Abstract

Objective

To describe and explain stroke survivors and informal caregivers’ experiences of primary care and community healthcare services. To offer potential solutions for how negative experiences could be addressed by healthcare services.

Design

Systematic review and meta-ethnography.

Data sources

Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsycINFO databases (literature searched until May 2015, published studies ranged from 1996 to 2015).

Eligibility criteria

Primary qualitative studies focused on adult community-dwelling stroke survivors’ and/or informal caregivers’ experiences of primary care and/or community healthcare services.

Data synthesis

A set of common second order constructs (original authors’ interpretations of participants’ experiences) were identified across the studies and used to develop a novel integrative account of the data (third order constructs). Study quality was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist. Relevance was assessed using Dixon-Woods’ criteria.

Results

51 studies (including 168 stroke survivors and 328 caregivers) were synthesised. We developed three inter-dependent third order constructs: (1) marginalisation of stroke survivors and caregivers by healthcare services, (2) passivity versus proactivity in the relationship between health services and the patient/caregiver dyad, and (3) fluidity of stroke related needs for both patient and caregiver. Issues of continuity of care, limitations in access to services and inadequate information provision drove perceptions of marginalisation and passivity of services for both patients and caregivers. Fluidity was apparent through changing information needs and psychological adaptation to living with long-term consequences of stroke.

Limitations

Potential limitations of qualitative research such as limited generalisability and inability to provide firm answers are offset by the consistency of the findings across a range of countries and healthcare systems.

Conclusions

Stroke survivors and caregivers feel abandoned because they have become marginalised by services and they do not have the knowledge or skills to re-engage. This can be addressed by: (1) increasing stroke specific health literacy by targeted and timely information provision, and (2) improving continuity of care between specialist and generalist services.

Systematic review registration number

PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015026602

Introduction

Globally, stroke is the second leading cause of death and the third most important cause of disability burden.[1, 2] Stroke-related disability burden is on the rise with a 12% increase worldwide since 1990. This rise accounts for more than 100 million Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost (> 2 million in the USA alone, 0.66 in the UK) and contributes to the large economic burden of stroke due to healthcare utilisation, informal care and the loss of productivity (for example, DALYs of younger stroke survivors (<75 years old) account for 70% of DALYs lost).[1, 3] The cost of stroke is high and estimated at $33 billion (including health care cost, medicines and missed days of work)[4] in the USA, £8.9 billion per annum in the UK[3] and $5 billion in Australia (including healthcare, informal care and the loss of productivity).[5]

Primary care could play an important role in the care of stroke survivors and their caregivers, supporting access to community services, facilitating transfer back to specialist services when new problems emerge, providing training, respite care, and identifying and addressing health needs of caregivers, and managing those aspects of care that are traditionally managed in general practice (for example, risk factors and psychological issues). However, the feeling of abandonment that people with stroke experience following hospital discharge suggests this role is not being completely fulfilled.[6–8] Qualitative reports indicate that lack of co-ordinated post-discharge care leaves patients and informal caregivers feeling unsupported.[6, 8–12]

No comprehensive systematic review of stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ specific experiences of primary care and community healthcare services has been performed. Previous qualitative reviews offer a broader focus including experiences of acute services[13] or are more selective, omitting research focussed on specific problem areas (e.g. information provision[14]). Meta-ethnography may offer new insight into how post-discharge care after stroke could be improved by providing a conceptual framework which surpasses simple aggregation of primary findings.[15] Our aim was to synthesise qualitative evidence on community-dwelling stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ experiences of primary care and community healthcare services after stroke in order to explain where these experiences originate from and how they could be addressed by healthcare services and interventions.

Methods

Search strategy

A review protocol has been previously published[16] (PROSPERO 2015:CRD42015026602). Searches of four electronic databases (Medline, CINAHL, Embase and PsycINFO) were conducted by NAZ and VH between May and June 2015 (see appendix A) using PICo mnemonics[17]:

Population included stroke survivors and family caregivers

Interest focused on experiences, perspective, satisfaction and needs

Context included primary care, community health services and general practice

Caregivers were defined as unpaid carers, including spouse or partner, family members, friends, or significant others who provide physical, practical, transportation or emotional help [16]. Keywords relevant to the study type (qualitative, interview, focus group) were included. No date, language or country restrictions were applied, but we did not include non-English language papers in the synthesis; references of eligible articles were checked for relevance.

Study selection and data collection

We included studies that used qualitative methods of data collection and analysis, and described the experiences of adult (≥ 18 years old) community-dwelling stroke survivors and/or informal caregivers of primary care and community healthcare services after stroke.[16] Community healthcare services included district nurses, community rehabilitation services (e.g., physiotherapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT))[18], speech and language therapist (SLT) and clinical psychology. We excluded papers which: 1) used mixed-methods designs where the qualitative data could not be separated; 2) included multiple patient populations; 3) focused on the in-patient setting, nursing or residential homes, or 4) multiple settings (for example, hospital, early supported discharge, nursing homes, community setting) and did not distinguish between them in their analyses.[16] Descriptive data, quality assessment, themes identified by the authors and their description using author’s original language or a paraphrase were recorded for each paper in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by two independent reviewers.

Quality appraisal

Quality of included studies was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Research Checklist (CASP)[19] by two reviewers. Studies could achieve a maximum score of 10 points. We did not exclude studies based on CASP quality assessment, but used this as descriptive information to add to the critical analysis. Studies were rated for relevance using criteria introduced by Dixon-Woods et al.[20] This divided papers into four categories in relation to our research objectives. Firstly, key papers, were conceptually rich with potential to make an important contribution to the synthesis; Secondly, satisfactory papers had potential value to the synthesis. Studies which were deemed irrelevant to our objectives or to have fatal methodological flaws were excluded. A fatal flaw was a subjective assessment by the reviewer that the methodology was so poor that it was not appropriate to make use of the results. A third reviewer was consulted when consensus could not be reached.

Synthesis

We used meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative studies.[21] Meta-ethnography is particularly well-suited to provide new insights into understanding the experiences of stroke survivors and their caregivers as it provides a conceptual framework which surpasses simple aggregation of primary findings.[15, 22] We adopted a paradigm neutral approach and synthesised studies based on their thematic rather than theoretical similarity.[23, 24]

Our unit of analyses were themes identified by the authors of included studies (i.e. second order constructs reflecting authors’ interpretations of primary data, namely participants’ accounts which constituted first order constructs[15]). Three groups of two reviewers (DMP, NA, VH, AVR, IW, RM, LL) read a subset of papers and recorded second order constructs with brief descriptions in the authors’ own words. Contextual details were recorded (aim, country of origin, sample characteristics, study setting, data collection and analysis methods). DMP and RM interpretatively read and compared second order constructs across the studies, and summarised them into second order constructs shared by the studies (Table 1). The summary included descriptions “that had a meaning for all the studies [which included a relevant theme]” ([15], p. 161). We then grouped the second order constructs into categories reflecting key characteristics of post-discharge care: (1) continuity of care, (2) access to services, (3) information and (4) quality of communication (Fig 1).

