Abstract

The most common benign tumor of the brain is meningiomas. Usually diagnosed between the ages of 40–60, they are more common in women. Studies have shown a strong relationship between hormones and malignancies. Although meningiomas are slow-growing tumors of the brain, pregnancy seems to induce its growth speed. Studies concerning meningiomas and hormone relationship may explain the reason why symptoms during pregnancy flare. More specifically, the estrogen and progesterone receptor may take an active role through signal transduction in inducing the growth of the tumor. Thus, the dilemma of pregnancy + meningioma arises. In this case, a 21-year-old pregnant with a giant meningioma diagnosed on the symptom of loss of sight is reported. Her pregnancy was terminated, and the tumor was excised. Her vision improved and the histopathological examination showed a progesterone receptor positive meningioma. It is a challenging decision to be made by the physician, the patient and the family when deciding if and when pregnancy should be terminated once an intracranial meningioma is diagnosed.

Keywords: Brain tumor, meningioma, pregnancy, termination, vision disorders

Introduction

Meningiomas are the most common benign and most common nonglial tumor of the brain. They are usually seen between the ages of 40–60 and are more common in postmenopausal women. 90% of meningiomas are benign, 6% are atypical, and 2% are malignant.[1] They orginate from arachnoid cap cells and may be diagnosed on symptoms or incidentally.[2] Intracranial malignancies are uncommon during pregnancy. According to Isla et al. during 12 years period, of 126,413 pregnant women 12 were diagnosed with intracranial tumors and only 2 of them were a meningioma.[3] However, it is believed that a strong relationship exists between malignancies in women and hormones.[4] Meningiomas are twice as common in women as men.[5] Meningiomas have been shown to grow faster during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and pregnancy.[6] Meningiomas have been shown to grow in size and become symptomatic during pregnancy. Among the reasons believed to flare the symptoms are water retention, engorgement of vessels, and the presence of sex hormone receptors on tumor cells leading to the growth of the tumor. Raised intracranial pressure may be misdiagnosed as hyperemesis gravidarium.[7] It is a difficult dilemma both for the physician and the patient in deciding whether the pregnancy should be terminated. Herein is described a case of a giant meningioma causing loss of sight during pregnancy.

Case Report

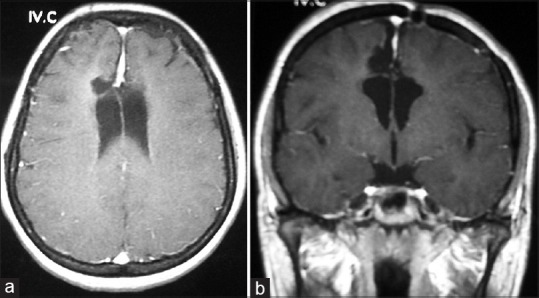

A 21-year-old female patient who had been suffering from a headache for about 2 years applied to an ophthalmologist with the loss of sight for the last 6 weeks. On her cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), an intracranial tumor had been diagnosed and was referred to the neurosurgery clinic. Her cranial MRI showed a mass measuring approximately 45 mm *70 mm at the vertex level localized within the interhemispheric fissure, T1-weighted gadolinium-enhanced MRI images showed a characteristic dural tail sign, containing perifocal edema and compressing corpus callosum and the lateral ventricles [Figure 1]. There was no history of seizures and no significant neurological examination finding in the patient except a decrease in visual acuity. Due to the fact that the patient was in her reproductive age a β–human chorionic gonadotropin analysis was ordered and found to be high (2598 mIU/ml N: 0–5,3). Being G2P1Y1 a pregnancy was possible thus she was consulted to the obstetrics and gynecology clinic. She was late to her last menstruation cycle for 5 weeks and 6 days, and her obstetric ultrasonography revealed a fundal localized gestational sac measuring approximately 6 * 8mm corresponding to a gestational age of 5 weeks. She was then evaluated multidisciplinary with a neurosurgeon, ophthalmologist, obstetrician, and anesthesiologist. With the consent of the family, her pregnancy was terminated, and the patient was transferred to our clinic.

Figure 1.

