Abstract

Purpose

EphA2 receptor is involved in multiple cross-talks with other cellular networks including EGFR, FAK and VEGF pathways, with which it collaborates to stimulate cell migration, invasion and metastasis. Colorectal cancer (CRC) EphA2 overexpression has also been correlated to stem-like properties of cells and tumor malignancy.

We investigated the molecular crosstalk and microRNAs modulation of the EphA2 and EGFR pathways. We also explored the role of EphA2/EGFR pathway mediators as prognostic factors or predictors of cetuximab benefit in CRC patients.

Experimental Design

Gene expression analysis was performed in EphA2high cells isolated from CRC of AOM/DSS murine model by FACS-assisted procedures. Six independent cohorts of patients were stratified by EphA2 expression to determine the potential prognostic role of a EphA2/EGFR signature and its effect on cetuximab treatment response.

Results

We identified a gene expression pattern (EphA2, Efna1, EGFR, Ptpn12, Atf2) reflecting the activation of EphA2 and EGFR pathways and a coherent dysregulation of mir-26b and mir-200a.

Such pattern showed prognostic significance in stage I-III CRC patients, in both univariate and multivariate analysis. In patients with stage IV and WT KRAS, EphA2/Efna1/EGFR gene expression status was significantly associated with poor response to cetuximab treatment. Furthermore, EphA2 and EGFR overexpression showed a combined effect relative to cetuximab resistance, independently from KRAS mutation status.

Conclusions

These results suggest that EphA2/Efna1/EGFR genes, linked to a possible control by mir-200a and mir-26b, could be proposed as novel CRC prognostic biomarkers. Moreover, EphA2 could be linked to a mechanism of resistance to cetuximab alternative to KRAS mutations.

Keywords: EphA2, EGFR, colorectal cancer, prognostic markers, cetuximab

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer mortality worldwide (1) and among the four most commonly diagnosed cancers in women and men in USA in 2015 (2).

Over the past two decades, an improvement in overall survival in CRC patients has been achieved due to the introduction of the new cytotoxic agents oxaliplatin and irinotecan and the integration of targeted treatments, as the bevacizumab and the cetuximab which interfere with the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), respectively (3).

From the early studies conducted mainly in heavily pretreated chemotherapy-refractory patients and also in chemotherapy-naïve patients with metastatic CRC (mCRC), it became clear that only 10% to 20% of patients with mCRC clinically benefited from anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (moAbs) (4). Such variability in treatment response could be ascribed to the CRC molecular heterogeneity, as recently investigated by several studies (5).

The recognition of the key role of cancer cell heterogeneity in tumor initiation and progression represented the basis for the formulation of the cancer stem cell (CSC) hypothesis, which has been widely accepted to be responsible of cancer spreading and recurrence (6). Recent studies concurred in concluding that the expression of stem cell and mesenchymal genes in CRC cells is associated with poor patient outcome in CRC (7), consequently this stem-like/mesenchymal CRC subtype represents a particular class of highly aggressive CRCs.

A ten-years history of studies showed how cell distribution along the intestinal crypt axis is not casual, but is guided by the bound between Eph receptors and their respective ephrin ligands. In the intestine, EphB2 and EphA2 are two of the most studied Eph receptors. They have opposite distribution and role along the crypt. EphB2high cells, recently identified as intestinal stem cells (ISCs), are restricted to the normal crypt base thanks to the down-regulation, by Wnt signaling, of ephrinB1 expression (8). Loss of EphB2 expression is associated with cancer progression (9). Conversely, EphA2high cells in normal mucosa are positioned at the top of the crypt, where differentiated cells lie, with E-cadherin limiting EphA2 expression at epithelial cell junctions. In CRC, loss of E-cadherin and ligand-independent phosphorylation of EphA2 lead to broader expression and greater activation of the receptor, promoting cell detachment and metastasis (10).

Interestingly EphA2 has been found to be involved, with its ligand-independent activity, in multiple cross-talks with other cellular molecular networks including EGFR, FAK and VEGF pathways (11), with which it collaborates to stimulate migration, invasion and metastasis (12,13). EphA2 is an attractive therapeutic target because of its diverse roles in cancer growth and progression (14). Furthermore, two recent clinical studies on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and CRC patients suggested a role for EphA2 in responsiveness to cetuximab-based targeted therapy (15,16). A preclinical study on lung cancer also defined a role for EphA2 in the maintenance of cell survival of tyrosine kinase (TKI)-resistant, EGFR-mutant cells and indicated that EphA2 may serve as a useful therapeutic target in TKI-resistant tumors (17).

On this ground, with the aim of elucidating new molecular processes contributing to CRC pathogenesis and drug resistance we characterized representative cell subpopulations with stem/differentiation-like features purified from murine CRC and normal colon mucosa, based on the differential expression of EphB2 and EphA2 receptors. We made use of the chemically-induced AOM/DSS murine model of sporadic colon carcinogenesis taking advantage of its high reproducibility and ability to recapitulate, within a predictable time line, colorectal lesions distinctive of human CRC development (18,19).

Significantly, adenocarcinoma EphA2high sorted cells displayed an increased expression of the stemness gene Ascl2 along with a decreased expression level of differentiation gene Krt20 in association with EGFR overexpression.

Since resistance to cetuximab, associated either to a prolonged usage or to an intrinsic genetic heterogeneity, remains the most critical issue in treating CRC, we investigated the crosstalk existing between EphA2 and EGFR pathway genes and its involvement in cancer progression and response to therapy. We characterized the expression levels of relevant EphA2/EGFR pathway targets (EphA2, Efna1, EGFR, Ptpn12, Pi3k, Akt Atf2, mir-200a and mir-26b) in EphA2 sorted cell subpopulations and in public datasets of genomic data derived from multiple cohorts of CRC patients in order to assess their prognostic role and predictive value for responsiveness to cetuximab.

Materials and Methods

Achievement of the AOM/DSS murine model

The AOM/DSS model was induced in 7-week-old Balb/c male mice following the protocol described in our previous work (18). Two different experiments were performed in order to validate the high reproducibility in terms of types of and timing of the lesions (ACF: IV–V week, microadenoma: IV–V week, adenoma: V–VI week and adenocarcinoma: VIII week).

At the end of the 20th week after the start of the treatment, 10 AOM/DSS-treated mice and 10 untreated control mice were sacrificed and colon tissues were obtained for histological and cytofluorimetric analyses.

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines for laboratory animal care and in adherence with ethical standards (20). The study was approved by the Italian Ministry of Health according to the decree n. 336/2013-B.

Isolation of EphA2 and EphB2 Cell Populations in AOM/DSS murine model

CD45-EpCAM+EphA2high/low and CD45-EpCAM+EphB2high/low cell subpopulations were isolated from colon normal mucosa and tumors of mice euthanized at the end of the 20th week after the start of the treatment (AOM administration). Colons were removed from each mouse, cut longitudinally and flushed with cold PBS. Normal mucosa and the adenocarcinomas were disaggregated and cell subpopulations were directly processed for cell sorting separation by adopting the procedure reported elsewhere (8).

Up to 107 cells were used for the staining with the following mix of antibodies: rat anti-EpCAM-PE (eBioscience, Mab G8.8), rat anti-mouse CD45-FITC (eBioscience, Mab 30-F11), rat anti-mouse EphA2-APC (R&D System, Mab 233720), rat anti-mouse EphB2-APC (R&D Systems, Mab 512012) or appropriate isotype controls. Fixable viability dye eFluor 780 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) was added to identify dead cells and debris.

