Abstract

Interspecies transmissions of avian influenza viruses (AIV) occur at the human-poultry interface, among which the live poultry markets (LPMs) are easily assessed by urban residents. Thousands of live poultry from different farms arrive daily at wholesale markets before being sold to retail markets. We assessed the risk of AIV downwind spread via airborne particles from a representative wholesale market in Guangzhou. Air samples were collected using the cyclone-based NIOSH bioaerosol samplers at different locations inside a wholesale market, and viral RNA and avian 18S RNA were quantified using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling was performed to investigate the AIV spread pattern. Viral RNA was readily detected from 19 out of 21 air sampling events, predominantly from particles larger than 1 µm. The concentration of viral RNA detected at the poultry holding area was 4.4 × 105 copies/m3 and was as high as 2.6 × 104 copies/m3 100 m downwind. A high concentration of avian 18S RNA (2.5 × 108 copies/m3) detected at the poultry holding area was used for assessing the potential spread of avian influenza virus during outbreak situations. CFD modeling indicated the combined effect of wind direction and surrounding buildings on the spread of virus and a slow decay rate of the virus in the air in the downwind direction. Because of the large volume of poultry trade daily, wholesale markets located in urban areas may pose considerable AIV infection risk to neighboring residents via wind spread, even in the absence of direct contact with poultry.

Keywords: Avian influenza virus, downwind spread, avian 18S RNA, airborne transmission, CFD modeling, NIOSH bioaerosol sampler

1. Introduction

Zoonotic infections by avian influenza viruses (AIV) are a significant public health threat due to their pandemic potential (Chen et al., 2013, Su et al., 2015, Peiris et al., 2016). Among the various AIV subtypes that have been reported to infect humans, H5N1 and H7N9 subtypes have caused 859 and 1533 laboratory-confirmed human infections with 53% and 39% fatality rates as of June 2017, respectively (FAD, 2017, WHO, 2017). Epidemiological studies suggest recent poultry exposure as the major risk factor for zoonotic infections because the H5N1 or H7N9 viruses have not acquired the ability to transmit among humans (Cowling et al., 2013).

Among different human-poultry interfaces, live poultry markets (LPMs) are known to have an important role in AIV amplification through dynamic poultry mixing and onward dissemination to humans (Peiris et al., 2016). Although LPMs allow for human-poultry contact, the transmission modes of avian influenza viruses from birds to humans at LPMs have not been fully elucidated. Surveillance studies have demonstrated that genetically diverse AIV are highly prevalent in birds and are frequently detected from environmental surfaces at LPMs (Choi et al., 2004, Nguyen et al., 2005, Lau et al., 2007, Garber et al., 2007), which support the feasibility of contact transmission. However, the possibility of airborne transmission of avian influenza viruses at LPMs cannot be excluded because several studies have detected viral RNA or infectious AIV in air at the human-avian interface. Chen et al. (2009) reported viral RNA in air sampled from a wet poultry market in Taiwan. Jonges et al. (2015) detected viral RNA in air inside and outside poultry farms during H9N2 and H10N9 outbreaks. During the 1983–84 H5N2 outbreak in the United States, high-volume air sampling outside of affected poultry areas detected AIV in samples taken up to 45 m away from chicken farms but not at further distances (Swayne, 2009). During the H7N3 outbreak in Canada, infectious viruses were detected via low-volume air sampling inside barns with infected poultry, and a low concentration of virus genes was detected by PCR outside the affected barns (Swayne, 2009). We and others also recently reported the detection of viral RNA and isolation of infectious AIV from air sampled at LPMs in Guangdong, China (Wu et al., 2016, Zhou et al. 2016). In addition, Cowling et al. (2013) reported that 75% of the 130 patients infected with H7N9 and 71% of the 43 patients with H5N1 had recent exposure to poultry. Is it possible that the other patients were infected by airborne routes?

LPMs are essential for maintaining the poultry supply chain in China. Bulk trades are made at wholesale markets where thousands of live poultry from different farms arrive before being sold to retail markets. Because these wholesale markets are often located within urban areas, the potential exposure risk for neighboring residents has not been fully described. Studies on the size of virus-laden particles are lacking. In addition, although viruses were detected in the air in LPMs, the virus dispersion pattern inside and beyond the market is not well characterized. In this study, we assessed the risk of downwind spread of AIV via airborne particles from a wholesale market in Guangzhou using empirical air sampling in combination with Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modeling to analyze the potential AIV spread pattern.

