Key Points

Question

Does low-dose intravenous alteplase offer benefits over standard-dose intravenous alteplase in older, Asian, or severely affected patients with acute ischemic stroke?

Finding

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial that involved 3310 patients with acute ischemic stroke found no clear differential benefits of low-dose alteplase compared with standard-dose alteplase in disability outcomes, irrespective of age, race/ethnicity, and neurological severity. Increasing age and neurological severity, but not ethnicity, are associated with greater risk of death or disability following acute ischemic stroke in treated, thrombolysis-eligible patients.

Meaning

Decisions about using a lower dose of alteplase for thrombolysis-eligible patients with acute ischemic stroke should not be based solely on age, ethnicity, or neurological severity.

Abstract

Importance

A lower dose of intravenous alteplase appears to be a safer treatment option than the standard dose, reducing the risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage. There is uncertainty, however, over how this effect translates into an overall clinical benefit for patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS).

Objective

To assess whether older, Asian, or severely affected patients with AIS who are considered at high risk of bleeding after thrombolysis may benefit more from low-dose rather than standard-dose alteplase treatment.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study is a prespecified secondary analysis of the Enhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis Stroke Study (ENCHANTED), an international, randomized, open-label, blinded, end-point clinical trial of low-dose vs standard-dose intravenous alteplase for patients with AIS. From March 1, 2012, to August 31, 2015, a total of 3310 patients who had a clinical diagnosis of AIS as confirmed by brain imaging and who fulfilled the local criteria for thrombolysis treatment were included in the alteplase-dose arms. Patients were randomly assigned to receive low-dose (0.6 mg/kg; 15% as bolus and 85% as infusion over 1 hour) or standard-dose (0.9 mg/kg; 10% as bolus and 90% as infusion over 1 hour) alteplase. Of the 3310 randomized patients, 13 patients were excluded for missing consent, mistaken randomization, and duplicate randomization numbers. This secondary analysis was conducted between May 1, 2016, and April 28, 2017.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was a poor outcome defined by the combination of death and any disability as scored by the modified Rankin Scale (scores range from 2 to 6, with the highest score indicating death) at 90 days.

Results

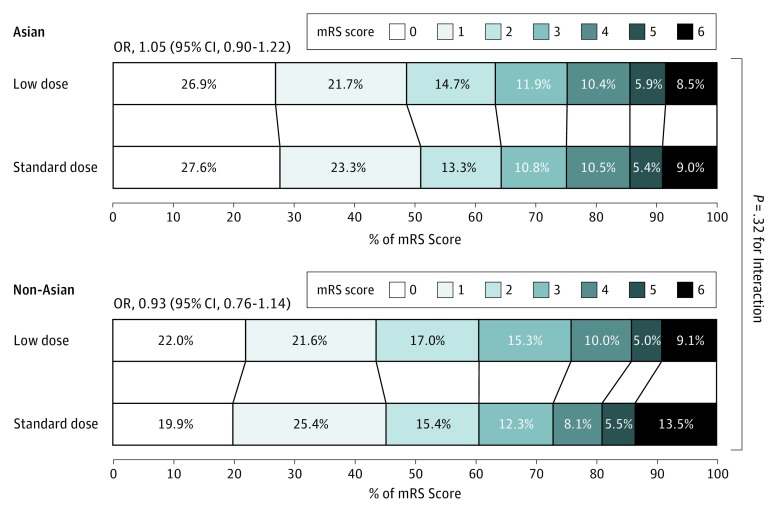

Of the 3297 patients included in the analysis, 1248 (37.9%) were women, and the mean (SD) age was 67 (13) years. No significant differences in the treatment effects were observed between low- and standard-dose alteplase for poor outcomes (death or disability) by age, ethnicity, or severity (all P > .37 for interaction). Similarly, the treatment effects of low- vs standard-dose alteplase on function outcome (ordinal shift of the modified Rankin Scale) in Asians (odds ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.90-1.22) was consistent with non-Asians (odds ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.76-1.14) (P = .32 for interaction). There were generally consistent reductions in rates of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage with low-dose alteplase, although this reduction was not statistically significant by age, ethnicity, or severity.

Conclusions and Relevance

This analysis found that the effects of low-dose alteplase were not clearly superior to the effects of standard-dose alteplase on death or disability in key demographic subgroups of patients with AIS. Further investigation is required to identify patients with AIS who may benefit from low-dose alteplase.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01422616

This secondary analysis reports on the association of low-dose and standard-dose intravenous alteplase treatment with age, ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian), and severity of acute ischemic stroke among patients in the ENCHANTED randomized clinical trial.

