1. Overview

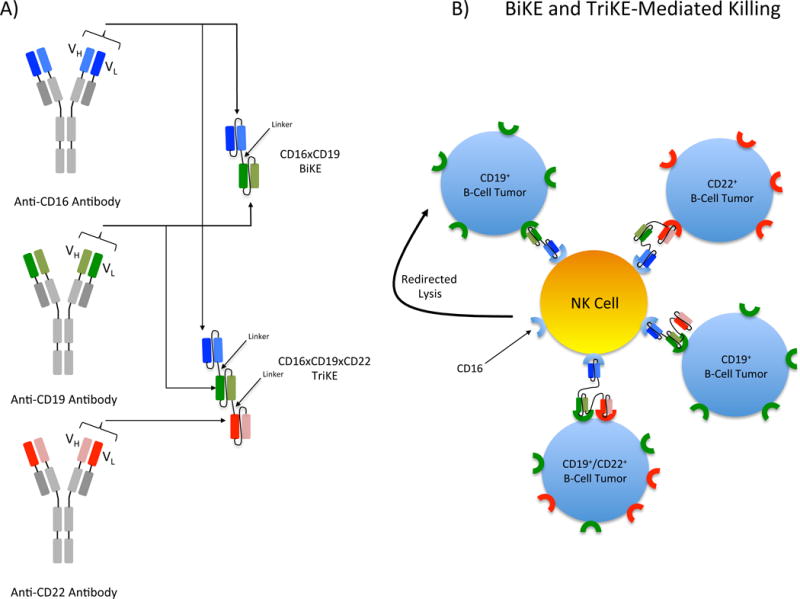

Targeted cancer immunotherapies are currently a subject of great clinical interest and potential [1]. While a great deal of interest has recently been placed upon generation of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) expressing T cells from monoclonal antibodies shown to target human malignancies [2], and more even more recently upon generation of CAR-expressing natural killer (NK) cells [3,4], these approaches require a personalized approach that is expensive, time consuming, and difficult to apply on a large scale. There is a clear need for targeted off-the-shelf therapies that augment the current monoclonal antibody approach. This chapter focuses on generation of bi- and tri-specific killer engagers (BiKEs and TriKEs) meant to target NK cells to the tumor synapse and induce their activation at that site (Figure 1). Unlike full-length bi- and tri-specific antibodies, BiKEs and TriKEs are small molecules containing a single variable portion (VH and VL) of an antibody linked to one (BiKE) or two (TriKE) variable portions from other antibodies of different specificity.

Figure 1.

Structure and function of BiKEs and TriKEs. A) BiKEs and TriKEs are constructed from a single heavy (VH) and light (VL) chain of the variable region of each antibody of interest. VH and VL domains are joined by a short flexible polypeptide linker to prevent dissociation. Shown here is a BiKE constructed from the variable regions of anti-CD16 and anti-CD19 and a TriKE constructed from the variable regions of anti-CD16, anti-CD19 and anti-CD22. B) BiKE and TriKE binding to NK cells and their targets result in the formation of an immunological synapse and triggers NK killing of the target cell through activation of the low affinity Fc receptor, CD16, on NK cells. The CD16×CD19×CD22 TriKE can recognize targets expressing CD19 (green receptors), CD22 (red receptors) or both receptors simultaneously allowing for more versatile target recognition than the CD16×CD19 BiKE.

NK cells are ideal candidates for immune cell-targeted therapies because they do not require prior sensitization to lyse tumor targets and to release proinflammatory cytokines, are not HLA-restricted, and can mediate graft-versus-leukemia (or tumor) without inducing graft-versus-host disease [5,6]. Although NK cells possess a variety of activating receptors and can mediate function in several different ways, their role in antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) is of particular relevance in this chapter. ADCC is mediated by CD16 (FcγRIII), the low affinity receptor for IgG Fc [7]. Two isoforms of CD16 exist in humans, CD16A and CD16B [8]. CD16A is expressed in NK cells, macrophages, and placental trophoblasts as a polypeptide-anchored transmembrane protein while CD16B is expressed in neutrophils in a GPI-anchored form [9–12]. Although the extracellular portion of CD16A and CD16B share a high level of homology (95-97%), CD16A can trigger killing of tumor targets and IL-2 production while CD16B cannot [9,13–15].

In human NK cells, CD16 is mostly expressed in the CD56dim subset, although populations of CD56bright CD16+ NK cells have been observed after transplant [16,17]. Engagement of CD16 through encounter with the Fc portion of antibodies or direct crosslinking by anti-CD16 antibody results in signals through the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) of the associated FcεRIγ and CD3ζ chain subunits, leading to cytokine and cytotoxic responses [18–20]. Unlike other activating receptors present in human NK cells, CD16 can robustly mediate activation without the need for co-engagement of other receptors [21]. These signaling properties allow for NK CD16-mediated targeting of antibody-coated cells in natural settings of viral infection, autoimmunity and the onset of some forms of tumors [22–24]. The latter has been exploited in the clinic by generating monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting specific tumor antigens to drive ADCC against those tumors [25–29].