2. Materials and Methods

Description of the wholesale market

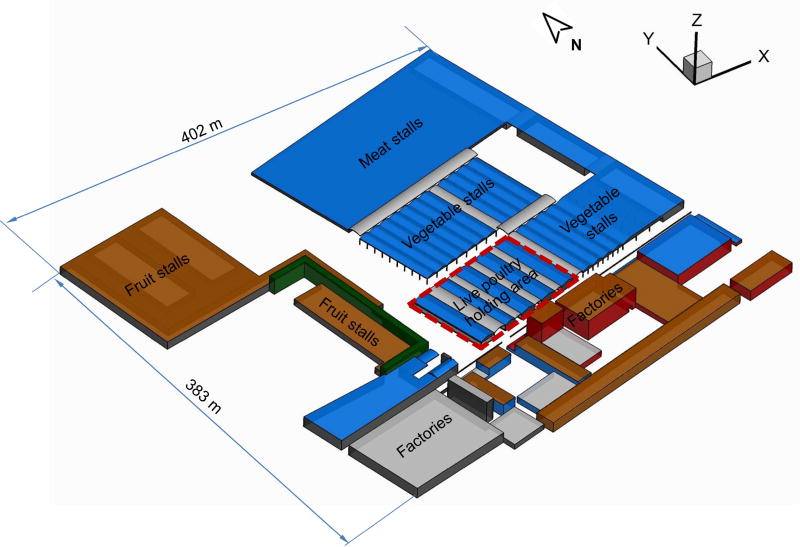

We sampled air from one out of six wholesale markets in Guangzhou, which is divided into different functional regions for live poultry holding area, dressed poultry stalls, vegetable stalls, seafood stalls, meat stalls, fruit stalls, etc. Approximately 10,000 to 20,000 live poultry are held daily in five large henhouses 8 m high and 70 m in length (Figure 1). To the south of the live poultry holding area (−y direction) is an industrial zone with two buildings 20 m high. The fruit stalls are to the west of the live poultry holding area, and to the north and east are the vegetable and the meat markets, respectively.

Figure 1.

Outlook of the wholesale market where the poultry market is located inside. Five henhouses are located in the live poultry holding area. Most buildings are about 8 m in height, except a few industrial buildings that are as tall as 20 m.

Environmental air sampling

Aerosol samples around the poultry market were collected using cyclone-based NIOSH bioaerosol samplers (model BC251) provided by Dr. William Lindsley from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The NIOSH samplers can collect particles from three size categories (i.e., >4 µm, 1–4 µm, and <1 µm) with a designated flow rate of 3.5 L/min (Lindsley et al., 2006). The sampler was mounted on a tripod and set 1.2 m above the floor. Sampling lasted for 30 min, and a total of 0.105 m3 air was collected. The negative control was an NIOSH sampler placed on the same tripod without turning on the air pump. To resuspend virus particles collected from air, 1 mL of MEM with 4% BSA was added to each of the collection tubes and PTFE filters.

Three experiments were independently performed on December 10, 2015, February 24, 2016, and July 26, 2016, with seven NIOSH samplers used for each experiment. Detailed information on the location of the NIOSH samplers are summarized in Table 1–3 and Figure 2. Wind direction and velocity were available from the nearest weather station (about 3 km from the wholesale market) at the beginning of the experiment, and sampling points were mostly chosen downstream of the live poultry areas. Sampling points inside the henhouse and between henhouses were also necessary to characterize the maximum virus concentrations. Temperature and relative humidity (RH) were recorded during the sampling period.

Table 1. Air sampling results from Experiment A at the wholesale market.

Air sampling was performed on December 10, 2015. The recorded temperature was 22.5 °C, 65% relative humidity, and Northern wind at 1.4 m/s.

| Sample Point No. |

Concentrations of influenza virus M gene, copies/m3 (influenza subtype detected) |

Concentrations of 18s RNA, copies/m3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | |

| 1 | Neg* | 1.1 × 105 (H9) | 3.1 × 105 (H9) | 5.9 × 105 | 3.0 × 107 | 2.2 × 108 |

| 2 | Neg | 1.6 × 104 (H9) | 2.1 × 105 (H9) | 2.1 × 105 | 1.6 × 107 | 1.7 × 108 |

| 3 | Neg | Neg | 2.9 × 103 (H9) | 5.8 × 105 | 5.4 × 105 | 3.4 × 106 |

| 4 | Neg | 1.0 × 104 (H9) | 3.4 × 103 (H9) | 5.2 × 104 | 1.2 × 106 | 7.5 × 106 |

| 5 | Neg | 1.3 × 104 (H9) | 5.6 × 104 (H9) | 3.6 × 105 | 1.5 × 107 | 6.0× 107 |

| 6 | Neg | 6.7 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 3.6 × 103 (H9) | 6.9 × 104 | 9.3 × 105 | 3.9 × 106 |

| 7 | Neg | Neg | 2.7 × 104 (H9) | 1.7 × 105 | 6.5 × 105 | 5.1 × 106 |

Neg = Negative

Table 3. Air sampling results from Experiment C at the wholesale market.