Introduction

Low-dose intravenous alteplase was approved in Japan for the treatment of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) within 3 hours of onset. This approval was based on a single-arm study, the Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial, showing that clinical efficacy and safety of low-dose alteplase in a Japanese population (0.6 mg/kg body weight; maximum 60 mg) were comparable to the efficacy and safety of standard-dose alteplase in other populations (0.9 mg/kg body weight; maximum 90 mg).1,2 This standard dose, which is approved by most regulatory authorities outside of Japan, has not been comprehensively tested in other Asian countries, but clinicians in the region may prefer low-dose alteplase because of its lower cost or apparent ability to reduce the risk of bleeding.3,4 Thus, uncertainties remain about the optimal dose of alteplase in Asian populations because observational studies have produced conflicting findings5,6,7,8 and randomized evidence has been absent.

Individual patient data from recent randomized clinical trials or information from stroke registries about the hazards and benefits of intravenous alteplase for different patient subgroups9,10,11,12 show similar proportional benefits of thrombolysis for patients 80 years of age or older and for those with a severe neurological deficit (with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score >25; NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with the highest score indicating greater neurological impairment). These data are reflected in the latest guideline recommendations of the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association,13 as well as the Royal College of Physicians.14 There are proven clinical benefits from thrombolysis for older patients and those with severe AIS, but these features increase the risk of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH).13 Accordingly, low-dose alteplase may maintain the benefits of treatment while reducing the risk of sICH.

In the recently completed alteplase-dose evaluation arm of the quasifactorial Enhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis Stroke Study (ENCHANTED), use of low-dose alteplase compared with standard-dose alteplase for thrombolysis-eligible AIS patients was not shown to meet the predefined noninferiority margin of the conventional binary clinical end point of death and disability, defined by scores of 2 to 6 on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at 90 days (the mRS scores range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms and 6 indicating death). However, the ENCHANTED trial did show that low-dose alteplase was noninferior for overall functional recovery through ordinal analysis of the mRS and resulted in significantly less severe sICH than did standard-dose alteplase.4,15,16 Therefore, it is plausible that low-dose alteplase may be a preferable treatment for certain types of patients. In this prespecified secondary analysis, we used data from the ENCHANTED trial to provide detailed information about the treatment effects of low-dose vs standard-dose intravenous alteplase and their association with age, ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian), and severity of AIS.

Methods

Participants

The ENCHANTED trial was an international, multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded, end-point clinical trial, the details of which are outlined elsewhere.4,15,16 In brief, from March 1, 2012, through August 31, 2015, a total of 3310 patients who received a clinical diagnosis of AIS that was confirmed by brain imaging and who fulfilled the local criteria for thrombolysis treatment were included in the alteplase-dose arm, with a random assignment to receive low-dose (0.6 mg/kg; 15% as bolus and 85% as infusion over 1 hour) or standard-dose (0.9 mg/kg; 10% as bolus and 90% as infusion over 1 hour) intravenous alteplase. The study protocol for the ENCHANTED trial was approved by the appropriate ethics committee at each participating center, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient or an appropriate surrogate. This secondary analysis was conducted between May 1, 2016, and April 28, 2017.

Procedures

Key demographic and clinical characteristics were recorded at the time of enrollment. Stroke severity was measured using the NIHSS at baseline, 24 hours, and day 7 (or earlier on discharge from hospital). Uncompressed digital images from all baseline and follow-up computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and angiography were collected in DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) format on a CD-ROM, identified only with the patient’s unique study number, and uploaded by a special-purpose–built, web-based system for central analysis at the George Institute for Global Health. All brain scans that revealed an intracranial hemorrhage were reviewed by at least 2 independent assessors (who were not part of this study) who were blind to the clinical data, treatment, and date and sequence of the scan using MIStar, version 3.2 (Apollo Medical Imaging Technology). Assessors graded any hemorrhage as intracerebral, subarachnoid, intraventricular, subdural, or other; sICH was graded across all standard definitions (eAppendix in the Supplement).

The primary efficacy outcome in these analyses was a composite end point of death or any disability at 90 days, defined by scores of 2 to 6 on the mRS. Secondary efficacy outcomes included scores of 3 to 6 on the mRS, death alone (mRS score of 6), and an ordinal analysis of the full range of scores on the mRS. The safety outcome was sICH, defined according to standard criteria.

