Abstract

Objectives

Moderate alcohol consumption is protective against rheumatoid arthritis (RA) development and associated with lower levels of systemic inflammation in RA and in the general population. We therefore hypothesised that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with less severe local inflammation in joints in RA, detected by MRI. Since asymptomatic persons can have low-grade MRI-detected inflammation, we also hypothesised that alcohol consumption is associated with the extent of MRI inflammation in asymptomatic volunteers.

Methods

188 newly presenting patients with RA and 192 asymptomatic volunteers underwent a unilateral contrast-enhanced 1.5T MRI of metacarpophalangeal, wrist and metatarsophalangeal joints. The MRIs were scored on synovitis, bone marrow oedema and tenosynovitis; the sum of these yielded the MRI inflammation score. MRI data were evaluated in relation to current alcohol consumption, categorised as non-drinkers, consuming 1–7 drinks/week, 8–14 drinks/week and >14 drinks/week. Association between C reactive protein (CRP) level and alcohol was studied in 1070 newly presenting patients with RA.

Results

Alcohol consumption was not associated with the severity of MRI-detected inflammation in hand and foot joints of patients with RA (P=0.55) and asymptomatic volunteers (P=0.33). A J-shaped curve was observed in the association between alcohol consumption and CRP level, with the lowest levels in patients consuming 1–7 drinks/week (P=0.037).

Conclusion

Despite the fact that moderate alcohol consumption has been shown protective against RA, and our data confirm a J-shaped association of alcohol consumption with CRP levels in RA, alcohol was not associated with the severity of joint inflammation. The present data suggest that the pathophysiological mechanism underlying the effect of alcohol consists of a systemic effect that might not involve the joints.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, alcohol consumption, magnetic resonance imaging, inflammation, asymptomatic volunteers

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

A J-shaped association between alcohol and C reactive protein was confirmed in the present study.

What does this study add?

Alcohol was not associated with the extent of local inflammation in joints.

Introduction

In the general population moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with lower levels of systemic inflammation, as several studies have shown that alcohol consumption is associated with levels of C reactive protein (CRP) in a J-shaped or U-shaped manner.1 2 Individuals with an alcohol consumption of one to two drinks daily had the lowest CRP levels.

In rheumatoid arthritis (RA), the influence of alcohol consumption on the risk of developing RA has been studied extensively. Moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with a decreased risk of developing RA.3–5 The risk of developing RA was lowest in persons who consumed approximately 1 unit of alcohol per day.3 In patients with RA, alcohol consumption was associated with lower levels of inflammatory markers (eg, CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, soluble tumour necrosis factor receptor II, interleukin-6 (IL-6)).6–8 For IL-6 levels a U-shaped association was also observed, with the lowest IL-6 levels in patients with RA who consumed 1 unit of alcohol per day.6

Within RA the effect of alcohol on local inflammation in joints has been studied once using the swollen joint count (SJC), and no evident association between alcohol consumption and the number of swollen joints was observed in 1238 patients with RA.9 Because MRI is more sensitive than the SJC in detecting local inflammation,10 we anticipated that MRI is useful in detecting an effect of alcohol on the severity of local inflammation in RA.

Furthermore, as the effect of alcohol on markers of systemic inflammation is also present in the general population,1 and since some asymptomatic persons of the general population also have low-graded MRI-detected inflammation,11 12 an association between alcohol and joint inflammation might not be confined to patients with RA, but even be present in asymptomatic volunteers.

Therefore, we hypothesised that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with less inflammation in hand and foot joints, visualised by MRI, both in patients with RA and in asymptomatic volunteers. The present study evaluated these two hypotheses. Furthermore, to validate the previously observed association between alcohol consumption and CRP level in RA, we also studied this association in our cohort of patients with RA.

Methods

Participants

The patients with RA studied were consecutively included in the Leiden Early Arthritis Clinic (EAC). This is an inception cohort that includes patients with ≥1 swollen joint and a symptom duration of <2 years. When patients presented to the outpatient clinic, questionnaires were obtained that included a self-reported average number of alcohol consumptions per week (current consumption); information on the type of alcohol was not available. Furthermore, physical examination (among which 66 SJC) was performed and blood samples were obtained.13 RA was defined as fulfilling the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria during the first year of follow-up. From 1993 to 2016, 1244 patients with RA were included in the EAC cohort. The association between alcohol consumption and CRP was assessed in all patients with RA of whom alcohol consumption was available (1070 patients with RA). From 2010 onwards MRI was added to the study protocol,10 and the association between alcohol and MRI-detected inflammation was assessed in 188 consecutive patients with RA who underwent an MRI at baseline (see online supplementary figure 1 for a flow chart).

rmdopen-2017-000577supp001.docx (38.4KB, docx)

The asymptomatic volunteers were recruited between November 2013 and December 2014, and have been described earlier.12 Volunteers were recruited via advertisements on local newspapers and websites. Volunteers had no history of RA or other inflammatory rheumatic diseases, no joint symptoms during the last month and no clinically detectable arthritis at physical examination. Questionnaires were obtained, including self-reported alcohol consumption. CRP levels were not assessed in these volunteers. One hundred and ninety-three volunteers underwent an MRI; in one of these persons, no data on alcohol consumption were obtained. The volunteers received a voucher of €20 to compensate for their time and travel costs and did not receive a report of the MRI. Therefore, volunteers had no/limited benefit from participating.

