Abstract

Important features of both stable and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are skeletal muscle weakness and wasting. Limb muscle dysfunction during an exacerbation has been linked to various adverse outcomes, including prolonged hospitalization, readmission, and mortality. The contributing factors leading to muscle dysfunction are similar to those seen in stable COPD: disuse, nutrition/energy balance, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, electrolyte derangements, inflammation, and drugs (i.e., glucocorticoids). These factors may be the trigger for a downstream cascade of local inflammatory changes, pathway process alterations, and structural degradation. Ultimately, the clinical effects can be wide ranging and include reduced limb muscle strength. Current therapies, such as pulmonary/physical rehabilitation, have limited impact because of low participation rates. Recently, novel drugs have been developed in similar disorders, and learnings from these studies can be used as a foundation to facilitate discovery in patients hospitalized with a COPD exacerbation. Nevertheless, investigators should approach this patient population with knowledge of the limitations of each intervention. In this Concise Clinical Review, we provide an overview of acute muscle dysfunction in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of COPD and a strategic approach to drug development in this setting.

Keywords: COPD, exacerbations, skeletal muscle, pharmacological interventions, drug development

Skeletal muscle weakness in association with reduced exercise capacity is frequently seen in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (1). Sarcopenia is often used to describe this state of abnormally low lean muscle mass combined with reduced muscle strength or function (2). Although this condition is considered to be a feature of aging, it has also been used in the specific context of COPD (3). Cachexia, on the other hand, is a more dynamic disorder in which active fat-free mass loss occurs in association with progressive pathologic processes, such as cancer and COPD (4). Whether due to sarcopenia or cachexia, skeletal muscle weakness is more prevalent and severe in patients with COPD than in age-matched seniors (1, 4) and is worsened by acute exacerbations of the disease (5). Although clinical consequences of muscle dysfunction in the setting of an acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) are incompletely understood, observations in recent studies have highlighted the importance of the relationship between muscle dysfunction and outcomes after hospitalization for AECOPD. For example, the likelihood of a first or subsequent hospital admission for a COPD exacerbation is correlated with reduced quadriceps bulk at time of discharge (6) and poor exercise performance (7, 8). Conversely, anabolic stimuli in the form of formal postdischarge pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) reduce both readmission and emergency room visits (9, 10). Despite these findings, the degree to which exacerbations may impact muscle function is variable and likely related to the underlying chronic dysfunction and the severity of illness occurring with the exacerbation, among other factors. Thus, the aim of this review is to focus on contributing factors to limb muscle weakness and current and emerging therapies for acute muscle dysfunction and to outline clinical trial concepts for drug development in this area.

Chronic Muscle Dysfunction in Stable COPD

Limb muscle dysfunction in COPD negatively affects quality of life, morbidity, and mortality (4). It is characterized by reduced muscle strength and/or endurance (4, 11), with the lower limbs generally being more affected than the upper limbs (12, 13). Reduced skeletal muscle mass, using fat-free mass index (FFMI) as a surrogate measure, is present in 4 to 39% of patients with COPD (14, 15). Although the prevalence generally increases with disease severity, reduced FFMI and quadriceps muscle mass have been reported across all Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease spirometric stages (1, 16) and body mass index (BMI) categories (17).

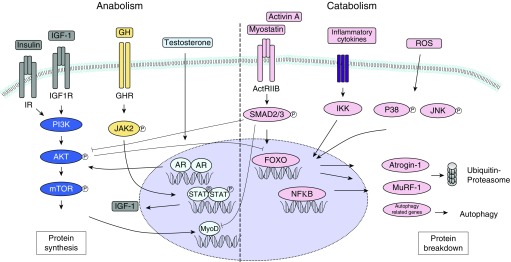

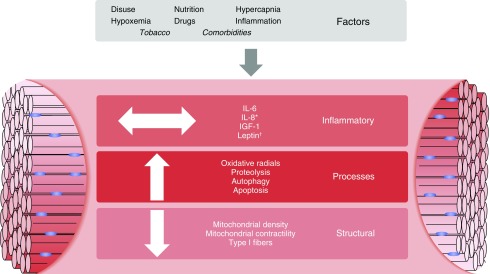

Several cellular signaling pathways that may contribute to the imbalance between muscle protein synthesis and protein breakdown have been implicated in limb muscle mass loss in patients with COPD (Figure 1). These pathways, together with other initiating factors, may lead to the changes observed in the peripheral muscles of this population (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of anabolic and catabolic signaling in skeletal muscle. A number of underlying mechanisms contributing to imbalance between muscle protein synthesis and protein breakdown have been implicated in limb muscle mass loss in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (4, 43, 104–107). The ubiquitin proteasome pathway is a major driver of muscle proteolysis and includes the forkhead box O (FOXO) transcription factor–regulated muscle-specific E3 ubiquitin ligases muscle ring finger protein 1 E3-ligase (MuRF-1) and atrogin-1 (105, 108). The autophagy–lysosomal pathway is another contributing mechanism to protein degradation in response to atrophic stimuli in the setting of COPD (107). Conversely, the GH–IGF-1–AKT–mTOR axis positively affects protein synthesis and may attenuate protein breakdown via AKT-mediated negative regulation of FOXO. ActRIIB = activin receptor type IIB; AKT = protein kinase B; AR = androgen receptor; GH = growth hormone; GHR = growth hormone receptor; IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factor 1; IGF1R = insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor; IKK = IκB kinase; IR = insulin receptor; JAK2 = janus kinase 2; JNK = Jun N-terminal kinase; mTOR = mammalian target of rapamycin; MyoD = myogenic differentiation 1; NFκB = nuclear factor-κB; P38 = p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase; PI3K = phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; ROS = reactive oxygen species; STAT = signal transducer and activator of transcription.

Figure 2.

Factors and consequences in acute and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)-related muscle dysfunction. The multiple factors related to muscle dysfunction in chronic and acute settings. Many of these factors are similar for both acute exacerbations of COPD and chronic stable COPD, with the notable exception of tobacco use and comorbidities (18, 21, 43, 54, 109). The large white arrows denote the direction of the impact. *Different muscle compartments show variable levels of cytokines. †Level dependent on time frame of illness. IGF-1 = insulin-like growth factor-1.

The morphological and biochemical changes in the peripheral muscle may in part be consequences of physical inactivity and can to some extent be reversed by training (18). Indeed, reduced quadriceps volume, capillarity, and strength are already present in mild COPD and are associated with reduced physical activity (16, 19). The chronic use of tobacco may be another contributor to skeletal muscle dysfunction, as smokers without obstructive lung disease have lower weight and lean body mass (LBM) than never smokers (20). Moreover, smokers or former smokers have weaker quadriceps than never smokers, and annual loss of fat-free mass is faster in patients with COPD who continue to smoke (1, 20, 21).

Acute Dysfunction in Exacerbations of COPD

Although the research on muscle dysfunction in the chronic setting may provide a guide for assessing acute muscle dysfunction, the evidence surrounding the latter is limited. Muscle dysfunction in AECOPD may also have parallels with ICU-acquired weakness (ICUAW), particularly in the area of protein homeostasis (22). It should be noted that there are important differences, as follows: first, patients with COPD always (whether diagnosed or not) have antecedent morbidity. Second, although certain associated characteristics, such as inflammation or immobility, are present in both conditions, ICU patients experience an extreme variety of these features. Although clearly more research is required to further elucidate the mechanisms that occur in the context of AECOPD, this article reviews some prominent factors that are believed to contribute to muscle dysfunction in this patient population (Figure 2).

