Summary

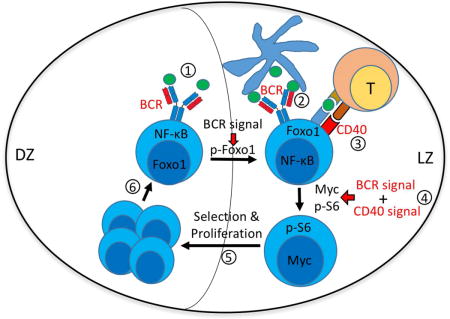

Positive selection of germinal center (GC) B cells is driven by B cell receptor (BCR) affinity and requires help from follicular T helper cells. The transcription factors c-Myc and Foxo1 are critical for GC B cell selection and survival. However, how different affinity-related signaling events control these transcription factors in a manner that links to selection is unknown. Here we showed that GC B cells reprogram CD40 and BCR signaling to transduce via NF-κB and Foxo1 respectively, whereas naïve B cells propagate both signals downstream of either receptor. Although either BCR or CD40 ligation induced c-Myc in naïve B cells, both signals were required to highly induce c-Myc, a critical mediator of GC B cell survival and cell cycle reentry. Thus, GC B cells rewire their signaling to enhance selection stringency via a requirement for both antigen receptor and T cell-mediated signals to induce mediators of positive selection.

eTOC Blurb

Luo et al show that CD40 and BCR signaling in GC B cells is rewired to control very different pathways, and both signals are required for optimal induction of c-Myc, suggesting a mechanism of signaling directed positive selection of GC B cells.

Introduction

In germinal centers (GCs), B cell undergo somatic hypermutation, affinity maturation and class-switch recombination to generate long lived memory B cells and plasma cells, which are the source of high affinity antibodies against pathogens (Shlomchik and Weisel, 2012a, b). The GC is an important component of humoral immunity whereas GC dysregulation is associated with immunodeficiency, autoimmune disease and cancer (Al-Herz et al., 2014; DeFranco, 2016; Hamel et al., 2012).

Positive selection of high affinity GC B cells is the key to affinity maturation, but the detailed process of positive selection is poorly understood. At the most basic level, cells with higher affinity for antigen must get enhanced signals that lead to either better survival, proliferation, or both. These signals logically would involve the BCR directly, but could also include signals gathered by the B cell based on successful presentation of antigen (Ag) to T cells. The latter could include cytokines (such as IL-21) and surface receptors, but prominently is expected to include CD40 signals. Lack of CD40 or its ligand, or administration of anti-CD40L at any time during the GC reaction, results in complete loss of GC B cells (Kawabe et al., 1994; Renshaw et al., 1994; Takahashi et al., 1998; Xu et al., 1994), confirming a key role for CD40 signals that must emanate from follicular T helper (Tfh) cells.

The relative importance of these signals in mediating positive selection has been debated and remains to be fully clarified. We reported that the BCR in GC B cells was desensitized and suggested that its major function may be to take up antigen for presentation to T cells, which in turn would deliver positively selecting signals to GC B cells (Khalil et al., 2012). Victora et al., using a photoactivatable GFP system and in vivo imaging, concluded that clonal expansion is triggered by T cell:GC B cell interactions in the GC light zone, and that T cells discriminate among GC B cells based on the amount of Ag captured and presented (Victora et al., 2010). Taking into account zonal distribution of cells and functions in the GC, their data supported a model in which GC B cells in the light zone (LZ) interact with Tfh to receive positive signals; positively selected GC B cells then migrate to the dark zone (DZ) to expand and accumulate mutations, after which they migrate back to the LZ to undergo selection again (De Silva and Klein, 2015; Victora et al., 2010). They further concluded that T cell help was the limiting factor in GC selection, not competition for Ag (Victora et al., 2010). Similarly, Liu et al. elucidated a complex interplay between Tfh and GC B cells, in which reciprocal signals mediated by ICOSL on the B cell and CD40L on the T cell convey positive selection via increased expression of ICOSL on selected B cells (Liu et al., 2015). Again, their data indicated a paramount role for T cell derived signals, in particular CD40L. Shulman et al. came to parallel conclusions again using in vivo imaging (Shulman et al., 2014). In subsequent work Gitlin et al. proposed that T cell-mediated selection led to shortened S phase duration and hence faster cycle times (Gitlin et al., 2014). Despite the remarkable advances that implicated a role of T cell-derived signals, exactly how such signals were coupled to selective advantage—whether that be ICOSL upregulation or reduction in cell cycle duration—has yet to be determined.

Two transcription factors, c-Myc and Foxo1, have been shown to be important in the positive selection process (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012; Sander et al., 2015). Although c-Myc expression appears limited to a small fraction of light zone GC B cells (centrocytes) in mature germinal centers, genetic evidence from two groups demonstrated that c-Myc is essential in GC initiation, maintenance and positive selection (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). In addition, c-Myc positive GC B cells are actively dividing, suggesting these cells are positively selected (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). Foxo1 also regulates GC B cell selection: Foxo1 deficiency abrogates the DZ and results in defective affinity maturation and class-switching (Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Sander et al., 2015).

The signaling pathways regulating these transcription factors that mediate selection in GC B cells remain poorly understood. Insights into how external signals are transduced to regulate these transcription factors could provide a key missing link to connect the findings about the importance of localized T cell and antigen signals to the mechanisms that underlie positive selection. Our initial studies of BCR signaling in GC B cells validated the concept that GC differentiation resulted in dramatic reprogramming (Khalil et al., 2012); however, we could not connect this to transcriptional regulation nor integrate it into the emerging network of both BCR and T cell mediated signals that contribute.

Here, using a combination of assays on freshly isolated ex vivo GC B cells, genetic ablation, specific inhibitors and in vivo delivery of key stimuli to in situ GC B cells, we both re-evaluated BCR signaling potential and defined the GC B cell-specific responses of the key T cell signal receptor, CD40. We confirmed and extended our prior finding that BCR signaling was attenuated, yet identified that BCR-mediated and AKT-dependent phosphorylation of Foxo1 remained uniquely robust (in contrast to other AKT-mediated outputs such as generation of p-S6). CD40-mediated signaling via any PI3-kinase related pathway, on the other hand, was markedly reduced in GC B cells compared to naïve B cells. In contrast, we found that although qualitatively altered, NF-κB mediated signaling downstream of CD40 in GC B cells was similar compared to naïve B cells (but is missing downstream of BCR signaling in GC B cells). Finally, we linked this to induction of c-Myc, the critical step in mediating positive selection in GC B cells (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). We did this first in vitro and then in vivo either spontaneously or after delivery of CD40 or BCR ligands to GC B cells. Taken together the data suggest a new model that links both BCR and CD40 signals to modulation of transcription factors that underlie selection. Whereas naïve B cells can engage both PI3K-AKT and NF-κB pathways downstream of either BCR or CD40, leading to c-Myc upregulation, GC B cells require both signals to do so effectively. Thus, engagement of this key positive selection step requires two signals both of which require affinity for Ag, possibly explaining how GC B cells establish stringent requirements that drive affinity selection.

Results

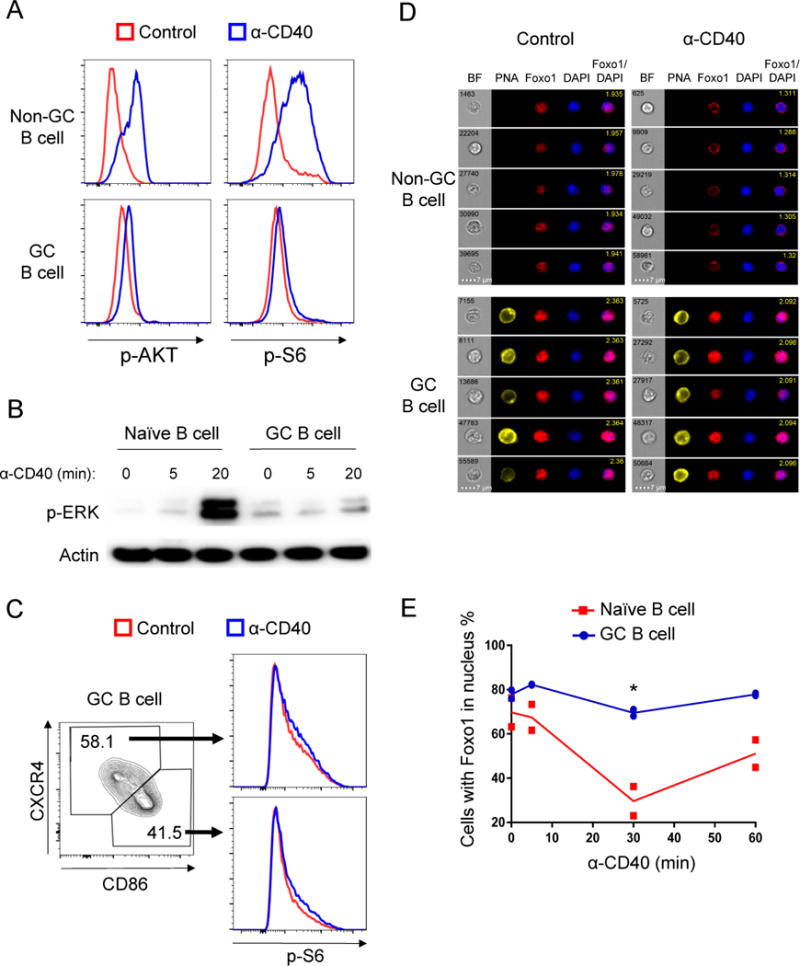

AKT and ERK pathways are attenuated in response to CD40 ligation in GC B cells

To investigate CD40 signaling in GC B cells, we first performed phospho-flow cytometry for p-AKT and p-S6 after crosslinking CD40 on splenocytes isolated from immunized mice near the peak of a GC response. Most GC B cells interact with Tfh cells only for a short period of time (Liu et al., 2015). However, in contrast to naïve B cells, short-term CD40 stimulation led to minimal phosphorylation of AKT or S6 in gated GC B cells (Figures 1A and S1A-B). Similarly, western blotting on bead-purified GC B cells or naïve B cells that had been similarly treated showed generation of p-ERK only in naïve B cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. AKT and ERK pathways are dampened in GC B cells stimulated by CD40 signals.

