Abstract

Introduction

The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) required major revisions to food packages in 2009; effects on nationwide low-income household purchases remain unexamined.

Methods

This study examines associations between WIC revisions and nutritional profiles of packaged food purchases from 2008 to 2014 among 5,352 low-income households with preschoolers in the U.S. (WIC participating versus nonparticipating) utilizing Nielsen Homescan Consumer Panel data. Overall nutrients purchased (e.g., calories, sugar, fat), amounts of select food groups with nutritional attributes that are encouraged (e.g., whole grains, fruits and vegetables) or discouraged (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages, candy) consistent with dietary guidance, and composition of purchases by degree of processing (less, moderate, or high) and convenience (requires preparation, ready to heat, or ready to eat) were measured. Data analysis was performed in 2016. Longitudinal random-effects model adjusted outcomes controlling for household composition, education, race/ethnicity of the head of the household, county quarterly unemployment rates and seasonality are presented.

Results

Among WIC households, significant decreases in purchases of calories (−11%), sodium (−12%), total fat (−10%), and sugar (−15%) occurred, alongside decreases in purchases of refined grains, grain-based desserts, higher-fat milks, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and increases in purchases of fruits/vegetables with no added sugar/fats/salt. Income-eligible nonparticipating households had similar, but less pronounced, reductions. Changes were gradual and increased over time.

Conclusions

WIC food package revisions appear associated with improved nutritional profiles of food purchases among WIC participating households compared with low-income nonparticipating households. These package revisions may encourage WIC families to make healthier choices among their overall packaged food purchases.

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) served more than 8 million low-income people,1 including pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding women, children up to age 5 years, and 53% of all infants born in the U.S.2 WIC supplements the diets of these populations with nutritious foods, and provides breastfeeding promotion and support, nutrition education and counseling, and healthcare referrals.2 WIC food packages are based on participant age and developmental status, and for women and children include milk, eggs, cereals, whole grains, legumes, and juice. Since WIC’s inception in 1972, WIC food packages remained largely unchanged until 2007 interim rules required substantial revisions to be implemented by October 2009.3 These revisions aimed to improve variety and flexibility in WIC food packages and align them with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics infant feeding guidelines.3 Revisions included new foods such as whole-grain bread, fruits and vegetables, and whole-grain cereals; addition of fruit and vegetable cash value vouchers; reductions in milk, juice, egg, and cheese; and a switch from whole milk to 2% milk for children aged 2 or more years and women.3

Regional studies examining changes in food availability or access following WIC policy updates found the healthfulness of available foods improved after implementation.4–11 Studies of self-reported intake in California, New York, New Mexico, and Chicago, Illinois found WIC revisions associated with significant shifts from higher- to lower-fat milk and increased intake of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables.12–17 A cross-sectional study by Tester et al.18 used 2003– 2008 and 2011–2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data to find whether WIC revisions were associated with higher dietary quality for WIC participants compared with nonparticipants.18

However, few studies have examined associations between WIC package revisions and nutritional profiles of overall food purchases. Previous research has found WIC purchases represent 5%–18% of total food expenditures for WIC participating households, so understanding how WIC package revisions relate to nutritional profiles of all household food purchases is important.19 WIC participants could use non-WIC dollars to purchase less-healthy items, potentially mitigating the nutritional impact of the WIC package on overall diet. Also, WIC provides nutrition education and food packages for individual participants, WIC participation may affect nonparticipating household members, by increasing healthy food availability at home, even for nonparticipants. One recent study examining overall purchases by low-income shoppers using WIC benefits before and shortly after the interim revisions in two New England states found improvement in healthfulness of purchases (measured by saturated fat, sugar, and sodium) by WIC-participating shoppers, particularly for beverages.20 However, because of the study’s limited post-revision period and geographic scope, it is unclear if improved purchase patterns persist or are generalizable to other areas.

Current literature also lacks evaluation of whether increased emphasis on certain food groups from the revised WIC packages relates to an improved nutritional profile of overall purchases. It remains unknown whether WIC participation is associated with decreased purchases of convenient ready-to-heat and ready-to-eat foods, which are generally not included among foods provided in WIC packages and tend to have higher sugar, saturated fat, and sodium compared with foods requiring cooking/preparation.21

This study examines household food purchases across the U.S. from 2008 to 2014 to explore changes in packaged food and beverage purchases (PFP) among WIC participating and nonparticipating households, all WIC-income-eligible (≤185% of the U.S. Poverty Income Guidelines), with any child aged 1–4 years. For all WIC-income-eligible households, PFP make up approximately 70% of calories consumed, according to analyses of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2012 data (author’s own calculations).22 PFP include measures of select food groups with nutritional attributes that are encouraged (e.g., whole grains, fruits and vegetables) or discouraged (e.g., sugar-sweetened beverages [SSBs], candy) consistent with dietary recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics, nutrients purchased (calories, sodium, fat, saturated fat, sugar, protein, fiber), as well as degree of processing and convenience. This study is the first major effort to quantify how WIC package revisions relate to PFP among low-income households and if these revisions are associated with differences in the nutrients obtained from packaged food items between WIC and non-WIC households nationally.