Statistical Analysis

The treatment effects of low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase on the disability outcomes and sICH were determined using logistic regression models, and the heterogeneity of the differential effect according to alteplase dose across subgroups was estimated by adding an interaction term to the statistical models. Proportional odds regression models were used to determine the treatment effects on the ordinal mRS across subgroups of patients defined by age, ethnicity, and neurological severity; the proportional odds assumption was fulfilled in all models.17,18 Sensitivity analyses were performed using age and baseline NIHSS score as continuous variables in logistic regression models with the adjustment for variables described in the following paragraph.

The association of age (<50, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, and ≥80 years), ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian), and neurological severity (baseline NIHSS scores of 0-4, 5-10, 11-15, 16-21, and ≥22) with death or disability, death, and sICH were estimated using logistic regression models, with adjustment for the baseline covariates (time from onset to randomization [<3 hours vs ≥3 hours]; age; sex; ethnicity; baseline systolic blood pressure; baseline NIHSS score; any history of stroke; coronary artery disease; diabetes mellitus; atrial fibrillation; hypercholesterolemia; premorbid mRS score [0 or 1]; previous use of warfarin sodium anticoagulant, aspirin, or other antiplatelet agent; and randomized treatment [low dose vs standard dose]) as well as for management over the first 7 days (systolic blood pressure at 24 hours; fever occurrence; provision of nasogastric tube feeding; mobilization of a patient by a therapist; use of compression stockings, intravenous steroids, and neurosurgery; any admission to a stroke unit or intensive care unit; and any rehabilitation or decision to withdraw active care). The heterogeneity of the associations across subgroups was also estimated by adding an interaction term to the model. Data were reported as odds ratios and 95% CIs. Two-sided P values were reported, with P < .05 considered statistically significant. SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc), was used for analyses.15

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Management Details

From March 1, 2012, through August 31, 2015, a total of 3310 patients were randomized; 1654 were assigned to low-dose alteplase and 1643 to standard-dose alteplase after 13 patients were excluded (9 did not provide informed consent, 1 was mistakenly randomized, and 3 had duplicate randomization numbers).16 The remaining 3297 patients (1248 [37.9%] were women, and the mean [SD] age was 67 [13] years) were included in the age analyses. The Table shows the baseline characteristics of patients by age groups: older patients were significantly more likely to be women, to be of non-Asian ethnicity, to be hypertensive, and to have a history of comorbidities and concomitant prior use of aspirin and statin therapy. In addition, they were more likely to have had strokes of greater neurological severity.

Table. Baseline Characteristics by Age Groupa.

| Characteristic | Age Group, y | P Valueb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 | ≥80 | ||

| Time from stroke onset to randomization, h | 2.7 (2.1-3.6) | 2.8 (2.1-3.5) | 2.8 (2.1-3.5) | 2.7 (1.9-3.4) | 2.5 (1.9-3.2) | <.001 |

| Female sex | 115/352 (32.7) | 196/626 (31.3) | 289/897 (32.2) | 397/950 (41.8) | 251/472 (53.2) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Asian | 98/352 (27.8) | 163/624 (26.1) | 273/895 (30.5) | 334/948 (35.2) | 344/472 (72.9) | <.001 |

| Asian | 254/352 (72.2) | 461/624 (73.9) | 622/895 (69.5) | 614/948 (64.8) | 128/472 (27.1) | |

| Clinical features | ||||||

| Systolic BP, mm Hg | 143.1 (21.6) | 147.4 (20.2) | 150.3 (19.4) | 150.1 (18.8) | 152.8 (19.4) | <.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mm Hg | 88.0 (13.5) | 88.1 (12.2) | 85.3 (12.1) | 82.5 (12.8) | 80.7 (13.4) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, beats per min | 80.7 (12.9) | 79.8 (14.5) | 78.3 (14.5) | 78.5 (16.8) | 79.3 (16.7) | .07 |

| NIHSS scorec | 8 (5-12) | 7 (5-12) | 8 (5-13) | 9 (6-15) | 10 (6-16) | <.001 |

| NIHSS score ≥14 | 75/352 (21.3) | 115/626 (18.4) | 198/897 (22.1) | 304/950 (32.0) | 161/472 (34.1) | <.001 |

| GCS scored | 15 (14-15) | 15 (14-15) | 15 (14-15) | 15 (13-15) | 15 (13-15) | <.001 |

