Abstract

Background

Nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems exhibit promising therapeutic efficacy in cancer chemotherapy. However, ideal nano drug carriers are supposed to be sufficiently internalized into cancer cells and then release therapeutic cargoes in response to certain intracellular stimuli, which has never been an easy task to achieve.

Objective

This study is to design mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs)-based pH-responsive nano drug delivery system that is effectively internalized into cancer cells and then release drug in response to lysosomal/endosomal acidified environment.

Methods

We synthesized MSNs by sol-gel method. Doxorubicin (DOX) was encapsulated into the pores as a model drug. Polyaspartic acid (PAsA) was anchored on the surface of mesoporous MSNs (P-MSNs) as a gatekeeper via amide linkage and endowed MSNs with positive charge.

Results

In vitro release analysis demonstrated enhanced DOX release from DOX-loaded PAsA-anchored MSNs (DOX@P-MSNs) under endosomal/lysosomal acidic pH condition. Moreover, more DOX@P-MSNs were internalized into HepG2 cells than DOX-loaded MSNs (DOX@MSNs) and free DOX revealed by flow cytometry. Likewise, confocal microscopic images revealed that DOX@P-MSNs effectively released DOX and translocated to the nucleus. Much stronger cytotoxicity of DOX@P-MSNs against HepG2 cells was observed compared with DOX@MSNs and free DOX.

Conclusion

DOX@P-MSNs were successfully fabricated and achieved pH-responsive DOX release. We anticipated this nanotherapeutics might be suitable contenders for future in vivo cancer chemotherapeutic applications.

Keywords: cancer chemotherapy, mesoporous silica nanoparticles, polyaspartic acid, pH-responsive release, cytotoxicity

Introduction

Nanomaterials have achieved ample consideration for delivery of therapeutic drugs or bioactive molecules in the biomedical field over the years.1–5 They have large advantages in drug delivery applications on account of their facility to improve solubility of less water-soluble drugs, control drug pharmacokinetics, increase drug half-life through decreasing immunogenicity, increase selectivity toward target cells or tissue to minimize side effects of the therapeutic drug, support more controllable drug release, and deliver two or more drugs for combination therapy. Current revolutions on morphology control and external surface anchoring of inorganic nanoparticle-based transporters, particularly mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs), have attained more attention in this scenario.6–16

MSNs are composed of honeycomb-like mesoporous structures to encapsulate comparatively large amounts of cargo molecules. MSNs have several benefits as delivery vehicles over other inorganic nanoparticles, including brilliant biocompatibility and biological stability, high thermal stability (even up to 900°C), tunable pore size to encapsulate cargo molecules, high surface area (up to 1,000 m2/g or even more), large pore volume (up to 1 cm3/g) and ease in surface customization.17–23 Recently, several MSN-based stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems have been reported for cancer chemotherapy, mainly because of their surface conjugation ability with stimuli-responsive materials that can offer more benefits in many aspects, including innocuous transportation of guest molecules (ie, drugs or bioactive molecules) to specific sites in the body; on-demand release in response to either exterior triggers or internal cellular stimuli such as pH, temperature, enzymes, light, redox agents; and so on.24–29 The on-demand release behavior is generally regulated through the on/off of mesopores by anchoring different gatekeepers on their outlets.30–40 However, the complexity of cancer malignancy still demands more efforts from researchers to resolve this severe current dilemma.

Herein, we have designed doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticles (symbolized as DOX@P-MSNs) that demonstrate pH- responsive in vitro and intracellular drug release (Scheme 1). To pursue our supposition, we first synthesized MSNs and then functionalized them with (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTES). APTES-modified MSNs (NH2-MSNs) were then anchored with polyaspartic acid (PAsA) as a gatekeeper that closed the outlets of mesopores to control premature doxorubicin (DOX) release under physiological conditions, and permitted pore outlets to open in response to acidified endosomal/lysosomal cellular compartments, to let DOX diffuse out. PAsA is chosen as a pore outlet capping agent on account of its biodegradability, nontoxicity toward biological systems and, more importantly, making nanoparticles positively charged after conjugation, which helps their cellular uptake due to interaction with negatively charged cellular components.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of DOX@P-MSNs synthesis and their pH-responsive DOX release.

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; APTES, (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane; PAsA, polyaspartic acid; DOX@MSN, doxorubicin-loaded MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tetraethylorthosilicate (TEOS), N-cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC⋅HCl), doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX⋅HCl), diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were provided by Sigma Aldrich Co. (St Louis, MO, USA). APTES and sodium salt of PAsA were obtained from Aladdin (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), 37% pure hydrochloric acid, methanol, anhydrous ethanol, DMSO, ammonium hydroxide and several other commonly used laboratory reagents were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, People’s Republic of China). All these chemicals were used in the original form as purchased from the relevant manufacturing company without any further purification. Ultra nanopure distilled water (18.2 MΩ) was used throughout the practical work.

