Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of plasma membrane receptors. Emerging evidence demonstrates that signaling through GPCRs affects numerous aspects of cancer biology such as vascular remolding, invasion, and migration. Therefore, development of GPCR-targeted drugs could provide a new therapeutic strategy to treating a variety of cancers. G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) modulate GPCR signaling by interacting with the ligand-activated GPCR and phosphorylating its intracellular domain. This phosphorylation initiates receptor desensitization and internalization, which inhibits downstream signaling pathways related to cancer progression. GRKs can also regulate non-GPCR substrates, resulting in the modulation of a different set of pathophysiological pathways. In this review, we will discuss the role of GRKs in modulating cell signaling and cancer progression, as well as the therapeutic potential of targeting GRKs.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK), Cancer, Cell signaling

Introduction

More than 700 genes have been identified as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), which form the largest protein superfamily in the human genome 1. GPCRs play key roles in mediating a wide variety of physiological events, from hormonal responses to sensory modulation (vision, olfaction, and taste) 2, 3. GPCR-targeting drugs are used to treat many diseases. Over 40% of all FDA approved drugs are aimed at targeting GPCRs or their related pathways 4. GPCRs are now being used as early diagnosis biomarkers for cancer, as they play integral roles in regulating and activating cancer-associated signaling pathways 5, 6. Though GPCRs represent a growing share of all new anticancer therapies, “druggable” GPCRs represent only a small subset of receptors from this superfamily 5, 7. This is mainly due to drug resistance, as studies that have used short- and long-term exposure to GPCR-targeting drugs have observed receptor desensitization 5, 8, 9. Therefore, the pharmacological potential for GPCRs and their downstream regulators requires further investigation in order to further develop therapies that can efficiently target cell signaling pathways in cancer 6.

GPCR signaling generally results in the transmission of amplified signals throughout the cell, and hyperactivation of these receptors may result in loss of normal cell physiological properties. There are several mechanisms including GTP hydrolysis, second messenger related protein kinases (e.g., PKA and PKC), G-protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), and arrestins that prevent hyperactivation of GPCR signaling. However, the most important mechanism of terminating GPCR hyperactivation is GRK-mediated phosphorylation. Upon ligand-dependent receptor activation, GRK phosphorylates its target GPCR to prevent excessive cellular signaling. The details of this GPCR termination mechanism will be discussed in our review. Because GRKs act as negative regulators of GPCR activity, it has been suggested that they may play a role in cancer progression by regulating cell proliferation, migration, apoptosis, invasion, and tumor vascularization in a cell type-dependent manner 10-14. Therefore, a complete understanding of their role in GPCR signaling is of high clinical importance. In this article, we will review current research linking GRKs to various aspects of cancer biology and discuss the therapeutic potential of targeting GRKs.

Role of GRKs in GPCR signaling pathway

GPCR signaling pathway

GPCRs serve as the interface between intracellular and extracellular environments. Receptors of this family are characterized by seven highly hydrophobic transmembrane helix structures. Stimuli, such as photons, small chemicals, ions, or protein ligands induce conformational changes in GPCR, which translates into cell signaling responses by activating coupled trimeric G protein complexes 15. Based on sequence and structural similarity, GPCRs are classified into five subfamilies, namely rhodopsin, secretin, glutamate, adhesion, and frizzled 1. The core structure of each GPCR can be divided into three domains: the extracellular region (ECR), which includes the N-terminus and three extracellular loops, the transmembrane region (TM), which includes seven α-helices, and the intracellular region (ICR) that contains three intracellular loops, an intracellular amphipathic helix, and theC-terminus 16. Generally, the functional role of the ECR is to initiate binding of specific ligands. The TM region forms the receptor core structure, which is important for transducing extracellular stimulus through conformational changes. The TM region may also be involved in ligand binding in the majority of GPCRs. The ICR interacts with coupled G proteins, which are activated through conformational changes, and transduce downstream intracellular signaling 16.

Upon induction of conformational changes, GPCRs mediate signaling through G protein heterotrimers (Gα, β, and γ subunits) 17. These G proteins help transduce downstream signaling amplification based on the different functions of each Gα subunit isoform. Heterotrimeric G proteins transduce signals by exchanging GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit in response to ligand dependent activation of the GPCR. The Gα-GTP subunit can then separate from the Gαβγ heterocomplex and interact with its downstream signaling effectors. Because different GPCRs interact with a diverse array of intracellular coupled Gα protein isoforms, they can modulate a variety of downstream signaling pathways, and cause unique physiological responses when activated by different stimuli (Figure 1) 18.

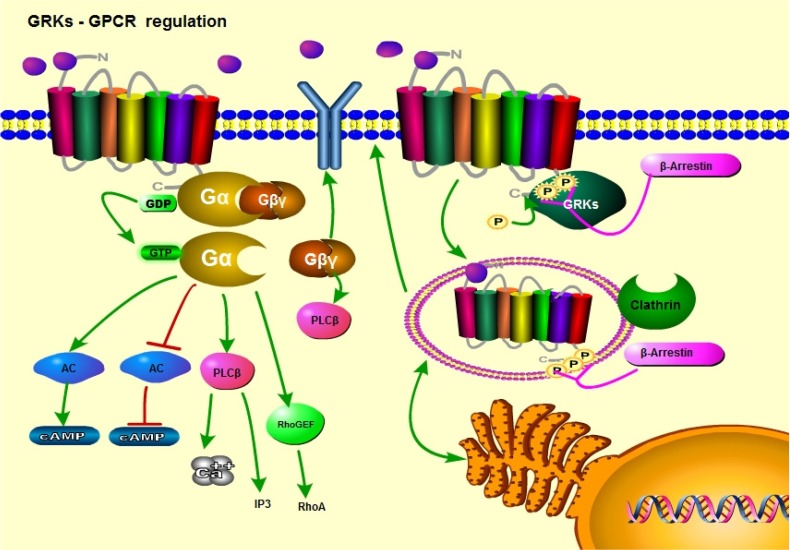

Figure 1.

GPCR/GRK cell signaling; a general view. Upon ligand binding, GPCRs activate downstream signaling pathways through their coupled Gα subunits. In response to GPCR conformational changes, G proteins activate downstream targets by converting GDP to GTP. GRKs phosphorylate the intracellular regions of GPCRs. This results in receptor desensitization and arrestin recruitment. Arrestins initiate receptor endocytosis, followed by receptor recycling or degradation.

GRK family

The GRK family is comprised of seven serine/threonine kinases. The main function of these proteins is to inhibit activated GPCRs. Mammalian GRKs are classified into three subgroups based on sequence similarity (Figure 2): the rhodopsin kinases (GRK1 [rhodopsin kinase] and GRK7 [cone opsin kinase], the β-ARK subgroup (GRK2 and GRK3), and the GRK4 subgroup (GRK4, GRK5, and GRK6). In humans, there are four GRK4 splice variants (GRK4-α, GRK4-β, GRK4-γ, and GRK4-δ), and three GRK6 splice variants (GRK6A, GRK6B, and GRK6C) 19, 20.

Figure 2.

Molecular characteristics of the GRK protein family. All GRKs (60-80KDa) possess a similar molecular structure with an α-N-terminal domain followed by an N-terminal Regulator of G protein Signaling domain (RGS/N), which is important for receptor recognition and intracellular membrane anchoring 153, 154. The protein kinase catalytic domain with a short AGC protein kinase domain is responsible for GRKs catalysis. The C-terminus has more motif variants than the RGS/C domain, which is critical for receptor recognition 14. Unlike other isoforms, the GRK2 subfamily (GRK2 and GRK3) has a pleckstrin homology domain (PH), which is important for terminating Gβγ complex-related downstream signaling. The C-terminus length varies among all GRK subtypes (~105 to 230 AAs).

All mammalian GRKs possess a similar protein structure, with a catalytic domain (~270 amino acids), an N-terminal domain (~185 amino acids), and a variable-length C-terminal domain (~105-230 amino acids). The N-terminal domain contains two conserved motifs for ligand binding and plasma membrane insertion 21, 22. A single regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) domain (~120 amino acids) is located within each of the N- and C-terminal domains, and both RGS domains contain a kinase catalytic domain (KD). The RGS domains regulate GPCR function via phosphorylation 23-25. Phosphorylation occurs in response to ligand binding to GPCR. GRK-induced phosphorylation of cytoplasmic serine and threonine residues of GPCR triggers conformational changes in the receptor, revealing high affinity helical binding domains for β-arrestins. As a result, β-arrestin binds to the GPCR and inhibits downstream signaling 26. Because GRKs also belong to protein kinase A, G, and C families (AGC), all GRKs share a conserved AGC sequence, which is important for kinase activity 27. Unlike other GRKs, GRK2 and GRK3 have a pleckstrin homology domain (PH), which is critical for serine/throenine phosphorylation site recognition and termination of Gβγ-induced signaling 28, 29. In addition, the Gβγ binding site of GRK2 is located in the N-terminal domain, which is involved in GRK2 cell surface localization and termination of G-βγ downstream signaling 30. Furthermore, GRK4 has a phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-biphosphate (PIP2) motif in its N-terminal that can increase its catalytic kinase activity 31.