Stained cells were sorted in a FACS Aria 2.0 (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with the support of the BD FacsDIVA software version 6.1.3 (BD Biosciences, Erembodegem, Belgium). The following selection steps were applied to live cells: first, lymphoid cells were discarded by removing the CD45+ cell population; then, epithelial cells were included by selecting for EpCAM+ staining. Then, different intestinal epithelial cells were selected according to graded EphA2 and EphB2 surface levels.

Normal and tumor CD45-EpCAM+ EphA2high/low and CD45-EpCAM+ EphA2high/low cell subpopulations were sorted and collected in DMEM medium. The percentages of EphA2high/low or EphB2high/low positive cells were defined on the base of the Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) control stain strategy necessary to accurately identify expressing cells in the fully stained sample (21) (Fig. 1C). Briefly, we prepared a sample with all reagents except for those of interest (EphA2 and EphB2). Sorted cells were centrifuged and cell pellets were resuspended in Trizol® Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and stored at −80°C for RNA extraction. Authentication of cell subpopulations was performed by qPCR analysis in order to test the gene expression levels of EphA2 and EphB2 and stemness/differentiation genes (Lgr5, Ascl2, and Krt20).

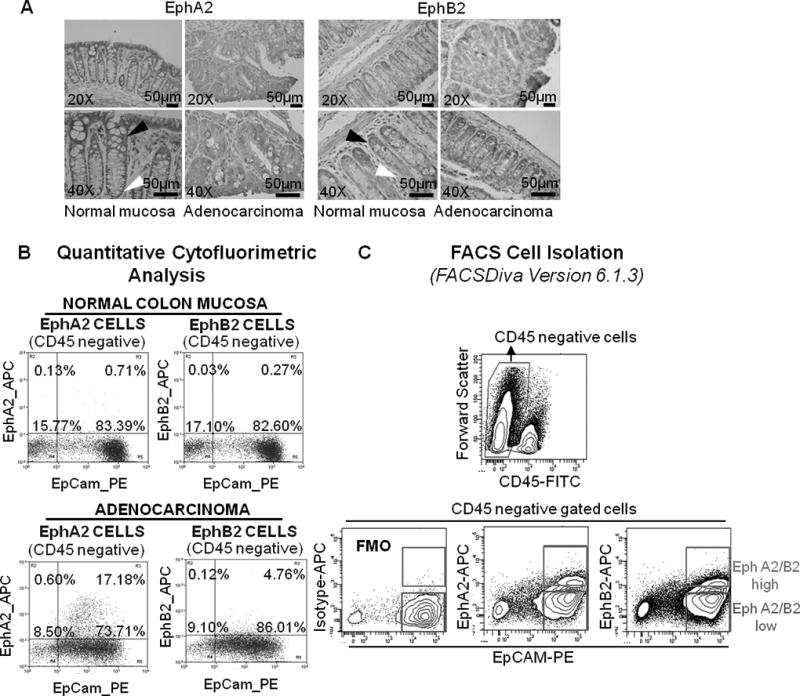

Figure 1.

Isolation of mouse colorectal cell populations based on EphA2 and EphB2 expression. (A) IHC analysis on normal colorectal tissue of control untreated mice demonstrated maximum EphA2 and EphB2 expression in crypt apical columnar cells (white arrowhead) and basal crypt compartment (black arrowhead), respectively; adenocarcinoma shows a diffuse staining for both EphA2 and EphB2 (20× and 40× magnification). (B) Flow cytometry of crypt cells stained for EphA2 revealed an increase of EphA2high cell subpopulation in adenocarcinoma with respect to normal mucosa. EphB2high cells were poorly represented in normal mucosa and colon adenocarcinoma. (C) Representative cell sorting strategy. EphA2high and EphA2low cells as well as EphB2high and EphB2low subpopulations were sorted after gating for CD45- and EpCAM+ staining to ensure epithelial identity. Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) control stain strategy was used to accurately identify EphA2 and EphB2 expressing cells in the fully stained sample.

Total RNA extraction and molecular analysis in murine sorted cells

RNA was isolated using Trizol® Reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions and retrotranscribed using the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Q-PCR analyses were performed using the Taqman® Gene Expression Master Mix and TaqMan assays obtained from Applied Biosystems (Supplementary Fig. 1). Data were analyzed using SDS software 2.3 (Applied Biosystems). Relative expression was calculated according to the method of Fold Change (2^-(DeltaDelta CT)). Hprt1 and Hmbs normalized data gave comparable results, similarly for U6snRNA and SnoRNA202 normalized data of microRNAs. Student-T test was used to analyze the Q-PCR results.

Histopathological analysis and immunohistochemistry of murine tissue samples

Part of the tumor masses and normal colon mucosae were analyzed according to standard histochemical procedures. Mouse adenocarcinoma were diagnosed according to the histopathological criteria described by Boivin et al. (22).

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4-µm-thick FFPE tissue sections after antigen retrieval with sodium citrate buffer. Goat anti-mouse Krt20 and Lgr5, rabbit anti-mouse EphA2 and EphB2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, 1:50) were used. The immunostained slides were observed under a microscope, and the image data were analysed using NIS FreeWare 2.10 software (Nikon, Japan).

Selection of CRC patient cohorts and genomic data from TCGA and GEO datasets

The analysis of the genes and microRNAs of interest was carried out on a multi-study microarray database of CRC expression profiles (total n = 1171) based on the Affymetrix U133 Gene Chip microarray platform. According to Lee et al. (23), five different CRC cohorts were assembled in the database and microarray data and clinical annotations were obtained from the GEO public data repository.

Cohort 1 - patients with stage I–III CRC (n = 226). GEO accession number GSE14333 (24). Cohort 2 - patients with stage II–III CRC (n = 130). GEO accession number GSE37892 (11). Cohort 3 - patients with stage I–IV CRC (n = 566). GEO accession number GSE39582 (25). This cohort allowed us to calculate the Disease Free Survival (DFS), meant as the difference between the time of surgery and the time of the first occurrence of death or of cancer recurrence (2,11,24). Cohort 4 - we considered only patients at stage I–III of the disease (n = 125) as done by Lee et al. (23). GEO accession number GSE41258 (26). We considered the “death” event only if related to cancer disease (Cancer Specific Survival, CSS). All the other causes of deaths, i.e., for other or unknown causes, and alive patients were considered “censored” events. Cohort 5 - patients with refractory metastatic CRC (n = 80) that received cetuximab monotherapy in a clinical trial. GEO accession number GSE5851 (27). In the study of this cohort, patient characteristics were available, and the progression-free survival (PFS) duration was defined as the time from study enrollment to disease progression or death (26). Further, KRAS mutation status in cohort 5 was available (exon 2 genomic region) (27).

