Abstract

Long informed consent forms (ICFs) remain commonplace, yet they can negatively affect potential participants’ understanding of clinical research. We aimed to build consensus among six groups of key stakeholders on advancing the use of shorter ICFs in clinical research. Partnering with the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN), we used a modified Delphi process with semi-structured interviews and online surveys. Concerns about redundancy of information were common. Respondents supported three strategies for reducing ICF length: 1) 91% agreed or strongly agreed with grouping study procedures by frequency, 2) 91% were comfortable or very comfortable with placing supplemental information into appendices, and 3) 93% agreed or strongly agreed with listing duplicate side effects only once. Implementing these strategies will facilitate adoption of the proposed changes to U.S. regulations on ICF length, should they be enacted.

Keywords: informed consent, consent forms, research ethics, U.S. regulations, HIV

Introduction

Proposed changes to the U.S. regulations that govern human subjects research address the longstanding, problematic issue of lengthy informed consent forms (ICFs) in clinical research. The Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) states, “Consent forms would no longer be able to be unduly long documents, with the most important information often buried and hard to find. They would need to give appropriate details about the research that is most relevant to a person’s decision to participate in the study, such as information a reasonable person would want to know, and present that information in a way that highlights the key information” (NPRM, 2015).

Despite evidence demonstrating that long ICFs can negatively affect potential participants’ understanding of research (Epstein & Lasagna, 1969; Beardsley, Jefford, & Mileshkin, 2007), the length of ICFs has increased over time (Beardsley et al., 2007; Albala, Doyle, & Appelbaum, 2010: LoVerde, Prochazka, & Byyny, 1989; Berger, Gronberg, Sand, Kaasa, & Loge, 2009) and long ICFs remain commonplace (Beardsley et al., 2007; Albala et al, 2010). Shorter ICFs have been shown to be as effective (Enama, Hu, Gordon, Costner, Ledgerwood, & Grady, 2012; Stunkel et al., 2010) or better (Beardsley et al., 2007; Dresden & Levitt, 2001; Matsui, Lie, Turin, & Kita, 2012) than long ICFs at providing relevant information and enhancing potential participants’ understanding, yet evidence on the non-inferiority of shorter consent forms has not led to widespread changes in ICF length.

We engaged key stakeholders in a consensus-building process for advancing the use of shorter ICFs in clinical research. We partnered with two HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) clinical studies to conduct the research: HPTN 069 [NCT01505114], which assessed the safety and tolerability of four drug regimens used as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV transmission in women and men who have sex with men (HPTN 069, 2012); and HPTN 073 [NCT018083520], which assessed the initiation, acceptability, safety, and feasibility of PrEP for Black men who have sex with men (HPTN 073, 2013). In this article, we describe three strategies for reducing ICF length and how they were empirically developed and supported.

Methods

Study population

Six groups of stakeholders were purposively sampled. We engaged HPTN participants who were currently or recently enrolled in HPTN 069 or HPTN 073 in four U.S. cities: Boston, MA; Chapel Hill, NC; and Los Angeles and San Francisco, CA. We also engaged the following “research stakeholders”: HPTN scientists and staff (i.e., protocol chairs, site investigators, site staff, operations center staff), community representatives (i.e., members of community advisory boards [CABs] and the HPTN community working group [CWG]), institutional officials (i.e., individuals involved in research oversight or policies related to informed consent), members of sites’ institutional review boards (IRBs), and staff at the Division of AIDS (DAIDS) at the National Institutes of Health who were involved in the oversight of the ICF process for HPTN studies.

Data collection

We used a three-step, modified Delphi process (Hasson, Keeney, & McKenna, 2000) to build consensus on advancing the use of shorter ICFs, expanding upon a similar process used in developing consent language for biobanking (Beskow, Dombeck, Thompson, Watson-Ormond, & Weinfurt, 2015). We began with individual, semi-structured interviews (SSIs), followed by two online surveys with a sub-set of stakeholders from the SSIs.

In the SSIs, respondents reviewed one of four HPTN site-specific ICFs (three from HPTN 069 and one from HPTN 073) sentence by sentence on an iPad. HPTN participants, HPTN scientists and staff, IRB members, institutional officials, and CAB members reviewed the site-specific ICF from their affiliated site; HPTN CWG members and DAIDS staff each reviewed one of the four site-specific ICFs, which were divided equally among them. Respondents electronically highlighted sentences in green if they believed they were essential for informed decision making. Respondents highlighted sentences in red when they believed information could be excluded without having a negative effect on informed decision making. Respondents left sentences un-highlighted when the sentences did not fit into either category. At the end of each ICF section, respondents described the rationale for their highlighting choices. We also asked respondents several additional open-ended questions, depending on their stakeholder group. Questions included their overall impression of the ICF they reviewed for the study, perceptions of reducing ICF length in general, barriers faced in reducing ICF length, and potential solutions for overcoming the barriers. Interviews were audio-recorded, with the respondents’ permission.

Next, in the first survey, we presented respondents with findings from the initial SSIs. We also created and provided specific examples to illustrate the potential strategies for reducing ICF length, by modifying text from a site-specific ICF. We asked all respondents to comment on these examples, using both closed- and open-ended questions, indicating whether they supported a particular strategy; for research stakeholders, we asked whether they anticipated any barriers to implementing this strategy in future studies. The closed-ended questions typically used four-level Likert responses. All HPTN scientists and staff and DAIDS staff who agreed to be contacted for the first survey were invited to participate. We also invited a subset of HPTN participants, community representatives, institutional officials, and IRB members to participate based on their interest and the richness of the information they provided in the SSIs.

