Abstract

Background

Physician utilization of well-being resources remains low despite efforts to promote use of these resources.

Objective

We implemented a well-being assessment for internal medicine residents to improve access and use of mental health services.

Methods

We scheduled all postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) and PGY-2 residents at West Virginia University for the assessment at our faculty and staff assistance program (FSAP). While the assessment was intended to be universal (all residents), we allowed residents to “opt out.” The assessment visit consisted of an evaluation by a licensed therapist, who assisted residents with a wellness plan. Anonymous surveys were distributed to all residents, and means were compared by Student's t test.

Results

Thirty-eight of 41 PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents (93%) attended the scheduled appointments. Forty-two of 58 residents (72%, including PGY-3s) completed the survey. Of 42 respondents, 28 (67%) attended the assessment sessions, and 14 (33%) did not. Residents who attended the sessions gave mean ratings of 7.8 for convenience (1, not convenient, to 9, very convenient), and 7.9 for feeling embarrassed if colleagues knew they attended (1, very embarrassed, to 9, not embarrassed). Residents who attended the assessment sessions reported they were more likely to use FSAP services in the future, compared with those who did not attend (P < .001).

Conclusions

Offering residents a well-being assessment may have mitigated barriers to using counseling resources. The majority of residents who participated had a positive view of the program and indicated they would return to FSAP if they felt they needed counseling.

Introduction

Resident physician wellness and prevention of burnout has become an area of concern and considerable research. A 2015 meta-analysis published in JAMA estimated that the prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among physicians in training is 29%.1 There is also an increased rate of suicide for physicians in practice, compared with the general population, and physicians who experience mental health issues and burnout are less likely to seek treatment.2,3 Previously published interventions that addressed mental health and suicide prevention programs for medical residents had utilization rates between 12% and 25%, raising concerns that trainees may not be taking advantage of those resources.4–6 Commonly cited barriers to physicians seeking help include time constraints, treatment cost, concerns about confidentiality, perceived stigma, and concerns about problems with obtaining a license or hospital privileges.2–6

Making residents comfortable with seeking out mental health services is an integral part of preventing burnout and suicide and ensuring well-being. There is a paucity of literature regarding effective strategies for mitigating barriers and increasing utilization of mental health services. At our institution, a faculty and staff assistance program (FSAP) offered mental health evaluation and counseling. We wanted to explore the impact of a universal assessment on an entire resident cohort. Prior to our intervention, only residents going through remediation, and those in obvious crisis, were required by their program to go for an evaluation.

To increase residents' use of counseling services through FSAP, we implemented a universal well-being assessment, with an “opt out.” By scheduling all residents for the evaluation, we sought to reduce the stigma of seeking out mental health services. We also aimed to decrease concerns about time and convenience by scheduling a wellness day to allow residents to attend the session. The visit was intended to familiarize trainees with FSAP services before a crisis arose, so they would feel comfortable accessing this resource as needed. Outcomes of this study focused on resident attendance and attitudes toward FSAP.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Our well-being assessment was initiated at the start of the 2015–2016 academic year. Participants were all postgraduate year 1 (PGY-1) and PGY-2 internal medicine residents at West Virginia University, a medium-sized academic program.

Intervention

Permission for the wellness assessment was obtained from department leadership and the graduate medical education office. The FSAP program was already in place as a service to all faculty and employees at the institution. Internal funding ($20,000; $488/resident/y) was obtained to ensure availability of appointments and guarantee prompt follow-up. During the first year of implementation, only interns were included in the program, and they were informed about the program during orientation. During the second year, PGY-2 residents were continued in the program along with the incoming PGY-1 class. Appointments were scheduled by either the program administrator or the chief residents during outpatient or elective time, and residents were notified in advance. The entire day was considered a “wellness day,” and the residents who participated were not required to report to work and were not charged a vacation day or a personal/sick day. The project was initiated as program educational improvement.

Interns were scheduled for 2 visits per year, 1 in late fall and again in late winter. The PGY-2s were scheduled 1 time in the winter. PGY-3s were not included in the intervention but did have the option of scheduling a wellness assessment on their own. We used PGY-3s as historical controls for the outcomes survey. Prior to the scheduled appointment, residents completed 4 questionnaires: the Workplace Outcome Suite, the Adverse Childhood Experience questionnaire, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Residents were allowed to “opt out” of their scheduled appointment. Residents who opted out were scheduled for a regular workday.