Disuse Atrophy

Muscle disuse causes dysfunction through reduced protein synthesis and increased protein catabolism (23, 24), processes characteristic of inactivity. During hospitalization for AECOPD, which can last a median of 7 days (25), many patients spend less than 10 minutes per day walking (26). Of note, it has also been recently demonstrated that exacerbations treated as an outpatient are also associated with reduced physical activity (27). The specific effects of reduced activity in patients hospitalized for AECOPD can be further extrapolated from observations made in studies of normal healthy individuals submitted to bed rest (28). Within 1 week, reductions in body weight, leg lean mass, and strength were more pronounced in elderly compared with younger individuals (24). In some cases specifically assessing AECOPD, quadriceps muscle force is reduced, and quadriceps cross-sectional area (Qcsa) has been observed to decrease by up to 5% over 5 days of hospitalization (26, 29). Although Greening and colleagues found reduced Qcsa in hospitalized patients with AECOPD was linked to rehospitalization, longer hospital stays, and increased mortality (6), the same could not be said for the quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction (QMVC). They found that QMVC was not associated with rehospitalization or death after 1 year. Upper body strength, as measured by handgrip strength (HGS), has been found to be reduced in hospitalized patients with exacerbating COPD (29). The HGS test has also been associated with increased mortality for patients with COPD with values below the 10th centile (30). However, this parameter may be nonspecific, as it is often diminished in the elderly and those with chronic diseases (30, 31). Irrespective of their hospitalization status, patients with COPD who exacerbate have deterioration of the BMI, obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (BODE) index score, which does not return to baseline even after 1 year (32). There are numerous other physiological and functional consequences of an exacerbation; however, studies on the best tools to measure these changes in such a setting are lacking. We have summarized methods for the measurement of muscle dysfunction in COPD, with particular focus on those applicable to AECOPD (Table 1) (4, 33).

Table 1.

Assessments of Muscle Integrity and Function

| Endpoint | Subcategory Endpoint | Method | Test Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle mass | FFMI | DXA (33) | Noninvasive study for clinically stable patient |

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| Can be used to derive appendicular muscle mass | |||

| BIA (110) | Noninvasive study | ||

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| BIA is influenced by body water content | |||

| Measures composition of the whole body | |||

| Muscle CSA or volume | CT imaging (93) | Noninvasive study for clinically stable patient | |

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| MRI (111) | Noninvasive for clinically stable patient | ||

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| Ultrasound imaging (6) | Noninvasive study | ||

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| Can be performed at the bedside | |||

| Potentially more operator dependent than MRI or CT | |||

| Muscle phenotype | Oxidative phenotype | 31P-MRS (112) | Noninvasive study for clinically stable patient |

| Mainly assessable in research settings | |||

| Phosphocreatine recovery after exercise | |||

| Fiber-type proportion, mitochondrial density | Invasive study requiring muscle biopsy | ||

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| Intramuscular fat infiltration | MRI (113) | Noninvasive study for clinically stable patient | |

| Mainly assessable in research settings | |||

| Muscle strength | Isometric maximal volatile quadriceps muscle strength | Strain-gauge or computerized dynamometer | Active participation of patient required |

| Recommended in the recent ATS/ERS statement on limb muscle function in COPD as a methodology that can be implemented in clinical practice (4) | |||

| Nonvolatile measurement of quadriceps muscle strength | Magnetic or electrical stimulation of the femoral nerve (114) | Active participation of patient not required | |

| Feasible in research settings, but the techniques are not widespread | |||

| Reported to be safe, reproducible in elderly and severely sick (AECOPD, ICUAW) (114) | |||

| Hand grip strength | Handgrip dynamometer (30) | Active participation of patient required | |

| Muscle involvement in COPD preferentially involves lower limb; therefore, this approach may underestimate muscle weakness | |||

| Muscle endurance | Quadriceps endurance | Isometric quadriceps endurance using dynamometer (115) | Active participation of patient required |

| Repetitive magnetic stimulation (116) | Active participation of patient not required | ||

| Mainly assessable in research settings | |||

| Myoelectrical assessment of fatigue using EMG | Noninvasive if performed as surface EMG | ||

| Active participation of patient not required | |||

| Relationship between EMG signal and power output is not good, leading to concerns regarding the value of this test (117) | |||

| Functional capacity | 6-MWT | Submaximal exercise capacity test with patient-determined distance | Minimal equipment requirements |

| Active participation of patient required | |||

| MCID determined for patients with COPD (118) | |||

| Requires a hallway of at least 100 ft | |||

| Endurance shuttle walk test | A 10-m hallway course, variable speeds | Minimal equipment requirements | |

| Active participation of patient required | |||

| MCID determined for patients with COPD (119) | |||

| Incremental cycle ergometer test | Cycle ergometer | Active participation of patient required | |

| MCID determined for patients with COPD (118) | |||

| PFIT-s | The PFIT-s consists of sit-to-stand assistance, marching on the spot cadence, shoulder flexor and knee extensor strength | Active participation of the patient required | |

| Composite score assessing mobility and strength (120) | |||

| MCID determined for ICU patients | |||

| CPAx | Composite measure of respiratory function, cough, mobility, and strength | Active participation of patient required | |

| Functional scoring tool validated for general ICU patients (121) | |||

| Not specific for the muscle | |||

| TUG | Three main components: rising from a chair, walking, and sitting down (122) | Minimal equipment requirements | |

| Active participation of patients required | |||

| Assesses balance | |||

| 4MGS | Measured 4-m time course completed at usual speed | Minimal equipment requirements | |

| Active participation of patient required | |||

| Predicts readmission (123) and has established MCID (7), and also recognized as being of value by the EMA (see below) | |||

| SPPB | Assessment of balance, gait speed, and coordination | Minimal equipment requirements | |

| Active participation of patient required | |||

| Demonstrated relationship with function in COPD (124), 4MGS is a component, as is the sit-to-stand test, which has demonstrated validity in COPD and a functionally relevant cut-off in relation to quadriceps strength (125) | |||

| EMA considers SPPB may be the preferred instrument to assess physical frailty in many instances (96) |

Definition of abbreviations: 31P-MRS = 31P-magnetic resonance spectroscopy; 4MGS = 4-m gait speed; 6-MWT = 6-minute-walk test; AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ATS/ERS = American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society; BIA = bioelectrical impedance analysis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAx = Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment tool; CSA = cross-sectional area; CT = computed tomography; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; EMA = European Medicines Agency; EMG = electromyograph; FFMI = fat-free mass index; ICUAW = ICU-acquired weakness; MCID = minimal clinically important difference; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; PFIT-s = Physical Function in Intensive Care Test score; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TUG = timed up-and-go test.

Energy Imbalance

Weight loss has been observed in hospitalized patients with AECOPD (34) and may be due to reduced protein synthesis as seen in ICUAW (22). In addition, weight loss can worsen during hospitalization for those patients with COPD who are already underweight (35, 36). In stable COPD, a negative balance between energy intake and expenditure has been attributed to increased work of breathing (37, 38). This is further aggravated during a severe exacerbation when the resting energy expenditure (REE) increases partly in response to increased oxygen cost of ventilation, consequently leading to negative changes in body weight and muscle mass (38, 39).

The growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis positively affects protein synthesis in both the acute and chronic settings (36, 40). In the early phase of an exacerbation, IGF-1 may be elevated in response to hypoxemia or as a stress response and then be reduced in the recovery phase, under the influence of corticosteroids, a suppressor of the GH/IGF-1 axis (36, 40). In addition, leptin increases during the first days of an exacerbation, while patients are in a low intake/high REE state. Even though leptin should decline as REE decreases and food energy intake increases, in some patients it can remain elevated after 15 days (39, 40). The mechanism for this elevation is believed to be secondary to glucocorticoid use and systemic inflammation (40).

