Abstract

The relation between childhood socioeconomic status (SES) and executive function (EF) has recently attracted attention within psychology, following reports of substantial SES disparities in children’s EF. Adding to the importance of this relation, EF has been proposed as a mediator of socioeconomic disparities in lifelong achievement and health. However, evidence about the relationship between childhood SES and EF is mixed, and there has been no systematic attempt to evaluate this relationship across studies. This meta-analysis systematically reviewed the literature for studies in which samples of children varying in SES were evaluated on EF, including studies with and without primary hypotheses about SES. The analysis included 8,760 children between the ages of 2 and 18 gathered from 25 independent samples. Analyses showed a small but statistically significant correlation between SES and EF across all studies (rrandom = .16, 95% CI [.12, .21]) without correcting for attenuation due to range restriction or measurement unreliability. Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies, and a number of factors, including the amount of SES variability in the sample and the number of EF measures used, emerged as moderators. Using only the 15 studies with meaningful SES variability in the sample, the average correlation between SES and EF was small-to-medium in size (rrandom = .22, 95% CI [.17, .27]). Using only the 6 studies with multiple measures of EF, the relationship was medium in size (rrandom = .28, 95% CI [.18–.37]). In sum, this meta-analysis supports the presence of SES disparities in EF and suggests that they are between small and medium in size, depending on the methods used to measure them.

Executive function (EF) refers to the cognitive processes, supported by prefrontal cortex, that regulate goal-directed behavior (Miller & Cohen, 2001). EF develops throughout childhood and adolescence, with individual differences observed from infancy (e.g., Diamond, 2001) through adulthood (e.g., Miyake & Friedman, 2012). A recently discovered predictor of such differences, documented in a growing literature within psychology and education, is childhood socioeconomic status (SES). SES refers to a combination of economic resources (e.g., income and material wealth) and social resources (e.g., social prestige and education) and correlates with a variety of family characteristics, such as parenting behavior and frequency of stressful life events (e.g., Duncan & Magnuson, 2012).

SES disparities in EF among children have been demonstrated with a wide array of tasks, including Stroop-like tasks, digit span and dimensional card sorting (e.g., Blair et al., 2011; Dilworth-Bart, 2012; Hughes & Ensor, 2005; Mezzacappa, 2004; Sarsour, Sheridan, Jutte, Nuru-Jeter, Hinshaw & Boyce, 2011). Additionally, SES disparities in EF appear larger than disparities in other cognitive abilities. In three studies comparing SES disparities across neurocognitive systems in children, disparities in EF were larger than disparities in most other neurocognitive domains (Farah et al., 2006; Noble, Norman & Farah, 2005; Noble, McCandliss & Farah, 2007). However, not all studies have found SES differences in childhood EF (e.g., Engel, Santos & Gathercole, 2008; Lupien, King, Meaney & McEwen, 2001; Wiebe, Espy & Charak, 2007).

In view of these mixed results, it is possible that SES and EF are only weakly correlated or even that they are uncorrelated, with some combination of publication bias and citation bias leading to the generalization that SES predicts EF. Alternatively, the null results may be explained by small but real correlations combined with chance error, or systematic factors such as stringent exclusionary criteria for health and cognitive ability resulting in exceptionally healthy and able low SES subjects (Hackman, Farah & Meaney, 2010).

Understanding the relationship between SES and EF is important for at least three reasons. First, the basic science of human development involves understanding the nature of individual differences in cognition and their association with developmental contexts. Much research has examined the relation between extreme environmental adversities, such as psychosocial deprivation and abuse (e.g., Pollak et al., 2010; Hostinar, 2012) and the development of cognitive systems, particularly the prefrontal system of executive function. More recently work has begun to examine whether development of neural systems also varies with contexts within the normal range of childhood experience, such as those associated with childhood socioeconomic status. This work frequently identifies EF and its prefrontal substrates as associated with childhood SES (e.g., Kishiyama, Boyce, Jimenez, Perry, & Knight, 2008; Lawson et al., 2013; Sheridan et al., 2012).

Second, at a more practical level, executive function predicts a variety of important life outcomes, including academic achievement (e.g., Best, Miller & Naglieri, 2011), health behaviors (e.g., Williams & Thayer, 2009) and mental health (e.g., Rogers et al., 2004). These outcomes are themselves positively associated with SES. The relevance of assessing the SES-EF relation lies partly in the potential role of EF as a mediator of SES disparities in these outcomes. Indeed, a number of interventions have specifically targeted selective attention or executive function as a means to reducing SES disparities in academic achievement (e.g., Diamond & Lee, 2011; Neville et al., 2013). If the relationship between SES and EF is weak or nonexistent, it is unlikely that EF is a meaningful mediator of SES disparities in cognitive and health outcomes and such interventions would hold less promise.

Third, the relation of SES to EF is of relevance to developmental psychology research more broadly. Even for studies whose hypotheses are unrelated to SES, the SES of participants may affect results and should therefore be considered. The magnitude of the SES-EF relationship will determine how consequential unmeasured or uncontrolled SES would be in such studies.

In addition, because the extant literature on SES and EF is inconsistent, a quantitative synthesis of this literature offers the opportunity to identify study features (e.g., sample population, the measurement of SES or EF) that may help explain when and why SES disparities are found and when and why they are not. The present meta-analysis provides the first quantitative synthesis of studies reporting correlations between SES and EF.

Measuring Socioeconomic Status

The term socioeconomic status (SES) is used to refer to a family’s access to economic and social resources. SES can be estimated with measures of family income, parental education level, or parental occupational prestige. Researchers sometimes combine two or more such measures to estimate overall SES. However, some have argued that components of SES – such as family income and parental education should be examined separately (Braveman et al., 2005; Duncan & Magnuson, 2012; Geyer, Hemström, Peter, & Vågerö, 2006). These researchers note that these components have different degrees of stability across time and are likely to be responsive to different policy interventions (Duncan & Magnuson, 2012). Rather than assume that all measures of SES are equally predictive of EF, or select a particular measure a priori, we take advantage of the full range of SES measures used in the EF literature by including type of SES as a moderator. We are thereby able to examine whether the measures used to estimate child SES influences the magnitude SES-EF relationship.

Here it is worth noting that SES and poverty are distinct, though related, concepts. Poverty corresponds most closely to the lowest end of the SES continuum. Although poverty is a pressing social concern, many important life outcomes including health and academic achievement show a gradient over the full range of SES (e.g., Adler et al., 1994; Reardon, 2011), and the current meta-analysis therefore measures SES continuously across the full range of family income, parental education, and parental occupational prestige.

Although SES is typically measured using the variables just mentioned, these variables need not be the proximal causes of the observed SES disparities. Indeed, it is widely assumed that some combination of factors associated with SES play causal roles, including (but not limited to) parenting practices, exposure to stressors and school or daycare quality. The proximal variables or mediators of the SES-EF relationship is an important topic for research, but it is not the focus of the present meta-analysis. Furthermore, the research summarized by this meta-analysis was not designed to identify specific causes. Therefore, the present meta-analysis is confined to answering questions about the relation of SES and EF, including the moderating effect of how SES is measured, but cannot reveal the specific causal pathways through which SES and EF are associated.

Measuring Executive Function

The measurement of EF is similarly multifactorial, related to the multifactorial nature of EF itself. One prominent framework proposes that EF is composed of three related but separable basic components: updating information in working memory, shifting attention, and inhibiting prepotent responses. According to this model, these three basic components contribute differentially to performance on complex EF tasks (Miyake et al., 2000). Although there is mixed evidence about the extent to which the structure of EF is consistent across development, studies of EF in childhood commonly conceptualize EF tasks in terms of working memory, attention shifting, and inhibition (Best & Miller, 2010). Therefore, the current meta-analysis employed this framework to classify EF tasks, and examined correlations between SES and separate components of EF, as well as overall EF.

Goals of Current Meta-Analysis

The current meta-analysis provides a systematic, quantitative synthesis of existing research, aimed at advancing our knowledge of childhood SES disparities in EF. Specifically, it is intended to answer several key questions. First, is there a relation between SES and EF in typically developing children? Second, how strong is that relation across studies?

The third question concerns the variability among study outcomes: Is it due simply to random error, or is the literature heterogeneous, with studies truly differing in the effect sizes they are capturing? Fourth, to what can any such heterogeneity be attributed? Potential moderators, that is, factors that account for differences in effect sizes, include features of the sample (e.g., mean age, SES variability), and study design (e.g., operationalization of SES and EF). The identification of moderators may help explain disparate findings in the literature.

A special case of the moderator question concerns the hypothesis noted earlier, that different components of SES such as parental education and income may impact EF development differently. This is difficult to assess with individual studies, as few have included multiple measures of SES. However, by combining information from multiple studies, we can begin to estimate separate effect sizes for income-based, education-based, occupation-based and composite SES measures.

The current meta-analysis also advances our understanding by broadening the set of studies brought to bear on these questions about SES disparities in EF. The literature generally cited in this connection is focused specifically on SES and EF. In contrast, a much larger literature exists in which EF has been measured in connection with a wide range of topics, and SES has been measured as a covariate. By meta-analyzing this larger literature, we broaden the population of studies relevant to the topic of SES disparities in EF and also reduce the risk of publication bias affecting our conclusions (Cooper, 2010).

