Abstract

This survey study analyzes the trends in the distribution of medical education debt by focusing on the increase in graduates without such debt.

Among medical students graduating with educational loans, the mean debt was $32 000 in 1986, which is approximately $70 000 in 2017 dollars.1 Rising tuitions and a growing reliance on loans increased mean medical education debt to $190 000 by 2016.2,3 Alongside these well-known trends is a quieter increase in the proportion of graduates without debt. The combination of these observations suggests a concentration of debt among fewer individuals—a finding that is obscured by population means.1 We sought to analyze the trends in the distribution of medical education debt by focusing on the increase in graduates without such debt.

Methods

We used deidentified data from the 2010-2016 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire (response rates, 78%-83%). We limited analyses to graduates who responded to questions about self-reported medical education debt. We adjusted figures to 2016 dollars4 and stratified medical education debt into the following 4 categories: no debt, $1 to $100 000, $100 001 to $200 000, and greater than $200 000. We performed a sensitivity analysis on the distribution of debt using total educational debt (ie, including debt incurred before medical school). We additionally examined changes in scholarship funds over time. This work was deemed not to be human subjects research.

Results

The number of medical school graduates reporting on debt was 12 786 of 13 904 (92.0%) in 2010 and 13 610 of 15 232 (89.4%) in 2016. Among those with debt, mean amount of debt was $161 739 in 2010 and $179 068 in 2016 (Table). Comparing 2010 and 2016, the proportion of graduates reporting no debt increased from 16.1% (2056 of 12 786) in 2010 to 26.9% (3655 of 13 610) in 2016, while other debt categories remained relatively stable or declined (Figure, A). The exception was those with greater than $300 000 in debt, where the proportion of graduates doubled from 2.1% (263 of 12 786) in 2010 to 4.2% (565 of 13 610) in 2016.

Table. Medical Education Debt by Intended Specialty for US Medical Graduates, 2010-2016 .

| Intended Specialty | 2010 | 2016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graduates, No. | Graduates With Debt, No. (%) | Medical Education Debt, $a,b | Graduates, No. | Graduates With Debt, No. (%) | Medical Education Debt, $a,b | |||

| Mean | Median (IQR) | Mean | Median (IQR) | |||||

| Anesthesiology | 839 | 732 (87.3) | 164 218 | 168 697 (119 242-215 954) |

769 | 576 (74.9) | 181 021 | 182 000 (120 000-250 000) |

| Dermatology | 277 | 213 (76.9) | 145 804 | 142 870 (89 725-197 820) |

330 | 211 (63.9) | 153 827 | 160 000 (85 000-213 000) |

| Emergency medicine | 907 | 811 (89.4) | 174 501 | 181 335 (131 880-219 800) |

1203 | 938 (78.0) | 195 432 | 200 000 (145 000-250 000) |

| Family medicine | 595 | 499 (83.9) | 167 921 | 175 840 (131 880-214 305) |

1170 | 935 (79.9) | 180 729 | 180 000 (130 000-240 000) |

| General surgery | 727 | 601 (82.7) | 162 985 | 170 345 (109 900-216 503) |

832 | 620 (74.5) | 183 285 | 180 000 (130 000-240 000) |

| Internal medicine | 1657 | 1343 (81.1) | 156 857 | 164 850 (104 405-208 810) |

2664 | 1868 (70.1) | 173 278 | 175 000 (115 000-230 000) |

| Medicine and pediatrics | NA | NA | NA | NA | 273 | 216 (79.1) | 169 193 | 173 588 (120 000-220 000) |

| Neurology | 260 | 213 (81.9) | 163 658 | 175 840 (109 900-219 800) |

417 | 289 (69.3) | 180 041 | 180 000 (120 000-250 000) |

| Neurosurgery | 141 | 117 (83.0) | 167 875 | 159 355 (109 900-230 790) |

167 | 110 (65.9) | 180 660 | 187 500 (118 000-260 000) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 746 | 660 (88.5) | 165 934 | 168 147 (113 197-219 800) |

799 | 602 (75.3) | 177 491 | 180 000 (120 000-233 000) |

| Ophthalmology | 327 | 241 (73.7) | 144 322 | 153 860 (87 920-193 424) |

338 | 203 (60.1) | 172 564 | 184 000 (120 000-220 000) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 572 | 494 (86.4) | 165 850 | 175 840 (113 197-219 800) |

612 | 454 (74.2) | 183 778 | 190 000 (130 000-240 000) |

| Otolaryngology | 243 | 195 (80.2) | 158 764 | 164 850 (109 900-202 216) |

244 | 172 (70.5) | 174 801 | 180 000 (110 000-240 000) |

| Pathology | 260 | 206 (79.2) | 148 440 | 150 563 (87 920-192 325) |

184 | 120 (65.2) | 178 146 | 185 539 (117 500-230 000) |

| Pediatrics | 1036 | 887 (85.6) | 156 475 | 164 850 (109 900-203 315) |

1548 | 1151 (74.4) | 174 764 | 177 000 (120 000-225 000) |

| Plastic surgery | 125 | 100 (80.0) | 170 020 | 165 949 (107 153-222 548) |

117 | 87 (74.4) | 180 730 | 175 000 (137 000-240 000) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 149 | 130 (87.2) | 169 111 | 178 588 (109 900-219 800) |