METHODS

Study Sample

The primary data source is the 2008–2014 Nielsen Homescan Panel, a nationwide sample of up to 65,000 households sampled each year that record all PFP from stores using scanners or smartphone applications.23 Sociodemographic information collected annually includes state and county of residence, household composition, nominal income, education and race/ethnicity of the head of household, age and gender of all household members, and household sampling weights. Homescan data are used by researchers, particularly agricultural and marketing economists, to analyze food demand, consumption, branding, and promotion strategies.24–27 Several studies investigating the representativeness of Homescan data from 2008 reported some sample selection and participation biases,28 which can be adjusted for using household demographics.26

The sample in this study was limited to households that included at least one child aged 1 to 4 years and were WIC-income-eligible based on household size and inflation-adjusted Federal Poverty Levels (household income ≤185% Federal Poverty Level),29 with criteria applied for each year of data (N=5,520 households; N=21,449 household-quarter observations). Nielsen administered a quarterly online survey (every 3 months) asking the female head of household if she received WIC benefits currently, previously but not currently, or never. A household is identified as WIC for each quarter based on their response. Observations were excluded for inconsistent reporting (“participated in WIC” one quarter, then “never participated” in later quarter [n=230]) or missingness (n=7,623). The final analytic sample included 12,035 household-quarter observations from 4,537 households for the three time periods of interest: January 2008–September 2009 (pre-revision period, 7 quarters); January 2010–September 2011 (early-revision period, 7 quarters); and January 2013–September 2014 (late-revision period, 7 quarters). A participant flow diagram with further detail is available in Appendix Figure 1.

Nutrition Facts Label data are the nutrition data found on food labels. Label information on all macronutrients, other vitamins and minerals, and ingredients30 from products with barcodes were obtained from several commercial sources described in detail elsewhere31 and matched by barcode to Homescan purchases. Data is limited to barcoded products; therefore, this excludes random-weight meats, deli salads, or loose fresh produce.

Quarterly unemployment rates were derived from the average unemployment rate for the 3 months of each quarter from 2008 to 2014 using the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics (www.bls.gov/lau) for each county where the Homescan respondent resided; unemployment rates were included as a proxy for the economic climate following accepted approaches by economists.32,33 Homescan measures of employment status for the head of the household were not included in the analyses to avoid endogeneity bias from unmeasured characteristics affecting both food purchases and employment decisions (e.g., preferences, illness), and because it is unlikely that the aggregate effects of economic conditions are fully mediated by an individual’s own employment status.

Measures

The nutrient content and amount purchased for each product were used to determine the nutritional profile of PFP reported purchased in terms of energy (kcals/capita/day), total sugar (g/capita/day), saturated fat (g/capita/day), total fat (g/capita/day), sodium (mg/capita/day), protein (g/capita/day), and fiber (g/capita/day) purchased by the household during each quarter for total PFP.

The current study focused on food and beverage groups issued to the majority of WIC participants, which underwent changes in the food package revisions, or food and beverage groups that the WIC program seeks to encourage and those that encouraged items may replace (e.g., whole versus refined grains). Amounts purchased of each food or beverage group (g/capita/day) were calculated for each time period.

More than 420,000 food and beverage items reported as purchased by the Homescan panel were reviewed by a team of Registered Dietitians and classified into selected mutually exclusive food and beverage groups using product attributes and Nutrition Facts Label information including ingredients and macronutrients. Purchased items were also classified as “WIC eligible” or “WIC ineligible” based on WIC nutrition standards outlined in 7 CFR Part 246.10.34 This classification means the item meets WIC nutrition standards, but does not indicate that it is WIC approved and covered under WIC benefits, as each State Agency determines which items are WIC approved for participants in that particular State Agency. Products missing Nutrition Facts Label information needed for WIC classification were flagged as “unable to determine WIC status” and treated separately during analysis.

All unique food and beverages products (N=617,779), beyond the previously defined food groups of interest, were classified into three categories based on the degree of industrial food processing (less processed, moderately processed, and highly processed), and convenience of preparation (requires cooking or preparation, ready to heat, and ready to eat) based on a system previously described and published.21 Programming algorithms assigned each barcoded product into a category for processing and for convenience using methods explained in detail elsewhere.21

Appendix Table 1 lists select food groups of interest with specifications for WIC eligibility, specific examples of foods in each group, and how these examples were classified based on degree of processing and convenience.

Statistical Analysis

Given the panel nature of the data, longitudinal random-effects models were applied at the household-quarter level to predict the outcomes of interest among WIC versus non-WIC households during each of the three time periods. Models adjusted for household composition (number of household members of each age group and sex), education, race/ethnicity of the head of the household, county unemployment rate, state of residence, and quarter (to address seasonality in purchases). SEs were corrected with clustering by households.

Key covariates of interest include household WIC status (reference: non-WIC), time period (reference: pre-revision), and the interaction of WIC status with time. The coefficient of the interactions between the WIC status and the early-revision or late-revision time periods indicates the association of WIC participation with the nutritional outcome in question, above and beyond any secular trends (e.g., a difference-in-difference approach). Analyses were Bonferroni-adjusted for multiple comparisons. All analyses were conducted in 2016, using Stata, version 13.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of household and contextual measures by WIC status during the three periods. WIC- and non-WIC low-income households did not differ significantly.

Table 1.