Table 1. Second and third order constructs.

| Third order constructs | Second order constructs | Papers | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived marginalisation | ||||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| The need for greater continuity of care | Lack of support and feeling abandoned; no individual plan; waiting time between hospital discharge and initiating therapy in the home. Caregivers stress the need for ongoing support (essential) and felt that the stroke survivor was going backwards while waiting for community rehab services. Caregivers also wanted to know how they could initiate some form of rehabilitation. Absence of longer term reassessment by allied healthcare professionals was apparent, however some survivors were generally satisfied and very appreciative of services of PTs, OTs, and speech and language therapists (SLTs). Those with improvements had no opportunity to access further therapeutic advice. Significant gaps in services provided while longer rehabilitation (PT) was wanted. Little help from social or specialist services or little contact with the hospital. | [8–10, 27, 28, 36, 38, 39, 47, 54, 55] | ||

| Access | ||||

| Lack of much needed support | Limited or lack of support in all areas e.g. help to get organised and establish a routine; emotional and social support; insufficient or quickly diminished support. Levels of support should be maintained throughout the caregivers’ career; worries about what might happen if caregiver gets ill; felt they had to become experts in caring role. | [6, 25–28] | ||

| Caregivers’ perceptions of a good therapy service | A good therapy has to bring an improvement in physical functioning of stroke survivors. The lack of individualised treatment perceived as a problem by both a stroke survivor and a caregiver. Dissatisfaction with quality of services, for example, too low intensity of community inpatient rehabilitation after discharge, rehabilitation was unspecific (mostly included walks); dissatisfaction with healthcare professional-patient and family communication which was perceived as too negative. | [12, 29–32] | ||

| Understanding of individual needs | Services did not always understand the person with stroke as an individual, some preferred to access culturally specific or mainstream services, not always acknowledged by services | [33] | ||

| Exercise potentially beneficial but access to physiotherapy preferred | Exercise (e.g. exercise referral scheme, a part of a secondary prevention programme with goal setting) brought physical and psychological improvements, increased physical activity (PA), fitness, strength and movement (ER), and improved ability to do activities of daily living (ADLs) plus increased participation (Masterstroke programme). However, survivors want more individualised care, i.e. more PT rather than exercise in the gym. | [34–36] | ||

| Lack of vocational support to return to work | Younger survivors (mean age 49 years) were very disappointed with the lack of support from community services to return to work. | [37] | ||

| Caregivers’ need for training* | Little preparation given to caregivers in relation to the hospital discharge of a stroke survivor which created panic and anxiety. Training mostly needed in practical caring skills, information on available support, help with form filling, training in advocacy skills and looking after their own health. | [6, 9, 25, 38–40] | ||

| Back-up and respite services for caregivers | Caregivers felt they needed support from services, including back-up services in emergencies and respite services. Services which provided respite included day hospital care; lack of resources in the community and the difficulty in identifying and accessing available resources as important barriers to continuing in the caregiving role. Caregivers’ state of health when planning support service needs to be considered. | [8, 9, 25, 28, 29, 40] | ||

| Help for caregivers from voluntary agencies and peers | Voluntary agencies important sources for information and equipment in the immediate post discharge phase. Support groups and a 12 week peer delivered intervention can contribute to decreased burden. | [6, 41, 42] | ||

| Information | ||||

| Information on stroke, its consequences and recovery | Information on stroke and risk of future stroke is of key importance. More education and explanations on stroke from healthcare professionals requested. Information on causes of stroke, effects of stroke and treatment decisions needed. When information provided (e.g. as part of living with Dysarthria or Masterstroke programmes) it was listed as a benefit. Sometimes information difficult to deal with as it brought back memories of stroke. More (and on-going) information needed on the trajectory of recovery and prognosis. Survivors questioned if the onset of strokes could have been prevented if healthcare professionals had had appropriate knowledge about stroke. | [25, 35, 37–39, 41, 43, 44–48] | ||

| Information on secondary prevention and concerns about medication | Information on secondary prevention was a priority. More information on secondary prevention and how to prevent another stroke wanted but little or no information received (e.g. in hospital). Some survivors did receive general lifestyle information including diet and exercise, most in written format and not reinforced verbally. Survivors had concerns about taking medication and its adverse effects and interactions. Concerns were reduced when no adverse effects experienced. | [11, 27, 49–51] | ||

| Communication | ||||

| Ineffective communication between healthcare providers, patient and family* | Systems of communication with a patient after discharge are necessary. Gaps in the transfer of knowledge between healthcare professionals were highlighted. Insufficient explanations about the treatment. Caregivers felt lack of confidence to speak to healthcare professionals. Language used to describe diagnosis caused confusion. Clinicians need to communicate effectively. | [29, 33, 38, 44, 47, 49, 52] | ||

| Quality of the relationship with healthcare professionals important† | Sympathy, empathy and understanding were valued. Healthcare professionals who seemed to be doing all they could and were easily approachable were valued. Having confidence in personnel and being a part of the planning of continued care important. | [12, 28, 53] | ||

| Passivity/activity | ||||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Dissatisfaction with the lack of follow-up and need for formal support* | Caregivers were disconcerted by the lack of hospital or a GP follow-up; they felt that stroke survivor was forgotten or written off. Dissatisfaction with the lack of monitoring from the healthcare system. Caregivers used stroke services, appreciated regular check-ups as reassurance. | [6–8, 10–12, 25, 29, 47] | ||

| Healthcare professionals who could facilitate continuity of care | GP, Family Support Organizer, social services, rehabilitation services (e.g. PT). | [6, 10, 11, 54, 55] | ||

| Access | ||||

| Support from healthcare professionals and community services facilitates recovery and social participation* | Survivors look for guidance in physical recovery, support with psychological, emotional or social issues, but little professional support was available. Healthcare professionals’ support at home as part of the improvements goal programme (including self-management and self-monitoring) was perceived as essential in improving self-care. Domiciliary rehabilitation services provided convenience and comfort, caregiver education and rehabilitation process geared towards their home environment. Community services (health & social services, community organisations) can act as either important facilitators or as barriers to social participation of survivors with aphasia. | [37, 44, 45, 56, 57] | ||

| Limited access* | Access to healthcare was jeopardized because of geographic distance or transportation difficulties. Another limiting factor was a mismatch between survivors’ expectations (e.g. community rehabilitation to address support with rehousing, transport, management of stress, emotional and interpersonal difficulties) and the remit of service. Therapy was needed earlier and for longer (e.g. PT, OT, SLT). Timing of home care services was crucial and the main reason to stop accessing the service even when it was felt that the service was needed. | [37, 38, 58] | ||

| Difficulties accessing health services | Delayed access or problems accessing services was highlighted; these included: rehabilitation services (PT, OT, SLT), social services, home care, equipment, supplies and financial assistance. Difficulty accessing appointments, cancellations, visits were too short. Navigating the field of community stroke care difficult. However, when early and continuing rehabilitation services were available, survivors appreciated practical advice from therapists during early rehabilitation. | [8, 26, 27, 37–39, 43, 50, 52, 59] | ||

| Community services much needed | The need for community services: home visit from healthcare personnel, domestic help, municipal nurse, (attendance at day centre). Not enough financial support and social services and psychological services. Services received from PTs, OTs and SLTs generally very appreciated. Services of Family Support Organizer were appreciated and provided regular check-ups as reassurance; continuity in knowledge and a valuable resource to turn to if things became “too much”. | [39, 40, 43, 55, 60, 61] | ||

| Help needed with benefits* | Problems completing benefit forms within deadlines for benefits agencies; knowing about how to apply for help with a problem. Information and help from a variety of sources (social services and voluntary agencies) was perceived as helpful. | [6, 28, 55] | ||

| Information | ||||

| Information on availability and access to services* | More and increasingly detailed information needed on what services are available in the community and how to access them. Services listed included: benefits, home adaptations, support groups, home help, equipment and the information on the roles of healthcare providers (e.g. differences between an OT and a social worker). Both survivors and caregivers were unaware of local stroke support groups which were potentially very important in helping them adjust. Caregivers wanted information on stroke associations, caregiver support groups, home help, future rehabilitation options or services, and community support facilities (e.g. hydrotherapy). | [10, 27, 28, 48, 55, 59, 62] | ||

