Key Points

Question

Are there systematic differences in the quality of inpatient care provided by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens internal medicine physicians?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort analysis of 1 818 873 Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized between 2009 and 2014, there was no significant difference in 30-day mortality among patients treated by locum tenens physicians compared with those treated by non–locum tenens physicians (8.83% vs 8.70%).

Meaning

Among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries, treatment by locum tenens physicians overall was not associated with excess mortality risk.

Abstract

Importance

Use of locum tenens physicians has increased in the United States, but information about their quality and costs of care is lacking.

Objective

To evaluate quality and costs of care among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized during 2009-2014 was used to compare quality and costs of hospital care delivered by locum tenens and non–locum tenens internal medicine physicians.

Exposures

Treatment by locum tenens general internal medicine physicians.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was 30-day mortality. Secondary outcomes included inpatient Medicare Part B spending, length of stay, and 30-day readmissions. Differences between locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians were estimated using multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for beneficiary clinical and demographic characteristics and hospital fixed effects, which enabled comparisons of clinical outcomes between physicians practicing within the same hospital. In prespecified subgroup analyses, outcomes were reevaluated among hospitals with different levels of intensity of locum tenens physician use.

Results

Of 1 818 873 Medicare admissions treated by general internists, 38 475 (2.1%) received care from a locum tenens physician; 9.3% (4123/44 520) of general internists were temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician at some point. Differences in patient characteristics, demographics, comorbidities, and reason for admission between locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians were not clinically relevant. Treatment by locum tenens physicians, compared with treatment by non–locum tenens physicians (n = 44 520 physicians), was not associated with a significant difference in 30-day mortality (8.83% vs 8.70%; adjusted difference, 0.14%; 95% CI, −0.18% to 0.45%). Patients treated by locum tenens physicians had significantly higher Part B spending ($1836 vs $1712; adjusted difference, $124; 95% CI, $93 to $154), significantly longer mean length of stay (5.64 days vs 5.21 days; adjusted difference, 0.43 days; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.52), and significantly lower 30-day readmissions (22.80% vs 23.83%; adjusted difference, −1.00%; 95% CI −1.57% to −0.54%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries treated by a general internist, there were no significant differences in overall 30-day mortality rates among patients treated by locum tenens compared with non–locum tenens physicians. Additional research may help determine hospital-level factors associated with the quality and costs of care related to locum tenens physicians.

This cohort study evaluates the differences in quality and costs of care related to locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians treating hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries.

Introduction

The use of locum tenens, substitute physicians who cover established clinical positions when full-time physicians are temporarily unavailable, has increased significantly in the United States between 2000 and 2015. Several factors have spurred this demand for locum tenens physicians, including local and regional physician shortages; greater rates of employment by multispecialty group practices and hospitals, which have higher physician turnover than smaller practices; and increasing demand for clinical services among newly insured patients.

At the same time, single, small group, and rural physician practices depend on locum tenens physicians for coverage during vacations and conferences. Demand for locum tenens physicians has been highest in primary care, psychiatry, and hospitalist medicine. Outside of the United States, hospitals and practices in several countries, including the United Kingdom and Australia, also rely heavily on locum tenens physicians.

Despite the importance of locum tenens physicians in US health care, comprehensive national data on the quality and costs of care of these physicians are lacking. Because locum tenens physicians typically spend limited amounts of time at any single institution, their relative unfamiliarity with a hospital’s systems (including electronic health records), staff, hospital culture, and local postacute care options could, among other reasons, predispose to worse patient outcomes and increased costs of inpatient care. Therefore, national data on Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized at acute care hospitals during 2009-2014 and treated by a general internist were used to evaluate the quality and costs of care provided by locum tenens physicians.

Methods

This study was approved by the Harvard Medical School institutional review board, which waived participant consent.

Study Sample and Data Sources

This study included all acute care hospitalizations identified in a random sample of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries aged 65 years and older during 2009-2014. For 2011-2014, these acute care hospitalizations were identified using the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review 20% files linked by beneficiary identification to the 20% Medicare Carrier files. For 2009-2010, 5% random Medicare claims samples were used because 20% Medicare files were not available. Hospital characteristics were obtained from the 2011 American Hospital Association Annual Survey.

Identification of Locum Tenens Hospitalizations

The study sample included hospitalizations in which the assigned attending physician was a general internal medicine physician. Physicians were assigned to each hospitalization based on the physician’s National Provider Identifier (NPI) in the Carrier File that accounted for the plurality of inpatient evaluation and management services during that hospitalization. The study sample was restricted to hospitalizations in which the assigned physician had a designated specialty of “internal medicine,” identified by NPI through a comprehensive physician database with specialty information obtained from multiple sources, including the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System Registry, the American Board of Medical Specialties, and state licensing boards.

Locum tenens hospitalizations were defined as those in which a locum tenens physician provided the plurality of evaluation and management visits. Locum tenens physicians’ evaluation and management claims were ascertained using the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System modifier code Q6, which identifies services furnished by locum tenens physicians and is applied in the Carrier File to the NPI of the regular physician for whom the locum tenens physician is covering. Although the term locum tenens is often used broadly to refer to any temporary physician hire, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations specifically designate that the locum tenens modifier code only be used when (1) the locum tenens physician is covering an established clinical position that has been temporarily or permanently vacated, (2) the locum tenens physician provides 60 days or more of coverage, and (3) the locum tenens physician is not a member of the practice that is seeking coverage. Therefore, according to the definition by CMS, locum tenens physicians provide temporary coverage for non–locum tenens physicians with established clinical positions. Physicians hired temporarily to fill new clinical positions (eg, to increase staffing during periods of excess seasonal demand or to temporarily fill a new clinical position) are not locum tenens.