All participants have given a written informed consent.

MRI protocol and scoring

A contrast-enhanced MRI was performed of the unilateral metacarpophalangeal (MCP) 2–5 joints, wrist joints and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) 1–5 joints. In the EAC the most painful side was scanned, or in case of equally severe symptoms at both sides the dominant side was scanned. In asymptomatic volunteers the dominant side was scanned. All persons were asked to stop non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs at least 24 hours prior to the MRI scan. The MRI scans were made prior to the start of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (including corticosteroids). An ONI MSK Extreme 1.5T extremity MRI scanner (GE, milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) was used. The scan protocol is described in more detail in the online supplementary methods. Briefly, T1-weighted sequences were acquired. After intravenous contrast administration (gadoteric acid, Guerbet, Paris, 0.1 mmol/kg) T1-weighted sequences with fat saturation (T1Gd) were performed. The foot was scanned with T2-weighted fat-saturated (T2) and T1 sequences in the first 106 patients with RA and with T1Gd in the last 82 patients with RA. Scoring of synovitis and bone marrow oedema (BME) was done according to the RA MRI score (RAMRIS) method in the MCP, wrist and MTP joints.14 Tenosynovitis was scored according to Haavardsholm et al 15 in the MCP joints and wrist. The total MRI inflammation score was calculated by summing the synovitis, BME and tenosynovitis scores, and ranged between 0 and 189. MRI scoring was done independently by trained readers; patients with RA were scored by two readers (WPN and ECN), and the asymptomatic volunteers were scored by another two readers (HWvS and LM). Readers were blinded for any clinical data. Furthermore, to exclude observer bias introduced by knowledge that persons had no symptoms, the MRI images of asymptomatic volunteers were mixed with the MRI images of patients with RA and patients with arthralgia without clinical synovitis (n=99). The within-reader intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) of the readers were all greater than 0.93, and the between-reader ICCs of the four readers were all above 0.91. The mean scores of the two readers were used for the analyses.

rmdopen-2017-000577supp002.docx (24KB, docx)

Analyses

Alcohol consumption was categorised into four groups: non-drinkers, participants who consume 1–7 drinks/week, 8–14 drinks/week and >14 drinks/week, and this corresponded to no, one, two and more drinks daily as used in some previous studies.3–6 Groups were compared with the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. The association of alcohol consumption with MRI-detected inflammation was analysed using univariable and multivariable linear regressions adjusted for age, gender, smoking status and anticitrullinated protein antibody (ACPA). ACPA was not assessed in asymptomatic volunteers, and the multivariable linear regression in the asymptomatic volunteers was adjusted for age, gender and smoking status. In the linear regression analyses, MRI inflammation scores were log10-transformed (log10(score +1)) to approximate a normal distribution. To analyse whether a J shape existed in the association between alcohol consumption and CRP levels, a linear regression with a piecewise linear spline on one alcohol consumption per week was used as this fitted the data best. SPSS V.23.0.0 was used for analysis.

Results

Patients

Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. Sixty-four per cent (n=121) of patients with RA who underwent MRI (see online supplementary figure 1 for a flow chart) consumed alcohol at baseline, with a median consumption of 6 drinks/week (IQR 3–11). Of the asymptomatic volunteers, 70% (n=135) consumed alcohol, with a median consumption of 7 drinks/week (IQR 4–14). Patients with RA consumed on average one alcohol consumption less than the asymptomatic volunteers; this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.14).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with RA and asymptomatic volunteers in which hand and foot MRIs were performed and patients with RA in which CRP was analysed

| Patients with RA with an MRI n=188 |

Asymptomatic volunteers n=192 |

Patients with RA with CRP measurement n=1070 |

|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 56 (14) | 50 (16) | 56 (15) |

| Female, n (%) | 121 (64.4) | 135 (70.3) | 717 (67.0) |

| Symptom duration in weeks, median (IQR) | 15.4 (7.9–29.6) | NA | 18.4 (9.1–35.6) |

| CRP in mg/L, median (IQR) | 10.0 (3.8–23.5) | NA | 14.0 (6.0–33.0) |

| SJC, median (IQR) | 6 (3–10) | NA | 8 (4–13) |

| ACPA positivity, n (%) | 102 (54.3) | NA | 550 (52.6) |

| RF positivity, n (%) | 116 (61.7) | NA | 604 (56.9) |

| Current smokers, n (%) | 50 (28.4) | 17 (8.8) | 271 (25.7) |

| Patients consuming alcohol, n (%) | 121 (64.4) | 135 (69.9) | 621 (58.0) |

| Units/week, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–10.5) | 7.0 (4.0–14.0) | 6.0 (2.0–10.5) |

Of patients with RA with an MRI, smoking status and SJC were missing in 12 and 18 patients, respectively. In patients with RA with a CRP measurement, smoking status, SJC, RF and ACPA status were missing in, respectively, 17, 38, 9 and 24 patients with RA.

