Abstract

Unlike fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare, most Medicare Advantage (MA) plans have a preferred network of care providers that serve most of a plan’s enrollees. Little is known about how the quality of care MA enrollees receive differs from that of FFS Medicare enrollees. This article evaluates the differences in the quality of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) that Medicare Advantage and FFS beneficiaries entered in the period 2012–14. After we controlled for patients’ clinical, demographic, and residential neighborhood effects, we found that FFS Medicare patients have substantially higher probabilities of entering higher-quality SNFs (those rated four or five stars by Nursing Home Compare) and those with lower readmission rates, compared to MA enrollees. The difference between MA and FFS Medicare SNF selections was less for enrollees in higher-quality MA plans than those in lower-quality plans, but Medicare Advantage still guided patients to lower-quality facilities.

Each year Medicare beneficiaries can choose between two options for health coverage: traditional fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare or Medicare Advantage (MA). The latter is a form of managed care in which patients can choose to enroll in plans offered by private insurance companies. These plans are paid for on a capitated basis by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and have greater flexibility in their offerings than FFS Medicare. Over the past decade the share of beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Advantage has steadily increased, reaching 31 percent in 2016.1

While both Medicare Advantage and FFS Medicare cover the same services, most MA plans have a preferred network of care providers. The Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003 permitted this practice because narrow provider networks may reduce the costs of delivering care. Several studies have studied narrow hospital networks and found that insurers have the potential to cut costs by limiting patients’ choice of providers.2–7 At the same time, MA plans must balance level of payment to providers and the quality of care delivered to patients, since higher-quality providers might not be willing to accept low payment rates.8 However, we have little understanding of the quality of care provided in MA plan networks and plans’ selection of hospitals and physician providers. A Massachusetts study found that plans with narrow networks excluded hospitals with higher star ratings more frequently than did plans with broader networks4 and often excluded other prestigious but expensive research institutions.9 Qualitatively, both insurance companies and hospital executives have described controlling costs by limiting access to certain facilities as a key strategy, particularly with the introduction of the Affordable Care Act.10 The paucity of research is mostly due to the unavailability of claims data for MA beneficiaries.

This study aims to evaluate the differential quality of skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) selected by MA and FFS Medicare enrollees. A recent report by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission documented that FFS payment rates for SNF services were about 23 percent higher than MA payment rates.11 There is great variation in quality, payer mix, and cost factors across SNFs,12–16 and MA plans may therefore be contracting with lower-quality SNF providers. Because SNF patients often have more severe care needs than other Medicare beneficiaries, it is particularly important to understand how SNF characteristics are associated with network formation and MA beneficiaries’ choice of SNFs. Research has found that beneficiaries move from Medicare Advantage to FFS in higher numbers after a SNF stay. This raises the question of how the quality of SNF care received by MA beneficiaries may differ from that received by FFS patients.17 It is possible to study these issues using the mandatory patient assessments that each SNF submits to CMS on all entering beneficiaries, including MA patients.

We examined data for all elderly Medicare beneficiaries newly admitted to SNFs between 2012 and 2014 to assess the association of SNF quality ratings with selection decisions among FFS patients, compared to MA patients. Because we did not know specific contracting details for all MA plans, we assumed that any residual differences in the quality of SNFs chosen by MA and FFS beneficiaries, after other SNF characteristics were controlled for, were due to MA plans steering patients to preferred providers.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES

All data were for the period 2012–14. We drew enrollment and demographic information from the 100 percent Medicare Beneficiary Enrollment Summary File. We gathered information on beneficiaries’ SNF admission using a 100 percent Minimum Data Set (MDS) file (version 3). The MDS has been substantially validated as an accurate source of data on patients’ utilization; diagnoses; and physical, cognitive, and emotional functioning.18–21 We merged the MA enrollee data with Medicare’s Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) to identify each beneficiary’s MA plan, by plan contract with CMS. CMS requires all MA plans to report quality information for all of their covered beneficiaries in HEDIS. Then we merged our data set at the patient level with MDS claims data to create a data set of SNF admissions for both MA and FFS Medicare patients. We linked this data set to Medicare Advantage plan ratings by contract.22 These ratings range from one to five stars and are calculated monthly by CMS based on scores on thirty-two measures across five domains.23 We added several SNF-level characteristics from the Online Survey Certification and Reporting System (OSCAR), a data set assembled by CMS based on SNF inspection results that collected detailed information on SNF characteristics, and from its successor, the Certification and Survey Provider Enhanced Reports (CASPER). We also added facility rehospitalization rates and case-mix adjusters from publicly available SNF files from LTCfocus.24 Housed at Brown University, LTCfocus compiles nursing home information from OSCAR (CASPER), the MDS, Medicare claims, and the Area Health Resource File to create publicly available databases of nursing home characteristics over time.

STUDY COHORT

We included all Medicare enrollees ages sixty-five and older who were admitted to a SNF in 2012–14 and who had not been admitted to one in the previous year. We excluded prior-year admissions because those admissions may have an overriding effect on the patients’ SNF selection decisions in the relevant year.

OUTCOMES OF INTEREST

Our outcomes of interest were Nursing Home Compare quality ratings (ranging from one to five stars) and adjusted rates of rehospitalization.24–25 While the measures used in the SNF star ratings have come under scrutiny in recent years,26–30 they still provide a useful summary of SNF quality, and are also correlated with SNF costs.31 We chose to use publicly available star ratings from Nursing Home Compare because these are the scores that Medicare enrollees would have access to when making their SNF selection.

We obtained data on adjusted thirty-day rehospitalization rates for each SNF from LTCfocus.org. (CMS did not make Nursing Home Compare readmission rates public until 2016.) Research has found that using a SNF with historically lower rehospitalization rates reduces a patient’s likelihood of future rehospitalization.32 The adjusted rehospitalization rates are calculated as the observed rate of rehospitalization within thirty days at a given SNF divided by the expected number of rehospitalizations at that SNF, multiplied by a national average.32 The expected number of rehospitalizations is calculated by LTCfocus from a predictive model that includes thirty variables from the MDS to adjust for SNF characteristics and case-mix.24

EXPLANATORY VARIABLES

Our primary explanatory variable was MA or FFS enrollment status. A beneficiary was considered an MA enrollee if they were enrolled in an MA plan at the time of SNF admission. We stratified MA enrollment status by enrollees in higher-quality MA plans (four or more stars) and lower-quality MA plans (fewer than four stars).

To ensure comparability between FFS and MA enrollees, we included covariates for age, sex, race, residential ZIP code, and Medicaid eligibility in the month of SNF admission from the enrollment file. We also included indicators of marital status and primary language from the MDS. Clinical control variables included activities of daily living,33 cognitive function,34 and indicators of several diagnoses.

In our choice models we also included controls for SNF number of beds, shares of Medicare-paid, Medicare Advantage, and Medicaid-paid patients; whether the SNF belonged to a chain; and the SNF occupancy rate, ownership status (nonprofit or public versus for profit), and distance from the beneficiary’s residence. Previous work has found distance to be the principal factor influencing choice of SNFs.35 We calculated the distance from the centroid of a beneficiary’s ZIP code to the SNF’s latitude and longitude using the haversine formula.36

STATISTICAL METHODS

We used a three-step analytic approach. First, we examined any evidence of differential selection of SNFs based upon geography alone. Next, in our primary analysis, we examined adjusted differences in the quality of patients’ chosen SNFs between Medicare enrollee categories (those in FFS Medicare and those in higher- or lower-quality MA plans). Finally, we used a choice model to assess whether the relationship between SNF characteristics and enrollees’ choice of facilities varied across the three enrollee categories.