Gene expression data for a sixth cohort were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov) (28) - patients with stage I–IV CRC (n = 130). We excluded patients having Mucinous Adenocarcinoma. For this study the Overall Survival (OS) is available, i.e. the time from study enrolment to death.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of gene expression data and other statistical analyses were performed in R ver. 3.1.3 (http://www.r-project.org). Raw data from GEO were downloaded by GEOquery and Biobase tools. Patients were dichotomized through maxstat R package, in order to obtain a significant difference between survival values. Prognostic significance was estimated by log-rank tests and plotted as Kaplan–Meier curves. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to evaluate the effect of EphA2, Efna1, EGFR, Ptpn12, Pi3k, Akt and Atf2 signatures on survival, independently of other clinical parameters. When coupled with other gene signatures (e.g., Efna1high/low), the threshold value between EphA2high and EphA2low groups of samples was set to the median expression value of EphA2, because of the extremely unbalanced sample sizes obtained with the maxstat R package. In cohort 5, differences in response of CRC to treatment of cetuximab were verified using the Fisher’s-exact test. Differences of expression between class members were detected by Student T-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Molecular characterization of murine CRC EphA2 and EphB2 cell subpopulations unveil molecular features of differentiation/stemness of EphA2 cells

To characterize two of the different cell types present in the intestinal epithelium, we developed a cell isolation method based on surface expression of EphA2 and EphB2 receptors, which allowed us to isolate cell subpopulations with different levels of differentiation and stemness properties.

Firstly, we analyzed the expression of both the ephrin receptors with IHC on mouse adenocarcinoma and normal mucosa. In the normal colon mucosa EphB2 presented an expression pattern characterized by a decreasing gradient from the crypt base to the top (Fig. 1A) (8). Crypt base columnar cells (ISCs) showed the highest expression of membrane EphB2 (Fig. 1A right, black arrowhead), whereas the transient amplifying cells progressively decreased EphB2 protein levels as they migrated toward the top of crypts. Apical differentiated cells in the villi were negative for EphB2 expression (Fig. 1A right, white arrowhead). Conversely, maximum EphA2 expression was observed in the most differentiated crypt apical cells of the normal colon and a weak staining was shown at the crypt basal level (Fig. 1A left, black and white arrowhead, respectively). Tumor cells displayed a highly heterogeneous and not gradient-disposed staining for both anti-EphA2 and anti-EphB2 antibodies (Fig. 1A).

The cytofluorimetric analysis showed a change in the cellular density of both EphA2 and EphB2 cell populations between the adenocarcinoma and the normal colon mucosa (Fig. 1B). Specifically, an increase of EphA2high cell fraction was measured in adenocarcinoma (17.18%) comparing to normal mucosa (0.71%). Differently, EphB2high cells resulted poorly represented both in the adenocarcinoma (4.76%) and in normal colon mucosa (0.27%).

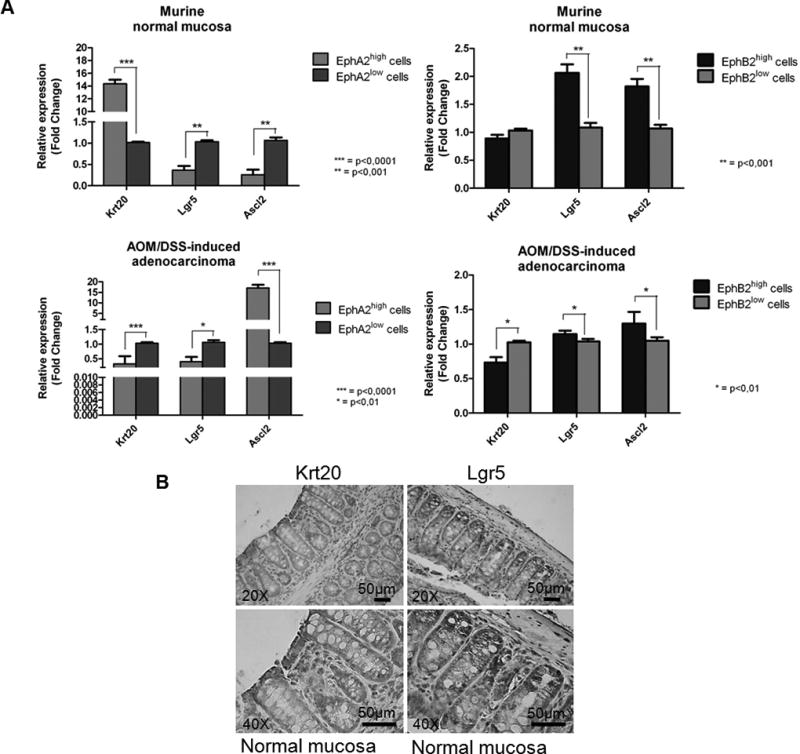

Gene expression analysis in EphB2high cell subpopulations from adenocarcinoma as well as normal mucosa, revealed an upregulation of the stemness-specific genes Lgr5 (8,29) and Ascl2 (8,30) (p<0.001 in normal mucosa; p<0.01 in adenocarcinoma), with a down-modulation of Krt20, a common differentiation marker (8) (p<0.001 in normal mucosa; p=ns (not significant) in adenocarcinoma) (Fig. 2A right).

Figure 2.

(A) Q-PCR analysis of differentiation (Krt20) and stem cell markers (Lgr5, Ascl2) in EphA2high/low and EphB2high/low cell subpopulations purified from murine normal colon and colorectal adenocarcinoma. Data are represented as mean +/− SD. Statistically significant differences were calculated using Student’s T-test: *** p<0.0001; ** p<0.001; * p<0.01. (B) IHC analysis of Krt20 and Lgr5 protein in normal murine colon. Left panels: cells on the top of the crypt were strongly stained for Krt20. Right panels: cells at the crypt bottom were strongly stained for Lgr5 (20× and 40× magnification).

Importantly, a different expression pattern resulted associated to the EphA2high cell population. In normal mucosa, we observed a coherent down-modulation of stemness genes, Lgr5 (p<0.001) and Ascl2 (p<0.001) together with an up-modulation of Krt20 expression level (p<0.0001), suggesting an enrichment of the EphA2high cell population with differentiated cells. In contrast in adenocarcinoma the EphA2high cells displayed a decreased expression levels both of Krt20 (p<0.0001) and Lgr5 (p<0.01) along with an increased expression of Ascl2 (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2A left).

Further this expression pattern was confirmed by IHC analysis which showed an overlapping staining between Krt20 and EphA2 at the apical level of crypts in the normal mucosa samples and between Lgr5 and EphB2 cells at the basal level (Fig. 1A and 2B).

Expression levels of EGFR/EphA2 signaling effectors are dysregulated in murine CRC EphA2high cell populations

The molecular analysis in CRC EphA2high and EphB2low cells revealed a significant dysregulation of the expression levels of EphA2 and its ligand ephrinA1 (Efna1) as well as the perturbation of gene transcriptional levels of EGFR signaling downstream players in adenocarcinomas (Fig. 3A, B). These results provide new evidences that the CRC EphA2 cell signaling involves the dysregulation of EGFR effectors.

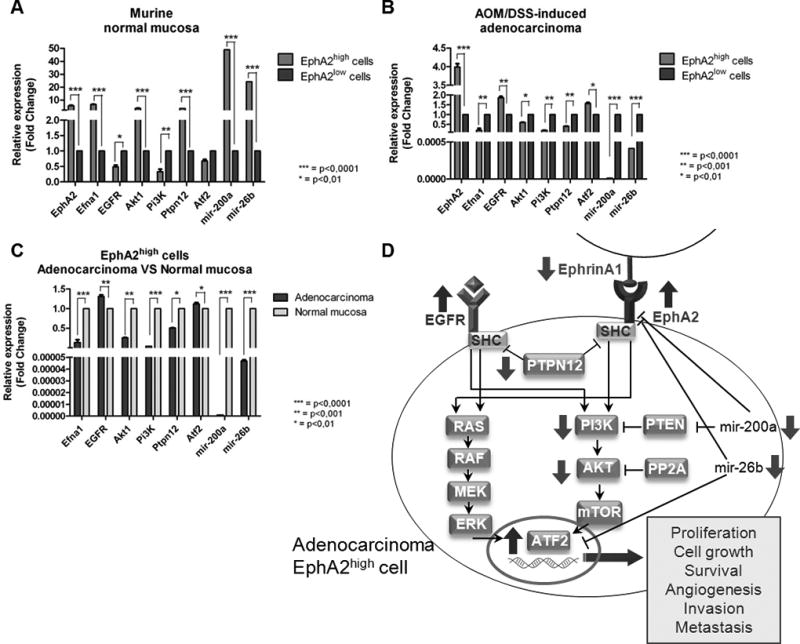

Figure 3.