Of note, the number of locum tenens physicians could not be identified because Medicare data do not include the NPI of the locum tenens physician, but rather the NPI of the physician who was temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician. Because a single locum tenens physician may temporarily cover the care of multiple non–locum tenens physicians, the data can therefore only provide information on how many physicians are temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician, rather than the number of locum tenens physicians providing care.

Study Outcomes and Covariates

We compared quality and costs of care during hospitalizations involving locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality (death within 30 days of admission); secondary outcomes included inpatient costs of care, 30-day readmission rates, and length of stay. Costs were defined as total Medicare Part B spending per hospitalization because Part B spending encompasses professional and other services at a physician’s discretion and is therefore a proxy for inpatient resource use.

Covariates included patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid eligibility status (“dual eligibility”), and patient-level Elixhauser comorbidity indicators for 31 conditions. Race and ethnicity were defined using standard fixed categories available in Medicare claims and originally provided to Medicare by the US Social Security Administration; these data were included because they are associated with care quality and spending, and therefore, they are important potential confounders. The reported diagnosis-related group (DRG) was used to assign each admission into 1 of 25 mutually exclusive major diagnostic categories. Indicator variables for admission month were included to control for seasonal differences in locum tenens physician use that could correlate with outcomes. In addition, indicator variables for day of week of admission were added to control for factors associated with day of admission—such as staffing patterns and patient severity of illness—that might also correlate with outcomes. Furthermore, hospital fixed effects (ie, hospital-specific indicator variables) were included to account for hospital characteristics—including unmeasured differences in patient populations and systematic differences in care quality—that remain stable over time.

Statistical Analysis

Characteristics of patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians were compared. Tests for observable differences in patient demographics and illness severity, including preexisting chronic conditions and the full distribution of admission diagnoses (DRGs) were performed. The geographic distribution and structural characteristics of hospitals where locum tenens physicians practice, including variations in locum tenens physician use across the 306 US hospital referral regions, which are regional markets for tertiary care, were also described.

A hospitalization-level multivariable logistic regression was estimated, modeling 30-day mortality as a function of whether care was provided by a locum tenens physician (indicator variable), patient covariates, indicator variables for day of the week and month of admission, and hospital fixed effects. Identical multivariable linear regressions were estimated for Medicare Part B spending and length of stay. Hospital fixed effects accounted for the possibility that locum tenens physicians may disproportionately practice in hospitals with systematically different quality of care, and indicator variables for month of admission controlled for seasonal differences, which could confound the analyses. This approach therefore compared differences in outcomes between locum tenens and non–locum tenens hospitalizations within the same hospital and month.

All models included robust variance estimators to account for clustering of admissions within hospitals. Adjusted patient outcomes for locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians were calculated using the marginal standardization form of predictive margins. We also assessed whether patient mortality was associated with locum tenens care in prespecified subgroups defined by hospital size, hospital profit status, and “locum intensity.” Locum intensity was defined as the percentage of hospitalizations involving a locum tenens physician among hospitals with any locum use. This measure was designed to assess whether a hospital’s degree of experience with locum tenens physicians modified the association between treatment by a locum tenens physician and mortality. In each subgroup analysis, a formal test of interaction was conducted on the basis of standard errors of the regression coefficient on the interaction term between the locum tenens indicator variable and indicator variables for a given subgroup.

Additional Analyses

An analysis was performed to assess for unobservable, systematic differences in case mix between locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians. Some primary care physicians care for their primary care patients when they are hospitalized. If primary care physicians with sicker outpatient panels are more likely to use locum tenens physician coverage, then hospitalized patients cared for by covering locum tenens physicians could have a higher unobserved 30-day mortality risk. To account for this potential confounder, the mortality regression model was re-estimated using the NPI of the physician covered by the locum tenens physician to control for physician-level, rather than hospital-level, fixed effects. In this way, time-invariant characteristics of physicians covered by locum tenens physicians, including differences in outpatient case mix, were accounted for.

A trend analysis was also performed to evaluate for changes in the relationship between locum tenens physician care and patient 30-day mortality between 2009 and 2014. This analysis was performed for all patients in the study cohort and among patients treated at hospitals with high, medium, and low intensity of locum tenens physician use. For each group, the locum tenens indicator variable was interacted with year indicators, which allowed for the association between locum tenens care and a given outcome to vary nonmonotonically by year. All analyses were performed in R (version 3.2; R Foundation) and Stata (version 14; StataCorp). The 95% CIs around reported estimates reflect 0.025 in each tail or P ≤ .05.

Results

The study sample included 1 708 398 non–locum tenens hospitalizations and 38 475 locum tenens hospitalizations (2.1% of hospitalizations) at 1590 hospitals. Approximately 9.3% of non–locum tenens general internists in the study sample (4123/44 520) were temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician at some point.

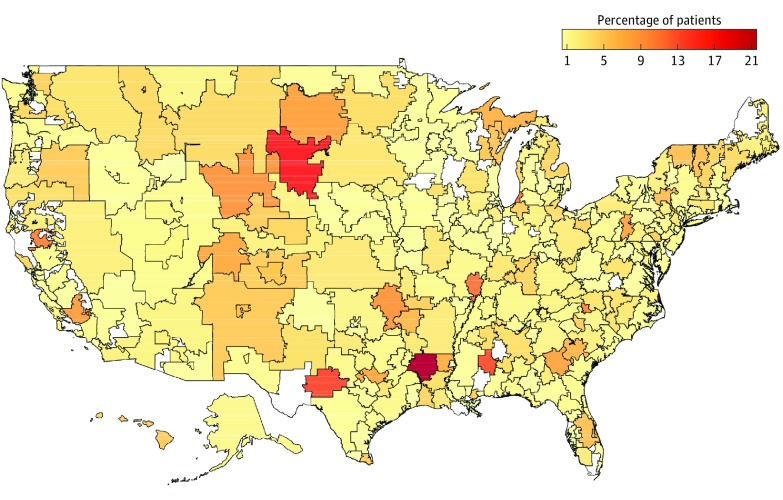

Intensity of locum tenens physician use varied substantially across hospital referral regions, ranging from close to zero percent of Medicare inpatient admissions in some hospital referral regions to more than 15% of admissions in others (Figure 1). Compared with non–locum tenens physicians, locum tenens physicians disproportionately practiced in the South and West census regions, in smaller suburban and rural hospitals (vs urban), and in public hospitals (Table 1).