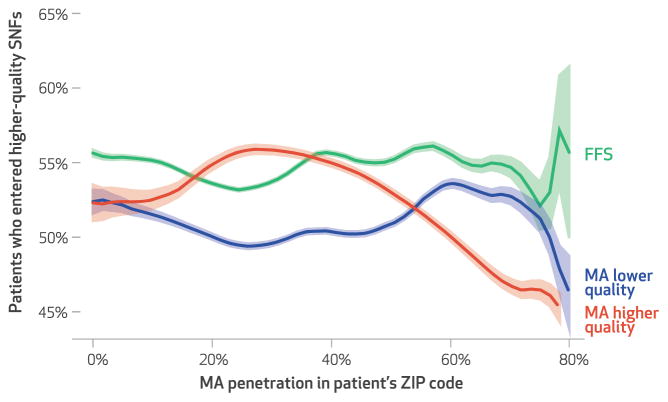

To examine evidence of differential selection based on geography, we first examined at the ZIP code level the percentage of enrollees in FFS Medicare and higher- and lower-quality MA plans who went to a higher-quality SNF. We assumed that patients within the same ZIP code would have access to similar SNFs of similar quality. We arrayed these percentages by ZIP code–level MA penetration to see if SNF selection in ZIP codes with greater penetration differed from that in areas with less penetration.

In our primary analysis, we used linear regression to examine the effect of MA plan enrollment on patient selection of higher- and lower-quality SNFs by star rating and on SNF rehospitalization rate, controlling for beneficiary residential ZIP code (using fixed effects) and other patient characteristics. Using ZIP code fixed effects allowed us to look at the relationship between enrollment status and the star ratings of SNFs selected by beneficiaries apart from the influence of geography. Adjusting for patient characteristics allowed us to control for other factors that might have played a role in guiding a patient to a SNF.

To address the possibility of a simultaneous impact of SNF characteristics on a beneficiary’s SNF selection, and to determine what factors most influenced SNF selection, we estimated the star ratings of nursing homes selected by beneficiaries using a McFadden choice model,37,38 which has been used for similar purposes in previous studies.12,13,35 From a given neighborhood (ZIP code), patients have a set of alternative SNFs (choice set) to choose from. In choosing a SNF, patients explicitly consider specific facility characteristics but also choose based on a general sense of the SNF, which may reflect other underlying characteristics.12,13,35 Patients’ caregivers or providers may also make these decisions, based on different characteristics. Our goal was to assess how the influence of SNF characteristics on this selection differed between MA and FFS Medicare enrollees. For example, if MA plans are preferentially contracting with lower-quality SNFs, given all other SNF characteristics, a higher-quality SNF will have a higher likelihood of admitting an FFS Medicare patient than an MA patient from same neighborhood.

Based on previous literature,12,13,35 we defined a choice set for each patient as all SNFs within twenty-two kilometers of the patient’s ZIP code, the fifteen closest SNFs, and any SNF that any other resident of that ZIP code selected. We fit a conditional logit regression model with each observation representing a patient choice. The outcome of interest was a binary variable with a value of 1 indicating the SNF that each patient actually chose and 0 representing unselected choices. Using MA enrollment interaction terms, we estimated the differential effects of a SNF’s characteristics on the probability that a patient would select that SNF. We present these results as the marginal effect of a one-unit change in a characteristic on the probability of selecting a SNF.

In all of our models, we used inverse probability weighting derived from propensity scores to adjust for patient differences across FFS and MA plans. Details on the choice model and weighting methodologies are in the online appendix.39

Additional sensitivity analyses stratified results into subgroups for hip fracture patients, stroke patients, patients not dually eligible, higher and lower MA concentration in the residential ZIP code, and individual years. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 14.

LIMITATIONS

Our study was subject to several limitations. First, if the overall star rating of a SNF on Nursing Home Compare is not actually linked to patient health outcomes, then the difference between Medicare Advantage and FFS Medicare in this study might not matter.