Local and Systemic Inflammation

In reality, leptin is one of many proteins that are altered in response to systemic inflammation during AECOPD (39). In fact, there are alterations of multiple systemic cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α), acute-phase reactants (C-reactive protein), and other proinflammatory markers, including fibrinogen (39, 41, 42). However, there is limited information regarding the character of the local inflammatory response at the muscle level (29, 43). Crul and colleagues found similar levels of IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression in the vastus lateralis muscle in those hospitalized for AECOPD, stable patients with COPD, and healthy adults (43). However, biopsies were performed on patients with AECOPD on hospital Day 4 and may have been influenced by glucocorticoids. On the other hand, Spruit and colleagues found that local IL-6 and IL-8 levels were inversely proportional to isometric quadriceps strength (29). In addition, increased circulating IL-8 levels were independently associated with the variance observed in handgrip and quadriceps strength in hospitalized patients with AECOPD (29). Given the inconsistent findings, additional studies are needed to evaluate the local effect of inflammatory processes on muscle function and repair during an exacerbation.

Hypoxia and Hypercapnic Acidosis

Hypoxia has an inhibitory effect on muscle protein synthesis by activating muscle proteolysis via stimulation of calcium-dependent proteases, whereas acidosis stimulates proteolysis mainly via the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (44). Because of inhibited hydroxylation, HIF-1α (hypoxia inducible factor-1α) is elevated in skeletal muscle during hypoxic states (45). The elevation of HIF-1α causes a downstream cascade of alterations in glucose and oxidative metabolism and DNA alteration affecting myosin heavy chain expression (45). The molecular mechanism for these local changes may be due to reduction of intracellular muscle pH, resulting in changes in myoelectrical signaling and reduction in muscle fiber conduction velocity (46, 47). Using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, it has been demonstrated that some patients with stable COPD develop a marked quadriceps acidosis during a sustained contraction (48), which is not seen in the upper limb, suggesting a mechanistic role for changes to muscle morphology. Even though the patients with COPD were sicker than the control subjects in this study, the results suggest potential interaction between hypercapnia, acidosis, and exercise-related fatigue (sustained contraction), which warrants further examination.

Electrolyte Dysfunction

Electrolyte imbalance, particularly hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia, are recognized causes of muscle dysfunction. Intuitively, one might think these disorders likely in patients who, in addition to aggressive treatment with β-agonist, often require diuretic therapy for comorbidities and whose disease may be worsened by the presence of hypercarbia (49). Few data exist in AECOPD, but it is clear that both hyponatremia and hypokalemia can occur (50, 51), although their impact on muscle force in this context is unknown. Older studies of patients with COPD with respiratory failure (in comparison with control subjects), found reduced intramuscular potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium but increased intramuscular chloride, sodium, and water (51, 52). However, correlation with muscle function tests was not performed, leaving an opportunity for newer studies to evaluate the role of electrolyte abnormalities in muscle dysfunction of AECOPD.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids, frequently used during AECOPD (53), indirectly reduce protein synthesis through down-regulation of IGF-1 (54, 55). In addition, glucocorticoids have been implicated in the elevation of leptin seen in the early days of an exacerbation (39) and activation of skeletal muscle mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic signaling pathways (56). Although glucocorticoids contribute to a negative nitrogen balance in both acute exacerbations and stable disease (57), corticosteroid use has not directly been linked to a reduction in muscle mass in stable patients (21) or a change in quadriceps strength (58). Furthermore, the correlation between glucocorticoid dose and quadriceps strength is not straightforward (29), thus raising the hypothesis that the effects may be an interaction between the steroids, immobility, and/or inflammation and not simply a steroid effect alone.

Therapies for Muscle Dysfunction in the AECOPD Population

The currently available therapies for muscle dysfunction in AECOPD include PR, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), and nutritional support (Table 2).

Table 2.

Current Therapies for Muscle Dysfunction

| Therapeutic Approach | Category | Examples of Interventions | Pros/Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutritional support | High-protein diet | >1.5 g of protein (4, 38) | May be appropriate after thorough nutritional evaluation; may be nitrogen load |

| Complete oral nutrition supplementation | Formulas vary; brands include ENSURE, BOOST | Potential link to reduced readmission, however, hospital formulations vary (34) | |

| Other nutritional supplements | Creatine (67, 68) | Mixed or negative data on effectiveness; insufficient evaluations in hospitalized AECOPD setting | |

| Coenzyme Q (68) | |||

| Vitamin D | |||

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | General | Varies: resistance, cardio; includes limb-specific exercises | Shown to increased exercise capacity and feelings of independence |

| Early initiation may not improve patient-reported outcomes (63) and may be linked to increased mortality (62) | |||

| Upper limb | Supported: arm weight is supported, including cycle ergometry, rear deltoid row, chest press, and biceps flexion with vertical shoulder press (59) | Improvement in both performance and endurance but not always dyspnea (59, 61) | |

| Unsupported: requires the activation of muscles that may be involved in respiration and/or in the support of the shoulder girdle during ADLs (e.g., lifting free weights) (59) | Potential risks of upper limb training are dynamic hyperinflation, a phenomenon usually seen at >50% of the maximum load obtained (126) | ||

| Lower limb | Exercises for lower limb include heel raises, knee extension with heel touching floor, hip flexion, knee extension with dorsal flexion of ankle (128) | Can improve quadriceps mass and strength, which are linked to mortality outcomes (61, 127) | |

| Neuromuscular electrical stimulation | NMES | NMES only | Generally, has been shown to be safe but higher mortality in intervention group in Greening and colleagues study (62) |

| NMES and PR | NMES PR |

Definition of abbreviations: ADLs = activities of daily living; AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NMES = neuromuscular electrical stimulation; PR = pulmonary rehabilitation.

Pulmonary Rehabilitation and Specific Muscle Training

Exercise training for patients with AECOPD can be generalized or limb-specific (upper or lower) with the goal of improving performance, endurance, and strength (4, 59–61). Ultimately, the objective of this aspect of PR in AECOPD may be twofold: to prevent loss and/or induce recovery. A Cochrane review of nine studies in patients with AECOPD found benefits in readmission and mortality in those undergoing inpatient and/or outpatient PR soon after an exacerbation when compared with usual care (60). However, two recent studies in patients with AECOPD and ICU patients suggest the benefits may be limited (62, 63). Greening and colleagues initiated PR during hospitalization and showed fewer benefits and potential concerns for early (inpatient) PR initiation when used in conjunction with NMES (62). Furthermore, they found no difference in QMVC of those who were not readmitted, regardless of study group assignment (62). Notably, there was limited exercise training during hospitalization (average of fewer than three sessions each of aerobic and resistance training) and limited use of PR after hospital discharge in the intervention group. In addition, a randomized trial of standard rehabilitation versus usual care in 300 patients admitted to the ICU because of respiratory failure did not yield any advantage in patient-related outcomes (63). Although the reason for these results is unclear, it may be prudent to initiate PR once the patient’s full capacity to participate in rehabilitation returns to a level tolerable of increasing workloads. Despite these controversies, informed opinion suggests that PR is severely underused for multiple reasons, including patient perception of benefit and feasibility of travel (61). Regardless of the goals or methods of PR in the acute condition, the stability and individual needs of the patient should be considered before initiation.

NMES

NMES is the application of electrical current over target muscles stimulating motor neurons and causing a muscular contraction (4). Zanotti and colleagues showed that muscle strength improved with active limb exercises and electrical stimulation in mechanically ventilated patients with COPD (64). The largest study in this area is that of Greening and coworkers, who assessed 386 subjects, of whom 82% (n = 320) were patients admitted with a COPD exacerbation, to either inpatient rehabilitation using a regime incorporating NMES vide infra or best supportive care (62). As discussed above, this study failed to demonstrate a benefit for inpatient rehabilitation and revealed higher mortality in the intervention group, which might have been due to reduced uptake of rehabilitation after hospitalization (62). Therefore, one concern for NMES may be the timing of application, given the anabolic/catabolic balance shifts throughout AECOPD (65). Recently, NMES has shown to be useful in outpatients with stable COPD (66) and may yet have a role during early convalescence from AECOPD. More studies are needed to define the population that could benefit from this therapy.