| Severe GCS score (3-8) | 13/352 (3.7) | 18/626 (2.9) | 37/897 (4.1) | 49/950 (5.2) | 19/472 (4.0) | .27 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Hypertension | 143/352 (40.6) | 342/622 (55.0) | 591/895 (66.0) | 661/947 (69.8) | 328/472 (69.5) | <.001 |

| Previous stroke | 36/352 (10.2) | 95/626 (15.2) | 166/897 (18.5) | 203/950 (21.4) | 89/472 (18.9) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 16/352 (4.6) | 47/622 (7.6) | 135/895 (15.1) | 182/947 (19.2) | 99/472 (21.0) | <.001 |

| Other heart disease (valvular or other) | 19/352 (5.4) | 31/622 (5.0) | 61/895 (6.8) | 69/947 (7.3) | 55/472 (11.7) | .004 |

| Atrial fibrillation confirmed on ECG | 23/352 (6.5) | 60/622 (9.7) | 136/894 (15.2) | 253/946 (26.7) | 164/471 (34.8) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 40/352 (11.4) | 106/622 (17.0) | 192/895 (21.5) | 222/947 (23.4) | 86/472 (18.2) | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 28/352 (8.0) | 73/622 (11.7) | 140/895 (15.6) | 192/947 (20.3) | 122/472 (25.9) | <.001 |

| Current smoker | 119/352 (33.8) | 205/621 (33.0) | 252/895 (28.2) | 163/945 (17.3) | 31/471 (6.6) | <.001 |

| Prestroke function (mRS)e | ||||||

| No symptoms | 328/352 (93.2) | 554/622 (89.1) | 744/894 (83.2) | 759/946 (80.2) | 289/472 (61.2) | <.001 |

| Symptoms without disability | 24/352 (6.8) | 68/622 (10.9) | 150/894 (16.8) | 187/946 (19.8) | 183/472 (38.8) | |

| Medication at time of admission | ||||||

| Antihypertensive agent(s) | 71/352 (20.2) | 208/622 (33.4) | 411/895 (45.9) | 516/947 (54.5) | 292/472 (61.9) | <.001 |

| Warfarin anticoagulation | 14/352 (4.0) | 18/621 (2.9) | 16/895 (1.8) | 23/945 (2.4) | 11/472 (2.3) | .24 |

| Aspirin or other antiplatelet agent | 34/352 (9.7) | 76/621 (12.2) | 204/895 (22.8) | 274/945 (29.0) | 164/472 (34.8) | <.001 |

| Statin or other lipid-lowering agent | 33/352 (9.4) | 73/621 (11.8) | 155/895 (17.3) | 223/944 (23.6) | 131/472 (27.8) | <.001 |

| Brain imaging features | ||||||

| Visible early ischemic changes | 72/352 (20.5) | 123/622 (19.8) | 206/895 (23.0) | 248/947 (26.2) | 122/472 (25.9) | .002 |

| CT or MRI scan showing proximal occlusion | 45/350 (12.9) | 88/618 (14.2) | 129/886 (14.6) | 171/936 (18.3) | 72/456 (15.8) | .07 |

| Final diagnosis at time of hospital separation | ||||||

| Nonstroke diagnosis | 26/344 (7.6) | 22/610 (3.6) | 29/880 (3.3) | 10/933 (1.1) | 10/467 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Large artery occlusion due to significant atheroma | 129/344 (37.5) | 278/610 (45.6) | 367/880 (41.7) | 367/933 (39.3) | 129/467 (27.6) | |

| Small vessel or perforating vessel lacunar disease | 89/344 (25.9) | 144/610 (23.6) | 203/880 (23.1) | 163/933 (17.5) | 74/467 (15.9) | |

| Cardioemboli | 43/344 (12.5) | 66/610 (10.8) | 136/880 (15.5) | 240/933 (25.7) | 156/467 (33.4) | |

| Dissection | 9/344 (2.6) | 9/610 (1.5) | 4/880 (0.5) | 2/933 (0.2) | 1/467 (0.2) | |

| Other or uncertain origin | 48/344 (14.0) | 91/610 (14.9) | 141/880 (16.0) | 151/933 (16.2) | 97/467 (20.8) | |

| Time from stroke onset to treatment, min | 175 (135-225) | 176 (133-225) | 175 (135-220) | 170 (122-215) | 153 (116-195) | <.001 |

| Treatment allocation to low-dose alteplase | 179/352 (50.9) | 312/626 (49.8) | 441/897 (49.2) | 478/950 (50.3) | 244/472 (51.7) | .92 |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CT, computed tomographic; ECG, electrocardiogram; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale, MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

Data are number/total number (percentage) of patients, mean (SD) value, or median value (interquartile range).