Second, we were unable to study detailed hospital claims for MA and FFS patients, so we could not check for differences in chronic conditions not measured in the MDS. However, as mentioned above, the MDS information is widely considered to be a valid measure of patient status.

Finally, we did not have information on actual contracts between MA plans and SNFs. Nonetheless, we could infer these relationships based on the SNFs that MA enrollees actually used.

Study Results

Exhibit 1 shows descriptive characteristics of the patient sample before weighting. After applying inverse probability weights, we found minimal differences among patients by enrollment type.

Exhibit 1.

Unadjusted characteristics of the patient sample, by Medicare enrollment type

| Characteristic | Enrollment type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| FFS | MA lower quality | MA higher quality | |

| Number | 3,335,476 | 945,885 | 302,761 |

| Average age (years) | 80.84 | 80.02 | 80.83 |

| Female | 62.45% | 63.11% | 63.13% |

| Black | 7.57% | 10.39% | 6.80% |

| Hispanic | 3.28% | 5.67% | 5.78% |

| Fully dual eligible | 15.52% | 14.00% | 11.25% |

| Partially dual eligible | 4.01% | 7.17% | 4.32% |

| Married | 36.94% | 38.73% | 39.97% |

| Baseline score on the ADL scalea | 17.12 | 16.84 | 16.91 |

| Baseline score on the CPSb | 1.36 | 1.27 | 1.27 |

| Baseline diagnosis of: | |||

| Stroke | 10.32% | 11.24% | 10.51% |

| Cancer | 10.24 | 9.33 | 9.50 |

| Alzheimer disease | 4.21 | 3.90 | 3.99 |

| Dementia | 17.02 | 15.96 | 15.36 |

| Hip fracture | 8.09 | 9.07 | 9.71 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.33 |

| Congestive heart failure | 19.63 | 18.45 | 18.50 |

| Diabetes | 29.93 | 32.12 | 30.80 |

| Schizophrenia | 0.75 | 0.48 | 0.39 |

| Bipolar disorder | 1.16 | 1.06 | 1.15 |

| Aphasia | 1.53 | 1.60 | 1.53 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2012–14 from the Minimum Data Set, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, and Nursing Home Compare. NOTES Baseline refers to the patient’s admission to the facility. FFS is fee-for-service Medicare. “MA lower quality” refers to MA plans given fewer than four stars by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and “MA higher quality” refers to the plans with four or five stars. Fully dual eligible patients typically have Medicaid pay for more Medicare services and also receive additional benefits not covered by Medicare. Partially dual eligible patients have some Medicare services paid for by Medicaid. The specifics of these arrangements vary state to state.

A measure of a patient’s ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs) independently. See note 33 in text.

Cognitive Performance Scale, a measure of a patient’s cognitive ability. See note 34 in text.

Exhibit 2 displays patterns of SNF selection arranged by MA penetration in patients’ ZIP code areas. We assumed that if there were no selection effect of Medicare Advantage, the three lines would be identical because patients in the same ZIP code would have access to SNFs of the same quality. Instead, we found that across most ZIP codes, FFS Medicare beneficiaries tended to use higher-quality SNFs.

Exhibit 2. Percentages of fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare and Medicare Advantage (MA) patients who entered a higher-quality skilled nursing facility (SNF), by percentage of MA penetration in the patient’s residential ZIP code.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2012–14 from the Minimum Data Set, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, and Nursing Home Compare. NOTES Higher-quality SNFs are rated four or five stars by Nursing Home Compare. “MA low quality” and “MA high quality” are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals.