ACPA, anticitrullinated protein antibody; CRP, C reactive protein; NA, not assessed; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; SJC, swollen joint count.

Association of MRI-detected inflammation with alcohol consumption in patients with RA

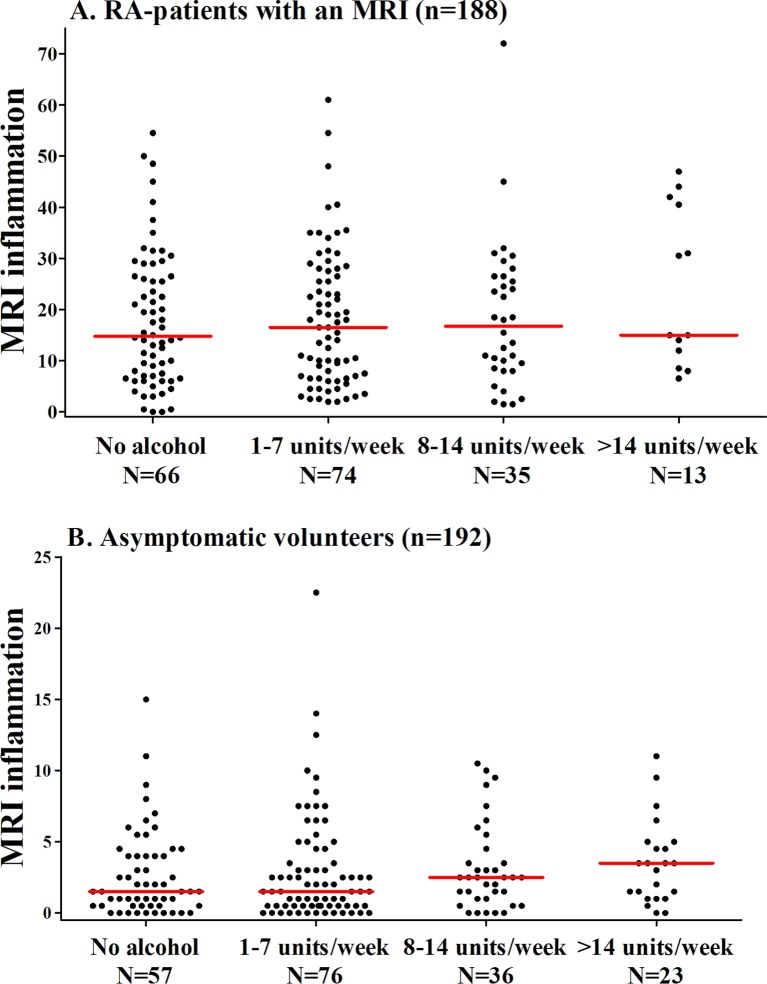

The extent of MRI-detected inflammation was first compared in four categories of alcohol consumption. The median MRI-detected inflammation in patients with RA did not significantly differ between the four categories: patients with RA who did not drink alcohol had a median MRI inflammation score of 14.8 (IQR=7.0–26.5), patients with RA consuming 1–7 drinks/week had a median of 16.5 (IQR=7.0–27.5), patients with RA consuming 8–14 drinks/week had a median of 16.8 (IQR=8.5–26.5), and patients with RA consuming >14 drinks/week had a median of 15.0 (IQR=12.0–40.5) (P=0.53) (figure 1A). When analysing BME, synovitis and tenosynovitis separately, similar results were seen (see figure 2).

Figure 1.

