Abstract

Preclinical findings support a role for α1-adrenergic antagonists in reducing nicotine motivated behaviors, but these findings have yet to be translated to humans. The current study evaluated whether doxazosin would attenuate stress-precipitated smoking in the human laboratory. Using a well-validated laboratory analogue of smoking-lapse behavior, this pilot study evaluated whether doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) versus placebo attenuated the effect of stress (vs. neutral imagery) on tobacco craving, the ability to resist smoking and subsequent ad-libitum smoking in nicotine-deprived smokers (n=35). Cortisol, adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), norepinephrine, epinephrine, and physiologic reactivity were assessed. Doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day versus placebo) decreased cigarettes per day during the 21-day titration period. Following titration, doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day versus placebo) decreased tobacco craving. During the laboratory session, doxazosin (8 mg/day versus placebo) further decreased tobacco craving following stress versus neutral imagery. Doxazosin increased the latency to start smoking following stress, and reduced the number of cigarettes smoked. Dosage of 8 mg/day doxazosin increased or normalized cortisol levels following stress imagery and decreased cortisol levels following neutral imagery. These preliminary findings support a role for the noradrenergic system in stress-precipitated smoking behavior, and support further development of doxazosin as a novel pharmacotherapeutic treatment strategy for smoking cessation.

Keywords: smoking, smoking cessation, noradrenergic, stress, doxazosin

INTRODUCTION

Cigarette smoking affects nearly 17.8% of adults in the United States (Jamal et al., 2014), with over 556,000 deaths per year attributable to smoking-related causes (Carter et al., 2015). Worldwide, tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality (World Health Organization, 2012). However, smokers often fail to maintain long-term abstinence even with the most efficacious treatments (Fiore et al., 2008; Jorenby et al., 2006). This could be due, in part, to the fact that most current treatments for smoking cessation target decrements in nicotine-related reinforcement or withdrawal-like symptoms. Stress is another primary mechanism involved with the maintenance of and relapse to smoking (McKee et al., 2003). Thus, targeting brain stress pathways as a novel pharmacotherapeutic treatment strategy for stress-precipitated smoking may be of clinical benefit.

The noradrenergic system, a system widely involved in the stress response, has been shown to play a key role in mediating the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse, including nicotine, alcohol, cocaine, and heroin. With regard to nicotine, human laboratory studies investigating the effects of the noradrenergic system on smoking behavior have been limited but demonstrate efficacy in reducing nicotine-motivated behaviors. Noradrenergic medications have demonstrated efficacy in reducing tobacco craving and self-reported acute effects of nicotine, smoking self-administration, and withdrawal-like symptoms associated with smoking abstinence (Gourlay et al., 2004; McKee et al., 2015; Sofuoglu et al., 2003; Sofuoglu et al., 2006). Recent work from our laboratory, and work using the same human laboratory analogue of smoking-lapse behavior as the present investigation, demonstrated that stress reduced the ability to resist smoking and increased subsequent ad-libitum smoking in nicotine-deprived smokers (McKee et al., 2015). In this study, guanfacine, an α2a-adgrenegic agonist, either eliminated or reduced the effect of stress on latency to initiate smoking, ad-libitum smoking, and tobacco craving (McKee et al., 2015).

Preclinical models demonstrate that stress, via pharmacological provocation of the noradrenergic system, reinstated extinguished nicotine-seeking behavior and increased progressive ratio (PR) breakpoints and infusions of nicotine (Feltenstein et al., 2012; Grella et al., 2014; Li et al., 2014). Conversely, agents that blunt noradrenergic signaling have been found to attenuate stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking (Yamada and Bruijnzeel, 2011; Zislis et al., 2007) and decrease somatic signs associated with nicotine withdrawal (Bruijnzeel et al., 2010). Of interest to the present investigation, prazosin, an α1-adrenergic antagonist, has been shown to reduce nicotine self-administration (Forget et al., 2010), decrease reinstatement of nicotine-seeking induced by a nicotine prime or cue (Forget et al., 2010), reduce elevations in brain reward thresholds associated with nicotine withdrawal (Bruijnzeel et al., 2010), and attenuate nicotine-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens, a brain region necessary for the reward associated with drugs of abuse (Villegier et al., 2007).