(A) Splenocytes from day 14 NP-CGG immunized B1-8i mice were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody or PBS (Control) for 20 min and stained for p-AKT (S473) and p-S6 (S235/236). Live Ig-lambda+ GC B cells (PNA+) and non-GC B cells (PNA−) were gated. Histograms show representative examples of at least three independent experiments; spleen cell pools from two mice were tested in each experiment.

(B) Magnetic bead-purified naïve B cells and GC B cells were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody for 0, 5 and 20 minutes, cells were then harvested for western blot. Shown is one experiment representative of three independent experiments.

(C) GC B cells were stimulated as described in (A) and were gated on LZ and DZ to compared p-S6. Data represent one of three independent experiments.

(D and E) Splenocytes from NP-CGG immunized B1-8i mice were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody for 0, 5, 30, 60 minutes. The localization of Foxo1 was examined by Amnis Imagestream cytometry. Two independent experiments were performed with cells pooled from two to three mice in each experiment. (D) Representative images of 30 min stimulated non-GC B cells and GC B cells captured by the Imagestream. Object number is shown in BF (Bright field) picture and similarity score is shown in merged picture (Foxo1/DAPI). (E) Histogram showing the fraction of cells with nuclear Foxo1 (high Foxo1/DAPI similarity score). *P≤0.05 See also Figure S1.

The GC can be divided geographically into DZ and LZ. Studies have revealed differences in gene expression and surface marker expression, and ongoing work seeks to delineate the functional differences between these two zone and cell populations (Allen et al., 2007a; Allen et al., 2007b; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Gitlin et al., 2014; Hauser et al., 2007; Sander et al., 2015; Schwickert et al., 2007; Victora et al., 2012; Victora et al., 2010). LZ GC B cells express activation markers such as CD86 and CD83 and they are more likely to get T cell help (Shlomchik and Weisel, 2012a; Victora et al., 2010) while DZ GC B cells express higher amounts of CXCR4. To test whether LZ and DZ GC B cells respond differently to CD40 ligation, we used CD86 and CXCR4 as markers to delineate LZ and DZ cells and p-S6 as an index readout. As shown in Figure 1C and Figure S1C, p-S6 generation is equally dampened in DZ and LZ GC B cells. Considering 30% to 50% of GC B cells are LZ in our system, had there been substantial differences between DZ and LZ in any response we would have observed bimodal peaks in phospho-flow data, but we observed only a unimodal distribution for all the signaling readouts discussed in this article. Thus, we infer that LZ and DZ GC B cells are not intrinsically different in responding to BCR or CD40 signals. In addition, we also found no differences between IgM GC B cells and switched GC B cells in generation of p-S6 (Figure S1D-E).

When activated by phosphorylation, AKT can inactivate Foxo1 by phosphorylating and displacing it from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Tzivion et al., 2011). In agreement with dampened AKT phosphorylation downstream of CD40 ligation, we did not find significant Foxo1 translocation following CD40 stimulation in GC B cells (Figure 1D-E). Despite these findings, and in keeping with previous data on human tonsillar GC B cells (Koopman et al., 1997; Liu et al., 1989), CD40 stimulation effectively rescued GC B cells from apoptosis in vitro (Figure S1F), suggesting that other signaling pathways may be activated in GC B cells to mediate this effect.

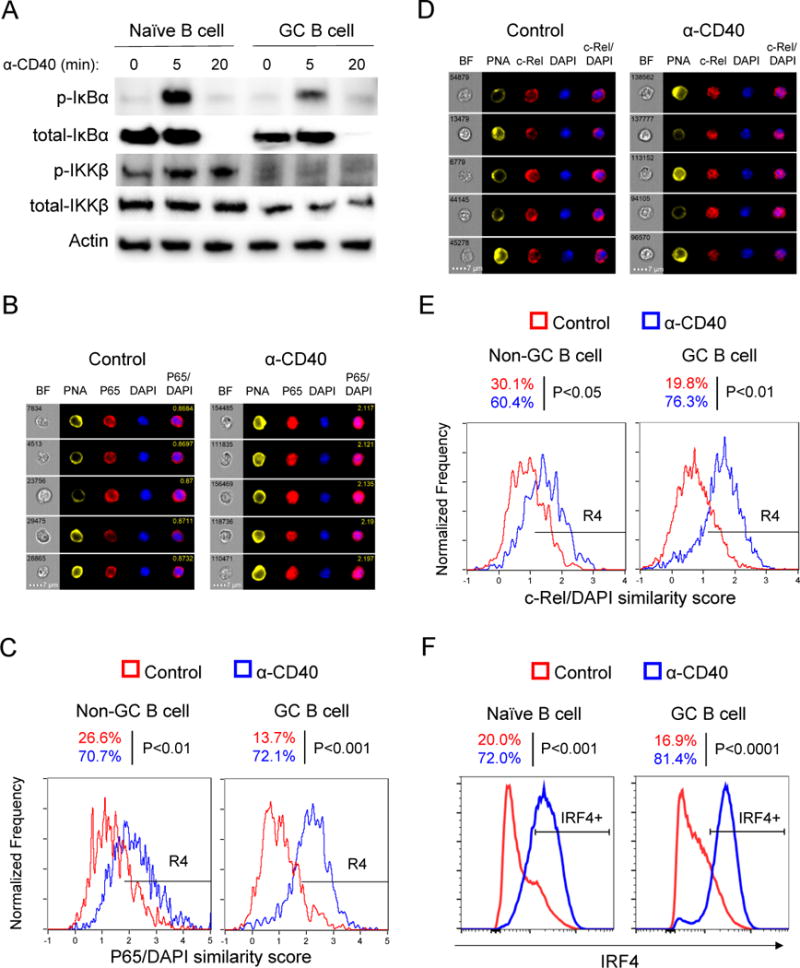

NF-κB activation downstream of CD40 ligation is preserved in GC B cells

The NF-κB pathway is known to transmit survival signals and can be activated by CD40 in naïve B cells (Mizuno and Rothstein, 2005). Indeed, in GC B cells CD40 stimulation induced degradation of IκBα, a key step to initiate NF-κB signaling, with kinetics similar to naïve B cells (Figure 2A). Interestingly, GC B cells did show reduced phosphorylation of IκBα and P65 compared to naïve B cells (Figure 2A and Figure S1G-H). This was probably due to reduced expression of IκB kinase β (IKKβ) (Figure 2A). Critically, CD40 induced functional NF-κB activity in GC B cells indicated by the translocation of P65 (RelA) and c-Rel into the nucleus and the upregulation of NF-κB target IRF4 (Figures 2B-F). Hence the NF-κB pathway is functional downstream of CD40 signals in GC B cells.

Figure 2. CD40 signals specifically activate the NF-κB pathway.

(A) Magnetic bead-purified naïve B cells and GC B cells were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody for different time spans. Cell lysates were examined by western blot. Shown is one experiment representative of three independent experiments. Cells were purified from three or four mice in each experiment.

(B-E) Splenocytes from immunized B1-8i or MEG mice were stimulated with anti-CD40 antibody or PBS (Control) for 30 min and localization of NF-κB subunits P65 (B-C) and c-Rel (D-E) was examined by Imagestream. (B and D) Representative images of GC B cells; (C and E) P65/DAPI and c-Rel/DAPI similarity score from Non-GC B cells and GC B cells are plotted, R4 gate represents cells with P65 (C) or c-Rel (E) in the nucleus (high similarity score). Three independent experiments were performed with similar results and similar results were observed in both B1-8i and MEG mouse models.

(F) Total B cells from immunized MEG mice were cultured with CD40 antibody or PBS (Control) for 4 hours. IRF4 expression was examined by flow cytometry, gated on naïve or GC B cells. Three independent experiments were performed. See also Figure S1.

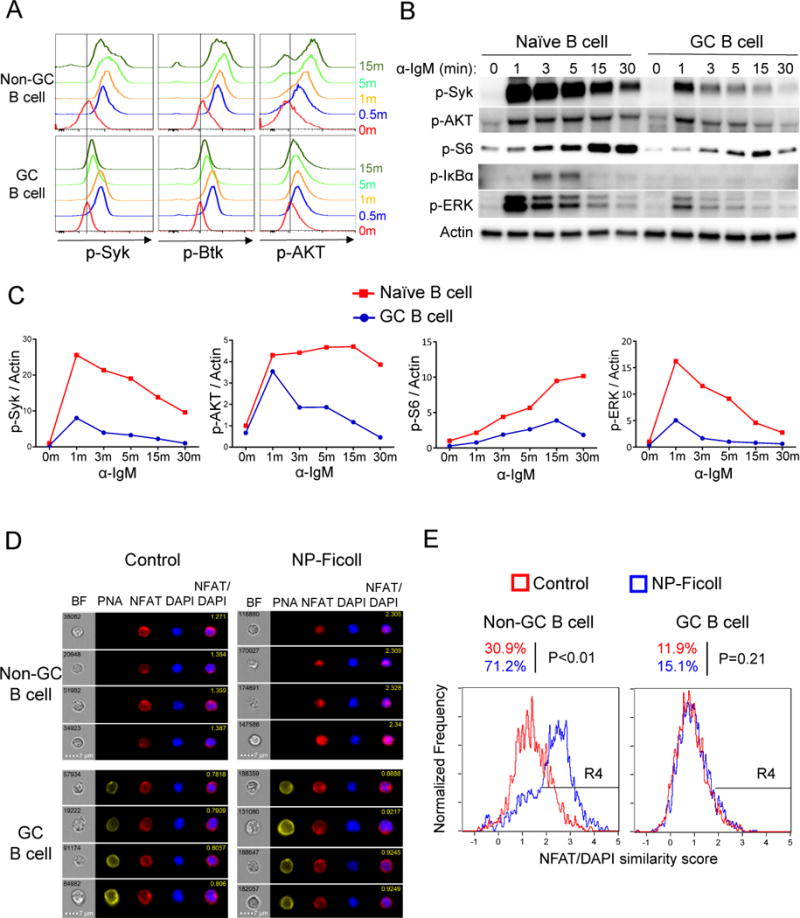

BCR crosslinking induces transient and weak activation of Syk and AKT in GC B cells

