Abstract

Objective

To determine the association between health literacy, medication knowledge, and pain treatment skills with ED use of parents of children with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Methods

Parents of children 1 through 12-years-old with SCD were enrolled. Health literacy was assessed using the Newest Vital Sign. Parents completed a structured interview assessing knowledge of the dosage and frequency of home pain medications and an applied skills task requiring them to dose a prescribed pain medication. Underdosage was defined by too small a dose (dosage error) or too infrequent a dose (frequency error). The association between medication knowledge and applied skills with ED visits for pain over the past year was evaluated using Poisson regression adjusting for genotype.

Results

100 parent/child pairs were included; 50% of parents had low health literacy. Low health literacy was associated with more underdose frequency errors (38% vs. 19%, p=0.02) on the skills task. On medication knowledge, underdose dosage errors (adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (aIRR) 2.0, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 1.3–3.0) and underdose frequency errors (aIRR, 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.6) were associated with higher ED visits for pain. On the skills task, underdose dosage errors (aIRR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.4) and underdose frequency errors were associated with higher ED visits (aIRR 1.5 95% CI 1.1–2.1).

Conclusions

For medication knowledge and skills tasks, children of parents who underdosed pain medication had a higher rate of ED visits for pain. Health literate strategies to improve parents’ medication skills may improve pain treatment at home and decrease healthcare utilization.

Keywords: pain, pain medicine, sickle cell disease

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited hemoglobinopathy affecting an estimated 35,000 children and adolescents in the United States.1 Vaso-occlusive pain events, the hallmark of SCD, occur unpredictably and vary in severity and frequency. Approximately 90% of pain events in SCD require home pain management by patients and parents.2, 3 General recommendations for managing pain in SCD involve frequent pain assessment and the use of non-opioid and opioid medications to manage pain all while assessing for potential side-effects from pain medication use.4, 5 Collectively, home treatment of SCD pain is complex, requiring parents to possess knowledge and skills in health literacy sufficient to effectively manage pain in their children. Unsuccessful home treatment of pain may lead to an emergency department (ED) visit for pain.

An estimated 90 million American adults have low health literacy.6, 7 Health literacy is defined as “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services,” and encompasses the ability to use health literacy skills “to make appropriate health decisions.”7, 8 Low health literacy has been linked to problems with understanding of one’s medical condition,9–11 adherence to medication instructions,12, 13 and symptom management skills.14, 15 Within pain treatment, limited health literacy has been associated with increased pain medication dosing errors in children.16 Previous studies have shown that low health literacy serves as a potential mediator of health disparities, with low socioeconomic status, less than high school education, and black race found to be risk factors.7, 17 Unfortunately, parents of children with SCD possess many of the same sociodemographic risk factors associated with low health literacy, which may lead to poor pain management skills.18, 19

In this study, we aimed to examine the association between parent health literacy and pain medication knowledge and applied skills in parents of children with SCD. We hypothesized that parents with low health literacy would demonstrate more errors in medication knowledge and applied skills than parents with adequate health literacy. We hypothesized that low health literacy and errors in medication knowledge and applied skills would be associated with higher ED visits for pain.

Patients and Methods

Study Participants

Parents or legal guardians of children ages 1 through 12-years-old with SCD were recruited during routine clinic visits and ED visits at a Midwest children’s hospital. A child was eligible if chart review revealed a genotype consistent with sickle cell disease (SS, SB0, SC, SB+). Parents of children over 12 years old were excluded given the potential influence of an older child’s health literacy on pain treatment. Parents were required to be at least 18 years of age. Legal guardians other than the parent were eligible if they “(took) care of the child most of the time when they have pain.” If multiple parents were present, the parent that “brought the child to the doctor most often” was assessed. Participants were excluded if the parent had already completed the study, was non-English speaking, or presenting for child maltreatment or non-accidental trauma within the ED. The study was approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board. Parents signed a 6th grade level written consent and the children provided assent for age >7.