GRK4 is predominately expressed in the brain, kidney, testis, and human granulosa cells 32-35. GRK1 and GRK7 are expressed mainly in retinal cells, where they mediate photo-transduction by phosphorylating rhodopsin receptors 36. All other GRKs are expressed ubiquitously throughout the body and regulate the functions of a variety of GPCRs 37.

There are many more types of GPCRs than GRKs, with each GRK interacting with and phosphorylating multiple GPCRs 13. However, several groups have found that a subset of GRKs show substrate specificity with a select few GPCRs, despite the structural similarity of their domains. Therefore, the physiological roles of each GRK isoform may vary significantly 38. In agreement, GRKs can find other regions of their targeted GPCR to phosphorylate even when the domain is mutated 39. The N-terminus of each GRK is highly conserved and critical for GPCR identification. However, how GRKs recognize GPCR conformational changes is still unknown, making its role during GPCR activation unclear 40.

Termination of GPCR signaling

The major function of GRKs is to mediate signaling termination through phosphorylation of activated GPCRs. The activated GPCR is directly regulated by two major mechanisms involving both GRKs and arrestins, where arrestins are recruited to the GPCR upon phosphorylation by GRKs. These two interacting regulatory proteins terminate GPCR intracellular signal transduction, and control G protein subunit coupling.

The mechanism of GPCR inhibition involves GRK phosphorylation of the intracellular regions of the target GPCR. Arrestins then bind to the phosphorylated GPCR domain to inhibit further G protein activation. This process leads to GPCR desensitization, internalization, and recycling or degradation, which require the recruitment of other proteins such as AP-2 and clathrin. To phosphorylate a ligand-bound GPCR, the GRK must be located at (or translocated to) the plasma membrane, where it forms a complex with the receptor. GRK1, GRK4, GRK5, GRK6, and GRK7 are normally found on the plasma membrane, where they bind and phosphorylate their target receptors. However, GRK2 and GRK3 require further steps in order to localize to the plasma membrane. These two kinases are mainly localized in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum. Only upon GPCR activation do they recognize detached Gβγ subunits and undergo translocation to the plasma membrane to desensitize GPCRs 41. Once a ligand binds to a GPCR, GRKs sense the intracellular conformational changes as it separates from coupled G protein subunits. They can then phosphorylate the C-terminus of the target GPCR 42. Phosphorylation will then induce additional GPCR conformational changes and increase its affinity for arrestins. The binding of arrestins prevents further coupling of G protein subunits and inhibits second messenger signal transduction 43. Furthermore, GRKs also attenuate GPCR signal transduction by controlling the responsiveness of GPCRs to their ligands. This GPCR desensitization allows the cell to distinguish between different types of ligands, such as chemokines, and define the intensity of the cellular response 44. Previous studies have shown that GRK specificity for a particular GPCR is determined largely based on the ligand bound to the GPCR 45.

GPCR desensitization

GPCRs amplify signals in response to ligand binding in a dose-dependent manner. Stimulated receptors become less sensitive due to the amount of time they remain in their active form, a phenomenon known as receptor desensitization 24, 46, 47.

In 1983, Sitaramayya et al., demonstrated that GRK1-mediated rhodopsin phosphorylation correlated with cGMP phosphodiesterase activity, and suggested that GRK1 was involved in GPCR desensitization 48. Thereafter, the importance of pleckstrin homology/Gβγ-binding domain in the recruitment of GRK5 during GPCR desensitization was shown in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, it was found that in the absence of phosphorylation by GRKs, GPCR receptor desensitization was greatly minimized 49. Overexpression of GRK2 and β-arrestin in COS-7 cells resulted in GRK2-mediated phosphorylation of the β-adrenergic receptor, and subsequent recruitment of β-arrestins 50. Several in vivo studies have identified co-localization of GRK3 and β-arrestin-2 in olfactory neuroepithelium in conjunction with dendritic knobs and cilia, and that GRK2 and β-arrestin-1 are not expressed in these tissues. In response to odorants such as citralva, GRK3-mediated GPCR desensitization was β-arrestin-2-dependent 51. With regards to GRK4, no receptor substrate had been identified prior to 2000, when Sallese et al., successfully demonstrated that metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGlu1) signaling could be desensitized by GRK4 in an agonist-dependent manner in HEK293 cells 52. GRK7 was the last GRK family member identified, and was co-expressed with GRK1 in cone photoreceptor cells 53. In a zebrafish model, GRK7A deficiency affected cone bleaching adaptation and spontaneous decay, which highlighted the role of GRK7 in GPCR desensitization in scotopic vision 54.

GPCR internalization and degradation

Internalization is an important mechanism used by cells to regulate GPCR activity and to allow recovery post desensitization. Internalization involves the endocytosis of activated receptors from the plasma membrane, a process that requires GRK activity. The presence of GRKs and their interaction with clathrin in endocytosed vesicles highlights the role they play during receptor internalization 55. GRKs interact with clathrin through a clathrin-box structure located within the C-terminus normally used to form clathrin-coated pits, and the removal of this domain led to loss of GPCR internalization 56. For example, silencing of clathrin heavy chain protein inhibited β-adrenoceptor internalization and phosphorylation, suggesting clathrin may also regulate GRK activity 43, 57.

Goodman et al. previously demonstrated that β-arrestin subunits 1 and 2 were important in facilitating GPCR internalization 58. The association of GRKs and arrestins with the C-terminus of various GPCRs led to shuttling of the internalized complex to lysosomes. Interestingly, the binding of β-arrestin to GPCRs was dependent on GRK phosphorylation of the target receptor. In cases of spontaneous β-arrestin-independent internalization, the receptor may also be recycled back to the plasma membrane 59.

In the case of β-adrenoceptor, upon ligand binding, receptor internalization occurred upon recruitment of phosphatidylinositol-4-5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma (PI3Kγ) to the cell surface 60. Structural studies of the PI3Kγ protein suggested its PIK-domain interacted directly with GRK2 61. In addition, GRK2 mediated desensitization of G protein-coupled receptor 54 (GPR54) through inositol-(1,4,5)-triphosphate (IP3) formation in response to increasing concentrations of Kisspeptin-10 62. Co-transfection of melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) and GRK2 or GRK6 in heterologous cells has been shown to impair agonist-dependent cAMP signaling. This indicated that desensitization of MC1R occurred through GRK2 and GRK6 63.

One of the key roles of GRKs is to regulate the number of GPCRs at the plasma membrane through receptor internalization, which can prevent hyperactivation of the target receptor. Internalized receptors are then degraded by endocytic trafficking to lysosomes. This process can occur either rapidly or over a longer period of time. The internalization and degradation of the β2-adrenergic receptor occurs within seconds to minutes upon agonist binding, and can be reversed within minutes after removal of the agonist without new receptor synthesis, a process that is regulated by GRK2. Normally, a rapid reduction of cell surface receptors only temporarily desensitizes the receptor. However, slower regulation of receptor numbers requires receptor endocytosis in combination with synthesis of new receptors, which also involves ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation and GRK3 and GRK6 64, 65.