Q-PCR analysis of EGFR signaling effectors in EphA2 cell subpopulations of murine CRC. Data are represented as mean +/− SD. Statistically significant differences were calculated using Student’s t-test: *** p<0.0001; ** p<0.001; * p<0.01. Gene expression levels in EphA2high and EphA2low cell subpopulations of (A) normal mucosa and (B) adenocarcinoma. (C) Gene expression levels in EphA2high subpopulation of adenocarcinoma and EphA2high subpopulation of normal colic mucosa. (D) Schematic representation of the dysregulation of EphA2/EGFR pathways crosstalk in adenocarcinoma EphA2high cell.

The analysis of the following genes of interest in EphA2high cells of adenocarcinoma versus normal colon mucosa showed a peculiar pattern of gene expression involving the down-modulation of Efna1 (p<0.0001) as well as a slight over-expression of Egfr (p<0.001), a marked down-modulation of Ptpn12 (p<0.01), Akt (p<0.001), and Pi3k (p<0.0001), and an up-modulation of Atf2 (p<0.0001). The expression levels of mir-200a and mir-26b were both decreased (p<0.0001, and p<0.0001, respectively) (Fig. 3C), with an inverse correlation respect to their target (EphA2 and Atf2) gene expression levels.

Such expression pattern of genes belonging to EphA2 and EGFR pathways (Fig. 3D) was subsequently investigated in clinical sample cohorts to assess an association with CRC disease.

EphA2 and EphA2/EGFR downstream genes have prognostic significance in CRC patients

We examined the correlation of EphA2 gene expression with the clinical characteristics of CRC patients included in six cohorts of public microarray dataset (Supplementary Fig. 2). We found that 10% to 47.2% of the patients in the six cohorts had a high expression of EphA2 gene. Also we analyzed the correlation of clinical characteristics of patients with the EphAhigh gene expression level (Supplementary Fig. 3). We excluded cohort 5 since consisted of patients with only stage IV CRC. Although EphA2high patients apparently had a more advanced disease than did EphA2low patients in cohort 1 and cohort 4 (p=ns), we did not see a clear difference in stage distribution between the two groups of patients in the other cohorts. Interestingly, in the cohort 3 we observed a slightly higher percentage of KRAS wild type (WT) in EphA2low patients than in EphA2high patients (p=0.02). Finally, we found no differences in other clinical variables between EphA2high and EphA2low patients groups (Supplementary Fig. 3).

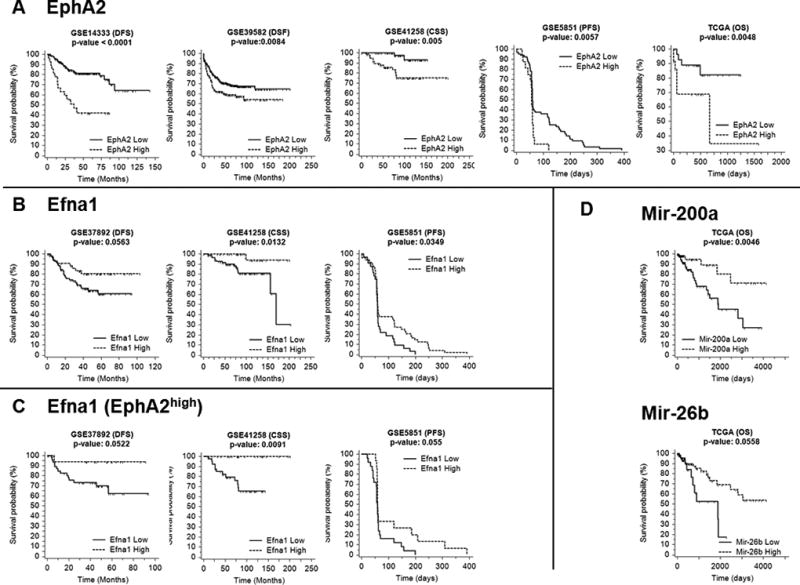

We then investigated the prognostic impact of EphA2 gene upregulation analyzing data of patients with stage I–III CRC (cohort 1 and 3) (Fig. 4A). Tumor recurrence and DFS data were available for these two cohorts. We also analyzed CSS data for cohort 4 since DFS data were not available for this group. Kaplan-Meier curves significantly showed much worse survival durations in EphA2high patients than in EphA2low patients (Fig. 4A), indicating that the upregulation of EphA2 gene expression is related to poor prognosis for CRC. This result was confirmed also in cohort 5 and 6. Additionally, down-modulation of Efna1 had a prognostic impact evaluating both all patients and EphA2high CRC patients (Fig. 4B, C). Moreover, Kaplan-Meier curves for EphA2high patients showed a possible prognostic role also for Ptpn12, Pi3k, and Atf2 (Supplementary Fig.4). The down-modulation of Akt gene expression in EphA2high CRC patients did not show a significant prognostic role for such gene (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of (A) EphA2high (dashed line) versus EphA2low (solid line) for cohort 1, 3, 4, 5 and 6 (B) Efna1high (dashed line) versus Efna1low (solid line) for cohort 2, 4 and 5. (C) Analysis of Efna1 conducted only for patients belonging to EphA2high group for the same cohorts of B. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival curves on TCGA dataset of mir-200ahigh (dashed line) versus mir-200alow (solid line) and mir-26bhigh (dashed line) versus mir-26blow (solid line). Expression value thresholds were determined through maxstat R package. P-values were calculated using log-rank tests. Tick marks represent censored data.

Interestingly, a significantly worse survival duration (DFS) was associated with elevated EGFR gene expression for all patients and for patients stratified for EphA2 high expression level (Supplementary Fig. 5). The hazard ratio (HR) values resulted statistically significant for the cohorts 1 [HR, 2.7152; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.26–5.84] and 3 [HR, 2.0696; 95% CI, 1.02–4.19], meaning that patients with high expressions of EGFR and EphA2 die at twice (and more) the rate per month as the EphA2 high patients with EGFRlow.

Kaplan-Meier curves for mir-200a and mir-26b were calculated considering all patients of TCGA dataset, not stratified for EphA2 gene expression levels, because gene and microRNA expression data were not available for the same set of subjects. Coherently to what has been shown previously in this analysis we confirmed the prognostic impact of mir-200a in CRC. Noteworthy a reduced expression of mir-26b was related to a decreased OS in patient with CRC (Fig. 4D).

We conducted further analyses to determine whether the prognostic impact of the EphA2 gene expression pattern is independent of other clinical variables. We pooled the patients in cohorts 1, 2 and 3 with available DFS data (n = 853) for univariate and multivariate analyses of factors affecting DFS (Table 1). In the multivariate analysis, EphA2high status was related to worse DFS rates than was EphA2low [HR, 1.47; 95% CI 1.10–1.96; p=0.0095] independently of other clinical variables (Table 1A).