Study Design

This was a cross sectional study of parents of children with SCD to assess health literacy, pain medication knowledge, and pain medication skills in relation to ED utilization. Participant recruitment occurred in multiple settings to facilitate adequate enrollment from December 2014-January 2016. Within the clinic setting, parents of children with SCD were approached during their scheduled visit and the research procedures were completed after the clinic visit. Within the ED, a trained research assistant approached eligible parents and research procedures were completed within the ED. After consent, participants completed a brief demographic survey; the Newest Vital Sign (NVS), a validated measure of health literacy; a pain medication knowledge review; and an applied pain treatment skills assessment. Chart review was conducted to determine patient characteristics (i.e., age, SCD genotype and disease characteristics, coexisting conditions) and the participant’s current prescribed pain medication regimen. Parents received a gift card for participation to offset the time required to complete the study.

Measures

Health Literacy Assessment

The Newest Vital Sign (NVS) is a validated, orally administered, six-question test to assess health literacy.20 The NVS was responsive in previous studies of parents and has been associated with ED use.21 The NVS was scored based on the published score categorization; low health literacy (0–3 correct) and adequate health literacy (4–6 correct).20 The NVS is a common measure of health literacy and has differentiated health outcomes in studies of adolescents, parents, and adults.22–24

Pain Medication Knowledge Review

To assess pain medication knowledge, parents were asked to recall the names, doses, and dosing intervals for all current prescribed pain medications used for treatment of pain for their child at home.25 This approach has been used previously and shown that medication knowledge is related to medication adherence, disease control, and hospitalizations in adult patients.25 We expanded the protocol by including doses and dosing interval. This list was compared to the child’s medical record for current pain medications including non-opioid and opioid pain medications (except tramadol) updated in the last 13 months. All parents of children with SCD recruited within the ED had had a routine clinic visit within the last 12 months. Data was quantified as: 1) the percent of medications recalled; 2) the percent of names (generic or name brand) correct; 3) the percent of doses correct by mg, mL, or pill count as well as under or overdose dosage error; and 4) the percent of dosing intervals (frequency) correct as well as under or overdose frequency error.

Applied Pain Treatment Skills Assessment

To assess applied pain treatment skills, parents were presented with a pain medication (liquid or pill) to mimic administration of pain medications. This medication skills assessment has been used previously in health literacy research utilizing as needed pain medication and modified to include liquid medication.26 Parents of patients under 8 years of age were provided with instructions for a liquid pain medication and parents of patients ages 8 years and older were provided instructions for a pill pain medication (Supplemental Appendix S1). To assess medication dosing, parents were presented with a dosing tray that contains 24 slots representing each hour of a day. Parents were given the prescription bottle and instructed to place the liquid solution or plastic pills into the slots to demonstrate how much and when they would provide doses of the medication to their child throughout the day.27 Parents were provided with a standardized script (Supplemental Appendix S1) to ensure that parents felt free to continue to dose for the full 24 hours rather than stopping at one dose.

Incorrect dosing of the medication was measured in five ways: 1) underdose dosage error [less than 2 pills or liquid medication weight less than 20% of standard)]; 2) underdose frequency error [less frequently than every 4 hours]; 3) overdose dosage error [more than 2 pills or liquid medication weight greater than 20% of standard)]; 4) overdose frequency error [more frequently than every 4 hours]; and 5) maximum dose error by exceeding more than the recommended daily dose (>5 doses).26 Liquid medication standard was independently measured by two investigators (A.M. and M.M.) to determine standard dose. Dose error greater or less than 20% of standard was based on previous liquid medication studies.28

Primary Outcome: ED Use for Pain

The child’s medical chart was reviewed to determine ED use for pain over the previous 1 year. A physician diagnosis of sickle cell disease pain was required for documentation of a sickle cell pain episode. Visits were not excluded if the child had additional diagnoses such as fever. Chart reviews were conducted and then verified by a second research assistant, with discrepancies recorded and reviewed with the principal investigator. Nearly all children with SCD in our community are seen and hospitalized in our institution. ED visits included visits ending in discharge or hospitalization.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics were compiled using descriptive statistics and compared with location of recruitment with appropriate tests (t-tests, chi-square tests, and Wilcoxan rank sum tests). The NVS was utilized to dichotomize parents into low (≤3 correct) health literacy or adequate (≥4 correct) health literacy. The mean percent of errors in pain medication knowledge (medication recall, name, dosage, and frequency) and the applied pain treatment skills (dosage errors, frequency errors, and maximum dose errors) were calculated and compared for parents with low health literacy versus adequate health literacy in parents using chi-square analyses.