Air sampling was performed on July 26, 2016. The recorded temperature was 31.0°C, 68.7% relative humidity, and Southestern wind at 1 m/s.

| Sample Point No. |

Concentrations of influenza virus M gene, copies/m3 (influenza subtype detected) |

Concentrations of 18s RNA, copies/m3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | |

| 1 | Neg | 3.1 × 102 (Non-H5/7/9) | 2.4 × 104 (H9) | 2.4 × 104 | 2.8 × 106 | 1.6 × 107 |

| 2 | 1.8 × 102 (Non-H5/7/9) | Neg | 2.2 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 2.8 × 104 | 1.1 × 106 | 1.3 × 107 |

| 3 | Neg | 2.6 × 102 (Non-H5/7/9) | 1.2 × 105 (H9) | 8.2 × 103 | 4.2 × 105 | 1.5 × 107 |

| 4 | Neg | Neg | 1.0 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 2.0 × 103 | 6.3 × 104 | 1.4 × 106 |

| 5 | Neg | Neg | 6.4 × 102 (Non-H5/7/9) | 9.9 × 103 | 1.5 × 105 | 6.9 × 106 |

| 6 | Neg | Neg | Neg | 1.4 × 103 | 2.3 × 104 | 1.6 × 105 |

| 7 | Neg | Neg | Neg | 1.2 × 104 | 2.8 × 104 | 8.4 × 106 |

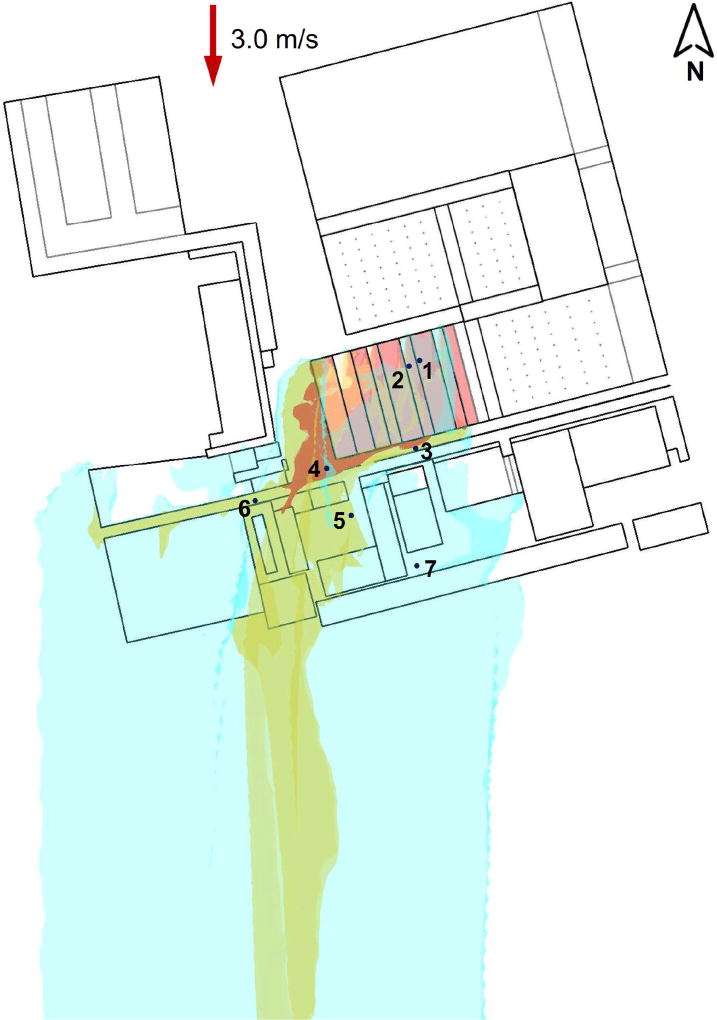

Figure 2.

The predicted spread pattern of virus-laden aerosol (using tracer gas as a surrogate) in the wholesale market: (a) northerly wind, 1.4 m/s; (b) northerly wind, 3.0 m/s; (c) southeasterly wind, 1.0 m/s. The values for the three iso-surfaces are 0.1 (red), 0.005 (orange), and 1 × 10−5 (blue).

Detection and quantification of influenza A virus M and 18S RNA genes by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted by RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers and probes targeting influenza A virus M genes used the WHO protocol for influenza surveillance (WHO, 2015) and AgPath-ID One-Step RT-PCR Reagents (Life Technologies) were used. Ribosomal RNA, the central component of the ribosome is abundant and well-conserved in most cells. Therefore, 18S RNA is a suitable housekeeping gene to quantify RNA shedding from avian species. Specific primers targeting the conserved region of poultry 18S RNA are described elsewhere (Kuchipudi et al., 2012). QuantiTech SYBR Green RT-PCR reagents were used.