The association between alcohol consumption and the severity of MRI-detected inflammation in hand and foot joints of (A) patients with RA and (B) asymptomatic volunteers. The lines presented in the figure represent median values. MRI-detected inflammation does not differ significantly between the four groups in patients with RA and asymptomatic volunteers (P=0.53 and P=0.33, respectively). RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

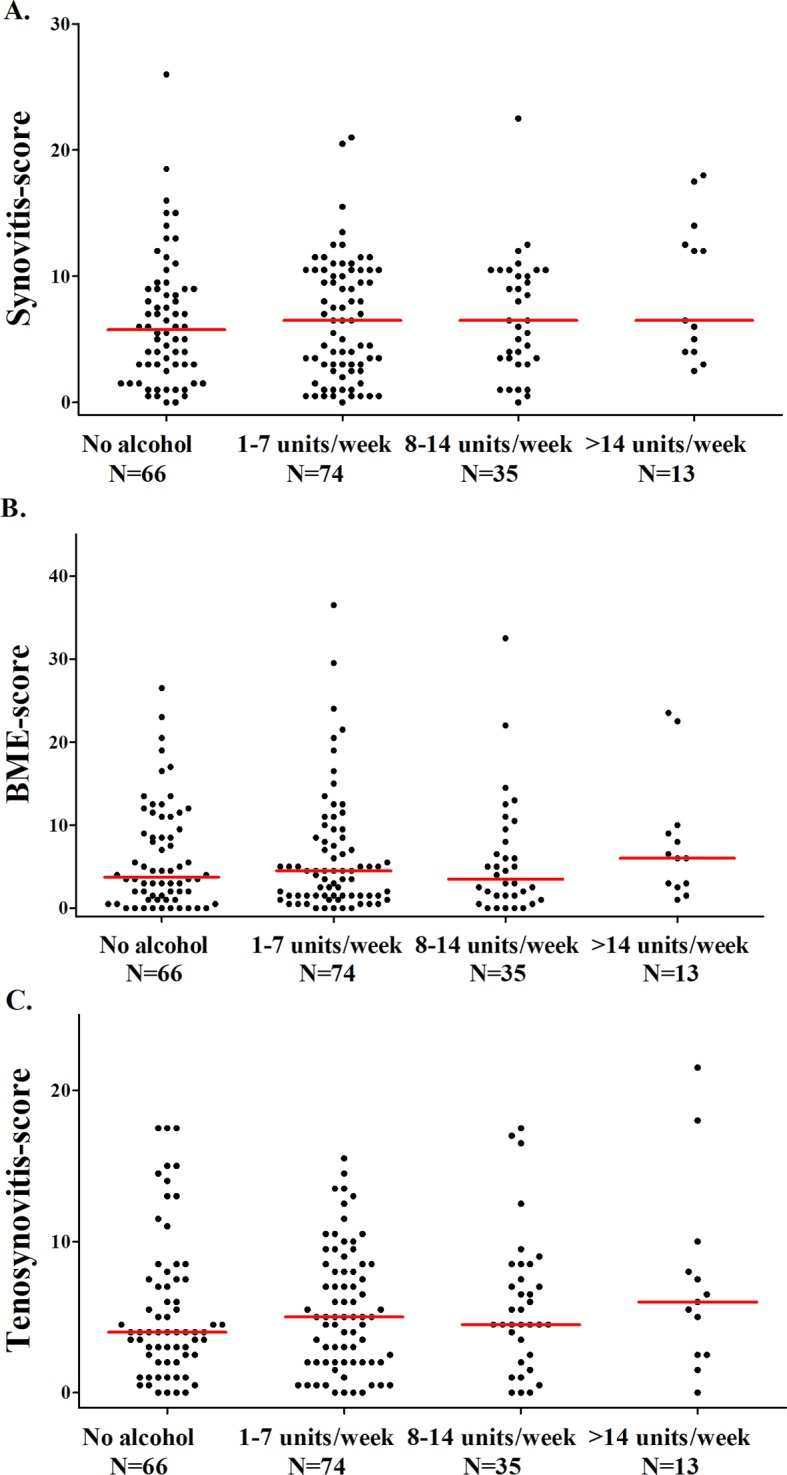

Figure 2.

The association between alcohol consumption and the severity of (A) synovitis, (B) BME and (C) tenosynovitis in patients with RA. The lines presented in the figure represent median values. Synovitis, BME and tenosynovitis scores did not differ significantly between the four groups in patients with RA (P=0.60, P=0.47 and P=0.85, respectively). BME, bone marrow oedema; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

The association between alcohol and MRI-detected inflammation was also evaluated, with the number of alcohol consumptions on a continuous scale also showing no association (β=1.011, 95% CI 0.992 to 1.030, P=0.36). To exclude the possibility of non-significance due to the presence of confounders, the analysis was subsequently adjusted for age, gender, smoking and ACPA. Also, this showed no association between alcohol and inflammation in hand and foot joints (β=0.994, 95% CI 0.975 to 1.013, P=0.53).

Association of MRI-detected inflammation with alcohol consumption in asymptomatic volunteers

In asymptomatic volunteers, the extent of MRI-detected inflammation was also compared in four categories of alcohol consumption. The median MRI-detected inflammation did not significantly differ between the four categories: asymptomatic volunteers who did not drink alcohol had a median MRI inflammation score of 1.5 (IQR=0.5–4.0), 1–7 drinks/week 1.5 (IQR=0.5–4.0), 8–14 drinks/week 2.5 (IQR=1.0–4.0) and >14 drinks/week 3.5 (IQR=1.0–5.0) (P=0.33) (figure 1B). Analysing BME, synovitis and tenosynovitis separately revealed similar results (see figure 3).

