Abstract

This study compares the prevalence of tinnitus among patients who underwent medial temporal lobe resection, matched controls, and individuals with self-reported epilepsy to determine whether medial temporal lobe removal is associated with tinnitus.

Tinnitus is a phantom auditory percept in the absence of external acoustic stimulation. Its prevalence in the United States increases with age from 5% for young adults to 14% after age 65 years. Typically, tinnitus is viewed as having an exclusively auditory origin. However, recent brain imaging studies suggest that nonauditory brain structures could be involved in the genesis of tinnitus. In this respect, Rauschecker et al proposed that tinnitus might be the result of a dysfunctional neural “noise-cancellation” mechanism. They postulated that a peripheral deafferentation (eg, aging) generates a tinnitus-related activity that is normally blocked at the level of the medial geniculate nucleus via amygdalar inhibitory projections. However, no clinical evidence has supported this hypothesis to date. To clarify the role of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) structures (eg, amygdala and hippocampus) in tinnitus, we compared the prevalence of tinnitus among patients who underwent unilateral MTL resection encroaching on the amygdala with that among matched controls and participants with self-reported epilepsy (SRE) but no surgery. The surgical cases were expected to have increased difficulty in inhibiting the tinnitus signal and therefore a higher prevalence of tinnitus.

Methods

This study received approval from the institutional review board of the Ile-de-France VI Ethics Committee. The committee stated that no written or oral informed consent was required from patients.

Cases

Using medical records from July 15, 1991, through October 31, 2014, we mailed a letter announcing our survey to 247 consecutive surgical patients who had undergone unilateral MTL resection encroaching on the amygdala for the relief of medically intractable epilepsy. Among the 213 patients with a valid address, 166 (77.9%) responded to our health questionnaire.

Referent Controls

Using a simple random sampling method without replacement, we matched the 166 surgical patients by age and sex to 332 controls (2:1 ratio) and 332 participants with SRE, all of whom were recruited from the NutriNet-Santé Study cohort (N = 93 756). We used a multivariate logistic regression to investigate the risk of tinnitus across surgical cases and controls.

Results

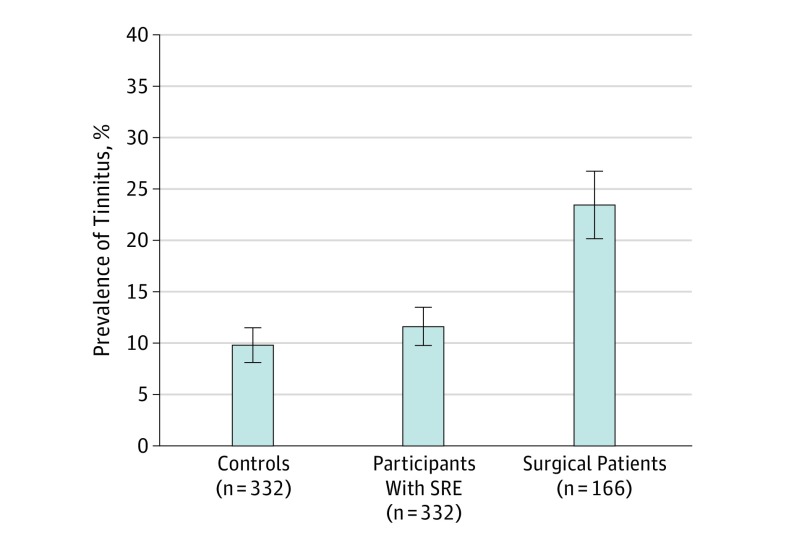

Consistent with previous reports, the prevalence of tinnitus was found to increase with age in all groups. The prevalence among the surgical patients (39 [23.5%]) was significantly higher than among the matched controls (33 [9.9%]) and participants with SRE (39 [11.7%]; P < .001; Figure). A sensitivity analysis, assuming that patients who did not return their questionnaires had no tinnitus, did not affect the result. However, the prevalence of self-reported hearing loss was not significantly different between groups (surgical patients, 9 [5.4%]; participants with SRE, 24 [7.2%]; and controls, 24 [7.2%]). The Table shows the clinical characteristics of the surgical patients, both with and without tinnitus.