The influenza A virus M or 18S RNA gene copies per cubic meter (m3) air were calculated by the following equation:

| (1) |

where ρ is the concentration of M or 18S RNA gene copies in the air sample RNA elution, E is the volume of the elution, Vw is the volume of MEM used to wash the collection tube, Vr is the volume of specimen subject to RNA extraction, Q is the airflow rate, and t is the duration of operation.

The minimum linear range of quantification (LoQ) was set as 2 copies/µL. Thus, the LoQ were determined as 8,163 copies/m3 air. The samples that were positive for influenza A virus M genes were further subtyped to H5, H7, H9, or non-H5/H7/H9 subtypes by real-time PCR. Specific primers and probes targeting HA segments were adapted from the WHO and China CDC protocols (Kang et al., 2015, Li, 2006).

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) modelling

The geometry of the wholesale market was reconstructed for the CFD simulation, as illustrated in Figure 1. Because the market was quite large, buildings located far away from the poultry holding area (e.g., the dressed poultry stalls and the seafood stalls over 250 m to the north) were not included. The CFD simulations were conducted using the commercial software FLUENT with the RNG k-ε turbulence model, which is robust to solve problems associated with the wind velocity field around buildings, and to predict particle dispersion by airflow (Chen, 2009; Wei and Li, 2015). The final computational mesh contained 11.6 million tetrahedral cells after careful grid independent tests. At the domain inlet, the vertical profiles for streamwise velocity u(z), turbulent kinetic energy k(z), and its dissipation rate ε(z) were defined by the following equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

where UH is the reference velocity at the reference height H (H = 10 m), and this velocity was obtained from the nearest weather station; u* = 0.24 m/s is the friction velocity; Cµ = 0.09 is a model constant; and κ = 0.41 is Von Karman’s constant.

The velocity field was obtained, and then the species transport equation was solved, where tracer gas was chosen as the surrogate for the particles released from the henhouses. Five henhouses were set as uniform sources of AIV viral RNA and 18S RNA-laden particles. The study used the second-order upwind scheme for all the variables except pressure for the RANS equations and discretization of pressure was based on a staggered scheme PRESTO. The SIMPLE algorithm was employed to couple the pressure and momentum equations.

3. Results

Detection of AIV viral RNA and avian 18S rRNA in air

Only H9 subtype influenza viruses were detected in our three sampling events. Influenza virus M gene was detected from the >4 µm size fraction in 19/21 NIOSH air samplers from three independent sampling events − 7/7 in experiment A, 7/7 in experiment B, and 5/7 in experiment C (Table 1–3). Among the 21 NIOSH samplers, 12/21 detected AIV RNA at the 1–4 µm size fraction and only 3/21 detected AIV RNA at submicron sizes.

The highest concentration of viral RNA was 4.4 × 105 copies/m3 (Point A1) detected inside the live poultry holding area. The detected concentration was higher than a previously reported value of 8.5 × 104 copies/m3 detected inside the turkey barn during an H10N9 outbreak (Jonges et al., 2015). The virus concentration was as high as 2.6 × 104 copies/m3 at Point B7, which was approximately 100 m away from the live poultry holding area. Our results suggest that visitors or residents near the wholesale market may be under a considerable AIV exposure risk even without any direct contact with poultry.

Avian 18S RNA was detected in all size categories during the three experiments. The highest concentration detected was 2.5 × 108 copies/m3 (at sampling point A1). A higher quantity of 18S RNA was detected from particles >4 µm, which was 2 orders higher than that of the 1–4 µm particles, and 3 orders high than that detected from <1 µm particles.

The spread pattern of fine virus particles

Figure 2 shows three dimensional iso-surfaces of modeled relative concentrations of tracer gas under three prevailing wind scenarios. They are normalized by dividing the tracer concentration at sampling point 1 in each model to eliminate the effect of the choice of source strength, and to allow a comparison of results from different models.

The concentration of tracer gas is high at locations close to the poultry market. It spreads both in a streamwise direction and laterally owing to the combined effects of the wind direction and surrounding buildings. The concentration decays as the tracer gas is diluted by the surrounding air. The spread patterns in Figure 2a and 2b are similar in spite of the different wind magnitudes. However, the tracer gas becomes more diluted with a stronger wind, and correspondingly, the 18S RNA concentration at sampling point 1 is two orders higher in Experiment A than in Experiment B.