GPCR biased signaling with GRK

The discovery of the concept of "biased signaling of GPCR" has revised the classical understanding of GPCR signaling. It is believed that activated GPCR conformation will promote either G-couple proteins or β-arrestin signaling or both, with a ligand known as "G-protein-biased agonist", "β-arrestin-biased agonist", or "balanced agonist". The current molecular mechanism of this phenomenon has not been fully revealed yet. The prevailing hypothesis is that GPCR may have a special activated conformational state in response to each ligand leading to different exclusive downstream modulator(s). β-arrestin does not only serve as the terminator of GPCR signaling, but also acts as a signaling protein, in which the "β-arrestin-biased signaling" always requires phosphorylated GPCR. Therefore, GRKs are suggested to be critical for therapeutic strategies of β-arrestin-biased signaling, because GRKs are able to promote high-affinity binding of β-arrestin to GPCRs. Interestingly, β-arrestin may have distinct responses to different GRK subtype phosphorylation of the same GPCR. Kelly et al. used β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) as an example to demonstrate that different GRK subtypes phosphorylate distinct intracellular sites 38. After over-expression or silencing of GRK2 or GRK6 through transfection in HEK293 cells, and treatment with either unbiased full agonist (isoproterenol) or β-arrestin-biased agonist (carvedilol), the author used specific antibodies against 13 phosphorylation sites on the β2AR to analyze phosphorylated sites by each GRK subtype. The result revealed six (Thr360, Ser364, Ser396, Ser401, Ser407, and Ser411) and two (Ser355 and Ser356) phosphorylation sites for GRK2 and GRK6, respectively. In addition, GRK2 suppressed phosphorylation of the two sites phosphorylated by GRK6. Moreover, GRK6, but not GRK2, is essential for β-arrestin-dependent ERK1/2 activation. Additional evidence for β2AR phosphorylation using PKA assay screening of Ser355 and Ser356 mutants was given by Xiaofang et al. 66. Their data supported the hypothesis that GRK subtypes might have preferential phosphorylation and trigger unique conformational changes in GPCR. The different phosphorylation pattern therefore directly affects β-arrestin-dependent functions. Other receptors such as kappa opioid receptor, mu-opioid receptor, angiotensin II receptor type 1A, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, and vasopressin type 2 receptor were also reported to exhibit similar properties and showed a contradictory role between GRK2/GRK3 and GRK5/GRK6 in β-arrestin-mediated signaling 67-72. However, there are limited studies on the physiological and pharmacological functions of GRK in GPCR-biased signaling. More importantly, because β-arrestin-biased signaling is involved in the cancer-related signaling pathway, the role of GRK in β-arrestin-biased signaling in cancer is worthy of attention.

Role of GRKs in non-GPCR signaling pathway

GRKs play significant roles in non-GPCR-mediated signal transduction by phosphorylating proteins such as receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK). Previous studies have hypothesized a link between GRKs and RTK signaling that not only reveals the diverse role of GRKs in controlling intracellular signaling, but also highlights the potential benefit of targeting GRKs in cancer. In this section, we will discuss several examples of GRK regulation of non-GPCR signaling pathways.

Early evidence for GRKs as modulators of RTK signaling was based on the observation that ligand activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promoted GRK2 translocation to the plasma membrane to initiate EGFR internalization. EGFR activation of ERK/MAPK via phosphorylation was enhanced in HEK293 cells in response to overexpression of GRK2. These results indicate GRK2 regulated not only EGFR internalization but also its ability to transduce signals 73. Furthermore, EGF stimulation induced the formation of a GRK2/EGFR complex in a Gβγ-dependent manner 74, and pretreatment with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor, AG 1478, reversed this effect 74. Other targets of GRK2 include the retinal photo-receptor type 6 cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) phosphodiesterase (PDEγ), which is found in the internal membranes of retinal photoreceptors, where it reduces cGMP in rod and cone outer segments in response to light 75. Wan et al. demonstrated that GRK2 targeted PDEγ in a complex with c-Src whereby threonine 62 of the PDEγ was phosphorylated 76. This is consistent with earlier reports that Src mediates GRK2 phosphorylation of other plasma membrane proteins 77. In addition, GRKs mediate the cross talk between RTK and GPCR signaling pathways, such as that which exists between the δ-opioid receptor (DOR), the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), and EGFR 78.

Reduced platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) signaling is also found to be associated with GRK2 expression. By modulating the levels of GRK2 expression, Freedman et al. showed that phosphorylation of PDGFR could be altered by GRK2 79. It was subsequently found that GRK2 enhanced the ubiquitination of PDGFR leading to its desensitization. In smooth muscle cells, overexpression of full-length GRK2 significantly decreased PDGFR activity in a Gβγ-independent manner, but this effect was abrogated in cells expressing a truncated version of GRK2 consisting of only its pleckstrin homology/Gβγ-binding domains 80. However, in the case of GRK5 that lacks pleckstrin homology domain, PDGFR could still be phosphorylated 81. Moreover, knocking out GRK2 in HEK293 cells strongly enhanced downstream PDGFR signaling, resulting in increased AKT activation 82. Therefore, the catalytic activity of PDGFR is dependent on the inhibitory activities of GRK2 and GRK5.

Interestingly, an opposite effect was found with regards to the modulation of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) signaling by GRK2, where reduced GRK2 levels inhibited IGF1-R activation. Silencing of GRK2 also enhanced the expression of cyclins and IGF1-R in human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells 83, and silencing GRK5 and GRK6 also impaired IGF1-R signaling. However, silencing GRK3 had no effect on the status of IGFR-1 84. In this study, GRK2 and GRK6 were found to counteract each other with regards to IGF-1R activation and ERK phosphorylation. It was then suggested that IGFR-1 interacts with both GRK2 and GRK6 to promote β-arrestin recruitment 84.

Previous studies have illustrated an interaction between vascular endothelial cell growth factor receptor (VEGFR) and GRK in the cardiovascular system and during tumor angiogenesis. Here, GRK5 was shown to regulate VEGF signaling and activation of its downstream effectors (AKT, ERK1/2, and GSK-3) in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs). However, Sandeep et al. demonstrated that GRK6 depletion enhanced tumorigenesis and metastasis using a GRK6 knock-out mouse model of Lewis lung cancer 85.

There have also been reports of interactions of GRKs with a wide range of other membrane or intracellular proteins, such as nucleophosmin, cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), HSP90, HSP70 interacting protein (Hip), similar mothers against decapentaplegic homolog (SMAD), Rho, synucleins, phosducin, P38, histone deacetylase 5(HDAC5), activin receptor-like kinase 1/5 (ALK1/5), glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4), mammalian STE20-like kinase 2 (MST2), never in mitosis gene related kinase 2A (NEK2A), tubulin, ezrin, and many other functional proteins 86-102 (summarized in Figure 3). As an example, GRK2 does not directly phosphorylate sphingosine-1 phosphate receptor (S1PR), but via G-protein-coupled receptor kinase interacting protein-1 (GIT1) to activate the MEK/MAPK/ERK cascade to induce epithelial cell migration 103. In summary, GRKs play diverse roles in regulating the activity of GPCRs, RTKs, and other receptors to control cell behaviors and maintain homeostasis.

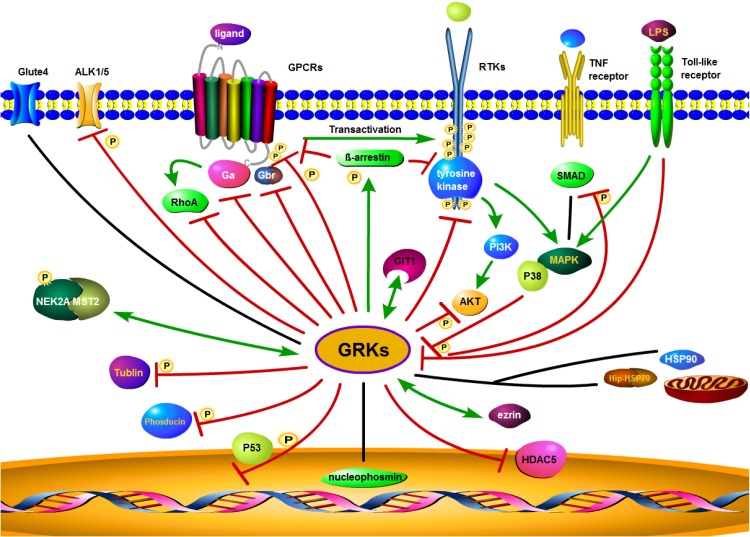

Figure 3.

Proposed GRK interaction networks. GRK plays a diverse role in intracellular signaling. GRKs promote β-arrestin binding to both GPCRs and RTKs. Through their interaction with clathrin coated plasma membrane pits, GRKs mediate receptor internalization, followed by receptor degradation or recycling. GRKs also interact with other intracellular or membrane proteins and modulate interrelated signaling through phosphorylation. Red lines indicate an inhibitory effect of GRKs, while green lines indicate a stimulatory effect. The black lines represent no inhibitory or stimulatory activity.