Table 1.

| A - Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors affecting DFS in stage I–III patients (patients data from the cohorts 1 to 3 were pooled together. N = 853) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Univariate analysisa | Multivariate analysisb | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Variables | N | 5-Years DFS | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Agec | ||||||

| <70 y | 447 | 68.50% | – | – | – | – |

| >= 70 y | 405 | 74.60% | 0.1518 | – | – | – |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 388 | 75.20% | 0.0758 | 0.7539 | 0.58–0.98 | 0.0386 |

| Male | 465 | 68% | – | – | – | – |

| Location | 0.5376 | |||||

| Left | 462 | 69.30% | – | – | – | – |

| Rectum | 30 | 77.50% | – | – | – | – |

| Right | 358 | 73.30% | – | – | – | – |

| Unknown | 3 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.0002 | |||||

| Done | 289 | 64.40% | – | 0.9553 | 0.69–1.32 | 0.7838 |

| Undone | 433 | 77.30% | – | 1 | ||

| Unknown | 131 | 67.90% | – | 1.0719 | 0.72–1.6 | 0.7734 |

| Stage | <0.0001 | |||||

| I | 77 | 95.40% | – | 0.2092 | 0.07–0.66 | 0.00081 |

| II | 427 | 79.10% | – | 1 | ||

| III | 349 | 57.10% | – | 2.5309 | 1.86–3.44 | <0.0001 |

| EphA2 Expression | ||||||

| High | 196 | 63.70% | 0.0041 | 1.4697 | 1.01–1.96 | 0.0095 |

| Low | 657 | 73.60% | – | 1 | – | – |

| B - Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors affecting PFS in patients who received Cetuximab monotherapy (cohort 5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Univariate analysisa | Multivariate analysisb | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Variables | N | PFS (median) | P-value | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| Agec | ||||||

| <70 y | 54 | 59 | – | – | – | – |

| >= 70 y | 24 | 60 | 0.227 | – | – | – |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 44 | 58 | 1.7653 | 1.04–2.99 | 0.035 | |

| Male | 36 | 61 | 0.009 | 1 | – | – |

| EphA2 Expression | ||||||

| High | 16 | 57 | 0.006 | 1.5101 | 0.75–3.04 | 0.2513 |

| Low | 64 | 60 | – | 1 | – | – |

| KRAS Mutationd | ||||||

| Mutant | 27 | 59 | – | 1.3012 | 0.75–2.26 | 0.3521 |

| WT | 43 | 61 | 0.142 | 1 | – | – |

In univariate analyses, log-rank tests were conducted.

In the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, only variables with P < 0.15 in univariate analysis were included and the "enter method" was applied.

Data on age of one patient were missing.

In univariate analyses, log-rank tests were conducted.

In the multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, only variables with P < 0.15 in univariate analysis were included and the "enter method" was applied.

Data on age of 2 patients were missing.

Data on KRAS mutational status of 10 patients were missing.

Furthermore, the univariate analysis only in CRC patients with EphA2high status, belonging to cohorts 1, 2 and 3, showed a significant statistical association with the disease stage (p<0.0001) and the adjuvant chemotherapy (p=0.042). Moreover, the percentage of up/down-expression of EGFR, Ptpn12 and Atf2 associated to EphA2high status followed the same trend of our preclinical expression results, although Atf2 did not reach statistical significance (Supplementary Tab. 1).

Additionally, the multivariate analysis showed that EGFRhigh is related to worse DFS rates than was EGFRlow [HR, 1.81; 95% CI 1.24–2.66; p=0.0024], while opposite results were observed for Pik3CG, i.e. the lower Pik3CG, the worse the DFS [HR, 1.68; 95% CI 1.15–2.47; p=0.0083]. In this regard, this conclusion was reached by the analysis of only cohort 1 and 3, because the second cohort did not profile this gene. Efna1 and Ptpn12 resulted not significant by multivariate analyses (Supplementary Tab. 1).

These findings may suggest that the prognostic relevance of EphA2 (alone or in combination with Efna1, Ptpn12 and EGFR gene expression status) in CRC patients is maintained even when taking into account the classic clinical prognostic features.

EphA2/Efna1/EGFR gene expression status is significantly associated with poor response to cetuximab treatment in CRC patients

Only the patients in cohort 5 (n=80) received cetuximab monotherapy. In the 70 patients of this cohort who had KRAS mutation status data available, we observed no difference in the KRAS mutation rates between the EphA2high and EphA2low patients groups (Supplementary Tab. 2A). However, we did notice differences in response to cetuximab between the two groups (Fig. 5A). Specifically, complete remission or partial remission occurred only in the EphA2low group [response rate: 11.11% (EphA2low) vs. 0.0% (EphA2high); p=0.33], and the disease control rate was significantly higher in the EphA2low group than in the EphA2high group (44.44% vs. 7.14%; p=0.012) (Supplementary Tab. 2B and 2C). We then restricted our analysis to WT KRAS patients: partial remission occurred only in EphA2low group [response rate: 15.15% (EphA2low) vs. 0.0% (EphA2high); p=0.574] and also for the disease control rate only EphA2low patients showed partial remission or stable disease [disease control rate: 60.61% (EphA2low) vs. 0.0% (EphA2high); p=0.008] (Supplementary Tab. 2D and 2E).

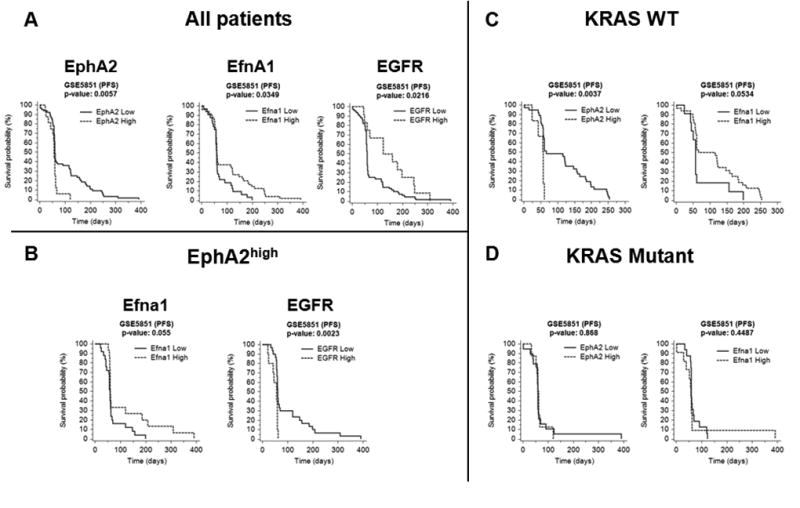

Figure 5.

(A) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of EphA2, Efna1 and EGFR for cohort 5. Survival curves of EphA2high (dashed line) versus EphA2low (solid line), Efna1high (dashed line) versus Efna1low (solid line) and EGFRhigh (dashed line) versus EGFRlow (solid line) for all patients of the cohort. P-values were calculated using log-rank tests. Expression value thresholds for determining high and low groups were determined through maxstat R package. (B) Analysis of Efna1 and EGFR conducted only for patients belonging to EphA2high group. EphA2high group was determined with EphA2 median expression threshold. (C) Survival curves of EphA2 and Efna1 for patients with WT KRAS. (D) Survival curves of EphA2 and Efna1 for patients with mutant KRAS. P-values were calculated using log-rank tests.