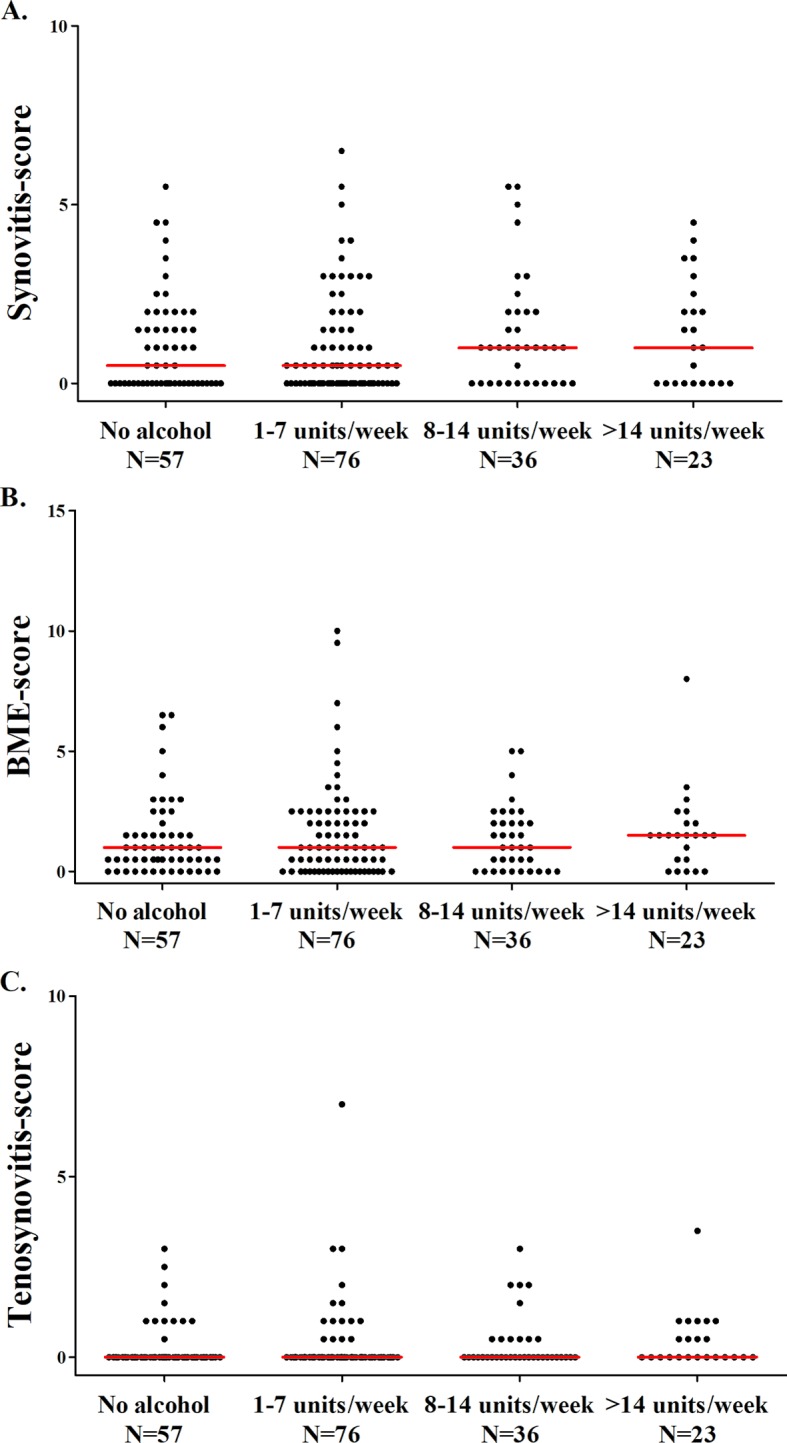

Figure 3.

The association between alcohol consumption and the severity of (A) synovitis, (B) BME and (C) tenosynovitis in asymptomatic volunteers. The lines presented in the figure represent median values. Synovitis, BME and tenosynovitis scores did not differ significantly between the four groups in asymptomatic volunteers (P=0.81, P=0.44 and P=0.15, respectively). BME, bone marrow oedema.

Assessing alcohol consumption on a continuous scale, an association was observed in univariable analysis (β=1.018, 95% CI 1.002 to 1.034, P=0.025). However, after adjusting for age, the association disappeared (β=1.003, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.016, P=0.62), and also after adjusting for age, gender and smoking status no association was observed (β=1.002, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.015, P=0.76).