Method

Search Procedures and Selection of Studies

Literature search

Relevant studies were identified through searches of the databases PsycINFO & ERIC through January, 2013 using keywords for executive function and for socioeconomic status. The search required that studies use at least one of the following executive function keywords in the abstract: executive function, cognitive control, executive functioning, self-regulation, working memory, inhibition, inhibitory control, shifting, cognitive flexibility, attention, prefrontal. Identified studies also used at least one of the following socioeconomic status keywords in the entire paper: socioeconomic status, SES, socio-economic status, social status, income, poverty, disadvantaged, parental education. Unpublished dissertations, in addition to published journal articles, were included in order to minimize the effects of publication bias. This search identified a total of 2711 results, which were screened for the inclusion criteria. An additional 19 potentially relevant studies were identified by reviewing the citations of articles identified in this search and by searching the work of relevant researchers.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the meta-analysis, studies were required to meet the following inclusion criteria:

Published or unpublished empirical paper

Was written between 1980 and January, 2013

Includes at least one measure of a behavioral, neurocognitive task of executive function (EF)

Includes at least one variable, from the following list, as a measure of socioeconomic status (SES): income, parental education, parental occupation, or some combination of these measures

Uses a sample of children who were between the ages of 2 and 18, at one or more time-point when data are reported

The population was not selected for any physical or mental disorder (e.g., ADHD, depression, low birth weight) or special condition (e.g., bilingualism, homelessness) present in the children or the parents

The population represented a continuous distribution of socioeconomic status

One or more zero-order Pearson correlations between EF and SES variables were reported in the paper or could be obtained from the corresponding author

Eligible EF and SES Measures

Executive function can be measured in a number of ways, including performance on neurocognitive tasks, self-report questionnaires, and informant-report questionnaires (Hughes, 2011). For the purpose of this meta-analysis, studies were considered eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis only when they included at least one behavioral task measure of executive function. Eligible tasks included measures of working memory (e.g., Digit Span tasks), attention shifting (e.g., Dimensional Change Card Sort tasks), inhibition (e.g., Stroop tasks) and other tasks commonly classified as executive function (e.g., Tower of Hanoi, Continuous Performance tasks). Studies that reported only questionnaire measures of executive function or delay-of-gratification measures were not eligible for inclusion.

Similarly, a number of measures are commonly used to assess socioeconomic status. As already noted, most definitions of SES conceptualize it as a combination of family income, parental education, and parental occupation (Duncan & Magnuson, 2012). Therefore, studies were considered eligible for inclusion only when they included at least one variable that is a measure of family-level SES: family income (e.g., household income, income-to-needs ratio), parental education (e.g., maternal education, paternal education), or parental occupation (e.g., maternal occupation, paternal occupation). Composite SES measures including two or more of the aforementioned measures, including those that also included a measure of family wealth, were eligible for inclusion. Studies that reported only other measures of SES (e.g., neighborhood disadvantage, participation in free or reduced lunch, amount of time spent in poverty) or of related sociodemographic risk factors (e.g., single-parent households) were not eligible for inclusion. Also excluded were studies that mention aspects of the sample’s SES, (e.g., the proportion of the sample below the poverty line) but do not identify an SES variable of interest or a covariate and thus cannot provide information about the SES-EF relation.

SES distribution

Meta-analysis requires identifying a common effect size statistic with which to compile results across studies. Which effect size statistic is appropriate depends on the hypotheses being tested by the meta-analysis and the nature of the variables being analyzed (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Because the majority of identified papers, including those that did not have primary hypotheses about SES, used samples with continuous SES distributions, Pearson correlations were used as the effect size measure in the present meta-analysis.

Studies comparing children from “higher SES” or “lower SES” groups, drawn from a continuous SES distribution, were included when enough information was reported or obtained from study authors to estimate r-type effect sizes. Mean difference-type effect sizes were converted to r-type effect sizes.

In contrast, extreme group designs, in which children are enrolled based on having an SES below a relatively low SES threshold or above a different and relatively higher threshold, yield effect sizes that are not comparable to each other or to the others included here. Following recommendations that it is inappropriate to apply meta-analysis to effect size estimates based on extreme groups data (Preacher et al., 2005), we excluded such studies.

Selection of studies

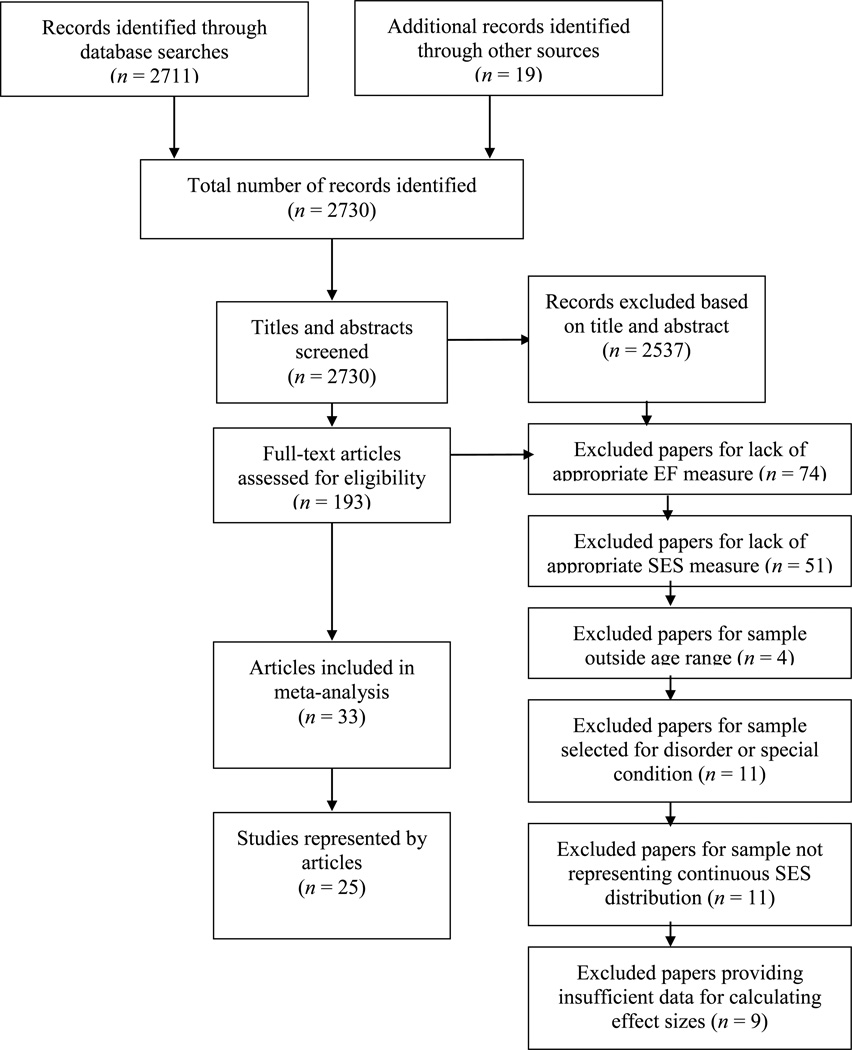

A flow chart depicting the search process and exclusion of studies is shown in Figure 1. After the initial search, all of the titles and abstracts were screened to eliminate articles that, based on the title and abstract alone, did not meet inclusion criteria (e.g., not an empirical paper, published outside the relevant time period, not about the relevant constructs), resulting in 193 articles identified as potentially relevant. The full text of these potentially-relevant articles were reviewed to determine eligibility according to the following screening criteria: appropriate EF measure, appropriate SES measure, subjects within relevant age range, population not selected for any disorder or special condition, population represented continuous SES distribution. 42 articles met these inclusion criteria. To assess the reliability of this screening process, 36 articles (approximately 18.6%) were screened by two individuals, which yielded a Kappa of .83, which is considered “almost perfect” agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating the identification of included studies.

These 42 articles were then screened to determine whether they reported one or more correlations between SES variables and EF variables in the article, or reported enough information for at least one correlation to be calculated. The corresponding authors of articles that did not report enough information to calculate an r-type effect size for unique samples were contacted to request this information. Of the 42 articles that met inclusion criteria, 25 articles reported one or more correlations between SES variables and EF variables. Additionally, correlations were received by email for 8 articles. 9 articles were excluded because they did not report the relevant correlations or provide them by email. Thus, 33 articles, representing 25 datasets, were eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

Effect Size and Moderator Coding Procedure

All articles were coded for effect sizes and moderators using a formal coding manual, and the first author made all final coding decisions. Additionally, a research assistant was trained on the coding procedure and coded moderators and effect sizes for 94% of articles. Inter-rater reliability analyses were performed to determine consistency among raters. Kappa statistics are reported for nominal moderators. Based on Landis & Koch’s (1977) guidelines, Kappa values of .81–1.0 were considered “almost perfect agreement,” and Kappa values of .61–.80 were considered “substantial agreement.” Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) statistics are reported for effect size information (e.g., Pearson’s r’s and sample sizes) and continuous or interval level moderators (e.g., mean age). Based on Fleiss’s (1986) guidelines, values of ICC above .75 were taken to represent “excellent” reliability.

Effect Size coding

Pearson correlations and samples sizes were recorded for each correlation between SES measures and EF measures reported in each article. Pearson correlations were reverse coded as appropriate (e.g., in cases where a higher score on the EF variable indicates worse performance, or a higher score on the SES variable indicates lower SES) such that a positive correlation indicated a that higher SES is associated with better EF. Sample sizes were recorded as reported for each effect size, or were estimated as needed using reported information about total sample size and percentage of missing data. The interrator reliability for the raters on Pearson correlations was ICC (3,1) = .92, and the interrator reliability on sample sizes for all coded effect sizes was ICC (3,1) = .98.

Moderator coding

Following Lipsey and Wilson (2001), moderators are organized based on whether they are characteristics of the sample (e.g., sample age, gender composition) or of the measures of SES or EF used to estimate the effect size. Sample characteristics should be the same for all correlations within the sample, whereas effect size characteristics may vary for different correlations reported within the same sample (e.g., a study reporting a correlation for income-EF and a separate correlation for parental education-EF). Additionally, we include two potential moderators related to publication characteristics because they could vary between different publications from the same study.

Sample characteristics

Five characteristics of the sample were coded for each sample using information from all published and unpublished papers included in the meta-analysis. In all cases, when information about a particular sample characteristic was not reported in any publications about the sample, that sample characteristic was coded as Not Reported and the study was excluded from the appropriate moderator analysis. Additionally, in cases where multiple publications from the same study received different codes for a moderator variable, the study was excluded from the appropriate moderator analysis.

Age range

The range between the youngest and oldest participant in the study was coded in the following categories: < 2 years, 2 – 3.99 years, 4 – 6.99 years, > 7 years. The interrater reliability on this variable was Kappa = .81 (p < .001).