Driving ADCC through mAbs has resulted in significant clinical success. Specific targeting of tumors with BiKEs and TriKEs has the potential to build upon this success and improve efficacy. Binding affinity appears to be an important component of ADCC. This impression is supported by increased rituximab-driven cytotoxicity of B cell tumors mediated by NK cells containing the CD16A-158VV or VF allotypes which, when compared to the CD16A-158FF allotype, display decreased affinity for the Fc portions of antibodies [30]. Therefore, BiKEs and TriKEs might improve NK cell function by generating a stronger interaction through binding with anti-CD16 than that produced by binding of CD16 to the natural Fc portion of antibodies. This increase in affinity and cytotoxicity was demonstrated in a study comparing natural binding of CD16 to the Fc portion of an anti-HER2 antibody versus binding of CD16 through an anti-HER2 × anti-CD16 bi-specific antibody. Data showed a 3.4 fold increase in affinity in the bi-specific antibody versus binding of the native anti-HER2 Fc [31]. The efficacy of therapeutic mAbs in vivo, in contrast to their high ADCC efficacy in vitro, is further attenuated by the presence of physiologic serum IgG levels in plasma. In the in vivo setting, ADCC potency is diminished by saturation of CD16 receptors, thus competing for binding with the therapeutic mAb [32]. Such competition for binding of the therapeutic Fc portion of antibodies requires high serum levels of the mAb to be sustained over several months of treatment in order to achieve in vivo efficacy [33,34]. BiKEs and TriKEs bypass this obstacle by binding the CD16 receptor directly. An additional benefit that BiKEs and TriKEs may have over mAbs is superior biodistribution as a consequence of their smaller size, particularly in the treatment of solid tumors [35–37]. In addition to these advantages, BiKEs and TriKEs are non-immunogenic, have quick clearance properties and can be engineered quickly to target known tumor antigens. These attributes make them an ideal pharmaceutical platform for potentiated NK cell-based immunotherapies.

Over the past two decades multivalent antibodies, and more recently BiKEs and TriKEs, have been used to target tumor antigens and CD16 on NK cells [38]. While approaches for assembly of multivalent antibodies and the current methodology for BiKE and TriKE engineering has evolved, the function of these reagents remains unchanged. Bi-specific and Tri-specific reagents have been generated to engage CD16 on the NK cell and the following tumor antigens: CD20 and CD19 on B cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [39–47], CD19 and CD33 on mixed lineage leukemia [48], CD33 or CD33 and CD123 on acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) [49–51], HLA Class II on lymphoma [52], CD30 on Hodgkin’s disease [53–62], EGF-R on EGF-R+ tumors [63,64], HER2/neu on metastatic breast cancer and other HER2 expressing tumors [31,65–71], and MOV19 on ovarian cancer [72]. Our group has contributed to the field through generation and testing of BiKEs and TriKEs that target CD16 and CD19/CD22 on B cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [73], CD33 on AML [74] and MDS/MDSCs [75], and EpCAM on prostate, breast, colon, head, and neck carcinomas [76]. Activation through the BiKEs and TriKEs elicited potent cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. In the case of the CD16×CD19×CD22 TriKE, the CD107a response to primary CLL and ALL exceeded that of rituximab. The CD16×CD33 BiKE was capable of overcoming HLA-mediated inhibition with primary refractory AML blasts and restored function of NK cells from MDS patients. Encouraged by their translational potential, we are currently producing some versions of these reagents for clinical use. Basic reagent production methods are described in the next section.

2. Methodology

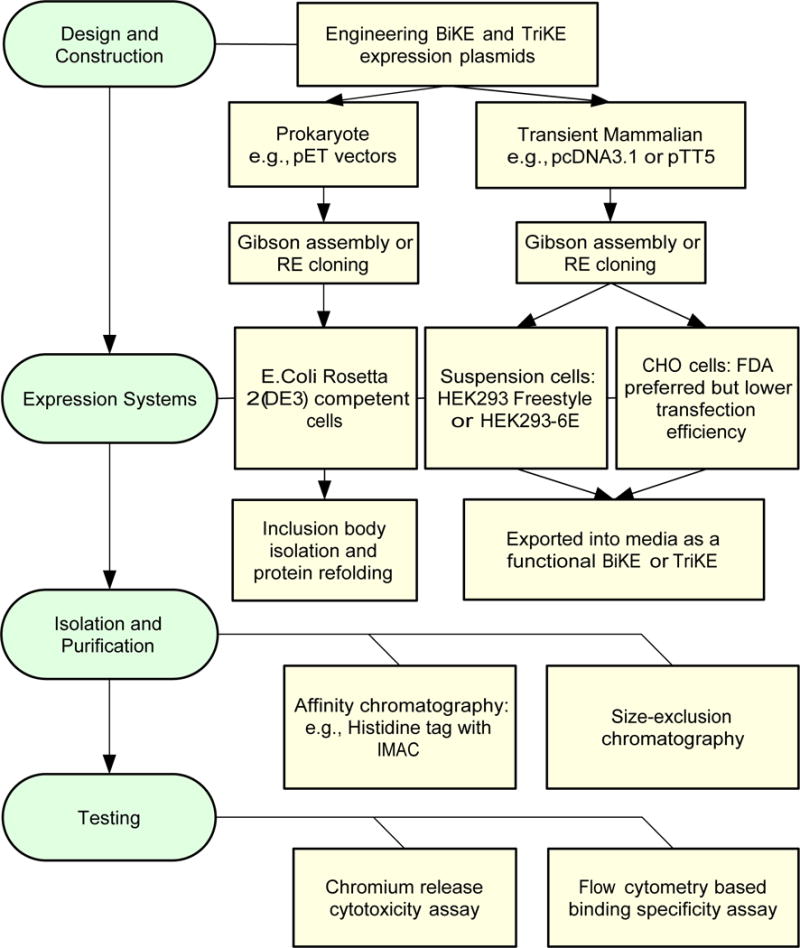

BiKE design is a complex process. This section provides an overview of the entire methodology (summarized in Figure 2). Once a target of interest has been defined, the first step in the design of BiKEs requires selection of a source for the variable fragments. Sequences for relevant fragments can be obtained from published work, hybridomas, B cells from immunized animals, phage display and other such display technology. For bacterial expression systems, phage display is ideal because the constructs are selected in bacteria, essentially pre-screening their function in the system of expression. The next step involves selection of a proper linker. BiKEs combine two different antigen-binding sites with a short flexible linker. The antigen-binding domains are single-chain variable fragments (scFv), which consist of heavy and light variable domains, also fused with a flexible linker (VH-linker-VL) [35]. The main linker design is important to the function of the BiKE by allowing separation of the functional domains as well as providing flexibility to bind the two (or three in the case of the TriKE) epitopes on the different targeted cells [77]. The (SGGG)4 linker is one of the first flexible linkers used in the construction of single-chain variable fragments (scFv) [78]. Another commonly used linker, the 218s linker (GSTSGSGKPGSGEGSTKG), is reported to improve proteolytic stability and reduce aggregation [79]. To reduce immunogenicity, our group utilized an HMA linker (PSGQAGAAASESLFVSNHAY) between the antiCD16 and the tumor antigen scFv [76].