The surrounding buildings have a considerable effect on the spread of the tracer gas. They enhance its lateral spread, and a wider range of downstream buildings is exposed. On the other hand, the highest concentration zone is not necessarily located on the downstream side of the poultry market. For example, in Figure 2c, the high industrial buildings create air circulation, and backward flow causes the tracer gas to spread against the wind.

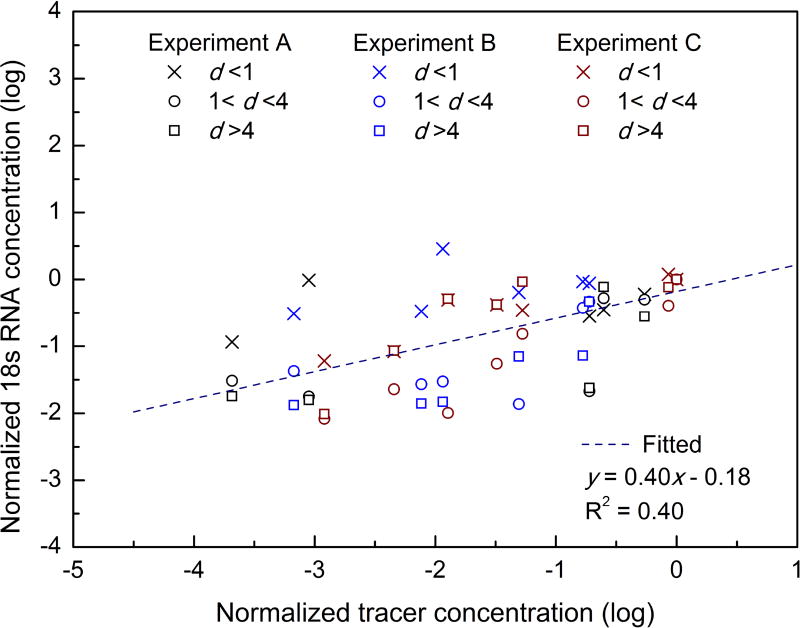

Coupling experimental and numerical results

Predicting tracer gas concentrations in the wholesale market is challenging because the geometry of the wholesale market is complex – the wind direction and magnitude may not be exactly the same as provided by the weather station and is changing all the time, and the movement of vehicles and people in the market might influence the spread of tracer gas, etc. For example, the predicted tracer concentration at sampling point A4 is zero, but we detected both virus and 18S RNA; dense vehicle traffic and population flow from the poultry market to sampling point A4 was observed during our sampling period on December 10, 2015, which was a bazaar day. Excluding sampling point A4, all other points were correlated between 18S RNA and tracer concentrations as shown in Figure 3. Despite many variables that potentially influence the relationship between emission of particles and concentration, a reasonably good correlation between field measurements and modeled tracer gas concentration was observed. In a previous study on wind-mediated spread of avian influenza virus (Jonges et al., 2015), the atmospheric dispersion model produced a better correlation between the measured endotoxin concentration and predicted particle dispersion (R2> 0.6), but complex building geometry was not considered. CFD modeling in this study indicated the important effect of surrounding buildings on influenza virus spread around the poultry holding area.

Figure 3.

Correlation between measured 18S RNA concentration and predicted tracer concentration; both variables were normalized by the values at sampling point 1.

4. Discussion

Avian Influenza viruses of high concentrations were readily detectable in our sampling events, but H5N1 or H7N9 subtypes were absent. It was interesting that particles smaller than 1 µm carried a negligible number of viruses compared to the larger particles in the wholesale market. Measurements on human cough-generated aerosols revealed that those smaller than 1 µm contain nearly half of the total viruses (Lindsley et al., 2010). This discrepancy might result from different particle generation mechanisms during human cough and in the poultry holding area, and low pathogenic avian influenza viruses are mainly shed through the enteric route (Spickler et al., 2008).

The NIOSH samplers collected AIV RNA from particles >4 µm as far as 100 m downwind from the live poultry holding area, suggesting that particles of this size range could travel far. The terminal settling velocities of particles with aerodynamic diameters of 5 µm and 10 µm are 0.74 mm/s and 2.96 mm/s, respectively (Wei and Li, 2015). These particles take more than 22 min and 5 min, respectively, to settle by a distance of 1 m in a still environment.

