Abstract

Objective

Women experience a variety of changes at midlife that may affect sexual function. Qualitative research approaches can allow a deeper understanding of women’s experiences. We conducted 20 individual interviews and 3 focus groups among sexually active women aged 45–60 (total N=39) to explore how sexual function changes during midlife.

Methods

Interviews and focus groups were conducted by a trained facilitator using a semi-structured guide. All data were audio recorded and transcribed. Two investigators used a subsample of data to iteratively develop a codebook. The primary investigator coded all data. A second investigator coded a randomly selected 25% of interviews. Codes regarding changes in sexual function were examined and key themes emerged.

Results

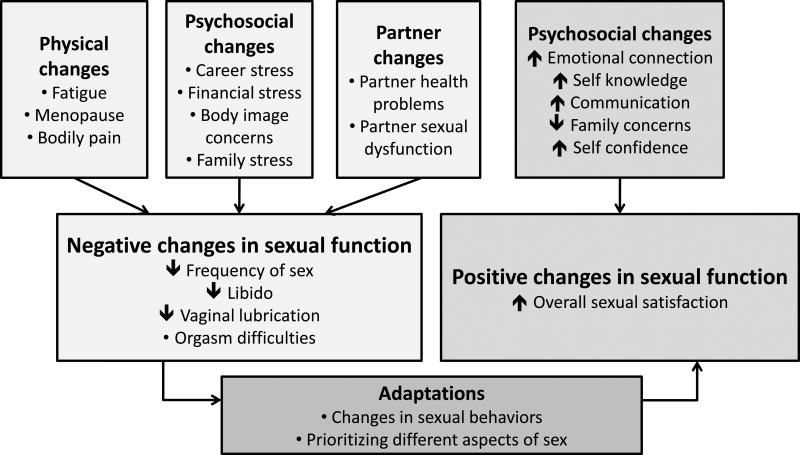

The mean age was 52, and most women were peri-or postmenopausal. Fifty-four percent of women were white, 36% black, and 10% of another race. Participants discussed positive and negative changes in sexual function. The most common negative changes were decreased frequency of sex, low libido, vaginal dryness, and anorgasmia. Participants attributed negative changes to menopause, partner issues, and stress. Most participants responded to negative changes with adaptation, including changing sexual behavior and prioritizing different aspects of sex. Participants also reported positive changes, attributed to higher self-confidence, increased self-knowledge, and better communication skills with aging.

Conclusions

In this qualitative study, women described experiencing both positive and negative changes in sexual function during midlife. When negative changes occurred, women often adapted behaviorally and psychologically. Providers should recognize that each woman’s experience is unique and nuanced and provide tailored care regarding sexual function at midlife.

Keywords: menopause, sexual function, sexual dysfunction, aging

INTRODUCTION

Sexual function is an important aspect of quality of life for many women1–4. Midlife (approximately age 40–60) is a time of many changes that may impact sexual function, including physical changes (e.g., menopausal symptoms, medical conditions), psychological changes (e.g., disrupted sleep, mood symptoms), sociocultural changes (e.g., cultural expectations regarding older women’s sexuality), and interpersonal changes (e.g., loss of a sexual partner, development of sexual dysfunction in one’s sexual partner)5–7.

Longitudinal studies indicate that sexual function declines during midlife, particularly during the menopausal transition. Most negative changes are in the domains of sexual desire, arousal, and vaginal dryness/sexual pain8–11. However, longitudinal studies may fail to capture nuances and individual variations in women’s experiences. These studies typically use multiple-choice questions to assess sexual function—the investigator chooses the topics, domains, wording of the question, and the answers. This allows for standardization of instruments across women and ease of administration with large samples. However, describing changes in sexual function using summary scores, means, and percentages may miss nuances and individual variations in women’s experiences.