168 | 121 (72.0) | 176 469 | 180 000 (120 000-238 037) |

| Psychiatry | 502 | 419 (83.5) | 158 864 | 164 850 (109 900-208 810) |

658 | 488 (74.2) | 184 323 | 190 000 (126 500-250 000) |

| Radiation oncology | 123 | 96 (78.0) | 147 908 | 139 240 (87 920-197 820) |

126 | 83 (65.9) | 168 297 | 170 000 (100 000-202 000) |

| Radiology | 729 | 604 (82.9) | 159 389 | 164 850 (107 702-219 800) |

552 | 384 (69.6) | 185 490 | 180 500 (130 000-250 000) |

| Urology | 192 | 162 (84.4) | 164 693 | 175 840 (118 692-213 746) |

216 | 156 (72.2) | 171 322 | 176 500 (125 000-220 000) |

| Otherc | 412 | 340 (82.5) | 167 316 | 164 850 (120 890-219 800) |

209 | 151 (72.2) | 181 295 | 183 148 (105 000-250 000) |

| Missingd | 1967 | 1667 (84.7) | 163 046 | 164 850 (109 900-219 800) |

14 | 10 (71.4) | 180 100 | 200 000 (120 000-229 000) |

| Total | 12 786 | 10 730 (83.9) | 161 739 | 164 850 (109 900-218 701) |

13 610 | 9945 (73.1) | 179 068 | 180 000 (120 000-240 000) |

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; NA, not available.

Medical education debt including mean, median, and IQR is that for individuals reporting a nonzero value for debt at the time of graduation.

Dollar amounts are adjusted to 2016 US dollars using the consumer price index for all urban consumers.

Other includes allergy, colorectal surgery, medical genetics, preventive medicine, thoracic surgery, not medicine, undecided, or other unclassified.

Missing includes those who did not respond to the question on intended specialty.

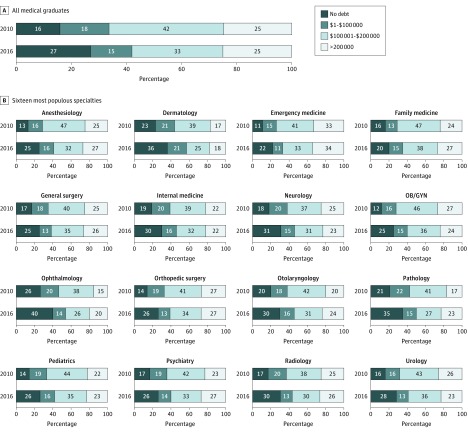

Figure. Distribution of Medical Education Debt by Specialty, 2010 and 2016.

The 16 most populous specialties self-reported by medical graduates in 2016 are displayed. The following specialties were excluded: allergy, colorectal surgery, medical genetics, neurosurgery, physical medicine and rehabilitation, preventive medicine, radiation oncology, thoracic surgery, nonmedical, undecided, other unclassified, or those with missing survey responses to intended specialty. Combined medicine and pediatrics was excluded because data were not available for 2010. OB/GYN indicates obstetrics and gynecology.

By specialty (Figure, B), the cohort with no debt experienced the largest absolute increase between 2010 and 2016. Six specialties experiencing the largest absolute increase in no debt were radiology (17.1% in 2010 and 30.4% in 2016), dermatology (23.1% in 2010 and 36.1% in 2016), neurology (18.1% in 2010 and 30.7% in 2016), obstetrics and gynecology (11.5% in 2010 and 24.7% in 2016), ophthalmology (26.3% in 2010 and 39.9% in 2016), and pathology (20.8% in 2010 and 34.8% in 2016). When examining total educational debt, the mean amount of debt increased to $177 362 in 2010 and $197 426 in 2016, but distribution by specialty remained unchanged.

The mean scholarship funding among recipients did not substantially increase to account for growth in medical graduates without debt, from $53 065 in 2010 to $58 136 in 2016. Among those without debt, the mean amount of scholarship funding declined from $135 186 in 2010 to $52 718 in 2016.

Discussion

Although the real increase in medical student debt is well known, this study offers 3 new observations. First, the proportion of students graduating with no debt is also increasing. Although this finding seems positive, when paired with a decline in scholarship funding within this debt-free cohort, the finding suggests a concentration of medical students with wealthy backgrounds. Second, when paired with an increase in aggregate per capita debt, this finding suggests that medical education debt is concentrated in fewer individuals. Such concentration disguises individual debt burdens behind aggregate debt estimates that, although high, are still lower than what an increasing number of students face. Third, these changing distributions vary considerably by specialty choice. There is no clear association between specialty-specific proportions of graduates without debt and the income typical of those specialties, but primary care–oriented fields seem to have less of an increase in graduates without debt.

The causal associations among debt, specialty choice, and income are challenging to disentangle.5 Conceptually, debt is likely to be less of a determinant of specialty choice than is future income. There is also no consensus on the balance across the medical specialties to best meet the United States’ workforce needs. But to the extent that specialty choice is important and that indebtedness may be associated with it, we need to begin to examine second-order debt effects and, in particular, its distribution across specialties.

References

- 1.Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire (GQ): all schools reports. https://www.aamc.org/data/gq/. Accessed May 1, 2017.

- 2.Greysen SR, Chen C, Mullan F. A history of medical student debt: observations and implications for the future of medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):840-845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Association of American Medical Colleges Medical student education: debt, costs, and loan repayment fact card. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/2016_Debt_Fact_Card.pdf. Published October 2016. Accessed May 4, 2017.

- 4.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Dept of Labor Consumer price index. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/. Accessed May 7, 2017.

- 5.Diehl AK, Kumar V, Gateley A, Appleby JL, O’Keefe ME. Predictors of final specialty choice by internal medicine residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(10):1045-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]