Intended sample SES

The SES distribution of the intended sample, as described by the paper(s), was coded into the following nominal categories: Low SES (e.g., studies with the stated goal of recruiting a low-SES or “at risk” sample, samples recruited from Head Start), Middle SES (e.g., studies with the stated goal of recruiting a middle-SES sample), High SES (e.g., studies with the stated goal of recruiting a high-SES sample), Representative/Diverse (e.g., studies with the stated goal of recruiting subjects of diverse SES), Convenience Sample (e.g., studies with no stated goal of recruiting a particular SES range). The interrater reliability on this variable was Kappa = .71 (p < .001).

Amount of SES variability in the sample

The SES variability of the sample was coded into two categories: Meaningful Variability Reported and Meaningful Variability Not Reported. We were not able to use a specific threshold to make this coding decision because the information that papers reported regarding sample variability was not consistent across papers. Instead, studies were categorized as ‘Meaningful Variability Reported’ when the paper described the sample as heterogeneous or reported a substantial amount of SES variability in the sample, and were categorized as ‘Meaningful Variability Not Reported’ when the paper described the sample as homogenous (e.g., “a sample of middle-socioeconomic status kindergartners” as in Cameron et al., 2012), reported a small amount of SES variability in the sample (e.g., a sample in which the standard deviation for family income is under $7,000 and only 14.2% of caregivers are classified as having an associates or bachelors degree as in Rhoades, Greenberg & Domitrovich, 2009) or did not include a description of the SES variability of the sample. The interrater reliability on this variable was Kappa = .75 (p =.001). The information used to make this coding decision for each independent sample is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

For each independent sample, the coding decision about whether meaningful SES variability was reported, the information used to determine this, and the page number of this information is shown

| Study | Meaningful SES variability reported? |

Information used to determine amount of SES variability | Page |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Berry, D., Blair, C., Willoughby, M., Granger, D., & The Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2012). & Blair, C., et al. (2011). |

YES | Blair et al. (2011): Table 1 | Blair et al. (2011): 1976 |

|

Cameron, C. et al (2012) & McClelland et al. (2007) |

Cameron et al., 2012: NO McClelland et al., 2007: YES; Therefore Excluded |

Cameron et al. (2012): “This study examined the contribution of executive function (EF) and multiple aspects of fine motor skills to achievement on 6 standardized assessments in a sample of middle- socioeconomic status kindergarteners.” McClelland et al. (2007): “Children were recruited from two sites: a predominantly middle to upper-middle-SES urban fringe area with a range of economic and ethnic diversity in Michigan, and a mixed-SES rural site in Oregon.” |

Cameron et al. (2012): 1233 McClelland et al. (2007): 950 |

| De Jong, P. F. (1993) | NO | Not Reported | |

|

Deng, M. (2008). & Turner, K.A., (2010). |

YES |

Deng (2008): “Participants (206 families) were recruited at 3 months of child age for the Durham Child Heath and Development (DCHD) Study. Distributed across levels of income and education, these families came from the greater Durham area in North Carolina, and were specifically recruited to represent an approximately equal number of European and African American families. Formal education among the participating mothers varied widely, with 14% 24 having no high school degree, 18% having a high school diploma or G.E.D., 22% with some college or vocational school experience, 29% with a four-year bachelor’s degree, and 17% having received education beyond a bachelor degree.” Turner (2010): “At the 60-month visit, family income-to-needs ratios ranged from 0.05 to 24.33 with an average of 4.41 (SD = 3.39). Mother’s years of education for the sample ranged from 5 to 20 years with an average of 15.09 (2.61) years or at least some college education.” |

Deng (2008): 23–24 Turner (2010): 10 |

| Deprince, A.P., Winzierl, K.M., & Combs, M.D. (2009). | NO | Not Reported | |

|

Dilworth-Bart, J.E , Khurshid, A., Lowe Vandell, D., (2007). & Jacobson, L., (2008) & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2005). |

YES | Dilworth-Bart et al. (2008): “On average, mothers attained some college level education by the participant child’s birth (mean = 14:26; S:D: = 2:50; range = 7221).”; Income-to-need data from 1, 6, 15 and 24 months were averaged for this analysis (mean = 3:29; S:D: = 2:26; range = 0:09– 19.29).” Jacobson (2008): “On average, mothers had 14.44 years of education, with a range of 7 to 21 years. Although this sample generally consisted of well educated mothers, 71 (7.7%) of the mothers did not finish high school. The average family income-to-needs ratio (based on US census definitions for poverty levels) for this sample was 3.45, with a range from .02 to 23.68” NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2005): “Data from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development were used to address the research questions raised above. The NICHD study is a prospective longitudinal study of a large, geographically, ethnically, and economically diverse sample of children born in 1991 and their families.” |

Dilworth-Bart et al. (2008) Jacobson (2008): 45 NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2005): 101 |

| Dilworth-Bart, J.E., (2012). | YES | “Mean household income was $55,911.08 (SD = 43,125.56); Four (8.2%) mothers completed some high school, 13 (26.5) obtained a high school diploma or equivalent, six (12.2%) obtained a trade or vocational degree, 19 (38.8%) obtained a bachelor’s or associate’s degree, and seven (14.3%) obtained a graduate or professional degree.” |

418 |

| Doan, S.N. & Evans, G.W. (2011). | YES | Table 2 | 18 |

| Fernald, L. et al. (2011). | YES | Table 1 | 837 |

| Hackman, D.A. (2012). Chapter 2. | YES | Table 2 reports parental education (range for primary caregiver: 3–25 years) |

114 |

| Henning, A., Spinath, F.M., Aschersleben, G. (2010). | NO | Not Reported | |

| Ivrendi, A. (2011) | YES | “With respect to parent income, 22 (31%) of them were from a low- income level (699 TL and below), 26 (36.6%) of them from a mid- income level (700–1999TL), and 23 (32.4%) of them from a high-income level (2000 TL and above).” |

241–242 |

| Kegel, C.A. & Bus, A.G. (2012). | NO | “Participants were 312 kindergartners (60% male) from 15 Dutch schools in Rotterdam, Leiden, and the surrounding areas. Schools were selected for inclusion if they served large numbers of low-SES families and agreed to participate. For 70% of the mothers in our sample, their highest level of education was senior secondary vocational education (about 13 years of education, excluding prekindergarten).” |

184 |

| Knipe, H., (2009). | NO | Not Reported | |

| Li-Grining, C. (2005) | NO | Table 2.1 | 42 |

| *Matte-Gangé, C. & Bernier, A. (2011). & Bernier et al. (2012) | YES |

Matte-Gangé & Bernier (2011): “Family income varied from less than $20,000 CDN to more than $100,000 CDN, with an average of $70,000 CDN. Mothers were predominantly Caucasian (86% of sample) and French speaking (79% of sample). They were between 24 and 45 years old (M = 31.2). They had between 10 and 18 years of formal education (M = 15), and 55.8% had a college degree.” |

Matte-Gangé & Bernier (2011): 614 |

|

Mezzacappa, E., Buckner, J.C., & Earls, F. (2011) & Mezzacappa, E. (2004). |

YES |

Mezzacappa et al. (2011): “Participants were 249 children (47% female; 54% Hispanic, 24% African-American, 22% Caucasian) from a Mezzacappa et al. (2011): “Participants were 249 children (47% female; 54% Hispanic, 24% African-American, 22% Caucasian) from a wide range of SES backgrounds who were followed from infancy in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN)” |

Mezzacappa et al. (2011): 883 |

| Noble, K.G., McCandliss, B.D., & Farah, M.J. (2007). | YES | “…the mean income-to-needs ratio in our sample of 130 parents who provided this information was 3.36 (SD 3.78); however, whereas the minimum ratio was only 0.23 (less than one standard deviation from the mean), the maximum was 19.5 (over 4 standard deviations from the mean).” |

469 |

| Phillipson, S. (2009) | YES | Figure 1 | 455 |

| Pinard, F. (2011). | YES | “The sample represented a diverse socioeconomic status background. Scores on the Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status ranged from 14 to 66 (M = 39.15, SD = 15.08)”; Table 2 (Caregiver’s Educational Level); The total household yearly income for the current sample ranged from “earns no income/dependent on welfare” to “earns over $100,000” |

48–49 |

| Raver, C.C., McCoy, D.C., Lowenstein, A.L., & Pess, R. (2012). | NO | “Children resided in families with an average income-to-needs ratio in elementary school of 0.83 (SD = 0.76), indicating that the majority of children in this sample came from families whose annual income and family size placed them below the federal poverty line (which is equal to 1.00).”; Table 1 |

397–398 |

| Rhoades, B., Greenberg, M., & Domitrovich, C. (2009). | NO | Table 1 | 313 |

| Rhoades, B., Warren, H. K., Domitrovich, C. E., & Greenberg M. T. (2011). | NO | “The data for the present study come from an economically disadvantaged sample of children (n = 341) in a public preschool program in an urban school district in the Northeastern United States across three years.”; Table 1 |

184 |

|

Sarsour, K., Sheridan, M., Jutte, D., Nuru-Jeter, A., Hinshaw, S., & Boyce, W.T., (2011). & Sarsour, K. S. (2007). |

YES |

Sarsour et al. (2011): “A community sample of 60 families (from a wide spectrum of socioeconomic backgrounds) was recruited from the San Francisco Bay Area…” |

Sarsour et al. (2011): 122 |

| Wiebe, S.A., Espy, K.A., Charak, D. (2008). | YES | “The average maternal education of the sample was 14 years 1 month (SD 2 years 3 months; range: 8 years to 20 years).” |

577 |

Extent of exclusionary criteria

Studies were also coded for the extent to which the sample selection used exclusionary criteria based on physical health, mental health, and/or cognitive ability that required participants to be healthy or high functioning. Stringent criteria would be expected to attenuate an SES effect (Hackman, Farah & Meaney, 2010). They were coded into two categories: Minimal (e.g., no exclusionary criteria based on health or ability, or criteria that excluded only extreme cases, such as children with mental retardation), and High (e.g., one or more exclusionary criterion based on health or ability, excluding more than extreme cases). The interrater reliability for the raters on this variable was Kappa = .60 (p < .001).