| Methods of accessing information* | Uncertainty on how to access information. Caregivers accessed information from various sources: books, a doctor, leaflets from caregiver group, gained by chance (e.g. in a conversation). Survivors mentioned internet or voluntary organisations as sources. | [25, 37, 55] | ||

| Information format | Format of the information needs to be considered: both written and verbal information needed; written format not appropriate for survivors with aphasia. Courses by stroke unit and stroke groups perceived as highly relevant. Other useful formats of information provision: telephone contact with healthcare professional, drop in centre, face-to-face contact (preferred to telephone line for emotional support). Importance of availability, quick responses and personalised information. | [9, 11, 28, 38, 39, 51, 62] | ||

| The need for a coordinated information resource* | A single route to information, services, and practical help, whatever the problem, would make life easier. Having a resource folder as part of the course (Living with Dysarthria) was perceived as a fantastic resource. Caregivers felt that information was available but that they would need to know where to seek it and what to request. Caregivers accessed information from various sources: books, a doctor, leaflets from caregiver group, gained by chance (e.g. in a conversation). Survivors mentioned internet or voluntary organisations. Navigation of the healthcare system was difficult, as was knowing what resources were available and how to access them. | [25, 28, 45, 62] | ||

| Education as potential motivator to adherence to a lifestyle change | Patients struggle to adhere to treatment regimens (e.g. not drinking alcohol) despite encouragement from healthcare professionals. Reasons included: 1) questioning the value of healthy lifestyle (as it did not prevent stroke or due to changing information from health campaigns), or 2) home help service not facilitating healthy eating. For caregivers the perceived stress-relieving properties of alcohol and tobacco were a barrier to healthy lifestyle. However, education about diet and nutrition within a self-management programme could act as a motivator. | [35, 44, 51] | ||

| Preferred information provider | More information from healthcare professionals in general and a GP in particular. When information was provided by nurses, social workers and PTs, most caregivers (#12) were satisfied with information. PT; some preferred that information was provided by a doctor. | [10, 28, 44] | ||

| Change and fluidity of needs | ||||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Proactive follow-up expected from a GP† | Caregivers expected immediate and automatic GP follow-up for at least one year after discharge. In practice, very few caregivers reported GP follow-up. Some reported a total lack of contact with their GP. Routine contact with primary care would be appreciated. Many satisfied with the support from GP and practice nurses but some were disappointed with the lack of support from GP. Some perceived services as reactive. Caregivers usually described the contact with GP practice in relation to a stroke survivor rather than to themselves. | [6, 9, 11, 27, 28, 39] | ||

| Need for ongoing support from healthcare professionals† | Caregivers voiced the need for ongoing support also during adaptation phase (several months after stroke). However, none received any long term information and healthcare professionals did not discuss caregivers’ long term support needs. | [63] | ||

| Support needed with medication adherence at the time of transition to home† | Caregivers’ role in medication management; non-adherence at the point of transition from hospital to home due to forgetting, complex regimen, night-time dose. | [11] | ||

| Information | ||||

| Timing of the information | Information giving must be appropriate to the stage of recovery. Caregivers felt information was provided not in the right time. For example excess information in first few weeks, comments that they did not know what questions to ask at that point, and there had been no follow-up opportunity. Stroke survivors reported the need for information after the acute phase due to the difficulty in processing information at that time. | [6, 11, 28, 49, 51, 59, 63] | ||

* Themes relating to both perceived marginalisation and passive and active services

† Themes relating to change and the fluidity of needs as well as passive and active services. Key papers are marked in bold.

Fig 1. Inter-relationships among categories of second order constructs.

Finally, we developed third order constructs which represent our own explanation of why stroke survivors’ and caregivers’ had the experiences of primary care and community healthcare services that were represented in the second order constructs. We used the second order constructs as building blocks to develop these third order constructs and to make a ‘line of argument synthesis’ in which we could consider how the findings might inform a sustainable model of long term support [16] The process was iterative and involved a consultation exercise with qualitative and healthcare researchers with expertise in primary care and stroke.

Results

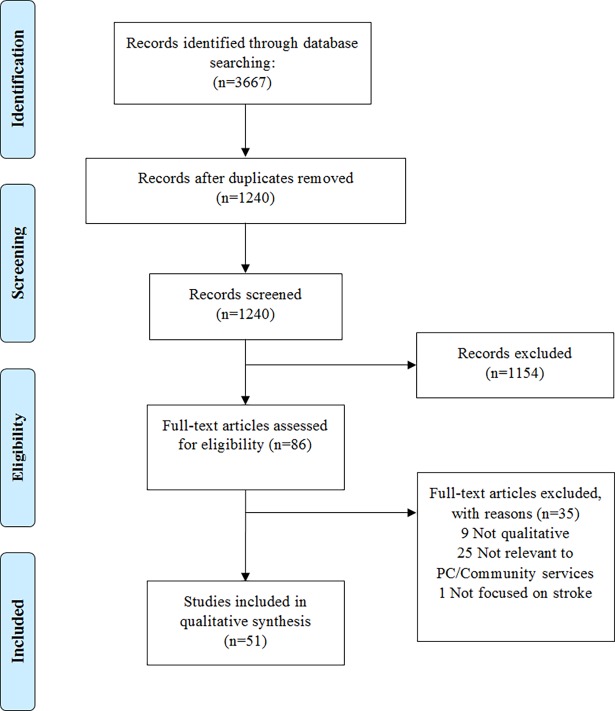

We identified 3,667 potentially relevant articles. After excluding duplicates, title and abstract screening, 86 full reports were read in full and assessed for eligibility. 51 papers representing 51 unique studies including 496 participants (168 stroke survivors and 328 informal caregivers) were included in the final synthesis (Fig 2).

Fig 2. PRISMA flow diagram of studies included and excluded at each stage of the review.

Study and participant characteristics are listed in Table 2. Almost half of studies (n = 20) included both stroke survivors and informal caregivers, and 17 studies included survivors from across the stroke continuum (within the first year after stroke n = 12, and beyond n = 12). Studies originated from the UK (25), North America (12), Australia (8) and Scandinavia (5), and one study was from Iran.[43] The majority of studies (n = 32) used interviews; eight used focus groups.

Table 2. Characteristics of the reviewed studies.

| Citation | Ref. | Country | Survivor / Caregiver | Participant characteristics Survivor / Caregiver n (n females), age range |

Analytical method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allison 2008 | [49] | England | Both | 25 (11) 37–91 years/13 (8) NR | Framework |

| Barnsley 2012 | [64] | Australia | Survivors | 19 (7) years | Open/axial coding |

| Blixen 2014 | [52] | USA | Both | 10 (0) 34–64 years/7 (7) 49–61 years | Constant comparative method |

| Brown 2011 | [65] | Australia | Caregivers | 24 (15) 40–87 years | Interpretive phenomenological analysis |

| Brunborg 2014 | [60] | Norway | Survivors | 9 (5) 61–96 years | Thematic coding |

| Burman 2001 | [66] | USA | Both | 13 (8) 28–85 years | Constant comparative method |

| Cameron 2013 | [63] | Canada | Caregivers | 24 (17) 36–77 years | Framework |

| Cecil 2011 | [38] | Northern Ireland | Caregivers | 10 (10) NR | Inductive method |

| Cecil 2013 | [39] | Northern Ireland | Caregivers | 30 (23) 36–84 years | Inductive method |

| Dalvandi 2010 | [43] | Iran | Survivors | 10 (4) 55–70 years | Open/axial/selective coding |

| Danzl 2013 | [61] | USA | Both | 13 (9) 42–89 years/12 (7) 38–75 years | Content analysis |

| Denman 1998 | [25] | England | Caregivers | 9 (6) NR | Thematic analysis |

| Donnellan 2013 | [44] | Northern Ireland | Survivors | 8 (2) 52–83 years | Content analysis |