Each resident saw a licensed therapist with experience treating residents. Visits lasted for approximately 1 hour. Data from the 4 questionnaires were reviewed with residents to aid in assessing and maintaining their self-care (physical, emotional, relationship, and social health) and work-life balance. If other clinically significant issues were identified, such as burnout, depression, anxiety, or trauma, a treatment plan was formulated. If psychiatric care was needed, residents were fast-tracked to see a psychiatrist in the community.

All information obtained, including data from the screening tools, was confidential, and was not shared with program administration. All clinical documentation was kept separate from the institution's electronic health record. If follow-up visits were warranted or requested, they were scheduled, and no vacation or personal/sick day was charged to the resident. There was no personal cost to the resident for the initial or follow-up visits.

Outcomes

To evaluate resident attitudes about the well-being assessment, we used an anonymous survey (provided as online supplemental material). The survey was developed by the authors, who are clinical educators with some survey experience. No pretesting was done. The survey was handed to residents at the close of their semiannual meeting (approximately 1 to 3 months after their well-being assessment visits). Residents were instructed that completing the survey was optional. The survey addressed resident attitudes toward FSAP and perceived barriers to utilization of FSAP services. A section allowed for free-text comments.

The West Virginia University Institutional Review Board deemed the survey and data analysis exempt from review.

Analysis

Mean scoring was performed for each question. A 2-tailed Student's t test was used to compare the means between those who did and did not participate in the well-being assessment. We analyzed data about the residents' perception of FSAP, the likelihood of using FSAP services in the future if they needed assistance, and perceptions about whether the well-being assessment should be continued.

Results

Overall, 38 of 41 PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents (93%) participated, with 3 residents opting out. One hundred percent of interns who participated the first year also participated during PGY-2. Forty-two of 58 residents (72%) in the program completed the survey. Of those completing the survey, 28 (67%) had participated in the well-being assessment program, and 14 (33%) had not, including the PGY-3s and residents who had opted out.

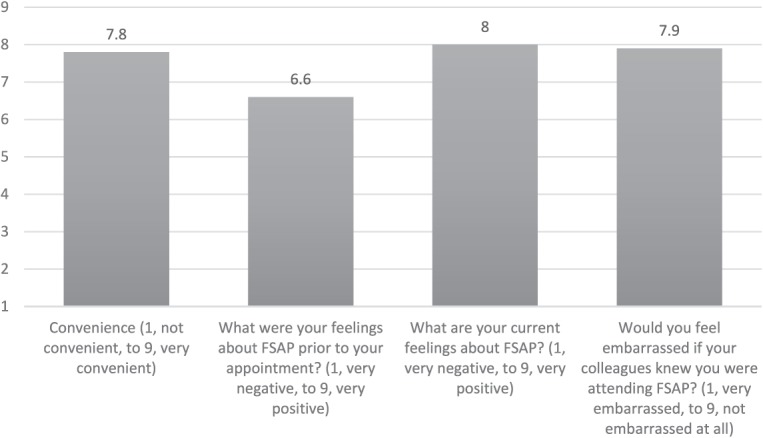

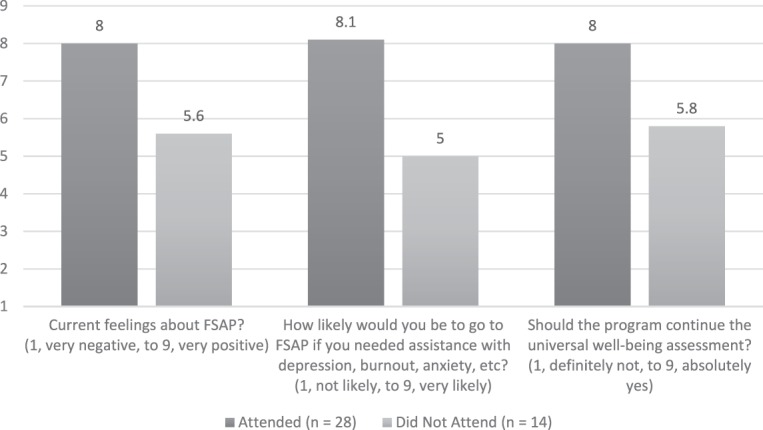

Survey data from residents who attended the well-being assessment are summarized in Figure 1. Residents who participated in the assessment found the process to be convenient, with an average score of 7.8 (1, not convenient, to 9, very convenient). Stigma was assessed by asking whether the residents felt embarrassed if their colleagues knew they were visiting FSAP. The mean rating of those who attended was 7.9 (1, very embarrassed, to 9, not embarrassed at all). Responses from residents who participated in the assessment were compared with those who did not (Figure 2). It showed a more positive mean for residents who attended the assessment (P < .001). Residents who participated in the assessment were also significantly more likely to report they would return to FSAP if they needed assistance with depression, anxiety, and burnout (P < .001). Those who attended were significantly more supportive of the well-being assessment (all P < .001).