Figure 1. Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens Physicians in 2009-2014, by Hospital Referral Region.

White areas correspond to regions that are not part of a hospital referral region.

Table 1. Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians During 2009-2014.

| Characteristic | Hospitalized Patients Treated by Non–Locum Tenens Physiciansa (No. of Hospitalizations = 1 780 398) |

Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens Physiciansb (No. of Hospitalizations = 38 475) |

P Valuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 74.8 (13.2) | 74.3 (13.1) | <.001 |

| Female, % | 59.2 | 58.7 | .05 |

| White, % | 83.4 | 85.3 | <.001 |

| Dual eligibility, %d | 26.9 | 29.5 | <.001 |

| Elixhauser Index score, mean (SD)e | 5.7 (3.2) | 5.6 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Elixhauser conditions, %f | |||

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 63.4 | 64.5 | <.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 44.1 | 43.5 | .009 |

| Congestive heart failure | 36.2 | 35.7 | .05 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 30.8 | 29.2 | <.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 16.3 | 15.0 | <.001 |

| Valvular disease | 16.1 | 14.5 | <.001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 13.5 | 13.4 | .63 |

| Endocrine disease | |||

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 34.7 | 35.3 | .02 |

| Hypothyroidism | 23.8 | 24.1 | .23 |

| Obesity | 16.7 | 16.7 | .77 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 13.0 | 12.3 | <.001 |

| Cancer | |||

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 9.2 | 8.8 | .005 |

| Metastatic cancer | 4.7 | 4.3 | .001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 42.9 | 43.7 | .002 |

| Renal failure | 31.4 | 30.3 | <.001 |

| Depression | 24.7 | 24.2 | .02 |

| Other neurological disorders | 20.9 | 20.2 | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular | 6.3 | 6.1 | .07 |

| Liver disease | 6.1 | 5.8 | .02 |

| Proportion of patients admitted on a weekend, %g | 22.3 | 24.0 | <.001 |

| Hospital census region, No. (%)h | |||

| Northeast [n = 250] | 315 524 (17.7) | 5232 (13.6) | <.001 |

| Midwest [n = 354] | 375 924 (21.1) | 6742 (17.5) | |

| South [n = 672] | 806 022 (45.3) | 19 765 (51.4) | |

| West [n = 314] | 282 928 (15.9) | 6736 (17.5) | |

| Hospital size, No. (%)h | |||

| Small (<100 beds) [n = 489] | 138 741 (7.8) | 6807 (17.7) | <.001 |

| Medium (100-399 beds) [n = 834] | 956 670 (53.7) | 24 574 (63.9) | |

| Large (≥400 beds) [n = 267] | 684 987 (38.5) | 7094 (18.4) | |

| Hospital type, No. (%)h | |||

| Public [n = 248] | 200 334 (11.3) | 5204 (13.5) | <.001 |

| For-profit [n = 293] | 272 669 (15.3) | 6442 (16.7) | |

| Nonprofit [n = 1049] | 1 307 395 (73.4) | 26 829 (69.7) | |

| Hospital geography, No. (%)h | |||

| Urban [n = 986] | 1 515 728 (85.1) | 25 967 (67.5) | <.001 |

| Suburban [n = 343] | 203 593 (11.4) | 9679 (25.2) | |

| Rural [n = 255] | 54 956 (3.1) | 2764 (7.2) | |

| Locum tenens intensity terciles, No. (%)i | |||

| Lowest | 891 651 (50.1) | 1397 (3.6) | <.001 |

| Middle | 541 704 (30.4) | 6537 (17.0) | |

| Highest | 347 043 (19.5) | 30 541 (79.4) |

Locum tenens physicians provided temporary coverage for 4123 non–locum tenens physicians during the study period.

Includes patients treated by 44 520 non–locum tenens physicians.

P values estimated using 2-sample t tests or z tests for proportions, as appropriate.

Dual eligibility refers to patients who are eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

The Elixhauser Index ranges from 0 to 31 and each comorbidity equals 1 index point. Higher Elixhauser Indices indicate the presence of greater numbers of comorbidities and are associated with longer lengths of stay, higher hospital charges for care, and higher patient mortality.

Elixhauser comorbidities were chosen based on their prevalence and their likelihood of being associated with common indications for inpatient treatment by general internal medicine physicians. The following Elixhauser conditions were excluded from the table for simplicity: paralysis, peptic ulcer disease, AIDS/HIV, lymphoma, coagulopathy, weight loss, fluid and electrolyte disorders, blood loss anemia, deficiency anemia, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and psychoses.

Proportion of all Medicare beneficiaries treated by locum tenens physicians or non–locum tenens physicians who were admitted on a Saturday or Sunday.

Numbers in brackets represent the number of different hospitals in each subcategory.

Among hospitals with any locum tenens use, we computed the percentage of a hospital’s patients treated by a locum tenens physician, and divided hospitals into terciles along that metric. The lower tercile hospitals involved locum tenens physicians in 0.01% to less than 0.45% of their admissions, the middle tercile in 0.45% to less than 2.5% of admissions, and the upper tercile in at least 2.5% of all admissions.