Partial activation of CD40 downstream pathways in GC B cells suggests that CD40 might not be the only signal regulating GC B cell function. In particular, based on the impacts of genetic alterations in the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway on GC B cell responses (Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Sander et al., 2015), we expected to find a ligand that would effectively activate this pathway. Therefore, we focused on identifying weaker but meaningful signals through more detailed kinetic studies and using more sensitive techniques—via a revised, non-methanol based phospho-flow protocol—than previously employed (Khalil et al., 2012). As just shown above, CD40 did not transmit signals to activate AKT or inactivate Foxo1, arguing against its role in the process. Though we confirmed dampened BCR signaling in GC B cells, we found that it was not completely absent, but rather had different kinetics and quality in GC B cells compared to naïve B cells. Notably, BCR stimulation of GC B cells induced weak but definite phosphorylation of the upstream kinases Syk and Btk within 1 minute, which was much less sustained and did not reach the same amplitude compared to naïve B cells (Figure 3A-C). Apparently, this transient BCR signal was not able to fully activate GC B cells since most downstream BCR signaling events were substantially attenuated, including phosphorylation of AKT, S6, IκBα and ERK (Figure 3A-C); NFAT was also not activated by BCR stimulation in GC B cells (Figure 3D-E).

Figure 3. BCR signals selectively induce transient activation of Syk and AKT in GC B cells.

(A) Total splenocytes pooled from two immunized MEG mice were stimulated with goat anti-IgM for different time periods. Cells were fixed, permeabilized and stained for p-Syk (Y352), p-Btk (Y223) and p-AKT (S473). Live Ig-lambda+ GC B cells (PNA+) and non-GC B cells (PNA−) were gated.

(B-C) Western blots were performed with bead-purified MEG naïve and GC B cells stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for different durations. Quantitation of western blot data are shown in (C) with signals normalized to actin and further normalized to naïve B cells at time 0 giving a value of 1.

(D-E) Splenocytes from immunized B1-8i mice were stimulated with NP-Ficoll or PBS (Control) for 5 min. NFAT nuclear translocation was examined by Imagestream analysis. Representative images are shown in (D), and statistical analysis is shown in (E). R4 gates represent cells with nuclear NFAT translocation (high NFAT/DAPI similarity score). Data are representative results from one of three independent experiments with statistical analysis for all experiments.

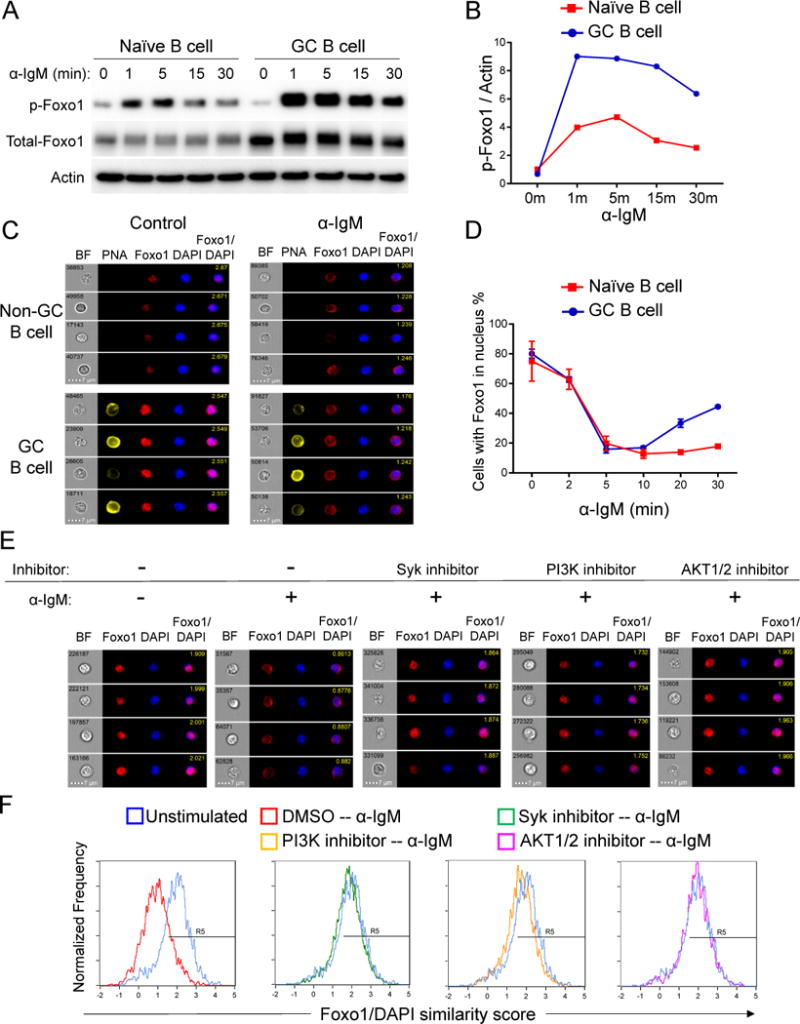

BCR signals selectively inactivate Foxo1 in GC B cells through the Syk-PI3K-AKT pathway

Although BCR signaling is clearly inhibited in GC B cells, we reasoned that it might still be sufficient to activate AKT and contribute to Foxo1 regulation. Foxo1 is involved in controlling differentiation of GC B cell DZ cells, as well as class switching and affinity maturation within the GC (Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Sander et al., 2015). In addition, though DZ GC B cells almost uniformly contain nuclear Foxo1, a small fraction of LZ GC B cells were found to lack nuclear Foxo1 (Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Sander et al., 2015), suggesting that certain signals received by LZ GC B cells are able to cause Foxo1 inactivation, presumably by activating AKT, the major known kinase that regulates Foxo1 (Tzivion et al., 2011). Indeed, strong phosphorylation of Foxo1 was observed in GC B cells in response to BCR ligation (Figure 4A-B). BCR stimulation efficiently displaced Foxo1 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm within 5 minutes (Figure 4C-D), and this effect was blocked by Syk, PI3K or AKT inhibitors (Figure 4E-F). The magnitude and efficacy of Foxo1 regulation by the BCR was surprising given the relatively weak and transient activation of upstream mediators such as Syk. Therefore, these data demonstrated that BCR signals in GC B cells are rewired to effectively inactivate Foxo1 via the Syk-PI3K-AKT axis, but that other downstream branches are much less active compared to naïve B cells.

Figure 4. BCR signals efficiently phosphorylate and inactivate Foxo1 through the PI3K-AKT pathway in GC B cells.

(A) Magnetic bead-purified naïve and GC B cells were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for indicated time spans, harvested and examined by western blot. Data are from one representative experiment of three independent experiments. Cells were purified from three to four MEG mice in each experiment.

(B) Quantitation of western blot data in (A). Signal was normalized to actin and further normalized to naïve B cells at time 0, giving a value of 1.

(C and D) Total splenocytes from MEG mice were stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for 0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 minutes. Localization of Foxo1 was examined by Imagestream. Two independent experiments were performed. Cells were pooled from 2 to 3 mice in each experiment. (C) Representative images of Non-GC B cells and GC B cells stimulated for 0 (Control) and 5 minutes; (D) Quantitation of cells with Foxo1 in the nucleus based on Foxo1/DAPI similarity score (mean ± SD).

(E and F) Splenocytes from immunized MEG mice were treated with or without 5 M Syk inhibitor (BAY61-3606), 10 M PI3K inhibitor (Ly294002) or 5 M AKT1/2 kinase inhibitor for 30 min and then stimulated with anti-IgM antibody for 5 min. Localization of Foxo1 was examined by Amnis Imagestream. Two independent experiments were performed, and splenocytes were pooled from two to three mice in each experiment. (E) Representative images of GC B cells with Foxo1/DAPI similarity score shown in the merged picture; (F) Foxo1/DAPI similarity score is compared between control (DMSO treated with no stimulation) and treated cells. R5 gates represent cells with Foxo1 in nucleus (high Foxo1/DAPI similarity score).