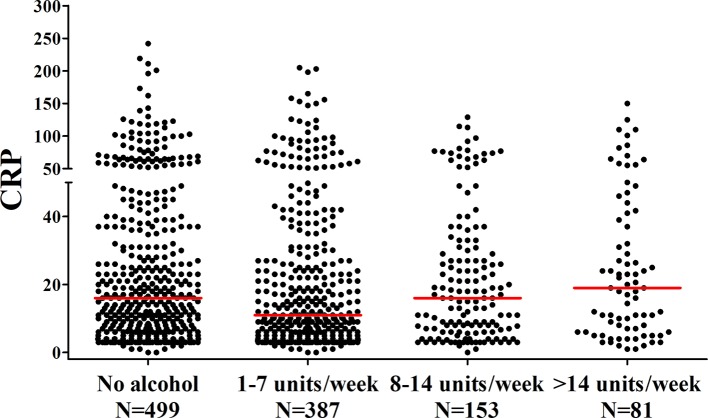

Association of alcohol consumption and CRP in patients with RA

Because of the negative findings done thus far, we searched for a positive control and we wished to verify if the previously observed association between alcohol consumption and CRP was present in our cohort of patients with RA. In a total of 1070 patients with RA, 58% consumed alcohol, with a median consumption of 6 drinks/week (IQR=2–11). The median CRP level in non-drinkers was 16 mg/L (IQR=6–37 mg/L), in patients who consume 1–7 drinks/week the median was 11 mg/L (IQR=5–29 mg/L), in patients who consume 8–14 drinks/week the median was 16 mg/L (IQR=6–31 mg/L), and in patients who consume >14 drinks/week the median was 19 mg/L (IQR=6–41 mg/L). The median CRP levels between these four groups differed significantly (P=0.043). Evaluation by eye suggested the presence of a J-shaped effect, with the lowest CRP in the group that consumes 1–7 drinks/week. Indeed comparing this group with the non-drinkers revealed a significant difference (P=0.011, figure 4). To further confirm this J-shaped effect, a piecewise linear spline regression was used. The regression was divided into two regression coefficients of the J curve (eg, the left decreasing part (compared with no drinks/week), and the right increasing part with the lowest CRP level on 1 drink/week). One drink/week was chosen as this corresponded to the lowest CRP levels. Indeed this piecewise regression showed that CRP level decreased significantly with increasing alcohol consumption up until a maximum of 1 drink/week (β=0.80, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.93, P=0.003). In patients consuming >1 drink/week, CRP levels increased significantly with increasing alcohol consumption (β=1.015, 95% CI 1.004 to 1.025, P=0.006). Hereby, the visually observed J-shaped association was statistically confirmed. In a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, gender, smoking and ACPA status, the downward part of the J curve was still present (β=0.85, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.99, P=0.039), but the upward part of the J curve lost its statistical significance (β=1.007, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.017, P=0.214). A beta of 1.007 indicates that for every drink/week increase in alcohol consumption, there is an 1.007-fold increase in CRP level; thus, in patients consuming >1 drink/week higher alcohol consumption was associated with a higher CRP level.

Figure 4.

The association between alcohol consumption and CRP levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The lines presented in the figure represent median values. CRP differs significantly between the groups (P=0.043). CRP, C reactive protein.

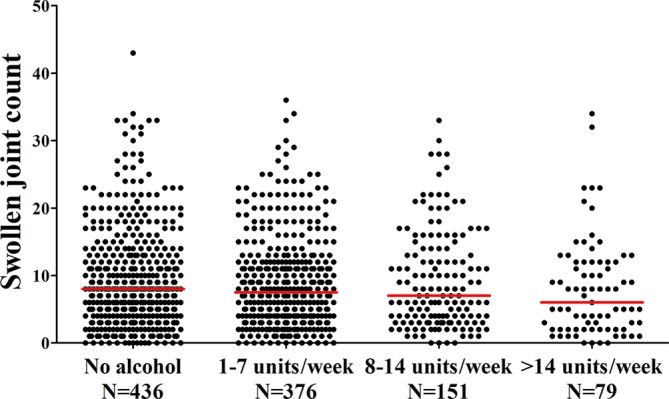

Finally the number of swollen joints in these patients at disease presentation was studied in relation to alcohol consumption. No association was observed (figure 5).

Figure 5.

The association between alcohol consumption and SJC in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The lines presented in the figure represent median values. A 66 SJC was evaluated. The SJC does not differ significantly between the groups (P=0.23). SJC, swollen joint count.

Discussion

Moderate alcohol consumption has been associated with less severe systemic inflammation (generally measured using CRP levels) in the general population.1 2 Also within patients with RA, it has been shown repeatedly that moderate alcohol consumption lowers the risk of developing RA and is associated with less severe systemic inflammation.3 4 Because of these findings, we hypothesised that moderate alcohol consumption might also be associated with less severe inflammation in joints, which can be sensitively detected with MRI. The current data revealed no association between alcohol consumption and the severity of local inflammation in hand and foot joints on MRI. Similar to a previous study, we also found no association with the number of swollen joints. Thus, although moderate alcohol consumption is associated with lower levels of systemic inflammation and a lower risk to develop RA, based on the present findings it is not associated with less severe inflammation in joints.