Household and Contextual Characteristics in the Nielsen Homescan Panel During Pre-revision, Early-revision, and Late-revision Periods

| Pre-revision (N=1,818) | Early-revision (N=1,540) | Late-revision (N=1,275) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIC (N=852) |

Non-WIC (N=966) |

WIC (N=716) |

Non-WIC (N=824) |

WIC (N=587) |

Non-WIC (N=688) |

|||||||

| Characteristics | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE |

| Total | 50.02 | 1.58 | 49.98 | 1.58 | 51.02 | 1.74 | 48.98 | 1.74 | 52.04 | 1.76 | 47.96 | 1.76 |

| Race, % | p=0.31 | p=0.9 | p=0.008 | |||||||||

| Hispanic | 19.58 | 2.01 | 19.02 | 1.92 | 16.8 | 2.03 | 16.17 | 1.98 | 24.46 | 2.39 | 14.83 | 1.99 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 67.28 | 2.22 | 64.56 | 2.2 | 65.14 | 2.44 | 65.02 | 2.41 | 57.1 | 2.57 | 65.92 | 2.42 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 10.54 | 1.4 | 11.69 | 1.46 | 13.11 | 1.71 | 12.67 | 1.7 | 11.9 | 1.7 | 13.65 | 1.75 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 2.6 | 0.64 | 4.73 | 0.91 | 4.95 | 1.09 | 6.14 | 1.11 | 6.53 | 1.23 | 5.6 | 1.07 |

| Education, % | p=0.0005 | p=0.84 | p=0.74 | |||||||||

| <High school | 4.2 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 0.4 | 4.15 | 1 | 3.09 | 0.89 | 4.16 | 1.06 | 4.11 | 1.05 |

| Graduated high school | 33.55 | 2.15 | 29.65 | 2.08 | 28.8 | 2.28 | 31.53 | 2.28 | 24.46 | 2.67 | 20.79 | 2.09 |

| Some college | 38.68 | 2.21 | 37.89 | 2.16 | 39.29 | 2.44 | 38.73 | 2.41 | 41 | 2.52 | 44.86 | 2.44 |

| Graduated college | 21.45 | 1.78 | 26.34 | 1.92 | 28.89 | 2.04 | 22.46 | 1.97 | 24.22 | 2.02 | 23.96 | 1.92 |

| Post college grad | 2.12 | 0.57 | 4.97 | 0.88 | 3.86 | 0.84 | 4.19 | 0.93 | 6.15 | 1.1 | 6.28 | 1.02 |

| Household composition | ||||||||||||

| # children <1 year | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| # children 1– 4 years | 1.26 | 0.02 | 1.2 | 0.02 | 1.3 | 0.03 | 1.25 | 0.02 | 1.2 | 0.02 | 1.17 | 0.02 |

| # females 5– 11 years | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 0.49 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.03 |

| # males 5–11 years | 0.45 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.03 | 0.42 | 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.03 |

| # females 12–18 years | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| # males 12– 18 years | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| # females 19–50 years | 1.06 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.02 | 1.1 | 0.02 | 1.15 | 0.02 | 1.08 | 0.02 | 1.04 | 0.02 |

| # males 19– 50 years | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.03 |

| # females >50 years | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.02 |

| # males >50 years | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.02 |

| County unemployment rate | 7.56 | 0.14 | 7.43 | 0.14 | 10.16 | 0.14 | 10.44 | 0.16 | 7.4 | 0.12 | 7.3 | 0.1 |

Source: Authors’ own calculation based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2008–2014 periods, for the U.S. market (The Nielsen Company, 2015).

Notes: p-values are for testing whether there is statistical significance between WIC and non-WIC households within each period.

WIC, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

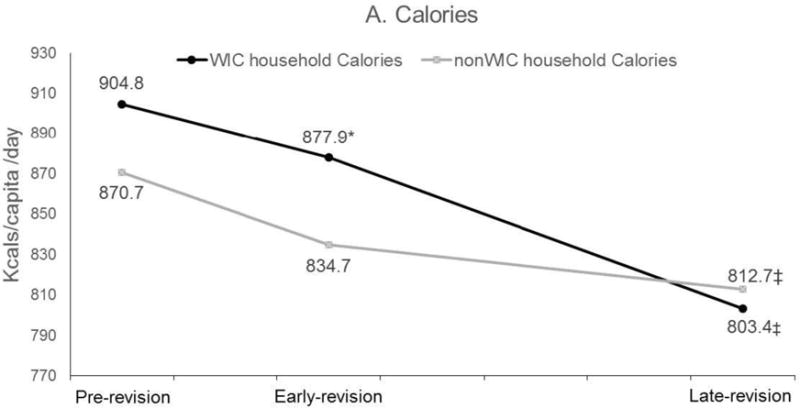

Figure 1 presents model-adjusted nutrients purchased per capita per day across the three periods by WIC and non-WIC households. WIC households purchased significantly fewer calories from pre-revision to late-revision (−101 kcal or an 11% decline), while non-WIC households saw a smaller, but still significant, decline of 58 kcal per capita per day (a 6% decrease; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Model adjusted nutrients purchased by WIC status during pre-revision, early-revision and late-revision periods. (A) Calories; (B) Sodium; (C) Sugar and fat.

Source: Authors’ own calculation based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2008–2014 periods, for the U.S. market (The Nielsen Company, 2015).

Notes: Longitudinal random-effects model covariates include: WIC status, time periods, interactions between WIC status and time-period household composition (number of household members of each age group and sex), education, race/ethnicity of the head of the household, county unemployment rate, state dummies, quarter dummies (to address seasonality in purchases). SEs and CI corrected the SEs with clustering by households. * indicates statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between WIC and non-WIC households within each period at p<0.006. † denotes statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between early-revision period and pre-revision period within each WIC status at p<0.006. ‡ denotes statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between late-revision period and pre-revision period within each WIC status at p<0.006.

This and subsequent results uses October 2009 as the cutpoint for pre-revision vs post-revision. However, several states implemented the package revisions earlier as noted in Joyce and Reeder (2014). Appendix Figure 2 presents the analogous results for this figure using modified periods.

WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

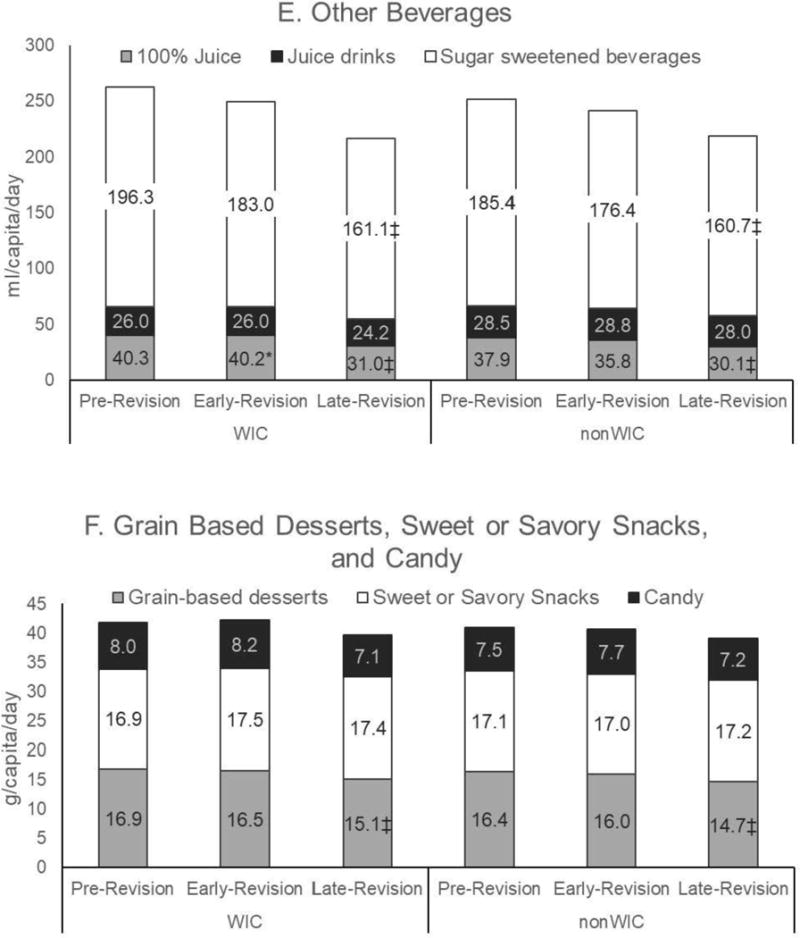

Significant per capita per day decreases from pre- to late-revision periods were found for sodium among both WIC (−212 mg or >12% decline) and non-WIC households (−202 mg or 12% decline; Figure 1B). Total sugar purchased by WIC households declined by 10 g per capita per day (14.75%; Figure 1C), mostly attributable to a significant decrease in purchases of SSBs (Figure 2E). Non-WIC households had a smaller decrease (−6 g or 10%). Total fat purchased decreased by 4 g (10%) and 2 g (5%) per capita per day among WIC and non-WIC households, respectively (Figure 1C), largely because of a decline in purchases of higher-fat milks (Figure 2D). No clinically significant changes were found for protein or fiber.