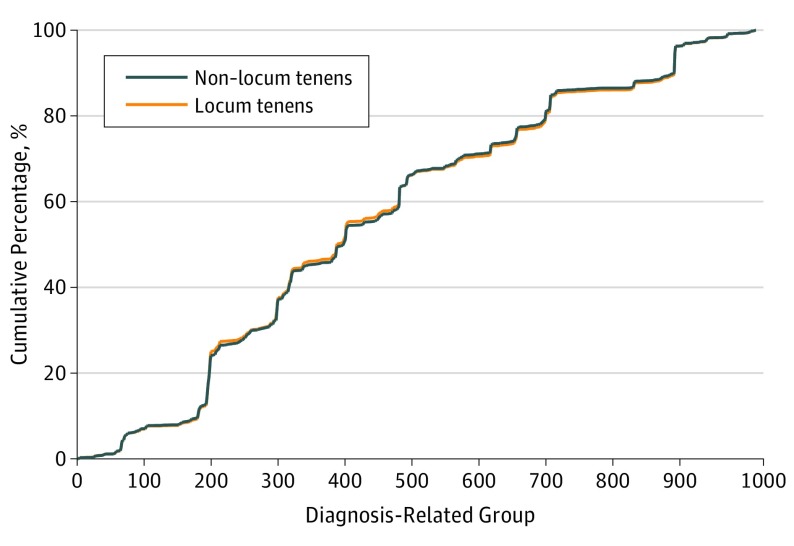

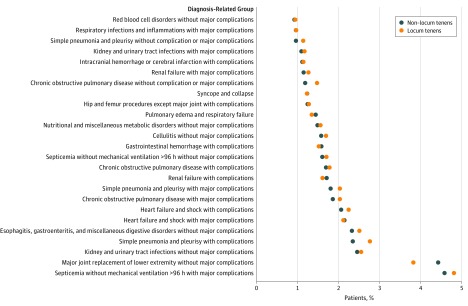

No clinically relevant differences were observed in the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians and statistically significant differences (including age and several chronic conditions) were small in magnitude (Table 1). After adjusting comparisons of patient characteristics for hospital fixed effects (ie, assessing the balance of patient characteristics within hospital), fewer significant differences between patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians were observed (eTable 1 in Supplement). There were no significant differences in the distributions of DRG diagnoses and modal admission DRG diagnoses between patients cared for by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2. Cumulative Distributions of Admitting Diagnosis-Related Groups in 2009-2014.

Cumulative distributions of the admitting diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) for all hospitalized patients in the study sample, grouped by locum tenens (orange line) vs non–locum tenens (blue line) physicians. Although DRG numbers are categorical values representing separate diagnoses, we graphed the cumulative distribution on a continuous scale to visualize the composition of admissions diagnoses of hospitalized patients across hundreds of DRGs. Therefore, the overlap between the 2 distributions can reveal subtle differences in admissions diagnosis mix across these many diagnoses.

Figure 3. Diagnosis-Related Group Diagnoses for Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians in 2009-2014.

Percentage of hospitalized patients treated by locum tenens (orange circles) and non–locum tenens (blue circles) physicians with each of the 25 most common admitting diagnosis-related groups. Percentages were calculated by determining the volume of patients with a given admitting diagnosis-related group who were treated by locum tenens (non–locum tenens) physicians and dividing this value by the total number of hospitalized patients treated by locum tenens (non–locum tenens) physicians: equal to 38 475 hospitalized patients for locum tenens physicians and 1 780 398 for non–locum tenens physicians.

Patient Outcomes

Unadjusted 30-day mortality was 9.01% (95% CI, 8.73%-9.30%; 3501/38 475) for patients treated by locum tenens physicians vs 8.69% (95% CI, 8.64%-8.73%; 154 717 /1 780 398) for patients treated by non–locum tenens physicians). There was no significant difference in adjusted 30-day mortality between patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians (8.83% [95% CI, 8.52%-9.14%] vs 8.70% [95% CI, 8.69%-8.70%]; absolute adjusted difference, 0.14% [95% CI −0.18% to 0.45%]) (Table 2).

Table 2. Outcomes and Costs of Care of Hospitalizations Treated by Locum Tenens and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians During 2009-2014a.

| Outcome | Hospitalized Patients Treated by Non–Locum Tenens Physiciansb (No. of Hospitalizations = 1 780 398) |

Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens Physiciansc (No. of Hospitalizations = 38 475) |

Difference (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Analysis | ||||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 30-d Mortality, % (95% CI) | 8.69 (8.64 to 8.73) | 9.01 (8.73 to 9.30) | 0.33 (−0.14 to 0.80) | 1.04 (0.98 to 1.10) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| 30-d Readmissions, % (95% CI) | 23.83 (23.77 to 23.90) | 22.42 (21.98 to 22.86) | −1.42 (−2.38 to −0.45) | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.98) |

| Mean total part B charges, $ (95% CI) | 1716 (1713 to 1719) | 1668 (1650 to 1685) | −48 (−136 to 40) | NA |

| Mean length of stay, d (95% CI) | 5.22 (5.21 to 5.22) | 5.36 (5.31 to 5.41) | 0.14 (−0.03 to 0.31) | NA |

| Adjusted Analysis | ||||

| Primary outcome | ||||

| 30-d Mortality, % (95% CI) | 8.70 (8.69 to 8.70) | 8.83 (8.52 to 9.14) | 0.14 (−0.18 to 0.45) | 1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| 30-d Readmissions, % (95% CI) | 23.83 (23.82 to 23.84) | 22.80 (22.26 to 23.28) | −1.00 (−1.57 to −0.54) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.96) |

| Mean total part B charges, $ (95% CI) | 1712 (1712 to 1713) | 1836 (1806 to 1866) | 124 (93 to 154) | NA |

| Mean length of stay, d (95% CI) | 5.21 (5.21 to 5.21) | 5.64 (5.55 to 5.73) | 0.43 (0.34 to 0.52) | NA |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Estimates were adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, month of year of admission, day of week of admission, Medicaid eligibility, Elixhauser indicators for 31 conditions, the admitting Major Diagnostic Category, and hospital fixed effects, with robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level.