The role of GRK in GPCR transactivation

In the past decade, GPCR transactivation has further broadened this signaling network, with the two known patterns being from GPCRs to receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) and receptor serine/threonine kinases (RS/TK). Two mechanisms, ligand-dependent and ligand-independent, are generally accepted for GPCR-RTK transactivation. Membrane-bound matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) play predominant roles in ligand-dependent receptor transactivation. Following GPCR activation, MMP levels increase to enhance the release of membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor (HB-EGF)104. HB-EGF further activates EGFR and hence triggers the metastatic and invasive behaviors of cancers. The ligand-independent pathway is based on GPCR activation of Src family proteins, which phosphorylate the intracellular tyrosine residues of RTK to activate the downstream signaling pathway. Examples of GPCR-RTK transactivation in cancers are well summarized in articles written by Almendro et al. 105.

Regarding RS/TK transactivation by GPCR, recent accumulating evidence establishes a GPCR-ROCK-Integrin-TGFBR (ALK5) pathway. Burch et al. properly demonstrated that thrombin activated PAR-1 to transactivate TGF-beta receptor by integrin binding to LLC with conformational alternation that led to TGF-ligand initiation of ALK5 downstream pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells 106. Also this report supported an early research model on integrin-LLC-ALK 107.

As discussed above, current studies of GRKs involve GPCR-dependent and RTK-dependent mechanisms. As recently evidenced by Kamato et al. using RNA-sequencing in vascular smooth muscle cells, over 50% GPCR-activated gene expression was accounted for by RTKs and RS/TKs transactivation 108. Thus, the role of GRK in GPCR-RTK or GPCR-RS/TK transactivation regulation is becoming more apparent and important in cancer research (Figure 4).

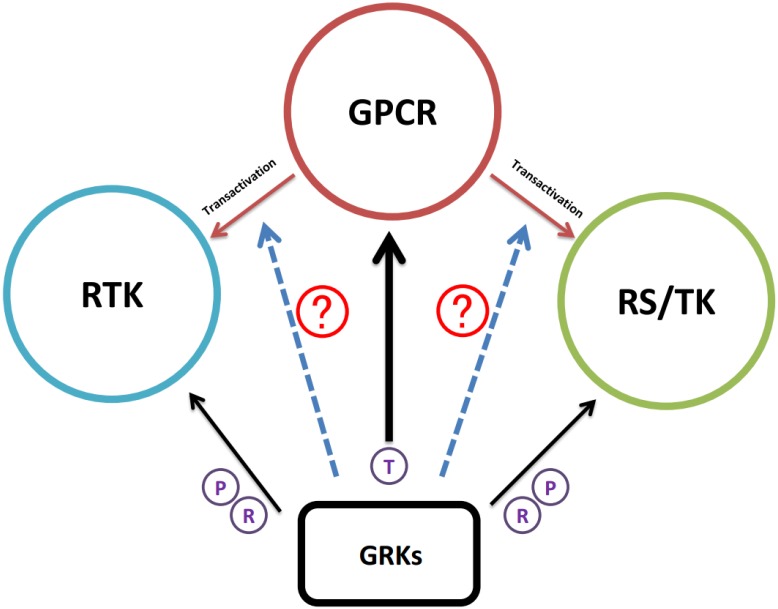

Figure 4.

Schematic illustration of GRK regulation research progress. Accumulating evidence suggested that GRKs have the regulatory function in GPCR, RTK, and RS/TK signaling pathways. As GPCR induced transactivation of RTK or RS/TK that further broadened the GPCR network map, the next research area will be certainly turning into the potential functions of GRKs during the transactivation process. Black arrow; studies have confirmed interaction between GRKs and the target substrate. Dotted blue arrow; potential function of GRK in the transactivation of RTK or RS/TK. T in circle; signaling termination. P in circle; receptor phosphorylation. R in circle; regulation of receptor activities after interaction.

The role of GRKs in cancer pathology

Because GPCR signaling is an important contributor to tumor growth and metastasis, discerning how GRKs regulate GPCR activity in cancer cells may greatly improve our understanding of tumorigenesis and oncogenesis, and help develop novel anticancer therapies. In the following section, we discuss the role of GRKs in cancer progression (an overview is summarized in Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of previous studies investigating GRKs in cancer.

| GRK subtype | Type of cancer | Interacting protein | Function | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRK2 | thyroidcarcinoma | TSHR | ↓proliferation through rapid desensitization | 113 |

| hepatocellularcarcinoma cell | IGF1-R | ↓proliferation and migration | 12 | |

| human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) | IGF1-R | ↓cell cycle progression | 83 | |

| pancreatic cancer | N/A | --T-stage and poor survival rate | 115 | |

| breast carcinosarcoma | NGFR | ↓bone cancer pain | 116 | |

| Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infected tumor cell | CXCR2 | ↓migration and invasion | 117 | |

| basal breast cancerwith Her-2 amplification /infiltrating ductal carcinoma | Her-2/ER-α | ↑promoting mitogenic, anti-apoptotic activities -survival and progression | 155 | |

| luminal and basal breast cancer | HDAC6/Pin1 | ↑sensitiveness of breast cancer cells to traditional chemotherapeutic treatment | 119 | |

| breast cancer | CXCR4 | ↓metastasis | 120 | |

| human gastric carcinoma cell line (MKN-45) | H2 receptor | --poor differentiation | 121 | |

| human breast cancer | N/A | ↑tumor growth↓angiogenesis | 98, 122 | |

| GRK2/5/6 | gastric cancer (SSTW-2) | recoverin | --tumor progression, metastasis | 11 |

| GRK2/6 | melanoma | melanocortin 1 receptor | --determinant for skin cancer | 63 |

| GRK3 | breast cancers (MDA-MB-231,MDA-MB-468) | CXCR4 | ↓metastasis ↓migration | 123 |

| prostate cancer(PC3) | N/A | ↑metastasis, tumor progression, angiogenesis | 124 | |

| retinoblastoma(Y-79) | CRF1 receptor | ↑stress adaptation | 125 | |

| oral squamouscarcinoma | β2-adrenergic receptor | --tumor malignancy and invasion | 126 | |

| GRK4 | ovarian malignant granulosa cell tumor | FSHR | --benign and malignant transformation in tumor development | 35 |

| GRK5 | glioblastoma | N/A | --proliferation rate and WHO Grade | 130 |

| thyroid carcinoma | TSHR | ↓proliferation through slow desensitization | 113 | |

| prostate cancer(PC3) | ↓proliferation, cell cycle | 131 | ||

| prostate cancer (PC3, DU145, LNCaP ) | Moesin | ↓migration, invasion ↑cell adhesion |

132 | |

| prostate cancer | N/A | ↑tumor growth, invasion and metastasis | 133 | |

| osteosarcoma (U2OS,Saos-2) | P53 | ↓cell apoptosis | 90 | |

| GRK6 | hepatocellular carcinoma | N/A | --proliferation maker in early diagnosis | 134 |

| hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma(FaDu) | Methylation of GRK6 | --cancer progression ↓invasion |

135 | |

| medulloblastoma | CXCR4/ EGFR/PDGFR-Src | ↑migration | 136 | |

| lung cancer | CXCR2 | ↓cancer development | 85 | |

| GRK1/7 | recoverin | --cancer-associated retinopathy | 112 |

N/A= not provided by research ↑=increase or promoting related mechanism↓=decrease or diminish related mechanism --=has association with.

GRK1 and GRK7

Because GRK1 and GRK7 are almost exclusively expressed in retinal tissue (cone and rod cells) and phosphorylate opsin GPCRs during visual acquisition, only a handful of cancers have been implicated in dysfunctional GRK1/7 activity. Several groups have shown that GRK1 and GRK7 may be involved in embryogenesis, but also indirectly interact with proteins such as Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor (RohGDI) and PDEγ, both of which have been found to be aberrantly regulated in cancer 109, 110. Furthermore, reductions in GRK1 activity due to a mutation or deletion causing nonfunctional protein, have been shown to contribute to the onset of Oguchi disease (stationary night blindness Oguchi type-2) 111. A direct link between reduced GRK1/7 activity and cancer progression has not yet been confirmed. However, GRK1/7 may play a role in cancer-associated retinopathy through its interaction with recoverin (a calcium binding protein) in patients with lung cancer 112.