The NVS, pain medication knowledge, and applied pain treatment skills task variables were individually compared with ED visits for pain using a Poisson regression model adjusting for child SCD genotype.

Prior research shows that 55% of parents had low health literacy and approximately 60% of patients can identify the medication name.25, 29 In order to determine whether a difference exists in naming pain medications, 97 parents were needed to find a difference of 30% between adequate and low health literacy caregivers; 70% identifying medication name (adequate health literacy) compared to 40% (low health literacy).

Results

Study Sample

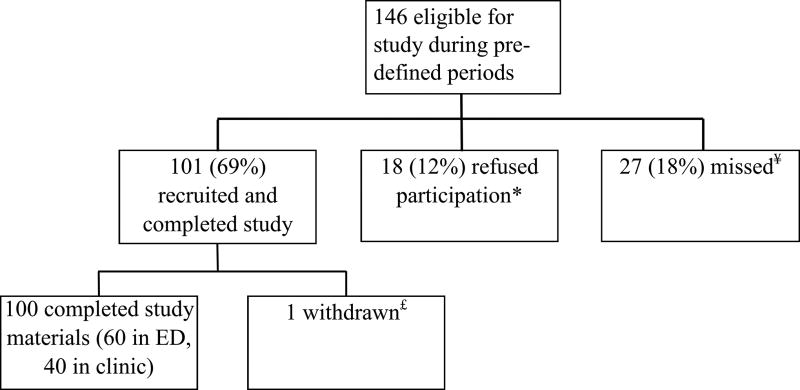

Out of 146 eligible participants, 100 parents/child pairs agreed to participate with 40% recruited in the SCD clinic and 60% in the ED (Figure 1). The majority of parents were of Black/African American descent (90%), median age was 31.5 years (range 18–80 years), and 56% had education beyond high school (Table 1). The family’s household income was <$30,000 in 68% of households. Children were a median of 6 years old (range 1–12 years). The majority of children were SS/Sβ0 (62%) genotype. Most children had been prescribed hydroxyurea within the prior year (61%).

Figure 1.

Study Participants

* Reasons for refusal: No reason given (10), did not want to prolong ED stay (3), child does not need pain medication (2), did not want to provide social security number to receive giftcard (2), crying child (1)

¥ Missed: No reason given (8), concurrent enrollment with same or another study (2), sleeping and could not assent (1), could not approach due to ongoing ED care (1)

£ Withdrawn: Parent decided to not participate after signing consent but before starting the procedure

TABLE 1.

Parent and Child Demographic Factors by Location of Recruitment

| Location | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total N=100(%) |

Clinic N=40(%) |

ED N=60(%) |

P Value |

| Parent | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.22C + | |||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Asian | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Black / African American | 90 (90) | 38 (95.0) | 52 (86.6) | |

| White / Caucasian | 1 (1.0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Other | 5 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.3) | |

| Parent Age | 0.95T | |||

| Mean ± SD | 33.3 ± 9.1 | 33.18 ± 10.2 | 33.31 ± 8.4 | |

| Foreign Born | 12 (12.0) | 4 (10.0) | 8 (13.3) | 1.000C + |

| Educational Attainment | 0.93C + | |||

| 8th grade or less | 2 (2.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (1.7) | |

| Some high school | 11 (11.0) | 5 (12.5) | 6 (10.0) | |

| Graduated High School / GED | 31 (31.0) | 13 (32.5) | 18 (30.0) | |

| Some college / Technical degree | 44 (44.0) | 15 (37.5) | 29 (48.3) | |

| College degree (BA, BS) | 8 (8.0) | 4 (10.0) | 4 (6.6) | |

| Advanced degree (MA, PhD, MD, JD) | 4 (4.0) | 2 (5.0) | 2 (3.4) | |

| Work outside the home | 59 (60.2)* | 24 (63.2) | 35 (58.3) | 0.59C |

| What is your household income in a year? | 0.75C + | |||

| Less than $20,000 | 58 (58.0) | 21 (52.5) | 37 (61.7) | |

| $20,001–30,000 | 20 (20.0) | 9 (22.5) | 11 (18.3) | |

| $30,001–40,000 | 13 (13.0) | 5 (12.5) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Over $40,001 | 9 (9.0) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (6.7) | |