Locum tenens physicians provided temporary coverage for 4123 non–locum tenens physicians during the study period.

Includes patients treated by 44 520 non–locum tenens physicians.

Patients treated by locum tenens physicians had significantly higher adjusted total Part B charges ($1836 [95% CI, $1806-$1866] vs $1712 [95% CI, $1712-$1713]; absolute adjusted difference, $124 [95% CI, $93-$154]), longer lengths of stay (adjusted mean length of stay, 5.64 days [95% CI, 5.55-5.73] vs 5.21 days [95% CI, 5.21-5.21]; adjusted difference, 0.43 days [95% CI, 0.34-0.52]), and significantly lower readmission rates (22.80% [95% CI, 22.26%-23.28%] vs 23.83% [95% CI, 23.82%-23.84%]; adjusted difference, −1.00% [95% CI, −1.57% to −0.54%]) than patients treated by non–locum tenens physicians (Table 2).

Subgroup Analysis

In prespecified subgroup analyses over the full study period (2009-2014), adjusted 30-day mortality was significantly higher among patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians at hospitals in the lowest tercile of locum tenens intensity (11.63% [95% CI, 9.96%-13.30%] vs 8.53% [95% CI, 8.53%-8.53%]; absolute difference, 3.10% [95% CI, 1.43%-4.77%]; adjusted odds ratio, 1.47 [95% CI, 1.22-1.77]; both P values <.001 for interactions of locum tenens physicians with indicator variables for hospitals in the middle and upper terciles of locum tenens intensity, respectively, relative to hospitals in the lowest tercile of locum tenens intensity) (Table 3). However, in year-by-year analysis of patients admitted to hospitals in the lowest tercile of locum tenens intensity, mortality differences between patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians were largest during 2009-2012 (statistically significantly different from zero in 2011-2012 but not significant in 2009-2010) and nonsignificant and close to zero in magnitude during 2013-2014. Differences in annual 30-day mortality rates among all patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians, and among subgroups of patients treated at low, medium, and high locum tenens intensity hospitals, did not vary by year in a trend analysis (Table 4; eTable 2 in the Supplement). No effect modification was observed according to hospital size or for-profit status (Table 3).

Table 3. Adjusted 30-Day Mortality of Hospitalizations Treated by Locum Tenens and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians During 2009-2014, Stratified by Hospital Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Hospitalized Patients Treated by Non–Locum Tenens Physiciansa | Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum Tenens Physiciansb | Difference, % (95% CI) |

Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

P Valuec | P Value for Interactiond | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Hospitalizations | Adjusted 30-d Mortality (95% CI) |

No. of Hospitalizations | Adjusted 30-d Mortality (95% CI) |

|||||

| Overall | 1 780 398 | 8.70 (8.69 to 8.70) |

38 475 | 8.83 (8.52 to 9.14) |

0.14 (−0.18 to 0.45) |

1.02 (0.98 to 1.06) |

.40 | NA |

| Hospital sizee | ||||||||

| Small | 138 741 | 9.12 (9.08 to 9.15) |

6807 | 9.42 (8.67 to 10.18) |

0.31 (−0.49 to 1.10) |

1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) |

.45 | [Reference] |

| Medium | 956 670 | 8.91 (8.90 to 8.91) |

24 574 | 8.92 (8.55 to 9.30) |

0.02 (−0.37 to 0.41) |

1.00 (0.95 to 1.06) |

.92 | .55 |

| Large | 684 987 | 8.31 (8.31 to 8.32) |

7094 | 8.76 (7.99 to 9.54) |

0.45 (−0.34 to 1.23) |

1.07 (0.96 to 1.19) |

.26 | .73 |

| Hospital type | ||||||||

| Public | 200 334 | 9.25 (9.23 to 9.27) |

5204 | 8.72 (7.96 to 9.48) |

−0.53 (−1.31 to 0.25) |

0.93 (0.84 to 1.04) |

.18 | [Reference] |

| For-profit | 272 669 | 8.43 (8.41 to 8.45) |

6442 | 8.52 (7.74 to 9.30) |

0.09 (−0.71 to 0.89) |

1.01 (0.90 to 1.14) |

.83 | .30 |

| Non-profit | 1 307 395 | 8.67 (8.66 to 8.68) |

26 829 | 8.94 (8.57 to 9.32) |

0.28 (−0.11 to 0.66) |

1.04 (0.99 to 1.09) |

.16 | .08 |

| Locum intensity, by tercilef | ||||||||

| Lower | 891 651 | 8.53 (8.53 to 8.53) |

1397 | 11.63 (9.96 to 13.30) |

3.10 (1.43 to 4.77) |

1.47 (1.22 to 1.77) |

<.001 | [Reference] |

| Middle | 541 704 | 8.84 (8.83 to 8.85) |

6537 | 8.72 (8.05 to 9.39) |

−0.12 (−0.80 to 0.55) |

0.98 (0.89 to 1.08) |

.72 | <.001 |

| Upper | 347 043 | 8.89 (8.86 to 8.92) |

30 541 | 8.95 (8.60 to 9.29) |

0.06 (−0.32 to 0.43) |

1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) |

.76 | <.001 |

Locum tenens physicians provided temporary coverage for 4123 non–locum tenens physicians during the study period.