Based on χ2, analysis of variance, or the Kruskal-Wallis test.

The NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with the highest score indicating greater neurological impairment.

The GCS scores range from 3 to 15, with the lower score indicating deeper loss of consciousness.

The mRS scores range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death.

There were 3291 patients (2079 self-identified as Asian and 1212 as non-Asian) with available information for ethnicity analyses. eTable 1 in the Supplement indicates that patients of non-Asian ethnicity were significantly older; were more likely to be women; had greater comorbidities (eg, hypertension and atrial fibrillation); had more concomitant use of antihypertensive, warfarin, aspirin, and/or statin therapy; and were treated more quickly with alteplase than were patients of Asian ethnicity (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

There were 3297 patients (median [interquartile range] baseline NIHSS score of 8 [5-14]) included in the severity analysis. Patients who presented with more severe neurological impairment had characteristics similar to older patients except they were more likely to be of Asian ethnicity (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Differences in the use of alteplase and other management factors over the first 7 days after randomization by age, ethnicity, and stroke severity subgroups are reported in eTables 2, 4, and 5, respectively, in the Supplement.

Association of Low-Dose vs Standard-Dose Alteplase With Age, Ethnicity, and Severity

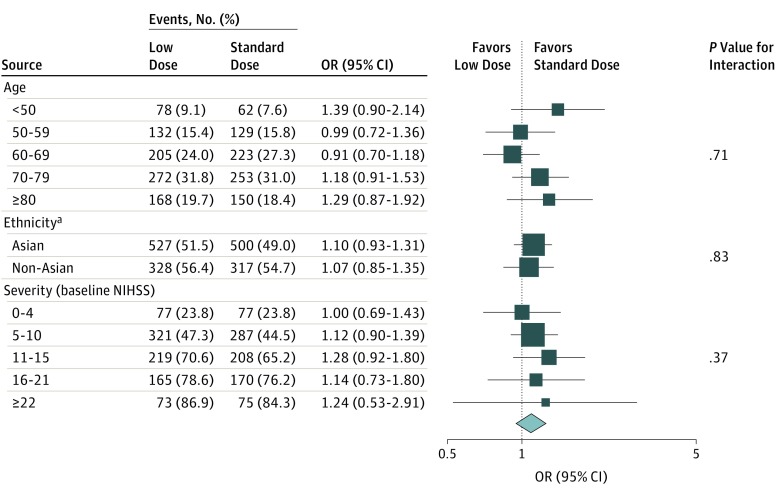

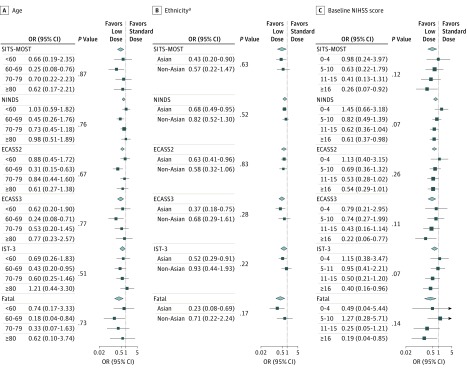

No clear differential effect of alteplase was observed in any particular age group for the disability outcome, whether defined by different cut points (2 to 6 or 3 to 6) or on an ordinal analysis of the full range of scores on the mRS (all P ≥ .51 for interaction; Figure 1; eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement). Similarly, there was consistency of the lower risk of sICH for low-dose alteplase across age groups (all P > .50 for interaction; Figure 2A; eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Randomized Treatment Effects on Death or Disability at 90 Days by Age, Ethnicity, and Stroke Severity.

Solid boxes represent estimates of treatment effect; horizontal lines, 95% CI; and diamond, the estimate and 95% CI for the overall effect. Areas of the boxes are proportional to the number of outcomes. NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; OR, odds ratio.

aData from Figure 2 in Anderson et al.16

Figure 2. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage by Age, Ethnicity, and Stroke Severity.