Patients with EphA2high status showed a shorter PFS duration than did EphA2low patients (p=0.0057) (Fig. 5A). An inverse trend in PFS duration was displayed by Efna1high/low patients both in all patients (Fig. 5A) and in EphA2high patients (Fig. 5B) of cohort 5. Finally, it is worth noting that the cetuximab treated patients of the cohort 5 with increased expression of EGFR showed a statistically significant longer duration of PFS comparing to the patients with EGFRlow status (Fig. 5A). However, a marked inversion of the PFS duration trend was observed in patients EGFRhigh and EphA2high (Fig. 5B), suggesting a possible role of EphA2 in bypassing the inhibition of EGFR pathway exerted by cetuximab.

EphA2/Efna1/EGFR gene expression level is not correlated to KRAS genetic status

We further investigated the correlation between EphA2 status and somatic mutations in KRAS gene in patient cohort 5. No significant differences in mutation rate for KRAS were exhibited in the univariate analysis of all patients (Table 1B) neither in only EphA2high patients of cohort 5 (Supplementary Tab. 3).

EGFR, Ptpn12, and Pi3k were significant by univariate analyses, and exhibited a prognostic relevance when associated to gender (p=0.0036, 0.0493, 0.0584 respectively) (Supplementary Tab. 3). Moreover, PFS rate trends are comparable to those of cohorts 1, 2 and 3, described above.

Considering the response to cetuximab treatment in the cohort 5, we observed, as expected, that patients with WT KRAS had a longer PFS duration than patients with KRAS mutations (31), although this correlation did not reach statistical significance (Table 1B).

Furthermore, the PFS of patients with EphA2high status was short considering all patients of cohort 5 (p=0.0057; Fig. 5A) as well as for patients with WT KRAS (p=0.0037; Fig. 5 C). On the contrary, for patients with mutant KRAS, no difference could be detected between the PFS of EphA2high and EphA2low status, although this correlation did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 5D), suggesting that the role of EphA2 in the resistance to cetuximab treatment is independent from the KRAS mutations.

Inversely to the trend of PFS observed for EphA2, Efna1high patients had a significantly longer PFS duration than did Efna1low patients (p=0.0349; Fig. 5 A), more so in WT KRAS patients (p=0.0534; Fig. 5C) than in KRAS-mutant patients (p=0.4487; Fig. 5D) although this correlation did not reach statistical significance. Poor statistical significance of the results described above is due to the small number of patients remaining for the analysis after KRAS status and EphA2/Efna1-dependent stratification.

Discussion

A major issue of this study consisted in defining a coherent molecular picture linked to the down or up-modulation of EphA2/EGFR downstream factors in colorectal carcinogenesis, with the aim to translate potential novel prognostic biomarkers into clinical application. As emerged, even if EphB2 marks a tumor initiating cell population with stem-like features (8) and is a key actor in cancer initiation, it becomes less relevant in cancer progression, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis, where EphA2 plays a critical role (31), in multiple crosstalks with other cellular molecular networks including FAK, VEGF and EGFR pathways (9,10,13).

With this assumption, in this study we isolated, from a murine CRC model, cell subpopulations that homogeneously expressed high or low level of EphA2. In such selected subpopulations we investigated a combination of EphA2/EGFR downstream genes perturbation pattern that was validated in clinical sample cohorts derived from 6 independent public datasets.

In agreement with previous studies (32,33) we have shown, by IHC staining, that a decreasing gradient of EphB2 from the crypt base to the top characterized normal colon mucosa, whereas EphA2 expression was mostly observed in the differentiated compartment of crypt apical columnar cells. Differently than normal tissue, adenocarcinoma displayed a highly heterogeneous and not gradient-disposed staining for both EphB2 and EphA2 proteins and it was enriched in EphA2high cell fractions also showed in the cytofluorimetric analysis. The overexpression of EphA2 has been recently reported in different kinds of solid tumors, included the colon (31,34–37). Conversely, a reduction of EphB2high cell subpopulation was observed in adenocarcinoma. This finding obtained in our preclinical model was in line with data reported elsewhere (8,38).

Notably adenocarcinoma EphA2high tumor cells showed low expression levels both of Krt20 and Lgr5 along with an increased expression of Ascl2 suggesting that the EphA2high cell population in tumors could represent a fraction of cells that underwent dedifferentiation and likely acquired CSC-like properties as supported by other studies in CRC, NSCLC and glioblastoma (17,39,40). We validated expression molecular results with the IHC analysis and we showed an overlap between EphB2+ cells and Lgr5+/Krt20− cells in normal mucosa. Similarly, normal EphA2+ cells resulted Lgr5− and Krt20+.

In the perspective to elucidate the role of EphA2 receptor in CRC, described elsewhere as an important mediator of CRC cell migration/invasion (38), we focused on the signaling crosstalk between EphA2 and EGFR.

EphA2high cells of murine adenocarcinoma showed a down-modulation of the ligand Efna1 as well as a slight over-expression of Egfr, a marked down-modulation of Ptpn12, and an up-modulation of the transcription factor Atf2. The expression profiles of each molecule involved in EphA2/EGFR crosstalk in normal and tumoral cells resulted in reciprocal coherence with each other, supporting the general picture we defined as the basis of this study.

Specifically, in adenocarcinoma EphA2high cells we found the upregulation of the expression of both the receptors tyrosine kinase, EphA2 and Egfr, and a downregulation of the ligand Efna1, which suggest a higher activation of the downstream pathways, respectively, as confirmed by the overexpression of Atf2, a critical target of MAPK activities which are set downstream of EGFR and EphA2 receptor. Such transcriptional factor is responsible of the regulation of growth, survival or apoptosis in tumorigenesis (41).

Little is known about the regulation of EphA2 expression, however it has been demonstrated that the regulation of EphA2 transcription can be also operated by ligand-activated EGFR and by the constitutively active EGFRvIII (13,21). On the other hand, the downregulation of Efna1 suggests the possibility of a ligand-independent mechanism of action of the receptor EphA2 in the EphA2high cells analyzed (42,43).

We also observed a down-modulation of the expression of the tumor suppressor Ptpn12, a tyrosine phosphatase that interacts with and inhibits multiple oncogenic tyrosine kinases, including EphA2 and EGFR (44). Additionally, in cancer EphA2high cells we found down-modulated two important downstream components of EGFR pathway: Pi3k and Akt. In this case, Pi3k and Akt functional hyper-activation in CRC is not dependent on transcriptional upregulation, but likely on genetic mutations of the respective genes (45). It must be considered also the number of downstream components which tightly buffer at multiple levels the Pi3k signaling pathway, thereby leading to a complex network of signals (46).

A key finding of our study is that such gene expression pattern obtained in preclinical setting had a reliable prognostic and predictive significance when evaluated in the heterogeneous and complex human tumor, on a large number of CRC patients considering different clinical endpoints (OS, DFS, CSS and PFS).

Analysis of microarray data of six public CRC datasets showed that 10% to 47.2% of the patients had a high expression of EPHA2 gene. This was in line with recent findings based on studies focused on the oncogenic role of EphA2 in CRC and other tumors (31,34,37).