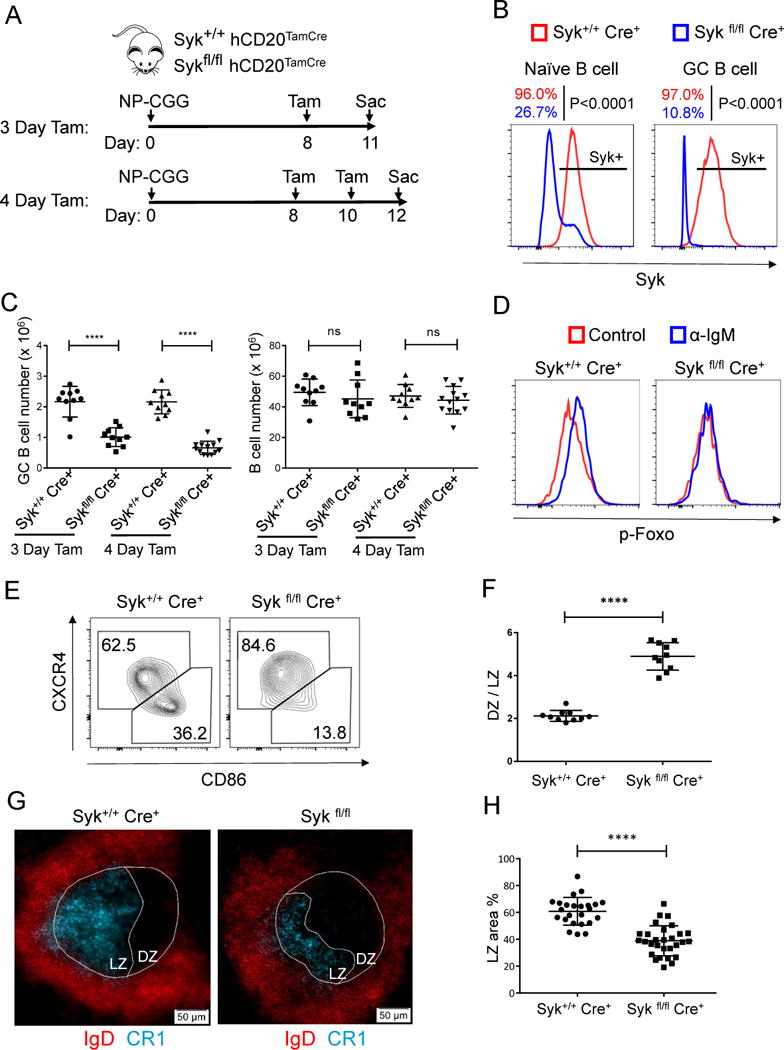

Syk signaling is important in maintaining the GC light zone through inactivation of Foxo1

Foxo1 activity is required for the maintenance of the GC B cell DZ program (Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Sander et al., 2015). From this—and from the Syk-, PI3K-, and AKT-dependent circuit elucidated above—we predicted that loss of BCR signaling would result in loss of Foxo1 inactivation, thereby enhancing the DZ. To test this, we used a tamoxifen-inducible human CD20-driven Cre (Khalil et al., 2012) to delete Syk in B cells after establishment of an ongoing GC reaction. One dose of tamoxifen treatment efficiently reduced Syk protein levels in both GC B cells and naïve B cells within 3 days (Figure 5A-B). Syk deletion resulted in gradual depletion of GC B cells, with a ~2- and 3-fold loss of GC B cells within 3 and 4 days of tamoxifen treatment, respectively, while no significant effect on total B cells was observed (Figures 5A, 5C and S2A), suggesting that Syk signaling is essential for GC maintenance.

Figure 5. Syk signaling is important in maintaining the GC light zone through inactivation of Foxo1 and is required for GC maintenance.

(A) Time line illustration of tamoxifen (Tam) treatment for NP-CGG immunized Syk+/+ hCD20TamCre and Sykfl/fl hCD20TamCre mice. Mice were immunized with NP-CGG and given one dose of tamoxifen orally on day 8 post immunization and analyzed on Day 11 (3 days post tamoxifen); for 4-day tamoxifen treatment, tamoxifen were given on Day 8 and Day 10 post immunization and mice were analyzed on Day 12.

(B) Mice were analyzed by flow cytometry for Syk expression levels in naïve and GC B cells 3 days post tamoxifen treatment. Shown is one representative histogram of Syk staining and statistical data represents seven mice from two independent experiments.

(C) Splenocytes from (A) were analyzed by flow cytometry. GC B cells were gated as B220+ PNA+ CD95+ cells. At least three independent experiments were performed with total of 10 to 13 mice from each group tested (mean ± SD). ns, not significant; ****P≤ 0.0001.

(D) Splenocytes from (A) (3 Day Tam) were stimulated with 20 g/ml anti-IgM antibody for 5 minutes, IgM GC B cells were gated and analyzed for p-Foxo by flow cytometry. Shown are representative histograms for three independent experiments. See also Figure S2B for statistical analysis.

(E and F) Light zone (LZ) and dark zone (DZ) GC B cells from (A) (3 Day Tam) were identified by CD86 and CXCR4 staining. (E) Representative flow cytometry analysis of GC B cells; (F) Quantitation of flow cytometry data as the ratio of cells in the DZ to LZ per the gating in (E) (mean ± SD, n=10 for each group).

(G-H) Spleen cryosections from (A) (3 Day Tam) were analyzed by immunofluorescent staining for GC (IgD and PNA) and light zone (CR1). (G) Representative images; (H) Statistical analysis of the percentage of LZ area in the GC (mean ± SD). Each dot represents one GC. Three to 5 typical GC from one spleen, and 6 to 8 mice in each group from 3 independent experiments were analyzed. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤ 0.001, ****P≤0.0001 See also Figure S2

In agreement with the results from the Syk inhibitor, Syk-deficient GC B cells could not phosphorylate Foxo1 upon BCR stimulation (Figures 5D and S2B). As hypothesized, Syk deletion increased the DZ/LZ ratio among GC B cells within 3 days of tamoxifen treatment (Figure 5E-H). Thus, these data link Syk signals to Foxo1 regulation and in turn to the expression of the LZ phenotype. We conclude that BCR signaling, in a Syk dependent pathway that signals via PI3K and AKT, is responsible for regulating the GC B cell DZ to LZ transition in a Foxo1-dependent manner.

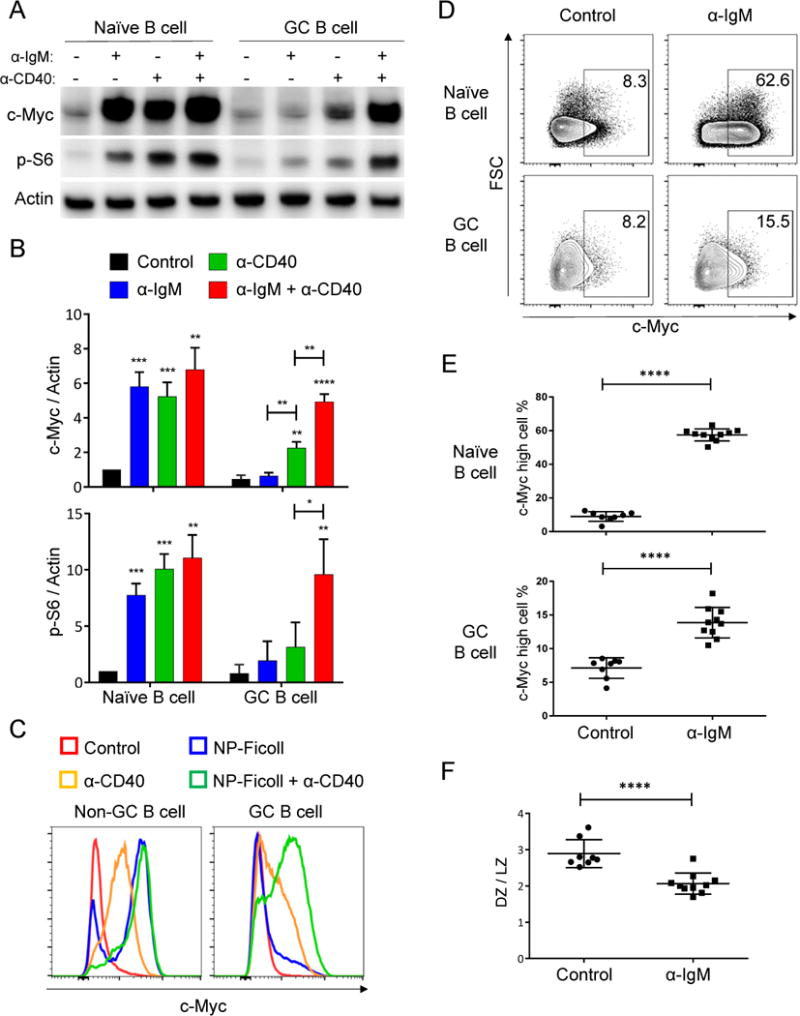

BCR and CD40 signals synergistically induce c-Myc and p-S6 in GC B cells

These data suggest that BCR signaling might license GC B cells to enter and/or stay in the LZ so as to interact with Tfh cells that are concentrated in the LZ. Selection of GC B cells is thought to be mediated by T cell signals within the LZ that in turn induce c-Myc expression, which is required for GC B cell survival and positive selection (De Silva and Klein, 2015). Though c-Myc is required for GC maintenance, its expression is restricted to a minor subset of LZ GC B cells (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). The signaling process that turns on c-Myc in these LZ GC B cells has not been clear. c-Myc is an NF-κB target (Duyao et al., 1990; La Rosa et al., 1994); in other cell types Foxo factors can repress c-Myc signaling (Gan et al., 2010; Wilhelm et al., 2016). In addition, Foxo factors can also directly antagonize NF-κB activity (Kim et al., 2008; Lin et al., 2004). As shown above, in GC B cells, signaling via both the BCR and CD40 are rewired such that BCR signals propagate via Foxo1 inactivation but not effectively via NF-κB, whereas the converse is true downstream of CD40. In contrast, in naïve B cells both receptors propagate both signals. We therefore postulated that in GC B cells optimal c-Myc expression would require dual BCR and CD40 signals. In keeping with this, in naïve or non-GC B cells, either BCR or CD40 stimulation robustly induced c-Myc expression. However, these individual stimuli failed to do so in GC B cells. Only combined BCR and CD40 stimulation in GC B cells strongly and synergistically induced c-Myc, whereas the effects of dual signals were less than additive in naïve B cells (Figure 6A-B). We confirmed this finding by flow cytometry in the B1-8i mouse model, which can class switch to IgG1 (Figure 6C and Figure S3A). Comparing IgM GC B cells with class-switched GC B cells showed very similar results in response to BCR and CD40 stimulation (Figure S3B). Interestingly, c-Myc induction by the signals is independent of CXCR4 expression, indicating that LZ (CXCR4lo) and DZ (CXCR4hi) GC B cells are both capable of responding to BCR and CD40 signals, even though the availability of these signals may be different between the two zones (Figure S3C-D).