Cell culture

The human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells were provided by Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in the DMEM culture medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified and 5% CO2 incubator.

Synthesis of MSNs and surface anchoring

Highly dispersed MSNs were synthesized through a base-catalyzed reaction by sol–gel process.18 Briefly, CTAB (0.5 g) and NaOH (0.2 g) were dissolved in ultra nanopure distilled water (200 mL) and then heated up to 80°C with constant magnetic stirring. When temperature of the solution approached 80°C, TEOS (5 mL) was added dropwise with continuous stirring and then nanoparticles were kept for the next 2 h under the same conditions. As-synthesized silica nanoparticles were then centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min, washed with pure water and methanol several times and dried in air. To remove surfactant templates, nanoparticles were redispersed in a warm acidic methanol (2 mL HCl and 120 mL methanol) for 24 h and then again centrifuged, washed with methanol and water and dried at 80°C under vacuum conditions.

To anchor the -NH2 group on the surface of MSNs, APTES modification was achieved by refluxing APTES (100 µL) and the prepared MSNs (100 mg) in methanol for 24 h with constant magnetic stirring. The product was collected by centrifugation after washing several times with methanol and water. The as-obtained nanoparticles symbolized as NH2-MSNs were then dried under high vacuum at 60°C to extract solvent molecules from the mesoporous structure completely. For transmission electron microscope (TEM) images, nanoparticles were dispersed in methanol, dropped on copper gird and then dried in air.

PAsA anchoring on the surface of nanoparticles by amidation

Sodium salt of PAsA was dissolved in ethanol (3 mg/mL) and then PAsA was conjugated on the surface of MSNs via amide linkage between the surface NH2 group of MSNs and the carboxylic group of PAsA. Briefly, 300 mg of NH2-MSNs were refluxed in acetate buffer (50 mL, pH 7.0) followed by addition of PAsA and EDC/N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) mixture (EDC =0.2 M, NHS =0.2 M) dropwise, and then, the suspension was allowed to stir overnight at ambient temperature. After overnight stirring, PAsA-conjugated MSNs, termed P-MSNs, were centrifuged, rinsed with copious amounts of distilled water to remove excessive PAsA and remaining solvent molecules, and then dried overnight at 45°C.

Construction of DOX@P-MSNs

DOX⋅HCl was dissolved in distilled water (3 mg/mL) and NH2-MSNs (100 mg) were dispersed in the DOX solution, followed by constant stirring for the next 36 h at 37°C to diffuse more DOX inside pores. Then PAsA and EDC/NHS mixtures were added dropwise, followed by stirring for a further 6 h at ambient conditions. Finally, DOX@P-MSNs were centrifuged and rinsed gently with distilled water to remove excess PAsA and surface-adsorbed DOX. DOX@P-MSNs were subjected to freeze-drying for the following experiments. The drug-loading capacity of silica nanoparticles was determined from the difference in concentration of the initial and left drug in solution by using ultraviolet (UV)–vis absorbance readout according to a standard curve.

Characterization of DOX@P-MSNs

The size and zeta potential of nanoparticles were determined in aqueous suspension by using dynamic light scattering (DLS; Zetasizer Nano-ZS 90; Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The morphology of nanoparticles was observed by transmission electron microscopy (Tecnai G2 20; FEI, Eindhoven, the Netherlands). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of nanoparticles was performed by Pyris TG Analyzer (PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) using nitrogen as an oxidant with continuous heating rate of 10°C/min from 30°C to 796.84°C. N2-absorption/desorption analysis was performed by using an ASAP 2020 sorptometer (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA) at a constant temperature of 77 K.

In vitro pH-responsive DOX release

To study pH-triggered DOX release, 3 mg of DOX@P-MSNs were suspended in 1 mL of PBS solution with different pH values (7.4, 6.5, 5.5 or 4.5) in cellulose membrane bags (molecular weight cutoff [MWCO] =5,300), and then, each bag was immersed in of PBS buffer with corresponding pH values and stirred at 37°C. Subsequently, a 1 mL sample was taken from each PBS solution at known time intervals, DOX release was measured through absorbance on the UV-vis spectrometer at λmax (488 nm) and then the sample was returned to the PBS bag again. The DOX release percentage was calculated from total loaded DOX in MSNs and released DOX under each pH condition during designated time intervals.

Cellular uptake

To investigate intracellular accumulation of DOX@P-MSNs, HepG2 cells were cultured in a 12-well plate at the density of 3×105 cells/well. After overnight culture, cells were washed with PBS and then treated with free DOX, doxorubicin-loaded MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticles (DOX@MSNs) and DOX@P-MSNs at an equivalent concentration of 2 µg/mL. The cells incubated with blank MSNs were considered as a control. After designated time intervals, cells were washed several times with PBS, trypsinized, washed again with PBS and then finally suspended in 300 µL of PBS for intracellular DOX fluorescence measurement by a low cytometer (FC500; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) with argon laser excitation at 488 nm and FL2 detection channel.