| Health Literacy | <0.01C | |||

| Low (0–3) | 50 (50.0) | 13 (32.5) | 37 (61.7) | |

| Adequate (4–6) | 50 (50.0) | 27 (67.5) | 23 (38.3) | |

|

| ||||

| Child | ||||

|

| ||||

| Age (Mean ± SD) | 6.4 ± 3.7 | 7.1 ± 3.5 | 5.9 ± 3.8 | 0.11T |

| Hydroxyurea prescribed | 61 (61.0) | 31 (77.5) | 30 (50.8) | <0.01C |

| Genotype | <0.01C + | |||

| SS/SBO | 62 (62.0) | 32 (80.0) | 30 (50.0) | |

| SC/SB+ | 33 (33.0) | 8 (20.0) | 25 (41.6) | |

| Other | 5 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (8.4) | |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 14 (14.0) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (8.5) | <0.05C |

| Public | 86 (86.0) | 33 (82.5) | 54 (91.5) | 0.22C + |

| Healthcare utilization | ||||

| Treat and release ED visits (Mean ± SD) | 0.7 ± 1.3 | |||

| Hospitalizations | 0.5 ± 1.3 | |||

| Total ED Visits | 1.3 ± 2.4 | |||

Exact test

t-test;

Chi-square test;

Wilcoxon rank-sum test

missing values

Health Literacy

Health literacy

Half of parents had low health literacy (50%). More parents recruited in the ED had low health literacy than parents recruited in clinic (61% vs. 32.5%, p=0.005).

Health Literacy and Pain Medication Knowledge and Applied Treatment Skills

Parents with low health literacy made more underdose frequency errors (38% vs. 19%, p=0.02) on the pain treatment skills task. Health literacy was not associated with errors on the medication knowledge review or other errors on the applied treatment skills.

Health literacy and ED use

Low health literacy was not associated with ED use.

Pain Medication Knowledge Review

Pain medication knowledge review

Comparing chart review to parent pain medication recall, 37% of parents did not report medications identified by chart review. Of those not reported, 25% were ibuprofen or acetaminophen and 12% were opioid pain medications. When considering only opioid medications, a mean of 12.4% (SD 29.7%) of the medications were not recalled and 16.5% (SD 34.2%) of the medication names were incorrectly recalled (Table 2). Parents recalled an underdose of medication often; 17% of parents recalled a lower dose than prescribed and 31% recalled a less frequent medication dosage interval. Fewer parents recalled higher doses; 17% of parents recalled a higher dose of medication and only1% of parents recalled a more frequent medication administration interval.

TABLE 2.

Opioid Pain Medication Review and ED Utilization

| Variables | Mean (Standard Deviation (SD)) of Percent Recall or Percent of Parents Making Error |

Adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (aIRR) (95% Confidence Interval-(CI)) ED Visits for Pain+ |

|---|---|---|

| Medications Not Recalled | 12.4 (29.7) | 1.3 (1.2–1.3)* |

| Name Not Recalled | 16.5 (34.2) | 0.99 (0.99–1.01) |

| Underdose errors | ||

| Dosage | 17% | 2.0 (1.3–3.0)* |

| Frequency | 31% | 1.7 (1.2–2.6)* |

| Overdose errors | ||

| Dosage | 17% | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) |

| Frequency | 1% | n/a |

ED visits include treat and release ED visits and ED visits resulting in hospitalization

P<0.05

Pain medication knowledge and ED use

Fewer pain medications recalled were associated with increased ED visits for pain (adjusted Incidence Rate Ratio (aIRR) 1.3, 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI) 1.2–1.3) (Table 2). Underdose dosage errors were associated with 200% higher ED visits for pain (aIRR 2.0, 95% CI 1.3–3.0). Underdose frequency errors were also associated with 70% higher ED visits for pain (aIRR 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.6). No relationship was found between recalled pain medication overdose errors or pain medication name recall and ED use.