Exhibit 3 presents the adjusted differences in the characteristics of the average SNF chosen by FFS and MA beneficiaries, controlling for patients’ characteristics and residential ZIP code fixed effects. Enrollees in both lower- and higher-quality MA plans were admitted to SNFs that had significantly lower overall star ratings and significantly higher adjusted rehospitalization rates. Notably, 4.22 percentage points fewer enrollees in lower-quality MA plans and 2.46 percentage points fewer enrollees in higher-quality MA plans who were admitted to a SNF during the study period went to a higher-quality SNF. Additionally, lower quality MA enrollees entered SNFs with significantly higher rehospitalization rates compared to FFS enrollees (0.13 percentage points higher for enrollees in lower-quality MA plans). MA enrollees also typically entered larger SNFs (6.5 and 7.7 more beds for lower- and higher-quality MA plans, respectively) and SNFs with more Medicaid-paid residents (3.0 percent and 2.5 percent greater shares of the SNF population for lower- and higher-quality MA plans, respectively).

Exhibit 3.

Adjusted differences in quality characteristics of skilled nursing facilities chosen by fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare versus Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees

| Characteristic | Adjusted mean | Adjusted difference from FFS Medicare | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| MA lower quality | MA higher quality | ||

| Star rating for: | |||

| Health inspection | 3.75 | −0.01 | 0.06** |

| Staffing | 3.42 | −0.11*** | −0.05*** |

| Quality measures | 2.98 | −0.01 | 0.06** |

| Overall | 3.47 | −0.13*** | −0.08** |

| Facilities with overall rating of 4 or 5 | 54.71% | −4.22*** | −2.46** |

| Adjusted rehospitalization rate | 17.56% | 0.16*** | 0.00 |

| Number of beds | 127.54 | 6.51*** | 7.65*** |

| Medicare-paid residents | 26.18% | −3.27*** | −3.97*** |

| Medicaid-paid residents | 47.52% | 3.01*** | 2.50*** |

| MA residents | 18.92% | 3.38*** | 4.68*** |

| Part of a chain | 57.27% | 0.04*** | 0.03*** |

| For profit | 68.53% | 0.05*** | 0.02*** |

| Beds occupied | 83.96% | 0.05 | 0.24 |

| Hospital based | 7.64% | −0.01*** | −0.01** |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2012–14 from the Minimum Data Set (MDS), Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, and Nursing Home Compare. NOTES Differences were estimated with patient characteristics and residential ZIP code fixed effects controlled for. “MA lower quality” and “MA higher quality” are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. All star rating scales range from 1 to 5 stars. p values are based on robust standard errors clustered by state.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

Exhibit 4 shows the marginal effect of a one-unit increase in each variable from the choice-model analysis. A more detailed table of model coefficients is in the appendix.39 When we looked at quality indicators, we found that an increase of one star in the overall star rating of a given SNF increased the likelihood of an average FFS patient entering that SNFby 0.45 percent, while the likelihood was increased by only 0.12 percent for patients in lower-quality MA plans and 0.11 percent for those in higher-quality plans. Similarly, a 1 percent increase in the adjusted rehospitalization rate decreased the likelihood of an average FFS patient to enter a given SNF by 1.63 percent but increased the likelihood of a patient in a lower-quality MA plan to enter that SNF by 2.38 percent. The results from the sensitivity analyses followed similar trends.

Exhibit 4.

Marginal changes in skilled nursing facility (SNF) selection, by nursing home characteristics

| Characteristic | Marginal effect (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| FFS | MA lower quality | MA higher quality | |

| Distance from patient’s residence | −1.02 | −0.95 | −1.04 |

| Number of beds | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Share of Medicare-paid residents | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Share of Medicaid-paid residents | −0.10 | −0.08 | −0.10 |

| Share of MA residents | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.29 |

| Beds occupied | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Hospital based | 0.59 | 2.30 | 1.29 |

| Multifacility | 0.57 | 1.17 | 1.04 |

| For profit | 0.64 | 2.35 | 1.48 |

| Adjusted rehospitalization rate | −1.63 | 2.38 | 1.19 |

| Overall star rating | 0.45 | 0.12 | 0.11 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2012–14 from the Minimum Data Set, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, and Nursing Home Compare. NOTES “MA lower quality” and “MA higher quality” are explained in the notes to exhibit 1. The marginal effects show the change in probability of going to a given SNF if the relevant characteristic changes by one unit. For example, a 1 percent increase in a SNF’s adjusted rehospitalization rate decreases the likelihood that an average FFS Medicare patient would entering this SNF by 1.63 percent and increases the likelihood that a beneficiary in an MA low plan would enter it by 2.38 percent.