The pathophysiological mechanism underlying the association between alcohol consumption and inflammation is unknown. Different studies explored the immunoregulatory effects of alcohol and various results have been observed. High alcohol consumption has been reported to be associated with depleted cell-mediated and humoral immune responses,16 whereas other data suggest that low alcohol consumption has a stimulatory effect on the cellular immune response.17 Furthermore, higher alcohol consumption was observed to associate with lower levels of tumour necrosis factor receptor II and IL-6,6 whereas moderate alcohol consumption (7–14 units/week) associated with increased levels of IL-2, IL-4 and IL-10, cytokines that are known for anti-inflammatory activities.17 In addition, a U-shaped association between alcohol consumption and IL-6 levels is reported.6 These findings are in line with the observed association between alcohol and the systemic inflammatory marker CRP.

Distinguishing high alcohol consumption from moderate alcohol consumption has several pitfalls. In this study, assessment of alcohol consumption is based on questionnaires and could therefore deviate from the true alcohol consumption. Information on alcohol usage was collected by the number of drinks, assuming common portion sizes: beer (1 glass or bottle), wine (4-ounce glass) and liquor (1 drink or shot). This is similar as done by others, and the alcohol content is estimated to be 10–15 g per drink.18 In addition we did not collect information on the type of alcohol, which is a limitation. Previous large studies have revealed that most persons drink more than one type of alcohol, which makes stratification difficult.1 Furthermore there is controversy on the importance of the type of beverage. Although it has been suggested that the protective effect of alcohol on systemic markers of inflammation is confined to red wine, several studies investigating this issue did not find different effects for different types of alcohol.19–22 Although we cannot make conclusions for different beverages, the fact that the association of alcohol consumption and CRP levels in this study resembles the associations found in the literature1 supports the validity of the data on alcohol consumption.

Alcohol consumption is part of a lifestyle and might therefore be a proxy for other factors associated with lifestyle. So the association of alcohol on joint inflammation might have been influenced by other factors. Multivariate analyses were performed to adjust for some of these factors (among others, age and smoking), but this did not majorly influence the study results.

The lack of association between alcohol consumption and the extent of local joint inflammation on MRI found in this study might have been caused by an inadequate power to detect an effect of alcohol on joint inflammation on MRI, especially as the previously observed effect of alcohol on systemic inflammatory markers, such as CRP levels, was generally observed in very large studies.1 MRI is more time-consuming and more expensive to perform than, for example, CRP level measurements, making an MRI study within thousands of patients with RA infeasible. In our view there was not even a trend towards an association between alcohol and local inflammation; furthermore, in the total group of 1070 patients, alcohol did also not associate with the number of clinically swollen joints. Altogether this makes it unlikely that the present finding is falsely negative.

The present study in early RA had a cross-sectional study design. This allowed us to perform measurements before disease-modifying treatment was initiated. A longitudinal study is needed to evaluate the association between alcohol and long-term outcome of RA, but current treatments and treat-to-target strategies may mask an effect of alcohol (if it is present) on the course of RA.

According to the European Society of Musculoskeletal Radiology recommendations, BME was evaluated on T1Gd. The RAMRIS method suggests to use T2, but T2 was omitted from our scan protocol since previous studies have shown that these sequences perform equally well to depict BME,23 24 and a T1Gd has already been used to assess synovitis and tenosynovitis. This allowed a shorter imaging time for the participants.

Healthy, asymptomatic volunteers can also have some subclinical inflammation in hand and foot joints, especially at older age. The nature of this inflammation is incompletely clear. Immunosenescence or degeneration may play a role. Although the origin is incompletely known, we speculated that a potential effect of alcohol on joint inflammation might also be present in persons without RA. But similar to patients with RA, alcohol did not influence the severity of subclinical inflammation in hand and foot joints of asymptomatic volunteers.

In conclusion, moderate alcohol consumption has been shown to have a beneficial effect on the risk of RA development and inflammatory markers, and the present study confirmed a J-shaped association between alcohol and CRP, and we observed no association between alcohol and the extent of local inflammation in joints. Therefore the present data suggest that the pathophysiological mechanism underlying the effect of alcohol consists of a systemic effect that might not involve the joints.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge EC Newsum for scoring the MRIs of the EAC cohort.