By using open-ended questions and allowing participants to speak at length, a qualitative approach lets participants use their own words to describe their experiences and allows them to discuss the facets of the subject most important to their own experience. Researchers may then uncover concepts that they never realized existed, and the themes most relevant to the participants arise naturally. In this study, we sought to use a qualitative approach to better understand midlife women’s lived experiences of changes in sexual function with aging.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study sample

Study participants were recruited from the general population of Pittsburgh, PA using flyers, research registries, electronic newsletters, and Internet postings. Women who responded were screened for eligibility over the telephone after giving verbal assent. Women were eligible if they were aged 45–60 and had been sexually active with a partner at least once in the prior 12 months. We included this age group in order to focus on midlife women. We excluded women who had not been sexually active in the prior 12 months because we were interested in women’s relatively recent experiences of their sexual function. Women who had not been recently sexually active would be discussing more remote experiences. Women were given the option to participate in either an individual interview or a focus group.

Individual Interview and Focus Group Conduct

Face-to-face interviews and focus groups were led in a private room by a facilitator with extensive experience in qualitative research methods and sexual anthropology (M.H.) and were conducted between December 2014 and May 2015. Interviews and focus groups both lasted approximately 60 minutes. An introductory script encompassing the purpose of the study and all elements of informed consent, including the voluntary nature of the study and the ability to discontinue the study at any time, was read to participants at the start of each session. Women were then given the option to continue with the study or leave. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approved this study and recommended this informed consent process over written informed consent. We chose to use both focus groups and interviews; the former may uncover new themes due to group synergy, and the latter allow us to hear the perspectives of women who do not wish to discuss sexuality in a group context.

Interviews and focus groups were guided by an semi-structured guide; however, consistent with the emergent nature of qualitative research, participants may have been asked different or additional questions not in the guide, depending on her responses (see supplementary materials). The guide was developed by the principal investigator (H.N.T.) along with a stakeholder advisory board of midlife women and healthcare providers for midlife women.

Each session was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participant names, and names of any individuals they mentioned, were not transcribed. A random 10% section of each interview and focus group was reviewed for accuracy of transcription. The principal investigator served as a note taker for each focus group but did not participate in discussions. Minimal notes were taken as needed by the facilitator during individual interviews. Each interview and focus group participant also completed a demographic questionnaire, and transcriptions were linked to questionnaires using a study identification number.

Sample size in qualitative research is guided by the concept of thematic saturation, which means no new information or themes are uncovered in the course of ongoing interviews and focus groups. Thematic saturation was achieved in this study. As the goal in qualitative research is more focused on understanding a phenomenon in-depth as opposed to hypothesis testing or generalizability, sample sizes tend to be smaller than in quantitative research. Our sample size is consistent with general qualitative research norms12–14.

Analysis

Data analysis proceeded using a thematic analysis approach using a fine-grained editing style in which the coder searches for “meaningful units or segments” of text which are coded and categorized15. The principal investigator read all transcripts and then met with the facilitator, who conducted all interviews and focus groups, to develop a draft codebook. Codebook development proceeded in an iterative process, with investigators reading and coding two randomly selected interviews then meeting to review agreement, until a final codebook was agreed upon. Atlas.ti software was used to assist with coding (Scientific Software Development, Berlin). The primary investigator then coded all data using this final codebook. The facilitator coded five randomly selected interviews and Cohen’s kappa statistics were calculated to assess inter-coder reliability. Kappa score was 0.84 indicating excellent inter-coder agreement. Codes relating changes in sexual function over time were examined and key themes emerged (Figure). Representative quotations were selected form the transcripts to illustrate these key themes.

Figure.