Discussion

Overall, we found that MA enrollees were differentially admitted to lower-quality SNFs than FFS patients were. This effect was robust to patients’ characteristics, patients’ residential ZIP codes, and the availability of facility choices for patients. Given the choices a given beneficiary makes when selecting a SNF, MA patients who are members of plans with either higher or lower star ratings are less sensitive to lower ratings and have a lower probability of going to a higher-quality facility, compared to FFS beneficiaries. We also found that among MA enrollees, the likelihood of selecting a poor-quality SNF (based on rehospitalization rates or star ratings) was greater for members of lower-quality MA plans relative to members of higher-quality plans. This may indicate that higher-quality MA plans guide patients toward relatively higher-quality SNFs than lower-quality MA plans do.

We found that the percentage of SNF residents who were dually eligible for Medicaid was not a significant predictor of SNF selection. While there may be some differences between network designs of MA contracts that serve primarily Medicaid patients, we were not able to detect a difference in our analysis.

One other recent study that sought to evaluate the differential quality of SNFs selected by MA beneficiaries compared to FFS Medicare beneficiaries found little difference between the two groups.40 That study did not implement a choice model and therefore did not take into account all of the potential SNFs that a beneficiary had to choose from. Our analysis makes an important contribution in that it finds that, after adjustment for a patient’s distance to a SNF and for all of the available SNFs in a beneficiary’s area, MA enrollees were not as strongly influenced by SNF quality as FFS Medicare enrollees were.

We hypothesize that several factors may have led to these findings. FFS enrollees are not limited by network design when selecting a SNF. Given a wider range of choices, FFS enrollees (and agents involved in making a SNF selection on their behalf) may be influenced more by publicly available measures of quality, while MA enrollees might be limited by SNF networks established by MA plans. A recent qualitative study found that on hospital discharge, FFS patients were often given large lists of nearby facilities for making their selection, while MA enrollees were given a more limited list of facilities or were assigned a facility by a MA contract administrator.41 When guiding patients to a SNF, MA plans may be more influenced by past relationships with SNFs and physicians who practice there, and might not be as strongly influenced by quality when making network decisions.

It is challenging to quantify the overall effects on the health outcomes of MA beneficiaries going to SNFs with lower star ratings, compared to FFS beneficiaries. The measures used to calculate the overall star rating have been correlated with patient health outcomes,42–44 but no studies demonstrate what a one-star improvement in overall SNF star ratings leads to in patient outcomes. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that in a plan of 1,000 MA enrollees, up to 42 fewer patients would enter a higher-quality SNF than in a sample of 1,000 FFS patients. Given that about 20 percent of SNF residents are rehospitalized, the differences in rates for MA patients may be quite large.32

What can be done to ensure that MA plans contract with higher-quality SNFs? CMS’s rehospitalization measures for SNFs do not include MA patients in their calculations. Including MA patients in these measures could help better track any differences in outcomes between FFS and MA SNF patients. Also, CMS could require MA plans to be more transparent about the quality of SNFs in their networks when beneficiaries make their Medicare enrollment decisions. Additionally, including SNF outcomes in HEDIS star ratings might encourage MA plans to contract with higher-quality SNFs.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that Medicare Advantage enrollees appear more likely than FFS Medicare enrollees to enter lower-quality skilled nursing facilities. After we adjusted for distance and other choice factors, MA plan enrollees were less predisposed to choose higher-quality SNFs, given the option. This indicates that MA plans may be influencing beneficiary decision making around nursing home selection. As MA plans continue to attract a larger share of the Medicare population relative to FFS Medicare, more information on the nursing home decisions made by MA plan enrollees and the outcomes of those choices are of vital policy importance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (Nursing Home Selection of Medicare Advantage Patients and Its Implications on Health Outcomes, Grant No. R03G050002; The Emerging Role of MA in Nursing Homes, Grant No. R014G047180; Shaping Long-Term Care in America, Grant No. P01AG027296; and Cost-Sharing, Use, and Outcomes of Post-Acute Care in Medicare Advantage Plans, Grant No. R01).