Intracellular DOX release

To monitor intracellular DOX fluorescence via a confocal microscope, HepG2 cells were cultured overnight on a cover glass in a six-well plate at a density of 1×105 cells/well. Subsequently, cells were washed well and then incubated with free DOX, DOX@MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs at an equivalent DOX concentration of 3 µg/mL. At the designated time points, the cells were washed well with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and then cell nuclei were stained with DAPI (5 µg/mL) for 15 min. Finally, the cover glass was mounted on a slide for confocal microscopic examinations (Olympus FV1000; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). DOX fluorescence was observed at λex of 488 nm and λem of 550–580 nm.

Cellular cytotoxicity

HepG2 cells were grown overnight in a 24-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/well. After overnight culture, the cells were treated with MSNs, P-MSNs, free DOX, DOX@MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs with different DOX concentrations. After 24 h treatment, 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added into each well and incubated for the next 4 h. The culture medium was then removed, and 150 µL of DMSO was added to solubilize the formazan crystals. After incubation for at least 15–20 min, optical density was measured through a microplate reader at a wavelength of 490 nm. This experiment was repeated three times, and at least six replicates of each concentration were produced at the same time.

Results and discussion

Construction and characterization of DOX@P-MSNs

MSNs were produced through a base-catalyzed reaction by a sol–gel process involving the use of CTAB as a surfactant and TEOS as a silica precursor.18 Synthesized MSNs were insoluble in aqueous media, and their surface anchoring with the –NH2 group was achieved via APTES modification. Considering the controlled triggered-release mechanism, PAsA was anchored on the surface of MSNs to block pore outlets after drug loading to avoid its premature release under normal physiological conditions and to achieve pH-switched release under endosomal/lysosomal acidified environment. PAsA was anchored on the amine-functionalized surface of MSNs through acid-sensitive amide coupling in the presence of EDC/NHS. FTIR spectra of MSNs, NH2-MSNs and PAsA-MSNs (Figure S1) showed that the peak at 3,400 cm−1 was assigned to the Si-OH group of silica nanoparticles or water molecules adsorbed on their surface. Vibration peaks in the range of 400–1,400 cm−1 were assigned to symmetric stretching and bending of Si-O-Si bond. The peak in the range of 1,600–1,700 cm−1 was attributed to COOH of PAsA, while the peak in the range of 2,600–2,700 cm−1 was attributed to the NH2 group of PAsA, confirming covalent coupling of PAsA on the surface of MSNs. The band at 3,400 cm−1 due to Si-OH became weaker after APTES modification and PAsA conjugation. These results suggested that APTES and PAsA were successfully anchored on the surface of MSNs.

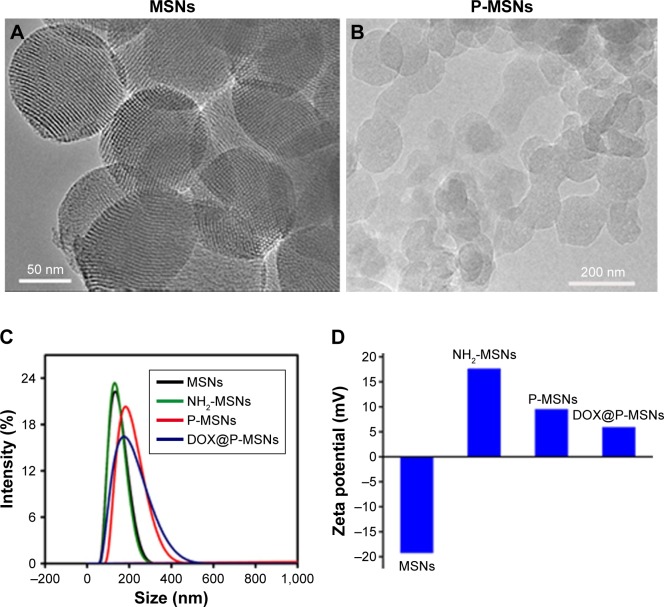

TEM images showed the well-ordered hexagonal mesopores all over the surface of MSNs that were large enough for loading DOX (Figure 1A). No porous structure was seen on the surface of MSNs after PAsA conjugation (P-MSNs; Figure 1B), confirming successful conjugation of PAsA on the surface of NH2-MSNs. DLS analysis showed that conjugation of PAsA increased the size of MSNs, but DOX loading did not markedly change the size of MSNs (Figure 1C and Table S1). The zeta potentials of MSNs, NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs in aqueous suspension were −19.32, +16.55, +7.80 and +6.17 mV, respectively (Figure 1D), indicating a positively charged surface of DOX@P-MSNs. The negative charge of MSNs was assigned to the surface Si-OH group while the charge turned to positive after APTES modification. The reason why the positive feature decreased after PAsA conjugation was mainly due to the presence of the –COOH group.