Applied Pain Treatment Skills

Applied pain treatment skills

Several parents made underdose errors on the applied pain treatment skills task; 17% of parents made a dosage error and 28% a frequency error. Parents also made overdose errors; 12% made a dosage error, 7% a frequency error, and 30% a maximum dose error.

Applied pain treatment skills and ED use

Parental underdose dosage errors were associated with 60% more ED visits for pain (aIRR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.1). Parental underdose frequency errors were also associated with 50% greater ED visits for pain (aIRR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1–2.1). No relationship was found between overdose errors and ED visits.

Discussion

Our results show that parents of children with SCD demonstrated high rates of low health literacy. Moreover, parents with low health literacy made more underdose frequency errors on an applied pain medication skills task. In addition, when lower pain medication dose and frequency occurred during the skills task by parents of children with SCD, significantly higher ED utilization for pain by their child was identified. Using multiple methods including a pain medication knowledge recall and pain medication skills task, we found a 50% to 200% higher rate of ED visits for pain in children with SCD whose parents underdosed pain medication.

We found high rates of low health literacy- 50% of parents had low health literacy. Because patients with SCD have a complex, chronic illness that requires parents to give their children medication, the high rate of low health literacy for these parents is alarming. Other studies of SCD have interestingly found lower rates of low health literacy, but such findings may be a result of the instrument utilized to assess health literacy.21, 30 To date, research has found that the Newest Vital Sign is a more sensitive measure of health literacy, particularly within parents.30, 31 In addition, parents of children with SCD that had low health literacy made a greater number of underdose frequency errors on the applied pain medication skills task. Such findings were consistent with previous research linking low health literacy and increased pain medication dosing errors in children.16

Management of SCD pain is complex requiring parents to possess knowledge and skills to effectively manage their child’s pain. Thus, the high rate of errors in pain medication knowledge and on an applied pain management skills task is concerning and represents an opportunity to improve how care is provided to these families. Our study found that parents demonstrated a variety of errors in dose and frequency on the pain medication review and applied skills with a greater propensity for errors in underdosing pain medication. In addition, underdosing dose and frequency errors were related to higher rates of ED visits for pain in children with SCD. Such findings support what has been found in other conditions showing that poor medication knowledge leads to poor disease outcomes and increased ED visits.25 Collectively, medication knowledge and skill appear to be important in treating SCD pain at home based on the association we found with higher ED utilization.

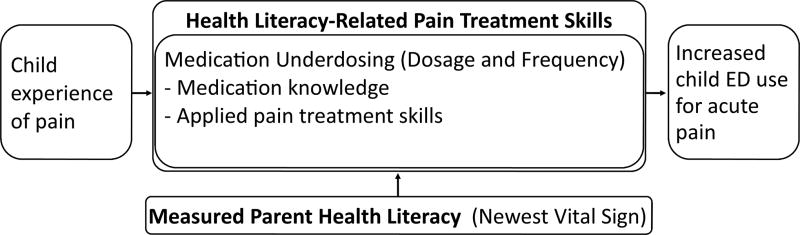

Interestingly, we found that inadequate pain treatment knowledge and skills were more highly related to ED utilization than low health literacy, which was different from previous research demonstrating that low health literacy results in poor performance on medication skill tasks which resulted in higher ED utilization.13, 25, 32, 33 From this we propose a model of the relationship between health literacy, health literacy-related pain treatment skills, and healthcare use for pain (Figure 2). We found that health literacy does not have a direct effect on ED utilization for pain, but potentially works through pain medication knowledge and skills. The health literacy measure used in this study was a general measure of health literacy and may assess factors unrelated to tasks important to ED use in SCD. However, the pain medication knowledge and skills are related to health literacy conceptually, were significantly associated on one skill task, and were associated with increased ED use.

Figure 2.