The α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist doxazosin is structurally similar to prazosin and, clinically, has a more manageable dosing profile. Doxazosin has a half-life of approximately 22 hours requiring once daily dosing, whereas prazosin has a half-life of approximately 2–3 hours requiring multiple daily doses of the drug (Akduman and Crawford, 2001; Elliott et al., 1986). Thus, the clinical utility of prazosin may be limited as individuals may not reliably adhere to a multiple daily medication administration regimen. To date, doxazosin has been investigated in rodents and humans as a potential pharmacotherapeutic treatment strategy for alcohol and cocaine dependence. Doxazosin decreased voluntary alcohol intake in a 2-hour, 2-bottle choice paradigm in alcohol preferring (P) rats (O’Neil et al., 2013), and in a recent proof-of-concept double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial, doxazosin was efficacious in reducing drinks per week and heavy drinking days in alcohol dependent individuals with a high family history density of alcoholism (Kenna et al., 2016). With regard to cocaine, doxazosin (4 mg/day) decreased the positive subjective effects (i.e., ‘stimulated’, ‘like cocaine’, ‘likely to use cocaine if had access’) of intravenous (IV) cocaine in non-treatment seeking, cocaine dependent individuals (Newton et al., 2012). In treatment-seeking, cocaine dependent individuals, doxazosin (4 week titration; 8 mg/day) reduced cocaine use and increased the percentage of individuals that maintained cocaine abstinence for two or more consecutive weeks (Shorter et al., 2013).

Using a well-validated human laboratory analogue of smoking-lapse behavior, we examined whether doxazosin (0, 4 and 8 mg/day) attenuated the effect of stress (vs. neutral imagery) on the ability to resist smoking and subsequent ad-libitum smoking in nicotine-deprived smokers (n=35). To our knowledge, doxazosin has yet to be evaluated in a human laboratory model of stress-precipitated smoking behavior. For this preliminary investigation, it was hypothesized that 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin (vs. placebo) would reduce tobacco craving, increase the latency to initiate smoking, and decrease subsequent ad-libitum smoking behavior in response to stress versus neutral imagery. Based on previous findings from our laboratory that guanfacine, an α2a-adrenergic receptor agonist, normalized cortisol levels (McKee et al., 2015), we predicted that doxazosin would normalize cortisol and catecholamine levels in our sample of non-treatment seeking daily cigarette smokers. It was hypothesized that 8 mg/day doxazosin would demonstrate stronger effects than 4 mg/day doxazosin.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Design

A between-subject, double-blind, placebo-controlled design was used to compare doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) to placebo (0 mg/day). Following titration to steady-state medication levels, subjects (n=35) completed two laboratory sessions designed to model smoking-lapse behavior (stress vs. neutral imagery). Medication was tapered following completion of the two laboratory sessions.

Participants

Eligible participants were 18–60 years of age, smoked ≥10 cigarettes/day for the past year, had urine cotinine levels of ≥ 150 ng/ml, and were normotensive (sitting BP >90/60 and <160/100mmHg). Participants were excluded if they met criteria for current (past 6-month) DSM-IV Axis-1 psychiatric disorders (excluding nicotine dependence), were using illicit drugs (assessed by urine toxicology), planned to quit smoking in the next 30 days, had engaged in smoking cessation treatment in the past 6-months, had medical conditions or used concurrent medication that would contraindicate doxazosin use or smoking behavior as assessed by physical exam (including electrocardiogram and basic blood chemistries). Doxazosin use is contraindicated in patients with a hypersensitivity to doxazosin, other quinazolines (e.g., prazosin, terazosin), or any of its components (Pfizer, 2016). The study was approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were recruited from the community for a smoking laboratory study. Following the initial phone screening, 58 subjects were found eligible and 52 subjects were randomized to medication; a total of 35 subjects (4 mg/day doxazosin n=11; 8 mg/day doxazosin n=13; placebo n=11) completed the laboratory sessions.