Treatment effects on symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage are presented by age (A), ethnicity (B), and stroke severity (C). Solid boxes represent estimates of treatment effect; horizontal lines, 95% CI; and diamond, the estimate and 95% CI for the overall effect. Areas of the boxes are proportional to the number of outcomes. ECASS indicates European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study; IST, International Stroke Trial; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; NINDS, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke; OR, odds ratio; and SITS-MOST, Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke Monitoring Study.

aData from Figure S8 of the Supplementary Appendix in Anderson et al.16

In a comparison of Asian and non-Asian patients, there was no significant difference in the disability outcomes between the 2 doses of alteplase, whether defined by death or disability (all P ≥ .32 for interaction, Figure 1; eTable 9 in the Supplement) or an ordinal analysis of the mRS for low-dose (odds ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.90-1.22) vs standard-dose (odds ratio, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.76-1.14) alteplase (P = .32 for interaction) (Figure 3). Similarly, regarding the primary outcome, no clear beneficial effect of 1 dose over the other was found across patients from different regions of the world (China; United Kingdom, continental Europe, or Australia; Asia, other than China; and South America [eFigure 1 in the Supplement]). Furthermore, there was no heterogeneity in the differential effect of alteplase dose on the risk of sICH between Asian patients and non-Asian patients (Figure 2B; eTable 10 in the Supplement).16

Figure 3. Randomized Treatment Effects on Functional Outcome According to the Modified Rankin Scale at 90 Days, by Ethnicity.

Scores on the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death. OR indicates odds ratio.

The treatment effects of low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase on various disability outcomes (mRS scores of 2-6, 3-6, or 6 [death] or ordinal analysis) remained consistent across the grades of baseline neurological severity (Figure 1; eTables 11 and 12 in the Supplement), even after accounting for treatment delay (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). The differential treatment effect on the risk of sICH was consistent with increasing severity (Figure 2C; eTable 13 in the Supplement).

Prognostic Significance of Age, Ethnicity, and Neurological Severity

Older patients were more likely to have poor outcome (mRS scores of 2-6, 3-6, or 6 [death]; all P < .01 for trend; eTable 14 in the Supplement), but there was no clear association of sICH across a broad range of criteria with increasing age, irrespective of alteplase dose (eTable 15 in the Supplement). Similarly, no significant association was found between ethnicity and poor outcome (death or disability; eTable 16 in the Supplement) or sICH (eTable 17 in the Supplement). However, these end points were associated with increasing neurological severity of AIS (mRS scores of 2-6, 3-6, or 6 [death]; all P < .001 for trend; sICH, P < .001 for trend according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the third criterion of European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study), after adjustment for confounders and alteplase dose (eTables 18 and 19 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this prespecified secondary analysis of the ENCHANTED trial, no clear differences were found in the treatment effects of low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase on the main disability outcomes according to age, ethnicity, and baseline neurological severity of thrombolysis-eligible patients with AIS. Thus, for these key patient characteristics, we could not identify a clinically important subgroup who clearly benefitted more from low-dose than standard-dose alteplase. However, there was a statistically insignificant consistency in the finding that a lower risk of sICH was associated with low-dose alteplase across various age groups, between Asian patients and non-Asian patients, and with increasing levels of neurological severity.

To our knowledge, this secondary analysis provides the only randomized evidence comparing the effects of low-dose alteplase with those of standard-dose alteplase. Although the sICH rates were lower with low-dose alteplase, they could not be associated with increasing age and did not influence the differential treatment effect between the alteplase doses on the disability outcomes. Thus, age is not a sufficient criterion to determine which dose of alteplase to use; older patients with AIS should not be systematically denied use of standard-dose alteplase on the assumption that it is a more hazardous treatment for very old patients than for younger patients. Our randomized data partially contradict 3 observational studies that have suggested low-dose alteplase is associated with both a lower risk of sICH and a higher odds of independent recovery for elderly patients with AIS in Eastern Asia.5,19,20

Because we found no significant ethnic variation in the differential treatment effects of low-dose and standard-dose alteplase on the disability outcomes or sICH, ethnicity cannot be regarded as a modifying factor in the risks and benefits of low-dose or standard-dose alteplase. Systematic reviews21,22 of the current observational thrombolysis studies of patients with AIS in Asia are consistent with our analysis, finding trends toward better functional outcomes from standard-dose alteplase rather than low-dose alteplase despite differential risks of sICH. Despite the popular belief in and underlying rationale for the preferential use of low-dose alteplase among patients with AIS in Asia because of higher bleeding risks from lytic treatment, our analysis did not indicate any variation in the differential treatment effects of the 2 doses of alteplase between Asian patients and non-Asian patients. Thus, our findings do not support the current practice in many Asian countries of using low-dose alteplase because it is expected to be more efficacious than the standard dose.1,2,23