Changes in women’s sexual function during midlife

RESULTS

Demographics and summary of themes

The characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. All but two participants reported their sexual orientation as heterosexual; one woman reported her orientation as homosexual and one marked both heterosexual and not sure. The themes discussed are summarized in the Figure. Participants described experiencing both negative and positive changes in sexual function with aging, sometimes both within the same individual. Participants highlighted the changes they experienced, what they felt were the likely causes for these changes, and how they adapted to these changes.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Individual interviews (N=20) |

Focus groups (3 groups, total N=19) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (range) | 52.3 (45–58) | 53.4 (46–59) |

| Married or cohabitating, N(%) | 12(60) | 11 (61)* |

| Race / ethnicity, N(%) | ||

| White | 8 (40) | 13 (68) |

| Black | 9 (45) | 5 (26) |

| Other | 3 (15) | 1 (5) |

| College degree or higher education status, N(%) | 9 (45) | 12 (63) |

| Self-reported menopausal status, N(%) | ||

| Premenopausal | 3 (15) | 2 (10) |

| Perimenopausal | 9 (45) | 8 (42) |

| Postmenopausal | 4 (20) | 7 (36) |

| Not sure | 4 (20) | 2 (10) |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 20 (100) | 17 (89) |

| Homosexual | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Bisexual | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Not sure | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

One woman did not answer the martial status question

Negative changes in sexual function

Types of negative changes

The most common negative changes were decreased frequency of sex, low libido, vaginal dryness, and orgasm difficulties (Table 2). We considered decreased frequency of sex as a negative change, as most women in this study expressed frustration and disappointment with this change. However, it should be noted that a small subset of women had noted decreased frequency in sex, but were not bothered by it. Some participants noted these sexual problems could be interrelated. For example, one 53-year-old woman explained how she had difficulty reaching orgasm, and as a result, her desire for and receptiveness to sexual activity eventually waned. She expressed, “While I’m participating, I’m also feeling like, ‘Oh, why bother? It’s not going to be as good. It’s going to be much harder to do. This isn’t going to happen for me.’” For this woman, an issue with reaching orgasm eventually became accompanied by an issue with libido.

Table 2.

Frequently discussed negative changes in sexual function among midlife women

| Decreased frequency of sex | Interviewer: And so how often do you feel the desire for sex? Woman: Maybe a couple times a week now… So it’s not like it used to be 20-something years ago, like we had to be at it constantly. [laughs] Interviewer: I was just going to ask if it changed at all as you’d aged. Woman: Yes, yes, most definitely has. (58-year-old woman) |

| Low libido | [There is] definitely a difference for me pre-menopausal and peri-menopausal… It takes me a lot longer to talk myself into wanting to have sex. And if he initiates it, I have to think harder like, “Do I really want to do this? [laughs] Or do I really want to go to sleep? Or do I really have something else I’d rather do?” So very, very different, and I don’t like it. (53-year-old woman) |

| Vaginal dryness | Because my problem just came about in the last year or two when I really started noticing the dryness down there, and he thought that I just didn’t want to have sex. I said, “It’s not that I don’t want to have sex. It hurts!”… I had to explain to him that the tissues down there, my hormones were changing… (55-year-old woman) |

| Orgasm difficulties | I don’t climax nearly as often and when I do, I have to work much, much harder at it… Whereas before menopause, I would say I probably reached orgasm probably 75% of the time… Now, it’s 25%, certainly a big change… My orgasms are not as intense as they used to be… It’s like everything has gotten diluted as I’ve gotten older… it’s just like someone poured water on it and it’s just not as good, it doesn’t taste as good, doesn’t feel as good, doesn’t work as well… Oh, [if] I could go back to the sex I was having when I was 40 or 41. [laughs] Oh, it was awesome. (53-year-old woman) |

Reasons for negative changes

There were some women who specifically related negative changes to physical issues, particularly menopause and bodily pain. Some women noted an abrupt change in sexual function, especially libido, with menopause. However, many other participants attributed negative changes to psychosocial issues, such as stress, family and work obligations, and changes in body image (Table 3). Many felt that they were busier and under more stress than when they were younger; they felt their multiple different social roles, as wife, daughter, mother, and worker, made it difficult for them to relax and enjoy sex. When asked what leads to unsatisfying sex, one woman said, “When our lives are busy and our heads are not all in it, which happens a lot to me because I’m doing a million different things. And if you’re not completely in it, then you just are going through the motions, because you’re thinking of your to-do list or whatever” (48-year-old woman). One woman felt that women are more sexually susceptible to stress than men: “But I always think it’s psychological with us, with women. I mean, we just have so much going on, we wear so many hats. Guys can just turn it off and be like ‘OK. Yeah, I’m ready, come on, let’s go.’ Where us, we’re very emotional, so there’s so many things, triggers that we have to turn stuff off” (48-year-old woman).