Figure 6. BCR and CD40 signals synergistically induce c-Myc and p-S6 in GC B cells.

(A) Naïve and GC B cells were purified from MEG mice and cultured with indicated stimuli for 2 hours (unstimulated as Control), harvested and examined by western blot for c-Myc and p-S6 (S235/236). Data are results from one of three independent experiments. Cells were pooled from three to four mice in each experiment.

(B) Quantitation of (A): c-Myc/actin ratio and p-S6/actin ratios were normalized to naïve B cells, with Control given a value of 1. (mean + SD, “ * ” on the bar shows significance compared to Control).

(C) Total B cells were purified from immunized B1-8i mice and stimulated in vitro as indicated for 2 hours (unstimulated as Control). Cells were then fixed, permeabilized and examined by flow cytometry for c-Myc expression. One representative example of five independent experiments is shown. Similar results were obtained by using 2.5 μg/ml biotinylated CD40 antibody preincubated with streptavidin.

(D and E) Day 10 NP-CGG immunized IgMi mice were injected intravenously with goat anti-IgM or goat IgG isotype control and sacrificed four hours after injection. Splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for c-Myc expression in naïve and GC B cells. (D) Representative flow cytometry data. (E) Quantitation and statistical analysis of c-Myc high cells among naïve or GC B cells from flow cytometry data. (Control: n=8, α-IgM: n=10; each dot represents a single mouse with mean ± SD).

(F) LZ and DZ distribution of GC B cells from (D) was analyzed by flow cytometry based on CD86 and CXCR4 expression (mean ± SD). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P ≤0.0001 See also Figure S3.

Consistent with this, inhibition of Syk blocked CD40-mediated survival in GC B cells but not in naïve B cells in vitro (Figure S3E). Hence, in comparison to naïve B cells, GC B cell signaling via BCR and CD40 are rewired with respect to c-Myc induction, the induction of which is known to be critical for GC B cell positive selection (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). In addition to c-Myc, p-S6 is also critical for regulating cell growth and protein synthesis (Dang, 1999; Dufner and Thomas, 1999; van Riggelen et al., 2010). Very recently, Ersching et al. identified the phosphorylation of S6 and associated mTOR activation as key events associated with selection for GC B cell entry into cell cycle as a result of exogenous induction of T cell help signals (Ersching et al., 2017). Intriguingly, BCR and CD40 ligation also synergistically induced p-S6 in GC B cells, whereas either signal alone resulted in only weak generation of p-S6 (Figure 6A-B), further suggesting that the positive selection of GC B cells can be facilitated by dual BCR and CD40 signals. These results are fully consistent with those of Ersching et al. in that both show a requirement for T cell-derived signals while our work suggests that responsive cells would have received a recent BCR signal to “license” the CD40 signal in the setting studied by Ersching et al (see below).

Given these in vitro data, we tested in vivo whether a BCR signal would induce c-Myc in GC B cells and also augment the fraction of GC B cells with LZ phenotype. To do this, we used IgMi mice, which have B cells that express an IgM BCR but cannot secrete any immunoglobulin (Waisman et al., 2007), thus allowing delivery in vivo of a BCR crosslinking signal via anti-IgM injection (which would simply bind to serum IgM in a wild-type mouse). Such in vivo BCR stimulation significantly increased the percentage of c-Myc high GC B cells (Figure 6D-E; Isotype Control: 7.1% vs anti-IgM: 13.9%). That only a small fraction of GC B cells upregulated c-Myc in response to the BCR signal was in keeping with the fact that only a small fraction of GC B cells would have received a sufficient T cell-derived CD40 signal at any given interval. Importantly, this in vivo BCR signal increased the LZ fraction among GC B cells (Figure 6F), directly supporting the conclusion drawn from Syk deletion, which had the opposite effect (Figure 5E-H). These in vitro and in vivo data demonstrate the importance of the BCR signal in regulating the DZ to LZ transition as well as cooperating with CD40 signaling to induce c-Myc for positive selection.

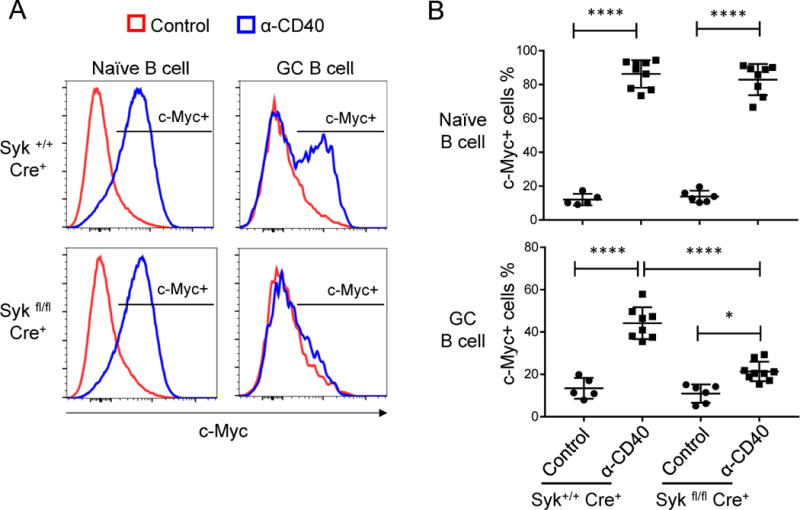

Blocking BCR signaling in GC B cells in vivo reduces c-Myc induction by CD40 signals

To further test our model that GC B cells need both BCR and CD40 signals to up regulate c-Myc for positive selection, we asked if a CD40 signal would induce c-Myc without a valid BCR signal. To accomplish this, we took advantage of the tamoxifen inducible Cre system to delete Syk specifically in B cells during peak of GC reaction (as discussed above). In vivo CD40 stimulation was induced by IV injection of anti-CD40 antibody (FGK) for four hours. This treatment induced c-Myc in all naïve B cells regardless of Syk expression levels (Figure 7A-B), as expected from our in vitro data showing that ligation of CD40 alone was sufficient for c-Myc induction in naïve B cells. GC B cells responded very differently: in Syk sufficient GC B cells, CD40 stimulation induced c-Myc in a population of GC B cells (Figure 7A-B); this subset presumably also received an in vivo BCR signal during this four hour time course. Syk-deficient GC B cells could induce c-Myc in some cells in response to CD40 stimulation in vivo, but to a much lesser extent compared to Syk sufficient GC B cells (Figure 7A-B). Notably, though as expected, Syk-deficient GC B cells did not phosphorylate Foxo1 in response to BCR stimulation (Figures 5D), they did respond to CD40 stimulation to translocate NF-κB equally well compared to Syk sufficient GC B cells (Figure S4A-B), demonstrating that the CD40 signal was appropriately received by these cells.

Figure 7. BCR signals are required for optimal c-Myc induction in GC B cells in vivo.

(A-B) Syk+/+ hCD20TamCre and Sykfl/fl hCD20TamCre mice were immunized with NP-CGG. One dose of tamoxifen was administrated orally on day 8 post immunization. Mice at day 11 post immunization were injected intravenously with 50 μg of anti-CD40 antibody (FGK) or Isotype control (rat IgG2a) and analyzed 4 hours after injection. c-Myc expression was examined by flow cytometry and cells were gated on naïve B cells (B220+ CD38+ PNA−) and GC B cells (B220+ CD38− PNA+). Representative flow cytometry data are shown in (A) and statistical analysis is shown in (B). Data represent three independent experiments with total of 5 to 9 mice from each treatment group (mean ± SD). *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ***P≤0.001, ****P≤0.0001 See also Figure S4.

To rule out the possibility that Syk could also mediate BAFF (Tybulewicz et al., 2013) or CD40 signaling to promote cell survival, we compared Syk-sufficient and deficient B cells in response to BAFF and CD40 stimulation. We found that Syk-deficient B cells could respond normally to BAFF or CD40 stimulation to process P100 to P52 (Figure S4C). In addition, BAFF and CD40 promoted B cell survival independent of Syk expression (Figure S4D). Consistent with these findings, we only detected Syk phosphorylation in B cells upon BCR stimulation, but not BAFF or CD40 stimulation (Figure S4E). These data are in agreement with and extend a more recent report that found no role for Syk in BAFFR signaling (Hobeika et al., 2015). We conclude that in vivo induction of c-Myc by CD40 signaling requires Syk and thus presumably BCR signaling for synergy, as was the case in vitro. This is also in accord with our observation that ongoing Syk signaling is required for GC maintenance (Figures 5C and S2A).

Discussion

A fundamental objective in GC biology is to understand the mechanism by which antigen selects higher affinity V region mutant cells with such efficiency. Progress has been made on understanding cellular movements and interactions in the GC at the imaging level. Transcription and gene regulation are broadly reprogrammed in the GC, and recent discoveries using gene deletion or overexpression in two separate lines of work have linked Foxo1 expression to GC zonal segregation and affinity maturation and Myc expression to positive selection (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012; Sander et al., 2015). These were seminal results. However, the signaling pathways that connect these external interactions to induction of the correct transcriptional programs in a time, location, and affinity-dependent way have not been elucidated. Previously we showed that BCR signaling in the GC was reprogrammed from its state in the naïve B cell (Khalil et al., 2012), but how this contributed to functional selection in the GC was not clarified. In fact, others and we interpreted our prior findings to mean that the BCR functioned mainly if not exclusively to gather antigen and that T cell mediated signals were primary if not exclusively involved in GC B cell selection.