Doxazosin Treatment

The medication condition was double-blind and placebo-controlled. Doxazosin was administered once daily and titrated to steady-state levels over 21 days (for 4 mg/day doxazosin: 1 mg daily for Days 1–4, 2 mg daily for Days 5–9, 4 mg daily for Days 10–21; for 8 mg/day doxazosin: 1 mg daily for Days 1–4, 2 mg daily for Days 5–9, 4 mg daily for Days 10–13, 6 mg daily for Days 14–17, 8 mg daily for Days 18–21). Placebos were matched in appearance and were taken on the same schedule as the active medication conditions. Medication compliance was monitored by pill counts and riboflavin marker. Following completion of the laboratory sessions, participants were tapered from medication over a 4-day period.

Adverse Events

Adverse events were assessed twice weekly during the titration period and once weekly during treatment (Levine and Schooler, 1986). Subjects were queried regarding common adverse events associated with doxazosin (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative counts and frequencies of treatment emergent adverse events commonly associated with doxazosin versus placebo during the 3-week titration period.

| Placebo (n=11) | Doxazosin 4 mg/day (n=11) | Doxazosin 8 mg/day (n=13) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event (n (%)) | |||

|

| |||

| Fatigue* | 0 (0%) | 2 (18.2%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| Headache | 3 (27.3%) | 3 (27.3%) | 5 (38.5%) |

| Dizziness | 0 (0%) | 3 (27.3%) | 2 (15.4%) |

|

| |||

| Drowsiness | 0 (0%) | 5 (45.5%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Back pain | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Chest pain | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Pain | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Fast heartbeat | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (23.1%) |

| Dry mouth | 1 (9.1%) | 3 (27.3%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Abnormal vision | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Impotence | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Increased sweating | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anxiety | 0 (0%) | 1 (9.1% | 0 (0%) |

| Insomnia | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (9.1%) | 1 (7.7%) |

All events were rated as minimal to mild on a four-point scale (1=minimal, 2=mild, 3=moderate, 4=severe).

A chi-square comparison across adverse events revealed higher incidence of fatigue during the titration period (*p < 0.05).

Laboratory Assessment of Stress-Precipitated Smoking Lapse

Procedures

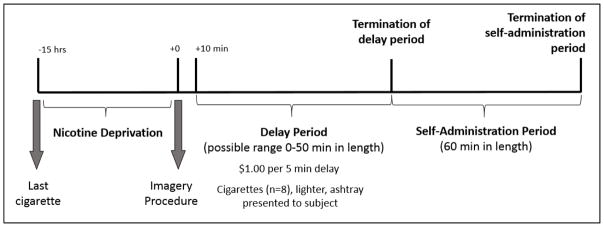

Each subject completed two 6.5-hour laboratory sessions (stress vs. neutral imagery; see Figure 1 for a Timeline of Study Procedures).

Figure 1.

Timeline of study procedures to evaluate the effect of doxazosin on the ability to resist smoking and subsequent smoking self-administration.

Baseline Assessment Period

Laboratory sessions started at 8:00am. Participants were instructed to smoke a final cigarette at 10:00pm on the previous night, which was confirmed with a CO reading of less than 50% of their baseline CO level at 8:00am the following morning (Kahler et al., 2012; Odum et al., 2002). An IV cannula was inserted to obtain blood samples. Baseline assessments of breath CO, breath alcohol, urine drug screens, urine pregnancy screen, and vital signs were obtained. Tobacco craving was also assessed. Medication administration (4 or 8 mg doxazosin or placebo) occurred at 10:00am. Participants were provided with a standardized lunch at 11:15am to control for time since last food consumption. From 10:00am to 12:30pm, subjects were able to watch television or read.