GRK2

The role of GRK2 in cancer has been well-characterized. High levels of GRK2 expression are found in differentiated thyroid carcinoma, whereas GRK5 levels are significantly deceased when compared to normal thyroid tissue. The levels of GRK2 protein are correlated with its activity, as it rapidly desensitizes thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor (TSHR), whereas GRK5 inhibits desensitization of this receptor. In thyroid carcinoma, activation of TSHR increased cancer cell proliferation 113. In human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells, GRK2 negatively regulates Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1-R) signaling. In GRK2 knockdown cells, reduced GRK2 levels enhanced cyclin and IGF1-R expression. These results highlight the role of GRK2 in suppressing cell cycle progression 83. Another study using hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HCCs) demonstrated that GRK2 inhibits IGF1 signaling, thereby regulating proliferation and migration 12. It is generally believed that IGF-1 induces the expression of early growth response protein 1 (EGR1) through reactive oxygen species (ROS)-dependent activation of ERK1/2/JNK and PI3-K/PKB 114. Modulating the levels of GRK2 expression in HCCs demonstrated that GRK2 regulated EGR1 expression after IGF1 treatment. Altogether, these studies reveal the therapeutic potential of GRK2 by inhibiting IGF1-mediated responses 12, 83, 84. Moreover, in clinical studies, high GRK2 expression correlated with a high tumor (T) stage and poor survival rates of patients with pancreatic cancer. However, these levels could not be considered as an independent prognostic marker 115.

Yao et al. used a rat osteosarcoma model to evaluate the association between GRK2 and cancer-related pain levels in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Implanted breast carcinosarcoma cells in the tibia resulted in increased expression of GRK2. Nerve growth factor (NGF), together with GRK2, promoted the phosphorylation of opioid receptors, and an increase in pain. In addition, anti-NGF therapies mediated the effects of GRK2 and arrestins to significantly relieve cancer bone pain 116.

GRK2 is also involved in miRNA mediated pathways. MiR-K3, a Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) encoding miRNA, facilitates endothelial cell migration and invasion. Interestingly, overexpression of GRK2 in KSHV infected tumor cells reversed this miR-K3-dependent induction. In addition, miR-K3 directly up-regulated GRK2 expression. Moreover, downregulation of miR-K3 by GRK2 inhibited the migration and invasion of KSHV infected HUVEC cells. These results suggest that GRK2 plays a role in suppressing KSHV-associated tumor progression 117.

GRK2 has also been implicated in breast cancer progression. GRK2 levels are elevated in precursor lesions of mammary glands in mouse mammary tumor virus with Her-2 amplification (MMTV-HER2) mice. The expression of GRK2 is also dependent on estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) signaling in human breast cancer cell lines. Moreover, increased GRK2 levels may contribute to cellular transformation by promoting mitogenic and anti-apoptotic activities during tumor development. Data obtained from breast cancer patients showed that GRK2 levels were significantly increased in infiltrating ductal carcinomas. This strongly suggests that a relationship exists between GRK2 activity and breast cancer progression 118. Interestingly, a recent study demonstrated that up-regulation of GRK2 was associated with increased histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) expression. GRK2 increased the growth of both luminal and basal breast cancer cells in an HDAC6- and peptidylprolyl-cis/trans-isomerase (Pin1)-dependent manner, and inhibition of GRK2 increased the sensitivity of these cells to commonly used chemotherapeutic compounds. Therefore, the GRK2-HDAC6-Pin1 axis may be a potential therapeutic target for combination therapy 119. Finally, GRK2 was found to be a negative regulator of CXCR4 (C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4), a chemokine receptor that mediates metastasis and is typically used as an indicator of patient prognosis 120.

GRK2 also plays a role in gastric cancer progression, as studies using human gastric carcinoma MKN-45 cells have shown that GRK2 mediated the homologous desensitization of H2 receptors in poorly differentiated cancers 121. Desensitization of H2 receptors by histamine was inhibited in response to treatment with a GRK2, but not GRK6, antisense phosphorothioateoligo-DNA (PON). This indicates that GRK2 and GRK6 play significantly different roles in modulating H2 receptor pathways in MKN-45 cells.

With regards to the role of GRK2 in skin cancer, low expression of GRK2 in melanoma cells could enhance cAMP production in response to MC1R agonists. MC1R has been shown to regulate pigmentation and differentiation of epidermal melanocytes and contributed to melanoma progression. This effect was reversed by overexpressing GRK2 and GRK6 63. Thus, GRK2 and GRK6 may regulate the development of skin cancer by modulating MC1R signaling.

A systematic study by Penela et al. described the regulatory role of GRK2 in tumor vessel formation, as it modulated the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells, and promoted hypoxia and macrophage infiltration during tumor angiogenesis 122. Rivas et al. further suggested that GRK2 is involved in tumor vessel formation and acts as a regulator of angiogenesis through neovascularization in breast cancer. Using hemizygous GRK2 (GRK2+/-) and endothelium-specific GRK2 knockout mice, it was also shown that reduced GRK2 levels enhanced tumor growth and promoted new blood vessel formation 98.

GRK3

Fitzhugh et al. firstly showed a role for GRK3 in breast cancer progression as knockdown of this gene in MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 cells inhibited CXCL12-mediated chemotaxis, suggesting that GRK3 regulates CXCR4 activation of CXCL12 123. In vivo, stable knockdown of GKR3 resulted in a high metastatic rate of xenograft breast cancer. Interestingly, according to the study by Billard et al., GRK3 regulated CXCR4 signaling in triple negative and other molecular subtypes of breast cancer 13. In these studies, GRK3 protein and mRNA expression levels were sensitive to chemokine-mediated migration. This observation was supported by other studies that used extracted data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database. Here, the authors demonstrated that the ratio between GRK3 and CXCR4 may be a key factor in controlling tumor migration and metastasis. Although these authors did not perform in vivo experiments to confirm their findings, they clearly showed that breast cancer metastasis was inhibited by GRK3 through regulation of CXCR4 signaling.

Prostate cancer has also been used as a model to discern the role of GRK3 in metastasis, tumorigenesis, and angiogenesis. Li et al. found significantly increased migration of endothelial cells in response to elevated expression of GRK3. One group implanted GRK3 knockdown cells into the prostates of SCID mice, and observed enhanced proliferation and metastasis of primary tumors. Microvessel density was modulated by overexpression of GRK3 in primary tumor cells, indicating GRK3 mediated angiogenesis. In agreement, the expression levels of GRK3 were found to be significantly higher in patients with metastatic disease than those with early stage disease 124.

The first report involving GRK3 in retinoblastoma progression dates to 2001. By measuring corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-stimulated intracellular cAMP production and PKA signaling pathway activation in Y-79 retinoblastoma cell line, Dautzenberg et al. found that GRK3 controlled desensitization of the CRF1 receptor. Because the CRF1 receptor is known to increase stress adaptation in cancer cells 125, decreased levels of GRK3 may be beneficial to cancer cell survival.

Finally, recent studies have shown that GRK3 is aberrantly expressed in oral squamous carcinoma cells. The mRNA expression levels of GRK3 in tumor samples from patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma were significantly higher than in normal tissues. This study suggests that high expression of GRK3 is associated with oral squamous cell carcinoma tumorigenesis, possibly through the activation of β2-adrenergic receptor 126.

GRK4

GRK4 is expressed primarily in the testis, ovaries, brain, kidney, and myometrium 127. Due to the low-level expression of GRK4, there are few reports regarding its role in cancer. Several studies have shown that GRK4 modulates arterial angiotensin type 1 (AT1) and dopamine D receptor signaling 128, 129. In malignant ovarian granulosa cells, the expression of GRK4α/β was also found to be significantly lower than in benign granulosa cells 35. Silencing of GRK4α/β resulted in decreased kinase activity and impaired follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) desensitization. This desensitization may play a crucial role during ovarian granulosa cell transformation, although further investigation is required to fully discern the role of GRK4 in this process.

GRK5

GRK5 plays various roles during tumorigenesis. The expression of GRK5 is associated with worse prognosis in patients with stage II to IV glioblastoma. Kaur et al. showed that the levels of expression of GRK5 were significantly higher in high-grade primary and recurrent glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) than low-grade glioblastomas. The samples obtained from patients with recurrent diseases had higher GRK5 expression than tumor samples taken prior to recurrence. Knockdown of GRK5 was further shown to decrease the rate of proliferation and expression of stem cell markers in glioblastoma cells derived from a patient with GBM 130. Note, as previously discussed, GRK2 and GRK5 have opposite roles in thyroid cancer, as GRK2 inhibited the activity of the TSH receptor, while GRK5 promoted its activation 113.