The ENCHANTED trial was uniquely placed to assess the effects of low-dose and standard-dose alteplase by stroke severity, as well as to determine whether low-dose alteplase modified the balance of benefits and risks. Our analysis indicates that the benefits of low-dose alteplase in reducing the severity of sICH was not significantly affected by stroke severity. Furthermore, the use of low-dose alteplase was not associated with a worse 90-day outcome, even for patients with a severe deficit. Although the benefits of standard-dose alteplase were independent of stroke severity, the rate of favorable outcome depended on neurological severity.9 For patients with an NIHSS score of 11 or higher, the absolute increases in good outcomes resulting from standard-dose alteplase vs placebo were estimated at 3.2% to 4.5%. Thus, low-dose alteplase did not appear to alter the odds of recovery for these types of patients.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this analysis include the use of a large sample size with a high proportion of older people from both non-Asian and Asian populations in a variety of health care settings worldwide, which enhances the generalizability of the ENCHANTED trial results. In addition, there were high rates of patient follow-up and adherence to treatment. The rigorous assessment of serious adverse events, especially sICH, ensured that any harms associated with the treatments were reliably detected and quantified. However, the analysis also had some limitations. Imprecision in the estimates of the treatment effect may have arisen from interobserver variability in mRS scoring.24 Furthermore, the inclusion of patients who had a generally mild neurological severity and were treated with a longer delay from symptom onset than patients in other trials and evaluations of alteplase for AIS9 may cause concern over the external validity of these results. Finally, presented here are subgroup analyses with reduced statistical power, which limited our ability to detect modest differences between the randomized groups.

Conclusions

This prespecified secondary analysis of the ENCHANTED trial has shown that the differential treatment effects of low-dose vs standard-dose alteplase on clinical outcomes were consistent across the subgroups defined by age, ethnicity, and AIS severity. There was no statistically significant consistency in the finding that low-dose alteplase was associated with a lower risk of sICH for patients of increasing age, with Asian or non-Asian ethnicity, and with increasing neurological severity. These results suggest that decisions about the dose of alteplase used in thrombolysis-eligible patients with AIS should not be based solely on age, ethnicity, or stroke severity.

eAppendix. Definitions of Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage

eReferences.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 2. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics by Stroke Severity

eTable 4. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Age Groups

eTable 5. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Stroke Severity

eTable 6. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 7. Randomized Treatment Effects on Modified Rankin Scale at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 8. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 9. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 10. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Ethnicity

eTable 11. Randomized Treatment Effects on Modified Rankin Scale at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 12. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 13. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Age

eTable 14. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 days by Age Groups

eTable 15. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 16. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 days by Ethnicity

eTable 17. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 18. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 19. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage by Stroke Severity

eFigure 1. Randomized Treatment Effects on Death or Disability at 90 days by Region

eFigure 2. Randomized Treatment Effects on Death or Disability/sICH by Stroke Severity and Time from Onset to Treatment