Racial/ethnic composition

The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was coded categorically, based on which racial/ethnic group (e.g., White, Black, Hispanic, Other) predominated (i.e., composed greater than 60% of the sample), or whether the sample was mixed (such that no group composed greater than 60% of the sample). If this information was not reported, the sample was coded as Not Reported.

Mean age

The mean age (in years) of the sample at the time when the EF variable(s) used to obtain effect sizes were collected was coded. When effect sizes from multiple time-points were reported, the mean ages at these time-points were averaged. The interrater reliability for the coders on this variable was found to be ICC (3,1) = .95 (p < .001).

Sex composition

Studies were coded for the percentage of the sample that was male. When multiple publications from the same sample had different sex compositions, the average was used in analyses. The interrater reliability for the coders on this variable was found to be ICC (3,1) = 1 (p < .001).

Effect size characteristics

Four effect size characteristics were coded for each reported correlation between an SES variable an EF variable.

Category of SES construct

For each effect size, the category of the SES construct was coded into the following nominal categories: income-based constructs (e.g., family income, income-to-needs ratio), education-based constructs (e.g., maternal education, paternal education), occupation-based constructs (e.g., maternal occupation, paternal occupation), composite constructs (e.g., constructs using two or three of the aforementioned constructs). The interrater reliability on this variable was Kappa = 1.0 (p < .001).

Number of measures used to calculate the SES variable

For each effect size, the number of measures used to obtain the SES variable was coded. The interrater reliability for the coders on this variable was found to be ICC (3,1) = .98 (p < .001).

Category of EF construct

For each effect size, the category of the EF construct was coded in the following categories: working memory, attention shifting, inhibition, composite or latent variables using 2 or 3 of the aforementioned categories, or other (e.g., planning). The interrater reliability on this variable was Kappa = .95 (p < .001).

Number of measures used to calculate the EF variable

For each effect size, the number of measures used to obtain the EF variable was coded. The interrater reliability for the coders on this variable was found to be ICC (3,1) = .85 (p < .001).

Publication characteristics

Two publication characteristics were coded for each publication.

Type of publication

The article was coded as either a published journal article or an unpublished thesis or doctoral dissertation. By definition, publication bias will influence results obtained from published, but not unpublished, studies. The interrater reliability for the raters on this variable was Kappa = 1.0 (p < .001).

SES as a primary focus

Some studies were undertaken with an interest in the SES-EF relation, whereas others used SES as a covariate in a study of EF. One would expect SES effects to be larger in the first case, in part because such studies might invest more care in the measurement of SES and in addition because such studies would be subject to a bias against publishing small or nonexistent effects of SES. To examine this possibility, the focus of each paper was coded into two categories: SES as a Primary Focus and SES Not as a Primary Focus. Papers were classified as ‘SES as a Primary Focus’ when hypotheses or study goals pertaining to SES were stated in the abstract or introduction of the paper. Papers were classified as ‘SES Not as a Primary Focus’ when hypotheses or study goals about SES were not stated in the abstract or introduction of the paper.

The interrater reliability for the raters on this variable was Kappa = .75 (p < .001).

Analytical Procedures

Transformations, calculations of weighed mean effect sizes, tests for heterogeneity, and moderator analyses were conducted in Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (V.3.3.070, November 2014, Biostat, Englewood-USA).

Calculating average effect sizes

The Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient r was the primary effect size measure used in analyses. Because the product-moment correlation has a problematic standard error formulation in its standard form (Alexander, Scozzaro, & Borodkin, 1989), the correlations were transformed using Fisher’s Zr-transform (Hedges & Olkin, 1985.

Following the recommendations of Hedges & Olkin (1985), each effect size was then weighted by its inverse variance weight in order to account for its precision. This weighting procedure gives greater weight to larger samples than smaller samples (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). For ease of interpretation, Fisher’s Zr-transformed correlations were transformed back into the standard correlational form for the presentation of results.

Statistical independence

Meta-analysis assumes that observations used in analyses are independent of each other. Several steps were taken in order to meet this assumption. First, datasets, rather than publications, were used as the unit of analysis. In cases where multiple articles represented the same datasets (e.g., multiple dissertations and published papers using data from the Family Life Project), effect sizes were averaged across all reported effect sizes from all included articles to generate one effect size per dataset. Papers with partially overlapping samples were also treated as the same dataset. Additionally, many studies included in the meta-analysis reported multiple correlation coefficients based on a single sample. In order to avoid violations of statistical independence, multiple correlations per dataset were averaged, such that each dataset only contributed one effect size to the calculation of the average effect size and to tests of moderation by study and publication characteristics.

Fixed and random effects models

There is ongoing disagreement about whether it is more appropriate to use fixed or random effects model in meta-analysis (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Fixed effects models assume that there is a common true effect size across studies, with random error that stems only from subject-level sampling error in each study. In contrast, random effects models assume that the true effect size varies across studies, due to systematic variability across studies, in addition to subject-level sampling error. Unlike fixed effects models, random effects models allow the results to be generalized to studies not included in the analysis (Borenstein et al., 2009). Because meaningful variation in effect sizes between studies was anticipated, random effects models were deemed most appropriate for the overall analysis and mixed effects were considered most appropriate for moderator analyses. For the sake of comparison, results of the overall analysis and moderator analyses are also reported using fixed effects models.

Tests for heterogeneity

The heterogeneity among effect sizes was examined using the Q statistic and the I2 statistic. The Q statistic provides a significance test indicating whether the observed range of effect sizes is larger than would be expected from within-study variance alone However, the Q statistic has low power to detect true heterogeneity, especially in situations where a small number of studies are included in the meta-analysis (Hardy & Thompson, 1998). Therefore, the I2 index was also used to examine heterogeneity among studies. The I2 index ranges from 0 to 100 and describes the percentage of total variance that is attributed to between-study variance. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% have been used as benchmarks representing low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, 2003).

Moderator analyses

Mean sample age, number of SES measures, and number of EF measures were assessed using meta-regression with random effects. All other moderators were were categorical and thus assessed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) of mixed-effects models for each potential moderator. For the sake of comparison, moderators were also assessed with the Qb test using fixed-effects models.

It is worth noting that many studies reported effect sizes representing multiple levels of a given effect size characteristic (e.g., EF-family income and EF-parental education correlations reported by a single study). This required consideration when testing for moderation by categorical effect size characteristics (e.g., category of SES construct, category of EF construct). The primary analyses used a “shifting units of analysis” approach (Cooper, 2010), which allowed each study to contribute one effect size per level of the effect size characteristic being tested in a given moderation analysis. This approach slightly relaxes assumptions of independence, but allows more data to be utilized in tests of moderation. Studies for which moderator variables could not be coded from the information provided in the study and subgroups including only one study were excluded from moderator analyses.

Tests for publication bias

Several methods were used to assess for publication bias. First, we created funnel plots. The effect size for each dataset was plotted against the study precision (inverse of standard error). The lower the precision of studies, the greater the dispersion of effect sizes around the true value, making the shape of the scatterplot like an upside down funnel. If publication bias has caused nonsignificant small effects to go unreported, then the funnel plot will be negatively skewed, with missing points in the lower left part of the plot (Sterne, Becker & Egger, 2005). In addition, Duval and Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill procedure was used to impute missing studies and compute the summary effect size correcting for the number and assumed location of the missing studies. The classic fail-safe N value was also computed to determine the number of missing studies that would bring the p value above .05, and this value was compared to Rosenthal’s tolerance level for an unlikely number of nonsignificant studies (computed as 5K + 10, where K is the number of observed studies; Rosenthal, 1979). Additionally, Orwin’s fail-safe N value (Orwin, 1983) was computed to determine the number of missing studies that would bring the Fisher’s Z score to a trivial effect size. It is important to note that funnel plots and the trim-and-fill procedure rely on the assumption of homogeneity of effect sizes (Terrin et al., 2003). Therefore, results from these techniques should be interpreted with caution in heterogeneous data sets.

Results

Study characteristics

Table 2 displays characteristics of the papers used in this analysis. There were 33 papers representing 25 independent samples. 18 of the 25 studies took place in the United States; other studies took place in Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Hong Kong, Turkey, and Madagascar. A total of 111 effect sizes were coded from these studies. Individual correlations between SES variables and EF variables ranged from −.11 to .48. Table 3 displays average effect size information for each independent sample, with average correlations ranging from −.04 to .47. According to convention (Cohen, 1988) correlations of .1, .3 and .5 are considered small, medium and large, respectively.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the papers (published and unpublished manuscripts) used in the meta-analysis.