Model for Health Literacy Skills and ED Use for Pain

Importantly, we found that performance on the pain medication knowledge and skills task was associated with higher ED utilization. As such, the pain medication dosing skills of parents are important for children with SCD where pain medication is often needed to manage disease prior to presenting to the ED.2, 3 Though pain-related ED use is frequent in children with SCD, 90% of pain management occurs at home.2, 3 By affecting pain medication skills at home with an intervention, there is potential to decrease pain-related ED use. Future interventions could address effective pain management at home by addressing reasons parents underdose medications and focus training regarding medication on appropriate use of medication.

The skills assessment adapted for SCD in this study will aid future studies and clinical teaching for pain medications. Using the skills assessment in a research setting may help define the skills or serve as an outcome measure to evaluate a health literacy-related intervention to improve pain medication dosing skills.26 The potential to use the skills assessment in a healthcare setting such as the clinic or ED to teach a parent or patient until they reach correct dosing on the task (teach-to-goal technique), may improve parents’ use of pain medication.34 Improving a parent’s ability to dose pain medication may reduce their child’s ED utilization for pain.

This study has several limitations. The applied pain skills assessment was a simulation of home treatment during a pain episode. The relationship with ED use may not be significant if studied in a prospective study. Despite the understanding this study adds, we did not address why parents underdosed medication. Additional studies are needed to understand the pathway leading from medication dosing to ED utilization. Other factors may have contributed to the use of the ED other than medication knowledge, applied skills, or genotype, which were included in the regression model. Because of the limited sample size given our local population of SCD within the age range, we could not adjust for additional variables beyond genotype. Though attempts were made to recruit every patient within the age range at our institution, this remains a convenience sample of patients and may not represent the population or patients at other institutions.

Conclusions

Parents of children with SCD have high rates of low health literacy which is related to underdosing pain medication. Consistent across pain medication knowledge and applied skills, underdosing of pain medication either by giving a lower dose or giving medication less frequently is associated with a higher rate of ED utilization for pain. Health literate strategies to improve parents’ pain medication dosing skills in future interventions or clinical care may improve at home care for pain and decrease ED utilization for pain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the research assistants and coordinators that helped make this study possible: Eva Igler, Sylvia Torres, Adam Drent, Duke Wagner, Nichole Graves, Mark Nimmer, Katherine Driscoll, Lauren Thomas, Jaime Voss, and Erica Gleason.

Grant/Award Number: UL1TR001436.

Abbreviations Key

- SCD

Sickle Cell Disease

- ED

Emergency Department

- NVS

NVS Newest Vital Sign.

Footnotes

Contributors’ Statements Page

Andrea K Morrison and Matthew P Myrvik: Drs. Morrison and Myrvik conceptualized and designed the study, carried out the analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

David C Brousseau, Amy L Drendel, J Paul Scott, Alexis Visotcky, and Julie A Panepinto: Drs. Brousseau, Drendel, Scott, and Panepinto and Alexis Visotcky contributed to the design of the study, interpreted the analysis, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of work.

No authors had financial conflicts of interest applicable to this manuscript.

