancer diagnosis, regardless of whether or not they had symptoms of cancer at the time of the survey, and did not investigate the use of complementary health approaches specifically for cancer treatment. The general use of complementary health approaches was significantly higher among persons with a cancer diagnosis, particularly those with breast cancer (43.6%), when compared with the general U.S. population (33.2%), as noted in previous research.28,29

Biologically based approaches were the most commonly used modalities, while whole medical systems were the least used for general use or cancer treatment compared with all other approaches. The popularity of biologically based approaches (including herbal supplements) may be because they are assumed to be safe, cause less complications, and are less likely to cause dependency.30

Among persons with a recent cancer diagnosis, those with breast cancer were the most likely to use complementary health approaches for general use; however, use for treatment was highest among persons with a lung cancer diagnosis. While most study participants used biologically based and mind and body approaches, persons with a lung cancer diagnosis also favored manipulative and body-based approaches. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among U.S. adults showed that women were almost one third more likely to use these approaches compared with men in 2002, 2007, and 2012.29,31 Women were also almost twice as likely to use mind and body approaches such as hypnosis, meditation, yoga, and prayer compared with men.31 This would explain the observed high use of complementary health approaches among breast cancer survivors, and underscores some of the more commonly used types of approaches. Using data from the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program for the period 2005–2009, Henley et al. found that lung cancer incidence was still significantly higher among men compared with women, despite a decrease in incidence during this period.32 Lung cancer is difficult to treat and persons with a lung cancer diagnosis may be more receptive to the use of complementary approaches potentially improving treatment outcomes by reducing adverse symptoms and mood disorders, and by enhancing declining function. Ladas and Kelly suggested that sometimes cancer patients may need other therapies in addition to conventional treatments such as corticosteroids and bronchodilators to aid with the shortness of breath that is generally associated with lung cancer.33 In our study, we found that persons with a lung cancer diagnosis were more likely to use mind and body approaches that include deep breathing, yoga, and other relaxation techniques for their disease treatment. Persons with a lung cancer diagnosis also used manipulative and body-based approaches such as massage therapy and chiropractic. It is evident that persons with a lung cancer diagnosis are more likely to use the more physical approaches for treatment, while biologically based approaches such as nonvitamin and nonmineral dietary supplements and special diets were more commonly used among persons with other cancer diagnoses. The high use of these approaches among persons with a lung cancer diagnosis highlights the need for further research to better understand how these modalities are incorporated into integrative cancer treatment.

Campo et al. suggested that the use of mind and body approaches differ by the stage of cancer survivorship (i.e., acute <1 year; short term 1–5 years; and long term >5 years since diagnosis).7 This is because each stage of survivorship presents varying intensities of medical treatment, activities, and effects, and involves different associated patient emotions. Their study showed that more acute survivors reported medical-related reasons for using mind and body approaches and more short-term survivors reported use to manage symptoms. Although this study population was too small to examine the reason for use of complementary health approaches by time since diagnosis more closely, it follows that with less than 15% of the population first diagnosed within 1 year of their interview, use for cancer treatment was low.

This study found that the use of more common complementary health approaches by persons with a recent cancer diagnosis was comparable to the general population; however, Gansler et al.26 noted an increased use in other forms of complementary health approaches. It is known that the exclusion of vitamin or mineral supplements from this study may lead to an underreporting of complementary health approaches when compared to studies that include these supplements in the group of biologically based approaches. As many as 81% of persons with cancer use vitamin or mineral supplements during and post-treatment.6,34 This is significantly higher than use among the general population.35,36

A major strength of these analyses is that the data are from a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, allowing for population estimates. The large sample size allows for estimation of the use of groups of complementary health approaches among U.S. cancer adults with a diagnosis of selected cancer types in the 5 years before their interview. However, the data in this report are not without limitations. NHIS is a cross-sectional survey, and causal associations cannot be made. The study sample of adults with a “Yes” response to “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” includes persons with cancer diagnosis, regardless of whether or not they had symptoms of cancer at the time of the survey. For this reason and because the data are limited to a diagnosis 5 years before the interview, we referred to study participants as persons with a recent cancer diagnosis.

We also note that although the study includes participants 18 years and older, it is possible a participant may have been diagnosed with a cancer before age 18.

Additionally, although a participant can mention up to three kinds of cancers, the NHIS self-reported data does not allow distinction between multiple primary cancers and carcinomatous metastasis. The NHIS also does not capture the reoccurrence of a specific type of cancer. For these reasons it is difficult to say with clinical certainty whether a participant truly had multiple types of cancer.

The data also preclude assumption of the general use of complementary health approaches before a cancer diagnosis and does not collect information on concurrent treatment by mainstream Western medicine. In addition, it was also not clear if respondents’ interpretation of use for treatment refers directly to treating the actual tumor or encompasses treatment of associated side-effects. The NHIS survey asks respondents about use of approaches for treatment of some side-effects associated with cancer, for example, nausea, but it does not specify nausea associated with cancer or cancer treatment. Responses are dependent on participants’ recall of complementary health approaches that they used in the past 12 months, as well as their willingness to report their use accurately.