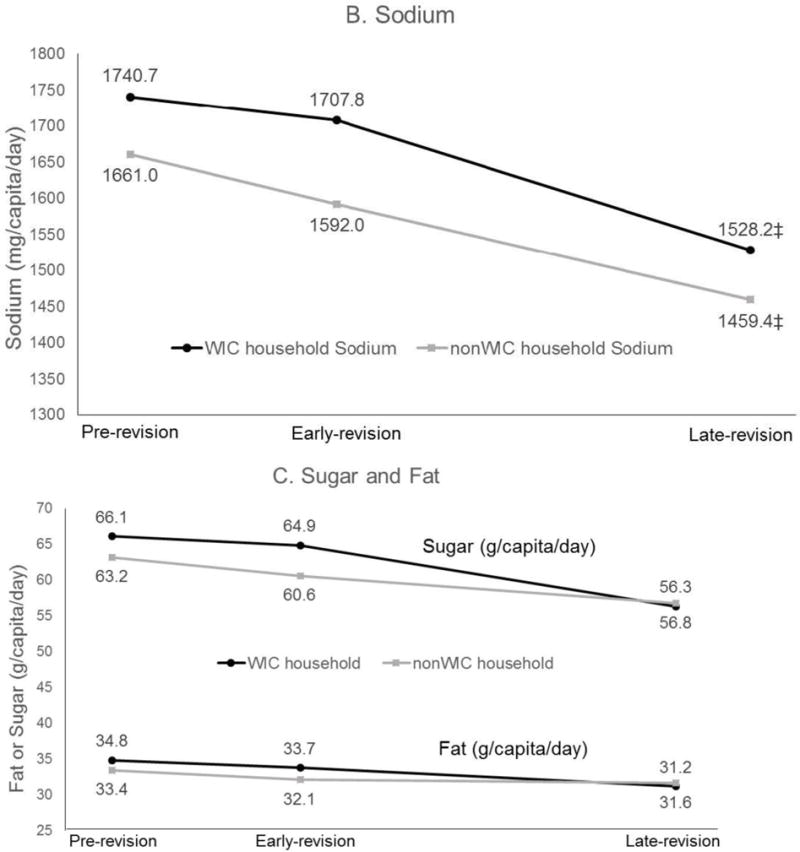

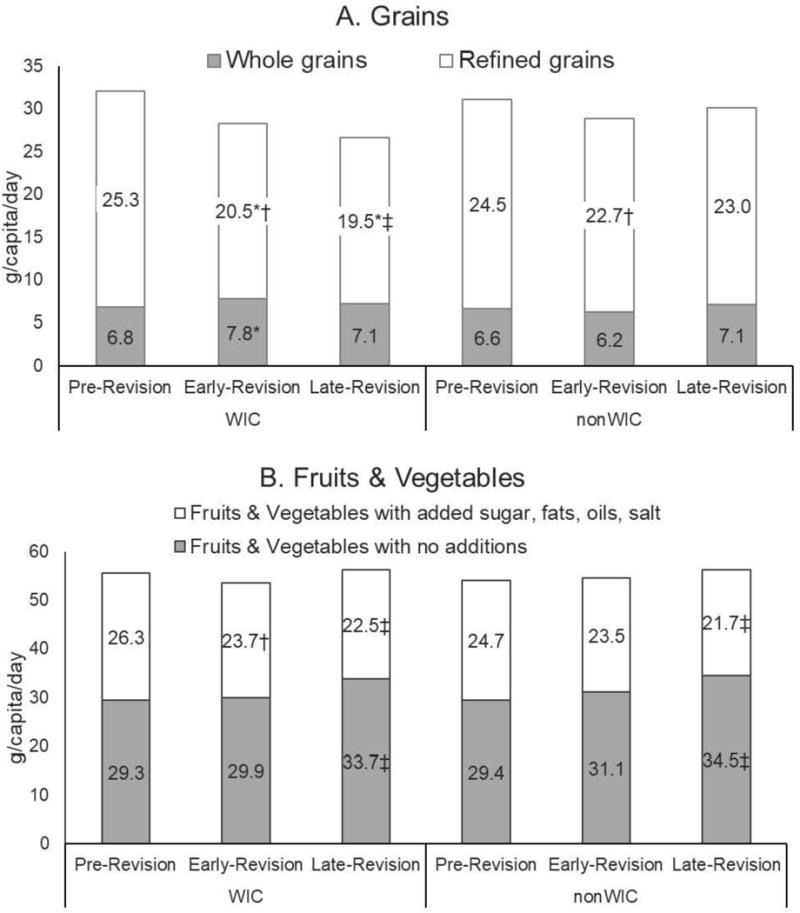

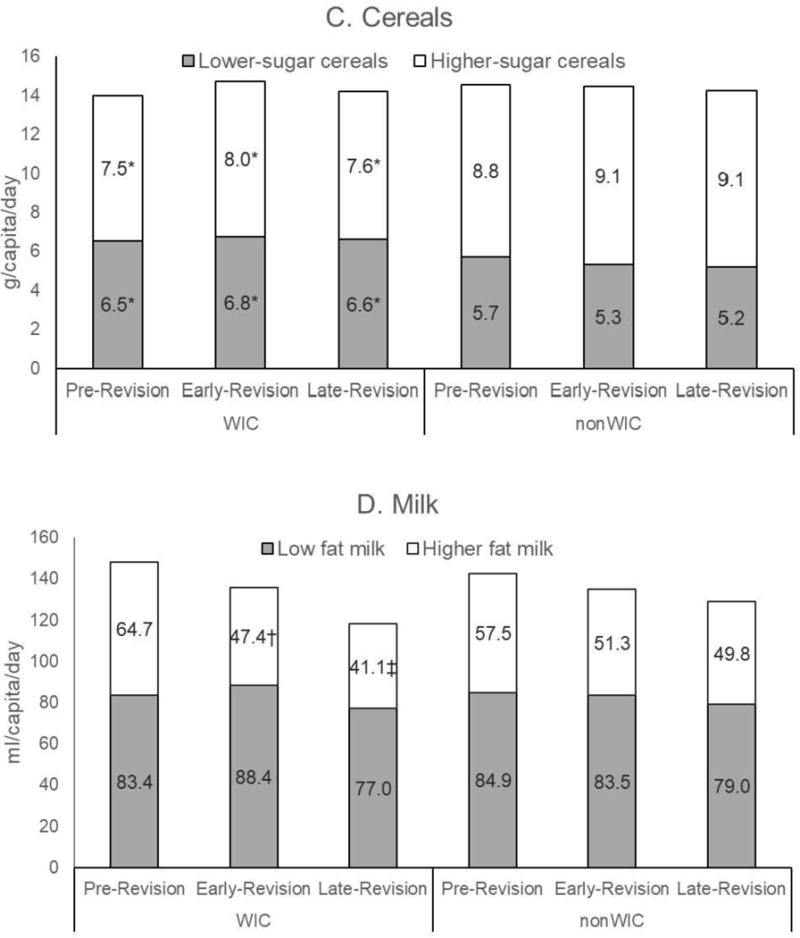

Figure 2.

Model adjusted purchases of select food groups by WIC status during the pre-revision, early-revision, and late-revision periods. (A) Grains; (B) Fruits and vegetables; (C) Cereals; (D) Milks; (E) Other beverages; (F) Grain-based desserts, sweet or savory snacks, and candy.

Source: Authors’ own calculation based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2008–2014 periods, for the U.S. market (The Nielsen Company, 2015).

Notes: Longitudinal random-effects model covariates include: WIC status, time periods, interactions between WIC status and time-period household composition (number of household members of each age group and sex), education, race/ethnicity of the head of the household, county unemployment rate, state dummies, quarter dummies (to address seasonality in purchases). SEs and CI corrected the SEs with clustering by households. * indicates statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between WIC and non-WIC households within each period at p<0.006. † indicates statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between early-revision period and pre-revision period within each WIC status at p<0.006. ‡ indicates statistical significance, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, compared to difference between late-revision period and pre-revision period within each WIC status at p<0.006. Data is limited to products with barcodes, therefore excludes some random weight meats, deli salads, or loose fresh fruits or vegetables.

WIC, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

There were no significant differences between WIC and non-WIC households in nutrients purchased in pre- or post-revision periods.