Finally, in the second survey we presented findings from the first survey, and asked respondents closed-and open-ended questions to identify potential solutions for overcoming the barriers previously identified. We also asked questions to further explore respondents’ support of the strategies after they learned the perspectives of other respondents; response options were presented using a four-point Likert scale. All respondents who completed the first survey were invited to participate in the second survey.

Data analysis

Numerous analytical methods were used. First, we conducted a content analysis of all four site-specific ICFs, both to quantify the overall lengths of the forms and to identify the longest sections. Second, we used a systematic process for analyzing the sentence-by-sentence review of the ICFs (see supplemental information).

Third, we used applied thematic analysis (Guest, MacQueen, & Namey, 2011) to analyze the open-ended questions asked during the SSIs. Interview text was initially structurally coded, based on interview questions, by a single analyst in order to segment data on the same topic. The same analyst then identified the major themes and subthemes within each structural code, which were subsequently verified by a different analyst. There were no major discrepancies between analysts during these reviews; minor discrepancies were discussed and data categories or groupings were adjusting accordingly. The salience of the themes and subthemes within and across all stakeholder groups for a specific code were described in summary reports, together with illustrative quotes.

Fourth, using the findings from the sentence-to-sentence review, we ranked all sentences in each site-specific ICF from most essential to least essential. For the sentences identified as less essential, we analyzed responses to the open-ended questions to identify why sentences were perceived as less important, following a similar process as described above. We also analyzed respondents’ rationales for deciding sentences were less important in some of the longest sections in the ICFs (e.g., study procedures). Reasons for suggesting that particular sentences could be removed from the ICF were summarized. Suggestions for strategies to reduce ICF length emerged from these and other discussions in the SSIs.

Finally, we used descriptive statistics to examine responses to the survey’s closed-ended questions. Answers from HPTN participants and research stakeholders were initially disaggregated during analysis but are combined here when similar. For the open-ended responses to survey questions, a single analyst grouped and summarized responses by overall themes and subthemes, based on their frequency among HPTN participants and research stakeholders.

Ethics statement

We received ethics approvals from the IRBs at each participating site, Johns Hopkins Medicine, and the Protection of Human Subjects Committee at FHI 360. All respondents provided their oral consent to participate.

Results

Here we refer to stakeholders as “respondents” when data from all stakeholders (HPTN participants and research stakeholders) are combined. When we present disaggregated data for the two groups of respondents, we refer to the respondents as either HPTN participants or research stakeholders. A total of 100 respondents participated in the SSIs; 53 respondents participated in the first survey and 43 in the second survey (Table 1). Respondent demographics are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Number of respondents for each round of data collection, by stakeholder group.

| Initial SSI | Survey | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Group | First | Second | |

| HPTN participants | 42 | 16 | 15 |

| Research stakeholders | 58 | 37 | 28 |

| HPTN protocol chairs, site investigators, site staff, operations center staff | 20 | 14 | 10 |

| Community representatives | 11 | 6 | 4 |

| Institutional officials | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| IRB members | 12 | 8 | 7 |

| DAIDS representatives | 9 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 100 | 53 | 43 |

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of respondents who participated in the SSI.

| Demographic variable | HPTN Participants (N=42) |

Research Stakeholders (N=58) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yr*, n (%) | ||

| 19–25 | 12 (28.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| 26–35 | 9 (21.4) | 6 (10.7) |

| 36–45 | 6 (14.3) | 18 (32.1) |

| ≥46 | 15 (35.7) | 31 (55.4) |

| Declined | 0 0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Race†, n (%) | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Asian | 1 (2.4) | 1 (1.7) |

| Black or African American | 14 (34.1) | 10 (17.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 23 (56.1) | 47 (81.0) |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 39 (92.9) | 55 (94.8) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Female | 5 (11.9) | 32 (55.2) |

| Male | 36 (85.7) | 26 (44.8) |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Highest level of education completed, n (%) | ||

| Eighth grade or equivalent or less | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some high school | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 4 (9.5) | 1 (1.7) |

| Vocational/trade/technical school | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 14 (33.3) | 3 (5.2) |

| Finished college | 17 (40.5) | 12 (20.7) |

| Masters or other advanced degree | 3 (7.1) | 42 (72.4) |

| Current student status‡,§, n (%) | ||

| Not a student | 33 (82.5) | -- |

| Current employment status‡, n (%) | ||

| Employed full-time | 18 (42.9) | -- |

| Employed part-time | 10 (23.8) | -- |

| Self-employed | 1 (2.4) | -- |

| Unemployed or between jobs | 10 (23.8) | -- |

| On disability | 2 (4.8) | -- |

| Other | 1 (2.4) | -- |

Data missing from two research stakeholders

Data missing from one HPTN study participant

Asked only of the HPTN participants

Data missing from two HPTN participants

ICF length

The lengths of the four site-specific ICFs (not including the signature pages) ranged from 16 to 21 pages. The number of sentences (not including the subject headers) ranged from 429 to 523, and the number of words (including headers) ranged from 8,537 to 9,096. In each site-specific ICF, the longest content area was study procedures, followed by risks and confidentiality (Table 3).

Table 3.