Includes patients treated by 44 520 non–locum tenens physicians.

P value is for comparison of 30-day mortality among hospitalized patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians in each subgroup.

P value for interaction assesses how the difference in 30-day mortality between hospitalized patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians is modified by each category subgroup and was obtained from a formal test of interaction.

Small hospitals are defined as those with fewer than 100 beds; medium hospitals as those with between 100 and 399 beds; and large hospitals as those with 400 or more beds, according to the annual American Hospital Association survey.

Among hospitals with any locum tenens use, we computed the percentage of a hospital’s patients treated by a locum tenens physician, and divided hospitals into terciles along that metric. The lower tercile hospitals involved locum tenens physicians in 0.01% to less than 0.45% of their admissions, the middle tercile in 0.45% to less than 2.5% of admissions, and the upper tercile in at least 2.5% of all admissions. All estimates were adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, month of year of admission, day of week of admission, Medicaid eligibility, indicators for 31 Elixhauser conditions, and the admitting Major Diagnostic Category, and hospital fixed effects, with robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level.

Table 4. Annual Adjusted Difference in 30-Day Mortality Among Patients Treated by Locum Tenens and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians, Overall and Stratified by Tercile of Intensity of Locum Tenens Physician Usea.

| Locum Tenens Intensity, by Tercileb | Mortality Difference, % (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | |

| Overall | 0.6 (−0.5 to 1.7) | 0.8 (−0.2 to 1.8) | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.3) | 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.1) | −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.4) | 0.1 (−0.6 to 0.8) |

| Lower | 3.6 (−0.1 to 7.4) | 2.7 (−2.0 to 7.3) | 5.1 (1.2 to 8.9) | 7.0 (2.6 to 11.3) | −1.4 (−4.5 to 1.7) | 1.8 (−1.9 to 5.4) |

| Middle | −0.1 (−2.0 to 2.3) | −0.4 (−2.6 to 1.8) | 0.2 (−1.2 to 1.5) | 0.0 (−1.7 to 1.6) | −0.3 (−1.8 to 1.1) | −0.2 (−1.6 to 1.2) |

| Upper | 0.1 (−1.1 to 1.5) | 0.9 (−0.2 to 2.0) | −0.7 (−1.4 to 0.04) | 0.3 (−0.5 to 1.1) | 0.2 (−1.0 to 0.7) | 0.7 (−0.2 to 1.5) |

Table presents the annual adjusted difference in mortality between patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians in a given year. Positive adjusted differences indicate higher adjusted 30-day mortality among patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians. All estimates were adjusted for patient age, sex, race/ethnicity, month of year of admission, day of week of admission, Medicaid eligibility, indicators for 31 Elixhauser conditions, and the admitting Major Diagnostic Category, and hospital fixed effects, with robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level. Trend tests were performed to assess for trends in adjusted differences in mortality among all patients and among each locum intensity tercile subgroup. These tests were nonsignificant (using P < .10 as cutoff for statistical significance).

Among hospitals with any locum tenens physician use, we computed the percentage of a hospital’s patients treated by a locum tenens physician, and divided hospitals into terciles along that metric. The lower tercile hospitals involved locum tenens physicians in 0.01% to less than 0.45% of their admissions, the middle tercile in 0.45% to less than 2.5% of admissions, and the upper tercile in at least 2.5% of all admissions.

Additional Analyses

In analyses adjusted for physician fixed effects, patients hospitalized during periods of locums tenens physician coverage were not systematically unhealthier than patients hospitalized during other periods, and care by locums tenens physicians was not associated with a difference in 30-day mortality (eTable 3 and eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized at acute care hospitals and treated by a general internist, no significant differences in 30-day mortality rates were observed among patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians. Overall, patients treated by locum tenens physicians had slightly higher Medicare Part B charges, longer lengths of stay, and lower 30-day readmission rates compared with patients within the same hospital who were treated by non–locum tenens physicians. Most patients treated by locum tenens physicians received care at small- and medium-sized hospitals in rural and suburban regions. To our knowledge, this is the first study using national data to characterize locum tenens physicians’ patterns, quality, and costs of care.

A locum tenens physician is formally defined as a physician who provides temporary coverage for another physician from a different practice or institution. In the United States, the term locum tenens is often used to refer to all temporary physicians (eg, physicians hired temporarily when clinical volumes increase). The definition of a locum tenens by CMS is consistent with the term’s formal definition. Accordingly, CMS restricts billing under the locum Q6 modifier to care episodes that meet this definition. Thus, while Q6 is likely to be highly specific for identifying traditional locum tenens physicians, it will not capture other forms of services delivered by temporary physicians who do not meet the locum tenens definition of CMS.

While the CMS definition of locum tenens may not be perfectly sensitive for all temporary physician services, these findings may still have implications for care quality and spending given the number of patients treated by locum tenens physicians. In this study, 2.1% of Medicare inpatients treated by general internists received care from a locum tenens physician, as defined by CMS. Moreover, 9.3% of physicians were temporarily covered by a locum tenens physician during the study period. Furthermore, it is unclear why temporary physicians who do not meet the traditional locum tenens definition would have different mortality, readmissions, or spending patterns than traditional locum tenens physicians.