Among food groups, there were no significant increases in purchases of whole grain items (i.e., breads, rice, tortillas), but a significant decline in per capita daily purchases of refined grain items for WIC households (−6 g or 23%; Figure 2A).

Figure 2B indicates that both WIC and non-WIC households purchased more fruits and vegetables meeting WIC standards over time, possibly in place of more processed fruits and vegetables. Meanwhile, no significant change in breakfast cereal purchases was seen for either type of households, although WIC households consistently purchased more lower-sugar cereals than non-WIC households. WIC households also purchased less of the higher-sugar cereals, compared with non-WIC households (Figure 2C).

WIC households purchased 24 mL (37%) less higher-fat milk per capita per day in the late-revision period compared with pre-revision, compared with a decline of 8 mL (13%) among non-WIC households. (Figure 2D).

All households decreased their purchases of 100% juice, while purchases of juice drinks (1%– 99% juice, typically sweetened) did not change significantly over time. A large decline in purchases of SSBs was seen over time, with WIC households purchasing 35 mL (18%) less and non-WIC households purchasing 25 mL (13%) less per capita per day (Figure 2E).

No significant differences between WIC and non-WIC households were found in purchases of grain-based desserts, snacks or candy. Purchases of grain-based desserts declined for both WIC households by 1.8 g (10%) and non-WIC households by 1.7 g (10%) per capita per day. No significant changes were seen in purchases of candy or sweet or savory snacks over time (Figure 2F).

The proportion of PFP classified as highly processed was consistent across time for all households at just over 60% (Appendix Figure 3A). The proportions of less and moderately processed items were also fairly consistent across time, with only a 1% increase for all households in moderately processed items from the pre-revision to the late-revision period. No significant changes were found for degree of convenience over time or across WIC and non-WIC household purchases (Appendix Figure 3B).

The model adjusted values are shown in Appendix Tables 2 and 3. These appendices also include difference-in-difference measures as summarized in Table 2. WIC households had a larger increase in whole grain purchases at the early-revision period, but the difference did not persist. WIC households had larger reductions over time for refined grains and higher-fat milks.

Table 2.

Difference-in-Difference (DID) Measures Showing Associations Between WIC-participating (Versus Non-participating) Households on Changes in Nutritional Outcomes

| DID early-revision | DID late-revision | |

|---|---|---|

| Nutritional outcome | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) |

| Nutrients purchased (capita/day) | ||

| Calories (kcals) | 9.1 (−27.4, 45.6) | −43.4 (−89.7, 2.9) |

| Sodium (mg) | 36.1 (−76.6, 148.9) | −10.8 (−145.5, 123.9) |

| Total fat (g) | 0.3 (−1.3, 1.8) | −1.8 (−3.8, 0.1) |

| Saturated fat (g) | 2.8 (0.4, 5.2) | −0.9 (−3.5, 1.8) |

| Sugar (g) | 1.4 (−1.7, 4.5) | −3.3 (−7.3, 0.6) |

| Protein (g) | 0.4 (−0.8, 1.5) | −0.7 (−2.2, 0.7) |

| Fiber (g) | 0.2 (−0.1, 0.5) | −0.2 (−0.6, 0.2) |

| Select food groups (g/capita/day) | ||

| Breads, rice, tortillas | ||

| Whole grainsa | 1.4 (0.4, 2.4) | −0.2 (−1.3, 1.0) |

| Refined grainsb | −3.0 (−4.6, −1.4) | −4.3 (−6.2, −2.3) |

| Fruits and vegetables (FV) | ||

| FV with no additionsa | −1.1 (−3.5, 1.4) | −0.7 (−3.8, 2.4) |

| FV with added sugar, fats, oils, saltb | −1.3 (−3.2, 0.6) | −0.7 (−3.0, 1.6) |

| Cereals | ||

| Lower-sugara | 0.6 (0.0, 1.2) | 0.6 (−0.1, 1.3) |

| Higher-sugarb | 0.2 (−0.6, 1.0) | −0.1 (−1.1, 0.8) |

| Milk | ||

| Lower-fat milka | 6.5 (−0.8, 13.8) | −0.5 (−9.8, 8.9) |

| Higher-fat milkb | −11.1 (−18.9, −3.3) | −15.9 (−25.7, −6.1) |

| Other beverages | ||

| 100% juicea | 2.1 (−1.3, 5.5) | −1.4 (−5.8, 2.9) |

| Juice drinksb | −0.3 (−4.0, 3.4) | −1.3 (−5.7, 3.2) |

| SSBsb | −4.3 (−19.8, 11.1) | −10.5 (−30.1, 9.1) |

| Dessert, snacks, candy | ||

| Grain based dessertsb | 0.1 (−1.1, 1.3) | 0.0 (−1.5, 1.5) |

| Savory or sweet snacksb | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.7) | 0.3 (−1.0, 1.7) |

| Candyb | 0.1 (−0.7, 0.9) | −0.6 (−1.6, 0.4) |

| Degree of processing or convenience, % | ||

| Processing | ||

| Less | −0.4 (−1.3, 0.5) | −0.9 (−2.1, 0.2) |

| Moderate | 0.5 (−0.1, 1.0) | 0.3 (−0.3, 1.0) |

| High | −0.1 (−1.0, 0.9) | 0.5 (−0.7, 1.7) |

| Convenience | ||

| Ready-to-eat | 0.1 (−0.8, 1.0) | 0.4 (−0.7, 1.5) |

| Ready-to-heat | 0.0 (−0.7, 0.6) | −0.2 (−0.9, 0.6) |

| Requires preparation | −0.2 (−1.0, 0.6) | −0.2 (−1.2, 0.7) |

Source: Authors’ own calculation based in part on data reported by Nielsen through its Homescan Services for all food categories, including beverages and alcohol for the 2008–2014 periods, for the U.S. market (The Nielsen Company, 2015).