Conclusions

This study highlights differences in the use of various types of complementary health approaches for different reasons among persons with a recent diagnosis of some of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in the United States. While the general use of complementary health approaches did not significantly differ from the general population, use of groups of approaches for cancer treatment varied by cancer type among persons with a diagnosis. Information presented in this study may be used in physician–patient dialogue about the use of complementary health approaches during cancer treatment. It may also serve as a foundation and guide for researchers with an interest in the use of individual complementary health approaches among persons with a recent cancer diagnosis.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement

The author has no relationships with pharmaceutical companies or products to disclose, nor are off-label or investigative products discussed in this study. All views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute. [August 1 2015];Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER) Stat Fact sheets: All Cancer Sites. Online document at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/all.html.

- 2.Danhauer SC, Mihalko SL, Russell GB, et al. Restorative yoga for women with breast cancer: Findings from a randomized pilot study. Psychooncology. 2009;18:360–368. doi: 10.1002/pon.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bower JE, Woolery A, Sternlieb B, Garet D. Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control. 2005;12:165. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.John GM, Hershman DL, Falci L, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among U.S. cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:850–864. doi: 10.1007/s11764-016-0530-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campo RA, Leniek KL, Gaylord-Scott N, et al. Weathering the seasons of cancer survivorship: Mind-body therapy use and reported reasons and outcomes by stages of cancer survivorship. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:3783–3791. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3200-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauche R, Wayne PM, Dobos G, et al. Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of t’ai chi and qigong use in the United States: Results of a nationally representative survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:336–342. doi: 10.1089/acm.2015.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki R, Eusebius S, Makled M. Is complementary and alternative medicine use associated with cancer screening rates for women with functional disabilities? Complement Ther Med. 2016;24:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ojukwu M, Mbizo J, Leyva B, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among overweight and obese cancer survivors in the United States. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14:503–514. doi: 10.1177/1534735415589347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao JJ, Palmer CS, Healy KE, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer survivors: A population-based study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:8–17. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0153-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Memorial Sloan Kettering, Integrative Medicine Service. [December 14, 2015]; Online document at: www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/treatments/symptom-management/integrative-medicine.

- 13.MD Anderson Integrative Medicine Center. [December 14 2015]; Online document at: www.mdanderson.org/patient-and-cancer-information/care-centers-and-clinics/specialty-and-treatment-centers/integrative-medicine-center/index.html.

- 14.Tasaki K, Maskarinec G, Shumay DM, et al. Communication between physicians and cancer patients about complementary and alternative medicine: Exploring patients’ perspectives. Psychooncology. 2002;11:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pon.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shelley BM, Sussman AL, Williams RL, et al. ‘They don’t ask me so I don’t tell them’: Patient-clinician communication about traditional, complementary, and alternative medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:139–147. doi: 10.1370/afm.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.NCHS. 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS): Public use data release. NHIS survey description. [November 3, 2015];2002 Online document at: http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2002/srvydesc.pdf.

- 17.NCHS. 2007 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS): Public use data release. NHIS survey description. [November 3, 2015];2007 Online document at: http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2007/srvydesc.pdf.

- 18.NCHS. 2012 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS): Public use data release. NHIS survey description. [November 3, 2015];2012 Online document at: http://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2012/srvydesc.pdf.

- 19.Botman SL, Moore TF, Moriarity CL, et al. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 1995–2004. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2000;2:1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons VL, Moriarity CL, Jonas K, et al. Design and estimation for the National Health Interview Survey, 2006–2015. Vital Health Stat. 2014;2:1–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN (Release 11.0.0) [Computer Software] Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment & Survivorship Facts & Figures 2016–2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2016. [August 9, 2017]. Online document at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures/cancer-treatment-and-survivorship-facts-and-figures-2016-2017.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayo Clinic. Alternative cancer treatments: 10 options to consider. [December 14, 2015];2014 Dec 23; Online document at: www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cancer/in-depth/cancer-treatment/art-20047246.

- 24.Deng G, Cassileth BR, Yeung KS. Complementary therapies for cancer-related symptoms. J Support Oncol. 2004;2:419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saxe GA, Madlensky L, Kealey S, et al. Disclosure to physicians of CAM use by breast cancer patients: Findings from the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study. Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7:122–129. doi: 10.1177/1534735408323081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gansler T, Chiewkwei K, Crammer C, et al. A population-based study of prevalence of complementary methods use by cancer survivors. Cancer. 2008;113:1048–1057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. [December 14, 2015];2005 Online document at: www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/34/764/recommendations.pdf.

- 28.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. National Health Statistics Reports 12. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. National health statistics reports; no 79. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oluwadamilola O, White JD. Herbal therapy use by cancer patients: A literature review on case reports. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Advance data from vital and health statistics; no 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henley J, Richards TB, Underwood M, et al. Lung cancer incidence trends among men and women—United States, 2005–2009. MMWR. 2014;63:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ladas EJ, Kelly KM. Integrative Strategies for Cancer Patients: A Practical Research for Managing the Side Effects of Cancer Therapy. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velicer CM, Ulrich CM. Vitamin and mineral supplement use among US adults after cancer diagnosis: A systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:665–673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.5905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hagerty M. Vitamin and Supplement Use in Oncology Patients. [August 9, 2017];Prevention. 2011 May 6; Online document at: www.theoncologynurse.com/ton-issue-archive/issue-archive/3149-ton-3149.

- 36.Baily RL, Fuloni VL, Keast DR, Dwyer JT. Examination of vitamin intakes among US adults by dietary supplement use. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]