Figure 1.

Mean Ratings of Survey Questions of Those Who Attended a Faculty and Staff Assistance Program (FSAP)

Figure 2.

Comparisons of Mean Ratings for Survey Questions of Those Who Attended and Those Who Did Not Attend a Faculty and Staff Assistance Program (FSAP)

Note: All P values < .001.

Discussion

Our universal well-being assessment, in which a wellness interview with a mental health specialist was the default action, resulted in nearly all PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents attending individually scheduled sessions. Those who attended considered the experience generally positive and supported continuation of the program.

The high rate of utilization for this program compared with similar interventions is likely due to the effective mitigation of barriers, as evidenced by the survey results. Confidentiality could be ensured because the FSAP is off-site from our campus and does not use the same health records as our institution. The convenience of having the screening appointment arranged by the program administrator and built in to the residents' schedules addressed concerns about missing work for a service normally only offered during working hours. We also ensured there would be no personal cost to residents for the screening or for subsequent visits. Using an opt-out strategy, and the benefit of a free day from work, likely also contributed to the 93% utilization rate.

We received multiple positive survey comments regarding the well-being assessment project. While some expressed concern about making the process for all residents, the ability to “opt out” prevented residents from feeling forced to attend. Residents who utilized FSAP through the well-being assessment indicated they would be more likely to return to FSAP if needed. This suggests that merely becoming familiar with the available service is the first step to empowering physicians to seek mental health care.

As most institutions have an FSAP or similar program in place, a universal well-being assessment could be an option for other residency programs. Overall staff requirements for scheduling the residents were minimal. The main barrier to other programs implementing a similar project would be funding for licensed therapists to handle the increased volume of residents.

This study has limitations. The survey was developed by the authors and was not tested for evidence of validity, so respondents may have interpreted questions differently than intended. Although residents who took part in the well-being assessment indicated they would be more likely to return to FSAP if they needed assistance with burnout or another mental health issue, to date we have not collected data to corroborate that. The use of 1 cohort of PGY-1 and PGY-2 residents in a single specialty at a single institution limits generalizability to other settings and specialties. Finally, we do not know whether the individualized wellness plan was implemented by individual residents or was effective at improving their well-being.

In the future, when we have sufficient information to ensure confidentiality, we will analyze our data regarding return visits and ongoing care.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that a well-being assessment for internal medicine residents may increase utilization of FSAP services and may reduce common barriers, such as lack of convenience and perceived stigma.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the faculty and staff assistance program survey.

Funding: The authors report no external funding for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Results from this study were presented as a workshop on resident wellness at the Academic Internal Medicine Week, Baltimore, Maryland, March 19–22, 2017.

What was known and gap

Resident physician utilization of well-being resources remains low despite efforts to enhance access.

What is new

A universal well-being screening assessment for all postgraduate year 1 and 2 residents in an internal medicine program.

Limitations

Single site, single specialty study may limit generalizability; survey instrument lacks validity evidence.

Bottom line

A universal well-being assessment for all residents can be readily implemented and may reduce barriers to resident use of counseling resources.

References

- 1. . Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. . Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015; 314 22: 2373– 2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. . Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. . Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004; 161 12: 2295– 2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. . Gold KJ, Sen A, Schwenk TL. . Details on suicide among US physicians: data from the national violent death reporting system. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013; 35 1: 45– 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. . Guille C, Speller H, Laff R, et al. . Utilization and barriers to mental health services among depressed medical interns: a prospective multisite study. J Grad Med Educ. 2010; 2 2: 210– 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. . Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. . “If you build it, they will come”: attitudes of medical residents and fellows about seeking services in a resident wellness program. J Grad Med Educ. 2013; 5 3: 486– 492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. . Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, et al. . Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: a decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016; 8 5: 747– 753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.