Notes: Boldface indicates statistical significance compared to difference between WIC and non-WIC households at pre-revision period, accounting for Bonferroni corrections, at p<0.006.

indicates “WIC Eligible” products meeting WIC nutritional standards based on 7 CFR Part 246.10.

indicates “WIC ineligible” products not meeting WIC nutrition standards. Longitudinal random-effects model covariates include: WIC status, time periods, interactions between WIC status and time-period household composition (number of household members of each age group and sex), education, race/ethnicity of the head of the household, county unemployment rate, state dummies, quarter dummies (to address seasonality in purchases). SEs and CI corrected the SEs with clustering by households.

SSBs, Sugar sweetened beverages; WIC, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Although nonsignificant, greater reductions over time were also found for purchased 100% fruit juices, fruit drinks, SSBs, and candy, as well as calories, sugar, fat, and sodium.

DISCUSSION

WIC package revisions were associated with significant improvements in the nutritional profiles of packaged food and beverage purchases (PFP) over time among WIC-income-eligible households with young children across the U.S. Between the pre-revision and late-revision time periods, the foods WIC-participating households purchased contained significantly less energy, sodium, fat, and sugar. In the late-revision period, WIC households purchased 212 mg less sodium and over 9.8 g less sugar per capita per day compared with the pre-revision period, representing large declines of more than 9% and 30% of the recommended daily intake for adults (or more than 9% and 60% of the recommended daily intake for preschoolers).

Additionally, WIC-participating households significantly decreased purchases of refined grain breads/rice/tortillas, grain-based desserts, higher-fat milks, and SSBs over time, while also significantly increasing purchases of fruits and vegetables with no additions, and moderately processed PFP. Non-WIC households also had reductions in purchased calories, sodium, fat, sugar, grain-based desserts, and SSBs, but these declines were less pronounced than for WIC households. The difference-in-difference analyses showed that accounting for secular trends, WIC-participating households had more significant reductions over time for refined grains and higher-fat milks.

The current findings between pre-revision to early-revision periods are consistent with an earlier study that utilized Nielsen Homescan data from 2008 to 2010 and focused on whole-grain purchases,35 as well as previous research using retailer scanner data from a grocery store chain in two New England states (Connecticut and Massachusetts) until 2010, which reported early WIC package revisions were associated with increased purchases of whole grains,15 decreased purchases of juice and soft drinks,36 decreased whole milk and cheese purchases,16 and improved overall healthfulness of purchases by households participating in WIC.20 The current study indicates similar changes in purchases during the early-revision period, with increased purchases of whole grains and decreased purchases of refined grains, juice, SSBs, and higher-fat milk.

Among research that focuses only on WIC participants, the results presented here support growing evidence that WIC package revisions are associated with higher consumption of whole grains and fruits, lower consumption of higher-fat milk and fruit juice for both children and caregivers,12 and higher overall diet quality for children.18 These nutrition improvements highlight how updating policies can meaningfully influence not just WIC participants themselves, but also their families, given changes in household purchases.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include omission of information on items purchased without barcodes, such as loose fruits and vegetables, cut-to-order meats or cheeses, or bulk grains or nuts, which limits the understanding of the implications of new cash value vouchers benefits. Also, the self-reported nature of these purchase data may result in potential biases, but the consistent findings relative to retail-based sales data suggest that this is not systematic. These data are also based on purchases, with the expectation that healthier purchases reflect healthier diets. A known limitation within WIC research is the challenge of selection into WIC participation, particularly because valid instruments in the data are extremely rare37,38 and does not exist in this case; thus, this study is unable to adequately account for potential selection into WIC participation. Moreover, for this analysis the authors have the added issue of the non-randomness of missing WIC status, which they tried to address by controlling for observed characteristics on which missingness appears to be based. Also, the survey does not assess duration of WIC participation, another limitation. Lastly, as several previous studies have identified an increase in healthy food availability in stores following the WIC food package revisions, it is difficult to isolate the effects of the WIC food package change to only WIC-participating shoppers.

Major strengths of this study include using longitudinal data with repeated measures on packaged food purchases from all retail sources (grocery stores, convenience stores, and warehouse stores) for low-income households across the contiguous U.S. over a relatively long period of time, compared with earlier studies. These allow determination of longer-term implications of the WIC package revisions in a more generalizable manner. As the WIC program considers further revisions based on the January 2017 report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine,39 continued evaluation of WIC household purchases will be useful to determine effects of further modifications.

CONCLUSIONS

Revisions to the WIC food packages since 2009 were intended to improve nutritional outcomes, among other goals.40,41 The findings presented here suggest progress towards the nutritional goals for households across the U.S.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study comes from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation via Healthy Eating Research (Grant #73247) and the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. WIC National Level Annual Summary. 2015 Mar; www.fns.usda.gov/pd/wic-program.

- 2.Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. About WIC: WIC at a Glance. 2015 Mar; www.fns.usda.gov/wic/about-wic-wic-glance.