Figure 1.

Characterization of DOX@P-MSNs.

Notes: (A) TEM images of MSNs. (B) TEM images of P-MSNs. (C) The hydrodynamic size of MSNs, NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs. (D) Zeta potential of MSNs, NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs.

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; TEM, transmission electron microscope; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

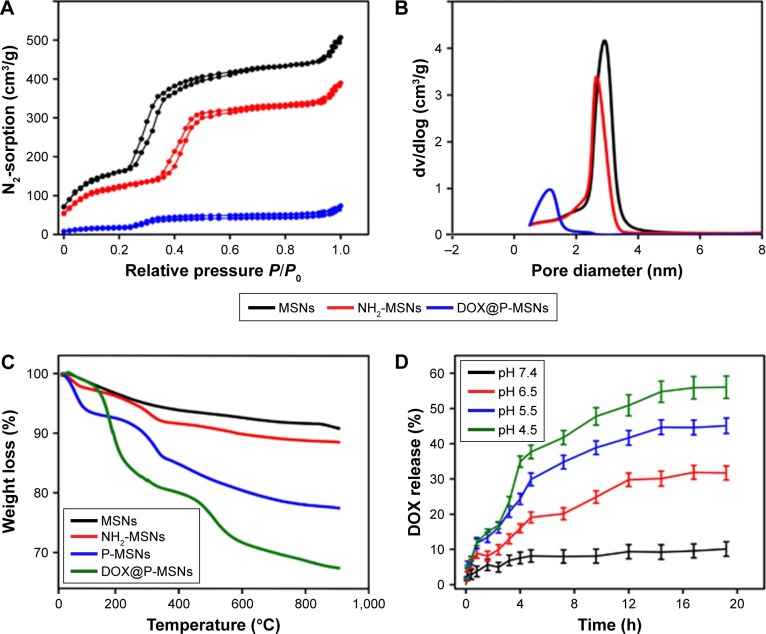

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms as shown in Figure 2A indicated a characteristic type of isotherm with P/P0 value ranging from 0.4 to 0.5. The relatively high value of their specific surface area was calculated from the linear part of Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) plot, which reached 863 m2/g with a pore volume of 0.87 m3/g, suggesting that our synthesized silica nanoparticles were ideal materials for hosting guest drug molecules of various sizes, morphologies and functionalities. The pore size of nanoparticles was calculated from their corresponding adsorption isotherms by using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method. The average pore size of MSNs was almost 2.89 nm (Figure 2B), which was consistent with the TEM image (Figure 1A). Moreover, a little diminution in nitrogen adsorption in the case of NH2-MSNs was attributed to a slight decrease in pore size after APTES anchoring, which could be due to conjugation of –NH2 on the pore interior and on the outer surface of MSNs. In contrast to MSNs and NH2-MSNs, a negligible nitrogen adsorption was detected in DOX@P-MSNs, which might be because DOX loading occupied the pores, resulting in a decreased nitrogen adsorption.

Figure 2.

Characterization and in vitro drug release of DOX@P-MSNs.

Notes: (A) N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of MSNs, NH2-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs. (B) Pore diameter distribution of MSNs, NH2-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs. (C) TGA curves of MSNs, NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs. (D) pH-responsive DOX release from DOX@P-MSNs in PBS with different pH values. Data show mean ± standard deviation (n=3).

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; TGA, thermogravimetric analysis; DOX, doxorubicin.

TGA curves of MSNs, NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs showed that NH2-MSNs, P-MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs yielded more weight loss than MSNs (Figure 2C), which was attributed to the degradation of organic components, ie, APTES, PAsA and DOX. APTES, PAsA and DOX were vulnerable under such a high thermal condition, while silica material was very stable up to 900°C or even more.

pH-responsive DOX release in vitro

To evaluate the controlled pH-responsive drug release behavior from P-MSNs, we loaded DOX⋅HCl as a model anticancer drug into P-MSNs whose loading efficiency determined by UV–vis spectroscopy was ~6.5% by weight. NH2-MSNs were soaked in DOX solution overnight, and then, pore outlets were blocked by PAsA conjugation. The in vitro drug release of DOX@P-MSNs dispersed in PBS solutions of different pH conditions (pH values mimicking normal physiological conditions, tumor microenvironment and cellular endosomal/lysosomal compartments) was evaluated (Figure 2D). Merely 10% of DOX was released at pH 7.4, suggesting well encapsulation of DOX molecules inside the pores during physiological blood circulation. However, DOX release increased with the diminution of pH value in PBS. Maximum DOX release of almost 56% was achieved in the PBS solution at pH 4.5. The reason for more DOX release could be the protonation of the NH2 group in acidified conditions involving amide linkage between MSNs and PAsA. The protonation of the NH2 group could result in bond cleavage that left pores open to diffuse DOX out. The abovementioned results suggested that PAsA gatekeepers could retain DOX inside the pores of MSNs to avoid premature DOX release under normal physiological conditions but degraded in acidified endosomal/lysosomal compartments to encourage DOX release.