Nutritional Support and Supplements

Reduced intake of nutrients such as proteins and fats in the first few days of hospitalization has led to suggestion for a high-protein diet (38). In fact, a dietary protein intake of greater than 1.5 g/kg/d has been suggested as a means to prevent weight loss after an exacerbation, on the basis of studies in this population (4, 38). More generally, a recent retrospective study showed that patients with a primary diagnosis of COPD who received complete oral nutritional support while hospitalized experienced a reduction in length of stay by 1.9 days and a 13.1% lower chance of 30-day readmission (34). Because this study was performed using Medicare claims data, the nutrition programs of the hospitals analyzed may vary, limiting the recommendations that can be distilled from the study results. Indeed, Puthucheary and colleagues found that administration of protein for ICUAW was associated with increased muscle wasting (22). However, this study may be of limited applicability to the AECOPD setting, as only a small number of patients with COPD were included (9 out of 63, 14.3%), one-third of all subjects had no antecedent chronic illness, and many experienced multiorgan failure during their ICU course. In addition to oral nutritional support and bulk protein administration, nutrients such as creatine and coenzyme Q10 have been evaluated as potential therapies to treat muscle dysfunction in COPD but have been met with poor or limited results (67, 68). Finally, although vitamin D appears to be important for skeletal muscle health, as demonstrated by studies in both murine and human models (69, 70), its importance in acute muscle dysfunction in COPD has not been fully evaluated. Because of the mixed data, surrounding nutritional and protein administration for acute muscle dysfunction, nutritional risk screening and phenotyping with biological markers have been suggested before instituting a specific regimen (37).

Emerging Therapies

The major classes of emerging therapeutics for muscle dysfunction are androgens, myostatin inhibitors, GH analogs, and ghrelin receptor agonists (Table 3). Several of these drugs directly increase muscle mass and/or function. However, studies of these therapies have been focused mainly in chronic or subacute debilitating diseases, such as cancer and heart failure, and most lacked the inclusion of structured exercise and nutritional plans.

Table 3.

Emerging Therapies for Muscle Dysfunction

| Class | Drug | Populations* | Tools | Notable Outcomes | Adjunct Therapy | Adverse Events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Androgens and progesterone | Megestrol (multiple) | COPD, cancer cachexia, HIV/AIDS–related cachexia | DXA | ↑ Weight after 2 wk, confirmed as fat on DXA (77) | No planned nutrition or PR | Similar to placebo; mostly dyspnea |

| Multiple studies complete/ongoing | Spiro | |||||

| 6-MWT | ||||||

| Mahler-Q | ||||||

| CRD-Q | ||||||

| Oxandrolone (multiple) | COPD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, HIV, cancer cachexia, FTT, chronic infection, surgery | BIA | ↑ Weight, ↑ in LBM at up to 4 mo, nonsignificant ↑ in 6-MWD (73) | No planned nutrition or PR | Edema, ↑ LFTs studies | |

| Multiple studies complete/ongoing | Spiro | |||||

| 6-MWT | ||||||

| Karnofsky | ||||||

| VAS | ||||||

| Enobosarm (SARM) | Cancer cachexia | DXA | ↑ Total LBM, ↓reduction in stair climb time (76) | No planned nutrition or PR | Nausea, anemia, GI disturbances | |

| Multiple studies complete/ongoing | FAACT | |||||

| FACIT-F | ||||||

| SCP | ||||||

| HGS | ||||||

| SCT | ||||||

| Myostatin pathway inhibitors | Landogrozumab (LY2495655) (Lilly) | Pancreatic cancer cachexia, hip arthroplasty, muscle atrophy | DXA | Trend toward change in aLBM at 12 wk; probability of difference between treatment vs. PBO did not meet statistical significance (128) | Vitamin D supplementation for deficiency; no planned nutrition or PR | Injection site irritation; 7 patients developed anti-LY2495655 antibodies (no clinical significance) |

| Multiple completed studies in various populations | TUG | |||||

| SCP | ||||||

| Leg extension | ||||||

| PINTA/AMG 745 (Atara Biotherapeutics/AMGEN) | Prostate cancer cachexia | DXA | ↑ LBM at 29 d, ↔ SPPB, ↔ leg extension (81) | No planned nutrition or PR | Syncope (1 patient), fatigue, diarrhea, injection site bruising; 1 patient developed anti-AMG 745 antibodies (no clinical significance) | |

| Discontinued by manufacturer | CT | |||||

| Leg extension | ||||||

| SPPB | ||||||

| Bimagrumab (BYM338) (Novartis) | COPD, IBM, IIM, sarcopenia, mechanical ventilation | DXA | ↑ TMV vs. placebo at 4, 8, and 24 wk, ↔ 6-MWD at 24 wk (80) | No planned nutrition or PR | Transient, mild, involuntary muscle contractions | |

| Multiple studies ongoing | 6-MWT | |||||

| TMV | ||||||

| Ghrelin receptor agonist | SUN11031 (Daiichi Sankyo) | COPD | DXA | ↓ 6-MWD in low dose vs PBO, ↔ HGS, ↔ SPPB, post hoc analysis of cachexic subjects show statistically significant ↑6-MWD, HGS, SPPB (89) | No planned nutrition or PR | COPD-related symptoms, injection site irritation, headache, weight reduction; MI in 7 subjects (unrelated to drug) |

| Discontinued by manufacturer | 6-MWT | |||||

| Spiro | ||||||

| SPPB | ||||||

| HGS | ||||||

| Anamorelin (Helsinn Therapeutics) | Cancer cachexia | DXA | ↑ TBM, LBM, and aLBM after 12 wk, ↔ HGS, ↔ FACT (91) | No planned nutrition or PR | Uncontrolled diabetes, hyperglycemia, GI disturbances, edema | |

| Studies completed | HGS | |||||

| FACT | ||||||

| Capromorelin (Pfizer) | Sarcopenia (older adults, age 65–84 yr) | 6-MWT | ↑ SCT after 12 mo, ↔ 6-MWD, nonsignificant ↑LBM after 6 mo (88) | Discontinued by manufacturer | Hyperglycemia (↑ HA1c), insulin resistance, glucosuria, ↑ cholesterol | |

| Discontinued by manufacturer | HGS | |||||

| TWS | ||||||

| SCT | ||||||

| DXA | ||||||

| MMSE | ||||||

| SF-36 | ||||||

| PAI | ||||||

| MOS-SS | ||||||

| β-Receptor blocker | Espindolol (MT-102) (PsiOxus) (nonselective β-blocker) | Colorectal and NSCLC cachexia | DXA | ↑ Weight 4 wk (high dose vs. PBO), ↑ HGS, ↑ 6-MWD, SCP, nonsignificant trend toward improved SPPB (high dose vs. PBO) (129) | Multiple studies complete/ongoing | Anemia, cough, dyspnea |

| HGS | ||||||

| Multiple studies complete/ongoing | 6-MWT | |||||

| SCP | ||||||

| SPPB | ||||||

| EQ-5D |

Definition of abbreviations: 6-MWD = 6-minute-walk distance; 6-MWT = 6-minute-walk test; aLBM = appendicular lean body mass; BIA = bioelectric impedance analysis; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRD = chronic respiratory disease; CT = computed tomography; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; EQ-5D = EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire; FAACT = Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy score; FACIT-F = Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; FACT = Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; FTT = failure to thrive; GI = gastrointestinal; HA1c = hemoglobin A1c; HGS = handgrip strength; IBM = inclusion body myositis; IIM = idiopathic inflammatory myopathy; LBM = lean body mass; LFT = liver function test; MI = myocardial infarction; MMSE = Mini Mental Status Examination; MOS-SS = Medical Outcomes Study-Sleep Scale; NSCLC = non–small-cell lung cancer; PAI = Physical Activity Index; PBO = placebo; PR = pulmonary rehabilitation; Q = questionnaire; SARM = selective androgen receptor modulator; SCP = stair-climbing power; SCT = stair-climbing time; SF-36 = 36-item short form health survey; SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery; TBM = total body mass; TMV = thigh muscle volume; TUG = timed up-and-go test; TWS = tandem walk speed; VAS = visual analog scale.