| Dorze 2014 | [56] | Canada | Survivors | 19 (5) 51–84 years | Narrative analysis |

| Eaves 2002 | [58] | USA | Both | 8 (6) 56–79 years/18 (6) 21–70 years | Interpretive phenomenological analysis |

| El Masry 2013 | [29] | Australia | Both | 10 (2) 41–90 years/20 (16) 31–90 years | Thematic analysis (Kruger’s method*) |

| Gosman-Hedstrom 2012 | [67] | Sweden | Caregivers | 16 (16) 74–86 years | Constant comparative method |

| Grant 1996 | [26] | USA | Both | 10 (NR) 45–82 years/10 (9) 32–68 years | Inductive method |

| Graven 2013 | [68] | Australia | Both | 8 (2) 58–89 years/6 (5) 49–75 years | Thematic analysis |

| Greenwood 2011 | [9] | England | Caregivers | 13 (8) NR | Constant comparative method |

| Hare 2006 | [27] | England | Both | 27 (13) 43–88 years/6 (6) NR | Thematic analysis |

| Hart 1999 | [54] | England | Both | 57 (25) ~65–85 years | Framework |

| Jones 2008 | [50] | England | Both | 35 (NR) 25–92 years/20 (NR) NR | Thematic analysis |

| Law 2010 | [59] | Scotland | Survivors | 14 (6) 33–76 years | Framework |

| Lawrence 2010 | [51] | Scotland | Both | 29 (13) 37–81 years/20 (9) 42–79 years | Thematic analysis |

| Lilley 2003 | [55] | England | Survivors | 20 (NR) Mean = 63 years | Content analysis |

| Low 2004 | [30] | England | Caregivers | 40 (29) Mean = 68 years | Thematic analysis |

| Mackenzie 2013 | [45] | Scotland | Both | 12 (5) 50–93 years/7 (7) NR | Hermeneutic phenomenological |

| Martinsen 2015 | [8] | Norway | Survivors | 14 (5) 21–67 years | Framework |

| Reed 2010 | [31] | England | Survivors | 12 (7) NR | Constant comparative methods |

| Saban 2012 | [41] | USA | Caregivers | 46 (46) 18–73 years | Giorgi’s method (phenomenology) |

| Sabari 2000 | [32] | USA | Both | 6 (1) 45–75 years/4 (4) 45–75 years | Constant comparative method |

| Sadler 2014 | [37] | UK | Survivors | 31 (12) 24–62 years | Content analysis |

| Sharma 2012 | [34] | England | Survivors | 9 (4) 37–61 years | Constructivist qualitative approach |

| Simon 2002 | [28] | England | Both | 8 (NR) NR/NR | Framework |

| Ski 2007 | [10] | Australia | Both | 13 (8) 59–84 years/13 (6) 42–81 years | Content analysis |

| Smith 2004 | [6] | Scotland | Caregivers | 90 (65) 19–84 years | Thematic analysis |

| Souter 2014 | [11] | Scotland | Both | 30 (15) 32–86 years/8 (NR) years | Framework |

| Stewart 1998 | [42] | Canada | Caregivers | 20 (20) NR | Inductive method |

| Strudwick 2010 | [33] | England | Caregivers | 9 (8) 30–72 years | Inductive method |

| Talbot 2004 | [40] | Canada | Both | 4 (NR) 71–85 years/5 (NR) 41–69 years | Categorised according to the Handicap Production Process |

| Taule 2015 | [53] | Norway | Survivors | 8 (4) 45–80 years | Interpretative Description* |

| Tholin 2014 | [12] | Sweden | Survivors | 11 (5) 49–90 years | Content analysis |

| Tunney 2014 | [7] | Northern Ireland | Caregivers | 10 (10) NR | Thematic analysis |

| van der Gaag 2005 | [57] | England | Both | 38 (12) 31–81 years/22 (16) 36–81 years | Matrix based method |

| White 2007 | [62] | Canada | Caregivers | 14 (NR) NR | Inductive method |

| White 2009 | [47] | Australia | Survivors | 12 (6) 43–92 years | Inductive method |

| White 2013 | [35] | Australia | Survivors | 9 (2) 53–80 years | Content analysis |

| White 2014 | [46] | Australia | Survivors | 8 (2) 69–88 years | Constant comparative method |

| Wiles 1998 | [48] | England | Both | 9 (10) 50–85 years / 12 (NR) NR | Thematic analysis |

| Wiles 2008 | [36] | England | Survivors | 9 (1) 18–78 years | Thematic analysis |

Note. F: females; NR: Not reported

*Kreuger’s method: descriptive and interpretative analysis of focus groups; Interpretative Description: analysis focused on meaning to generate knowledge of individuals’ experience.

Critical appraisal

All but two studies[26, 66] scored 7 or above on the CASP Qualitative Checklist. None were assessed as being fatally flawed. Main quality limitations pertained to lack of consideration of the relationship between participant and researcher (19 studies), rigour of the data analyses (6 studies), and consideration of ethical issues (4 studies). We identified 7 key papers.[6, 25, 41, 42, 44, 61, 63]

Theoretical standpoints

Few studies specified a theoretical approach. Those which did, either adopted Grounded Theory[43, 48, 55, 64, 66] or phenomenology.[8, 29, 31, 32, 34, 60, 65] A variety of analytical methods were reported (Table 2).

Synthesis of findings

Second order constructs

The first second order construct (continuity of care) included follow-up after hospital discharge[6, 7, 9–12, 27, 47] and facilitation by healthcare professionals.[6, 11, 42, 54, 55] An unaddressed need for continued support was voiced in a quarter of studies.[6–12, 27, 28, 47, 54, 55, 61] Survivors and caregivers felt frustrated and dissatisfied with a lack of proactive follow-up either from primary care,[6, 9, 11, 12, 27] the hospital,[7, 10] or allied healthcare professionals.[47] This led to feelings of dissatisfaction,[8] uncertainty,[8, 10, 47] that a stroke survivor was “forgotten and written off”[25] and that their general practice did not care about them.[12] When regular follow-up was provided, survivors felt supported.[12]

The next second order construct related to access to services. Stroke survivors expected support from community rehabilitation with rehousing, transport, management of psychological and interpersonal difficulties, but these were outside the remit of the services.[37] Although generally appreciated, rehabilitation (PT, OT) was often perceived as insufficient and prematurely withdrawn.[38, 39] Survivors and caregivers felt more progress could have been achieved with longer therapy.[38, 39]

When support from community healthcare services (e.g. SLTs, nurses) was offered either through specifically designed programmes or community organisations targeting survivors with specific needs (dysarthria or aphasia), these were generally appreciated and resulted in feelings of confidence,[45, 57] reassurance,[56] and encouraged positive coping behaviours.[45, 56] Participation in community organisations for people with aphasia gave a sense of belonging, protection and reduced worries.[56]

Emotional support was deemed important but lacking for both survivors and caregivers. Although anxiety and the lack of confidence were common, often survivors did not seek professional help.[27] Having someone with whom to discuss difficulties and who provided motivation was considered valuable to reduce feelings of depression.[8] A sub-group of younger stroke survivors felt disappointed with the lack of vocational support to return to work, contributing to their financial hardship, disappointment,[37] and feelings of loss.[35]

Lack of support for caregivers was reported in 11 studies.[6, 8, 9, 25–29, 38–40] Caregivers felt healthcare professionals assumed that they would provide the majority of care needed[27], with little or no support.[6, 9, 25–27, 29, 38–40] They felt ill prepared and pressured to “become experts” in caring for stroke survivors[27]; causing them anxiety.[39] The need for training was repeatedly emphasised.[6, 9, 25, 38] Caregivers wanted insights into how to cope,[38] how to get organised and establish a routine after discharge.[25] Many also wanted back-up[25, 28, 40] and respite services.[8, 9, 40, 67] Lack of support was highlighted as a barrier to undertaking and/or continuing the caregiving role.[62]