Table 3.

Reasons for negative changes in sexual function with aging

| Physical issues | |

|

| |

| Fatigue | A lot of times we’re both in bed at 9 o’clock, we’re so exhausted, you know. And I think we’re getting older. (55-year-old woman) |

|

| |

| Menopause | Oh yeah, menopause is a bitch. [laughs] It’s awful… the whole thing with the clitoris… it just takes a lot more stimulation to get there. (56-year-old woman) |

| [U]ntil you hit menopause, I don’t think you really realize what you’re facing when you cross over that bridge and you kind of always assume that your sex is going to be good… and then it changes and you’re like, “Really? This is what I’m stuck with for the rest of my life?” (53-year-old woman) | |

|

| |

| Bodily pain | Oh God, I’m getting old, and my knee was bothering me [during sex]. And I’m top – and my knee’s bent, like “Oh, my knees.” It was just awful experience. [laughs]… And I’m like, “I can’t do this.” I’m not as flexible as I was before. (51-year-old woman) |

|

| |

| Psychosocial issues | |

|

| |

| Financial stress | Interviewer: So when did [sex] start declining? 57-year-old woman: When life showed up, you know, bills, jobs, stress, you know what I mean?… like if I’m worried about a bill, “Get out of here. No! You ain’t getting any.” |

|

| |

| Body image concerns | [T]his is another cruel joke in life. Once you get over menopause, your breasts change. They are not as perky, firm, and when you lay down, [laughter] you try to get them to conform the way they’re supposed to… It bothers me tremendously that that also has changed. (56-year-old woman, focus group 2) |

|

| |

| Family-related issues | Our [adult] son was staying with us for a while… And [my partner] wanted to have sex and I go, “No way! [Son’s name] is over there, right next door, he can hear us.” … I just couldn’t get comfortable with having sex and he’s in the next room. (47-year-old woman) |

|

| |

| Partner issues | |

|

| |

| Partner health issues | Yeah, I like to have sex all the time but I can’t have it with him… He’s six years older than me, but he has a lot of medical problems with him. He has things wrong with his back and his shoulders and I don’t have time for all that. You know, I sometimes need to find me somebody else. (50-year-old) |

|

| |

| Partner sexual function | I’ve been married 35 years to my husband… and we had a very long [laughs] young sex life… My husband developed prostate cancer. And he had to have his prostate removed. And the doctor did not tell him that there was a chance that he would not perform the same way… So let’s put it this way: he has to use Cialis. It really does kind of put a damper on… that side of it… I know he gets bummed because he never had any trouble, you know? (56-year-old woman) |

| I think my spouse, he’s lost the desire, and he’s been going through a lot of stress so it’s been kind of hit or miss. Depression… so he’s not really that interested anymore where I’m at that age where I’m like, you know, “let’s go!” (48-year-old woman, focus group 2) | |

Partner issues, including relationship discord, partner health problems, and partner sexual dysfunction, were also cited as a cause of negative changes in sexual function (table 3). Several participants discussed how physical and mental health issues, such as depression, prostate cancer, or diabetes had led to erectile dysfunction or low libido in their partners, which had an overall negative effect on the woman’s sexual satisfaction. Some participants also mentioned that their partners faced some of the same challenges they did – being too busy, tired, or stressed for sex.