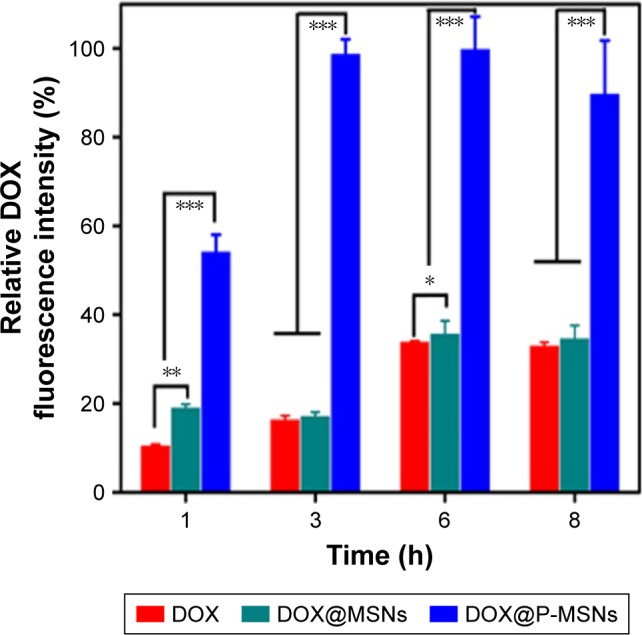

Cellular uptake of DOX@P-MSNs

Efficient cellular internalization of the nanodrug delivery system is a prerequisite for effective therapeutic applications. It has been widely acknowledged that positively charged nanoparticles are internalized more easily into cells than their negatively charged counterparts.41 To investigate the cellular uptake of DOX@P-MSNs, we treated HepG2 cells with free DOX, DOX@MSNs or DOX@P-MSNs at different time points. Flow cytometric analysis showed that fluorescence intensity of DOX increased in a time-dependent manner in these treated cells. However, significantly more DOX fluorescence was observed in DOX@P-MSNs-treated cells as compared with free DOX- and DOX@MSNs-treated cells (Figure 3). These results revealed that DOX@P-MSNs were more effectively internalized into the cells, which might be due to their positively charged feature on the outer surface that resulted in enhanced interaction with the cellular membrane. To further vividly observe the intracellular accumulation, HepG2 cells were incubated with different doses of DOX@P-MSNs at different time intervals. Confocal microscopy confirmed that intracellular DOX@P-MSN increased in a dose- and incubation time-dependent manner (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

Cellular uptake when HepG2 cells were treated with free DOX, DOX@ MSNs or DOX@P-MSNs at an equivalent DOX concentration of 2 µg/mL for different time intervals by flow cytometry.

Notes: Data show mean ± standard deviation (n=6). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; DOX@MSN, doxorubicin-loaded MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

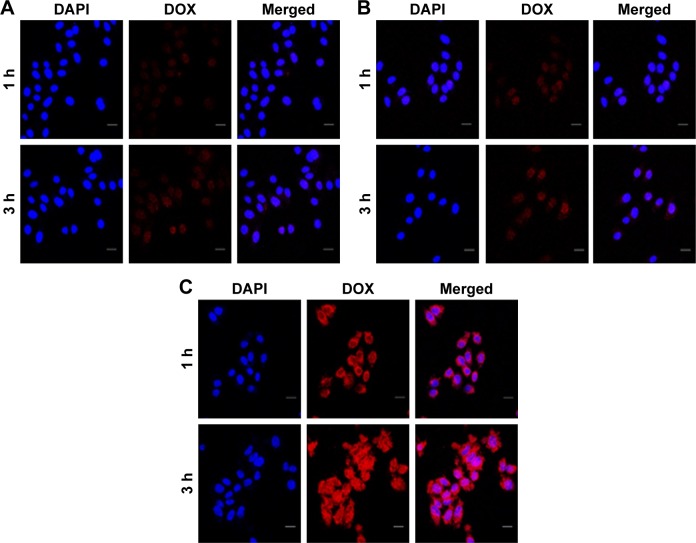

Intracellular DOX release of DOX@P-MSNs

After internalization into cancer cells, DOX@P-MSNs needed to efficiently release DOX to the nucleus to exert cytotoxicity. To explore the intracellular DOX release, HepG2 cells were treated with free DOX, DOX@MSNs and DOX@P-MSNs at the DOX concentration of 3 µg/mL for different time intervals and confocal microscopy was used to determine the colocalization of DOX in the nucleus. As shown in Figure 4A and B, a faint DOX fluorescence was observed in the cells treated with free DOX and DOX@ MSNs for 1 h. Although there was more DOX fluorescence after 3 h incubation with free DOX and DOX@MSNs, abundant DOX fluorescence was visualized in cells treated with DOX@P-MNPs, even for 1 h (Figure 4C). On the other hand, no DOX fluorescence was visualized in the nucleus even after 3 h treatment with free DOX and only a faint fluorescence was detected in the nucleus in the case of DOX@MSNs. In contrast, ample DOX fluorescence was observed in the nucleus of cells treated with DOX@P-MSNs for 3 h. These results confirmed that DOX@P-MSNs were efficiently internalized into cells, went through pore outlet opening in acidic lysosomal conditions to diffuse DOX out and then translocated toward the nucleus to exert efficient cytotoxicity.