Preoperative T1-weighted gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, axial view (a) and coronal view (b) showing a large interhemispheric meningioma compressing the lateral ventricles

On her careful examination, she was found to have bilateral homonymous superior quadrantanopia. She was then operated with bifrontal craniotomy and the mass was excised totally preserving the superior and inferior sagittal sinus. She was then extubated and taken to the neurosurgery intensive care unit for postoperative follow-up period. After 24 h the surgery her neurological examination was normal, and she was transferred to the ward and discharged with no postoperative complication on the fourth day. The pathological examination of the mass was reported as meningioma WHO Grade I. On her first year follow–up, she had no symptoms, her sight had improved totally and the control cranial MRI showed no residue mass [Figure 2]. On the histological examination of the tumor, progesterone receptors were found to be positive leading to think that pre-existing asymptomatic meningiomas in women may flare during pregnancy due to increased hormone levels and become symptomatic. A year later, she became pregnant.

Figure 2.

A year after the surgery, T1-weighted gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance imaging axial view (a) and coronal view (b) showing no remnant mass

Discussion

Meningiomas which arise from arachnoid cap cells are usually found in the skull base and perivenous sinuses, where these cells are abundant. Even though most cases of meningioma are sporadic, people with neurofibromatosis-2 gene and exposure to ionizing radiation are at a higher risk.[8] However, the role of sex hormones is yet unclear. Bernard was the first to diagnose a meningioma during pregnancy in 1898.[9] The fact that intracranial meningiomas are twice as common in women as men, 10-fold increased risk of spinal meningioma in women than men, increase in the size of meningioma during pregnancy, commonly diagnosed with breast cancer in women and containing estrogen and progesterone receptors[4,10,11] leads to the conclusion that there may be a relationship with pregnancy and meningioma. These tumors tend to grow slowly however pregnancy seems to speed up this process creating symptoms.

This case presented with a bilateral homonymous superior quadrantanopia. Even though there was no direct compression of the optic chiasm, which would normally explain this defect, there are cases in the literature where parasagittal and interhemispheric meningiomas cause disturbance of the visual field.[12] The lesion in this case with a massive size compressed the ventricles superiorly causing a downward shift along with increased intracranial pressure findings such as a headache causing a probable compression of the optic chiasm or optic nerve.

80% of women and 34% of men with meningiomas were found to have progesterone receptors.[13] These receptors have been shown to take an active role in the growth of the tumor.[14] However unlike the ras system these receptors do not use a direct transcription pathway but a unique sequence activated by the binding of progesterone to its receptor.[15] Unfortunately in vitro studies have shown these receptors to disappear after 2 or 3 passages. Also, the use of anti-estrogen drugs in studies has not yielded promising results. At the same time, meningiomas have been shown to contain platelet derived growth factor,[16] vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF),[17] glucocorticoid,[18] and epidermal growth factor[19] receptors. Aside from its location, size, and venous invasion, the presence of VEGF receptors determines the length of the perifocal edema.[20] Prolactin receptors have also been found to be positive in meningiomas and closely associated with the growth rate.[21,22] Rich in prolactin receptors, meningiomas are more likely to grow during and after pregnancy causing physiological pituitary hyperplasia elevating diaphragm sellae compressing the optic nerve and chiasm causing loss of vision.

Although radiotherapy is a treatment modality, surgery is usually preferred for the treatment of meningiomas. This decision is based on symptoms, age, radiological features, postoperative morbidity, patient preference and when a definite diagnosis is necessary. For this patient, we used the Cleveland clinic Comorbidity, Localization, Age, Size, Symptoms algorithm.[23] The meningioma in our patient measured 45 mm *70 mm, contained perifocal edema and was causing visual symptoms. There is no algorithm yet present for handling meningiomas during pregnancy. After the termination of the pregnancy, surgical excision of the tumor yielded positive results. Unlike the 18 meningiomas operated during pregnancy by Kanaan et al.[7] this patient's visual symptoms improved completely after 1-year.