Personalized Imagery Procedure

A personalized guided imagery procedure was used to induce stress and neutral conditions. This method has demonstrated efficacy in reliably increasing smoking behavior and drug craving (McKee et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2015; Sinha, 2009). Stress imagery scripts were developed by having each participant identify and describe in detail highly stressful experiences occurring within the past 6-months. Only situations rated as 8 or higher (1=‘not at all stressful’ and 10=‘the most stress they recently felt in their life’) were accepted as appropriate for script development. A neutral script was developed from subjects’ descriptions of personal neutral or relaxing situations. Scripts were developed by a PhD-level clinician and audiotaped for presentation during the laboratory sessions. Each script was approximately 5 min in length. During the laboratory session at 12:55pm, participants listened to scripts (stress or neutral) via headphones.

Delay Period

At 1:10pm, participants were presented with a tray containing 8 cigarettes of their preferred brand, a lighter, and an ashtray. Participants were instructed that they could commence smoking at any point over the next 50 min. However, for each 5 min block of time they delayed or ‘resisted’ smoking, they would earn $1 for a maximum of $10. This amount of money was chosen based on previous studies from our laboratory that identified that the optimum level of monetary reinforcement to provide to participants while modeling the ability to resist smoking was $1 per each 5 min block of time they delayed smoking (McKee et al., 2012). Time when subjects announced they wanted to smoke (range 0–50 min) was recorded.

Smoking Self-Administration Period

The ad-libitum smoking period duration was 60 min and started once the participants decided to end the delay period (or delayed for 50 min). Thus, the delay period was terminated at the decision to smoke and the self-administration period began once the participant start to smoke the 1st of up to 8 cigarettes. Participants were instructed to ‘smoke as little or as much as you wish’. Subjects were discharged at 3:15pm.

Assessments

Primary measures included the length of the delay period (i.e., time to initiate smoking), number of cigarettes smoked during the ad-libitum smoking period, and tobacco craving (Questionnaire of Smoking Urges-Brief (Cox et al., 2001)). Other measures were collected but not included in this report. Additional measures are described below.

Cortisol, ACTH, Norepinephrine, & Epinephrine

Five mls of blood were collected at each timepoint to assess plasma cortisol, ACTH, norepinephrine and epinephrine.

Physiologic Measures

A pulse sensor was attached to the subject’s forefinger to obtain a measure of pulse rate. Blood pressure was measured using a Critikon Dynamap.

Timing of Assessments

Tobacco craving and physiologic reactivity were assessed at baseline, pre-imagery, post-imagery (prior to the presentation of cigarette cues), end of delay, and +30 min and +60 min during the ad-libitum smoking period. Cortisol, ACTH, norepinephrine and epinephrine were collected at −30, −15, +5, +20, +40, +60 min post-imagery.

Statistical Analyses

Multivariate analysis of variance was used to examine effects of medication condition by time on (week 1, week 2, week 3) on cigarettes per day, systolic BP, diastolic BP, and heart rate during the titration period. For the laboratory sessions, multivariate analysis of variance was used to examine within-subject effects of imagery condition (stress vs. neutral) by medication condition (4 mg/day doxazosin, 8 mg/day doxazosin, placebo) on the primary outcomes (i.e., length of the delay period, number of cigarettes smoked during the ad-libitum smoking period). Multivariate analyses of variance were used to examine outcomes of tobacco craving, HPA-axis reactivity, catecholamine levels, and physiologic reactivity within imagery condition (stress vs. neutral), within time (pre-imagery, post-imagery), and by medication condition (4 mg/day doxazosin, 8 mg/day doxazosin, placebo). The post-imagery timepoint occurred prior to the start of the smoking lapse task. If outcomes differed by medication at the baseline timepoint, the GLM was conducted with the baseline values included as a covariate. According to the predefined analytical plan, age, sex, baseline cigarettes per day, FTND scores, and CES-D scores were also evaluated as covariates (or as a between-subject variable in the case of sex), and were retained if they reduced residual variance, or were otherwise excluded. Planned contrasts examined 4 mg/day versus placebo, 8 mg/day versus placebo, and 4 mg/day versus 8 mg/day. Doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) was collapsed across medication dose if there were not significant differences between medication groups. A manipulation-check of the blind was assessed using chi-square to determine if participants were correctly able to identify their medication condition.