Figure 2.

Workflow for generation of BiKEs and TriKEs. In the left (green) are the four steps necessary for generation and validation of the BiKE/TriKE constructs. In the right (yellow) are possible options for each of the steps. CHO: Chinese hamster ovary cells. IMAC: immobilized metal affinity chromatography. RE: restriction enzyme.

Once the components of the BiKE have been determined, selection of an appropriate vector for expression follows. We and other investigators focus on plasmid expression systems in bacteria and mammalian cells to create BiKEs, but there are other less utilized expression systems, such as lentivirus or sleeping beauty, which will not be discussed in this section. For bacterial expression systems, the pET vector is the system most commonly used in conjunction with the Rosetta 2(DE3) host cells (Novagen). The Rosetta 2(DE3) cells contain an IPTG- inducible T7 RNA polymerase, which is compatible with the pET vectors. Another feature of this strain is that it has been engineered to express a “universe” set of transfer RNAs as a way to mitigate the need for codon optimization. For transient mammalian expression systems, the pTT5 vector can be utilized in conjunction with the HEK293-E6 suspension cells or the pcDNA3.1 system can be used with the HEK293 Freestyle cells (Invitrogen). Reported yields have been higher in the HEK293-E6 system [80]. These cells express a truncated variant of the Epstein Barr virus (EBV) for which pTT5 vector contains the short EBV oriP for episomal replication. These two systems display advantages in yields and ease of use but a number of other systems utilizing different vectors can also be applied [80,81].

Upon selection of a vector, one can begin cloning the BiKE components into the vector backbone. Significant advances have been made in the recombination technique. While there are several ways to clone DNA fragments into the vector backbone, we and others favor Gibson assembly because it is cost and time efficient [82]. Gibson assembly utilizes in vitro homologous recombination through insertion of a DNA fragment into a vector, where insertion is directed by homologous regions that are present at the end of the insert DNA and the linearized vector DNA [83]. An advantage of Gibson assembly over standard restriction cloning is that it requires little to no restriction enzyme utilization and multiple pieces can be cloned in one reaction. With the advent of this method, together with recent access to inexpensive high-fidelity synthetic DNA, it is now possible to construct BiKE expression plasmids in a few days of labor.

Following preparation, the BiKE expression vector can then be chemically transduced into E. coli or transfected into mammalian cells through lipid or chemical means and, to a lesser extent, through electroporation. The advantage of E. coli versus the mammalian system is that it allows for quick, easy, robust and inexpensive expression of the BiKEs [84]. An important difference between the bacterial and mammalian systems is that in the mammalian system, fully functional proteins are secreted and can be harvested from the supernatant. A disadvantage of bacteria is that most recombinant proteins are found in an insoluble form, termed an inclusion bodies [85]. To resolve this problem, lysis of the bacteria and isolation of the inclusion bodies through centrifugation followed by solubilization with strong denaturing reagents is required. The protein then must be refolded. Refolding is carried out at low protein concentrations. Conditions for refolding of the recombinant protein must be optimized (i.e.: pH, ionic strength, temperature, and redox environment). The protein can then be isolated through size exclusion chromatography or through the use of an affinity tag, such as histidine-tags [85,86]. As discussed, both systems have advantages and disadvantages. While the bacterial system is quick, easy, and robust, the mammalian system does not require re-folding and can be utilized to generate smaller amounts of functional protein quickly for initial screening. Another consideration possibly favoring the mammalian approach is that most therapeutic recombinant proteins gaining FDA approval are made in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells [87].

Flow cytometry is used to evaluate binding of the constructs to their respective targets. Prior to incorporation into the full bi- or tri-specific constructs containing the anti-CD16 variable portion and the linker/s, individual variable portions containing a His-tag or similar small tag are incubated with cells expressing the antigen of interest or cells expressing an irrelevant antigen, to evaluate non-specific binding. A biotinylated anti-His antibody is then used to recognize the His-tag on the variable portion, followed by addition of fluorescently labeled streptavidin to attain fluorescent conjugation. To ensure that the variable fragment is binding to the desired antigen, binding is then compared to fluorescently labeled commercial antibodies to the antigen of choice. Alternatively, the variable portion can be biotinylated or fluorescently labeled directly. However, this approach may increase risk of altering binding to the antigen. If the variable construct is designed from a known antibody for which fluorescently labeled forms already exist, the construct can be tested in a competition assay. In such assays, increasing concentrations of construct are bound to the cells expressing the specific antigen prior to addition of the known fluorescently labeled antibody. Specific binding is then measured by a decrease in binding of the fluorescently labeled full antibody form, indicating binding of the variable fragment to the antigen.