- 3.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC Food Packages Interim Rule. Vol 72007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Malley K, Luckett BG, Dunaway LF, Bodor JN, Rose D. Use of a new availability index to evaluate the effect of policy changes to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) on the food environment in New Orleans. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(01):25–32. doi: 10.1017/S1368980014000524. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980014000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier A, McLaughlin J, Cannuscio CC, Chilton M, Krasny S, Karpyn A. The impact of WIC food package changes on access to healthful food in 2 low-income urban neighborhoods. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.08.004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Havens EK, Martin KS, Yan J, Dauser-Forrest D, Ferris AM. Federal nutrition program changes and healthy food availability. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(4):419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Middleton AE, Long MW, Schwartz MB. Positive Influence of the Revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children Food Packages on Access to Healthy Foods. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(6):850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu W, McKyer ELJ, Dowdy D, et al. Evaluating the Influence of the Revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Food Allocation Package on Healthy Food Availability, Accessibility, and Affordability in Texas. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(2):292–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stallings TL, Gazmararian JA, Goodman M, Kleinbaum D. Agreement between the Perceived and Actual Fruit and Vegetable Nutrition Environments among Low-Income Urban Women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(4):1304–1318. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2015.0109. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2015.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb LK, Anderson CAM, Appel L, et al. Baltimore City Stores Increased The Availability of Healthy Food After WIC Policy Change. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1849–1857. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0632. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose D, O’Malley K, Dunaway LF, Bodor JN. The Influence of the WIC Food Package Changes on the Retail Food Environment in New Orleans. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2014;46(3 suppl):S38–S44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.01.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whaley SE, Ritchie LD, Spector P, Gomez J. Revised WIC food package improves diets of WIC families. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(3):204–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2011.09.011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiasson MA, Findley S, Sekhobo J, et al. Changing WIC changes what children eat. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(7):1423–1429. doi: 10.1002/oby.20295. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odoms-Young AM, Kong A, Schiffer LA, et al. Evaluating the initial impact of the revised Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) food packages on dietary intake and home food availability in African-American and Hispanic families. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(01):83–93. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000761. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013000761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J. Federal Food Package Revisions: Effects on Purchases of Whole-Grain Products. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):422–429. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Henderson KE, Schwartz MB. The Positive Effects of the Revised Milk and Cheese Allowances in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2014;114(4):622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morshed AB, Davis SM, Greig EA, Myers OB, Cruz TH. Effect of WIC Food Package Changes on Dietary Intake of Preschool Children in New Mexico. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2015;2(1):3–12. doi: 10.14485/HBPR.2.1.1. https://doi.org/10.14485/HBPR.2.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tester JM, Leung CW, Crawford PB. Revised WIC Food Package and Children’s Diet Quality. Pediatrics. 2016;137(5):e20153557. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3557. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine. Review of WIC food packages: Proposed framework for revisions: Interim report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2016. https://doi.org/10.17226/21832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreyeva T, Tripp AS. The healthfulness of food and beverage purchases after the federal food package revisions: The case of two New England states. Prev Med. 2016;91:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poti JM, Mendez MA, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Is the degree of food processing and convenience linked with the nutritional quality of foods purchased by U.S. households? Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1251–1262. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.100925. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.100925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Turning point for U.S. diets? Recessionary effects or behavioral shifts in foods purchased and consumed. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):609–616. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.072892. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.072892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng SW, Popkin BM. Monitoring foods and nutrients sold and consumed in the United States: Dynamics and challenges. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Einav L, Leibtag E, Nevo A. On the Accuracy of Nielsen Homescan Data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Einav L, Leibtag E, Nevo A. Recording discrepancies in Nielsen Homescan data: Are they present and do they matter? . Quant Market Econ. 2010;8(2):207–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-009-9073-0. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhen C, Taylor JL, Muth MK, Leibtag E. Understanding Differences in Self-Reported Expenditures between Household Scanner Data and Diary Survey Data: A Comparison of Homescan and Consumer Expenditure Survey. Rev Ag Econ. 2009;31(3):470–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9353.2009.01449.x. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aguiar M, Hurst E. Life-Cycle Prices and Production. Am Econ Rev. 2007;97(5):1533–1559. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.5.1533. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lusk JL, Brooks K. Who Participates in Household Scanning Panels? . Am J Agric Econ. 2011;93(1):226–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaq123. [Google Scholar]

- 29.DHHS. U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines used to determine financial eligibility for certain federal programs. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines. Published 2017. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 30.National Archives and Records Administration. 21 CFR 101.9. Washington, DC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slining MM, Ng SW, Popkin BM. Food companies’ calorie-reduction pledge to improve U.S. diet. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dave DM, Kelly IR. How does the business cycle affect eating habits? Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(2):254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colman G, Dave D. Exercise, physical activity, and exertion over the business cycle. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costa SMM, Horta PM, Santos LCd. Analysis of television food advertising on children’s programming on “free-to-air” broadcast stations in Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2013;16(4):976–983. doi: 10.1590/s1415-790x2013000400017. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2013000400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh M, Jensen HH, Rahkovsky I. Did Revisions to the WIC Program Affect Household Expenditures on Whole Grains? Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2016;38(4):578–598. https://doi.org/10.1093/aepp/ppw020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreyeva T, Luedicke J, Tripp AS, Henderson KE. Effects of reduced juice allowances in food packages for the women, infants, and children program. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):919–927. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3471. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shadish WR, Clark MH, Steiner PM. Can nonrandomized experiments yield accurate answers? A randomized experiment comparing random and nonrandom assignments. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(484):1334–1344. https://doi.org/10.1198/016214508000000733. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colman S, Nichols-Barrer IP, Redline JE, Devaney BL, Ansell SV, Joyce T. Effects of the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): A Review of Recent Research. Mathematica Policy Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Academies of Sciences Engineering, and Medicine. Review of WIC food packages: Improving balance and choice: Final report. Washington, DC: 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cole N, Jacobson J, Nichols-Barrer I, Fox MK. WIC food packages policy options study. Mathematica Policy Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC): Revisions in the WIC Food Packages Final Rule. Vol 72014. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.