Response to negative changes

Most participants responded to negative changes with adaptation, including changing sexual behavior and prioritizing different aspects of sex (Table 4). Changes in sexual behavior included lengthening foreplay, trying different sexual positions or different types of sexual activity, and using sexual aids such as vibrators or lubricants. Many of these changes in sexual behavior were in response to difficulties with vaginal dryness or sexual pain. Several participants had tried lubricants but were disappointed in them; they noted they “ruined the mood” or didn’t last long enough, and some had concerns about whether these products were safe. Some noted that receiving oral sex helped with lubrication difficulties. With regards prioritizing different aspects of sex, participants discussed how, as they got older, they placed more importance on feeling connected and intimate with their partner than the physical aspects of sex, such as reaching orgasm.

Table 4.

How midlife women adapt to negative changes in sexual function

| Changes in sexual behavior | We use lubricants more. He just recognizes foreplay is just going to take longer. I have to direct him a little bit better because it just doesn’t come as easily to me… The positions that I used to have better sexual response in don’t work for me and I’ve just had to be more creative as I’ve gotten older. (53-year-old woman) |

| 55-year-old woman: At this point in my life, oral [sex] is beneficial because I’m not as lubricated as I was even 10 years ago. (Focus group 1) | |

|

| |

| Prioritizing other aspects of sex | Making sure that we’re intimate and communicating and even if we’re not in the mood to still, there’s other ways to be intimate. You don’t have to necessarily be having sexual intercourse to be being sexually active… it’s just being intimate in your conversation and you’re holding hands and just taking that time… (48-year-old woman) |

| It matters more that we love each other and care about each other. And if the sex is not always as wonderful as it used to be, nobody’s that upset. It’s not that big of a deal. (55-year-old woman) | |

Positive changes in sexual function

While discussion of negative changes in sexual function was common, a number of participants also discussed positive changes with aging. For some, sex was actually more frequent than when they were younger. In contrast, some women noted that the frequency of sex had decreased, but they still felt that overall they were just as satisfied or even more satisfied with sex than when they were younger.

Participants gave a number of reasons for experiencing positive changes in sexual function with aging (Table 5). They discussed that they felt more comfortable in their own skin than when they were younger, and this led them to more freely express themselves in the bedroom. They also felt that as they got older, they had a better understanding of their own bodies and sexual needs, and also felt more empowered to communicate their sexual needs to their partners. Additionally, some discussed how as family-related concerns (e.g., caring for young children or the fear of getting pregnant) decreased with aging, sex because more pleasurable. Finally, some discussed how over the course of a years-long relationship, two people can develop a deep and intimate connection, as well as a deep understanding of one another’s sexual needs, that makes sex more fulfilling over time.

Table 5.

Reasons for positive changes in sexual function

| Stronger emotional connection | “Because I was younger – I had boyfriends and it was hormonal… As you get older, your feelings change. And you care more about the person… Because you actually love this person… so when you make love, [there’s] just more substance to it… (51-year-old woman) |

|

| |

| Better ability to understand and communicate sexual needs | [O]ver the time, you learn with that partner, so the longer you’re with that partner, you learn what they like, they learn what you like, so it’s not like having to teach the kid how to ride the bike every time they get on. (46-year-old woman, focus group 3) |

| I couldn’t communicate what I wanted when I first started having sex… I just couldn’t guide him on what would feel right or what would feel good. It just seemed like he should know… Eventually I think I felt more confident as a person and just being able to communicate better in general. I think part of it was maturity… (58-year-old woman) | |

| [Until recently] I’ve never had a mate… help me get to know my body. A lot of times, we just go in and expect them to know what to do… so I’ve found myself talking during intercourse and say, “OK, touch me here”… Or saying “No, that ain’t working, let’s try something else.”… so it’s important to me now as a 48 year-old woman… I just feel more free and able to communicate and I know my body now ‘cause I really didn’t know my body, even at 27, I really didn’t know myself… It was different then because it was just about the getting the guy off… As opposed to now, I’m getting gratified and my partner’s gratified. (48-year-old woman) | |