Length of the site-specific informed consent forms, by content area.

| Content Area of ICF | Number of Sentences in Site-Specific ICF |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPTN 069 | HPTN 073 | |||

| Site A | Site B | Site C | Site D | |

| Study procedures | 166 | 155 | 160 | 173 |

| Risks – study medication | 87 | 83 | 84 | 43 |

| Risks – other | 56 | 54 | 57 | 39 |

| Confidentiality | 41 | 44 | 40 | 27 |

| Previous studies | 36 | 17 | 36 | 22 |

| General research ethics* | 24 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Research design | 25 | 25 | 25 | 1 |

| My part in the research† | 12 | 17 | 12 | 16 |

| Benefits | 13 | 11 | 14 | 14 |

| Sample storage‡ | 8 | 30 | 5 | 27 |

| Purpose and objectives | 11 | 8 | 12 | 4 |

| Compensation | 4 | 12 | 9 | 4 |

| Study reference info§ | 2 | 2 | 11 | 0 |

| Study alternatives | 9 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Injury | 10 | 6 | 7 | 9 |

| Exclusion criteria | 4 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| Clinicaltrials.gov | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Study contact | 6 | 3 | 5 | 12 |

| Funding | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Stop study drugs‖ | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 523 | 493 | 516 | 429 |

Includes statements about general ethical principles, typically found at the beginning of the consent form (e.g., the study is research, research is voluntary)

Includes statements about the participant’s roles or responsibilities as part of the study, excluding the study procedures

Sites could include detailed information about sample storage either in the main consent or in a separate consent; sites B and D included this information in the main consent

Includes general reference information from the study (e.g., title, IRB #, DAIDS #, protocol version)

Includes a description of what happens in the case of a participant stopping the medication

Almost all research stakeholders agreed or strongly agreed in the first survey that ICFs are generally too long (95%, n=35) (Table 4). Most respondents who reviewed an HPTN 069 ICF agreed or strongly agreed that the ICF was too long (89%, n=39), although fewer respondents who reviewed an HPTN 073 ICF shared this belief (56%, n=5). Almost all respondents agreed or strongly agreed (96%, n=51) that ICFs should be made shorter, as long as the essential information is retained.

Table 4.

Responses for the first and second online surveys, by HPTN participants and research stakeholders.

| HPTN participants | Research stakeholders | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Survey, n (%) | HPTN 069, n=14 |

HPTN 073, n=2 |

HPTN 069, n=30 |

HPTN 073, n=7 |

Total, n=53* |

| ICFs are generally too long | |||||

| Strongly agree | -- | -- | 13 (43.3) | 3 (42.9) | 16 (43.2) |

| Agree | -- | -- | 16 (53.3) | 3 (42.9) | 19 (51.4) |

| Disagree | -- | -- | 1 (3.3) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (5.4) |

| Strongly disagree | -- | -- | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| ICF reviewed for EDICT was too long | |||||

| Strongly agree | 2 (14.3) | 0 (0) | 12 (40.0) | 2 (28.6) | 16 (30.2) |

| Agree | 8 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 17 (56.7) | 3 (42.9) | 28 (52.8) |

| Disagree | 4 (28.4) | 1 (50.0) | 1 (3.3) | 2 (28.6) | 8 (15.1) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| As long as the essential information is retained, ICFs should be made shorter in length | |||||

| Strongly agree | 8 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 22 (73.3) | 4 (57.1) | 34 (64.2) |

| Agree | 5 (35.7) | 2 (100.0) | 8 (26.7) | 2 (28.6) | 17 (32.1) |

| Disagree | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (3.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strategy 1: Group study procedures by frequency instead of by study visit | |||||

| Strongly agree | 8 (57.1) | 0 (0) | 18 (60.0) | 5 (71.4) | 31 (58.5) |

| Agree | 5 (35.7) | 1 (50.0) | 6 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | 13 (24.5) |

| Disagree | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 6 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (15.1) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Anticipated challenges with grouping study procedures by frequency | |||||

| Yes | -- | -- | 13 (43.3) | 5 (71.4) | 18 (48.6) |

| No | -- | -- | 17 (56.7) | 2 (28.6) | 19 (51.4) |

| Strategy 2: Provide reference information about specific study procedures in appendix† | |||||

| Strongly agree | 9 (64.3) | 1 (50.0) | 10 (34.5) | 1 (16.7) | 21 (41.2) |

| Agree | 1 (7.1) | 1 (50.0) | 12 (41.4) | 3 (50.0) | 17 (33.3) |

| Disagree | 3 (21.4) | 0 (0) | 4 (13.8) | 1 (16.7) | 8 (15.7) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (10.3) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (9.8) |

| Anticipated challenges with providing reference information about study procedures in appendix† | |||||

| Yes | -- | -- | 14 (48.3) | 3 (50.0) | 17 (48.6) |

| No | -- | -- | 15 (51.7) | 3 (50.0) | 18 (51.4) |

| Strategy 3: List duplicative side effects once rather than listing all side effects for each drug‡ | |||||

| Strongly agree | 7 (50.0) | -- | 15 (50.0) | -- | 22 (50.0) |

| Agree | 3 (21.4) | -- | 10 (33.3) | -- | 13 (29.5) |

| Disagree | 3 (21.4) | -- | 5 (16.7) | -- | 8 (18.2) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (7.1) | -- | 0 (0) | -- | 1 (2.3) |