Footnotes

Contributors: LM, HWvS, WPN, MR and AHMvdH-vM contributed to the conception and design of this study. LM, WPN and HWvS contributed to the acquisition of the data. LM, WPN and AHMvdH-vM analysed and interpreted the data. LM and AHMvdH-vM drafted the manuscript, and WPN, HWvS and MR revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (Vidi grant).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The medical ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Imhof A, Froehlich M, Brenner H, et al. . Effect of alcohol consumption on systemic markers of inflammation. Lancet 2001;357:763–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. Alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation 2003;107:443–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000045669.16499.EC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jin Z, Xiang C, Cai Q, et al. . Alcohol consumption as a preventive factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1962–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott IC, Tan R, Stahl D, et al. . The protective effect of alcohol on developing rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2013;52:856–67. 10.1093/rheumatology/kes376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Källberg H, Jacobsen S, Bengtsson C, et al. . Alcohol consumption is associated with decreased risk of rheumatoid arthritis: results from two Scandinavian case-control studies. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:222–7. 10.1136/ard.2007.086314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lu B, Solomon DH, Costenbader KH, et al. . Alcohol consumption and markers of inflammation in women with preclinical rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3554–9. 10.1002/art.27739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huidekoper AL, van der Woude D, Knevel R, et al. . Patients with early arthritis consume less alcohol than controls, regardless of the type of arthritis. Rheumatology 2013;52:1701–7. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maxwell JR, Gowers IR, Moore DJ, et al. . Alcohol consumption is inversely associated with risk and severity of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2010;49:2140–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bergman S, Symeonidou S, Andersson ML, et al. . Alcohol consumption is associated with lower self-reported disease activity and better health-related quality of life in female rheumatoid arthritis patients in Sweden: data from BARFOT, a multicenter study on early RA. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:218 10.1186/1471-2474-14-218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Krabben A, Stomp W, Huizinga TW, et al. . Concordance between inflammation at physical examination and on MRI in patients with early arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:506–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mangnus L, Schoones JW, van der Helm-van Mil AH. What is the prevalence of MRI-detected inflammation and erosions in small joints in the general population? A collation and analysis of published data. RMD Open 2015;1:e000005 10.1136/rmdopen-2014-000005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mangnus L, van Steenbergen HW, Reijnierse M, et al. . Magnetic resonance imaging-detected features of inflammation and erosions in symptom-free persons from the general population. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:2593–602. 10.1002/art.39749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Rooy DP, van der Linden MP, Knevel R, et al. . Predicting arthritis outcomes--what can be learned from the leiden early arthritis clinic? Rheumatology 2011;50:93–100. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Østergaard M, Edmonds J, McQueen F, et al. . An introduction to the EULAR-OMERACT rheumatoid arthritis MRI reference image atlas. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64(Suppl 1):i3–7. 10.1136/ard.2004.031773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haavardsholm EA, Østergaard M, Ejbjerg BJ, et al. . Introduction of a novel magnetic resonance imaging tenosynovitis score for rheumatoid arthritis: reliability in a multireader longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1216–20. 10.1136/ard.2006.068361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. MacGregor RR. Alcohol and immune defense. JAMA 1986;256:1474–9. 10.1001/jama.1986.03380110080031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Romeo J, Wärnberg J, Nova E, et al. . Changes in the immune system after moderate beer consumption. Ann Nutr Metab 2007;51:359–66. 10.1159/000107679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mostofsky E, Mukamal KJ, Giovannucci EL, et al. . Key findings on alcohol consumption and a variety of health outcomes from the Nurses’ Health Study. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1586–91. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levitan EB, Ridker PM, Manson JE, et al. . Association between consumption of beer, wine, and liquor and plasma concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in women aged 39 to 89 years. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:83–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ. Wine, beer, and spirits: are they really horses of a different color? Circulation 2002;105:2806–7. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000022344.79651.CC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Shaper G, et al. . The effects of different alcoholic drinks on lipids, insulin and haemostatic and inflammatory markers in older men. Thromb Haemost 2003;90:1080–7. 10.1160/TH03-04-0221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Imhof A, Woodward M, Doering A, et al. . Overall alcohol intake, beer, wine, and systemic markers of inflammation in western Europe: results from three MONICA samples (Augsburg, Glasgow, Lille). Eur Heart J 2004;25:2092–100. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stomp W, Krabben A, van der Heijde D, et al. . Aiming for a shorter rheumatoid arthritis MRI protocol: can contrast-enhanced MRI replace T2 for the detection of bone marrow oedema? Eur Radiol 2014;24:2614–22. 10.1007/s00330-014-3272-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mayerhoefer ME, Breitenseher MJ, Kramer J, et al. . STIR vs. T1-weighted fat-suppressed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of bone marrow edema of the knee: computer-assisted quantitative comparison and influence of injected contrast media volume and acquisition parameters. J Magn Reson Imaging 2005;22:788–93. 10.1002/jmri.20439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2017-000577supp001.docx (38.4KB, docx)

rmdopen-2017-000577supp002.docx (24KB, docx)