Populations in bold were studied in the trial referred to under the “Notable Outcomes” section.

Androgens and Progesterone

Anabolic steroids affect muscle tissue by inducing protein anabolism via androgen receptors while inhibiting catabolism through neutralization of the glucocorticoid receptor (71). Unlike bulk protein administration during acute illness, androgens do not generate large quantities of urea and heat (71). Nandrolone and oxandrolone have been the best-studied androgens in COPD (72, 73). Oxandrolone was approved for patients with weight loss due to chronic infection, extensive surgery, or idiopathic failure to thrive (73). Oxandrolone increased LBM in an open-label, prospective, multicenter trial of a stable outpatient COPD population with cachexia. However, the applicability of the results of the study is limited because of the lack of a control group and high dropout rate (73). Testosterone has been reported to be low in some patients with COPD, although an association with reduced muscle function has not consistently been shown (72, 73). However, in a four-way study with resistance training in COPD (74), participants who were randomized to receive both training and testosterone gained the most muscle mass. Concerns regarding the side effects of testosterone have limited its use, but this may be mitigated by using selective androgen receptor modulators. Selective androgen receptor modulators, studied in cancer cachexia, have shown potential to increase weight, strength, and function (75, 76), while minimizing the side effects often seen with testosterone treatment. Finally, megestrol acetate may benefit muscle dysfunction because of its effect on appetite and weight gain, in addition to stimulating ventilation. In one study, the drug increased weight in patients with COPD but, like several other androgens, failed to significantly improve 6-minute-walk distance (6-MWD) (77).

Myostatin Inhibitors

Myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor-β protein superfamily, is a negative regulator of muscle growth and is elevated in states of cachexia, including COPD (78). There are several drugs in this category, including bimagrumab (BYM338), landogrozumab (LY2495655), AMG/PINTA 745, and trevogrumab (REGN-1033) (Table 3). Bimagrumab (BYM338), which blocks ActRIIB (activin receptor type IIB), has been studied in various disease states, including stable COPD, sarcopenia, and inclusion body myositis (79, 80). In the COPD study, bimagrumab showed statistically significant increase of up to 7% in thigh muscle volume by magnetic resonance imaging at 4, 8, and 24 weeks when compared with placebo (80). There was no improvement in functional outcomes, including the 6-MWD. In a 4-week study of patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen deprivation therapy, AMG 745 caused a 1.5% increase in LBM and 1.7% reduction in body fat when compared with placebo at Day 29 but failed to show any improvement in functional parameters (81).

GH

Once secreted by the anterior pituitary, GH acts via mediators, including IGF-1, to initiate a multitude of biological processes. GH regulation of IGF-1 and its interplay with myostatin have been demonstrated in patients with COPD (42). Despite its potential uses, there is concern for safety, given an important study that demonstrated increased mortality in ICU patients receiving GH (82). The causes of the excess mortality in that study have been debated, but there was a reduction in GH-associated interventional clinical trials in the subsequent years (83). Clinical trials of GH in respiratory patients have yielded mixed results (84, 85). Pape and colleagues performed an uncontrolled study, finding weight gain and increased maximal inspiratory pressures in patients with COPD treated with recombinant GH (85). In another study, a randomized controlled trial, patients with COPD showed no improvement in strength and endurance compared with placebo and worse 6-MWD (84).

Ghrelin

Because of controversy surrounding the safety of GH, increasing enthusiasm exists for the use of GH secretagogues, such as ghrelin and ghrelin receptor agonists. Ghrelin stimulates secretion of GH, via growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1a (GHS-R1a), leading to regulation of multiple functions, from food intake to glucose metabolism (86). In humans, ghrelin has been studied in cancer cachexia, sarcopenia of the elderly, chronic heart failure, and COPD (87–91). In patients with COPD, ghrelin improved LBM and muscle strength but had mixed results on functional outcomes such as the 6-MWD (87, 90). SUN11031, another synthetic human ghrelin, was studied by Levinson and Gertner in clinically stable cachexic patients with COPD (89). This study enrolled 192 patients with BMI less than 21 kg/m2 and FFMI less than 16 kg/m2. Results showed that up to 65% of subjects in both treatment groups gained at least 3% of their body weight after 85 days of treatment (89). Another drug, capromorelin, was tested for 1 year in adults older than 65 years of age with evidence of functional decline on the basis of the Short Form-36 Health Survey and HGS (88). After 12-month treatment, there was a 7% increase in stair climb (vs. 0.9% placebo, P = 0.02) and a decrease in tandem walk time.

Finally, anamorelin has shown promise in cancer cachexia. Results of ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 (Anamorelin in Patients with Non-small-cell Lung Cancer and Cachexia) studies showed an increase in LBM but no improvements in functional outcomes such as handgrip strength (91).

Considerations for Drug Development to Treat Acute Muscle Dysfunction

Given the learnings from therapeutic studies performed in stable/chronic settings and in subjects without COPD, we have developed recommendations for drug development targeting muscle dysfunction in hospitalized patients with AECOPD. These recommendations are summarized in Table 4, and further considerations may be found in a recent review by Steiner and colleagues (92).

Table 4.

Recommendations for Clinical Trial Considerations for Muscle Dysfunction in COPD

| Hospitalized, Non–Mechanically Ventilated AECOPD | Mechanically Ventilated AECOPD | Stable COPD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions | Androgens, GH analogs, ghrelin agonists, myostatin inhibitors, NMES |

||

| Endpoint | 90-d readmission (30- or 60-d may be considered) | Ventilator-free days | QoL |

| Length of hospitalization | Physical function | ||

| Physical function | Physical function | Muscle strength | |

| Muscle strength | Muscle strength | ||

| QoL | QoL | ||

| Inclusion/stratification | Muscle strength (QMVC) | Muscle strength | Muscle strength |

| Muscle mass (CSA, FFMI) | Muscle phenotype | Muscle mass | |

| Muscle phenotype (BX*) | Muscle fiber composition | Muscle phenotype | |

| Physical capacity (TUG, 4MGS, 6-MWT) | Physical capacity (CPAx) | Physical performance | |

| Duration | 3 wk to ≥3 mo | 3 wk to 3 mo | 8 wk to ≥6 mo |

| Exercise | Yes | Maybe (ICU dependent) | Yes |

| Timing | Discharge/postdischarge

|

Postdischarge | Outpatient |

| Assessments | Muscle strength | Muscle strength | Muscle strength |

| Muscle mass | Physical function | Muscle mass | |

| Muscle fiber composition | QoL | Muscle fiber composition | |

| Physical function | |||

| QoL | |||

| Nutrition | Controlled | Controlled | Controlled |

| Real world | |||

| |

|||

| Other | Age, sex, race/ethnicity, location, additional medications (e.g., oral glucocorticoid, supplements) | ||

Definition of abbreviations: 4MGS = 4-m gait speed; 6-MWT = 6-minute-walk test; AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BX = biopsy; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPAx = Chelsea Critical Care Physical Assessment tool; CSA = cross-sectional area; FFMI = fat-free mass index; GH = growth hormone; NMES = neuromuscular electrical stimulation; QMVC = quadriceps maximal voluntary contraction; QoL = quality of life; TUG = timed up and go test.

Fiber-specific interventions.

Inclusion/Stratification

The studies of emerging therapies in the stable COPD setting have shown inconsistent improvement across parameters of muscle dysfunction (Table 3). In an acute setting, it is possible that these drugs may provide greater benefit because of the degree and nature of muscle dysfunction. Therefore, careful consideration needs to be given to the inclusion criteria for a study with a novel intervention. Given current knowledge, it seems sensible to stratify entrance into the study by physical performance, muscle strength, and/or skeletal muscle composition. On the basis of recent studies, Qcsa may be a useful inclusion criterion because of its predictive ability and bedside accessibility (6, 93). Although QMVC was found to be variably impacted in AECOPD and therefore limited as an outcome (62), it may prove to be a good stratification tool to direct therapy toward the most affected individuals. Depending on the severity of the exacerbations, assessment of physical capacity using a tool such as the Short Physical Performance Battery can inform on weakness in the lower limb (94), and the 4-m gait speed component is predictive of readmission in the context of AECOPD.