Footnotes

An earlier version of this article was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 25, 2017.

The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Contributor Information

David J. Meyers, Doctoral student in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island

Vincent Mor, Professor in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health, and a health scientist at the Providence Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Momotazur Rahman, Assistant professor in the Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice, Brown University School of Public Health.

NOTES

- 1.Jacobson G, Casillas G, Damico A, Neuman T, Gold M. Medicare Advantage 2016 spotlight: enrollment market update [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. May 11, [cited 2017 Nov 13]. (Issue Brief). Available from: http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-2016-spotlight-enrollment-market-update/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson JC, Phibbs CS. An evaluation of Medicaid selective contracting in California. J Health Econ. 1989;8(4):437–55. doi: 10.1016/0167-6296(90)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber J, McKnight R. Controlling health care costs through limited network insurance plans: evidence from Massachusetts state employees [Internet] Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2014. Sep, [cited 2017 Nov 13]. (NBER Working Paper No. 20462). Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w20462.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepard M. Hospital network competition and adverse selection: evidence from the Massachusetts health insurance exchange [Internet] Cambridge (MA): National Bureau of Economic Research; 2016. Sep, [cited 2017 Nov 13]. (NBER Working Paper No. 22600). Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w22600.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polsky D, Weiner J. The skinny on narrow networks in health insurance marketplace plans [Internet] Philadelphia (PA): University of Pennsylvania, Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics; 2015. Jun 23, [cited 2017 Nov 13]. (Data Brief). Available from: http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=ldi_databriefs. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson JC. Hospital tiers in health insurance: balancing consumer choice with financial incentives. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;(Suppl Web Exclusives):W3-135–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindrooth RC, Norton EC, Dickey B. Provider selection, bargaining, and utilization management in managed care. Econ Inq. 2002;40(3):348–65. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chernew ME, Fendrick AM. Improving benefit design to promote effective, efficient, and affordable care. JAMA. 2016;316(16):1651–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobson G, Trilling A, Neuman T, Damico A, Gold M. Medicare Advantage hospital networks: how much do they vary? [Internet] Menlo Park (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2016. Jun, [cited 2017 Nov 13]. Available from: http://insurance.maryland.gov/Consumer/Documents/agencyhearings/KaiserReport-Medicare-Advantage-Hospital-Networks-How-Much-Do-They-Vary.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pear R. New York Times. 2013. Sep 22, Lower health insurance premiums to come at cost of fewer choices. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy [Internet] 2017 Mar; Available from: http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_entirereport.pdf.

- 12.Rahman M, Foster AD. Racial segregation and quality of care disparity in US nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2015;39:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenfeld AJ, Zhang X, Grabowski DC, Mor V, Weissman JS, Rahman M. Hospital-skilled nursing facility referral linkage reduces readmission rates among Medicare patients receiving major surgery. Surgery. 2016;159(5):1461–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kane RA, Kling KC, Bershadsky B, Kane RL, Giles K, Degenholtz HB, et al. Quality of life measures for nursing home residents. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(3):240–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith DB, Feng Z, Fennell ML, Zinn JS, Mor V. Separate and unequal: racial segregation and disparities in quality across U.S. nursing homes. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26(5):1448–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno JM, Miller SC. Driven to tiers: socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. Milbank Q. 2004;82(2):227–56. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(10):1675–81. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambassi G, Landi F, Peng L, Brostrup-Jensen C, Calore K, Hiris J, et al. Validity of diagnostic and drug data in standardized nursing home resident assessments: potential for geriatric pharmacoepidemiology. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology. Med Care. 1998;36(2):167–79. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199802000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mor V. A comprehensive clinical assessment tool to inform policy and practice: applications of the Minimum Data Set. Med Care. 2004;42(4, Suppl):III50–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000120104.01232.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landi F, Tua E, Onder G, Carrara B, Sgadari A, Rinaldi C, et al. Minimum Data Set for home care: a valid instrument to assess frail older people living in the community. Med Care. 2000;38(12):1184–90. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mor V, Berg K, Angelelli J, Gifford D, Morris J, Moore T. The quality of quality measurement in U.S. nursing homes. Gerontologist. 2003;43(Spec2):37–46. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.CMS.gov. Part C and D performance data [Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [last modified 2017 Nov 2; cited 2017 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/PerformanceData.html. [Google Scholar]