If a meningioma is diagnosed during pregnancy the patient herself and the age of the fetus must be evaluated first. An operation decision should be decided upon multidisciplinary taking into consideration of first the patient, second the fetus and last the decision of the family. A surgical excision without the termination of the fetus must be handled carefully, taking into consideration of intraoperative blood loss, hypotension, hypovolemia, and hypoxia. Corticosteroids may be safely used during per operative and per partum period. 2–4 mg dexamethasone every 6 h is usually the preferred choice. Since mannitol is able to pass through the maternal fetal barrier it should only be preferred under urgent conditions. Monotherapy should be the preferred therapy for seizures. It should be kept in mind that complications of seizures are more serious than the side effects of antiepileptics.[24] Women with history of seizures should take folic acid vitamin-K1 at the early stages of pregnancy to prevent the risk of neural tube defect.[25,26]

A meningioma diagnosed during pregnancy causes the surgeon to ponder whether to perform surgery immediately or wait for the end of the pregnancy. If an emergent situation is at hand, such as wide spread edema, midline shift, change in consciousness, paresis, acute hydrocephalus, or acute total neurological deficit such as loss of vision, a dual surgery may be performed where a pregnancy is terminated along with the excision of the tumor. However, if the family does not yield consent toward termination, a high risk excision of the tumor may be performed while closely monitoring the status of the fetus. However, the family should be made aware of the risks that may come along. If the surgeon has the luxury to wait for a decision in cases of tolerable symptoms such as a decrease in visual acuity, headache, vomiting, focal seizures, numbness or loss of sense of smell, the family and the physician must decide together whether to electively terminate the pregnancy and then excise the tumor.

When a benign lesion such as meningioma is diagnosed during pregnancy, if the patient is neurologically stable with no deficit a close follow-up along with MRI would be sufficient so that the pregnancy may continue through its usual course. It would be safe to suggest a C-section for the choice of birth so that valsalva maneuver would not add to the already increased intracranial pressure. The maternal health status and prognosis should be the primary area of concern when evaluating such patients. If there is a life threatening condition or a serious neurological deficit follow-up would be out of the question and the lesion must be operated on where the status of the fetus boggles the mind. The patient along with primary family relatives must be made aware of the fact that if the fetus is younger than 10–12 weeks where organogenesis is still incomplete, anesthetic agents along with anti-epileptic and anti-edema treatments may cause unwanted effects on the fetus. This should be explained in detail with all probable effects along with an obstetrician and genetic counseling where a therapeutic abortion would be advised but the decision still left to the patient and family. In cases where the fetus is older than 12 weeks and organogenesis is believed to be complete, if the obstetric examination reveals a healthy fetus a surgery along with close fetal monitoring would be proposed. In cases where fetal lung maturation is complete or new born intensive care unit is present, a 32–33 weeks pregnancy with the consent of the family and an obstetrician may undergo a dual surgery where a C-section along with the excision of the lesion would be performed.