Once specific binding has been confirmed, the variable portion is incorporated into a full BiKE or TriKE construct and the functional activity of the construct is evaluated by two different methods. First, the ability of NK cells to degranulate in response to targets coated in the construct is assessed by a redirected lysis assay. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or purified NK cells are co-cultured with targets at a range of effector to target (E:T) ratios (1:1 to 20:1) in the presence or absence of a saturating concentration of the BiKE/TriKE of interest. Higher ratios are required for PMBCs when compared to purified NK cells. Effectors, targets, and constructs are incubated together for several hours (usually 5) and then surface LAMP-1 (CD107a), used to evaluate degranulation, and intracellular IFN-γ and TNF-α, used to evaluate cytokine secretion, are assessed on the NK cells by flow cytometry. Irrelevant targets are used as a negative control in this assay, while full length antibodies that direct ADCC towards the antigen of choice are used as a positive/comparative control. While this assay determines the level to which NK cells are activated, it does not reflect the level of target cell killing in response to the NK cell activation. To evaluate target cell killing a cytotoxicity assay, such as a chromium release assay, is performed. In this assay, target cells are labeled with radioactive Chromium-51 (51 Cr) prior to co-culture with PBMCs or purified NK cells and the BiKE/TriKE. E:T ratios in this assay range from 20:1 to 0.625:1. Wells containing targets without NK cells are plated for use as maximum (10% SDS mediated lysis) and minimum (no treatment) release groups. These groups are used for the calculation of percent targets killed. During the incubation, as target cells are killed they release 51 Cr into the supernatant while the targets that remain alive keep the 51Cr sequestered inside the cell. 51Cr release is then assessed on a gamma counter and the percent of targets killed is calculated. Controls similar to those mentioned in the flow-based assay are also included. Once the specificity and efficacy of the BiKEs/TriKEs has been determined, the constructs can now be tested with clinical samples and/or in more complex in vivo killing assays utilizing NSG mice, engrafted xenogeneic tumors, and transferred human NK cells.

3. Future Directions

Although current BiKE and TriKE constructs display great translational potential, efforts are currently underway to further improve their efficacy. One obstacle that could limit the efficacy of BiKEs and TriKEs, as well as all other antibody therapy mediated through NK cells, is CD16 expression. NK cell-mediated ADCC by therapeutic antibodies depends on ligation of CD16, on the NK cell, with the Fc portion of the antibody [88]. BiKEs and TriKEs, as well as other formats of bi- and tri-specific antibodies, mediate redirected lysis of the target and NK cell function through direct binding and crosslinking of the CD16 receptor. This bears relevance because CD16 is rapidly clipped from the surface of NK cells activated through CD16 by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), in particular ADAM-17 [89–92]. Activation through cytokines can also result in the clipping of CD16 [93]. Loss of surface CD16 expression on activated NK likely results in a diminished capacity to mediate subsequent rounds of ADCC. To address this concern, we and others are currently evaluating MMP-specific inhibitors as a means to prevent CD16 clipping during NK cell activation [94,95]. We have demonstrated that inhibition of ADAM-17 results in superior function post CD16 crosslinking and can potentiate rituximab-mediated responses in vitro. We have also shown that ADAM-17 inhibition can enhance BiKE mediated killing against myeloid targets in vitro [74]. These results indicate that co-treatment with ADAM-17 inhibitor may be a good strategy to enhance BiKE/TriKE function in the clinic.

A different approach to circumvent the CD16 problem is to target other receptors on the NK cells with the BiKEs and TriKEs. CD16 was originally selected owing to its ability to potently activate NK cells and overcome inhibitory signaling [21]. This was highlighted in the BiKE system showing that the CD16×CD33 BiKE could overcome HLA-mediated inhibition in primary AML blasts and could restore NK cell function from MDS patients, whose natural cytotoxicity is thought to be impaired [74,75]. However, co-engagement of other receptors, particularly NKG2D and 2B4, has been shown to induce activation similar to that provided by CD16 alone [21]. There is also potential for TriKEs engaging CD16, a tumor antigen, and another NK cell activating or co-stimulatory receptor. For instance, co-engagement of CD16 with DNAM-1, CD2, or 2B4 was shown to potentiate function in NK cells from MDS patients [75]. Co-administration of cytokines may also enhance BiKE mediated NK cell function. Several cytokines, including IL-15, IL-2, IL-21, and IL-12 have prominent roles in NK cell development, proliferation, survival, and/or activation. Encouraged by these attributes, trials are underway to implement them in the clinic [96]. Besides the aforementioned attributes, some of these cytokines have been shown to also potentiate ADCC, making them an interesting co-therapeutic approach.

While personalized CAR-T cell therapies have recently enjoyed a great deal of clinical success [2], there remains a clear need for off-the shelf reagents that enhance targeting of the immune system to tumor antigens. Directing targeting of NK cells is a compelling therapeutic approach on the basis of their ability to quickly kill tumors and secrete cytokines without prior priming [5]. BiKEs and TriKEs are an important conduit for achieving this since they are relatively easy to produce, drive potent NK cell activation through CD16 crosslinking, and can be utilized to target almost any tumor antigen for which an antibody has been designed. This is true regardless of whether the antibody displays activating properties because the activation is driven through the CD16 scFv. To date our group has primarily focused on Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (through CD19 and CD22), AML and MDS (through CD33), and breast, colon, and lung carcinomas (through EpCAM) [73–76]. Notably, there are an abundance of promising tumor antigens for which therapeutic antibodies have been designed that could be incorporated into BiKE and TriKE platforms [37]. These include CD30 (Hodgkin’s lymphoma), CD52 (CLL), CEA (breast, colon, and lung), gpA33 (colorectal), CAIX (renal cell), Mucins (breast, colon, lung, and ovarian), PSMA (prostate), VEGFR (epithelium-derived solid tumors), VEGF and Integrins αVβ3 and α5β1 (tumor vasculature), EGFR (breast, lung, colon, glioma, and head and neck), and ERBB2 and ERBB3 (breast, lung, colon, ovarian, and prostate). This list, by no means comprehensive, enumerates several important hematological and solid tumors that potentially could be targeted through the powerful BiKE platform.