| Anticipated challenges with listing duplicative side effects once | |||||

| Yes | -- | -- | 24 (82.8)§ | -- | 24 (82.8) |

| No | -- | -- | 5 (17.2) | -- | 5 (17.2) |

| HPTN participants | Research stakeholders | ||||

| Second Survey, n (%) |

HPTN 069, n=13 |

HPTN 073, n=2 |

HPTN 069, n=22 |

HPTN 073, n=6 |

Total, n=43 |

| Strategy 1 | |||||

| Challenges to grouping study procedures by frequency can be overcome | |||||

| Strongly agree | 8 (61.5) | 0 (0) | 12 (54.5) | 1 (16.7) | 21 (48.8) |

| Agree | 3 (23.1) | 2 (100) | 10 (45.5) | 3 (50.0) | 18 (41.9) |

| Disagree | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (7.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) |

| Grouping study procedures by frequency should be recommended for shortening ICFs | |||||

| Strongly agree | 9 (69.2) | 0 (0) | 20 (90.9) | 3 (50.0) | 32 (74.4) |

| Agree | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (16.3) |

| Disagree | 1 (7.7) | 2 (100) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (9.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strategy 2 | |||||

| Comfort level with placing supplemental information in appendices | |||||

| Very comfortable | 8 (61.5) | 0 (0) | 14 (63.6) | 1 (16.7) | 23 (53.5) |

| Comfortable | 5 (38.5) | 1 (50) | 7 (31.8) | 3 (50.0) | 16 (37.2) |

| Uncomfortable | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (33.3) | 4 (9.3) |

| Very uncomfortable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Comfort level with not requiring potential participants to read appendix before signing ICF | |||||

| Very comfortable | 6 (46.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (31.8) | 1 (16.7) | 14 (32.6) |

| Comfortable | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 9 (40.9) | 2 (33.3) | 14 (32.6) |

| Uncomfortable | 4 (30.8) | 2 (100) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (50.0) | 12 (27.9) |

| Very uncomfortable | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (7.0) |

|

Study procedures examples provide information necessary for informed decision making in ICF body and provide information not needed for informed decision making in appendix | |||||

| Strongly agree | 7 (53.8) | 1 (50) | 13 (59.0) | 1 (16.7) | 22 (51.2) |

| Agree | 5 (38.5) | 1 (50) | 8 (36.4) | 4 (66.7) | 18 (41.9) |

| Disagree | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (7.0) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Strategy 3 | |||||

| Challenges to listing duplicative side effects once can be overcome | |||||

| Strongly agree | 5 38.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 1 (16.7) | 8 (18.6) |

| Agree | 8 (61.5) | 2 (100) | 20 (90.9) | 4 (66.7) | 34 (79.1) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (2.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Listing duplicative side effects once should be recommended for shortening ICFs | |||||

| Strongly agree | 10 (76.9) | 1 (50) | 15 (68.2) | 2 (33.3) | 28 (65.1) |

| Agree | 2 (15.2) | 0 (0) | 7 (31.8) | 3 (50.0) | 12 (27.9) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (4.7) |

Unless otherwise noted by clarifying missing data or identifying when respondents were not asked the question

Data missing from one HPTN 069 and one HPTN 073 research stakeholder

HPTN 073 study participants and research stakeholders were not asked initially about this strategy because that study provided only one drug

Data missing from one stakeholder

Essential and extraneous information

The supplemental information describes findings on the essential and extraneous information identified by respondents. Overall, research stakeholders marked a considerable amount of information in the ICFs as “non-essential” or “neutral” (i.e., sentences left un-highlighted) whereas HPTN participants generally marked fewer sentences as “non-essential” or “neutral”.

Stakeholder impressions of the ICFs

“Repetitive” was the most common description given by respondents when they provided their impressions of the ICFs during the initial SSIs, followed by “too detailed” and “laborious.” Although some respondents described being generally satisfied with the ICF, narratives focused on the repetitive wording of the ICFs far more than any other description. In addition, responses similar to “repetitive” were commonly given when participants described their rationale for marking sentences as “nonessential” or “neutral.” An IRB member explained:

You're saying the same thing, on multiple pages, [but] just saying [it] a little different. Especially like with all those medications.

Concerns about redundancy and suggestions to reduce it were frequently discussed throughout the SSIs: synonyms of the word “redundant” were stated 1,100 times by respondents and interviewers. An HPTN participant said:

Yeah. They just [keep] repeating themselves. A normal person that understands English and would pick up on the first time that they said it. They don’t have to repeat it. If they want to save themselves some paper and ink, there’s some stuff you just get rid of. You don’t need it.

Strategies to reduce ICF length

Three strategies for reducing the length of ICFs were supported by respondents’ narratives in the SSIs. Data describing all of the participants’ support for these strategies, as reported in the follow-up surveys, are found in Table 4.