Outcome Measures

In conjunction with determining the appropriate inclusion criteria for the study, endpoint measurement(s) must be established. Regulatory endpoints fall into two major categories: objective physiological assessments (pulmonary function tests and exercise capacity) and patient-reported outcome measurements (symptom scores, activity scales, and health-related quality-of-life instruments) (Table 5) (95). The Short Physical Performance Battery, which is widely used in gerontology and relates to quadriceps structure and function in COPD (94), has recently been suggested by the European Medicines Agency for use in clinical trials (96). In addition, submaximal constant work rate endurance time is being prepared for submission for qualification (97).

Table 5.

Selected Patient-reported Outcomes

| Outcome Measure | Components | Recall Period | Year Published | MCID | Approved (Agency) | AECOPD Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom/activity scales | ||||||

| EXACT-PRO (130) | Questions: 14 | 1 d | 2010 | Undefined | Yes (FDA, EMA) | Yes |

| Domains: breathlessness, cough and sputum, chest symptoms | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (asymptomatic) to 100 (severely symptomatic) | ||||||

| E-RS (131) | Questions: 11 | 1 d | 2014 | 1–3 units, varies by domain | Yes (FDA, EMA) | Yes |

| Domains: breathlessness, cough and sputum, chest symptoms | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (asymptomatic) to 40 (severely symptomatic) | ||||||

| MMRC* (131) | Questions: 1 | Undefined | 1952 | Undefined | Yes (FDA, EMA) | No |

| Domains: undefined | ||||||

| Scale: grade 1 (breathless with strenuous exercise) to 5 (breathless with minimal activity) | ||||||

| Health-related QoL | ||||||

| SGRQ-C (95) | Questions: 50 | 4 wk, 3 mo, 1 yr | 1992 | 4 units | Yes (FDA) | No |

| Domains: symptoms, activity, impact of disease on daily life | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (no impairment) to 100 (completely impaired) | ||||||

| CRQ (132) | Questions: 20 | 2 wk | 1987 | 0.5 per domain | No | No |

| Domains: dyspnea, emotional function, fatigue, and mastery | ||||||

| Scale: 1 (severe impairment) to 7 (no impairment) per domain | ||||||

| SF-36 (133) | Questions: 36 | 1 wk, 4 wk | 1992 | Undefined | Yes (FDA) | Yes |

| Domains: physical and mental subscales: physical function, mental health, energy, health perception, physical role limitation, mental role limitation, social function, and pain | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (negative health) to 100 (positive health) | ||||||

| CAT (131) | Questions: 8 | Undefined | 2009 | 1–3 | Yes (FDA) | Yes |

| Domains: undefined | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (no impact) to 40 (severe impact) | ||||||

| Multidimensional | ||||||

| Modified BODE (134, 135) | Questions: 4 areas | N/A | 2004 | Undefined | Yes (FDA, EMA) | No |

| Domains: FEV1 (% predicted), 6-MWT, dyspnea scale score, BMI | ||||||

| Scale: 0 (best) to 10 (worst) | ||||||

| PROactive (98) | Questions: D-PPAC: 30, C-PPAC: 35 | 7 d | 2014 | Undefined | No | Yes |

| Domains: amount of activity, difficulty of activity (performed daily or in clinic) | ||||||

| Scale: Yet to be established |

Definition of abbreviations: 6-MWT = 6-minute-walk test; AECOPD = acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI = body mass index; BODE = body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise; CAT = COPD Assessment Test; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; C-PPAC = Clinical Visit PROactive Physical Activity in COPD; CRQ = Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire; D-PPAC = Daily PROactive Physical Activity in COPD; EMA = European Medicines Agency; E-RS = Evaluating Respiratory Symptoms; EXACT-PRO = The Exacerbations of Chronic Pulmonary Disease Tool–Patient-reported Outcome; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration; MCID = minimal clinically important difference; MMRC = Modified Medical Research Council; N/A = not applicable; QoL = quality of life; SF-36 = 36-item Short-Form Health Survey; SGRQ = St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; SGRQ-C = COPD-specific SGRQ.

There are several characteristics that the FDA takes into account when reviewing a new or modified patient-reported outcome: concepts being measured, number of items, conceptual framework of the instrument, medical condition for intended use, population for intended use, data collection method, administration mode, response options, recall period, scoring, weighting of items or domains, format, respondent burden, and translation or cultural adaptive availability (136).

FDA classified as activity scale but also considered in symptom scale.

Another endpoint that may in due course be validated as an outcome is the European Union Innovative Medicine Initiative Patient reported outcome (PROactive) tool (98), which aims to capture the patient experience of physical activity. The consortium conducted a 6-week, multicenter, randomized, two-way crossover study in 236 patients with stable and exacerbated COPD. The scores on the questionnaire correlated with patient quality of life, dyspnea, and exercise capacity (98). Finally, endpoints such as hospital 30- or 90-day readmission can be used as an objective nonphysiological assessment, while having the value of being attractive to payers (e.g., insurance companies) and prognostic indicators of mortality (99, 100).

Timing

The timing of the intervention and duration of administration are important parameters that, although dependent the drug’s mode of action, require careful coordination with patient discharge planning. In patients hospitalized with AECOPD, initiating treatment at the time of discharge or shortly after discharge has several advantages. The first advantage is knowing that the patient is to survive hospitalization, given the inpatient morality rate of 2 to 5% (99, 101). In addition, initiating treatment after discharge allows for confirmation of AECOPD diagnosis and fewer confounding factors, such as use of systemic glucocorticoids.

Duration

Duration of treatment can vary depending on the characteristics of the drug. For example, bimagrumab increased thigh muscle volume at 8 weeks of treatment (80), although there was no evidence of functional improvement. With due consideration for a medicine’s mode of action, a longer treatment period, with a minimum of 3 months, may provide enough time for assessment of physiological, functional, and nonphysiological endpoints. Stable outpatient COPD and mechanically ventilated patients with exacerbated COPD may require longer or shorter lengths of treatment, depending on the goal of the trial.

Adjunct Therapy

Many of the drug studies we reviewed did not include PR or nutritional interventions. For prevention and intervention studies in sarcopenia, the preference is for incorporation of exercise and nutrition because of perceived benefits (102, 103). However, in the recovery phase from AECOPD, PR and nutritional interventions might obscure benefits from a potentially effective medicine. Thus, in early-phase trials designed to provide a “reason to believe,” it may be desirable to include an arm that does not contain formal PR or allow PR on the basis of physician discretion, with understanding of the variability it may introduce into the study.

Conclusions

It is now accepted that muscle weakness and consequent limitation to activities of daily living and exercise is a feature of COPD. During a hospitalization for an exacerbation, muscle strength, physical activity, and exercise performance are further impaired and are markers of increased future risk. Therefore, the period around an exacerbation represents a crucial moment to explore interventions that may reverse these processes. In the chronic setting, there have been mixed results in therapeutics for muscle dysfunction. An improved understanding of the contributing factors to acute muscle dysfunction and important clinical trial concepts for drug development in this area may prove a promising therapeutic avenue to reduce morbidity associated with hospitalization for AECOPD. The recent efforts to improve evaluation of outcomes in this population, including the PROactive consortium, will ensure future availability and adoption of drug development tools that are accepted by regulatory agencies to expedite the development of novel therapies focused on muscle dysfunction in the acutely ill patient with COPD.