Long waiting times for assessment and rehabilitation,[10, 54] and little or no help from social services[8, 54] left survivors feeling “left in the lurch”.[8] Caregivers felt that access to therapies was not provided early enough.[38, 39] They were frustrated with delays in the initiation of rehabilitation after hospital discharge which caused survivors to “go backwards”.[10] Uncertainty about when therapies would start and how arrangements were made, left them feeling abandoned.[50]

The third second order construct related to information. Unmet information needs and gaps in information provision were highlighted in 41% (n = 21) of the studies.[9–11, 25, 27, 28, 35, 37–39, 41, 43–45, 47–51, 55, 62] Opportunities for support could be missed due to the lack of knowledge of what services were available.[28] The lack of information about local services and how to find them was confusing and prevented access.[10, 25, 28, 62] Many caregivers felt that no information was provided at all.[28] Survivors had to find out information by themselves through the internet, friends and other caregivers.[10] When information was provided, it was often inconsistent and covered only some services.[10] Overcoming this gap in information provision required substantial effort: “I did have to do enormous amount of telephoning.” (caregiver;[25], p. 416). Knowing what help is available, that it can be accessed and telephone contact with a healthcare professional facilitated a caregiving role.[10]

Twelve studies (23%) highlighted insufficient and non-specific information on stroke, its consequences, and recovery.[25, 28, 35, 37–39, 41, 44, 45, 47, 48] Information presented too early after stroke[28] disempowered stroke survivors and caregivers, leading to feelings of confusion, fear[25, 38] and powerlessness.[25] Survivors and caregivers wanted specific information on the significance of post-stroke symptoms (memory loss, swallowing problems, speech, irritability and weight gain) and how to manage them.[48] Lack of information (e.g. on the level of recovery, its trajectory) led to unrealistic expectations of ‘getting back to normal’ given adherence to rehabilitation, leading to disappointment and tensions within a survivor-caregiver dyad.[48] Survivors and caregivers were concerned about medication and wanted to know more about secondary prevention.[11, 27, 49–51]

Eleven studies highlighted aligning information provision to the phase of recovery.[6, 11, 28, 38, 41, 48, 49, 51, 59, 63, 68] Survivors may have limited ability to take in information during the early stages when most information was provided:[49, 51] Caregivers’ information needs increased and diversified with time.[63] More information was needed during preparation for discharge and first few months at home, particularly on long-term rehabilitation goals, secondary prevention, available community services and help navigating the healthcare system.[63] Information on the consequences of stroke (e.g., memory loss, speech difficulties, irritability) was key during post-discharge phase (two months to a year following stroke[48]).

The final second order construct related to quality of communication. Ineffective communication between survivors, caregivers and healthcare services as well as within healthcare services resulted in feelings of frustration[9, 33, 44, 47, 52] and having “to battle the system”.[33] Gaps in the transfer of knowledge within healthcare system[47] and the use of medical jargon sometimes caused confusion[47] and were construed as indifference to survivors’ needs.[52] Insufficient explanations of the therapeutic process during rehabilitation led some survivors to question its efficacy leading to distress and decreased adherence.[47] In contrast, healthcare professionals’ engagement and empathy were valued.[53]

Third order constructs

We developed three third order constructs: (1) perceived marginalisation of stroke survivors and caregivers by the healthcare system, (2) passivity and activity in the relationship between patient/caregiver dyad and the services, (3) change and fluidity of needs after stroke of both patients and caregivers.

Perceived marginalisation results from the limited access to healthcare and health interventions after stroke due to the misalignment between how healthcare access in primary care is organised and survivors’ and caregivers’ competencies. Once back in the community, the responsibility to recognise symptoms and to seek care rests with the patient.[69] Accessing healthcare requires mobilisation of individual resources including knowledge of the condition, ability to communicate effectively with healthcare professionals, and awareness of available services.[69] Cognitive and speech and language problems[70–72] can further affect patient’s ability to negotiate healthcare access. The feelings of disappointment and frustration with limited and/or delayed access[10, 37, 38, 54, 58] and the lack of proactive follow-up from healthcare professionals after stroke[6, 11, 12] reflect patients’ (and caregivers’) responses to perceived marginalisation by the primary care and community healthcare services.

The construct passivity and activity offers a potential solution. It reflects: (1) the tension between passivity of services and the need for proactive service provision to address perceived marginalisation of patients and caregivers by the healthcare system (Fig 3A), and (2) the reciprocity in the healthcare-provider and healthcare-user interactions, where active service provision (e.g. information, follow-up) could encourage active self-management by equipping patients with the necessary tools to better manage the chronic consequences of stroke (Fig 3B). Survivors’[8] and caregivers’[33, 62] active attempts to access information and community services were often met with limited response, including long delays.[62] In one study, the limitations in service provision were construed as barriers set by the healthcare system to ration access.[33] The idea of having to “fight” the (passivity of) the healthcare system[33, 62] can thus be understood as a direct metaphor for perceived marginalisation of stroke survivors and caregivers by the healthcare system. This construct also reflects passivity/activity on the part of the stroke survivor and carer. Perception of marginalisation could stem from lack of support in developing self-management skills. These include: problem solving (e.g. making adjustments in activities of daily living to account for disability), decision making regarding one’s own health (e.g. taking up exercise), finding and utilising resources (e.g. information about condition, recovery and services), forming partnerships with healthcare professionals and taking action (e.g. mastering skills needed to manage the chronic and changing behaviours[73, 74]). Patients and caregivers wanted support with finding and utilising information and relevant healthcare services[62] and looked for guidance from healthcare professionals.[37] Equipping them with these skills could help improve their problem solving and decision making (Fig 3B), especially during the first year when the major adjustment to living with stroke occurs.[75] We posit that the need for active support from services will decrease during the first year after discharge from the hospital as increasing skills and confidence in managing life after stroke will shift the balance towards active patient self-management.

Fig 3. From service passivity and perceived marginalisation to service activity and self-management.

3A: Passive patient-caregiver/ service relationship; 3B: active patient-caregiver / service relationship.

Our final construct, the fluidity and change in (primarily information) needs after stroke emphasises the dynamic aspect of post-stroke recovery. Patients’ needs change with functional improvements (observed earlier in the trajectory) and psychological adaptation to living with stroke.[75] This aspect remained unaddressed by the services. Although information needs diversified and their content changed with time, information provision was not responsive to this change.[6, 11, 51] Caregivers felt that information was not provided at the right time with excess information concentrated in the first few weeks with no follow-up opportunity.[28] The time course of information needs aligns with the need for an ongoing (at least during the first year after stroke) follow-up from a GP.[6, 11, 12]

Discussion

Stroke survivors and their caregivers feel abandoned because they have become marginalised by services and they do not have the knowledge or skills to re-engage. The marginalisation arises because of service passivity and misalignment of information provision with needs, which change with post-stroke recovery. The passivity of services was expressed as lack of continuity of care, including lack of (active) follow-up, limited (in scope and time) and delayed access to community services, as well as inadequate (too little and too general) information about stroke, recovery and healthcare services. We posit that this passivity also has a relational aspect where activating the support from healthcare professionals within the first year after stroke would increase patients’ ability to self-manage their chronic condition. This can be achieved by providing timely and targeted information about stroke, available resources, and by regular follow-ups to foster supporting long-term relationships with healthcare professionals. Active support from health care professionals would be expected to decrease over time as patients and caregivers become more self-reliant and better able to self-manage living with stroke.