|

| |

| Decreased family concerns | I find that as I get older… I get an orgasm a lot faster – I went through menopause and I think a lot of times when I was younger that fear of getting pregnant… And now that I don’t have to worry about it anymore, I just… find that it’s sort of easier to have a climax than it was… (58-year-old woman, focus group 1) |

| Because my kids are both now going to college… now that they’re gone… there’s a whole new freedom I have. This is the first time in 20 years that I’ve not had children in my house… Yeah, I have a whole new sense of freedom about myself. That I can have fun in any way. (48-year-old woman) | |

|

| |

| More self confidence | 57-year-old woman: For me [sex] really, really is intense. I had to have a hysterectomy in my 30’s… after that, I think I became extremely uninhibited and I dated an older gentleman… and our sex is intense. Every time it gets better. I think as you get older, for me, it was I’d say more of a comfort level… Just being more comfortable with yourself. |

| 46-year-old woman: Yeah, I think I would have to agree with her… now as I’m getting older in age, sex for me is more intense. I feel like when I was younger, I just wasn’t comfortable with myself… And so as I’m getting older, even though I’ve just worked through a few different men, I feel like I have a little bit more confidence about it… and it allows me to be a little more free with the whole experience. | |

| 57-year-old woman: I think for me, the physical feeling is probably less intense than when I was young, but the emotional piece of it is much better. I can feel more playful, I can be less inhibited, I’m more comfortable with my body. I’m able to express myself better and accept his expression better. So even physically, although it’s not like fantastic as it was, there’s other pieces that compensate to make it better. I’d rather be here than there… (Focus group 2) | |

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative study of sexually active women aged 45–60, we found that participants experienced both negative and positive changes in sexual function as they aged. They attributed negative changes to physical issues, such as menopause, and psychosocial issues, such as life stressors. Many adapted to negative changes, by either changing their sexual behavior or by prioritizing different aspects of sex. Women who experienced positive changes attributed them to increased self-confidence, better self-knowledge, and improved communication skills.

While most prior longitudinal studies have documented negative changes in sexual function as women move through midlife9–11,16, fewer studies have highlighted positive changes. Two literature reviews regarding sexual function and aging in women concluded that many studies have shown relative stability in sexual function over time5,17. The review by Dr. Hayes and Dr. Dennerstein also noted that in many studies, a small (approximately 5–15%) proportion of women showed improvement in sexual function over time. They noted that this could be a real observed effect, or a result of regression to the mean or a survivor effect17. These findings echo the women in our study – some women experience negative changes, but others can experience positive changes. Studies that only look at the population’s mean sexual function over time may miss these nuances and differences.

Notably, some women reported both negative and positive changes. Many of the negative changes participants described focused on more physically oriented aspects of sexual function, such as lubrication or ability to achieve orgasm, while positive changes were more likely to involve improvement in feelings of intimacy or overall sexual satisfaction.

While some women attributed negative changes in sexual function to physical issues, particularly menopause, more women attributed negative changes to psychosocial issues. Because the prevalence of female sexual dysfunction appears to peak at midlife18, much of the prior research on changes in sexual function has focused on the role of menopause and hormones. However, our study highlights the importance of considering psychosocial factors as well. Longitudinal quantitative studies have likewise demonstrated a link between psychosocial factors (including increased stress19,20, mood symptoms10,11,16,20, childcare burden10, and partner issues9,16) and worsening sexual function.

Several women in this study noted that erectile dysfunction in male partners had a negative impact on their own sexual function. Women reported that they themselves required longer and more intense stimulation to achieve orgasm than when they were younger; if their partner concurrently developed erectile dysfunction, he might have difficulty providing this long, intense stimulation, especially if the couple focuses on penetrative intercourse. Erectile dysfunction has been correlated with lower sexual function scores in female partners previously21. Some women in our study expressed frustration and disappointment with erectile dysfunction in male partners. However, other women took action, by encouraging their partners to take pharmaceutical treatments or asking their partners to try different types of sexual activity, such as oral sex.