Footnotes

CME will be available for this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0615CI on October 24, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Seymour JM, Spruit MA, Hopkinson NS, Natanek SA, Man WD, Jackson A, et al. The prevalence of quadriceps weakness in COPD and the relationship with disease severity. Eur Respir J. 2010;36:81–88. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00104909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singer JP, Lederer DJ, Baldwin MR. Frailty in pulmonary and critical care medicine. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1394–1404. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201512-833FR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones SE, Maddocks M, Kon SS, Canavan JL, Nolan CM, Clark AL, et al. Sarcopenia in COPD: prevalence, clinical correlates and response to pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax. 2015;70:213–218. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maltais F, Decramer M, Casaburi R, Barreiro E, Burelle Y, Debigaré R, et al. ATS/ERS Ad Hoc Committee on Limb Muscle Dysfunction in COPD. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:e15–e62. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vilaró J, Ramirez-Sarmiento A, Martínez-Llorens JM, Mendoza T, Alvarez M, Sánchez-Cayado N, et al. Global muscle dysfunction as a risk factor of readmission to hospital due to COPD exacerbations. Respir Med. 2010;104:1896–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greening NJ, Harvey-Dunstan TC, Chaplin EJ, Vincent EE, Morgan MD, Singh SJ, et al. Bedside assessment of quadriceps muscle by ultrasound after admission for acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:810–816. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201503-0535OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kon SS, Canavan JL, Nolan CM, Clark AL, Jones SE, Cullinan P, et al. The 4-metre gait speed in COPD: responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1298–1305. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00088113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spruit MA, Polkey MI, Celli B, Edwards LD, Watkins ML, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study investigators. Predicting outcomes from 6-minute walk distance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:291–297. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Man WD, Polkey MI, Donaldson N, Gray BJ, Moxham J. Community pulmonary rehabilitation after hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: randomised controlled study. BMJ. 2004;329:1209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38258.662720.3A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seymour JM, Moore L, Jolley CJ, Ward K, Creasey J, Steier JS, et al. Outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation following acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax. 2010;65:423–428. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.124164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allaire J, Maltais F, Doyon JF, Noël M, LeBlanc P, Carrier G, et al. Peripheral muscle endurance and the oxidative profile of the quadriceps in patients with COPD. Thorax. 2004;59:673–678. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.020636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gosselink R, Troosters T, Decramer M. Distribution of muscle weakness in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2000;20:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Man WD, Soliman MG, Nikoletou D, Harris ML, Rafferty GF, Mustfa N, et al. Non-volitional assessment of skeletal muscle strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2003;58:665–669. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.8.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:53–59. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Almdal T, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Andersen T, et al. Body mass, fat-free body mass, and prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a random population sample: findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:79–83. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-969OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrikrishna D, Patel M, Tanner RJ, Seymour JM, Connolly BA, Puthucheary ZA, et al. Quadriceps wasting and physical inactivity in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1115–1122. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Bool C, Rutten EP, Franssen FM, Wouters EF, Schols AM. Antagonistic implications of sarcopenia and abdominal obesity on physical performance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:336–345. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00197314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spruit MA, Pitta F, McAuley E, ZuWallack RL, Nici L. Pulmonary rehabilitation and physical activity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:924–933. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0929CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gagnon P, Lemire BB, Dubé A, Saey D, Porlier A, Croteau M, et al. Preserved function and reduced angiogenesis potential of the quadriceps in patients with mild COPD. Respir Res. 2014;15:4. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Borst B, Koster A, Yu B, Gosker HR, Meibohm B, Bauer DC, et al. Is age-related decline in lean mass and physical function accelerated by obstructive lung disease or smoking? Thorax. 2011;66:961–969. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hopkinson NS, Tennant RC, Dayer MJ, Swallow EB, Hansel TT, Moxham J, et al. A prospective study of decline in fat free mass and skeletal muscle strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res. 2007;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puthucheary ZA, Rawal J, McPhail M, Connolly B, Ratnayake G, Chan P, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. JAMA. 2013;310:1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, Wolfe R, Evans WJ. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA. 2007;297:1772–1774. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.16.1772-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner RE, Brunker LB, Agergaard J, Barrows KM, Briggs RA, Kwon OS, et al. Age-related differences in lean mass, protein synthesis and skeletal muscle markers of proteolysis after bed rest and exercise rehabilitation. J Physiol. 2015;593:4259–4273. doi: 10.1113/JP270699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruparel M, Lopez-Campos JL, Castro-Acosta A, Hartl S, Pozo-Rodriguez F, Roberts CM. Understanding variation in length of hospital stay for COPD exacerbation: European COPD audit. ERJ Open Res. 2016;2:00034–2015. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00034-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, Spruit MA, Decramer M, Gosselink R. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2006;129:536–544. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alahmari AD, Kowlessar BS, Patel AR, Mackay AJ, Allinson JP, Wedzicha JA, et al. Physical activity and exercise capacity in patients with moderate COPD exacerbations. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:340–349. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01105-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeBlanc AD, Schneider VS, Evans HJ, Pientok C, Rowe R, Spector E. Regional changes in muscle mass following 17 weeks of bed rest. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1992:2172–2178. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.73.5.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spruit MA, Gosselink R, Troosters T, Kasran A, Gayan-Ramirez G, Bogaerts P, et al. Muscle force during an acute exacerbation in hospitalised patients with COPD and its relationship with CXCL8 and IGF-I. Thorax. 2003;58:752–756. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.9.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burtin C, Ter Riet G, Puhan MA, Waschki B, Garcia-Aymerich J, Pinto-Plata V, et al. Handgrip weakness and mortality risk in COPD: a multicentre analysis. Thorax. 2016;71:86–87. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lauretani F, Bautmans I, De Vita F, Nardelli A, Ceda GP, Maggio M. Identification and treatment of older persons with sarcopenia. Aging Male. 2014;17:199–204. doi: 10.3109/13685538.2014.958457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cote CG, Dordelly LJ, Celli BR. Impact of COPD exacerbations on patient-centered outcomes. Chest. 2007;131:696–704. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nyberg A, Saey D, Maltais F. Why and how limb muscle mass and function should be measured in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1269–1277. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201505-278PS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snider JT, Jena AB, Linthicum MT, Hegazi RA, Partridge JS, LaVallee C, et al. Effect of hospital use of oral nutritional supplementation on length of stay, hospital cost, and 30-day readmissions among Medicare patients with COPD. Chest. 2015;147:1477–1484. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agustí A, Edwards LD, Rennard SI, MacNee W, Tal-Singer R, Miller BE, et al. Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) Investigators. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: a novel phenotype. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creutzberg EC, Casaburi R. Endocrinological disturbances in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;46:76s–80s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00004610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schols AM, Ferreira IM, Franssen FM, Gosker HR, Janssens W, Muscaritoli M, et al. Nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD: a European Respiratory Society statement. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:1504–1520. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00070914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vermeeren MA, Schols AM, Wouters EF. Effects of an acute exacerbation on nutritional and metabolic profile of patients with COPD. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:2264–2269. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10102264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creutzberg EC, Wouters EF, Vanderhoven-Augustin IM, Dentener MA, Schols AM. Disturbances in leptin metabolism are related to energy imbalance during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:1239–1245. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9912016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kythreotis P, Kokkini A, Avgeropoulou S, Hadjioannou A, Anastasakou E, Rasidakis A, et al. Plasma leptin and insulin-like growth factor I levels during acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA, MacCallum PK, Paul EA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are accompanied by elevations of plasma fibrinogen and serum IL-6 levels. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wouters EF. Local and systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:26–33. doi: 10.1513/pats.200408-039MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crul T, Spruit MA, Gayan-Ramirez G, Quarck R, Gosselink R, Troosters T, et al. Markers of inflammation and disuse in vastus lateralis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37:897–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jagoe RT, Engelen MP. Muscle wasting and changes in muscle protein metabolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;46:52s–63s. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00004608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundby C, Calbet JA, Robach P. The response of human skeletal muscle tissue to hypoxia. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3615–3623. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0146-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brody LR, Pollock MT, Roy SH, De Luca CJ, Celli B. pH-induced effects on median frequency and conduction velocity of the myoelectric signal. J Appl Physiol. 1985;1991:1878–1885. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.5.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gertz I, Hedenstierna G, Hellers G, Wahren J. Muscle metabolism in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease and acute respiratory failure. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1977;52:396–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shields GS, Coissi GS, Jimenez-Royo P, Gambarota G, Dimber R, Hopkinson NS, et al. Bioenergetics and intermuscular fat in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-associated quadriceps weakness. Muscle Nerve. 2015;51:214–221. doi: 10.1002/mus.24289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schiavo A, Renis M, Polverino M, Iannuzzi A, Polverino F. Acid-base balance, serum electrolytes and need for non-invasive ventilation in patients with hypercapnic acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease admitted to an internal medicine ward. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:23. doi: 10.1186/s40248-016-0063-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Terzano C, Di Stefano F, Conti V, Di Nicola M, Paone G, Petroianni A, et al. Mixed acid-base disorders, hydroelectrolyte imbalance and lactate production in hypercapnic respiratory failure: the role of noninvasive ventilation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fiaccadori E, Del Canale S, Arduini U, Antonucci C, Coffrini E, Vitali P, et al. Intracellular acid-base and electrolyte metabolism in skeletal muscle of patients with chronic obstructive lung disease and acute respiratory failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 1986;71:703–712. doi: 10.1042/cs0710703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiaccadori E, Coffrini E, Fracchia C, Rampulla C, Montagna T, Borghetti A. Hypophosphatemia and phosphorus depletion in respiratory and peripheral muscles of patients with respiratory failure due to COPD. Chest. 1994;105:1392–1398. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.5.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease 2017 Report: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:557–582. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gayan-Ramirez G, Decramer M. Mechanisms of striated muscle dysfunction during acute exacerbations of COPD. J Appl Physiol. 1985;2013:1291–1299. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00847.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gayan-Ramirez G, Vanderhoydonc F, Verhoeven G, Decramer M. Acute treatment with corticosteroids decreases IGF-1 and IGF-2 expression in the rat diaphragm and gastrocnemius. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:283–289. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9803021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dirks-Naylor AJ, Griffiths CL. Glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis and cellular mechanisms of myopathy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;117:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saudny-Unterberger H, Martin JG, Gray-Donald K. Impact of nutritional support on functional status during an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:794–799. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9612102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hopkinson NS, Man WD, Dayer MJ, Ross ET, Nickol AH, Hart N, et al. Acute effect of oral steroids on muscle function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:137–142. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00139003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costi S, Crisafulli E, Degli Antoni F, Beneventi C, Fabbri LM, Clini EM. Effects of unsupported upper extremity exercise training in patients with COPD: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2009;136:387–395. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Scharplatz M, Troosters T, Walters EH, Steurer J. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD005305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, ZuWallack R, Nici L, Rochester C, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force on Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greening NJ, Williams JE, Hussain SF, Harvey-Dunstan TC, Bankart MJ, Chaplin EJ, et al. An early rehabilitation intervention to enhance recovery during hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic respiratory disease: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2014;349:g4315. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morris PE, Berry MJ, Files DC, Thompson JC, Hauser J, Flores L, et al. Standardized Rehabilitation and hospital length of stay among patients with acute respiratory failure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:2694–2702. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zanotti E, Felicetti G, Maini M, Fracchia C. Peripheral muscle strength training in bed-bound patients with COPD receiving mechanical ventilation: effect of electrical stimulation. Chest. 2003;124:292–296. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ambrosino N, Venturelli E, Vagheggini G, Clini E. Rehabilitation, weaning and physical therapy strategies in chronic critically ill patients. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:487–492. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00094411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maddocks M, Nolan CM, Man WD, Polkey MI, Hart N, Gao W, et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation to improve exercise capacity in patients with severe COPD: a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:27–36. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deacon SJ, Vincent EE, Greenhaff PL, Fox J, Steiner MC, Singh SJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of dietary creatine as an adjunct therapy to physical training in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:233–239. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1508OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Marinari S, Manigrasso MR, De Benedetto F. Effects of nutraceutical diet integration, with coenzyme Q10 (Q-Ter multicomposite) and creatine, on dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and quality of life in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8:40. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-8-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cielen N, Heulens N, Maes K, Carmeliet G, Mathieu C, Janssens W, et al. Vitamin D deficiency impairs skeletal muscle function in a smoking mouse model. J Endocrinol. 2016;229:97–108. doi: 10.1530/JOE-15-0491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jackson AS, Shrikrishna D, Kelly JL, Kemp SV, Hart N, Moxham J, et al. Vitamin D and skeletal muscle strength and endurance in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:309–316. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00043112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Creutzberg EC, Schols AM. Anabolic steroids. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 1999;2:243–253. doi: 10.1097/00075197-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Creutzberg EC, Wouters EF, Mostert R, Pluymers RJ, Schols AM. A role for anabolic steroids in the rehabilitation of patients with COPD? A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Chest. 2003;124:1733–1742. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yeh SS, DeGuzman B, Kramer T M012 Study Group. Reversal of COPD-associated weight loss using the anabolic agent oxandrolone. Chest. 2002;122:421–428. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Casaburi R, Bhasin S, Cosentino L, Porszasz J, Somfay A, Lewis MI, et al. Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:870–878. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-617OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dalton JT, Barnette KG, Bohl CE, Hancock ML, Rodriguez D, Dodson ST, et al. The selective androgen receptor modulator GTx-024 (enobosarm) improves lean body mass and physical function in healthy elderly men and postmenopausal women: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dobs AS, Boccia RV, Croot CC, Gabrail NY, Dalton JT, Hancock ML, et al. Effects of enobosarm on muscle wasting and physical function in patients with cancer: a double-blind, randomised controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:335–345. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70055-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Weisberg J, Wanger J, Olson J, Streit B, Fogarty C, Martin T, et al. Megestrol acetate stimulates weight gain and ventilation in underweight COPD patients. Chest. 2002;121:1070–1078. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ju CR, Chen RC. Serum myostatin levels and skeletal muscle wasting in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2012;106:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cohen S, Nathan JA, Goldberg AL. Muscle wasting in disease: molecular mechanisms and promising therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:58–74. doi: 10.1038/nrd4467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Polkey M, Rooks D, Franssen F, Singh D, Steiner M, Casaburi R, et al. Anabolic treatment of COPD-associated skeletal muscle wasting with bimagrumab; results of a phase IIa double-blind RCT [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A3559. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Padhi D, Higano CS, Shore ND, Sieber P, Rasmussen E, Smith MR. Pharmacological inhibition of myostatin and changes in lean body mass and lower extremity muscle size in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1967–E1975. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Takala J, Ruokonen E, Webster NR, Nielsen MS, Zandstra DF, Vundelinckx G, et al. Increased mortality associated with growth hormone treatment in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:785–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909093411102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elijah IE, Branski LK, Finnerty CC, Herndon DN. The GH/IGF-1 system in critical illness. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;25:759–767. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Burdet L, de Muralt B, Schutz Y, Pichard C, Fitting JW. Administration of growth hormone to underweight patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1800–1806. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9704142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pape GS, Friedman M, Underwood LE, Clemmons DR. The effect of growth hormone on weight gain and pulmonary function in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease. Chest. 1991;99:1495–1500. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.6.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Müller TD, Nogueiras R, Andermann ML, Andrews ZB, Anker SD, Argente J, et al. Ghrelin. Mol Metab. 2015;4:437–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nagaya N, Itoh T, Murakami S, Oya H, Uematsu M, Miyatake K, et al. Treatment of cachexia with ghrelin in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:1187–1193. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.White HK, Petrie CD, Landschulz W, MacLean D, Taylor A, Lyles K, et al. Capromorelin Study Group. Effects of an oral growth hormone secretagogue in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1198–1206. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]