Supplemental Appendix S1: Applied Pain Treatment Skills Prescription and Script

References

- 1.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and reshospitalizations for sickle cell disease. The Journal of the American Medical Association, JAMA. 2010;303(13):1288–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dampier C, Ely E, Brodecki D, O'Neal P. Home management of pain in sickle cell disease: a daily diary study in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24(8):643–647. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro BS, Dinges DF, Orne EC, et al. Home management of sickle cell-related pain in children and adolescents: natural history and impact on school attendance. Pain. 1995;61(1):139–144. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00164-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benjamin LJ, Dampier CD, Jacox AK. Guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain in sickle-cell disease. Glenville, IL: American Pain Society; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rees DC, Olujohungbe AD, Parker NE, et al. Guidelines for the management of the acute painful crisis in sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2003;120(5):744–752. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman ND, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Literacy and health outcomes. Evid Rep. Technol. Assess. (Summ) 2004;87:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. p. 368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratzan SC, Parker RM. Introduction. In: Selden CR, Zorn M, Ratzan SC, Parker RM, editors. National Library of Medicine Current Bibliographies in Medicine: Health Literacy. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams MV, Baker DW, Honig EG, Lee TM, Nowlan A. Inadequate literacy is a barrier to asthma knowledge and self-care. Chest. 1998;114(4):1008–1015. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.4.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Peel J, Baker DW. Health literacy and knowledge of chronic disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51(3):267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Cross JT, Marin E, Green K, Bennett CL. Health literacy and patient knowledge in a Southern US HIV clinic. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(11):747–752. doi: 10.1258/0956462042395131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalichman SC, Ramachandran B, Catz S. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapies in HIV patients of low health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(5):267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding of prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman RB, Jones SK, Lin A, Robin AL, Muir KW. Influence of parental health literacy and dosing responsibility on pediatric glaucoma medication adherence. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(3):306–311. doi: 10.1001/archopthalmol.2011.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pulgaron ER, Sanders LM, Patino-Fernandez AM, et al. Glycemic control in young children with diabetes: The role of parental health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin HS, Wolf MS, Dreyer BP, Sanders LM, Parker RM. Evaluation of consistency in dosing directions and measuring devices for pediatric nonprescription liquid medications. JAMA. 2010;304(23):2595–2602. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yin HS, Johnson M, Mendelsohn AL, Abrams MA, Sanders LM, Dreyer BP. The health literacy of parents in the United States: a nationally representative study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S289–98. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chau M, Thampi K, Wight V. Basic Facts about Low-income Children, 2009: Children under Age 18. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radcliffe J, Barakat LP, Boyd RC. Family systems issues in pediatric sickle cell disease. In: Brown RD, editor. Comprehensive Handbook of Childhood Cancer and Sickle Cell disease: A Biopsychosocial Approach. New York, NY: Oxford; 2006. pp. 496–513. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiss B, Mays M, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Annals of family medicine. 2005;3(6):514. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison AK, Schapira MM, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Measuring Health Literacy in Caregivers of Children: A Comparison of the Newest Vital Sign and S-TOFHLA. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2014 doi: 10.1177/0009922814541674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chari R, Warsh J, Ketterer T, Hossain J, Sharif I. Association between health literacy and child and adolescent obesity. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linnebur LA and Linnebur SA. Self-Administered Assessment of Health Literacy in Adolescents Using the Newest Vital Sign. Health Promot Pract. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1524839916677729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin HS, Parker RM, Sanders LM, et al. Effect of Medication Label Units of Measure on Parent Choice of Dosing Tool: A Randomized Experiment. Acad Pediatr. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenahan JL, McCarthy DM, Davis TC, Curtis LM, Serper M, Wolf MS. A drug by any other name: patients' ability to identify medication regimens and its association with adherence and health outcomes. J Health Commun. 2013;18(Suppl 1):31–39. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy DM, Davis TC, King JP, et al. Take-Wait-stop: A Patient-Centered Strategy for Writing PRN Medication Instructions. J Health Commun. 2013;18:40–48. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.825675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Waite K, et al. Helping patients simplify and safely use complex prescription regimens. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):300–305. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin HS, Parker RM, Sanders LM, et al. Liquid Medication Errors and Dosing Tools: A Randomized Controlled Experiment. Pediatrics. 2016 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison AK, Schapira MM, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Brousseau DC. Low caregiver health literacy is associated with higher pediatric emergency department use and nonurgent visits. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carden MA, Newlin J, Smith W, Sisler I. Health literacy and disease-specific knowledge of caregivers for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;33(2):121–133. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2016.1147108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burks LM, Feller TM, Davies HW, Myrvik MP. Health literacy among adolescents/emergency adults with sickle cell disease; National Conference on Pediatric Psychology; April, 2013; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin HS, Mendelsohn AL, Wolf MS, et al. Parents' medication administration errors: role of dosing instruments and health literacy. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(2):181–186. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lokker N, Sanders L, Perrin EM, et al. Parental misinterpretations of over-the-counter pediatric cough and cold medication labels. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1464–1471. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baker DW, DeWalt DA, Schillinger D, et al. "Teach to goal": theory and design principles of an intervention to improve heart failure self-management skills of patients with low health literacy. J Health Commun. 2011;16(Suppl 3):73–88. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.