References

- 1.Yamaguchi T, Mori E, Minematsu K, et al. ; Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT) Group . Alteplase at 0.6 mg/kg for acute ischemic stroke within 3 hours of onset: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial (J-ACT). Stroke. 2006;37(7):1810-1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mori E, Minematsu K, Nakagawara J, Yamaguchi T, Sasaki M, Hirano T; Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II Group . Effects of 0.6 mg/kg intravenous alteplase on vascular and clinical outcomes in middle cerebral artery occlusion: Japan Alteplase Clinical Trial II (J-ACT II). Stroke. 2010;41(3):461-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueshima S, Matsuo O. The differences in thrombolytic effects of administrated recombinant t-PA between Japanese and Caucasians. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87(3):544-546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang Y, Sharma VK, Robinson T, et al. ; ENCHANTED Investigators . Rationale, design, and progress of the ENhanced Control of Hypertension ANd Thrombolysis strokE stuDy (ENCHANTED) trial: an international multicenter 2 × 2 quasi-factorial randomized controlled trial of low- vs. standard-dose rt-PA and early intensive vs. guideline-recommended blood pressure lowering in patients with acute ischaemic stroke eligible for thrombolysis treatment. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(5):778-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao AC, Liu CK, Chen CH, et al. ; Taiwan Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke (TTT-AIS) Study Group . Different doses of recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator for acute stroke in Chinese patients. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2359-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim BJ, Han MK, Park TH, et al. Low- versus standard-dose alteplase for ischemic strokes within 4.5 hours: a comparative effectiveness and safety study. Stroke. 2015;46(9):2541-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao X, Wang Y, Pan Y, et al. ; Thrombolysis Implementation and Monitor of Acute Ischemic Stroke in China Investigators . Standard-dose intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator for stroke is better than low doses. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2354-2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rha JH, Shrivastava VP, Wang Y, et al. ; SITS Investigators . Thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke with alteplase in an Asian population: results of the multicenter, multinational Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Non-European Union World (SITS-NEW). Int J Stroke. 2014;9(suppl A100):93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emberson J, Lees KR, Lyden P, et al. ; Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists’ Collaborative Group . Effect of treatment delay, age, and stroke severity on the effects of intravenous thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;384(9958):1929-1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiteley WN, Emberson J, Lees KR, et al. ; Stroke Thrombolysis Trialists’ Collaboration . Risk of intracerebral haemorrhage with alteplase after acute ischaemic stroke: a secondary analysis of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(9):925-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazya MV, Lees KR, Collas D, et al. IV thrombolysis in very severe and severe ischemic stroke: results from the SITS-ISTR Registry. Neurology. 2015;85(24):2098-2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford GA, Ahmed N, Azevedo E, et al. Intravenous alteplase for stroke in those older than 80 years old. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2568-2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention . Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(2):581-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royal College of Physicians Stroke guidelines. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/stroke-guidelines. Published October 3, 2016. Accessed November 24, 2016.

- 15.Anderson CS, Woodward M, Arima H, et al. ; ENCHANTED Investigators . Statistical analysis plan for evaluating low- vs. standard-dose alteplase in the ENhanced Control of Hypertension and Thrombolysis Stroke Study (ENCHANTED). Int J Stroke. 2015;10(8):1313-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson CS, Robinson T, Lindley RI, et al. ; ENCHANTED Investigators and Coordinators . Low-dose versus standard-dose intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(24):2313-2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodward M. Epidemiology Study Design and Data Analysis. 3rd ed Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bath PM, Lees KR, Schellinger PD, et al. ; European Stroke Organisation Outcomes Working Group . Statistical analysis of the primary outcome in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 2012;43(4):1171-1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao AC, Hsu HY, Chung CP, et al. ; Taiwan Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke (TTT-AIS) Study Group . Outcomes of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke in Chinese patients: the Taiwan Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Ischemic Stroke (TTT-AIS) study. Stroke. 2010;41(5):885-890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takayanagi S, Ochi T, Hanakita S, Suzuki Y, Maeda K. The safety and effectiveness of low-dose recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (0.6 mg/kg) therapy for elderly acute ischemic stroke patients (≥80 years old) in the pre-endovascular era. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2014;54(6):435-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma VK, Ng KW, Venketasubramanian N, et al. Current status of intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in Asia. Int J Stroke. 2011;6(6):523-530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu MD, Ning WD, Wang RC, et al. Low-dose versus standard-dose tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke in Asian populations: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(52):e2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta RH, Cox M, Smith EE, et al. ; Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Program . Race/ethnic differences in the risk of hemorrhagic complications among patients with ischemic stroke receiving thrombolytic therapy. Stroke. 2014;45(8):2263-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, Lees KR. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic review. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3393-3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Definitions of Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage

eReferences.

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 2. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 3. Baseline Characteristics by Stroke Severity

eTable 4. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Age Groups

eTable 5. Use of Alteplase and Other Management Details During the First 7 Days of Hospital Admission by Stroke Severity

eTable 6. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 7. Randomized Treatment Effects on Modified Rankin Scale at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 8. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Age Groups

eTable 9. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 10. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Ethnicity

eTable 11. Randomized Treatment Effects on Modified Rankin Scale at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 12. Randomized Treatment Effects on Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 13. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Age

eTable 14. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 days by Age Groups

eTable 15. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Ethnicity (Asian vs non-Asian)

eTable 16. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage Outcomes According to Standard Definitions at 90 days by Ethnicity

eTable 17. Randomized Treatment Effects on Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 18. Major Clinical Outcomes at 90 Days by Stroke Severity

eTable 19. Symptomatic Intracerebral Hemorrhage by Stroke Severity

eFigure 1. Randomized Treatment Effects on Death or Disability at 90 days by Region

eFigure 2. Randomized Treatment Effects on Death or Disability/sICH by Stroke Severity and Time from Onset to Treatment