Figure. Prevalence of Tinnitus Among Controls, Participants With Self-reported Epilepsy (SRE), and Patients With Epilepsy Who Underwent Surgery.

Error bars indicate SEs.

Table. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Surgical Epilepsy Cases, With or Without Tinnitus.

| Characteristic | Patients With Epilepsy Who Underwent Surgery, No. (%) | Sample Comparison, P Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 166) |

With Tinnitus (n = 39) |

Without Tinnitus (n = 127) |

||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 47.9 (10.8) | 52.0 (9.7) | 46.7 (10.8) | .006 |

| Male sex | 63 (38.0) | 14 (35.9) | 49 (38.6) | .76 |

| Side of surgery (left) | 83 (50.0) | 20 (51.3) | 63 (49.6) | .86 |

| Postsurgical delay, mean (SD), y | 11.3 (6.0) | 11.5 (5.4) | 11.2 (6.2) | .84 |

| Postsurgical seizure free (yes) | 143 (86.1) | 30 (76.9) | 113 (89.0) | .06 |

| Antiepileptic drug (yes) | 119 (71.7) | 33 (84.6) | 86 (67.7) | .04 |

| Hearing loss (yes) | 9 (5.4) | 6 (15.4) | 3 (2.4) | .47 |

| Hypersensitivity to noises or voices (yes) | 36 (21.7) | 13 (33.3) | 23 (18.1) | <.05 |

| Insomnia (yes) | 54 (32.5) | 22 (56.4) | 32 (25.2) | <.001 |

The χ2 test was used to compare qualitative variables, whereas the unpaired, 2-tailed t test was used to compare quantitative variables.

Discussion

The present study showed that the prevalence of tinnitus in MTL removal cases was more than 2 times the rate observed in matched controls and participants with SRE, suggesting an association between MTL removal and tinnitus. One possible hypothesis is that the MTL resection encroaching on the amygdala disrupts a noise-cancellation system in the central nervous system, which then increases the likelihood of tinnitus.

The surgical patients with tinnitus were older and reported a higher incidence of insomnia and hypersensitivity to noise compared with the patients without tinnitus. They were also more likely to be taking antiepileptic medications, indicating that they were at greater risk of continued seizures. Altogether, these data point to a specific group of patients with medically intractable epilepsy who present a particular susceptibility to developing tinnitus after MTL surgery. Additional studies, however, are necessary (1) to better understand the pathophysiological factors underlying the occurrence of tinnitus in nearly 1 in 4 patients with unilateral MLT resection and (2) to determine whether the surgical approach by itself, along with the MTL resection, contributed to the higher risk of tinnitus. The results of the present study provide evidence that the surgical resection of the MTL for the relief of intractable epilepsy is associated with an increased risk of tinnitus.

References

- 1.Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990;8(4):221-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC, Farwell WR. Prevalence and characteristics of tinnitus among US adults. Am J Med. 2010;123(8):711-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landgrebe M, Langguth B, Rosengarth K, et al. Structural brain changes in tinnitus: grey matter decrease in auditory and non-auditory brain areas. Neuroimage. 2009;46(1):213-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leaver AM, Turesky TK, Seydell-Greenwald A, Morgan S, Kim HJ, Rauschecker JP. Intrinsic network activity in tinnitus investigated using functional MRI. Hum Brain Mapp. 2016;37(8):2717-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rauschecker JP, Leaver AM, Mühlau M. Tuning out the noise: limbic-auditory interactions in tinnitus. Neuron. 2010;66(6):819-826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hercberg S, Castetbon K, Czernichow S, et al. The Nutrinet-Santé Study: a web-based prospective study on the relationship between nutrition and health and determinants of dietary patterns and nutritional status. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]