The lack of a significant overall difference in mortality rates between patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians is reassuring, and it argues against the presence of systematic differences in the quality of care administered by these 2 groups of physicians. The analysis of year-by-year mortality among patients treated by locum tenens vs non–locum tenens physicians did not reveal any statistically significant differences in mortality rates between these 2 patient populations. However, in 2009-2010, mortality rates among patients treated by locum tenens physicians were nonsignificantly higher than those treated by non–locum tenens physicians. Given the study’s modest sample size, a small statistically significant difference in mortality during these earlier years cannot be ruled out. Even so, the lack of suggestion of a mortality difference during 2011-2014 indicates that any small differences in care quality between patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians, and any systematic problems in the use of locum tenens physicians that could have predisposed to this difference in outcomes, in the early period of this study (2009-2010) has resolved. It is also possible that the small nonsignificant mortality differences observed in 2009-2010 reflect confounding due to unmeasured variables associated with the use of locum tenens physicians.

In subgroup analyses, treatment by a locum tenens physician was associated with significantly higher mortality among patients admitted to hospitals that used locum tenens physicians infrequently. It is plausible that hospitals that use locum tenens physicians infrequently may lack adequate support systems to help locum tenens physicians transition into temporary clinical positions and minimize any associated quality lapses, or hire less-skilled locum tenens physicians. However, this subgroup result should be considered to be hypothesis-generating given the retrospective nature of this study’s design, the lack of a difference in the primary mortality outcome in the overall sample, the small sample sizes in the low-intensity tercile subgroup, and the lack of evidence of a difference in mortality in the low-intensity tercile in the most recent years 2013-2014.

Several factors may predispose to higher spending and longer length of stay among patients treated by locum tenens physicians. Physicians may have little prior work experience at the institutions that hire them for locum tenens positions. A physician’s clinical performance may be affected not only by individual skill, overall experience, and organizational performance, but also by institution-specific experience. Several facets of clinical care, including care protocols, resource availability, and clinical norms, vary substantially across health systems. Therefore, temporary physicians, including locum tenens physicians, may initially struggle to efficiently and effectively deliver care or coordinate care transitions. In a survey of 259 managers of health care facilities that use locum tenens physicians, among the most commonly cited drawbacks to hiring temporary physician staff were lack of familiarity with the department or practice (49%) and locum tenens physicians’ need to learn to use new equipment (32%). The longer lengths of stay and higher Medicare Part B charges observed in this study among patients treated by locum tenens physicians are potentially consistent with this explanation. In addition, many hospitals deliver inpatient care in multidisciplinary teams. While high-functioning teams can improve clinical outcomes and reduce spending, they take time to develop, and team members’ familiarity with one another is an important determinant of team performance.

Concerns have been raised abroad that locum tenens physicians may have different clinical competencies than the physicians whom they replace. In the United Kingdom in the early 1990s, concerns about locum tenens physicians’ clinical competency resulted in the creation of a Working Group on Locum Physicians and the development of competency standards and evaluation guidelines for locum tenens physicians. In the United States, many locum tenens positions are filled through national physician staffing agencies, which vet candidates before placing them. Although this study found no evidence of a statistically significant overall difference in mortality rates of patients treated by locum tenens physicians, the United States lacks overarching competency and quality standards for these physicians. Furthermore, because locum tenens physicians bill for clinical services under the NPI of the physician whom they replace, no mechanism currently exists for using administrative data to serially evaluate individual locum tenens physicians’ quality and costs of care.

This study also found that receiving treatment from a locum tenens physician was associated with lower 30-day readmission rates. The discordance between this finding and the lack of association between treatment by a locum tenens physician and 30-day mortality is consistent with previous work demonstrating that, across hospitals, differences in 30-day readmission rates do not correlate well with differences in 30-day mortality. Moreover, the only previous study to evaluate physician-level 30-day mortality rates and 30-day readmissions rates found no relationship between these 2 outcomes at the physician level. Furthermore, this study’s findings also suggest that, if locum tenens physicians deliver more expensive inpatient care than non–locum tenens physicians, this higher spending may be offset by lower spending on 30-day readmissions.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the results should be interpreted cautiously given the limitations inherent in retrospective study designs. Prospective comparisons of outcomes among patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians are necessary to corroborate this study’s findings. Moreover, additional work is needed to understand the characteristics of locum tenens physicians; hospital-specific and experiential determinants of the quality of care that they deliver; and the quality and costs of outpatient, pediatric, and surgical services delivered by locum tenens physicians. CMS and private insurers could facilitate evaluations of physician-level variations in quality and spending by requiring that locum tenens physicians submit identifying information with the billing claim. Second, it is possible that unmeasured patient confounders that correlate with locum tenens care were not accounted for. Efforts to account for unmeasured confounding included analyzing outcomes of locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians within the same hospital, demonstrating similarities of patient characteristics between the 2 groups of physicians, and conducting sensitivity analyses. Third, no information on locum tenens physicians’ characteristics, including age, training, and board certification, was available. Fourth, information was lacking on how hospitals attempt to orient locum tenens physicians to, and support, their clinical positions, which may influence care quality. Fifth, this study evaluated inpatient care delivered by general internists. The study’s findings may not generalize to other specialties or clinical settings. Sixth, this study did not evaluate care delivered by non–locums tenens temporary physician staff. Nonetheless, factors that could account for differences in outcomes between patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians—including challenges delivering care effectively in new health systems—may also deleteriously affect care quality among other temporary physicians. If non–locums tenens temporary physicians have similar outcomes to locum tenens physicians evaluated in this study, reclassifying them as locum tenens physicians could result in a statistically significant overall difference in mortality between locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians. However, the small nonsignificant difference in mortality between patients treated by locum tenens and non–locum tenens physicians observed in this study, and the narrow confidence intervals around this estimate, suggest that if a true difference in mortality exists, it is likely to be very small in absolute terms. Seventh, because Medicare data do not include specific identifiers for locum tenens physicians, our study could not determine the number of physicians who provide locum tenens care to Medicare beneficiaries.