- 24.LTCfocus [home page on the Internet] Providence (RI): Brown University; [cited 2017 Nov 13]. Available from: http://ltcfocus.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medicare.gov. About Nursing Home Compare Data[Internet] Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; [cited 2017 Nov 13]. Available from: https://www.medicare.gov/NursingHomeCompare/Data/About.html. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schapira MM, Shea JA, Duey KA, Kleiman C, Werner RM. The Nursing Home Compare report card: perceptions of residents and caregivers regarding quality ratings and nursing home choice. Health Serv Res. 2016;51(Suppl 2):1212–28. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuman MD, Wirtalla C, Werner RM. Association between skilled nursing facility quality indicators and hospital readmissions. JAMA. 2014;312(15):1542–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Konetzka RT, Polsky D, Werner RM. Shipping out instead of shaping up: rehospitalization from nursing homes as an unintended effect of public reporting. J Health Econ. 2013;32(2):341–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Konetzka RT, Grabowski DC, Perraillon MC, Werner RM. Nursing home 5-star rating system exacerbates disparities in quality, by payer source. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(5):819–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werner RM, Norton EC, Konetzka RT, Polsky D. Do consumers respond to publicly reported quality information? Evidence from nursing homes. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):50–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dulal R. Cost efficiency of nursing homes: do five-star quality ratings matter? Health Care Manag Sci. 2017;20(3):316–25. doi: 10.1007/s10729-016-9355-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rahman M, Grabowski DC, Mor V, Norton EC. Is a skilled nursing facility’s rehospitalization rate a valid quality measure? Health Serv Res. 2016;51(6):2158–75. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54(11):M546–53. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.m546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care. 2017;55(9):e68–72. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rahman M, Foster AD, Grabowski DC, Zinn JS, Mor V. Effect of hospital-SNF referral linkages on rehospitalization. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 1):1898–919. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robusto CC. The cosine-haversine formula. Am Math Mon. 1957;64(1):38–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. In: Zarembka P, editor. Frontiers in econometrics. New York (NY): Academic Press; 1974. pp. 105–42. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McFadden D. Modeling the choice of residential location. In: Karlqvist A, Lundqvist L, Snickars F, Weibull J, editors. Spatial interaction theory and planning models. Amsterdam: North Holland; 1978. pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- 39.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 40.Chang E, Ruder T, Setodji C, Saliba D, Hanson M, Zingmond DS, et al. Differences in nursing home quality between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(10):960e9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tyler DA, Gadbois EA, McHugh JP, Shield RR, Winblad U, Mor V. Patients are not given quality-of-care data about skilled nursing facilities when discharged from hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(8):1385–91. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukamel DB. Risk-adjusted outcome measures and quality of care in nursing homes. Med Care. 1997;35(4):367–85. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199704000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Intrator O, Zinn J, Mor V. Nursing home characteristics and potentially preventable hospitalizations of long-stay residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1730–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Intrator O, Grabowski DC, Zinn J, Schleinitz M, Feng Z, Miller S, et al. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: the effects of states’ Medicaid payment and bed-hold policies. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1651–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00670.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]