We found that while the experience of physical changes in sexual function, such as lubrication difficulties, was common in this study, many women found ways to adapt to these physical changes in order to maintain overall sexual satisfaction. These adaptations sometimes required women speaking up and taking action with regards to sexual behavior, such as suggesting lubricant or vibrator use, or trying different sexual activities or positions. But women also discussed changing their priorities around sex; as they aged, they de-emphasized physical sexual satisfaction and placed more importance on emotional satisfaction. Prior work by Sandra Leiblum has likewise found that women are often able to maintain sexual satisfaction throughout the midlife transition by “alterations in the sexual script.”22 These findings resonate with newer models of female sexual response, which highlight that both physical and emotional satisfaction are important outcomes of sex23.

Women who experienced positive changes attributed them to several factors, most notably increased self-acceptance, self-knowledge, and self-confidence. While many women discussed changes in their bodies with aging, such as gaining weight or sagging breasts, not all were self-conscious about these changes. Some women reported higher self-acceptance and body positivity over time, despite physical changes that would typically be labeled as “negative.” These women were more likely to have better sexual satisfaction. Additionally, many women felt that, as they got older, they had a better understanding of their own sexual needs. This increased self-knowledge sometimes developed through self-exploration (masturbation), or sometimes arose from spending years with the same partner, becoming comfortable, and understanding one another’s bodies. Finally, as women got older, they felt more empowered and able to communicate these sexual needs to their partners. As they got older, they placed higher value on their own needs, and would communicate to their partner if something was not “working” sexually. One 52-year-old woman summarized her experience of sexuality and aging this way: “You know, I’m older… And a lot more wiser… you have to have… the other ingredients, not just physical attraction… but you got to like know the inside of a human being, you really do. And they have to know you.”

This study has several limitations. Women who respond to an advertisement about a study on sexuality, and who are willing to speak with a facilitator about sexuality may not be representative of the general population. However, women in this study were willing to discuss both positive and negative aspects of their sex lives, so we a wide range of experiences were captured. Several women mentioned that they were interested in participating in the study precisely because they had never talked to anyone about their sexuality. Another limitation is the exclusion of women who were not sexually active in the prior 12 months. We were interested in women’s current experiences of their sexual function; the experiences of sexually inactive women would not have been represented here. Additionally, we did not collect detailed data on occupation, current medication or substance use, or current health problems, all of which may affect women’s sexual function. Some women did discuss how job stress and medical issues impacted their sexual function, which have been explored in this manuscript. Future work should attend to these issues. Finally, qualitative research, which gathers rich and detailed information from a smaller number of women, is typically not widely generalizable.

This study has several strengths. We used a qualitative approach to explore changes in sexual function as women moved through midlife. Qualitative approaches give women the time and space to speak their own words about their experiences. This allows novel themes to emerge that may have not been previously considered. Additionally, the mix of individual interviews and focus groups allowed us to speak with women who were not comfortable talking in a group but also to capitalize on the group dynamics that can yield new information. Finally, we obtained a diverse variety of perspectives from women of different races and stages of menopause.