Conclusions

Among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries treated by a general internist, there were no significant differences in overall 30-day mortality rates among patients treated by locum tenens compared with non–locum tenens physicians. Additional research may help determine hospital-level factors associated with the quality and costs of care related to locum tenens physicians.

eTable 1. Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients After Adjustment for Hospital Fixed Effects.

eTable 2. Yearly Unadjusted and Adjusted 30-Day Mortality Among Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians, Overall and by Tercile of Locum Tenens Intensity.

eTable 3. Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients After Adjustment for Physician Fixed Effects.

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses Evaluating Adjustment for Physician Fixed Effects and Use of a Linear Probability Model.

References

- 1.Staff Care 2015 Survey of Temporary Physician Staffing Trends Based on 2014 Data. https://www.staffcare.com/uploadedFiles/2015-survey-temporary-physician-staffing-trends.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 2.Zimlich R. The rise of locum tenens among primary care physicians. Med Econ. 2014;91(7):58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon AB, Alonzo AA. The demography, career pattern, and motivation of locum tenens physicians in the United States. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49(6):363-375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staff Care Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants: Supply, Distribution, and Scope of Practice Considerations. https://www.staffcare.com/nurse-practitioners-physician-assistants-supply-distribution-and-scope-white-paper/. Published 2015. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 5.Poole SR, Efird D, Wera T, Fox-Gliessman D, Hill K. Pediatric locum tenens provided by an academic center. Pediatrics. 1996;98(3, pt 1):403-409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doty B, Andres M, Zuckerman R, Borgstrom D. Use of locum tenens surgeons to provide surgical care in small rural hospitals. World J Surg. 2009;33(2):228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sim AJ. Locum tenens consultant doctors in a rural general hospital: an essential part of the medical workforce or an expensive stopgap? Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(4):1594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Speroff T, Nwosu S, Greevy R, et al. . Organisational culture: variation across hospitals and connection to patient safety climate. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):592-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu R, Carty MJ, Orgill DP, Lipsitz SR, Duclos A. The teaming curve: a longitudinal study of the influence of surgical team familiarity on operative time. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):953-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell EG, Singer S, Kitch BT, Iezzoni LI, Meyer GS. Patient safety climate in hospitals: act locally on variation across units. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(7):319-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Health Forum AHA Annual Survey Database. https://www.ahadataviewer.com/additional-data-products/AHA-Survey/. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 12.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):206-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in academic rank in us medical schools in 2014. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1149-1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM. Sex differences in physician salary in us public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1294-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services 2016 Alpha-Numeric HCPCS File. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets/Alpha-Numeric-HCPCS-Items/2016-Alpha-Numeric-HCPCS-File.html. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 16.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Rosenthal GE. Differences in mortality and use of revascularization in black and white patients with acute MI admitted to hospitals with and without revascularization services. JAMA. 2007;297(22):2489-2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filice CE, Joynt KE. Examining race and ethnicity information in Medicare administrative data. Med Care. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wennberg JE, Cooper MM, Birkmeyer JD, et al. . The Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare, 1999. Hanover, NH: Health Forum Inc; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817-838. doi: 10.2307/1912934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. 2012;12(2):308-331. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS Employers. Guidance on the appointment and employment of NHS locum doctors. http://www.nhsemployers.org/~/media/Employers/Publications/Guidance-on-the-appointment-and-employment-of-locum-doctors.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2017

- 23.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare claims processing manual. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/downloads/clm104c01.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2017.

- 24.Huckman RS, Pisano GP. The firm specificity of individual performance: evidence from cardiac surgery. Manage Sci. 2006;52(4):473-488. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.1050.0464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Curry L, et al. . Variation in hospital mortality rates for patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(8):1108-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah B, Hernandez AF, Liang L, et al. ; Get With The Guidelines Steering Committee . Hospital variation and characteristics of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in patients with heart failure: data from the GWTG-HF (Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure) registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(5):416-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel MR, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. . A comparison of acute coronary syndrome care at academic and nonacademic hospitals. Am J Med. 2007;120(1):40-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jennison T. Locum doctors: patient safety is more important than the cost. Int J Surg. 2013;11(10):1141-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietz AS, Pronovost PJ, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. . A systematic review of teamwork in the intensive care unit: what do we know about teamwork, team tasks, and improvement strategies? J Crit Care. 2014;29(6):908-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mills P, Neily J, Dunn E. Teamwork and communication in surgical teams: implications for patient safety. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):107-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Leary KJ, Sehgal NL, Terrell G, Williams MV; High Performance Teams and the Hospital of the Future Project Team . Interdisciplinary teamwork in hospitals: a review and practical recommendations for improvement. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(1):48-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hackman JR. Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huckman RS, Staats BR, Upton DM. Team familiarity, role experience, and performance: evidence from Indian software services. Manage Sci. 2008;55(1):85-100. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lowes R. Locum tenens: when you need one, how to get one. Med Econ. 2007;84(9):38–, 40, 42 passim.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan PS, et al. . Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(6):587-593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsugawa Y, Jha AK, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM, Jena AB. Variation in physician spending and association with patient outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):675-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staff Care Survey of nurse practitioners: practice trends and perspectives. https://www.staffcare.com/Pages/ResourceDetails.aspx?id=371. Accessed November 3, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients After Adjustment for Hospital Fixed Effects.

eTable 2. Yearly Unadjusted and Adjusted 30-Day Mortality Among Hospitalized Patients Treated by Locum and Non–Locum Tenens Physicians, Overall and by Tercile of Locum Tenens Intensity.

eTable 3. Characteristics of Hospitalized Patients After Adjustment for Physician Fixed Effects.

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses Evaluating Adjustment for Physician Fixed Effects and Use of a Linear Probability Model.