| Publication |

N (total sample) |

Country | % Male |

Predomin ant Race |

Age range |

Mean age |

Intended sample SES |

Meaningful SES variability reported? |

Extent of exclusionary criteria |

Type of publication |

SES as a focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bernier, A., Carlson, S., Deschênes, M., & Matte-Gagné, C. (2012). 1 | 62 | Canada | 38.70 | WHITE | <2 | 3.08 | CONV | YES | HIGH | PUB | YES |

| Berry, D., Blair, C., Willoughby, M., Granger, D., & The Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2012). 2 | 1292 | USA | NR | MIXED | <2 | 3 | LOW | YES | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Blair, C., et al. (2011). 2 | 1292 | USA | NR | MIXED | <2 | 3 | LOW | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Cameron, C. et al (2012). 3 | 213 | USA | 47.00 | MIXED | <2 | 5.82 | CONV | NO | MIN | PUB | NO |

| De Jong, P. F. (1993) | 376 | NETHER LANDS |

NR | WHITE | <2 | 9 | CONV | NO | NR | PUB | NO |

| Deng, M. (2008). 4 | 206 | USA | 51.50 | MIXED | <2 | 3 | REP | YES | NR | UNPUB | NO |

| Deprince, A.P., Winzierl, K.M., & Combs, M.D. (2009). | 114 | USA | 42.00 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 10.39 | CONV | NO | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Dilworth-Bart, J.E., (2012). | 49 | USA | 53.06 | WHITE | <2 | 5 | CONV | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Dilworth-Bart, J.E., Khurshid, A., Lowe Vandell, D., (2007). 5 | 1273 | USA | 52.00 | WHITE | <2 | 4.33 | REP | YES | HIGH | PUB | YES |

| Doan, S.N. & Evans, G.W. (2011). | 342 | USA | NR | WHITE | NR | 17.29 | LOW | YES | NR | PUB | NO |

| Fernald, L. et al. (2011). | 1332 | MADAGASCAR | 47.60 | NR | 2–3.99 | 4.55 | REP | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Hackman, D.A. (2012). Chapter 2. | 316 | USA | 45.90 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 13.52 | REP | YES | HIGH | UNPUB | YES |

| Henning, A., Spinath, F.M., Aschersleben, G. (2010). | 195 | GERMANY | 48.70 | NR | 2–3.99 | 4.92 | CONV | NO | HIGH | PUB | NO |

| Ivrendi, A. (2011) | 71 | TURKEY | 50.70 | NR | <2 | 6.0 | CONV | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Jacobson, L., (2008). 5 | 925 | USA | 48.50 | WHITE | <2 | 8.33 | REP | YES | HIGH | UNPUB | NO |

| Kegel, C.A. & Bus, A.G. (2012). | 312 | NETHE RLANDS |

60.00 | NR | <2 | 4.4 | LOW | NO | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Knipe, H., (2009). | 132 | USA | 40.90 | WHITE | 2–3.99 | 8.95 | CONV | NO | MIN | UNPUB | NO |

| Li-Grining, C. P. (2005) | 439 | USA | 55.00 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 4.50 | LOW | NO | MIN | UNPUB | YES |

| Matte-Gagné, C. & Bernier, A. (2011). 1 | 53 | CANADA | 35.80 | WHITE | <2 | 3.08 | CONV | YES | HIGH | PUB | NO |

| McClelland, M. M. et al. (2007). 3 | 310 | USA | 51.3 | WHITE | <2 | 4.71 | CONV | YES | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Mezzacappa, E. (2004).6 | 249 | USA | 52.60 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 5.96 | REP | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Mezzacappa, E., Buckner, J.C., & Earls, F. (2011).6 | 249 | USA | 52.60 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 6.41 | REP | YES | MIN | PUB | NO |

| NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2005). 5 | 727 | USA | 50.60 | WHITE | <2 | 6.98 | REP | YES | HIGH | PUB | NO |

| Noble, K.G., McCandliss, B.D., & Farah, M.J. (2007). | 168 | USA | 53.30 | MIXED | <2 | 6.5 | REP | YES | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Phillipson, S. (2009) | 215 | HONG KONG |

47.90 | NR | 4–6.99 | 10.70 | CONV | YES | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Pinard, F. (2012). | 138 | USA | 50.70 | MIXED | 2–3.99 | 4.03 | LOW | YES | MIN | UNPUB | YES |

| Raver, C.C., McCoy, D.C., Lowenstein, A.L., & Pess, R. (2012). | 391 | USA | 45.50 | BLACK | 2–3.99 | 4.2 | LOW | NO | MIN | PUB | YES |

| Rhoades, B. (2011). | 341 | USA | 47.00 | BLACK | <2 | 5.67 | LOW | NO | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Rhoades, B., Greenberg, M., & Domitrovich, C. (2009). | 146 | USA | 46.00 | MIXED | <2 | 4.5 | LOW | NO | MIN | PUB | NO |

| Sarsour, K. S. (2007).7 | 60 | USA | 31.70 | MIXED | 4–6.99 | 9.9 | REP | HIGH | UNPUB | YES | |

| Sarsour, K., Sheridan, M., Jutte, D., Nuru-Jeter, A., Hinshaw, S., & Boyce, W.T., (2011) 7 | 60 | USA | 31.70 | MIXED | 4–6.99 | 9.9 | REP | YES | HIGH | PUB | YES |

| Turner, K.A., (2010). 4 | 138 | USA | 47.10 | MIXED | <2 | 5 | REP | YES | NR | UNPUB | YES |

| Wiebe, S.A., Espy, K.A., & Charak, D. (2007). | 243 | USA | 44.40 | WHITE | 2–3.99 | 3.92 | CONV | YES | MIN | PUB | NO |

Note. NR = not reported; WHITE = > 60% of the sample identified as ‘White;’ BLACK = >60% of the sample identified as ‘Black;’ MIXED = no single racial or ethnic group made up > 60% of the sample; CONV = convenience sample, REP = representative or diverse sample, LOW = predominantly low-SES sample, MIN = minimal health- and performance-based exclusionary criteria; HIGH = high health- and performance-based exclusionary criteria

Table 3.

Effect size information for the samples used in the meta-analysis

| Study | SES constructs | EF constructs | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ES reported |

Pearson’s r (Average) |

N (Average) | SES measures | EF measures | Edu | Inc | Occ | SES | WM | AS | In | EF | Other | |

|

Bernier, A., Carlson, S., Deschênes, M., & Matte-Gagné, C. (2012). & Matte-Gange, C. & Bernier, A. (2011). |

1 | .38 | 57.5 | SES composite from: Maternal education, Paternal education, Family income |

Day/Night, Dimensional Change Card Sort, Bear/Dragon |

x | x | |||||||

|

Berry, D., Blair, C., Willoughby, M., Granger, D., & The Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2012). & Blair, C., et al. (2011). |

4 | .35 | 1121 | Income-to-needs, maternal education, caregiver education |

EF composite from: Item selection attention shifting, Spatial Conflict inhibitory control, span-like working memory task |

x | x | x | ||||||

|

Cameron, C. et al (2012). & McClelland et al. (2007). |

4 | .11 | 242.5 | Maternal education; Parental education |

Heads-Shoulders- Knees-Toes, Head- to-Toes Task |

x | x | |||||||

| De Jong, P. F. (1993) | 9 | .08 | 376 | Maternal education, paternal education, Paternal occupation |

Digit Span, Star Counting, Syllable Counting |

x | x | x | x | |||||

|

Deng, M. (2008). & Turner, K.A., (2010). |

9 | .16 | 138 | Maternal education, Income-to-needs ratio |

Flexible Item Selection Task, Day/Night, backwards Digit Span, |

x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Deprince, A.P., Winzierl, K.M., & Combs, M.D. (2009). | 1 | .20 | 110 | Hollingshead occupational prestige, Parental education, parental occupation |

WISC arithmetic, letter-number sequencing, & digit span, symbol search, Gordon Diagnostic System, Stroop task |

x | x | |||||||

|

Dilworth-Bart, J.E , Khurshid, A., Lowe Vandell, D., (2007). & Jacobson, L., (2008) & NICHD Early Child Care Research Network (2005). |

9 | .19 | 857 | Family income, maternal education, income-to-needs, income category |

Continuous Performance Test, Day/Night, WJ-R Memory for Sentences, Tower of Hanoi, Delay of gratification |

x | x | x | x | |||||

| Dilworth-Bart, J.E., (2012). | 12 | .36 | 49 | Maternal education, Household income, SES |

Peg-tapping, Fish Flanker, Stanford- Binet verbal & non-verbal working memory |

x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Doan, S.N. & Evans, G.W. (2011). | 1 | .14 | 214 | Poverty | Working memory (spatial task) |

x | x | |||||||

| Fernald, L. et al. (2011). | 4 | .18 | 1064 | Maternal education, paternal education |

Working Memory, Leiter-Revised Attention Sustained Task |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Hackman, D.A. (2012). Chapter 2. | 7 | .14 | 314 | Parental education |

Corsi Block Tapping, Digit Span Backwards, Spatial Working Memory, Object 2- back, Stop Signal Reaction Time, Stroop, Flanker |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Henning, A., Spinath, F.M., Aschersleben, G. (2010). | 2 | .17 | 175 | Maternal education, paternal education |

Dimensional Change Card Sort |

x | x | |||||||

| Ivrendi, A. (2011) | 3 | .47 | 70 | Maternal education, family income |

Head, Toes, Knees & Shoulders (HTKS) |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Kegel, C.A. & Bus, A.G. (2012). | 2 | .12 | 283 | Maternal education |

Stroop-like task (opposites), Stroop-like task (dogs), Digit span (words), WISC Backward Digit Span |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Knipe, H., (2009). | 3 | .06 | 125 | Parental education |

Backward Digit Span, Wisconsin Card sort, D-KEFS tower |

x | x | x | x | |||||

| Li-Grining, C. (2005) | 4 | .04 | 438 | Maternal education (less than HS vs. HS and above); Income-to-needs |

Shapes, Turtle/Rabbit |

x | x | x | x | |||||

|

Mezzacappa, E., Buckner, J.C., & Earls, F. (2011) & Mezzacappa, E. (2004). |

6 | .20 | 233 | SES | Flanker | x | x | |||||||

| Noble, K.G., McCandliss, B.D., & Farah, M.J. (2007). | 2 | .24 | 150 | SES composite | Spatial working memory task, Delayed nonmatch to sample, Go/no- go task, NEPSY auditory attention and response set |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Phillipson, S. (2009) | 1 | .21 | 215 | SES | Swanson Cognitive Processing Test |

x | x | |||||||

| Pinard, F. (2011). | 1 | −.04 | 102 | Hollingshead Four Factor Index of Social Status |

Day/night, Grass/snow, NEPSY-II Statue, NEPSY-II Auditory Attention |

x | x | |||||||

| Raver, C.C., McCoy, D.C., Lowenstein, A.L., & Pess, R. (2012). | 4 | .02 | 328 | Mother < HS education, Income-to-needs |

Balance Beam, Pencil Tap |

x | x | x | x | x | ||||

| Rhoades, B., Greenberg, M., & Domitrovich, C. (2009). | 3 | −.02 | 131 | Primary caregiver education |

Leiter-Revised Attention Sustained subtest, Day/Night, Peg Tapping |

x | x | x | ||||||

| Rhoades, B., Warren, H. K., Domitrovich, C. E., & Greenberg M. T. (2011). | 2 | .11 | 288 | Maternal education, Family income |

Leiter-Revised Attention Sustained Task |

x | x | x | ||||||

|

Sarsour, K., Sheridan, M., Jutte, D., Nuru-Jeter, A., Hinshaw, S., & Boyce, W.T., (2011). & Sarsour, K. S. (2007). |

6 | .37 | 60 | Income-to-needs ratio, Hollingshead Index of Occupational Status, Family wealth, Maternal education |

WISC Digit Span, Trail Making Test, Stroop Test |

x | x | x | x | |||||

| Wiebe, S.A., Espy, K.A., Charak, D. (2008). | 10 | .14 | 198 | Maternal education |

Delayed Attention, DAS Digit Span, Six Boxes, Delayed Response, NEPSY Statue, Whisper, Child Continuous Performance Task, shape school, NEPSY Visual Attention, Tower of Hanoi |

x | x | x | ||||||

Note. Correlations and sample sizes were averaged across all effect sizes reported in each study.