Based on the available clinical outcome data derived from the public datasets we observed much worse survival durations (OS, DFS, CSS and PFS) in EphA2high patients than in EphA2low patients indicating that the upregulation of EphA2 gene expression is related to poor prognosis for CRC. Conversely the decreased expression of the ligand Efna1 was significantly associated with worse survival duration evaluating both all patients and EphA2high CRC patients, sustaining the possibility of a ligand-independent mechanism of action of the receptor EphA2 in tumors (42,43,46). In CRC patients with stage II/III we confirmed that the prognostic role of EphA2 is independent of other clinical variables as shown by the univariate and multivariate analysis. Interestingly increased EGFR gene expression was significantly associated with worse survival duration (DFS) for all patients as well as for stratified EphA2high patients and with an increased HR values in EphA2high cases suggesting that patients with high expressions of both EGFR and EphA2 die at twice the rate per month as the EphA2high patients with EGFRhigh.

We further investigated the prognostic impact of downstream targets of EGFR/EphA2 pathway such as Efna1, Ptpn12, Pi3k, Akt and Atf2 in EphA2high stratified patients and we showed that all these genes, except for Pi3k and Akt, are associated to a worse DFS when dysregulated with the trend observed in the EphA2high cells. Furthermore, the multivariate analysis showed that the prognostic relevance of EphA2 (alone or in combination with EGFR, Efna1, and Ptpn12 status) in CRC patients is independent from classic clinical prognostic features.

The molecular analysis was extended also to the mir-200a and mir-26b which target both EphA2 and EGFR pathways. In EphA2high murine cells sorted from CRC the expression levels of Mir-200a and Mir-26b were both decreased and inversely correlated with the expression levels of their validated targets EphA2 and Atf2, suggesting an epigenetic regulation pattern coherent with the general expression framework object of our study (47,48).

We also found that both mir-200a and mir-26b have a prognostic impact in CRC, confirming a previous study on mir-200a (41) and providing the first evidence that the down-modulation of mir-26b is significantly correlated with poor prognosis in patient with CRC.

Resistance to cetuximab remains one of the most critical issue to treat CRC and up to 40%–60% of patients with WT KRAS tumors do not respond to such therapy. In this perspective we considered relevant to investigate the involvement of EphA2 and downstream targets overlapping EGFR pathway in EphA2-stratified patients in relation to the therapy response and to KRAS mutation status.

Particularly, disease control rate was significantly higher in the EphA2low group than in the EphA2high group which also showed a shorter PFS duration than did EphA2low patients. Consistent with the picture outlined by our molecular results and survival analysis, EphA2high patients displayed a worse outcome. In line with other and well established evidences an increased expression of EGFR was significantly associated with a longer duration of PFS in patients treated with cetuximab, coherently with the role of EGFR as target of this drug (49). Interestingly, patients with an overexpression of EGFR and EphA2 displayed an inverse correlation with clinical outcome (PFS), corroborating the hypothesis that dysregulated expression of EphA2 may overcome the EGFR pathway inhibition exerted by cetuximab.

This observation was in line with recent findings obtained in other studies demonstrating that EphA2 overexpression is involved in the resistance to both EGFR tirosin-kinase inhibitors (TKI) such erlotinib (lung cancer) (17) and vemurafenib (melanoma) (50) and moAbs as trastuzumab (breast cancer) (51). Additionally the EphA2 blockade is proposed as a new strategy to restore the anti-EGFR sensitivity. Collectively, these studies demonstrated the promise and utility of targeting EphA2 to overcome the resistance to anti-EGFR therapy. The EPH is indeed a complex signaling system which impacts RAS–Pi3k–Akt and RAS–RAF-MAPK pathways.

Further in our study EphA2 expression level was not correlated to KRAS mutation status. The PFS of EphA2high patients was short considering all patients as well as for patients with WT KRAS, but not with mutant KRAS suggesting that EphA2 may have a role in the resistance to cetuximab treatment independently from the KRAS mutations.

These results suggest the hypothesis that EphA2 can be linked to a novel mechanism of resistance to cetuximab therapy which can be considered alternative to KRAS mutations. It is known, indeed, that even in patients with WT KRAS, the efficacy of cetuximab therapy is restricted to a small subset of patients and is not sustainable (52). To define the features of patients with metastatic CRC which will respond better to cetuximab treatment is of great relevance.

In conclusion, through a preclinical CRC model and retrospective studies on CRC patients, we identified novel potential prognostic and predictive targets, as EphA2/Efna1/EGFR/Ptpn12/Atf2/mir-200a/mir-26b genes, which could be helpful in selecting CRC patients with poor prognosis and cetuximab resistance. However, since we applied our analysis to retrospective patients cohorts, our results require validation in prospective studies. Functional studies to elucidate the crosstalk of EphA2 with EGFR pathway effectors still remain to be performed.

Since EGFR signaling is one of the most druggable pathway (moAbs and TKIs), this study represents an important advance also for further development of more personalized targeted therapies against CRC which may take advantage of a chemosensitization approach through EphA2 blockade.

Supplementary Material

Translational relevance.

Tumor heterogeneity and the presence of stem-like cells have been identified as key features for resistance to anticancer treatments including targeted therapy. The Eph receptors comprise a large family of receptor tyrosine kinases, that marks stem-like cells in different tissues. In colorectal cancer (CRC) EphA2 overexpression has been linked to stem-like properties of cells and tumor malignancy. We used a strategy to uncover in murine homogeneous tumor EphA2high cell subpopulation, obtained by in vivo FACS-based isolation, a novel potential molecular signature involving EphA2 and EGFR pathways. The pattern incorporates EphA2-linked modulation of mir-26b and mir-200a expression. Such preclinical findings, based on modification of EphA2/Efna1/EGFR pathways, correlated with clinical outcome and strengthened a predictive value for cetuximab responsiveness. Since cetuximab resistance, associated to an intrinsic genetic heterogeneity, remains the most critical issue in treating CRC, this study suggests new potential biomarkers and therapeutically actionable kinase targets in the EphA2/Efna1/EGFR/mir-26b/mir-200a linked pathways.