We focussed on post-stroke care delivered by primary and community health services after transfer from specialist services. It is likely that the third order construct of fluidity of need is also relevant to specialist care. For example, the importance of matching information provision to patient and caregiver need.

We identified two key areas for potential service focused interventions to address patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions of marginalisation by the healthcare system after the discharge from the hospital and improve capacity for self-management: (1) increasing stroke specific health literacy by targeted and timely information provision, and (2) improving continuity of care and providing better access to community healthcare services.

Information provision and increasing health literacy

In alignment with previous work our synthesis identified deficiencies in information provision on several levels: content, format, and timing.[14] Information regarding stroke and recovery was also a common theme in previous reviews.[13, 76, 77] Although qualitative longitudinal studies on the trajectory of stroke recovery are few,[75, 78–80] the insights from such studies could help target both the timing and the content of information provision.[48, 63]

Health literacy encompasses personal skills, ability and motivation of individuals “(…) to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health”([81], p. 357). Our analyses suggest that patients and caregivers want more information about stroke and secondary prevention, and take active efforts to find information for themselves. Previous reviews have highlighted the interface between information provision and utilisation.[13, 82] Large volumes of sometimes conflicting information from multiple providers can impede understanding. What stroke survivors struggled with in our analyses and those by Gallacher et al.[82] is access to sufficient information and the ability to appraise it. Efforts directed towards helping patients identify sources of trustworthy information which are written in an accessible language and format would help increase stroke specific health literacy,[83] which in turn could support better self-management. Third sector initiatives in a number of countries do aim to provide such resources,[84–87] but our analyses indicate that many stroke survivors are not aware of them.

Continuity of care and support from community services

The lack of continuity of care and its negative consequences for patient care were reported in all previous qualitative reviews which focused on long-term problems,[77] treatment burden,[76] the impact of stroke and its relevance to the development and delivery of services.[13] Three types of continuity can be distinguished: (1) informational (using patient relevant information on stroke and personal circumstances to facilitate appropriate care), (2) management (coherent management of the chronic condition by multiple providers), and (3) relational (an ongoing therapeutic relationship[88]). Unique to our review was a strong emphasis on the lack of follow-up either from a GP, community or specialist services; with patients and caregivers in nine studies (18%) reporting the need for an active follow-up or reassessment to ensure continuity of care.

These two key areas for service interventions could be targeted at the patient, at the carer, or be dyad interventions directed at both patient and carer.[89] We did not review intervention studies in this meta-ethnography. Reviews of evidence of interventions directed at the caregiver and at patient/carer dyads suggest that the former are more effective to improve carer outcome, and the latter to improve patient outcome. [89,90]

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review on the experiences of stroke survivors and caregivers of primary care and community healthcare services with broad coverage of contexts, samples and study focus. By using meta-ethnography we identified patients’ and caregivers’ perceived marginalisation by the passivity of healthcare services. Importantly, we also identified a relational aspect between service activity and patient self-management thus providing a potential solution for how these perceptions could be addressed. We have included studies from a variety of healthcare contexts (Northern America, UK, Australia, Northern Europe, Iran), involving municipal and rural settings, ethnic minorities,[37, 41, 52, 57, 58] and long-term stroke survivors (62% of the studies included survivors at least 1 year after stroke). The substantial degree of convergence of themes across different settings and samples suggests the transferability of these findings.

Our meta-ethnography focused on experiences of a single patient and caregiver population within a more homogenous healthcare context (primary care and community healthcare services) than in previous reviews. The homogeneity of healthcare contexts we studied facilitated meaningful comparisons and translations across studies in relation to post-discharge and long-term experience of care after stroke.[22] Despite methodological variety (Table 2), all studies included specific themes relevant to survivor and/or caregiver experiences of primary care and community healthcare services.

Potential limitations of qualitative research such as limited generalisability and inability to provide firm answers are offset by the consistency of the findings across epistemological traditions, methodologies, countries and healthcare systems. While the included studies achieved good quality scores, many failed to provide sufficient contextual detail. Only a minority included data on stroke severity, specific long-term impairments (e.g. cognitive impairment, physical disability and aphasia), socio-economic status or ethnicity. Most studies employed a cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights on the temporality and intensity of healthcare needs after stroke relative to the trajectory of recovery. Our synthesis was limited to reports in English. However, only 2% of the studies were excluded based on language and studies from non-English speaking countries (in Northern Europe and Iran) were represented. Our review included studies published up until June 2015. Given that we had over fifty studies, it is unlikely that further third order constructs would be identified by extending the review to the present time–i.e it is likely that we achieved data saturation. We are not aware of major changes in the care offered to stroke patients and their carers in primary care in the last couple of years that might have led to new constructs.

Conclusions

Primary care and community health care interventions which focus on improving active follow-up and information provision to patients and caregivers especially in the first year after stroke, could help improve patient self-management, increase stroke specific health literacy and thus mitigate the current perceptions of abandonment felt by many stroke survivors and their caregivers.

Appendix A

PubMed search strategy

Stroke

Stroke (title/abstract)

1 Or 2

stroke[MeSH Terms]

CVA

cerebral stroke

((stroke) OR Stroke[MeSH Terms]) OR CVA) OR cerebral stroke

patients or survivors or family or caregivers or carers

patients[MeSH Terms]

survivors[MeSH Terms]

family[MeSH Terms]

caregivers[MeSH Terms]

carers[MeSH Terms]

(12) OR 13

(9) OR 10

(11) OR 12

((patients or survivors or family or caregivers or carers) OR 15) OR 16

general practice or family practice

private practitioner or general practitioner or family physician or family doctor

community health services

primary health care

homecare services

primary health care[MeSH Terms]

family physician[MeSH Terms]

general practitioner[MeSH Terms]

private practitioner[MeSH Terms]

family doctor[MeSH Terms]

community health services[MeSH Terms]

general practice[MeSH Terms]

family practice[MeSH Terms]

home care services[MeSH Terms]

(((community health services[MeSH Terms]) OR primary health care[MeSH Terms]) OR family physician[MeSH Terms]) AND home care services[MeSH Terms]

(((general practitioner[MeSH Terms]) OR family doctor[MeSH Terms]) OR general practice[MeSH Terms]) OR family practice[MeSH Terms]

18 OR 19 OR 20 OR 21 OR 22

(32) OR 33) OR 34

perspective or experience or opinion or satisfaction or dissatisfaction or needs or demands

patient satisfaction or attitude or needs assessment

patient satisfaction[MeSH Terms]

attitude[MeSH Terms]

needs assessment[MeSH Terms]

(patient satisfaction[MeSH Terms] OR attitude[MeSH Terms]) OR needs assessment[MeSH Terms]

(37) OR 42

((43) AND 35) AND 17) AND 3

qualitative OR focus group OR interviews

qualitative research

qualitative research[MeSH Terms]

evaluation studies as Topic[MeSH Terms]

focus groups[MeSH Terms]

((((((qualitative) OR focus group) OR interviews)) OR qualitative research[MeSH Terms]) OR evaluation studies as Topic[MeSH Terms]) OR focus groups[MeSH Terms]

(44) AND 51

Acknowledgments

Authors are grateful to Dr Robbie Duschinsky for his comments regarding the methodology and conceptualisation of the third order constructs. We are also thankful to Dr Fiona Walter and Dr Ahmed Rashid for their input into the discussion of study findings. We also thank Dr Victoria Hobbs for her help with screening of the titles for the review. We would like to thank Dr Christ McKevitt for facilitating the meeting with stroke survivors from the Stroke Research Patient and Family Group at King’s College and their family members to discuss the findings from this review. We are grateful to all stroke survivors and their family members who provided generous feedback on preliminary findings reported herein.