Here we have explored a second major signaling axis in the GC B cell, CD40, which is stimulated by cognate interactions with Tfh within the GC. A major contribution of our work is to show that the response to this signal is also dramatically reprogrammed in the GC B cell compared to its state in the naïve B cell. This is important because naïve B cells have previously been used as model systems by which to extrapolate to GC B cells (Cho et al., 2016; Jellusova et al., 2017); this extrapolation may not be warranted given the different responses of naïve B cells and GC B cells to CD40 ligation. Most importantly we found that CD40 activates the canonical NF-κB pathway, but—in contrast to the situation in naïve B cells—is not responsible in the GC B cell for PI3 kinase signal initiation as in GC B cells we could detect no signal propagation to regulate AKT signals. Klein et al have shown that two canonical NF-κB subunits RelA and c-Rel have important but distinct roles in GC B cell function: c-Rel is critical for GC maintenance while RelA is important in plasma cell differentiation (Heise et al., 2014). Our data demonstrate that CD40 ligation results in efficient nuclear translocation of both RelA and c-Rel in GC B cells, so, based on the work of Klein, it would seem that CD40 signals can mediate both GC maintenance and plasma cell differentiation. Hence, it is likely that other signals would have to integrate with CD40 in GC B cells to determine whether GC B cells differentiate into PC or else self-renew for GC maintenance.

Two models have been proposed to explain the mechanism of GC B cell selection and affinity maturation: BCR signaling-based selection or T cell help-based selection (Allen et al., 2007a; Shlomchik and Weisel, 2012a). Our initial finding that BCR signaling in GC B cells was desensitized supported the second model and prompted further development of the notion that T cell-mediated signals select high affinity GC B cells (Khalil et al., 2012). Results from Victora et al. favor this model by showing that delivering T cell help in vivo can direct GC B cells to the DZ for expansion (Victora et al., 2010). Additional in vivo studies emphasize the unique nature of cognate T-B interactions in the GC leading to bidirectional CD40-CD40L and ICOS-ICOSL signaling to optimize selection (Liu et al., 2015). Very recently, ephrin signaling was implicated as an additional mode to fine tune T-B interactions in the GC to promote selection (Lu et al., 2017). In all cases the emphasis and data have been focused on T cell derived signals with selection coming from BCR-mediated Ag uptake and consequent presentation to T cells, rather than from BCR signaling.

Two recent papers have also provided data on BCR signaling in GC B cells. Mueller and colleagues nicely showed that the Nur77-GFP reporter was expressed in a subset of GC B cells, and more prominently in LZ than DZ GC B cells (Mueller et al., 2015). A limitation of this study is that, in addition to BCR, CD40 signals can also induce Nur77 expression ((Zikherman et al., 2012) and our unpublished data) and while ibrutinib, a Btk inhibitor, reduced the fraction of GC B cells that were GFP positive (Mueller et al., 2015), this was only about a 50% reduction. While these authors showed that exogenous anti-CD40 induced lower GFP levels than did BCR, they did not show a dose-titration and it appears that a suboptimal concentration of CD40 Ab (1ug/ml) may have been used, as in our hands a more optimal concentration would be 10-20 fold higher. Hence, the effects of CD40 may have been underestimated. Taking this into account, Nur77-GFP expressing GC B cells are thus likely a mixture of CD40-stimulated, BCR-stimulated and possibly dual-stimulated cells.

Regardless, and as noted by the authors, this study did not link BCR signaling to any downstream events or determine the contribution of it to affinity maturation. Nonetheless, these data do agree with our finding that CD40-dependent induction of c-Myc depends on Syk expression in vivo and provide independent evidence that a subset of GC B cells do spontaneously transduce signals via the BCR. Since Syk-deficiency in this context fully and specifically targets the BCR we could clearly show that BCR signaling is required for DZ to LZ transition and to synergize with CD40 signals to induce c-Myc in GC B cells.

Nowosad et al. (Nowosad et al., 2016) also confirmed in an independent system our prior findings that BCR signaling was generally attenuated in the GC (Khalil et al., 2012), but showed that very strong membrane-bound BCR signals could overwhelm the phosphatase-dependent signal attenuation of GC B cells at least based on localized p-Syk generation. In agreement with our prior and current findings, they also found that this upstream signaling did not propagate to the nucleus in the form of NF-κB translocation, while CD40 ligation could promote translocation in GC B cells. Again, they did not connect this to downstream events or positive selection and did not appreciate that CD40 signals were rewired to block critical PI3K signals selectively in the GC. The current work builds substantially beyond these prior upstream signaling studies to show that BCR signal regulates Foxo1 via PI3K and AKT and to identify the synergy between this signal and the NF-κB -mediated CD40 signals delivered by T cells, with both required to initiate positive selection.

Thus, a key contribution of the current work is to reintroduce direct BCR signals into a revised model of positive selection that integrates BCR with T cell (CD40L) derived signals, each with non-redundant roles leading to synergistic outcomes (see diagram of signaling and GC selection model in Figure S6A-B). Our in vitro and in vivo data reveal that rewired BCR and CD40 signaling pathways in GC B cells results in a requirement for both signals to induce c-Myc expression and to generate p-S6, both of which are intimately linked with selection for reentry into the cell cycle in GC B cells (Ersching et al., 2017). In contrast, naïve B cells can achieve activation with c-Myc and p-S6 induction from either signal, because BCR and CD40 signals are overlapping in activation of multiple downstream pathways in naïve B cells (Dal Porto et al., 2004; Elgueta et al., 2009). c-Myc has been shown to serve as division timer to regulate B cell responses (Heinzel et al., 2017), and its expression has been tightly linked as a critical and non-redundant step in positive selection in the GC (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012). Recently Mayer et al. have bolstered this linkage by demonstrating that Myc+ GC B cells have a very low rate of apoptosis, indicative of positive selection (Mayer et al., 2017).

It has been proposed that GC B cell proliferation occurs mainly in the GC DZ, segregated from selection mediated by FDC and Tfh that would occur mainly in the LZ, where scattered c-Myc positive cells are observed (Allen et al., 2007a; De Silva and Klein, 2015). Despite the differences in the environment and proliferative potential between LZ and DZ GC B cells, we did not detect differences in terms of how they are wired to acutely respond to signals delivered via BCR or CD40 stimulation. This is a separate issue from the fact that GC B cells in different zones are likely to actually receive different external signals. This finding is in line with the limited differences in the gene expression profiles between LZ and DZ GC B cells (Allen et al., 2007b; Hauser et al., 2007; Schwickert et al., 2007; Victora et al., 2012; Victora et al., 2010) and fits with the observation that GC B cells can transit rapidly between zones. Rather, the nature of signals received likely control zonal presence and phenotype: from both Syk deletion and in vivo ligation experiments—each of which had distinctive effects on DZ/LZ distributions—we infer that in GC B cells the BCR signal promotes survival and LZ presence.

There are two possible explanations for how BCR signals could affect localization: BCR signals may direct DZ GC B cells to travel to the LZ when they get a valid BCR signal; or GC B cells may cross the interface to enter the LZ in a random fashion but then need a BCR signal to remain in the LZ. The latter model is attractive since zonal recirculation, in addition to zonal crossing, have been observed in live imaging of the GC (Allen et al., 2007b; Hauser et al., 2007; Schwickert et al., 2007). Nonetheless, since BCR signals may occur in both zones, it is possible that both modes of zonal regulation could be operative.

In any case, the LZ in turn is where most Tfh interactions can occur, allowing a CD40 signal to also be delivered, inducing c-Myc. In this way, not only would the BCR signal synergize with CD40 in a cell-intrinsic way to induce c-Myc, but it also could influence B cell localization such that the chances of receiving a concordant CD40 signal are increased. We thus propose that this rewiring and its signaling and localization consequences (Figure S6A-B), interpreted in the context of key data from others on the roles of Foxo1 and c-Myc (Calado et al., 2012; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2015; Dominguez-Sola et al., 2012; Sander et al., 2015), explains the unique stringency of Ag-driven selection in the GC.

STAR METHODS

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Mark J Shlomchik (mshlomch@pitt.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mice were maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions supervised by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). 6- to 12 week old, age and sex matched mice were used for all animal experiments.

METHOD DETAILS

Mice and Immunization

B1-8i knock-in (“B1-8i”) BALB/c and IgM B1-8 BCR transgenic BALB/c mice (referred to as MEG) were previously described (Hannum et al., 2000; Khalil et al., 2012; Sonoda et al., 1997). The IgMi mouse was described previously and maintained on a C57Bl/6 (B6) background (Waisman et al., 2007). Sykfl (Syktm1.2Tara) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory, and were crossed to hCD20TamCre mice on the B6 background (Khalil et al., 2012). 6- to 12-week-old mice were immunized i.p. with 50 g NP-CGG precipitated in Alum.

Cell Preparation and Stimulation

Naïve splenic B cells were purified by negative selection using a biotin conjugated antibody cocktail (CD43, CD4, CD8, CD11b, CD11c, Gr-1, CD138), followed by magnetic bead-depletion of labeled cells (B cell purity ≥ 95%). GC B cells were purified from day 13 to day 14 NP-CGG immunized B1-8i mice or MEG mice. For GC B cell purification from B1-8i mice, biotin conjugated IgD and CD38 antibodies were added to B cell purification cocktail; for GC B cell purification from MEG mice, biotin-CD38 antibody was added to the B cell purification cocktail (GC B cell purity ≥ 90%, example of purity examination by flow cytometry is shown in Figure S5A). Purified B cells and GC B cells were warmed to 37 °C with 5% CO2 in B cell medium (RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine and 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol) for 30min and stimulated with 200ng/ml NP-Ficoll (LGC Biosearch Technologies), 20 μg/ml goat anti-mouse IgM (μ chain specific, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or 20 μg/ml anti-CD40 antibody (FGK45, Bio X Cell or prepared in our lab) as indicated in figure legends. In some experiments, biotinylated anti-CD40 antibody was preincubated with streptavidin at 5:1 molecular ratio, and then used at 2.5 μg/ml to 5 μg/ml for CD40 stimulation. Endotoxin was removed from antibodies used for stimulation with ToxinEraser™ Endotoxin Removal Kit (GenScript) and endotoxin levels were tested with a LAL assay kit (endotoxin < 0.5 EU/ml). Cell viability was determined by LUNA-FL™ Dual Fluorescence Cell Counter (Logos Biosystems) with AO/PI dual staining.