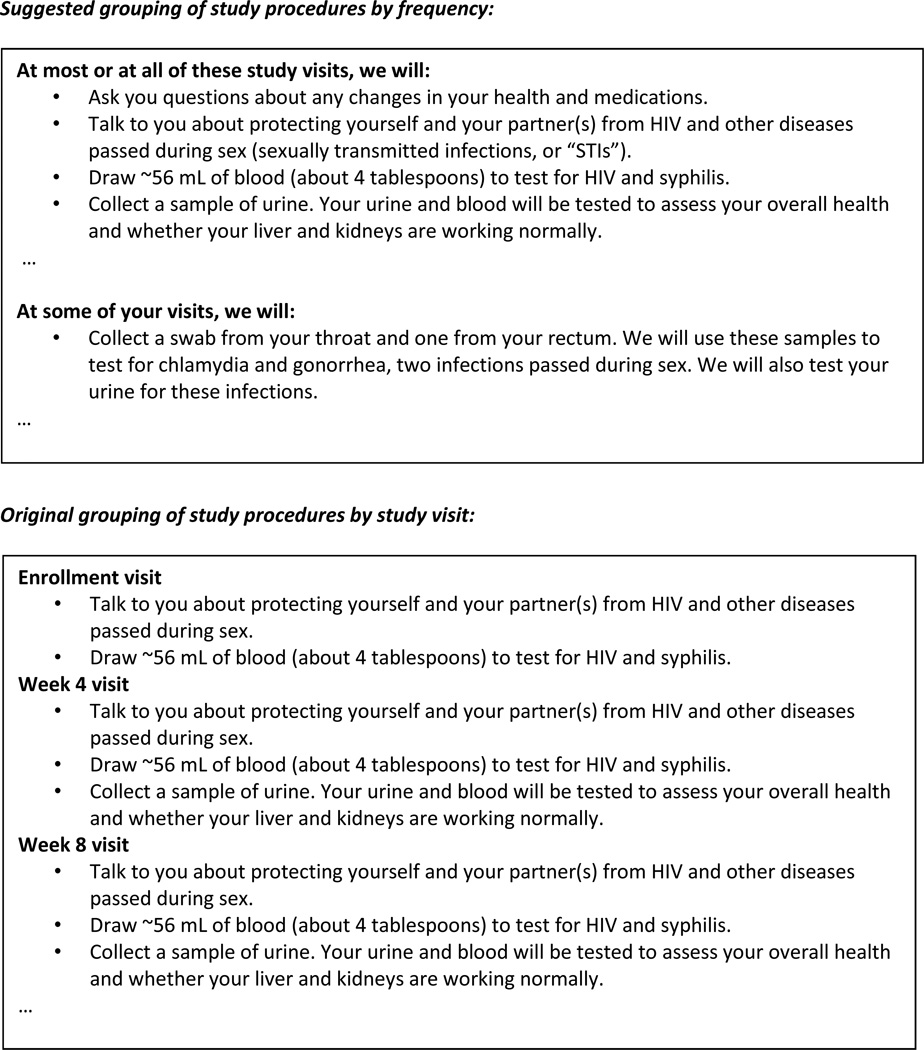

Strategy 1: Grouping study procedures by frequency

The first strategy is grouping study procedures by frequency instead of by study visit (Fig. 1). The rationale for this strategy was described by an HPTN study participant in the SSIs:

First of all, the blow-by-blow of what happens on different weeks is utterly ridiculous. Nobody is going to say, ‘Oh, well I see at Week 16, you’ll be collecting urine. I’m sorry. I can’t participate in any study where urine is collected in an even-numbered week.’ Nobody cares what happens at the various visits. So you could probably reduce this to conservatively a quarter of the size, and probably an eighth of the size, just by saying ‘Here are the types of things that happen at the various visits. Now there’ll be some special visits when we’ll want to do a bone scan and this and that.’

Fig. 1.

Illustrative example of grouping study procedures by frequency instead of by study visit.

Through the content analysis, we documented that listing each study procedure by visit week led to multiple repetitions of the same information and was a contributing factor to why this section was the longest of the ICFs. For example, the following statement was included seven times in one site-specific ICF: “For women of childbearing potential: Collect urine for pregnancy testing.” The following statement was written five times: “Give you a brief physical exam, ask you if you have experienced any side effects from the study drugs, and ask you about any other medicines you are taking.” By employing the strategy of grouping study procedures by their frequency and writing procedures simply, we reduced the study procedures section of this site-specific ICF from 2,645 words and 5 pages to 993 words and 2 pages, a reduction of 1,652 words and 3 pages; in other words, the revised version had 62% fewer words and 60% fewer pages.

After viewing this revised section during the first survey, 88% (n=14) of study participants and 81% (n=30) of research stakeholders strongly agreed or agreed with grouping study procedures by frequency as a strategy for reducing ICF length. Many supported this strategy because it provided all necessary information in one place, making the ICF easier and quicker to read. An HPTN participant said:

I was able to understand the two-page form faster since they were grouped by commonalities rather than weeks which stretch out so far that I wouldn't really process what's going on [during] week 49. It is much better to list the commonalities among all the visits and have the shorter form.

Respondents who did not support this strategy said it was important for participants to know what to expect at each study visit and thought the revised approach was not or was only slightly easier to read.

Almost half of research stakeholders (49%, n=18) in the first survey anticipated barriers in implementing this strategy, primarily the reluctance of researchers to make such changes and the “rigidness” of IRBs to accept new approaches. Research stakeholders explained that the visit-by-visit approach is the IRB’s long-standing preference and their mindset must change before any improvements can be made. Most respondents (91%, n=39), however, strongly agreed or agreed in the second survey that these barriers can be overcome. An IRB member said:

I think there would be less IRB resistance to this idea than people think.

After viewing all respondents’ answers from the first survey, 91% of respondents (n=39) indicated in the second survey that grouping study procedures by frequency should be recommended for shortening ICFs.