Data Availability

This is a systematic review of published papers, so our source data are the original publications, all of which are referenced at the end of the paper.

Funding Statement

This qualitative systematic review presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants for Applied Research Programme (Reference Number PTC-RP-PG-0213-20001). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funder had no involvement in the design, conduct, analyses or interpretation of study findings.

References

- 1.Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, Krishnamurthi R, Mensah GA, Connor M, Bennett DA, et al. Global and regional burden of stroke during 1990–2010: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2014;383(9913):245–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24449944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23245604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saka Ö, McGuire A, Wolfe C. Cost of stroke in the United Kingdom. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):27–32. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn281 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 19141506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 Update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38–360. Epub 2015/12/18. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 26673558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deloitte Access Economics. The economic impact of stroke in Australia Deloitte Access Economics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith LN, Lawrence M, Kerr SM, Langhorne P, Lees KR. Informal carers' experience of caring for stroke survivors. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(3):235–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.02983.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 15066101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tunney AM, Ryan A. Listening to carers' views on stroke services. Nurs Older People. 2014;26(1):28–31. doi: 10.7748/nop2014.02.26.1.28.e500 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24471551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinsen R, Kirkevold M, Sveen U. Young and midlife stroke survivors' experiences with the health services and long-term follow-up needs. J Neurosci Nurs. 2015;47(1):27–35. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0000000000000107 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 25565592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Harris R, Fenton W, Cloud G. Perceptions of the role of general practice and practical support measures for carers of stroke survivors: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:57 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-57 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 21699722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ski C, O'Connell B. Stroke: the increasing complexity of carer needs. J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;39(3):172–9. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 17591413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Souter C, Kinnear A, Kinnear M, Mead G. Optimisation of secondary prevention of stroke: a qualitative study of stroke patients' beliefs, concerns and difficulties with their medicines. Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22(6):424–32. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12104 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24606322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tholin H, Forsberg A. Satisfaction with care and rehabilitation among people with stroke, from hospital to community care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28(4):822–9. doi: 10.1111/scs.12116 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24495250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKevitt C, Redfern J, Mold F, Wolfe C. Qualitative studies of stroke—a systematic review. Stroke. 2004;35(6):1499–505. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000127532.64840.36 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 15105517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray J, Ashworth R, Forster A, Young J. Developing a primary care-based stroke service: a review of the qualitative literature. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(487):137–42. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12817361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D, Walter F, Feder G, Ridd M, et al. “Medication career” or “Moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta-ethnography of patients' experience of antidepressants. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(1):154–68. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.068 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 19013702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aziz NA, Pindus DM, Mullis R, Walter FM, Mant J. Understanding stroke survivors’ and informal carers’ experiences of and need for primary care and community health services—a systematic review of the qualitative literature: protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):6:e009244. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009244 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 26739728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2011 Edition. South Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foot C, Sonola L, Bennett L, Fitzsimons B, Raleigh V, Gregory S. Managing quality in community health care services London: The King's Fund; 2014. December 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Research Checklist Oxford, UK: CASP; 2013. [cited 2015 28 August]. Available from: http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_29c5b002d99342f788c6ac670e49f274.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dixon-Woods M, Sutton A, Shaw R, Miller T, Smith J, Young B, et al. Appraising qualitative research for inclusion in systematic reviews: a quantitative and qualitative comparison of three methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2007;12(1):42–7. doi: 10.1258/135581907779497486 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 17244397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noblit GW, Hare RW. Meta-ethnography: Synthesising qualitative studies Qualitative Research Method. 11 London: SAGE Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Britten N, Campbell R, Pope C, Donovan J, Morgan M, Pill R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):209–15. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finfgeld DL. Metasynthesis: the state of the art—so far. Qual Health Res. 2003;13(7):893–904. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253462 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 14502956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennion AE, Shaw RL, Gibson JM. What do we know about the experience of age related macular degeneration? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(6):976–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.023 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22709445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Denman A. Determining the needs of spouses caring for aphasic partners. Disabil Rehabil. 1998;20(11):411–23. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 9846241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant JS. Home care problems experienced by stroke survivors and their family caregivers. Home Healthc Nurse. 1996;14(11):892–902. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 9060288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hare R, Rogers H, Lester H, McManus R, Mant J. What do stroke patients and their carers want from community services? Fam Pract. 2006;23(1):131–6. Epub 2005/11/26. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi098 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 16308328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simon C, Kumar S. Stroke patients' carers' views of formal community support. Br J Community Nurs. 2002;7(3):158–63. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2002.7.3.10216 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 11904553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El Masry Y, Mullan B, Hackett M. Psychosocial experiences and needs of Australian caregivers of people with stroke: prognosis messages, caregiver resilience, and relationships. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2013;20(4):356–68. doi: 10.1310/tsr2004-356 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23893835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low JTS, Roderick P, Payne S. An exploration looking at the impact of domiciliary and day hospital delivery of stroke rehabilitation on informal carers. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(7):776–84. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr748oa ; PubMed Central PMCID: 15573834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed M, Harrington R, Duggan A, Wood VA. Meeting stroke survivors' perceived needs: a qualitative study of a community-based exercise and education scheme. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(1):16–25. doi: 10.1177/0269215509347433 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 20026574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabari JS, Meisler J, Silver E. Reflections upon rehabilitation by members of a community based stroke club. Disabil Rehabil. 2000;22(7):330–6. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 10877487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strudwick A, Morris R. A qualitative study exploring the experiences of African-Caribbean informal stroke carers in the UK. Clin Rehabil. 2010;24(2):159–67. doi: 10.1177/0269215509343847 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 20103577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharma H, Bulley C, van Wijck FMJ. Experiences of an exercise referral scheme from the perspective of people with chronic stroke: a qualitative study. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(4):336–43. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2011.05.004 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23122441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White JH, Bynon BL, Marquez J, Sweetapple A, Pollack M. 'Masterstroke: a pilot group stroke prevention program for community dwelling stroke survivors'. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(11):931–8. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.717578 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23641954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiles R, Demain S, Robison J, Kileff J, Ellis-Hill C, McPherson K. Exercise on prescription schemes for stroke patients post-discharge from physiotherapy. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(26):1966–75. doi: 10.1080/09638280701772997 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 18608413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadler E, Daniel K, Wolfe CDA, McKevitt C. Navigating stroke care: the experiences of younger stroke survivors. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(22):1911–7. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2014.882416 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24467678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cecil R, Parahoo K, Thompson K, McCaughan E, Power M, Campbell Y. 'The hard work starts now': a glimpse into the lives of carers of community-dwelling stroke survivors. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20(11–12):1723–30. Epub 2010/09/08. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03400.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 20815862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cecil R, Thompson K, Parahoo K, McCaughan E. Towards an understanding of the lives of families affected by stroke: a qualitative study of home carers. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(8):1761–70. doi: 10.1111/jan.12037 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23215761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot LR, Viscogliosi C, Desrosiers J, Vincent C, Rousseau J, Robichaud L. Identification of rehabilitation needs after a stroke: an exploratory study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:53 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-53 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 15383147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saban KL, Hogan NS. Female caregivers of stroke survivors: coping and adapting to a life that once was. J Neurosci Nurs. 2012;44(1):2–14. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e31823ae4f9 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22210299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart MJ, Doble S, Hart G, Langille L, MacPherson K. Peer visitor support for family caregivers of seniors with stroke. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(2):87–117. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 9807290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dalvandi A, Heikkilä K, Maddah SSB, Khankeh HR, Ekman SL. Life experiences after stroke among Iranian stroke survivors. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57(2):247–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00786.