In prostate cancer, it appears that increased expression of GRK5 correlates with tumorigenesis and oncogenesis. Silencing of GRK5 inhibited the proliferation of prostate cancer PC3 cells by decreasing the number of cells in G1 and increasing those in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle. These results suggest that GRK5 regulates cell cycle progression in prostate cancer cells 131. Other studies found that GRK5 was involved in migration, invasion, and cell adhesion of prostate cancer cells through a possible interaction with moesin, a protein known to regulate cell spreading. Overexpression of phosphomimetic moesin-T66D in PC3, DU145, and LNCaP prostate cancer cells significantly reduced cell migration through phosphorylation of moesin by GRK5. Moreover, expression of a phosphorylation-deficient moesin-T66A protein enhanced its activity 132. In vivo studies have also demonstrated that knockdown of GRK5 in mice with xenografted prostate cancer cells suppressed tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis 132, 133. Finally, it has been shown that GRK5 could directly phosphorylate P53 tumor suppressor in U2OS and Saos-2 osteosarcoma cells, and promote its degradation, thereby inhibiting tumor cell apoptosis 90.

GRK6

Studies investigating the function of GRK6 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using immunohistochemistry have demonstrated a positive correlation between GRK6 and Ki-67 expression, pathological disease stage, metastasis, and survival rate. These authors hypothesized that GRK6 could be used as a biomarker for the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma 134. Furthermore, recoverin, which is functionally associated with GRK6 (as well as GRK2 and GRK5), was aberrantly expressed in SSTW-2 gastric cancer cells 11.

GRK6 mRNA and protein expression was also found to be lower in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas than normal tissues 135. Cancer progression appears to be linked to aberrant methylation of GRK6, whose expression correlates with cancer cell invasion and disease stage. In vitro, GRK6 expression levels are elevated and invasion is inhibited in FaDu cells in response to 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine 135.

In medulloblastoma cells, PDGFR/Src signaling may mediate GRK6 activity to promote CXCR4 activation of CXCL12 with increased rate of cell migration 136.

GRK6 depletion also enhanced tumorigenesis and metastasis in a Lewis lung cancer mouse model, as MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression was significantly increased in GRK6-/- animals. Pharmacological inhibition of CXCR2 activation abrogated this effect in an NF-kB-dependent manner 85.

GRK inhibitors

Increased GRK expression levels are correlated with chronic or acute use of GPCR-targeted drugs. In a study investigating GPCR-targeted drug tolerance in the brain, it was shown that increased GRK expression might be responsible for drug resistance 137, 138. In addition, various pathological conditions such as heart failure, depression, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease are associated with the modulation of endogenous GRK expression 139-143. Because scientists are beginning to understand more about the biology of GPCR/GRK signaling in cancer, targeting GRKs are emerging as a new anticancer strategy. The most likely methods of developing highly selective GRK inhibitors will be to target their unique kinase domains or decrease GRK expression using selective RNA aptamers 144. To date, no effective GRK inhibitors have been approved for clinical practice 145. Because GRKs are a subfamily of AGC kinases, and their kinase domains are relatively similar in structure, nonselective GRK inhibitors may likely cross-react with other AGC kinases 146. However, one highly selective GRK2 inhibitor known as Takeda Compound 103A that inhibits GRK2 activity 50-fold more than other AGC kinases has been developed by Takeda Pharmaceuticals 147. Other highly selective drugs such as paroxetine (GRK2), GSK180736A (GRK3), balanol (GRK5), Takeda Compound 101 (GRK2), and sanigivamycin (GRK6) have been widely studied 148. Although they are reasonably selective for GRKs, they all show cross-reactivity with other kinases. The RNA aptamer, C13, first described by Mayer et al., 149 competes with the alkaloid, staurosporine, for the kinase domain binding on GRK2 without binding to the N- or C-terminus 144, 149. To our knowledge, the effective inhibitor targeted regions are frequently mutated in the population, limiting the drug's therapeutic potential 150.

Conclusion and perspectives

In conclusion, GRKs cooperate with arrestins and clathrin to control GPCR signaling. Because GPCRs and RTKs are the primary signal transducers of extracellular stimuli, GRKs act as important regulators to protect cells from overstimulation. Consequently, GRK activity could directly modulate the ability of endocrine hormones to influence the function of cells and tissues. In addition, GRKs help maintain homeostasis by inhibiting signal transduction and facilitating cellular communication in response to extracellular stress.

Recent studies have shown that GRK expression levels are implicated in almost every facet of cancer biology, from proliferation, invasion, and migration to metastasis and oncogenic transformation 151. Significant levels of GRK expression alternation in different cancers indicate that GRKs could be promising molecular targets to be considered to modulate GPCR responsiveness. Due to the heterogeneity of GRK structures, each one appears to play a different role in cancer progression. Investigation of the interesting contradictory roles of each subtype of GRKs may enable development of potent drugs that inhibit some isoforms but activate others for better disease control. GRKs regulate hundreds of unique GPCRs simultaneously, making it complex to fully discern how they modulate cellular signaling. As more GPCR-targeted anticancer therapies are developed, it is important to identify these mechanisms. Our current hypothesis suggests that GRKs primarily act as feedback loops that alter GPCR activity, especially for arrestin-biased signaling. Furthermore, targeting GRKs may result in unintended consequences with regard to the effects of GPCR-targeting drugs, and may induce drug resistance. Because GPCR signaling is becoming a more attractive topic in cancer pharmacology research 152, it is necessary for us to gather a full understanding of these GPCR-GRK interactions to inform more practical and efficient drug design and development. Collectively, pharmacological intervention of GRKs provides us with a novel concept in cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work and Leo T.O. Lee are supported by FDCT grant (FDCT101/2015/A3) from Macau government, Startup Research Grant (SRG2015-0048-FHS) and Multi-Year Research Grant (MYRG2016-00075-FHS) from University of Macau. L. Sun is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.81671689).