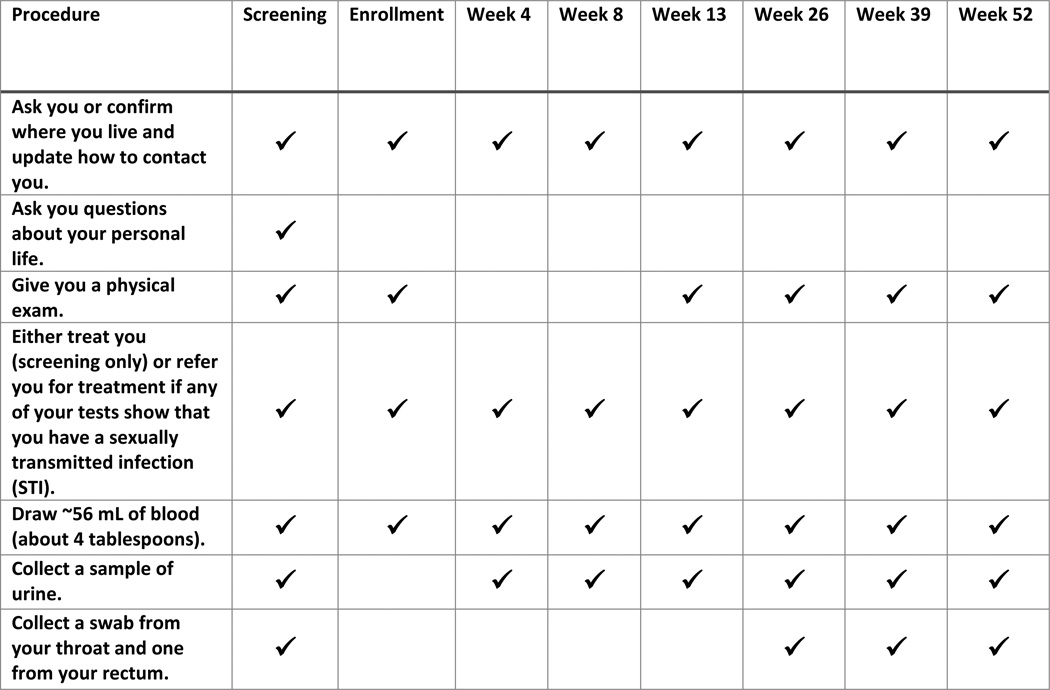

Strategy 2: Using appendices

The second strategy is moving detailed, supplemental information from the body of the ICF to appendices. The rationale for this strategy was described by a DAIDS staff member in the SSIs:

…as many times as they repeat things in the document, some of that stuff should be pulled out, should be put in an appendix…What good is it for them to take home a 19-page document if they can’t find what they need in it?

As an example of how this strategy could be implemented in an ICF, respondents during the first survey viewed and commented on a visit schedule of study procedures as an appendix (details about specific study procedures conducted at each study visit were moved from the ICF body and placed into an appendix as a table; Fig. 2.) Seventy-five percent (n=38) of respondents in the first survey strongly agreed or agreed with this approach. Many said that moving detailed, repetitive information to the appendix makes the information in the ICF easier to read, understand, and reference later. Several added that they supported the use of appendices because the ICF body should include only the main points, as too much detail is distracting and overwhelming. An HPTN participant explained:

On the first day when you're going through all of the paperwork, it's a bit overwhelming. Having concise language that I learn first, and then an appendix that I can refer to later (if needed) is perfect.

Fig. 2.

Sample appendix listing study procedures by each study visit.

Several also said that appendices were an effective method for providing detailed information, for those who want it, and that the example visit schedule in the appendix was concise and easy to understand. An institutional official said:

In studies with numerous site visits of varying lengths, the consent form often becomes a confusing wasteland of days and times that could be captured more effectively in a detailed table that is outside of the body of the main consent.

Respondents who did not support this approach explained that potential participants would still need to review the information and therefore there would be no difference in the length of time to obtain consent. Some also believed important information for informed decision making would be lost and, therefore, thought the details should remain in the ICF body.

Almost half of research stakeholders in the first survey (49%, n=17), foresaw challenges with moving the details of the visit schedule to an appendix. Many believed IRBs and other reviewers would view appendices unfavorably because they are a new and less detailed approach, making approval difficult to obtain. Several also said that regulators want pertinent information in the body of the ICF and not in appendices.

In the second survey, after considering all respondents’ views from the first survey, 91% (n=39) of respondents reported they were comfortable or very comfortable with placing supplemental information into appendices (“supplemental” information was defined as information that provides additional detail to the content provided in the main ICF; no new topics would be introduced). Respondents explained that this approach allows the important, uncluttered information to remain in the body of the ICF while supplemental or less important information is provided in the appendix. A community representative said:

In another way of thinking about it, maybe ‘need to know’ goes in the text and ‘nice to know’ goes in the appendix. Additional ‘nice to know’ info can clog up and distract from the focus of the discussion in the main text.

Fewer respondents (65%, n=28) in the second online survey, although the majority, were comfortable with not requiring potential participants to read the appendices prior to signing the consent form. As described by an HPTN affiliate:

If it’s important enough to be included in the ICF, then it should be important enough for a participant to review as part of their decision making. The intent should be to make the information easier to review.

Ultimately, 93% (n=40) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed in the second survey that combining Strategy 1 — grouping study procedures by frequency in the body of the ICF — with Strategy 2 — using a table for the visit schedule in an appendix — keeps information necessary for informed decision making in the ICF body and provides reference information not needed for informed decision making in the appendix.

Strategy 3: Aggregating drug side effects

The third strategy is listing duplicative side effects of study drugs only once, instead of listing them multiple times. The rationale for this strategy was described by a community representative in the SSIs:

…when you talk about the different study medications that are being used and the side effects, I think if you have a general statement saying, ‘The following side effects have been found in all of the study medications’ and list what they are, then with each study medication, list what the [other] specific side effects could be. I think that would make it stronger because it would say ‘Fever, weight loss, sleeplessness, dizziness’ pretty much practically is the side effect of every medication that you take.