Conclusion

Studies have shown the growth rate of meningiomas during pregnancy accelerates. However even though a strong relationship between hormones and meningiomas exists, further research must show a definite effect of hormones and hormone therapy for the treatment of these tumors. Theoretically meningiomas in women arise from differentiated arachnoid cap cells sensitive to female sex hormones. Studies up to date need to remind the surgeon that women with meningioma during their fertility period must be evaluated for pregnancy and if pregnancy is the case the patient must be evaluated multidisciplinary. If the patient suffers from increased intracranial pressure symptoms, a risk of herniation or neurological deficit, then the termination of the fetus must definitely be evaluated. Losing precious time at this critical stage in deciding whether termination should be performed may alter the benign course of meningioma causing prolonged or permanent neurological deficits. When neurological symptoms arise and if an obstetrician would not recommend otherwise, termination of the pregnancy would be more beneficial to the patient. In addition, the presence of headache, vomiting and seizure during pregnancy should not be diagnosed as hyperemesis gravidarium without a detailed neurological examination. If there is any suspicion of an intracranial tumor, abnormal fundoscopic examination, visual deficit, focal seizures or lateralizing finding a cranial MRI must be ordered.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alexiou GA, Gogou P, Markoula S, Kyritsis AP. Management of meningiomas. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiemels J, Wrensch M, Claus EB. Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 2010;99:307–14. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Isla A, Alvarez F, Gonzalez A, García-Grande A, Perez-Alvarez M, García-Blazquez M. Brain tumor and pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(96)00381-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrell UM, Adams EF, Fahlbusch R, Greb R, Jirikowski G, Prior R, et al. Hormonal dependency of cerebral meningiomas. Part 1: Female sex steroid receptors and their significance as specific markers for adjuvant medical therapy. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:743–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.5.0743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger PC, Scheithauer B, Fogel FS. Surgical Pathology of the Nervous System and Its Covering. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1991. pp. 67–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pliskow S, Herbst SJ, Saiontz HA, Cove H, Ackerman RT. Intracranial meningioma with positive progesterone receptors. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:154–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanaan I, Jallu A, Kanaan H. Management strategy for meningioma in pregnancy: A clinical study. Skull Base. 2003;13:197–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park BJ, Kim HK, Sade B, Lee JH. Meningiomas Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. Ohio: Springer; 2008. Epidemiology; pp. 11–3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard MH. Cerebral sarcoma rapidly growing during the course of pregnancy and puerperium. Bull Obstet Soc Paris. 1898;1:296–8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams EF, Schrell UM, Fahlbusch R, Thierauf P. Hormonal dependency of cerebral meningiomas. Part 2: In vitro effect of steroids, bromocriptine, and epidermal growth factor on growth of meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:750–5. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.5.0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black P, Kathiresan S, Chung W. Meningioma surgery in the elderly: A case-control study assessing morbidity and mortality. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1998;140:1013–6. doi: 10.1007/s007010050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akutsu H, Sugita K, Sonobe M, Matsumura A. Parasagittal meningioma en plaque with extracranial extension presenting diffuse massive hyperostosis of the skull. Surg Neurol. 2004;61:165–9. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carroll RS, Glowacka D, Dashner K, Black PM. Progesterone receptor expression in meningiomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1312–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carroll RS, Zhang J, Dashner K, Black PM. Progesterone and glucocorticoid receptor activation in meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:92–7. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199507000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black P, Morokoff A, Zauberman J, Claus E, Carroll R. Meningiomas: Science and surgery. Clin Neurosurg. 2007;54:91–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black PM, Carroll R, Glowacka D, Riley K, Dashner K. Platelet-derived growth factor expression and stimulation in human meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:388–93. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.3.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanaan I, Jallu A, Kanaan H. Management strategy for meningioma in pregnancy: A clinical study. Skull Base. 2003;13:197–203. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-817695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll RS. Androgen and progesterone receptors in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:635–6. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.4.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carroll RS, Black PM, Zhang J, Kirsch M, Percec I, Lau N, et al. Expression and activation of epidermal growth factor receptors in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:315–23. doi: 10.3171/jns.1997.87.2.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abe T, Black PM, Ojemann RG, Hedley-White ET. Cerebral edema in intracranial meningiomas: Evidence for local and diffuse patterns and factors associated with its occurrence. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:471–5. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll RS, Schrell UM, Zhang J, Dashner K, Nomikos P, Fahlbusch R, et al. Dopamine D1, dopamine D2, and prolactin receptor messenger ribonucleic acid expression by the polymerase chain reaction in human meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:367–75. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199602000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez-Hakim E, el-Azouzi M, Black PM. The effect of prolactin and bombesin on the growth of meningioma-derived cells in monolayer culture. J Neurooncol. 1993;16:185–90. doi: 10.1007/BF01057032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JH, Sade B. The novel “CLASS” algorithmic scale for patient selection in meningioma surgery. In: Lee JH, editor. Meningiomas: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome. London: Springer; 2009. pp. 217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomson T, Gram L, Sillanpää M, Johannessen S. Recommendations for the management and care of pregnant women with epilepsy. In: Tomson T, Gram M, Sillanpää M, Johannessen S, editors. Epilepsy and Pregnancy. Petersfield, UK: Wrighton Biomedical Publishing; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Douglas H. Haemorrhage in the new-born. Lancet. 1966;1:816–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mountain KR, Hirsh J, Gallus AS. Neonatal coagulation defect due to anticonvulsant drug treatment in pregnancy. Lancet. 1970;1:265–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90636-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]