Implications for healthcare providers

These findings have important implications for providers who care for midlife women. First, it confirms prior studies suggesting vaginal dryness and low libido are common sexual complaints in this patient population, and providers should be familiar with evidence-based treatment for these issues. Second, our study highlights the importance of exploring the role of psychosocial factors, such as relationship issues or stress, in addition to biologic factors, such as hormone fluctuations, in female sexual dysfunction. Providers should query women specifically about relevant psychosocial factors, including relationship discord, stress from work or family-related issues, mood symptoms, and sleep. Pharmacologic treatments for sexual dysfunction may be inadequate unless psychosocial factors are also addressed. Third, increasing self-acceptance during midlife may be a key factor in maintaining sexual satisfaction with aging, even in the face of physical changes. When discussing sexual function with midlife women, healthcare providers should not assume that negative changes have occurred or that her sexual function is worse than her partner’s. Interventions that promote increased self-awareness and self-acceptance of one’s sexual needs as well as aging-related changes are likely to be important components of interventions for midlife women with sexual dysfunction.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important to recognize that not all changes in sexual function during midlife are negative, and when negative changes do occur, some women can find ways to adapt. Healthcare providers and researchers should recognize that each woman’s experience of sexual function during menopause is unique and nuanced. In addition, providers and researchers that work with midlife women can learn strategies, such as adapting sexual behavior and enhancing communication of sexual needs, from women who experience positive changes or successfully adapt to negative changes to help ensure that women can maintain satisfying sex lives as they age.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the women who participated in this study. We thank Dr. Sonya Borrero for her input regarding interpretation of the results. We thank the members of the Research Stakeholder Advisory Board, who provided feedback on the interview guide and assisted with interpretation of study results (Lee Hart RN, Judith Volkar MD, Constance Lappa MSW LCSW, and Patricia Coyle MD). Dr. Thomas is funded by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5K12HS022989-03). Dr. Thurston is funded by a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K24HL123565).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

Supplemental Digital Content

1. Qualitative Interview Guide, .docx

References

- 1.Leiblum SR, Koochaki PE, Rodenberg CA, Barton IP, Rosen RC. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: US results from the Women's International Study of Health and Sexuality (WISHeS) Menopause. 2006;13:46–56. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000172596.76272.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281:537–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ventegodt S. Sex and the quality of life in Denmark. Archives of sexual behavior. 1998;27:295–307. doi: 10.1023/a:1018655219133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biddle AK, West SL, D'Aloisio AA, Wheeler SB, Borisov NN, Thorp J. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder in postmenopausal women: quality of life and health burden. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2009;12:763–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas HN, Thurston RC. A biopsychosocial approach to women's sexual function and dysfunction at midlife: A narrative review. Maturitas. 2016;87:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Althof SE, Leiblum SR, Chevret-Measson M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2:793–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen RC, Barsky JL. Normal sexual response in women. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2006;33:515–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Avis NE, Zhao X, Johannes CB, Ory M, Brockwell S, Greendale GA. Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2005;12:385–98. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000151656.92317.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guthrie JR, Dennerstein L, Taffe JR, Lehert P, Burger HG. The menopausal transition: a 9-year prospective population-based study. The Melbourne Women's Midlife Health Project. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society. 2004;7:375–89. doi: 10.1080/13697130400012163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gracia CR, Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Mogul M. Hormones and sexuality during transition to menopause. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;109:831–40. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000258781.15142.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2009;16:442–52. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181948dd0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Family practice. 1996;13:522–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/13.6.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin SL. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Archives of sexual behavior. 2012;41:1319–20. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morse JM, Penrod J, Hupcey JE. Qualitative outcome analysis: evaluating nursing interventions for complex clinical phenomena. Journal of nursing scholarship : an official publication of Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing / Sigma Theta Tau. 2000;32:125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crabtree BFMW. Doing qualitative research in primary care: multiple strategies. 2. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, Johannes C, Longcope C. Is there an association between menopause status and sexual functioning? Menopause. 2000;7:297–309. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200007050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes R, Dennerstein L. The impact of aging on sexual function and sexual dysfunction in women: a review of population-based studies. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2:317–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.20356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;112:970–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898cdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woods NF, Mitchell ES, Smith-Di Julio K. Sexual desire during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause: observations from the Seattle Midlife Women's Health Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:209–18. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra G, Kuh D. Sexual functioning throughout menopause: the perceptions of women in a British cohort. Menopause. 2006;13:880–90. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000228090.21196.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fisher WA, Rosen RC, Eardley I, Sand M, Goldstein I. Sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction: the female experience of men's attitudes to life events and sexuality (FEMALES) study. The journal of sexual medicine. 2005;2:675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiblum S. Sexuality and the midlife woman. Psychol Women Quart. 1990;14:495–508. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basson R. The female sexual response: a different model. Journal of sex & marital therapy. 2000;26:51–65. doi: 10.1080/009262300278641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.