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 20579161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Donnellan C, Martins A, Conlon A, Coughlan T, O'Neill D, Collins DR. Mapping patients' experiences after stroke onto a patient-focused intervention framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(6):483–91. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.702844 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22889261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackenzie C, Kelly S, Paton G, Brady M, Muir M. The Living with Dysarthria group for post-stroke dysarthria: the participant voice. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2013;48(4):402–20. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12017 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23889836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White JH, Patterson K, Jordan L- A, Magin P, Attia J, Sturm JW. The experience of urinary incontinence in stroke survivors: a follow-up qualitative study. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81(2):124–34. doi: 10.1177/0008417414527257 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 25004588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.White JH, Magin P, Pollack MR. Stroke patients' experience with the Australian health system: a qualitative study. Can J Occup Ther. 2009;76(2):81–9. Epub 2009/05/22. doi: 10.1177/000841740907600205 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 19456086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wiles R, Pain H, Buckland S, McLellan L. Providing appropriate information to patients and carers following a stroke. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(4):794–801. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00709.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 9829668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allison R, Evans PH, Kilbride C, Campbell JL. Secondary prevention of stroke: using the experiences of patients and carers to inform the development of an educational resource. Fam Pract. 2008;25(5):355–61. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmn048 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 18753289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones SP, Auton MF, Burton CR, Watkins CL. Engaging service users in the development of stroke services: an action research study. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(10):1270–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02259.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 18416779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lawrence M, Kerr S, Watson H, Paton G, Ellis G. An exploration of lifestyle beliefs and lifestyle behaviour following stroke: findings from a focus group study of patients and family members. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:97 doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-97 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 21143874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blixen C, Perzynski A, Cage J, Smyth K, Moore S, Sila C, et al. Stroke recovery and prevention barriers among young African-American men: potential avenues to reduce health disparities. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21(5):432–42. doi: 10.1310/tsr2105-432 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 25341388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taule T, Strand LI, Skouen JS, Råheim M. Striving for a life worth living: stroke survivors' experiences of home rehabilitation. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(4):651–61. doi: 10.1111/scs.12193 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 25648326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hart E. The use of pluralistic evaluation to explore people's experiences of stroke services in the community. Health Soc Care Community. 1999;7(4):248–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.1999.00183.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 11560640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lilley SA, Lincoln NB, Francis VM. A qualitative study of stroke patients' and carers' perceptions of the stroke family support organizer service. Clin Rehabil. 2003;17(5):540–7. doi: 10.1191/0269215503cr647oa ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12952161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorze GL, Salois-Bellerose É, Alepins M, Croteau C, Hallé M-C. A description of the personal and environmental determinants of participation several years post-stroke according to the views of people who have aphasia. Aphasiology. 2014;28(4):421–39. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2013.869305 [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Gaag A, Smith L, Davis S, Moss B, Cornelius V, Laing S, et al. Therapy and support services for people with long-term stroke and aphasia and their relatives: a six-month follow-up study. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19(4):372–80. doi: 10.1191/0269215505cr785oa ; PubMed Central PMCID: 15929505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eaves YD. Rural African American caregivers' and stroke survivors' satisfaction with health care. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2002;17(3):72–84. doi: 10.1097/00013614-200203000-00007 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Law J, Huby G, Irving A-M, Pringle A-M, Conochie D, Haworth C, et al. Reconciling the perspective of practitioner and service user: findings from The Aphasia in Scotland study. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2010;45(5):551–60. doi: 10.3109/13682820903308509 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 19886848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brunborg B, Ytrehus S. Sense of well-being 10 years after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(7–8):1055–63. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12324 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24004444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Danzl MM, Hunter EG, Campbell S, Sylvia V, Kuperstein J, Maddy K, et al. "Living with a ball and chain": the experience of stroke for individuals and their caregivers in rural Appalachian Kentucky. J Rural Health. 2013;29(4):368–82. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12023 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 24088211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White CL, Korner-Bitensky N, Rodrigue N, Rosmus C, Sourial R, Lambert S, et al. Barriers and facilitators to caring for individuals with stroke in the community: the family's experience. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2007;29(2):5–12. Epub 2008/02/05. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 18240626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, Gignac MA. Stroke family caregivers' support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(4):315–24. Epub 2012/06/13. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.691937 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22686259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barnsley L, McCluskey A, Middleton S. What people say about travelling outdoors after their stroke: a qualitative study. Aust Occup Ther J. 2012;59(1):71–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00935.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22272885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brown K, Worrall L, Davidson B, Howe T. Living successfully with aphasia: family members share their views. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2011;18(5):536–48. doi: 10.1310/tsr1805-536 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22082703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burman ME. Family caregiver expectations and management of the stroke trajectory. Rehabil Nurs. 2001;26(3):94–9. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2001.tb02212.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12035695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gosman-Hedstrom G, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. 'Mastering an unpredictable everyday life after stroke'- older women's experiences of caring and living with their partners. Scand J Caring Sci. 2012;26(3):587–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.00975.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22332755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Graven C, Sansonetti D, Moloczij N, Cadilhac D, Joubert L. Stroke survivor and carer perspectives of the concept of recovery: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35(7):578–85. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.703755 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 22889405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35 PubMed Central PMCID: 16872487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leys D, Hénon H, Mackowiak-Cordoliani M-A, Pasquier F. Poststroke dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):752–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70221-0 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 16239182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolfe CD, Crichton SL, Heuschmann PU, McKevitt CJ, Toschke AM, Grieve AP, et al. Estimates of outcomes up to ten years after stroke: analysis from the prospective South London Stroke Register. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):e1001033 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001033 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 21610863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engelter ST, Gostynski M, Papa S, Frei M, Born C, Ajdacic-Gross V, et al. Epidemiology of aphasia attributable to first ischemic stroke: incidence, severity, fluency, etiology, and thrombolysis. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1379–84. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221815.64093.8c ; PubMed Central PMCID: 16690899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2601_01 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12867348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Corbin J, Strauss A. Unending work and care: managing chronic illness at home San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kirkevold M. The unfolding illness trajectory of stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24(17):887–98. doi: 10.1080/09638280210142239 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12519484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gallacher K, Morrison D, Jani B, Macdonald S, May R, Montori M, et al. Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23824703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Murray J, Ashworth R, Forster A, Young J. Developing a primary care-based stroke service: a review of the qualitative literature. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(487):137–42. ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12817361. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burton CR. Re-thinking stroke rehabilitation: the Corbin and Strauss chronic illness trajectory framework. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(3):595–602. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01517.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 11012801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Burman ME. Family caregiver expectations and management of the stroke trajectory. Rehabil Nurs. 2001;26(3):94–9. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2001.tb02212.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 12035695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eilertsen G, Kirkevold M, Bjørk IT. Recovering from a stroke: a longitudinal, qualitative study of older Norwegian women. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(13–14):2004–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03138.x ; PubMed Central PMCID: 20920026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nutbeam D. Health Promotion Glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998;13(4):349–64. doi: 10.1093/heapro/13.4.349 PubMed PMID: 10318625; PubMed Central PMCID: 10318625. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gallacher K, Morrison D, Jani B, Macdonald S, May CR, Montori VM, et al. Uncovering treatment burden as a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2013;10(6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001473 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23824703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Osborne RH, Batterham RW, Elsworth GR, Hawkins M, Buchbinder R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1–17. Epub Jul 16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-658 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 23855504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Adams R, Acker J, Alberts M, Andrews L, Atkinson R, Fenelon K, et al. Recommendations for improving the quality of care through stroke centers and systems: an examination of stroke center identification options: multidisciplinary consensus recommendations from the Advisory Working Group on Stroke Center Identification Options of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2002;33(1):e1–7. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101262 ; PubMed Central PMCID: 11779938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stroke Association. Stroke: A carer’s guide. London: 2012.