By employing the strategy of listing duplicative side effects once, as well as eliminating other repetitive information and stating information more simply, we reduced the study medication section in one HPTN 069 site specific consent form from 944 words and 2.5 pages to 622 words and 1.5 pages, a reduction of 322 words and 1 page; in other words, the revised version had 34% fewer words and 40% fewer pages.

After viewing this revised section during the first survey, 83% (n=25) of research stakeholders and 71% (n=10) of HPTN study participants agreed or strongly agreed with listing duplicative side effects once (only HPTN 069 respondents were asked this question because the HPTN 073 study had only one drug). Respondents explained that this strategy made information on side effects clearer, simpler for participants, and easier to understand. An HPTN affiliate said:

[This strategy] is more concise and clear when presenting the side effects. Going down each list of individual medications, saying the same effects several times, the participants starts to tune out…This is shorter, and they can ask questions if they want to know more about specific side effects.

Several also said this strategy provides enough information for informed decision making and for letting participants know what to expect.

Among those who did not support this strategy in the first survey, concern was expressed that participants need to know as much as possible and that drugs should be kept separate because they have different contraindications.

Eighty-three percent (n=24) of research stakeholders reported in the first survey that they anticipated barriers in implementing this strategy. Four main barriers were described: 1) it is a standard practice to list all side effects and that “old habits are hard to break”; 2) the ICF is a legal document and listing the side effects for each drug separately provides protection from liability; 3) reviewers expect to see the details for each study drug; and 4) it will be time-consuming, more difficult, and complicated for the investigator to distill the information. However, in the second survey, 98% (n=42) of research stakeholders believed these barriers can be overcome.

After viewing all responses from the first survey, 93% (n=40) of respondents indicated in the second survey that listing duplicate side effects once should be recommended for shortening ICFs.

Discussion

We used an empirically-driven, consensus-building approach that led to the support of three strategies for reducing the length of ICFs by a large majority of stakeholders actively involved in clinical research in HIV prevention. The content of information described in the ICFs was generally viewed as important by many of the HPTN participants, yet narratives about redundancy of information in ICFs were pervasive among all stakeholders. In response, the three strategies—grouping procedures by frequency, using appendices, and aggregating drug side effects—focused on methods that retain the important information for informed decision making but reduce repetition. Barriers to implementing these strategies were identified, but they were perceived to be surmountable. The same degree of consensus was not reached about whether information placed in appendices—an approach supported by the proposed changes in the NPRM—should be read together with information in the ICF body or whether it should be considered additional, reference information that potential participants are not required to read before signing the consent from.

The desire for shorter ICFs was also documented in a review of public comments on the Advance NPRM (ANPRM) (proposed changes to the U.S. regulations governing research that preceded the NPRM) (NPRM, 2015). Reviewers’ comments were consistent with our findings and suggested that two areas were contributing factors to the excessive length of ICFs: the listing of all reasonably foreseeable risks and the complexity of study procedures. These areas overlap with two of the three longest ICF content areas identified in this study—study procedures, risks, and confidentiality—and overlap with sections that have been previously identified as the longest sections in ICFs of DAIDS-funded research (Kass, Chaisson, Taylor, & Lohse, 2011).

A strength of our study is that we used actual ICFs currently in use for two HPTN studies and engaged a diverse group of stakeholders who were meaningfully involved with those ICFs, thus diminishing concerns that our study might be too hypothetical. In addition, rather than simply editing the ICFs to be shorter, we empirically captured aspects that stakeholders believed were contributing to ICF length and elicited reactions to original and modified ICF language, an approach that generated empirically-supported recommendations for restructuring ICFs for concision. We also obtained consensus in a manner that permitted confidentiality, helping to ensure authentic responses. However, the actual number of ICFs and research sites was small (n=4), as was the number of parent studies (n=2) and some respondent groups. Further, the study was conducted in English and among a highly educated group of HPTN participants. Although together these characteristics may limit the generalizability of our findings to other types of research, and to participants who are non-English speakers or who have lower levels of education, we were able to recommend empirically-based strategies for reducing the length of sections that are standard to ICFs used in all types of research; these strategies can be a starting point for future research with other study populations.

In conclusion, although these strategies have been utilized in some research studies, they are not commonly used in clinical research. Key stakeholders’ support of these strategies can advance the use of shorter ICFs in clinical research in HIV prevention, particularly given that these strategies focus on reducing the length of two of the longest sections of ICFs. Lastly, implementation of these strategies will facilitate adoption of the proposed changes to the U.S. regulations on ICF length, should they become enacted.

Best practices

Because the general structure of ICFs is similar across multiple areas of clinical research, we believe our findings have applicability in clinical research beyond HIV prevention. That is, the strategies empirically derived inform our work can likely be applied to reduce the length of ICFs in medical fields other than HIV. For example, those responsible for developing ICFs for clinical research can transition from listing study procedures by study visits—which can result in repeatedly describing the same procedure in a single ICF—to grouping study procedures by frequency, thereby describing the study procedure only once and reducing the length of the ICF. As stated above, the strategies discussed here have been used previously in some research studies to reduce the length of ICFs. Unfortunately, they are not commonly used, perhaps due to the concerns that we identified and described above. However, in our research those concerns were also perceived to be surmountable. We encourage those responsible for developing ICFs to use these data to promote the use of shorter ICFs within their own research studies.