Figure 4.

Cellular uptake and intracellular drug release of DOX@P-MSNs.

Notes: Confocal microscopic images of HepG2 cells incubated with (A) free DOX, (B) DOX@MSNs or (C) DOX@P-MSNs at an equivalent DOX concentration of 3 µg/mL for different time intervals. Scale bar is 20 µm.

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin; DOX@MSN, doxorubicin-loaded MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DAPI, diamidino-2-phenylindole.

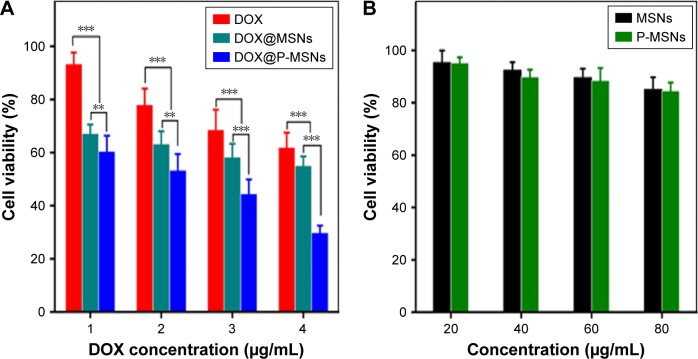

In vitro cytotoxicity of DOX@P-MSNs

Given that DOX@P-MSNs exhibited efficient cellular uptake and intracellular drug release, the biological function of DOX@P-MSNs was evaluated. HepG2 cells were treated with free DOX, DOX@MSNs or DOX@P-MSNs at different DOX concentrations for 24 h and then their cytotoxicity was determined by MTT assay. As expected, all treatments induced cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells in a dose-dependent manner. However, DOX@P-MSNs exhibited the strongest cytotoxicity compared with free DOX and DOX@MSNs (Figure 5A). Almost 73% inhibition was observed in DOX@P-MSN-treated cells, while only 30% and 33% inhibition were observed in the case of free DOX and DOX@MSNs treatment at a DOX concentration of 4 µg/mL, respectively. In the meanwhile, treatment with MSNs and P-MSNs did not result in significant cytotoxicity against HepG2 cells, even up to 80 µg/mL concentration (Figure 5B). These results suggested that DOX@P-MSNs exhibited strong cytotoxicity, which might be related to enhanced internalization and intracellular drug release.

Figure 5.

Cell viability of HepG2 cells.

Notes: (A) Cell viability of HepG2 cells after incubation with free DOX, DOX@MSNs or DOX@P-MSNs with different concentrations of DOX for 24 h by MTT assay. (B) Cell viability of HepG2 cells after incubation with different concentrations of MSNs or P-MSNs for 24 h by MTT assay. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (n=6). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001.

Abbreviations: DOX, doxorubicin; DOX@MSN, doxorubicin-loaded MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; MTT, 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide.

Conclusion

We have successfully synthesized PAsA-anchored MSNs to load anticancer drug DOX. Conjugation with PAsA endows MSNs with a positive charge, which contributes to efficient cellular uptake by HepG2 cells. After internalization into cells, PAsA blocking of the mesopore outlets to control premature DOX release under physiological conditions lets pore outlets open in response to acidified endosomal/lysosomal compartments, resulting in intracellular DOX release and translocation to the nucleus to exert efficient cytotoxicity. We anticipate that this MSN-based nanodrug delivery system could be effective for in vivo chemotherapeutic applications in a future perspective.

Supplementary materials

FTIR spectra of MSNs, NH2-MSNs and P-MSNs.

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; PAsA, polyaspartic acid.

Confocal microscopic images of HepG2 cells treated with DOX@P-MSNs at different DOX concentrations (1, 2, 3 and 4 µg/mL) for various time periods (1, 2, 4 and 6 h).

Note: Scale bar is 20 µm.

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin.

Table S1.