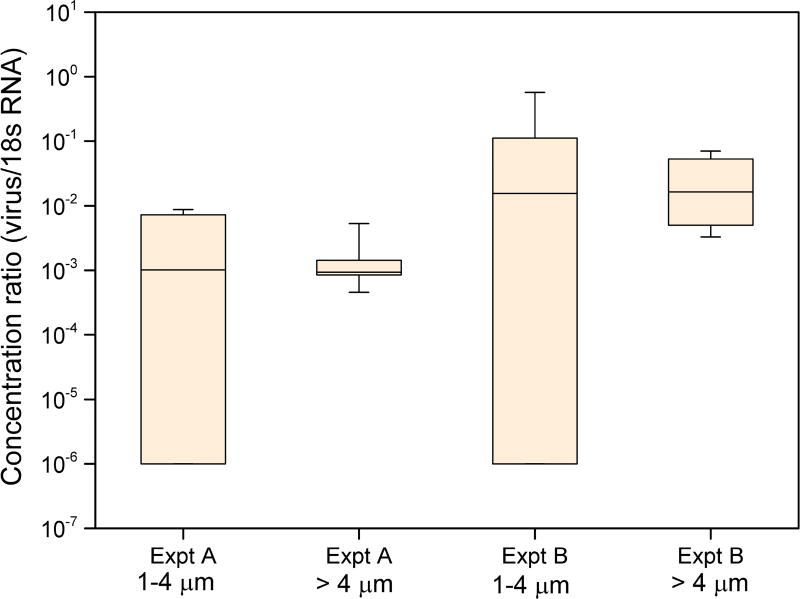

Avian 18S RNA is unique to poultry, which may be a better indicator for estimating downwind spread of avian influenza virus under an outbreak scenario as high viral load in air is expected. As shown in Figure 4, the median value of the concentration ratio of virus to 18S RNA is similar in the same experiment, but the deviation is much larger for 1–4 µm particles because the virus concentration is mostly below the linear range of quantification. This matches well with the results from our previous study (Zhou et al., 2016). In addition, it is obvious that the virus shedding rate from poultry was higher in experiment B (Feb. 24, 2016; T = 13.4 °C) than in experiment A (Dec. 10, 2015; T = 22.5 °C).

Figure 4.

Ratio of the virus concentration to 18S RNA concentration in Experiment A and B. Counts below the limit of detection are represented as 10−7 on the log scale. The box indicates 25th and 75th percentile.

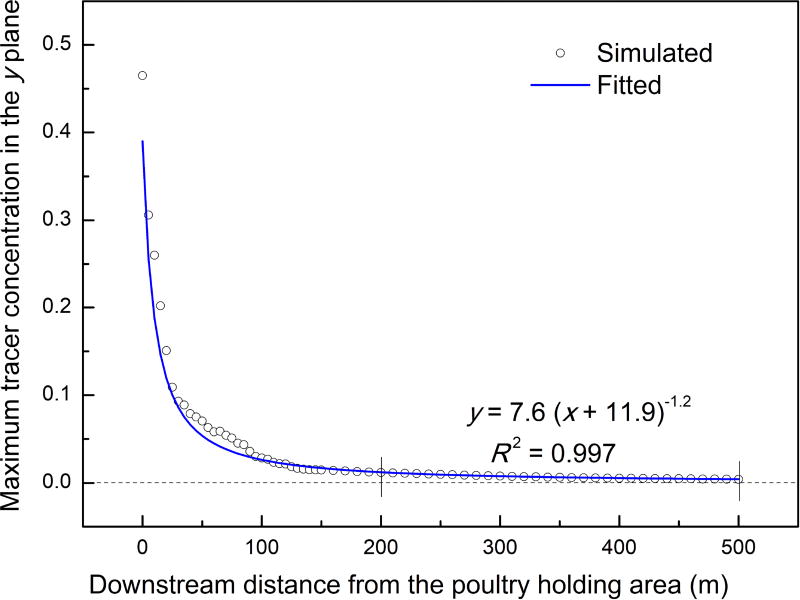

The potential area of AIV downwind spread is a crucial question for infection control during outbreaks. In accordance with EU directive 92/40/EEC, controlling outbreaks of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) viruses relies on movement restrictions for farms within a radius of at least 10 km of an infected farm and culling the infected poultry. Figure 5 shows the tracer concentration decay downstream of the poultry market. In our study, the tracer gas concentration decreased to 0.1 and 0.005 respectively of the source value detected at the live poultry holding area at a downwind distance of 30 m and 440 m. Only data collected beyond 200 m on the downwind side were free from the disturbing effect caused by the surrounding buildings. In our simulation, c ~ x−1.2; the tracer concentration had a slower decay rate compared with that of a point source situation, where c ~ x−2 (Weil and Brower, 1984). For the scenario in Experiment A, if virus deposition by gravity was not taken into consideration, the virus concentration would only drop below 100 copies/m3 after a downwind distance exceeding 5.9 km.

Figure 5.

Modelled tracer concentration decay in the downstream direction for Experiment A. The simulated data was fitted in the range 200–500 m downstream of the poultry holding area.