Edu = education; Inc = income; Occ = Occupation; SES = composite SES measure; WM = working memory; AS = attention shifting; In = inhibition; EF = composite EF; Other = other EF (e.g., planning, sustained attention)

Overall effect size

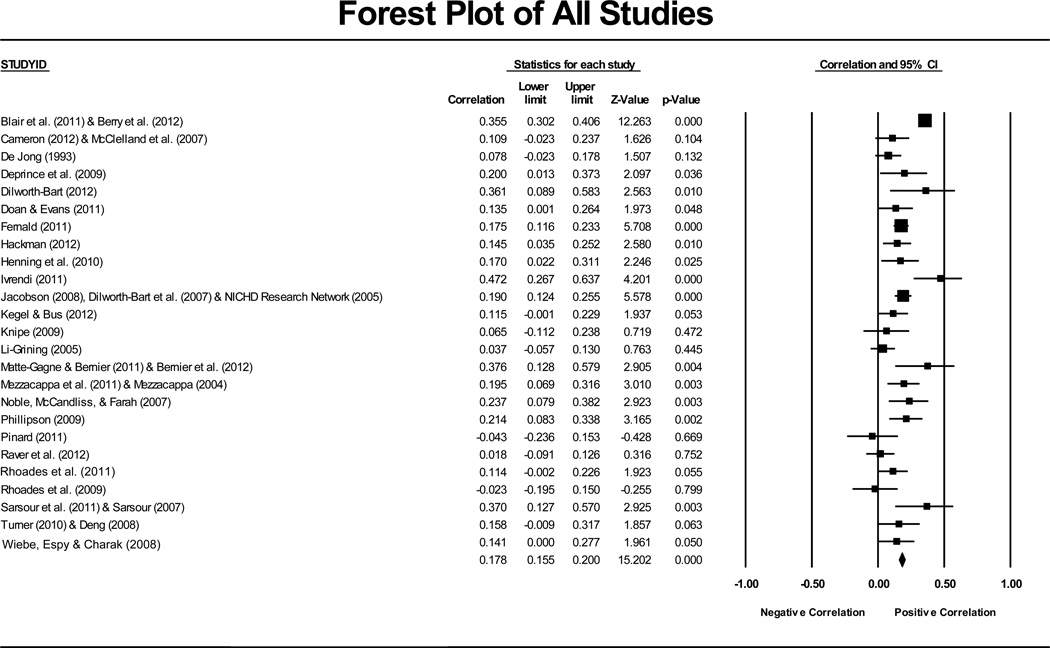

Taking all studies together, the strength of relation between children’s SES and EF was r = .16, 95% CI [.12, .21] using the random effects model, and r = .18, 95% CI [.16, .20] using the fixed effects model. These are conventionally considered “small” effect sizes. They were, however, significantly different from zero (z = 6.55, p < .001 for random effects model, z = 15.20, p < .001 for fixed effects model). The forest plot for these analyses is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of all studies included in the meta-analysis.

Tests for heterogeneity

The Q statistic indicated significant heterogeneity among the studies, Q (24) = 92.89, p < .001, as did the I2 index of 74.16 (Higgins et al., 2003). In order to test hypotheses about why some studies showed larger effect sizes than others, moderator analyses were performed.

Moderator analyses

Sample characteristics

Eight characteristics of the samples were assessed as moderators: intended sample SES, amount of SES variability, extent of exclusionary criteria for the sample, racial/ethnic composition of the sample, age range, mean age, and sex composition of the sample. Results of moderator analyses for categorical sample characteristics are displayed in Table 4. Of these, only amount of SES variability (Q (1) = 14.79, p < .001) emerged as a significant moderator using mixed effects models. Studies with meaningful SES variability (r = .22; k = 15) had significantly larger SES effect sizes than studies without meaningful SES variability (r = .08; k = 9). Using fixed effects models, racial composition (Qb (2) = 13.82, p = .001) and age range (Qb (2) = 15.20, p < .001) also emerged as significant moderators, and SES variability remained a significant moderator (Qb (1) = 35.58, p < .001). Studies using samples that were greater than 60% Black (r = .06; k = 2) had smaller effect sizes than studies with samples that were greater than 60% White (r = .16; k = 7) or were mixed race/ethnicity (r = .22; k = 10). Studies with a sample age range of < 2 years (r = .21; k = 13) had larger effect sizes than studies with sample ages ranges of 2–3.99 years (r = .12; k = 10). Meta-regression with random effects was used to assess mean age of the sample and sex composition of the sample as potential moderators. Neither mean age (slope = −.0008, p = .93) nor sex composition of the sample (slope = −.003, p = .58) were significantly associated with effect size, providing no evidence that either of these sample characteristics were associated with effect size.

Table 4.

Results of moderation tests for categorical sample characteristics using mixed effects models and fixed effect models.

| Mixed Effects Model | Fixed Effects Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | N | r | 95% CI | Q(df) | p | r | 95% CI | Qb(df) | p |

| Intended sample SES | 2.24(2) | .33 | .63(2) | .73 | |||||

| Low SES | 9 | .11 | .01− .21 | .18 | .15−.21 | ||||

| Representative/Diverse | |||||||||

| SES | 6 | .19 | .15− .24 | .19 | .15−.24 | ||||

| Convenience sample | 10 | .19 | .12− .26 | .16 | .12−.21 | ||||

| Amount of SES variability | 14.79 (1)** | < .001 | 35.58(1) | < .001 | |||||

| Meaningful variability reported | 15 | .22 | .16− .28 | .23 | .20−.25 | ||||

| Meaningful variability not reported | 9 | .08 | .04− .12 | .08 | .04−.12 | ||||

| Extent of exclusionary criteria | 1.01 (1) | .32 | .37(1) | .54 | |||||

| Minimal | 18 | .15 | .08−.22 | .18 | .15−.20 | ||||

| High | 5 | .20 | .13−.26 | .19 | .14−.24 | ||||

| Racial composition | 3.05 (2) | .22 | 13.82(2) | .001 | |||||

| >60% White | 7 | .16 | .09− .22 | .16 | .11−.20 | ||||

| >60% Black | 2 | .06 | −.03−.16 | .06 | −.02−.14 | ||||

| Mixed, none > 60% | 10 | .17 | .06− .27 | .22 | .18−.25 | ||||

| Age Range | 5.25 (2) | .07 | 15.92(2) | < .001 | |||||

| < 2 years | 13 | .19 | .12− .27 | .21 | .18−.24 | ||||

| 2 – 3.99 years | 10 | .12 | .07− .17 | .12 | .09−.16 | ||||

| 4 – 6.99 years | 2 | .26 | .11−.39 | .25 | .13−.36 | ||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Effect size characteristics

Four effect size characteristics related to the measurement of EF and SES were assessed as moderators: category of the SES construct, category of the EF construct, number of SES measures, and number of EF measures. As previously noted, several studies reported effect sizes for multiple levels of these effect size characteristics. Specifically, 9 studies reported effect sizes for two or more categories of SES construct, and 13 studies reported effect sizes for two or more categories of EF construct. Additionally, 2 studies reported correlations for two or more levels of the “number of SES measures” moderator, and 6 studies reported correlations for two or more levels of the “number of EF measures” moderator.

Meta-regression with random effects was used to assess “number of SES measures” and “number of EF measures” as moderators. For studies reporting effect sizes for more than one level of these variables, the effect size for the highest number of measures reported by the study was used in the meta-regression. As previously noted, the primary tests of moderation by category of SES construct and category of EF construct were conducted using a “shifting units of analysis” approach (Cooper, 2010), in which a given study was allowed to contribute one ES per level of the effect size characteristic being tested as a moderator.