Acknowledgments

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from Regione Lazio – Progetti Imprenditoriali (ITINERIS 2 to VMF), Italian Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR) national research program and PON02_00576_3329762/3 AMIDERHA to VMF, Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC IG 14368 to ALV) (AIRC MFAG 10520 to MLP), National Institute of Health (P30CA006973 and UL1 TR 001079 to LM).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–230. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375:1030–47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siravegna G, Mussolin B, Buscarino M, Corti G, Cassingena A, Crisafulli, et al. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat Med. 2015;21:795–801. doi: 10.1038/nm.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linnekamp JF, Wang X, Medema JP, Vermeulen L. Colorectal cancer heterogeneity and targeted therapy: a case for molecular disease subtypes. Cancer Res. 2015;75:245–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell stem cell. 2014;14:275–91. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Sousa E, Melo F, Wang X, Jansen M, Fessler E, Trinh A, et al. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat Med. 2013;19:614–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merlos-Suárez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Céspedes MV, Rossell D, et al. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–24. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd AW, Bartlett PF, Lackmann M. Therapeutic targeting of EPH receptors and their ligands. Nat Rev Drug Disc. 2014;13:39–62. doi: 10.1038/nrd4175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herath NI, Boyd AW. The role of Eph receptors and ephrin ligands in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2003–11. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith JJ, Deane NG, Wu F, Merchant NB, Zhang B, Jiang A, et al. Experimentally derived metastasis gene expression profile predicts recurrence and death in patients with colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:958–68. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brantley-Sieders DM, Zhuang G, Hicks D, Fang WB, Hwang Y, Cates JM, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 promotes mammary adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis and metastatic progression in mice by amplifying ErbB2 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:6–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI33154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen AB, Stockhausen MT, Poulsen HS. Cell adhesion and EGFR activation regulate EphA2 expression in cancer. Cellular Signalling. 2010;22:636–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Hu W, Bottsford-Miller J, Liu T, Han HD, Zand B, et al. Cross-talk between EphA2 and BRaf/CRaf is a key determinant of response to Dasatinib. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1846–55. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotoula V, Lambaki S, Televantou D, Kalogera-Fountzila A, Nikolaou A, Markou K, et al. STAT-related profiles are associated with patient response to targeted treatments in locally advanced SCCHN. Transl Oncol. 2011;4:47–58. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strimpakos A, Pentheroudakis G, Kotoula V, De Roock W, Kouvatseas G, Papakostas P, et al. The prognostic role of Ephrin A2 and Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor pathway mediators in patients with advanced colorectal cancer treated with cetuximab. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013;12:267–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amato KR, Wang S, Tan L, Hastings AK, Song W, Lovly CM, et al. EPHA2 Blockade Overcomes Acquired Resistance to EGFR Kinase Inhibitors in Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:305–18. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Robertis M, Massi E, Poeta ML, Carotti S, Morini S, Cecchetelli L, et al. The AOM/DSS murine model for the study of colon carcinogenesis: from pathways to diagnosis and therapy studies. J Carcinog. 2011;10:9. doi: 10.4103/1477-3163.78279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Robertis M, Arigoni M, Loiacono L, Riccardo F, Calogero RA, Feodorova, et al. Novel insights into Notum and glypicans regulation in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:41237–57. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, Balmain A, Bruder G, Chaplin DJ, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;102:1555–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roederer M. Spectral compensation for flow cytometry: visualization artifacts, limitations, and caveats. Cytometry. 2001;45:194–205. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20011101)45:3<194::aid-cyto1163>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boivin GP, Washington K, Yang K, Ward JM, Pretlow T, Russell R, et al. Pathology of mouse models of intestinal cancer: consensus report and recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:762–77. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee KW, Lee SS, Kim SB, Sohn BH, Lee HS, Jang HJ, et al. Significant association of oncogene YAP1 with poor prognosis and cetuximab resistance in colorectal cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:357–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorissen RN, Gibbs P, Christie M, Prakash S, Lipton L, Desai J, et al. Metastasis-associated gene expression changes predict poor outcomes in patients with dukes stage B and C colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7642–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marisa L, de Reyniès A, Duval A, Selves J, Gaub MP, Vescovo L, et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sheffer M, Bacolod MD, Zuk O, Giardina SF, Pincas H, Barany F, et al. Association of survival and disease progression with chromosomal instability: a genomic exploration of colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7131–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902232106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khambata-Ford S, Garrett CR, Meropol NJ, Basik M, Harbison CT, Wu S, et al. Expression of epiregulin and amphiregulin and K-ras mutation status predict disease control in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with cetuximab. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3230–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Cancer Genome Atlas Project. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munoz J, Stange DE, Schepers AG, van de Wetering M, Koo BK, Itzkovitz S, et al. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent '+4' cell markers. The EMBO journal. 2012;31:3079–91. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuijers J, Junker JP, Mokry M, Hatzis P, Koo BK, Sasselli V, et al. Ascl2 acts as an R-spondin/Wnt-responsive switch to control stemness in intestinal crypts. Cell stem cell. 2015;16:158–70. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang WB, Brantley-Sieders DM, Parker MA, Reith AD, Chen J. A kinase-dependent role for EphA2 receptor in promoting tumor growth and metastasis. Oncogene. 2005;24:7859–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Batlle E, Henderson JT, Beghtel H, van den Born MM, Sancho E, Huls G, et al. β-Catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the Iintestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of EphB/EphrinB. Cell. 2002;111:251–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kinch MS, Carles-Kinch K. Overexpression and functional alterations of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase in cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:59–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1022546620495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelinski DP, Zantek ND, Stewart JC, Irizarry AR, Kinch MS. EphA2 overexpression causes tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wykosky J, Gibo DM, Stanton C, Debinski W. EphA2 as a novel molecular marker and target in glioblastoma multiforme. Mol Cancer Res. 2005;3:541–51. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-05-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsouko E, Wang J, Frigo DE, Aydoğdu E, Williams C. miR-200a inhibits migration of triple-negative breast cancer cells through direct repression of the EPHA2 oncogene. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:1051–60. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kikuchi S, Kaibe N, Morimoto K, Fukui H, Niwa H, Maeyama Y, et al. Overexpression of Ephrin A2 receptors in cancer stromal cells is a prognostic factor for the relapse of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:485–94. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0390-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo DL, Zhang J, Yuen ST, Tsui WY, Chan AS, Ho C, et al. Reduced expression of EphB2 that parallels invasion and metastasis in colorectal tumours. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:454–64. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunne PD, Dasgupta S, Blayney JK, McArt DG, Redmond KL, Weir JA, et al. EphA2 expression is a key driver of migration and invasion and a poor prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;22:230–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Binda E, Visioli A, Giani F, Lamorte G, Copetti M, Pitter KL, et al. The EphA2 receptor drives self-renewal and tumorigenicity in stem-like tumor-propagating cells from human glioblastomas. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:765–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gozdecka M, Breitwieser W. The roles of ATF2 (activating transcription factor 2) in tumorigenesis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012;40:230–4. doi: 10.1042/BST20110630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paraiso KH, Das Thakur M, Fang B, Koomen JM, Fedorenko IV, John J, et al. Ligand-independent EPHA2 signaling drives the adoption of a targeted therapy-mediated metastatic melanoma phenotype. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:264–73. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coulthard MG, Morgan M, Woodruff TM, Arumugam TV, Taylor SM, Carpenter TC, et al. Eph/Ephrin signaling in injury and inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1493–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun T, Aceto N, Meerbrey KL, Kessler JD, Zhou C, Migliaccio I, et al. Activation of multiple proto-oncogenic tyrosine kinases in breast cancer via loss of the PTPN12 phosphatase. Cell. 2011;144:703–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danielsen SA, Eide PW, Nesbakken A, Guren T, Leithe E, Lothe RA. Portrait of the PI3K/AKT pathway in colorectal cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855:104–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carracedo A, Pandolfi PP. The PTEN-PI3K pathway: of feedbacks and cross-talks. Oncogene. 2008;27:5527–41. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu N, Zhao X, Liu M, Liu H, Yao W, Zhang Y, et al. Role of microRNA-26b in glioma development and its mediated regulation on EphA2. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aydoğdu E, Katchy A, Tsouko E, Lin CY, Haldosén LA, Helguero L, et al. MicroRNA-regulated gene networks during mammary cell differentiation are associated with breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:1502–11. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brand TM, Iida M, Wheeler DL. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;11:777–92. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.9.15050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miao B, Ji Z, Tan L, Taylor M, Zhang J, Choi HG, et al. EPHA2 is a mediator of vemurafenib resistance and a novel therapeutic target in melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:274–87. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhuang G, Brantley-Sieders DM, Vaught D, Yu J, Xie L, Wells S, et al. Elevation of receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 mediates resistance to trastuzumab therapy. Cancer Res. 2010;70:299–308. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Cutsem E, Köhne CH, Hitre E, Zaluski J, Chang Chien CR, Makhson A, et al. Cetuximab and chemotherapy as initial treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1408–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.