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) and placebo groups were well-matched for baseline demographics. All baseline comparisons across medication conditions were not significant (p > 0.05), except for FTND scores (p = 0.02, placebo > 4 mg/day doxazosin; see Table 1). FTND was evaluated as a covariate in all subsequent analysis. Mean CO levels at the start of the laboratory sessions (8:00am) were 16.83 (SE=2.23) and 15.54 (SE=1.97) for the stress and neutral imagery conditions, respectively, and values did not differ by medication.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by medication condition.

| Mean, SD or n, % | Placebo (n=11) | 4 mg/day Doxazosin (n=11) | 8 mg/day Doxazosin (n=13) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||

| Baseline | |||

|

|

|

||

| Age | 37.36, 9.29 | 34.82, 10.85 | 34.23, 9.83 |

| Gender (male) | 8, 72.7% | 7, 63.6% | 9, 69.2% |

| Race (Caucasian) | 6, 54.5% | 6, 54.5% | 4, 30.8% |

| Education (≤ high school) | 9, 81.8% | 4, 36.4% | 9, 69.2% |

| Income | |||

| Less than $19,999 | 6, 54.5% | 6, 54.5% | 6, 46.2% |

| $20,000-$39,999 | 1, 9.1% | 2, 18.2% | 2, 15.4% |

| Over $40,000 | 4, 36.4% | 2, 18.2% | 4, 30.8% |

| Cigarettes per day | 18.55, 6.77 | 13.00, 6.07 | 16.23, 12.52 |

| FTNDa* | 6.00, 2.10 | 3.36, 2.20 | 4.85, 1.82 |

| CO levels at intake | 32.09, 29.41 | 29.36, 22.62 | 32.46, 30.15 |

All baseline comparisons across medication conditions were not significant (p > 0.05), except FTND (p = 0.02; placebo > 4 mg/day doxazosin).

Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence, FTND (Heatherton et al., 1991), range 1–10 for measure.

Adverse Events

All adverse events were rated as minimal to mild, and no subject discontinued treatment or required a dose adjustment due to adverse events (see Table 2).

Titration Phase: Exploratory Findings

Doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) significantly decreased the number of cigarettes smoked per day during the titration period (mean (SE) cigarettes per day: placebo 14.83 (0.33), 4 mg/day 13.56 (0.35), 8 mg/day 13.51 (0.30); main effect of medication: F(2,30) = 5.15, p = 0.01; Cohen’s d=0.83). Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate did not significantly change by medication condition during the titration period.