References

- 1.Katritch V, Cherezov V, Stevens RC. Structure-function of the G protein-coupled receptor superfamily. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:531–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-032112-135923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009;459:356–63. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Julius D, Nathans J. Signaling by sensory receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a005991. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang R, Xie X. Tools for GPCR drug discovery. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33:372–84. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lappano R, Maggiolini M. G protein-coupled receptors: novel targets for drug discovery in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:47–60. doi: 10.1038/nrd3320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heifetz A, Schertler GF, Seifert R, Tate CG, Sexton PM, Gurevich VV. et al. GPCR structure, function, drug discovery and crystallography: report from Academia-Industry International Conference (UK Royal Society) Chicheley Hall, 1-2 September 2014. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2015;388:883–903. doi: 10.1007/s00210-015-1111-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Congreve M, Marshall F. The impact of GPCR structures on pharmacology and structure-based drug design. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;159:986–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hothersall JD, Brown AJ, Dale I, Rawlins P. Can residence time offer a useful strategy to target agonist drugs for sustained GPCR responses? Drug Discov Today. 2016;21:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penela P, Murga C, Ribas C, Lafarga V, Mayor F Jr. The complex G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) interactome unveils new physiopathological targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:821–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00727.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyagawa Y, Ohguro H, Odagiri H, Maruyama I, Maeda T, Maeda A. et al. Aberrantly expressed recoverin is functionally associated with G-protein-coupled receptor kinases in cancer cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:669–73. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02888-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Y, Han CC, Huang Q, Sun WY, Wei W. GRK2 overexpression inhibits IGF1-induced proliferation and migration of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by downregulating EGR1. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:3068–74. doi: 10.3892/or.2016.4641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Billard MJ, Fitzhugh DJ, Parker JS, Brozowski JM, McGinnis MW, Timoshchenko RG. et al. G Protein Coupled Receptor Kinase 3 Regulates Breast Cancer Migration, Invasion, and Metastasis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurevich EV, Tesmer JJ, Mushegian A, Gurevich VV. G protein-coupled receptor kinases: more than just kinases and not only for GPCRs. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:40–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatakrishnan AJ, Deupi X, Lebon G, Tate CG, Schertler GF, Babu MM. Molecular signatures of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2013;494:185–94. doi: 10.1038/nature11896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurowitz EH, Melnyk JM, Chen YJ, Kouros-Mehr H, Simon MI, Shizuya H. Genomic characterization of the human heterotrimeric G protein alpha, beta, and gamma subunit genes. DNA Res. 2000;7:111–20. doi: 10.1093/dnares/7.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neves SR, Ram PT, Iyengar R. G protein pathways. Science. 2002;296:1636–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1071550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Premont RT, Macrae AD, Stoffel RH, Chung N, Pitcher JA, Ambrose C. et al. Characterization of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK4. Identification of four splice variants. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6403–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hall RA, Spurney RF, Premont RT, Rahman N, Blitzer JT, Pitcher JA. et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6A phosphorylates the Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor via a PDZ domain-mediated interaction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24328–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.24328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carman CV, Parent JL, Day PW, Pronin AN, Sternweis PM, Wedegaertner PB. et al. Selective regulation of Galpha(q/11) by an RGS domain in the G protein-coupled receptor kinase, GRK2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34483–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallese M, Mariggio S, D'Urbano E, Iacovelli L, De Blasi A. Selective regulation of Gq signaling by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2: direct interaction of kinase N terminus with activated galphaq. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57:826–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhami GK, Babwah AV, Sterne-Marr R, Ferguson SS. Phosphorylation-independent regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 signaling requires g protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 binding to the second intracellular loop. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24420–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501650200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pitcher JA, Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:653–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eichmann T, Lorenz K, Hoffmann M, Brockmann J, Krasel C, Lohse MJ. et al. The amino-terminal domain of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 is a regulatory Gbeta gamma binding site. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8052–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204795200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorkin A, von Zastrow M. Endocytosis and signalling: intertwining molecular networks. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:609–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beautrait A, Michalski KR, Lopez TS, Mannix KM, McDonald DJ, Cutter AR. et al. Mapping the putative G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) docking site on GPCR kinase 2: insights from intact cell phosphorylation and recruitment assays. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:25262–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibson TJ, Hyvonen M, Musacchio A, Saraste M, Birney E. PH domain: the first anniversary. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:349–53. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang DS, Shaw R, Winkelmann JC, Shaw G. Binding of PH domains of beta-adrenergic receptor kinase and beta-spectrin to WD40/beta-transducin repeat containing regions of the beta-subunit of trimeric G-proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:29–35. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribas C, Penela P, Murga C, Salcedo A, Garcia-Hoz C, Jurado-Pueyo M. et al. The G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) interactome: role of GRKs in GPCR regulation and signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1768:913–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Willets JM, Challiss RA, Nahorski SR. Non-visual GRKs: are we seeing the whole picture? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:626–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ambrose C, James M, Barnes G, Lin C, Bates G, Altherr M. et al. A novel G protein-coupled receptor kinase gene cloned from 4p16.3. Hum Mol Genet. 1992;1:697–703. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.9.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sallese M, Mariggio S, Collodel G, Moretti E, Piomboni P, Baccetti B. et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK4. Molecular analysis of the four isoforms and ultrastructural localization in spermatozoa and germinal cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10188–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virlon B, Firsov D, Cheval L, Reiter E, Troispoux C, Guillou F. et al. Rat G protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK4: identification, functional expression, and differential tissue distribution of two splice variants. Endocrinology. 1998;139:2784–95. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.6.6078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King DW, Steinmetz R, Wagoner HA, Hannon TS, Chen LY, Eugster EA. et al. Differential expression of GRK isoforms in nonmalignant and malignant human granulosa cells. Endocrine. 2003;22:135–42. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:22:2:135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hargrave PA, McDowell JH. Rhodopsin and phototransduction: a model system for G protein-linked receptors. FASEB J. 1992;6:2323–31. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1544542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kohout TA, Lefkowitz RJ. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins during receptor desensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:9–18. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nobles KN, Xiao K, Ahn S, Shukla AK, Lam CM, Rajagopal S. et al. Distinct phosphorylation sites on the beta(2)-adrenergic receptor establish a barcode that encodes differential functions of beta-arrestin. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra51. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiter E, Marion S, Robert F, Troispoux C, Boulay F, Guillou F. et al. Kinase-inactive G-protein-coupled receptor kinases are able to attenuate follicle-stimulating hormone-induced signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;282:71–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Homan KT, Tesmer JJ. Structural insights into G protein-coupled receptor kinase function. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;27:25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lodowski DT, Pitcher JA, Capel WD, Lefkowitz RJ, Tesmer JJ. Keeping G proteins at bay: a complex between G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and Gbetagamma. Science. 2003;300:1256–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1082348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black JB, Premont RT, Daaka Y. Feedback regulation of G protein-coupled receptor signaling by GRKs and arrestins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;50:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Penela P, Ribas C, Mayor F Jr. Mechanisms of regulation of the expression and function of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. Cell Signal. 2003;15:973–81. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Z, Jiang Y, Li Y, Wang J, Fan L, Scott MJ. et al. TLR4 Signaling augments monocyte chemotaxis by regulating G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 translocation. J Immunol. 2013;191:857–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Watari K, Nakaya M, Kurose H. Multiple functions of G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Mol Signal. 2014;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hausdorff WP, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Turning off the signal: desensitization of beta-adrenergic receptor function. FASEB J. 1990;4:2881–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pao CS, Benovic JL. Phosphorylation-independent desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors? Sci STKE. 2002;2002:pe42. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.153.pe42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sitaramayya A, Liebman PA. Phosphorylation of rhodopsin and quenching of cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase activation by ATP at weak bleaches. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:12106–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rockman HA, Choi DJ, Rahman NU, Akhter SA, Lefkowitz RJ, Koch WJ. Receptor-specific in vivo desensitization by the G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9954–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pippig S, Andexinger S, Daniel K, Puzicha M, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. et al. Overexpression of beta-arrestin and beta-adrenergic receptor kinase augment desensitization of beta 2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3201–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dawson TM, Arriza JL, Jaworsky DE, Borisy FF, Attramadal H, Lefkowitz RJ. et al. Beta-adrenergic receptor kinase-2 and beta-arrestin-2 as mediators of odorant-induced desensitization. Science. 1993;259:825–9. doi: 10.1126/science.8381559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sallese M, Salvatore L, D'Urbano E, Sala G, Storto M, Launey T. et al. The G-protein-coupled receptor kinase GRK4 mediates homologous desensitization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1. FASEB J. 2000;14:2569–80. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0072com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weiss ER, Ducceschi MH, Horner TJ, Li A, Craft CM, Osawa S. Species-specific differences in expression of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) 7 and GRK1 in mammalian cone photoreceptor cells: implications for cone cell phototransduction. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9175–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09175.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rinner O, Makhankov YV, Biehlmaier O, Neuhauss SC. Knockdown of cone-specific kinase GRK7 in larval zebrafish leads to impaired cone response recovery and delayed dark adaptation. Neuron. 2005;47:231–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ruiz-Gomez A, Mayor F Jr. Beta-adrenergic receptor kinase (GRK2) colocalizes with beta-adrenergic receptors during agonist-induced receptor internalization. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9601–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiina T, Arai K, Tanabe S, Yoshida N, Haga T, Nagao T. et al. Clathrin box in G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33019–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100140200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mangmool S, Haga T, Kobayashi H, Kim KM, Nakata H, Nishida M. et al. Clathrin required for phosphorylation and internalization of beta2-adrenergic receptor by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) J Biol Chem. 2006;281:31940–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodman OB Jr, Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gurevich VV, Penn RB, Gagnon AW. et al. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–50. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of beta-arrestins in the termination and transduction of G-protein-coupled receptor signals. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:455–65. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Banday AA, Fazili FR, Lokhandwala MF. Insulin causes renal dopamine D1 receptor desensitization via GRK2-mediated receptor phosphorylation involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase C. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F877–84. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00184.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naga Prasad SV, Barak LS, Rapacciuolo A, Caron MG, Rockman HA. Agonist-dependent recruitment of phosphoinositide 3-kinase to the membrane by beta-adrenergic receptor kinase 1. A role in receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18953–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pampillo M, Camuso N, Taylor JE, Szereszewski JM, Ahow MR, Zajac M. et al. Regulation of GPR54 signaling by GRK2 and {beta}-arrestin. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:2060–74. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sanchez-Mas J, Guillo LA, Zanna P, Jimenez-Cervantes C, Garcia-Borron JC. Role of G protein-coupled receptor kinases in the homologous desensitization of the human and mouse melanocortin 1 receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:1035–48. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.von Zastrow M. Role of endocytosis in signalling and regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:500–4. doi: 10.1042/bst0290500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marchese A, Paing MM, Temple BR, Trejo J. G protein-coupled receptor sorting to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:601–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fan X, Gu X, Zhao R, Zheng Q, Li L, Yang W. et al. Cardiac beta2-Adrenergic Receptor Phosphorylation at Ser355/356 Regulates Receptor Internalization and Functional Resensitization. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chiu YT, Chen C, Yu D, Schulz S, Liu-Chen LY. Agonist-dependent and -independent kappa opioid receptor phosphorylation showed distinct phosphorylation patterns and resulted in different cellular outcomes. Mol Pharmacol; 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kuhar JR, Bedini A, Melief EJ, Chiu YC, Striegel HN, Chavkin C. Mu opioid receptor stimulation activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase 2 by distinct arrestin-dependent and independent mechanisms. Cell Signal. 2015;27:1799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim J, Ahn S, Ren XR, Whalen EJ, Reiter E, Wei H. et al. Functional antagonism of different G protein-coupled receptor kinases for beta-arrestin-mediated angiotensin II receptor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1442–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409532102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Busillo JM, Armando S, Sengupta R, Meucci O, Bouvier M, Benovic JL. Site-specific phosphorylation of CXCR4 is dynamically regulated by multiple kinases and results in differential modulation of CXCR4 signaling. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7805–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.091173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ren XR, Reiter E, Ahn S, Kim J, Chen W, Lefkowitz RJ. Different G protein-coupled receptor kinases govern G protein and beta-arrestin-mediated signaling of V2 vasopressin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409534102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heitzler D, Durand G, Gallay N, Rizk A, Ahn S, Kim J. et al. Competing G protein-coupled receptor kinases balance G protein and beta-arrestin signaling. Mol Syst Biol. 2012;8:590. doi: 10.1038/msb.2012.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gao J, Li J, Ma L. Regulation of EGF-induced ERK/MAPK activation and EGFR internalization by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2005;37:525–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao J, Li J, Chen Y, Ma L. Activation of tyrosine kinase of EGFR induces Gbetagamma-dependent GRK-EGFR complex formation. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:122–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cote RH. Characteristics of photoreceptor PDE (PDE6): similarities and differences to PDE5. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(Suppl 1):S28–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wan KF, Sambi BS, Tate R, Waters C, Pyne NJ. The inhibitory gamma subunit of the type 6 retinal cGMP phosphodiesterase functions to link c-Src and G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 in a signaling unit that regulates p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase by epidermal growth factor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:18658–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sarnago S, Elorza A, Mayor F Jr. Agonist-dependent phosphorylation of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) by Src tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:34411–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Y, Long H, Wu Z, Jiang X, Ma L. EGF transregulates opioid receptors through EGFR-mediated GRK2 phosphorylation and activation. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2973–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Freedman NJ, Kim LK, Murray JP, Exum ST, Brian L, Wu JH. et al. Phosphorylation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta and epidermal growth factor receptor by G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2. Mechanisms for selectivity of desensitization. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48261–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Peppel K, Jacobson A, Huang X, Murray JP, Oppermann M, Freedman NJ. Overexpression of G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 in smooth muscle cells attenuates mitogenic signaling via G protein-coupled and platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Circulation. 2000;102:793–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.7.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cai X, Wu JH, Exum ST, Oppermann M, Premont RT, Shenoy SK. et al. Reciprocal regulation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta and G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 by cross-phosphorylation: effects on catalysis. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:626–36. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hildreth KL, Wu JH, Barak LS, Exum ST, Kim LK, Peppel K. et al. Phosphorylation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta by G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 reduces receptor signaling and interaction with the Na(+)/H(+) exchanger regulatory factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:41775–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wei Z, Hurtt R, Gu T, Bodzin AS, Koch WJ, Doria C. GRK2 negatively regulates IGF-1R signaling pathway and cyclins' expression in HepG2 cells. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228:1897–901. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zheng H, Worrall C, Shen H, Issad T, Seregard S, Girnita A. et al. Selective recruitment of G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) controls signaling of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7055–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118359109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raghuwanshi SK, Smith N, Rivers EJ, Thomas AJ, Sutton N, Hu Y. et al. G Protein-Coupled Receptor Kinase 6 Deficiency Promotes Angiogenesis, Tumor Progression, and Metastasis. The Journal of Immunology. 2013;190:5329–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barker BL, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylation of hip regulates internalization of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6933–41. doi: 10.1021/bi2005202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Penela P, Rivas V, Salcedo A, Mayor F Jr. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) modulation and cell cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1118–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905778107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ho J, Cocolakis E, Dumas VM, Posner BI, Laporte SA, Lebrun JJ. The G protein-coupled receptor kinase-2 is a TGFbeta-inducible antagonist of TGFbeta signal transduction. EMBO J. 2005;24:3247–58. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Carman CV, Som T, Kim CM, Benovic JL. Binding and phosphorylation of tubulin by G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20308–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chen X, Zhu H, Yuan M, Fu J, Zhou Y, Ma L. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylates p53 and inhibits DNA damage-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12823–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pronin AN, Morris AJ, Surguchov A, Benovic JL. Synucleins are a novel class of substrates for G protein-coupled receptor kinases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26515–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ruiz-Gomez A, Humrich J, Murga C, Quitterer U, Lohse MJ, Mayor F Jr. Phosphorylation of phosducin and phosducin-like protein by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29724–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cant SH, Pitcher JA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2-mediated phosphorylation of ezrin is required for G protein-coupled receptor-dependent reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3088–99. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Martini JS, Raake P, Vinge LE, DeGeorge BR Jr, Chuprun JK, Harris DM. et al. Uncovering G protein-coupled receptor kinase-5 as a histone deacetylase kinase in the nucleus of cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12457–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803153105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.So CH, Michal AM, Mashayekhi R, Benovic JL. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 phosphorylates nucleophosmin and regulates cell sensitivity to polo-like kinase 1 inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17088–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.353854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barthet G, Carrat G, Cassier E, Barker B, Gaven F, Pillot M. et al. Beta-arrestin1 phosphorylation by GRK5 regulates G protein-independent 5-HT4 receptor signalling. EMBO J. 2009;28:2706–18. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mardin BR, Agircan FG, Lange C, Schiebel E. Plk1 controls the Nek2A-PP1gamma antagonism in centrosome disjunction. Curr Biol. 2011;21:1145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rivas V, Carmona R, Munoz-Chapuli R, Mendiola M, Nogues L, Reglero C. et al. Developmental and tumoral vascularization is regulated by G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4714–30. doi: 10.1172/JCI67333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Robinson JD, Pitcher JA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) is a Rho-activated scaffold protein for the ERK MAP kinase cascade. Cell Signal. 2013;25:2831–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang Y, Matkovich SJ, Duan X, Gold JI, Koch WJ, Dorn GW 2nd. Nuclear effects of G-protein receptor kinase 5 on histone deacetylase 5-regulated gene transcription in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:659–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.111.962563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Dehvari N, Hutchinson DS, Nevzorova J, Dallner OS, Sato M, Kocan M. et al. beta(2)-Adrenoceptors increase translocation of GLUT4 via GPCR kinase sites in the receptor C-terminal tail. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:1442–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01647.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Patial S, Saini Y, Parvataneni S, Appledorn DM, Dorn GW 2nd, Lapres JJ. et al. Myeloid-specific GPCR kinase-2 negatively regulates NF-kappaB1p105-ERK pathway and limits endotoxemic shock in mice. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:627–37. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Penela P, Ribas C, Aymerich I, Eijkelkamp N, Barreiro O, Heijnen CJ. et al. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 positively regulates epithelial cell migration. EMBO J. 2008;27:1206–18. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Z. Transactivation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor by G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Recent Progress, Challenges and Future Research. Int J Mol Sci; 2016. p. 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Almendro V, Garcia-Recio S, Gascon P. Tyrosine kinase receptor transactivation associated to G protein-coupled receptors. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1169–80. doi: 10.2174/138945010792006807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Burch ML, Getachew R, Osman N, Febbraio MA, Little PJ. Thrombin-mediated proteoglycan synthesis utilizes both protein-tyrosine kinase and serine/threonine kinase receptor transactivation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:7410–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J. et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–28. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kamato D, Bhaskarala VV, Mantri N, Oh TG, Ling D, Janke R. et al. RNA sequencing to determine the contribution of kinase receptor transactivation to G protein coupled receptor signalling in vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0180842. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhang H, Li S, Doan T, Rieke F, Detwiler PB, Frederick JM. et al. Deletion of PrBP/delta impedes transport of GRK1 and PDE6 catalytic subunits to photoreceptor outer segments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8857–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701681104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang H, Frederick JM, Baehr W. Unc119 gene deletion partially rescues the GRK1 transport defect of Pde6d (- /-) cones. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;801:487–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-3209-8_62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yamamoto S, Sippel KC, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Defects in the rhodopsin kinase gene in the Oguchi form of stationary night blindness. Nat Genet. 1997;15:175–8. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]