Western Blot Analysis

Whole cell lysates were prepared by direct lysing and boiling samples in Laemmli buffer supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol. The samples were subjected to Western blotting and membranes were incubated with one of the following antibodies: Phospho-IκBα (Ser32; clone: 14D4, Cell Signaling Technology), total-IκBα (clone: L35A5, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-IKKα/IKKβ (Ser176/Ser177; clone: C84E11, Cell Signaling Technology), total-IKKβ (clone: D30C6, Cell Signaling Technology), Actin (clone: C4/actin, BD Biosciences), Phospho-Erk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204; clone: D13.14.4E, Cell Signaling Technology), total-Erk1/2 (clone: 137F5, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536; clone 93H1, Cell Signaling Technology), total- NF-κB-P65 (rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), c-Myc (clone: D84C12, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-Syk (Tyr352; rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology), total-Syk (clone: 5F5, BioLegend), Phospho-Akt (Ser473; clone: D9E, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-S6 (Ser235/236; clone:D57.2.2E, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-FoxO1/FoxO3a (Thr24/Thr32; rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology), total-Foxo1 (clone: C29H4, Cell Signaling Technology), NF-κB2 p100/p52 (rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology). The signals on the membranes were quantitated by ImageJ software. Loading was normalized by Actin blotting.

Flow Cytometry

For surface and intracellular staining, cells were fixed and permeabilized in saponin-based Perm/Wash buffer (Cat#: 554732, BD Biosciences) supplemented with 1.5% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and blocked with Fc receptor antibody (clone: 2.4G2, prepared in the lab) prior to staining with fluorochrome conjugated antibodies: Phospho-Syk (Y352; clone: 17A/P-ZAP70, BD Biosciences), Phospho-S6 (Ser235/236; clone: D57.2.2E, Cell Signaling Technology), Phospho-Akt (pS473; clone: M89-61, BD Biosciences), Phospho-Btk (pY223/Itk pY180; clone: N35-86, BD Biosciences), total-Syk (clone: 5F5, BioLegend), CXCR4 (clone: L276F12, BioLegend), CD86 (clone: GL1, prepared in our lab), B220 (clone: RA3-6B2, BD Bioscience), PNA (Vector Lab), CD38 (clone: 90, prepared in our lab), CD95 (clone: Jo2, BD Biosciences), CD138 (clone: 281-2, BD Biosciences), CD44 (clone: IM7, BioLegend), IgM (goat polyclonal, Jackson ImmunoResearch), Phospho-FoxO1/FoxO3a (Thr24/Thr32; rabbit polyclonal, Cell Signaling Technology).

For transcription factor staining, cells were fixed with 1.5% PFA and then permeabilized in FACS staining buffer (PBS with 3% calf serum, 0.02% sodium azide and 2mM EDTA) containing 0.1% Triton X-100. The following antibodies were used for staining: c-Myc (clone: D84C12, Cell Signaling Technology), IRF4 (clone: IRF4.3E4, Biolegend).

Stained cells were analyzed on an LSRII or Fortessa flow cytometer. Data were analyzed with FlowJo 10 software. Gating strategy for B1-8i or MEG mice: GC B cells were gated on B220+ λ+ PNA+ cells, non-GC B cells were gated on B220+ λ+ PNA− cells and naïve B cells were gated on B220+ λ− PNA− cells. For other mouse models, GC B cells were gated on B220+ PNA+ CD95+ or B220+ PNA+ CD38− cells (naïve B cells: B220+ PNA− CD95− or B220+ PNA− CD38+).

Analysis of Nuclear Translocation of P65, c-Rel, NFAT and Foxo1

Total splenocytes from day 13 to 14 NP-CGG-immunized B1-8i BALB/c or MEG BALB/c mice or day 11 immunized B6 mice were warmed at 37°C for 15 min and then stimulated as indicated in figure legends. Cells were fixed with 1.5% PFA for 10 minutes and permeabilized in FACS staining buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100. Cells were then stained in staining buffer for GC B cell markers (B220, lambda and PNA) and NF-κB-P65 (rabbit polyclonal, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or c-Rel (clone: D4Y6M, Cell Signaling Technology) or NFAT1 (clone: D43B1, Cell Signaling Technology) or Foxo1 (clone: C29H4, Cell Signaling Technology) for 30 minutes. Cells were washed and stained with Cy3- or Alexa 647-conjugated anti-Rabbit secondary antibody (ThermoFisher Scientific) for 10 minutes. Nuclei were stained with DAPI after secondary antibody staining. Data were collected on an Amnis ImageStream®X Mark II Imaging Flow Cytometer and analyzed with IDEAS software using the “Nuclear Localization” feature (EMD Millipore).

For experiments using inhibitors, cells were treated with 2 or 5 μM Syk inhibitor (BAY61-3606, Calbiochem), 10 μM PI3K inhibitor (Ly294002, Calbiochem) or 5 μM Akt1/2 kinase inhibitor (Calbiochem) for 30 min before stimulation.

Specific Deletion of Syk in B cells and in vivo CD40 stimulation

Sykfl/fl hCD20TamCre mice and control Syk+/+ hCD20TamCre mice were gavaged with 1mg Tamoxifen in 100 μl corn oil on Day 8 post NP-CGG immunization and analyzed on Day 11 (3-days post-Tamoxifen). For 4-day Tamoxifen treatment, the mice were gavaged with Tamoxifen at Day 8 and Day 10 post immunization and analyzed on Day 12. The loss of Syk protein was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis with PE conjugated Syk antibody (clone: 5F5, BioLegend).

For in vivo CD40 stimulation: 3 days post Tamoxifen treatment as described above, mice were given intravenously 50 μg CD40 antibody (clone: FGK, Bio X Cell or prepared in our lab) or isotype control (Rat IgG2a, clone 2A3, Bio X Cell). Four hours later, mice were sacrificed and analyzed by flow cytometry for c-Myc.

In Vivo B cell Receptor Stimulation and Analysis

Day 10 NP-CGG immunized IgMi mice were injected intravenously with 400 μg goat anti-mouse IgM (μ chain specific, Jackson ImmunoResearch) or 400 μg goat IgG isotype control (ThermoFisher Scientific). Four hours later, mice were sacrificed and splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry for c-Myc expression and GC B cell LZ and DZ distribution as described above.

Immunofluorescent Histology

Cryostat sections (7 μm) made from OCT (TissueTek)-embedded spleens were fixed and permeabilized in cold acetone, blocked in PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.1% Tween-20, Fc receptor antibody (clone: 2.4G2, prepared in the lab) and 10% rat serum prior to staining with combined antibodies including biotin labeled IgD (clone: 11-26c, Biolegend), Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated PNA (Vector Lab, conjugated in the lab) and Alexa Fluor 647 conjugated CR1 (clone:8C12, prepared in the lab). Alexa Fluor 555 conjugated streptavidin (ThermoFisher Scientific) was used to detect biotin labeled IgD. 40× tiled images of splenic sections were acquired with an IX83 fluorescent microscope (Olympus) and image analysis was performed with cellSens Dimension software (Olympus) with the count and measure module.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed with Prism software (GraphPad Software). P-values were determined using Student’s t-tests (two-tailed). For multiple comparisons, One-Way ANOVA followed by Tukey test was applied. Differences between groups were considered significant for P-values ≤ 0.05 (* P ≤ 0.05; ** P ≤ 0.01; *** P ≤ 0.001; **** P ≤ 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

eTOC Highlights.

In GC B cells, CD40 signals via NF-kB but not PI3K, while BCR does not activate NFk-B

Weak BCR signals in GC B cells propagate to Akt-dependent phosphorylation of Foxo1

In GC B cells both CD40 and BCR signals are required to synergistically induce c-Myc

Combined CD40 and BCR signals induce p-S6 in GC B cells, permitting cell cycle entry

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ari Melnick and Lee Anne Sinha for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Ari Waisman for making available to us the IgMi mice. We thank Bill Hawse for many useful discussions. We thank Laura Conter and Nikita Trivedi for supporting experimental procedures. Supported by NIH grants R01 AI105018 and R01 AI043603.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: Wei Luo, Florian Weisel and Mark Shlomchik designed research, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. Wei Luo carried out all of the experiments.