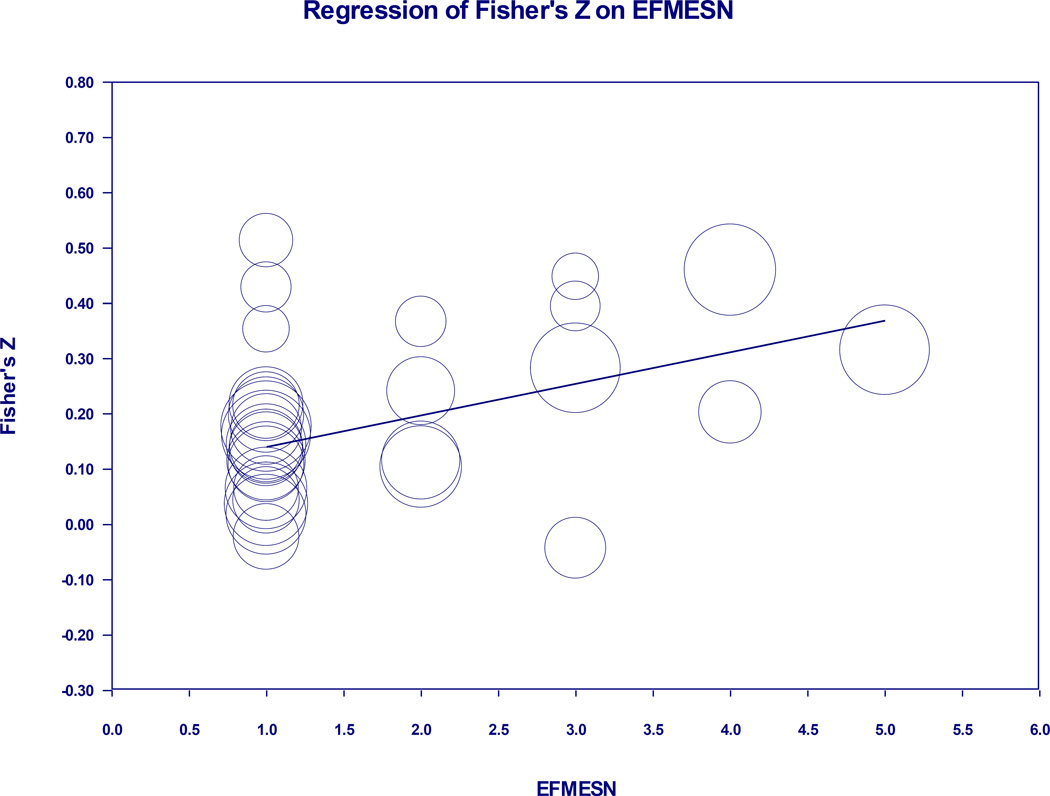

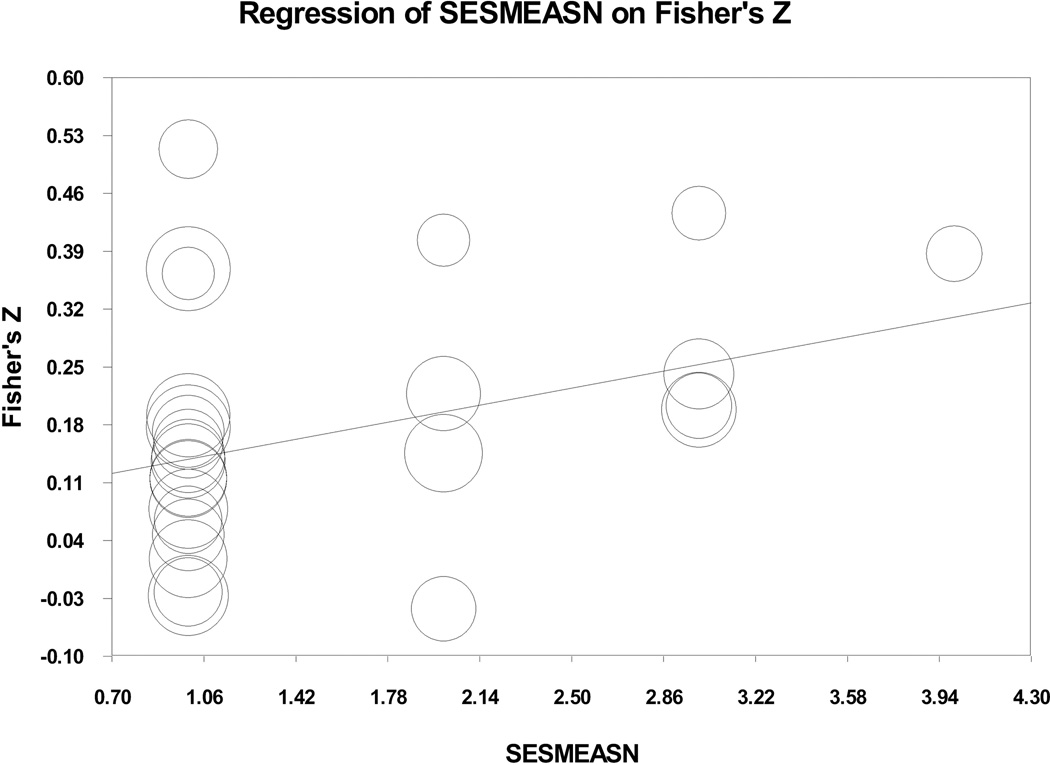

The meta-regression results revealed that the number of EF measures was significantly associated with effect size (slope = .06, p < .001). A scatterplot of the relationship between number of EF measures and effect size is shown in Figure 3. The relationship between the number of SES measures and effect size was marginally-significant (slope = .06, p = .08), and a scatterplot of the relationship between number of SES measures and effect size is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of the relationship between number of EF measures and effect size.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of the relationship between number of SES measures and effect size.

Results of moderator analyses for effect size characteristics using a “shifting units of analysis” approach are displayed in Table 5. Using mixed effects models, category of EF construct (Q (4) = 10.66, p = .03) significantly moderated effect sizes. The average correlation for effect sizes using composite EF measures was r = .28 (95% CI [.18–.37]), as compared to r = .18 (95% CI [.13–.22]) for working memory, r = .17 (95% CI [.08–.25]) for attention shifting, r = .14 (95% CI [.07–.22]) for inhibition, and r = .09 (95% CI [.06–.16]) for other measures of EF. Category of SES construct ((Q(2) = .79, p = .67) did not significantly moderate effect sizes.

Table 5.

Results of moderation tests for categorical effect size characteristics using mixed effects models and fixed effects models. In these models, each study contributed one effect size per version of the construct being tested as a moderator

| Mixed Effects Model | Fixed Effects Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | N | r | 95% CI | Q(df) | p | r | 95% CI | Qb(df) | p |

| Category of SES Construct | .79(2) | .67 | .48(2) | .79 | |||||

| SES Composite | 8 | .22 | .14−.30 | .22 | .15−.27 | ||||

| Income | 9 | .19 | .08−.29 | .20 | .17−.23 | ||||

| Education | 15 | .17 | .10−.25 | .21 | .19−.24 | ||||

| Category of EF Construct | 10.66(4)* | .03 | 71.81(4)** | < .001 | |||||

| Working memory | 12 | .18 | .14−.22 | .18 | .14−.21 | ||||

| Attention shifting | 7 | .17 | .08−.25 | .14 | .09−.20 | ||||

| Inhibition | 12 | .14 | .07−.22 | .11 | .06−.15 | ||||

| Composite using 2 or 3 of the above | 6 | .28 | .18−.37 | .31 | .28−.35 | ||||

| Other | 8 | .11 | .06−.16 | .13 | .10−.16 | ||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01

Publication characteristics

Two characteristics of the publications were assessed as moderators: type of publication and whether or not the publication focused on SES. Studies, rather than publications, were used as the unit of analysis in these analyses. Studies were excluded from analysis in cases where multiple publications from the same study received different codes on one of these characteristics (e.g., a published paper and an unpublished dissertation from the same study).

Results of moderator analyses for publication characteristics are displayed in Table 6. Using mixed effects models, type of publication (Q (1) = 5.05, p = .03) significantly moderated effect sizes, with larger effect sizes for published (r = .18; k = 18), as compared to unpublished (r = .08; k = 5), papers.

Table 6.

Results of moderation tests for publication characteristics using mixed effects models and fixed effect models.

| Mixed Effects Model | Fixed Effects Model | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | N | r | 95% CI | Q(df) | p | r | 95% CI | Qb(df) | p |