Characterization of the nanoparticles

| Material | DLS size (nm) |

TEM size (nm) |

BET SA (m2/g) |

Pore volume (cm3/g) |

Pore size (nm) |

ζ potential (mV) |

DLS PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSNs | 104 | 98 | 863 | 0.87 | 2.89 | −19.32 | 0.167 |

| NH2-MSNs | 121 | 116 | 798 | 0.76 | 2.65 | +16.55 | 0.234 |

| P-MSNs | 182 | 178 | 580 | – | – | +9.01 | 0.192 |

| DOX@P-MSNs | 191 | 189 | 557 | – | – | +6.17 | 0.217 |

Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; TEM, transmission electron microscope; BET, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller; PDI, polydispersity index; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; SA, surface area; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2015CB931802) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672937, 81473171, 81372400 and 31371423). We thank the Analytical and Testing Centre of Huazhong University of Science and Technology for related analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lee DE, Koo H, Sun IC, Ryu JH, Kim K, Kwon IC. Multifunctional nanoparticles for multimodal imaging and theragnosis. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(7):2656–2672. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15261d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mallick N, Anwar M, Asfer M, et al. Chondroitin sulfate-capped super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as potential carriers of doxorubicin hydrochloride. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;151:546–556. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.05.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tu H, Lu Y, Wu Y, et al. Fabrication of rectorite-contained nanoparticles for drug delivery with a green and one-step synthesis method. Int J Pharm. 2015;493(1–2):426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian J, Xu S, Deng H, et al. Fabrication of self-assembled chitosan-dispersed LDL nanoparticles for drug delivery with a one-step green method. Int J Pharm. 2016;517(1–2):25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das D, Rameshbabu AP, Ghosh P, Patra P, Dhara S, Pas S. Biocompatible nanogels derived from functionalized dextrin for targeted delivery for doxorubicin hydrochloride. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;171:27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jian J, Hu T, Jiajia C, et al. Rectorite-intercalated nanoparticles for improving controlled release of doxorubicin hydrochloride. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;101:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dong M, Qian-Ming L, Li-Ming Z, Yuan-Yuan L, Xue W. A star-shaped porphyrin-arginine functionalized poly (L-lysine) Copolymer for photo-enhanced drug and gene co-delivery. Biomaterials. 2014;35(14):4357–4367. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou X, Zheng Q, Wang C, et al. Star-shaped amphiphilic hyper-branched polyglycerol conjugated with dendritic poly(L-lysine) for the codelivery of docetaxel and MMP-9 siRNA in cancer therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(20):12609–12619. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Duan J, Cai L, Ma D, Xue W. Supramolecular aggregate as a high-efficiency gene carrier mediated with optimized assembly structure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8(43):29343–29355. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b11390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daniela I, Alessandro P, Marina S, et al. Graphene quantum dots for cancer targeted drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2017;518(1–2):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Afnan M, Lin D, Azza A, Rachid S, Guangchao W, Niveen MK. Zippered release from polymer-gated carbon nanotubes. J Mater Chem. 2012;22:11503–11508. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alessandro P, Daniela I, Shabana A, et al. Tunable doxorubicin release from polymer-gated multiwall carbon nanotubes. Int J Pharm. 2016;515(1–2):30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slowing II, Trewyn BG, Giri S, Lin VY. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery and biosensing applications. Adv Fun Mater. 2007;17(8):1225–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu ZP, Zeng QH, Lu GQ, Yu AB. Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers for efficient cellular delivery. Chem Eng Sci. 2006;61(3):1027–1040. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Kim HS, Lee N, et al. Multifunctional uniform nanoparticles composed of a magnetite nanocrystal core and a mesoporous silica shell for magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging and for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(44):8438–8441. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y, Miyoshi H, Nakamura M. Nanomedicine for drug delivery and imaging: a promising avenue for cancer therapy and diagnosis using targeted functional nanoparticles. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(12):2527–2537. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, et al. A mesoporous silica nanosphere-based carrier system with chemically removable CdS nanoparticle caps for stimuli-responsive controlled release of neurotransmitters and drug molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(15):4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang X, Li L, Liu T, et al. The shape effect of mesoporous silica nanoparticles on biodistribution, clearance, and biocompatibility in vivo. ACS Nano. 2011;5(7):5390–5399. doi: 10.1021/nn200365a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ambrogio MW, Thomas CR, Zhao YL, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. Mechanized silica nanoparticles: a new frontier in theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):903–913. doi: 10.1021/ar200018x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang F, Li L, Chen D. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, bio-compatibility and drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24(12):1504–1534. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a delivery system for hydrophobic anticancer drugs. Small. 2007;3(8):1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang P, Quan Z, Lu L, Huang S, Lin J. Luminescence functionalization of mesoporous silica with different morphologies and applications as drug delivery systems. Biomaterials. 2008;29(6):692–702. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YS, Haynes CL. Impacts of mesoporous silica nanoparticle size, pore ordering, and pore integrity on hemolytic activity. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(13):4834–4842. doi: 10.1021/ja910846q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang H, Guo J, Sun Y, Chang B, Ren Q, Yang W. Facile synthesis of pH sensitive polymer-coated mesoporous silica nanoparticles and their application in drug delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 2011;421(2):388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallet-Regí M, Balas F, Arcos D. Mesoporous materials for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46(40):7548–7558. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan L, He Q, Liu J, et al. Nuclear-targeted drug delivery of TAT peptide-conjugated monodisperse mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(13):5722–5725. doi: 10.1021/ja211035w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JE, Lee N, Kim T, Kim J, Hyeon T. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanocomposite nanoparticles for theranostic applications. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44(10):893–902. doi: 10.1021/ar2000259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu F, Wu SH, Hung Y, Mou CY. Size effect on cell uptake in well-suspended, uniform mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5(12):1408–1413. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh N, Karambelkar A, Gu L, et al. Bioresponsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for triggered drug release. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(49):19582–19585. doi: 10.1021/ja206998x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baeza A, Guisasola E, Ruiz-Hernández E, Vallet-Regí M. Magnetically triggered multidrug release by hybrid mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2012;24(3):517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin Q, Huang Q, Li C, et al. Anticancer drug release from a mesoporous silica based nanophotocage regulated by either a one-or two-photon process. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(31):10645–10647. doi: 10.1021/ja103415t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan H, Teh C, Sreejith S, et al. Functional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for photothermal-controlled drug delivery in vivo. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;124(33):8498–8502. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wan X, Wang D, Liu S. Fluorescent pH-sensing organic/inorganic hybrid mesoporous silica nanoparticles with tunable redox-responsive release capability. Langmuir. 2010;26(19):15574–15579. doi: 10.1021/la102148x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C, Geng J, Pu F, Yang X, Ren J, Qu X. Polyvalent nucleic acid/mesoporous silica nanoparticle conjugates: dual stimuli-responsive vehicles for intracellular drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(4):882–886. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu J, Bu W, Pan L, Shi J. NIR-triggered anticancer drug delivery by upconverting nanoparticles with integrated azobenzene-modified mesoporous silica. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52(16):4375–4379. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu C, Guo J, Yang W, Hu J, Wang C, Fu S. Magnetic mesoporous silica microspheres with thermo-sensitive polymer shell for controlled drug release. J Mater Chem. 2009;19(27):4764–4770. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hakeem A, Duan R, Zahid F, et al. Dual stimuli-responsive nano-vehicles for controlled drug delivery: mesoporous silica nanoparticles end-capped with natural chitosan. Chem Commun (Camb) 2014;50(87):13268–13271. doi: 10.1039/c4cc04383a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hakeem A, Zahid F, Duan R, et al. Cellulose conjugated FITC-labelled mesoporous silica nanoparticles: intracellular accumulation and stimuli responsive doxorubicin release. Nanoscale. 2016;8(9):5089–5097. doi: 10.1039/c5nr08753h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu CL, Lu CH, Song XY, Yang HH, Wang XR. Bioresponsive controlled release using mesoporous silica nanoparticles capped with aptamer-based molecular gate. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(5):1278–1281. doi: 10.1021/ja110094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.You YZ, Kalebaila KK, Brock SL. Temperature-controlled uptake and release in PNIPAM-modified porous silica nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2008;20(10):3354–3359. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan YY, Mao CQ, Du XJ, Du JZ, Wang F, Wang J. Surface charge switchable nanoparticles based on zwitterionic polymer for enhanced drug delivery to tumor. Adv Mater. 2012;24(40):5476–5480. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FTIR spectra of MSNs, NH2-MSNs and P-MSNs.