References

- 1.Masters GA, Krilov L, Bailey HH, Brose MS, Burstein H, Diller LR, Dizon DS, Fine HA, Kalemkerian GP, Moasser M, Neuss MN, O’Day SJ, Odenike O, Ryan CJ, Schilsky RL, Schwartz GK, Venook AP, Wong SL, Patel JD. Clinical cancer advances 2015: Annual report on progress against cancer from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(7):786–809. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.9746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caruana I, Diaconu I, Dotti G. From monoclonal antibodies to chimeric antigen receptors for the treatment of human malignancies. Semin Oncol. 2014;41(5):661–666. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermanson DL, Kaufman DS. Utilizing chimeric antigen receptors to direct natural killer cell activity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:195. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glienke W, Esser R, Priesner C, Suerth JD, Schambach A, Wels WS, Grez M, Kloess S, Arseniev L, Koehl U. Advantages and applications of CAR-expressing natural killer cells. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:21. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2015.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vivier E, Raulet DH, Moretta A, Caligiuri MA, Zitvogel L, Lanier LL, Yokoyama WM, Ugolini S. Innate or adaptive immunity? The example of natural killer cells. Science. 2011;331(6013):44–49. doi: 10.1126/science.1198687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velardi A. Natural killer cell alloreactivity 10 years later. Curr Opin Hematol. 2012;19(6):421–426. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3283590395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anegon I, Cuturi MC, Trinchieri G, Perussia B. Interaction of Fc receptor (CD16) ligands induces transcription of interleukin 2 receptor (CD25) and lymphokine genes and expression of their products in human natural killer cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1988;167(2):452–472. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annual review of immunology. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvaraj P, Carpen O, Hibbs ML, Springer TA. Natural killer cell and granulocyte Fc gamma receptor III (CD16) differ in membrane anchor and signal transduction. J Immunol. 1989;143(10):3283–3288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perussia B, Ravetch JV. Fc gamma RIII (CD16) on human macrophages is a functional product of the Fc gamma RIII-2 gene. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21(2):425–429. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klaassen RJ, Ouwehand WH, Huizinga TW, Engelfriet CP, von dem Borne AE. The Fc-receptor III of cultured human monocytes. Structural similarity with FcRIII of natural killer cells and role in the extracellular lysis of sensitized erythrocytes. J Immunol. 1990;144(2):599–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishikiori N, Koyama M, Kikuchi T, Kimura T, Ozaki M, Harada S, Saji F, Tanizawa O. Membrane-spanning Fc gamma receptor III isoform expressed on human placental trophoblasts. Am J Reprod Immunol. 1993;29(1):17–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.1993.tb00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravetch JV, Perussia B. Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII(CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1989;170(2):481–497. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanier LL, Ruitenberg JJ, Phillips JH. Functional and biochemical analysis of CD16 antigen on natural killer cells and granulocytes. J Immunol. 1988;141(10):3478–3485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirthmueller U, Kurosaki T, Murakami MS, Ravetch JV. Signal transduction by Fc gamma RIII (CD16) is mediated through the gamma chain. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1992;175(5):1381–1390. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper MA, Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. The biology of human natural killer-cell subsets. Trends in immunology. 2001;22(11):633–640. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beziat V, Duffy D, Quoc SN, Le Garff-Tavernier M, Decocq J, Combadiere B, Debre P, Vieillard V. CD56brightCD16+ NK cells: a functional intermediate stage of NK cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;186(12):6753–6761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vivier E, Nunes JA, Vely F. Natural killer cell signaling pathways. Science. 2004;306(5701):1517–1519. doi: 10.1126/science.1103478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vivier E, Morin P, O’Brien C, Druker B, Schlossman SF, Anderson P. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Fc gamma RIII(CD16): zeta complex in human natural killer cells. Induction by antibody-dependent cytotoxicity but not by natural killing. J Immunol. 1991;146(1):206–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Fcgamma receptors as regulators of immune responses. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8(1):34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bryceson YT, Ljunggren HG, Long EO. Minimal requirement for induction of natural cytotoxicity and intersection of activation signals by inhibitory receptors. Blood. 2009;114(13):2657–2666. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-01-201632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shore SL, Nahmias AJ, Starr SE, Wood PA, McFarlin DE. Detection of cell-dependent cytotoxic antibody to cells infected with herpes simplex virus. Nature. 1974;251(5473):350–352. doi: 10.1038/251350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laszlo A, Petri I, IIyes M. Antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)-reaction and an in vitro steroid sensitivity test of peripheral lymphocytes in children with malignant haematological and autoimmune diseases. Acta paediatrica Hungarica. 1986;27(1):23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Natsume A, Niwa R, Satoh M. Improving effector functions of antibodies for cancer treatment: Enhancing ADCC and CDC. Drug design, development and therapy. 2009;3:7–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Albertini MR, Hank JA, Sondel PM. Native and genetically engineered anti-disialoganglioside monoclonal antibody treatment of melanoma. Cancer chemotherapy and biological response modifiers. 2005;22:789–797. doi: 10.1016/s0921-4410(04)22037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garcia-Foncillas J, Diaz-Rubio E. Progress in metastatic colorectal cancer: growing role of cetuximab to optimize clinical outcome. Clinical & translational oncology: official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico. 2010;12(8):533–542. doi: 10.1007/s12094-010-0551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garnock-Jones KP, Keating GM, Scott LJ. Trastuzumab: A review of its use as adjuvant treatment in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive early breast cancer. Drugs. 2010;70(2):215–239. doi: 10.2165/11203700-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navid F, Santana VM, Barfield RC. Anti-GD2 antibody therapy for GD2-expressing tumors. Current cancer drug targets. 