References

- Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, Chatila T, Conley ME, Cunningham- Rundles C, Etzioni A, Franco JL, Gaspar HB, Holland SM, et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: an update on the classification from the international union of immunological societies expert committee for primary immunodeficiency. Frontiers in immunology. 2014;5:162. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CD, Okada T, Cyster JG. Germinal-center organization and cellular dynamics. Immunity. 2007a;27:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen CD, Okada T, Tang HL, Cyster JG. Imaging of germinal center selection events during affinity maturation. Science. 2007b;315:528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1136736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calado DP, Sasaki Y, Godinho SA, Pellerin A, Kochert K, Sleckman BP, de Alboran IM, Janz M, Rodig S, Rajewsky K. The cell-cycle regulator c-Myc is essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centers. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni.2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho SH, Raybuck AL, Stengel K, Wei M, Beck TC, Volanakis E, Thomas JW, Hiebert S, Haase VH, Boothby MR. Germinal centre hypoxia and regulation of antibody qualities by a hypoxia response system. Nature. 2016;537:234–238. doi: 10.1038/nature19334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Porto JM, Gauld SB, Merrell KT, Mills D, Pugh-Bernard AE, Cambier J. B cell antigen receptor signaling 101. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:599–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV. c-myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Silva NS, Klein U. Dynamics of B cells in germinal centres. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:137–148. doi: 10.1038/nri3804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFranco AL. Germinal centers and autoimmune disease in humans and mice. Immunol Cell Biol. 2016;94:918–924. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Sola D, Kung J, Holmes AB, Wells VA, Mo T, Basso K, Dalla-Favera R. The FOXO1 Transcription Factor Instructs the Germinal Center Dark Zone Program. Immunity. 2015;43:1064–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Sola D, Victora GD, Ying CY, Phan RT, Saito M, Nussenzweig MC, Dalla-Favera R. The proto-oncogene MYC is required for selection in the germinal center and cyclic reentry. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ni.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufner A, Thomas G. Ribosomal S6 kinase signaling and the control of translation. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:100–109. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyao MP, Buckler AJ, Sonenshein GE. Interaction of an NF-kappa B-like factor with a site upstream of the c-myc promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4727–4731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgueta R, Benson MJ, de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Guo Y, Noelle RJ. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:152–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersching J, Efeyan A, Mesin L, Jacobsen JT, Pasqual G, Grabiner BC, Dominguez-Sola D, Sabatini DM, Victora GD. Germinal Center Selection and Affinity Maturation Require Dynamic Regulation of mTORC1 Kinase. Immunity. 2017;46:1045–1058 e1046. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan B, Lim C, Chu G, Hua S, Ding Z, Collins M, Hu J, Jiang S, Fletcher-Sananikone E, Zhuang L, et al. FoxOs enforce a progression checkpoint to constrain mTORC1-activated renal tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:472–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin AD, Shulman Z, Nussenzweig MC. Clonal selection in the germinal centre by regulated proliferation and hypermutation. Nature. 2014;509:637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel KM, Liarski VM, Clark MR. Germinal center B-cells. Autoimmunity. 2012;45:333–347. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2012.665524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum LG, Haberman AM, Anderson SM, Shlomchik MJ. Germinal center initiation, variable gene region hypermutation, and mutant B cell selection without detectable immune complexes on follicular dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:931–942. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser AE, Junt T, Mempel TR, Sneddon MW, Kleinstein SH, Henrickson SE, von Andrian UH, Shlomchik MJ, Haberman AM. Definition of germinal-center B cell migration in vivo reveals predominant intrazonal circulation patterns. Immunity. 2007;26:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel S, Binh Giang T, Kan A, Marchingo JM, Lye BK, Corcoran LM, Hodgkin PD. A Myc-dependent division timer complements a cell-death timer to regulate T cell and B cell responses. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:96–103. doi: 10.1038/ni.3598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise N, De Silva NS, Silva K, Carette A, Simonetti G, Pasparakis M, Klein U. Germinal center B cell maintenance and differentiation are controlled by distinct NF-kappaB transcription factor subunits. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2103–2118. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobeika E, Levit-Zerdoun E, Anastasopoulou V, Pohlmeyer R, Altmeier S, Alsadeq A, Dobenecker MW, Pelanda R, Reth M. CD19 and BAFF-R can signal to promote B-cell survival in the absence of Syk. Embo Journal. 2015;34:925–939. doi: 10.15252/embj.201489732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellusova J, Cato MH, Apgar JR, Ramezani-Rad P, Leung CR, Chen CD, Richardson AD, Conner EM, Benschop RJ, Woodgett JR, Rickert RC. Gsk3 is a metabolic checkpoint regulator in B cells. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:303–312. doi: 10.1038/ni.3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe T, Naka T, Yoshida K, Tanaka T, Fujiwara H, Suematsu S, Yoshida N, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. The immune responses in CD40-deficient mice: impaired immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1994;1:167–178. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil AM, Cambier JC, Shlomchik MJ. B cell receptor signal transduction in the GC is short-circuited by high phosphatase activity. Science. 2012;336:1178–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.1213368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Kim JY, Yu BP, Chung HY. The activation of NF-kappaB through Akt-induced FOXO1 phosphorylation during aging and its modulation by calorie restriction. Biogerontology. 2008;9:33–47. doi: 10.1007/s10522-007-9114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopman G, Keehnen RMJ, Lindhout E, Zhou DFH, deGroot C, Pals ST. Germinal center B cells rescued from apoptosis by CD40 ligation or attachment to follicular dendritic cells, but not by engagement of surface immunoglobulin or adhesion receptors, become resistant to CD95-induced apoptosis. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:1–7. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa FA, Pierce JW, Sonenshein GE. Differential regulation of the c-myc oncogene promoter by the NF-kappa B rel family of transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1039–1044. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Hron JD, Peng SL. Regulation of NF-kappaB, Th activation, and autoinflammation by the forkhead transcription factor Foxo3a. Immunity. 2004;21:203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Xu H, Shih C, Wan Z, Ma X, Ma W, Luo D, Qi H. T-B-cell entanglement and ICOSL-driven feed-forward regulation of germinal centre reaction. Nature. 2015;517:214–218. doi: 10.1038/nature13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YJ, Joshua DE, Williams GT, Smith CA, Gordon J, MacLennan IC. Mechanism of antigen-driven selection in germinal centres. Nature. 1989;342:929–931. doi: 10.1038/342929a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P, Shih C, Qi H. Ephrin B1-mediated repulsion and signaling control germinal center T cell territoriality and function. Science. 2017;356 doi: 10.1126/science.aai9264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer CT, Gazumyan A, Kara EE, Gitlin AD, Golijanin J, Viant C, Pai J, Oliveira TY, Wang Q, Escolano A, et al. The microanatomic segregation of selection by apoptosis in the germinal center. Science. 2017;358 doi: 10.1126/science.aao2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Rothstein TL. B cell receptor (BCR) cross-talk: CD40 engagement creates an alternate pathway for BCR signaling that activates I kappa B kinase/I kappa B alpha/NF-kappa B without the need for PI3K and phospholipase C gamma. J Immunol. 2005;174:6062–6070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.10.6062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J, Matloubian M, Zikherman J. Cutting edge: An in vivo reporter reveals active B cell receptor signaling in the germinal center. J Immunol. 2015;194:2993–2997. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowosad CR, Spillane KM, Tolar P. Germinal center B cells recognize antigen through a specialized immune synapse architecture. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:870–877. doi: 10.1038/ni.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw BR, Fanslow WC, 3rd, Armitage RJ, Campbell KA, Liggitt D, Wright B, Davison BL, Maliszewski CR. Humoral immune responses in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander S, Chu VT, Yasuda T, Franklin A, Graf R, Calado DP, Li S, Imami K, Selbach M, Di Virgilio M, et al. PI3 Kinase and FOXO1 Transcription Factor Activity Differentially Control B Cells in the Germinal Center Light and Dark Zones. Immunity. 2015;43:1075–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwickert TA, Lindquist RL, Shakhar G, Livshits G, Skokos D, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. In vivo imaging of germinal centres reveals a dynamic open structure. Nature. 2007;446:83–87. doi: 10.1038/nature05573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlomchik MJ, Weisel F. Germinal center selection and the development of memory B and plasma cells. Immunological reviews. 2012a;247:52–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shlomchik MJ, Weisel F. Germinal centers. Immunological reviews. 2012b;247:5–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman Z, Gitlin AD, Weinstein JS, Lainez B, Esplugues E, Flavell RA, Craft JE, Nussenzweig MC. Dynamic signaling by T follicular helper cells during germinal center B cell selection. Science. 2014;345:1058–1062. doi: 10.1126/science.1257861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda E, Pewzner-Jung Y, Schwers S, Taki S, Jung S, Eilat D, Rajewsky K. B cell development under the condition of allelic inclusion. Immunity. 1997;6:225–233. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Dutta PR, Cerasoli DM, Kelsoe G. In situ studies of the primary immune response to (4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl)acetyl. V. Affinity maturation develops in two stages of clonal selection. J Exp Med. 1998;187:885–895. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tybulewicz VLJ, Schweighoffer E, Vanes L, Nys J, Cantrell D, McCleary S, Smithers N. The BAFF receptor transduces survival signals by co-opting the B cell receptor signaling pathway. Immunology. 2013;140:8–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzivion G, Dobson M, Ramakrishnan G. FoxO transcription factors; Regulation by AKT and 14-3-3 proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1938–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riggelen J, Yetil A, Felsher DW. MYC as a regulator of ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2010;10:301–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora GD, Dominguez-Sola D, Holmes AB, Deroubaix S, Dalla-Favera R, Nussenzweig MC. Identification of human germinal center light and dark zone cells and their relationship to human B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2012;120:2240–2248. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-415380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Fooksman DR, Kamphorst AO, Meyer-Hermann M, Dustin ML, Nussenzweig MC. Germinal center dynamics revealed by multiphoton microscopy with a photoactivatable fluorescent reporter. Cell. 2010;143:592–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waisman A, Kraus M, Seagal J, Ghosh S, Melamed D, Song JA, Sasaki Y, Classen S, Lutz C, Brombacher F, et al. IgG1 B cell receptor signaling is inhibited by CD22 and promotes the development of B cells whose survival is less dependent on Ig alpha/beta. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204:747–758. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm K, Happel K, Eelen G, Schoors S, Oellerich MF, Lim R, Zimmermann B, Aspalter IM, Franco CA, Boettger T, et al. FOXO1 couples metabolic activity and growth state in the vascular endothelium. Nature. 2016;529:216–U226. doi: 10.1038/nature16498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Foy TM, Laman JD, Elliott EA, Dunn JJ, Waldschmidt TJ, Elsemore J, Noelle RJ, Flavell RA. Mice deficient for the CD40 ligand. Immunity. 1994;1:423–431. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zikherman J, Parameswaran R, Weiss A. Endogenous antigen tunes the responsiveness of naive B cells but not T cells. Nature. 2012;489:160–164. doi: 10.1038/nature11311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.