Abbreviations: MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; PAsA, polyaspartic acid.

Confocal microscopic images of HepG2 cells treated with DOX@P-MSNs at different DOX concentrations (1, 2, 3 and 4 µg/mL) for various time periods (1, 2, 4 and 6 h).

Note: Scale bar is 20 µm.

Abbreviations: DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle; DOX, doxorubicin.

Table S1.

Characterization of the nanoparticles

| Material | DLS size (nm) |

TEM size (nm) |

BET SA (m2/g) |

Pore volume (cm3/g) |

Pore size (nm) |

ζ potential (mV) |

DLS PDI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSNs | 104 | 98 | 863 | 0.87 | 2.89 | −19.32 | 0.167 |

| NH2-MSNs | 121 | 116 | 798 | 0.76 | 2.65 | +16.55 | 0.234 |

| P-MSNs | 182 | 178 | 580 | – | – | +9.01 | 0.192 |

| DOX@P-MSNs | 191 | 189 | 557 | – | – | +6.17 | 0.217 |

Abbreviations: DLS, dynamic light scattering; TEM, transmission electron microscope; BET, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller; PDI, polydispersity index; MSN, mesoporous silica nanoparticle; SA, surface area; P-MSN, polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type MSN; DOX@P-MSN, doxorubicin-loaded polyaspartic acid-anchored MCM-41-type mesoporous silica nanoparticle.