It is worth nothing that tracer gas was used as a surrogate for virus-laden particles in our simulation, and the particle depositions in the henhouses, around the buildings, or downstream of the henhouses were not considered. In reality, particles over 5 µm in diameter may deposit within a few kilometers. In addition, fluctuations in wind speed and direction in the 30 min sampling period were not considered, which might have resulted in a wider dispersion range of the particles. Further efforts may be made to improve the CFD modelling in the future for a more reliable and robust correlation with the experimental results.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we detected airborne AIV RNA as far as 100 m downwind of the live poultry holding area. The majority of AIV RNA and 18S RNA was detected from particles with a diameter >1 µm, and the highest concentrations were 4.4 × 105 copies/m3 and 2.5 × 108 copies/m3, respectively. Because virus concentration was below the linear range of quantification, 18S RNA was used as an indicator for modeling the spread of avian influenza virus during outbreak conditions.

The CFD model indicated the combined effect of wind and surrounding buildings on the spread of avian influenza virus. Surrounding buildings may potentially enhance the lateral spread or create air circulation that causes the tracer gas to spread against the wind. Close to the poultry market, the virus concentration can be high and the spread pattern is complex; with further distance, the decay rate is proportional to x−1.2.

Table 2. Air sampling results from Experiment B at the wholesale market.

Air sampling was performed on February 24, 2016. The recorded temperature was 13.4 °C, 69% relative humidity, and Northern wind at 3 m/s.

| Sample Point No. |

Concentrations of influenza virus M gene, copies/m3 (influenza subtype detected) |

Concentrations of 18s RNA, copies/m3 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | < 1 µm | 1–4 µm | > 4 µm | |

| 1 | Neg | 3.4 × 104 (H9) | 3.2 × 105 (H9) | 1.6 × 104 | 9.5 × 105 | 7.3 × 106 |

| 2 | Neg | 6.8 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 1.1 × 104 (H9) | 1.4 × 104 | 4.4 × 105 | 3.4 × 106 |

| 3 | Neg | Neg | 5.7 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 4.6 × 104 | 2.8 × 104 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 4 | Neg | 3.7 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 8.7 × 103 (H9) | 1.5 × 104 | 3.5 × 104 | 5.3 × 105 |

| 5 | 5.9 × 103 | 2.8 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 7.2 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 5.3 × 103 | 2.5 × 104 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 6 | Neg | Neg | 2.6 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 1.0 × 104 | 1.3 × 104 | 5.1 × 105 |

| 7 | 1.5 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 2.3 × 104 (H9) | 1.5 × 103 (Non-H5/7/9) | 4.9 × 103 | 4.0 × 104 | 9.7 × 104 |

Highlights.

Airborne transmission potential of avian influenza virus in a poultry market was investigated;

Viral RNA are readily detectable by air sampling, predominantly from particles larger than 1 µm;

CFD modeling reveals the combined effect of wind direction and surrounding buildings;

The virus concentration has a slow decay rate in air in the downwind direction.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. William G. Lindsley for providing the NIOSH bioaerosol samplers. This study was supported by Contract HHSN272201400006C from the NIAID, NIH, the Theme-based Research Scheme (Project No. T11-705/14N) from the Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR, China, and AXA Research Award.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Chen P-S, Lin CK, Tsai FT, Yang C-Y, Lee C-H, Liao Y-S, Yen C-Y, King C-C, Wu J-L, Wang Y-C, Lin K-H. Quantification of Airborne Influenza and Avian Influenza Virus in a Wet Poultry Market using a Filter/Real-time qPCR Method. Aerosol Science and Technology. 2009;43(4):290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. Ventilation performance prediction for buildings: A method overview and recent applications. Building and environment. 2009;44(4):848–858. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Liang W, Yang S, Wu N, Gao H, Sheng J, et al. Human infections with the emerging avian influenza A H7N9 virus from wet market poultry: clinical analysis and characterisation of viral genome. The Lancet. 2013;381(9881):1916–1925. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60903-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Ozaki H, Webby RJ, Webster RG, Peiris JS, Poon L, Butt C, Leung YH, Guan Y. Continuing evolution of H9N2 influenza viruses in Southeastern China. J Virol. 2004;78(16):8609–14. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.16.8609-8614.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling BJ, Jin L, Lau EHY, Liao Q, Wu P, Jiang H, Tsang TK, Zheng J, Fang VJ, Chang Z, Ni MY, zhang Q, Ip DKM, Yu J, Li Y, Wang L, Tu W, Meng L, Wu JT, Luo H, Li Q, Shu Y, Li Z, Feng Z, Yang W, Wang Y, Leung GM, Yu H. Comparative epidemiology of human infections with avian influenza A H7N9 and H5N1 viruses in China: a population-based study of laboratory-confirmed cases. The Lancet. 2013;382(9887):129–137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61171-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber L, Voelker L, Hill G, Rodriguez J. Description of live poultry markets in the United States and factors associated with repeated presence of H5/H7 low-pathogenicity avian influenza virus. Avian Dis. 2007;51(1 Suppl):417–20. doi: 10.1637/7571-033106R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAD. H7N9 situation update. [accessed Jul. 27, 2017];2017 [Google Scholar]