Research agenda

Our approach to advancing the use of shorter ICFs in clinical research is multi-faceted. Our efforts began with the research described in this manuscript—the use of an empirically-driven, consensus-building process that resulted in the support of three strategies to reduce the length of ICFs by six key stakeholder groups. This support provides the empirical evidence necessary to proceed to the next stage—the evaluation of these strategies. Future research should compare ICFs incorporating these three strategies to standard-of-care ICFs in a randomized control trial embedded within actual clinical research studies. Potential participants’ understanding of the study and satisfaction with the informed consent process as well as time saved by using a shorter process can be measured and compared between the two arms.

If such research demonstrates an advantage over longer ICFs, additional work is still necessary to advance the use of shorter ICFs in clinical research. As described in the introduction, evidence already exists that shorter ICFs have been shown to be as effective as or better than long ICFs at providing relevant information and enhancing potential participants’ understanding. Yet, longer consent forms remain commonplace. Moving forward, focus should be placed on determining what types of activities (e.g., advocacy using the evidence that supports the use of shorter ICFs, or additional research on shorter ICFs) are necessary to reach a tipping point regarding the length of ICFs among those who develop, approve, and implement them.

Educational implications

Challenges of the informed consent process have been documented in the scholarly literature and disseminated through academic and ethics conferences for decades. However, long and complicated ICFs are still commonly used. New dialogue, informed by data, is needed. We must focus less on documenting and disseminating the limitations of the informed consent process and more on promoting promising approaches to overcoming such challenges when obtaining informed consent.

Educational efforts should emphasize the support demonstrated here and elsewhere on strategies to reduce the length of ICFs and to encourage key stakeholders to feel comfortable in using and approving shorter ICFs. Educational efforts should stress the multiple groups of stakeholders who support strategies for shortening ICFs. In our study, these stakeholders were diverse and comprehensive: study participants, investigators and study staff, community representatives, institutional officials, members of the IRB, and regulatory representatives. Practically, investigators and study staff who develop ICFs must be aware of strategies to reduce ICF length, feel comfortable using these strategies to create short ICFs in their studies, and advocate for the use of short ICFs when submitting their research studies for IRB approval. Study participants and community representatives should demand shorter ICFs that can facilitate the decision-making process about study participation among potential participants rather than hinder it. IRB members and regulatory representatives must be aware of and feel comfortable approving such strategies and require shorter ICFs for the research studies that they review and approve. Sustained and widespread change in the length of ICFs used in clinical research is likely to occur only when multiple and diverse stakeholders demand such change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative of the HPTN participants and research stakeholders who participated in the research and to the additional study staff who helped develop and implement the research: Ansley Lemons, Kevin McKenna, Natalie Eley, Justin Dash, and Chris Van Hasselt. We also thank the HPTN 069 and HPTN 073 study teams for their generous assistance in conducting the initial interviews.

Funding: The research was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, under award number R56AI100695. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

- There are no conflicts of interest.

- Some of the data reported in this manuscript were presented at the Advancing Research Ethics Conference, sponsored by Public Responsibility in Medicine and Research (PRIM&R), November 12–15, 2015, Boston, MA.

References

- Albala I, Doyle M, Appelbaum PS. The evolution of consent forms for research: a quarter century of changes. IRB. 2010;32:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley E, Jefford M, Mileshkin L. Longer consent forms for clinical trials compromise patient understanding: so why are they lengthening? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:e13–e14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger O, Gronberg BH, Sand K, Kassa S, Loge JH. The length of consent documents in oncological trials is doubled in twenty years. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:379–385. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beskow LM, Dombeck CB, Thompson CP, Watson-Ormond, Weinfurt K. Informed consent for biobanking: consensus-based guidelines for adequate comprehension. Genet Med. 2015;17:226–233. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresden GM, Levitt MA. Modifying a standard industry clinical trial consent form improves patient information retention as part of the informed consent process. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:246–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enama ME, Hu Z, Gordon I, Costner P, Ledgerwood JE, Grady C. Randomization to standard and concise informed consent forms: development of evidence-based consent practices. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:895–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LC, Lasagna L. Obtaining informed consent. Form or substance. Arch Intern Med. 1969;123:682–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HPTN 069: A Phase II Randomized, Double-Blind, Study of the Safety and Tolerability of Maraviroc (MVC), Maraviroc + Emtricitabine (MVC+FTC), Maraviroc + Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (MVC+TDF), or Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate + Emtricitabine (TDF+FTC) for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) to Prevent HIV Transmission in At-Risk Men Who Have Sex with Men and in At-Risk Women. 2012 Retrieved from: https://www.hptn.org/research/studies/110.

- HPTN 073: Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Initiation and Adherence among Black Men who have Sex with Men (BMSM) in Three U.S. Cities. 2013 Retrieved from: https://www.hptn.org/research/studies/136.

- Kass NE, Chaisson L, Taylor HA, Lohse J. Length and complexity of US and international HIV consent forms from federal HIV network trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1324–1328. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1778-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoVerde ME, Prochazka AV, Byyny RL. Research consent forms: continued unreadability and increasing length. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:410–412. doi: 10.1007/BF02599693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui K, Lie RK, Turin TC, Kita Y. A randomized controlled trial of short and standard-length consent forms for a genetic cohort study: is longer better? J Epidemiol. 2012;22:308–316. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NPRM for Revisions to the Common Rule. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 2015 Retrieved from: http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/regulations/nprmhome.html.

- Stunkel L, Benson M, McLellan L, Sinaji N, Bedairda G, Emanuel E, Grady C. Comprehension and informed consent: assessing the effect of a short consent form. IRB. 2010;32:1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.