| Type of publication | 5.05(1) | .03 | 12.60(1)** | <.001 | |||||

| Published | 18 | .18 | .12−.24 | .19 | .17−.22 | ||||

| Unpublished | 5 | .08 | .01−.14 | .08 | .02−.14 | ||||

| SES as a primary focus | .75(1) | .39 | .26(1) | .61 | |||||

| Yes | 9 | .17 | .08−.25 | .14 | .10−.18 | ||||

| No | 12 | .13 | .09−.17 | .13 | .09−.17 | ||||

Note.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Publication bias

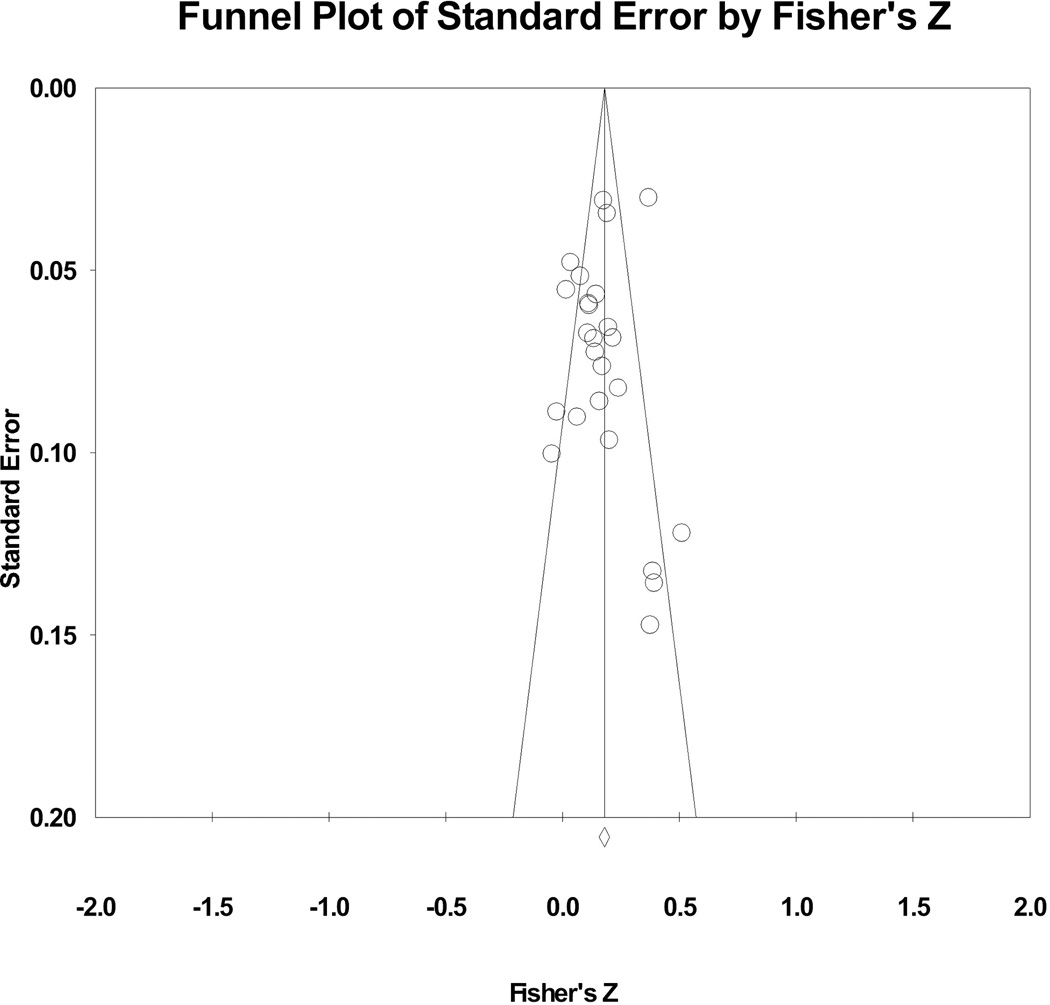

In order to determine the extent to which publication bias may have impacted the results of the current meta-analysis, publication bias was first assessed using all articles included in the meta-analysis. Standard errors for all datasets were plotted against effect size to generate a funnel plot. This plot is shown in Figure 5. In the absence of publication bias, studies should be distributed symmetrically around the average effect size. If publication bias is present, the bottom of the plot tends to show a higher concentration of studies to the right of the mean. Duval & Tweedie’s (2000) trim-and-fill procedure was used to correct for missing studies. Using the random effects model to look for missing studies to the left and right of the mean, 0 missing studies to the left of the mean were identified. The classic fail-safe N value indicates the number of non-significant studies that would be needed to nullify the effect (Rosenthal, 1979). The classic fail-safe N value was 1111, well above Rosenthal’s tolerance level of 135 for an unlikely number of nonsignificant studies (Rosenthal, 1979). Orwin’s fail-safe N indicates the number of studies with an effect size of zero that would be needed to bring the aggregated correlation to a ‘trivial’ size. Using r = .05 as the criterion for a trivial correlation, Orwin’s fail-safe N value was 65.

Figure 5.

Funnel Plot of Standard Error by Fisher’s Z for all studies included in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

The current paper provides the first meta-analytic synthesis of the literature on the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function performance among children. SES was significantly associated with EF, although the strength of the association varied markedly between studies. We were able to identify several factors that influenced the size of the SES-EF relationship.

Across the 25 studies included in the meta-analysis, an overall correlation or r = .16 between SES and EF was observed. However, a number of studies included in the meta-analysis were not designed to answer questions about SES and little SES variability in their samples, and corrections for range restriction and other artifacts were not made. Of the 15 studies with meaningful SES variability, the overall correlation was r = .22, suggestive of a small-to-medium relationship between SES and EF among socioeconomically diverse populations. The results of tests for publication bias did not suggest that these results were inflated by publication bias.

A primary objective of this meta-analysis was to investigate factors that moderate the strength of the relationship between SES and EF. This aim was particularly important given the large amount of heterogeneity between studies that was observed (Borenstein et al., 2009). The amount of SES variability in the sample emerged as a significant moderator, with meaningful SES variability associated with larger effect sizes. This conclusion must be qualified by the lack of objective and comparable criteria available across studies because studies varied greatly in the SES variability information they reported (e.g., means and standard deviations). Nevertheless, this moderator was coded with good inter-rater reliability, and it is likely that error in measuring this factor would decrease, rather than increase, its association with effect sizes. Further, this result is not surprising considering the fact that range restriction attenuates correlations (Hunter & Schmidt, 2004). These results therefore suggest that differing amounts of SES variability in samples may be a factor explaining discrepancies in observed relationships between SES and EF between studies. Thus, it is important for researchers to clearly report the amount of SES variability in samples (e.g., means and standard deviations of SES variables) and to consider range restriction when interpreting results.

Additionally, the way in which EF was measured influenced the magnitude SES-EF relationship. In particular, a higher number of measures used to calculate the EF variable related to a larger SES-EF effect size. Category of EF construct also emerged as a significant moderator, with composite EF measures showing the largest effect sizes (r = .28). One potential explanation for these results is reduced measurement error in EF variables derived from multiple measures (Spearman, 1910). This is particularly relevant in light of recent efforts to develop EF task measures with acceptable psychometric properties in response to the observation that most EF tasks commonly used with children have not undergone psychometric evaluation (e.g., Beck et al., 2011; Willoughby et al., 2010). Furthermore, when test-retest reliability of single EF measures in children has been reported, it has been found to be low by psychometric criteria (e.g., Bishop et al., 2001), which would attenuate correlations with other variables, such as SES.

To discover whether the relationship between SES and EF widens or narrows across time, we examined the mean age of the sample as a moderator. We found no significant relationship between this factor and the size of the SES-EF relationship. This is consistent with the small number of longitudinal studies that have examined the trajectory of the SES-EF relationship (Hackman et al., 2014; Hackman et al., 2015; Hughes, Ensor, Wilson, & Graham, 2010). Collectively, the present meta-analysis and the aforementioned studies suggest that the SES-EF relationship remains stable across childhood, rather than growing with the accumulation of SES-related experiences or narrowing as low-SES children “catch up” from a developmental delay.

While mixed-effect models did not find moderation by racial composition of the sample, fixed effects models did, with predominantly Black samples showing smaller effect sizes. However, these results should be interpreted cautiously, as only two samples were classified as greater than 60% Black, and both samples were also predominantly low SES, without meaningful SES variability reported. In addition to addressing this issue by moderator analysis, we also examined the individual meta-analyzed papers for information about the interaction between race/ethnicity and SES in predicting EF. One paper reported that this interaction was not significant (Sarsour, 2007) and the other reported that the income-EF association was greater for African-American children without having tested a statistical interaction (Dilworth-Bart, Khurshid, & Lowe Vandell, 2007). In sum, neither the results of the moderator analysis nor these individual studies provide clear support for the role of race in moderating the SES-EF relation.

Meta-analysis combines studies that may vary substantially in their measurement of variables and other methodological features, and this can be a strength or a weakness. It has been argued that, by averaging results from “apples and oranges,” meta-analysis may yield meaningless figures (Hunt, 1997). However, as Rosenthal and DiMatteo (2001) note, combining apples and oranges can yield especially useful information if one wants to generalize about fruit. Because the present meta-analysis combined a number of measures of SES (e.g., parental education, family income, composite measures), and a number of measures of EF (e.g., Digit Span tasks, Stroop tasks, Continuous Performance tests), it is subject to the apples and oranges criticism, but also enables is to report on the association between SES and the overall construct of EF, as well as with more specific categories (e.g., working memory, inhibition). Indeed, the moderator analyses allowed us to assess differences in the SES-EF relation depending on SES category, EF category, age, race and other potentially relevant variables.

Additionally, while the inclusion of a broad set of studies could be considered a strength of the present meta-analysis, it could also be considered a weakness in that many of the studies were not expressly designed to answer questions about the relationship between SES and EF (e.g., studies with extremely small variance in SES) and might therefore underestimate the size of the effect. Furthermore, the meta-analysis did not make corrections for restricted range or other study artifacts. The results, therefore, should not be interpreted as the relationship between SES and EF in the population as a whole, but rather as a summary of the correlations between SES and EF available in the current literature, including studies that were not designed to detect relationships between SES and EF.

It is also important to note that the current meta-analysis examined the raw association between SES and EF, without adjusting for related constructs, such as IQ. This reflects the state of the literature; none of the studies included in the meta-analysis report estimates of the SES-EF association after controlling for IQ. There is substantial construct overlap between EF and IQ, such that it may not be not meaningful to examine EF adjusted for IQ; this is likely to be among the reasons that researchers have not controlled for IQ in the studies reviewed here (Dennis et al., 2009). However, three of the papers reported information about the SES-EF association after controlling for a measure of verbal or language ability: one found that the SES-EF association persisted (Dilworth-Bart, 2012), another found that it did not (Turner, 2010), and a third found that some measures of language ability accounted for some measures of EF (Noble et al, 2007). Of course, the finding of mediators for the SES-EF relation does not necessarily diminish the reality or the importance of that relation.

The SES-EF relation is consistent with environmental influence on EF. Stress (e.g., Evans, 2004), parenting behavior (e.g., Evans, Boxhill & Pinkava, 2008), cognitive stimulation (e.g., Bradley, Corwyn, McAdoo & Coll, 2001) and language exposure (Hoff, 2003) all vary with SES, and could contribute to the differences summarized here. It is also true that executive functioning is highly heritable in studies using behavioral genetics methods (Engelhardt et al., 2015). EF ability likely involves interactions among numerous genetic and environmental factors (e.g., Deater-Deckard, 2014). The current meta-analysis assesses the strength of the SES-EF relation but is not able to reveal its causes.

Given the observed association between SES and EF, it is important for future research to investigate whether and how EF contributes to SES disparities in broader life outcomes. There is a plausible role for EF in shaping health behaviors, mental health, and academic achievement. The modest correlations observed between SES and EF makes it is unlikely that EF fully mediates SES disparities in academic achievement or health. However, small differences in childhood EF may have cumulative consequences across domains of development, a phenomenon that has been termed “developmental cascades” (e.g., Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Consistent with this, EF in childhood is predictive of a wide range of outcomes (e.g., Best, Miller & Naglieri, 2011; Williams & Thayer, 2009), suggesting that small differences in EF may shape development in meaningful ways. Thus, the role of EF, as well as other neurocognitive systems, as mediators of SES disparities in achievement and health is an important topic for further investigation.

Research Highlights.

Socioeconomic status has often been reported to predict childhood executive function. Here the strength of this relationship across studies was assessed using meta-analysis.

SES and EF were significantly associated across all studies, with substantial heterogeneity in effect size.

When all studies were considered together, small effects were found. Studies with more SES variability in the samples and more of EF measures resulted in larger effect size estimates, in the small-to-medium range

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant HD055689. The research reported here was supported [in whole or in part] by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant #R305B090015 to the University of Pennsylvania. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the paper.

References

Note: Studies included in the meta-analyses are marked with an *.

- Adler NE, Boyce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, Kahn RL, Syme SL. Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist. 1994;49(1):15–24. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.49.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]