- Jonges M, Van Leuken J, Wouters I, Koch G, Meijer A, Koopmans M. Wind-Mediated Spread of Low-Pathogenic Avian Influenza Virus into the Environment during Outbreaks at Commercial Poultry Farms. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, He J, Song T, Rutherford S, Wu J, Lin J, Huang G, Tan X, Zhong H. Environmental Sampling for Avian Influenza A(H7N9) in Live-Poultry Markets in Guangdong, China. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchipudi SV, Tellabati M, Nelli RK, White GA, Perez BB, Sebastian S, Slomka MJ, Brookes SM, Brown IH, Dunham SP, Chang KC. 18S rRNA is a reliable normalisation gene for real time PCR based on influenza virus infected cells. Virology Journal. 2012;9:230. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-9-230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau EH, Leung YH, Zhang LJ, Cowling BJ, Mak SP, Guan Y, Leung GM, Peiris JS. Effect of interventions on influenza A (H9N2) isolation in Hong Kong's live poultry markets, 1999–2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(9):1340–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1309.061549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ACY. M.Phil. thesis. The University of Hong Kong; 2006. Theoretical Modeling and Experimental Studies of Particle-Laden Plumes from Wastewater Discharges. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley WG, Schmechel D, Chen BT. A two-stage cyclone using microcentrifuge tubes for personal bioaerosol sampling. J of Environ Monit. 2006;8(11):1136–1142. doi: 10.1039/b609083d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley WG, Blachere FM, Thewlis RE, Vishnu A, Davis KA, Cao G, et al. Measurements of airborne influenza virus in aerosol particles from human coughs. PLoSONE. 2010;5:e15100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen DC, Uyeki TM, Jadhao S, Maines T, Shaw M, Matsuoka Y, Smith C, Rowe T, Lu X, Hall H, Xu X, Balish A, Klimov A, Tumpey TM, Swayne DE, Huynh LP, Nghiem HK, Nguyen HH, Hoang LT, Cox NJ, Katz JM. Isolation and Characterization of Avian Influenza Viruses, Including Highly Pathogenic H5N1, from Poultry in Live Bird Markets in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 2001. J Virol. 2005;79(7):4201–12. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.7.4201-4212.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO information for molecular diagnosis of influenza virus. [accessed Jul. 27, 2017];2015

- WHO. Cumulative number of confirmed human cases of avian influenza A(H5N1) reported to WHO. [accessed Jul. 26, 2017];2017

- Peiris JSM, Cowling BJ, Wu JT, Feng L, Guan Y, Yu H, Leung GM. Interventions to reduce zoonotic and pandemic risks from avian influenza in Asia. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016;16(2):252–258. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickler AR, Trampel DW, Roth JA. The onset of virus shedding and clinical signs in chickens infected with high-pathogenicity and low-pathogenicity avian influenza viruses. Avian pathology: journal of the WVPA. 2008;37(6):555–77. doi: 10.1080/03079450802499118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayne DE. Avian influenza. John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Bi Y, Wong G, Gray GC, Gao GF, Li S. Epidemiology, evolution, and recent outbreaks of avian influenza virus in China. Journal of virology. 2015;89(17):8671–8676. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01034-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J, LI Y. Enhanced spread of expiratory droplets by turbulence in a cough jet. Building and Environment. 2015;93:86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Weil JC, Brower RP. An updated Gaussian plume model for tall stacks. Journal of the Air Pollution Control Association. 1984;34(8):818–827. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Shi W, Lin J, Wang M, Chen X, Liu K, Xie Y, Luo L, Anderson BD, Lednicky JA, Gray GC, Lu J, Wang T. Aerosolized Avian Influenza A (H5N6) Virus Isolated from a Live Poultry Market, China. Journal of Infection. 2016;74:89. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wu J, Zeng X, Huang G, Zou L, Song Y, Gopinath D, Zhang X, Kang M, Lin J, Cowling BJ, Lindsley WG, Ke C, Peiris JSM, Yen HL. Isolation of H5N6, H7N9 and H9N2 avian influenza a viruses from air sampled at live poultry markets in China, 2014 and 2015. Eurosurveillance. 2016;21(35) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.35.30331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]