2010;10(2):200–209. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winter MC, Hancock BW. Ten years of rituximab in NHL. Expert opinion on drug safety. 2009;8(2):223–235. doi: 10.1517/14740330902750114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Congy-Jolivet N, Bolzec A, Ternant D, Ohresser M, Watier H, Thibault G. Fc gamma RIIIa expression is not increased on natural killer cells expressing the Fc gamma RIIIa-158V allotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68(4):976–980. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore GL, Bautista C, Pong E, Nguyen DH, Jacinto J, Eivazi A, Muchhal US, Karki S, Chu SY, Lazar GA. A novel bispecific antibody format enables simultaneous bivalent and monovalent co-engagement of distinct target antigens. MAbs. 2011;3(6):546–557. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.6.18123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Preithner S, Elm S, Lippold S, Locher M, Wolf A, da Silva AJ, Baeuerle PA, Prang NS. High concentrations of therapeutic IgG1 antibodies are needed to compensate for inhibition of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity by excess endogenous immunoglobulin G. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(8):1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baselga J, Albanell J. Mechanism of action of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 1):S35–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_1.s35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berinstein NL, Grillo-Lopez AJ, White CA, Bence-Bruckler I, Maloney D, Czuczman M, Green D, Rosenberg J, McLaughlin P, Shen D. Association of serum Rituximab (IDEC-C2B8) concentration and anti-tumor response in the treatment of recurrent low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1998;9(9):995–1001. doi: 10.1023/A:1008416911099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holliger P, Hudson PJ. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(9):1126–1136. doi: 10.1038/nbt1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157(2):220–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott AM, Wolchok JD, Old LJ. Antibody therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(4):278–287. doi: 10.1038/nrc3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrini S, Cambiaggi A, Cantoni C, Canevari S, Mezzanzanica D, Colnaghi MI, Moretta L. Targeting of T or NK lymphocytes against tumor cells by bispecific monoclonal antibodies: role of different triggering molecules. International journal of cancer Supplement = Journal international du cancer Supplement. 1992;7:15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glorius P, Baerenwaldt A, Kellner C, Staudinger M, Dechant M, Stauch M, Beurskens FJ, Parren PW, Winkel JG, Valerius T, Humpe A, Repp R, Gramatzki M, Nimmerjahn F, Peipp M. The novel tribody [(CD20)(2)×CD16] efficiently triggers effector cell-mediated lysis of malignant B cells. Leukemia. 2013;27(1):190–201. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kipriyanov SM, Cochlovius B, Schafer HJ, Moldenhauer G, Bahre A, Le Gall F, Knackmuss S, Little M. Synergistic antitumor effect of bispecific CD19 × CD3 and CD19 × CD16 diabodies in a preclinical model of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Immunol. 2002;169(1):137–144. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kellner C, Bruenke J, Stieglmaier J, Schwemmlein M, Schwenkert M, Singer H, Mentz K, Peipp M, Lang P, Oduncu F, Stockmeyer B, Fey GH. A novel CD19-directed recombinant bispecific antibody derivative with enhanced immune effector functions for human leukemic cells. J Immunother. 2008;31(9):871–884. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318186c8b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kellner C, Bruenke J, Horner H, Schubert J, Schwenkert M, Mentz K, Barbin K, Stein C, Peipp M, Stockmeyer B, Fey GH. Heterodimeric bispecific antibody-derivatives against CD19 and CD16 induce effective antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against B-lymphoid tumor cells. Cancer letters. 2011;303(2):128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Portner LM, Schonberg K, Hejazi M, Brunnert D, Neumann F, Galonska L, Reusch U, Little M, Haas R, Uhrberg M. T and NK cells of B cell NHL patients exert cytotoxicity against lymphoma cells following binding of bispecific tetravalent antibody CD19 × CD3 or CD19 × CD16. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 2012;61(10):1869–1875. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1339-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruenke J, Barbin K, Kunert S, Lang P, Pfeiffer M, Stieglmaier K, Niethammer D, Stockmeyer B, Peipp M, Repp R, Valerius T, Fey GH. Effective lysis of lymphoma cells with a stabilised bispecific single-chain Fv antibody against CD19 and FcgammaRIII (CD16) British journal of haematology. 2005;130(2):218–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson S, Burke S, Huang L, Gorlatov S, Li H, Wang W, Zhang W, Tuaillon N, Rainey J, Barat B, Yang Y, Jin L, Ciccarone V, Moore PA, Koenig S, Bonvini E. Effector cell recruitment with novel Fv-based dual-affinity re-targeting protein leads to potent tumor cytolysis and in vivo B-cell depletion. J Mol Biol. 2010;399(3):436–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schlenzka J, Moehler TM, Kipriyanov SM, Kornacker M, Benner A, Bahre A, Stassar MJ, Schafer HJ, Little M, Goldschmidt H, Cochlovius B. Combined effect of recombinant CD19 × CD16 diabody and thalidomide in a preclinical model of human B cell lymphoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15(9):915–919. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200410000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schubert I, Kellner C, Stein C, Kugler M, Schwenkert M, Saul D, Stockmeyer B, Berens C, Oduncu FS, Mackensen A, Fey GH. A recombinant triplebody with specificity for CD19 and HLA-DR mediates preferential binding to antigen double-positive cells by dual-targeting. MAbs. 2012;4(1):45–56. doi: 10.4161/mabs.4.1.18498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schubert I, Kellner C, Stein C, Kugler M, Schwenkert M, Saul D, Mentz K, Singer H, Stockmeyer B, Hillen W, Mackensen A, Fey GH. A single-chain triplebody with specificity for CD19 and CD33 mediates effective lysis of mixed lineage leukemia cells by dual targeting. MAbs. 2011;3(1):21–30. doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.1.14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Silla LM, Chen J, Zhong RK, Whiteside TL, Ball ED. Potentiation of lysis of leukaemia cells by a bispecific antibody to CD33 and CD16 (Fc gamma RIII) expressed by human natural killer (NK) cells. British journal of haematology. 1995;89(4):712–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb08406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer H, Kellner C, Lanig H, Aigner M, Stockmeyer B, Oduncu F, Schwemmlein M, Stein C, Mentz K, Mackensen A, Fey GH. Effective elimination of acute myeloid leukemic cells by recombinant bispecific antibody derivatives directed against CD33 and CD16. J Immunother. 2010;33(6):599–608. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181dda225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kugler M, Stein C, Kellner C, Mentz K, Saul D, Schwenkert M, Schubert I, Singer H, Oduncu F, Stockmeyer B, Mackensen A, Fey GH. A recombinant trispecific single-chain Fv derivative directed against CD123 and CD33 mediates effective elimination of acute myeloid leukaemia cells by dual targeting. British journal of haematology. 2010;150(5):574–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruenke J, Fischer B, Barbin K, Schreiter K, Wachter Y, Mahr K, Titgemeyer F, Niederweis M, Peipp M, Zunino SJ, Repp R, Valerius T, Fey GH. A recombinant bispecific single-chain Fv antibody against HLA class II and FcgammaRIII (CD16) triggers effective lysis of lymphoma cells. British journal of haematology. 2004;125(2):167–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hombach A, Jung W, Pohl C, Renner C, Sahin U, Schmits R, Wolf J, Kapp U, Diehl V, Pfreundschuh M. A CD16/CD30 bispecific monoclonal antibody induces lysis of Hodgkin’s cells by unstimulated natural killer cells in vitro and in vivo. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 1993;55(5):830–836. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910550523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Renner C, Pfreundschuh M. Treatment of heterotransplanted Hodgkin’s tumors in SCID mice by a combination of human NK or T cells and bispecific antibodies. Journal of hematotherapy. 1995;4(5):447–451. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahin U, Kraft-Bauer S, Ohnesorge S, Pfreundschuh M, Renner C. Interleukin-12 increases bispecific-antibody-mediated natural killer cell cytotoxicity against human tumors. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 1996;42(1):9–14. doi: 10.1007/s002620050245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Renner C, Hartmann F, Pfreundschuh M. Treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease with an anti-CD16/CD30 bispecific antibody. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 1997;45(3–4):184–186. doi: 10.1007/s002620050428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hartmann F, Renner C, Jung W, Deisting C, Juwana M, Eichentopf B, Kloft M, Pfreundschuh M. Treatment of refractory Hodgkin’s disease with an anti-CD16/CD30 bispecific antibody. Blood. 1997;89(6):2042–2047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartmann F, Renner C, Jung W, Pfreundschuh M. Anti-CD16/CD30 bispecific antibodies as possible treatment for refractory Hodgkin’s disease. Leukemia & lymphoma. 1998;31(3–4):385–392. doi: 10.3109/10428199809059232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.da Costa L, Renner C, Hartmann F, Pfreundschuh M. Immune recruitment by bispecific antibodies for the treatment of Hodgkin disease. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2000;46(Suppl):S33–36. doi: 10.1007/pl00014047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Renner C, Hartmann F, Jung W, Deisting C, Juwana M, Pfreundschuh M. Initiation of humoral and cellular immune responses in patients with refractory Hodgkin’s disease by treatment with an anti-CD16/CD30 bispecific antibody. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 2000;49(3):173–180. doi: 10.1007/s002620050617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reiners KS, Kessler J, Sauer M, Rothe A, Hansen HP, Reusch U, Hucke C, Kohl U, Durkop H, Engert A, von Strandmann EP. Rescue of impaired NK cell activity in hodgkin lymphoma with bispecific antibodies in vitro and in patients. Mol Ther. 2013;21(4):895–903. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arndt MA, Krauss J, Kipriyanov SM, Pfreundschuh M, Little M. A bispecific diabody that mediates natural killer cell cytotoxicity against xenotransplantated human Hodgkin’s tumors. Blood. 1999;94(8):2562–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ferrini S, Cambiaggi A, Sforzini S, Canevari S, Mezzanzanica D, Colnaghi MI, Moretta L. Use of anti-CD3 and anti-CD16 bispecific monoclonal antibodies for the targeting of T and NK cells against tumor cells. Cancer detection and prevention. 1993;17(2):295–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elsasser D, Stadick H, Stark S, Van de Winkel JG, Gramatzki M, Schrott KM, Valerius T, Schafhauser W. Preclinical studies combining bispecific antibodies with cytokine-stimulated effector cells for immunotherapy of renal cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1999;19(2C):1525–1528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weiner LM, Clark JI, Davey M, Li WS, Garcia de Palazzo I, Ring DB, Alpaugh RK. Phase I trial of 2B1, a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting c-erbB-2 and Fc gamma RIII. Cancer Res. 1995;55(20):4586–4593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Weiner LM, Clark JI, Ring DB, Alpaugh RK. Clinical development of 2B1, a bispecific murine monoclonal antibody targeting c-erbB-2 and Fc gamma RIII. Journal of hematotherapy. 1995;4(5):453–456. doi: 10.1089/scd.1.1995.4.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shahied LS, Tang Y, Alpaugh RK, Somer R, Greenspon D, Weiner LM. Bispecific minibodies targeting HER2/neu and CD16 exhibit improved tumor lysis when placed in a divalent tumor antigen binding format. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279(52):53907–53914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407888200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xie Z, Shi M, Feng J, Yu M, Sun Y, Shen B, Guo N. A trivalent anti-erbB2/anti-CD16 bispecific antibody retargeting NK cells against human breast cancer cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;311(2):307–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stockmeyer B, Valerius T, Repp R, Heijnen IA, Buhring HJ, Deo YM, Kalden JR, Gramatzki M, van de Winkel JG. Preclinical studies with Fc(gamma)R bispecific antibodies and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor-primed neutrophils as effector cells against HER-2/neu overexpressing breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1997;57(4):696–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weiner LM, Holmes M, Adams GP, LaCreta F, Watts P, Garcia de Palazzo I. A human tumor xenograft model of therapy with a bispecific monoclonal antibody targeting c-erbB-2 and CD16. Cancer Res. 1993;53(1):94–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Weiner LM, Holmes M, Richeson A, Godwin A, Adams GP, Hsieh-Ma ST, Ring DB, Alpaugh RK. Binding and cytotoxicity characteristics of the bispecific murine monoclonal antibody 2B1. J Immunol. 1993;151(5):2877–2886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ferrini S, Prigione I, Miotti S, Ciccone E, Cantoni C, Chen Q, Colnaghi MI, Moretta L. Bispecific monoclonal antibodies directed to CD16 and to a tumor-associated antigen induce target-cell lysis by resting NK cells and by a subset of NK clones. International journal of cancer Journal international du cancer. 1991;48(2):227–233. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910480213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gleason MK, Verneris MR, Todhunter DA, Zhang B, McCullar V, Zhou SX, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Weiner LM, Vallera DA, Miller JS. Bispecific and trispecific killer cell engagers directly activate human NK cells through CD16 signaling and induce cytotoxicity and cytokine production. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2012;11(12):2674–2684. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiernik A, Foley B, Zhang B, Verneris MR, Warlick E, Gleason MK, Ross JA, Luo X, Weisdorf DJ, Walcheck B, Vallera DA, Miller JS. Targeting Natural Killer Cells to Acute Myeloid Leukemia In Vitro with a CD16 × 33 Bispecific Killer Cell Engager and ADAM17 Inhibition. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19(14):3844–3855. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gleason MK, Ross JA, Warlick ED, Lund TC, Verneris MR, Wiernik A, Spellman S, Haagenson MD, Lenvik AJ, Litzow MR, Epling-Burnette PK, Blazar BR, Weiner LM, Weisdorf DJ, Vallera DA, Miller JS. CD16×CD33 bispecific killer cell engager (BiKE) activates NK cells against primary MDS and MDSC CD33+ targets. Blood. 2014;123(19):3016–3026. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-533398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vallera DA, Zhang B, Gleason MK, Oh S, Weiner LM, Kaufman DS, McCullar V, Miller JS, Verneris MR. Heterodimeric Bispecific Single-Chain Variable-Fragment Antibodies Against EpCAM and CD16 Induce Effective Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity Against Human Carcinoma Cells. Cancer biotherapy & radiopharmaceuticals. 2013 doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen X, Zaro JL, Shen WC. Fusion protein linkers: property, design and functionality. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65(10):1357–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huston JS, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, Tai MS, Novotny J, Margolies MN, Ridge RJ, Bruccoleri RE, Haber E, Crea R, et al. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an anti-digoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(16):5879–5883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Whitlow M, Bell BA, Feng SL, Filpula D, Hardman KD, Hubert SL, Rollence ML, Wood JF, Schott ME, Milenic DE, et al. An improved linker for single-chain Fv with reduced aggregation and enhanced proteolytic stability. Protein Eng. 1993;6(8):989–995. doi: 10.1093/protein/6.8.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jager V, Bussow K, Wagner A, Weber S, Hust M, Frenzel A, Schirrmann T. High level transient production of recombinant antibodies and antibody fusion proteins in HEK293 cells. BMC Biotechnol. 2013;13:52. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-13-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sorensen HP, Mortensen KK. Advanced genetic strategies for recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol. 2005;115(2):113–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nakayama H, Shimamoto N. Modern and simple construction of plasmid: saving time and cost. J Microbiol. 2014;52(11):891–897. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4501-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gibson DG, Benders GA, Andrews-Pfannkoch C, Denisova EA, Baden-Tillson H, Zaveri J, Stockwell TB, Brownley A, Thomas DW, Algire MA, Merryman C, Young L, Noskov VN, Glass JI, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Complete chemical synthesis, assembly, and cloning of a Mycoplasma genitalium genome. Science. 2008;319(5867):1215–1220. doi: 10.1126/science.1151721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gopal GJ, Kumar A. Strategies for the production of recombinant protein in Escherichia coli. Protein J. 2013;32(6):419–425. doi: 10.1007/s10930-013-9502-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Burgess RR. Refolding solubilized inclusion body proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:259–282. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lichty JJ, Malecki JL, Agnew HD, Michelson-Horowitz DJ, Tan S. Comparison of affinity tags for protein purification. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41(1):98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kim JY, Kim YG, Lee GM. CHO cells in biotechnology for production of recombinant proteins: current state and further potential. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(3):917–930. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3758-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reff ME, Carner K, Chambers KS, Chinn PC, Leonard JE, Raab R, Newman RA, Hanna N, Anderson DR. Depletion of B cells in vivo by a chimeric mouse human monoclonal antibody to CD20. Blood. 1994;83(2):435–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Harrison D, Phillips JH, Lanier LL. Involvement of a metalloprotease in spontaneous and phorbol ester-induced release of natural killer cell-associated Fc gamma RIII (CD16-II) J Immunol. 1991;147(10):3459–3465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Borrego F, Lopez-Beltran A, Pena J, Solana R. Downregulation of Fc gamma receptor IIIA alpha (CD16-II) on natural killer cells induced by anti-CD16 mAb is independent of protein tyrosine kinases and protein kinase C. Cellular immunology. 1994;158(1):208–217. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grzywacz B, Kataria N, Verneris MR. CD56(dim)CD16(+) NK cells downregulate CD16 following target cell induced activation of matrix metalloproteinases. Leukemia. 2007;21(2):356–359. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404499. author reply 359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu Q, Sun Y, Rihn S, Nolting A, Tsoukas PN, Jost S, Cohen K, Walker B, Alter G. Matrix metalloprotease inhibitors restore impaired NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Journal of virology. 2009;83(17):8705–8712. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02666-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Edsparr K, Speetjens FM, Mulder-Stapel A, Goldfarb RH, Basse PH, Lennernas B, Kuppen PJ, Albertsson P. Effects of IL-2 on MMP expression in freshly isolated human NK cells and the IL-2-independent NK cell line YT. J Immunother. 2010;33(5):475–481. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181d372a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Romee R, Foley B, Lenvik T, Wang Y, Zhang B, Ankarlo D, Luo X, Cooley S, Verneris M, Walcheck B, Miller J. NK cell CD16 surface expression and function is regulated by a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17 (ADAM17) Blood. 2013;121(18):3599–3608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-425397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhou Q, Gil-Krzewska A, Peruzzi G, Borrego F. Matrix metalloproteinases inhibition promotes the polyfunctionality of human natural killer cells in therapeutic antibody-based anti-tumour immunotherapy. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2013;173(1):131–139. doi: 10.1111/cei.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Romee R, Leong JW, Fehniger TA. Utilizing cytokines to function-enable human NK cells for the immunotherapy of cancer. Scientifica. 2014;2014:205796. doi: 10.1155/2014/205796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]