Laboratory Sessions: Tobacco Craving, Latency to Smoke, and Ad-libitum Smoking

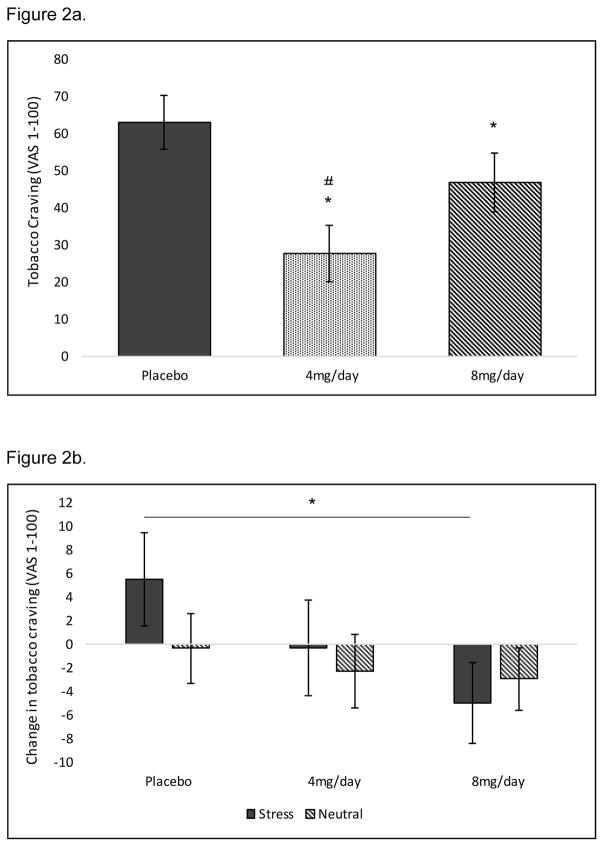

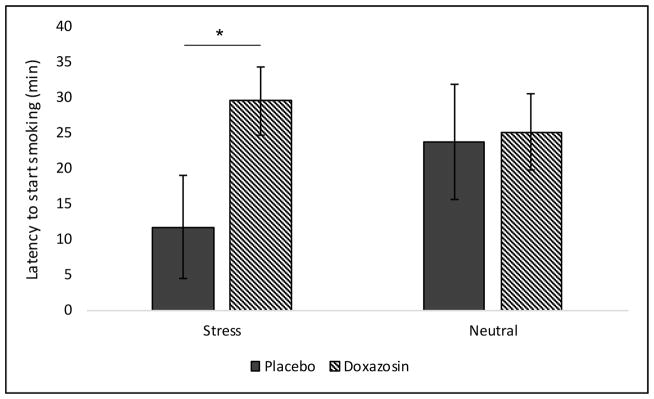

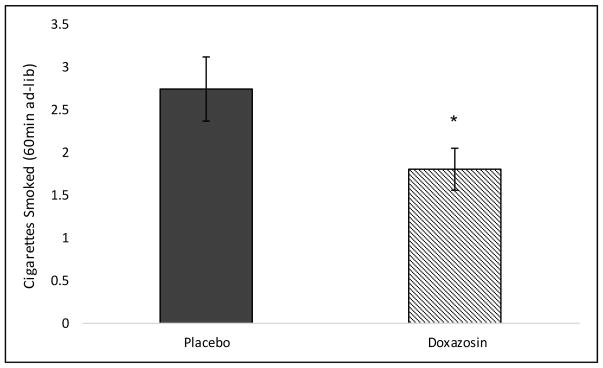

At the baseline timepoint (8am), 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin significantly decreased tobacco craving (see Figure 2a). When examining changes in tobacco craving from pre- to post-imagery, 8 mg/day doxazosin decreased tobacco craving following stress imagery relative to placebo (medication by imagery by time interaction: F(2,26) = 4.56, p = 0.02; Cohen’s d=0.84; see Figure 2b). For latency to smoke, doxazosin (collapsed across medication) increased the latency to start smoking in the stress versus neutral imagery condition only (medication by imagery interaction: F(1,32) = 4.57, p = 0.04; Cohen’s d=0.76; see Figure 3). Once subjects started smoking, doxazosin (collapsed across medication) decreased the number of cigarettes smoked during the 60-minute ad-libitum smoking period relative to placebo (main effect of medication: F(1,30) = 4.01, p = 0.05; Cohen’s d=0.73; see Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Baseline differences collapsed across stress and neutral imagery conditions for mean (±SE) subjective tobacco craving ratings (a). Effect of medication (4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin vs. placebo) and imagery (stress vs. neutral) on change (pre- to post-imagery) in tobacco craving ratings during the smoking-lapse paradigm (b). NOTE: The post-imagery timepoint occurs prior to smoking. *Doxazosin significantly different vs. placebo; #4 mg/day doxazosin significantly different vs. 8 mg/day doxazosin.

Figure 3.

Mean (± SE) latency to initiate smoking (min) by imagery condition (stress vs. neutral) by medication. *Doxazosin significantly different vs. placebo.

Figure 4.

Mean (± SE) cigarettes smoked during the 60-minute ad-libitum smoking period during the smoking-lapse task. Doxazosin was collapsed across medication because 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin did not differ by medication. *Doxazosin significantly different vs. placebo.

Cortisol, ACTH, Norepinephrine, and Epinephrine

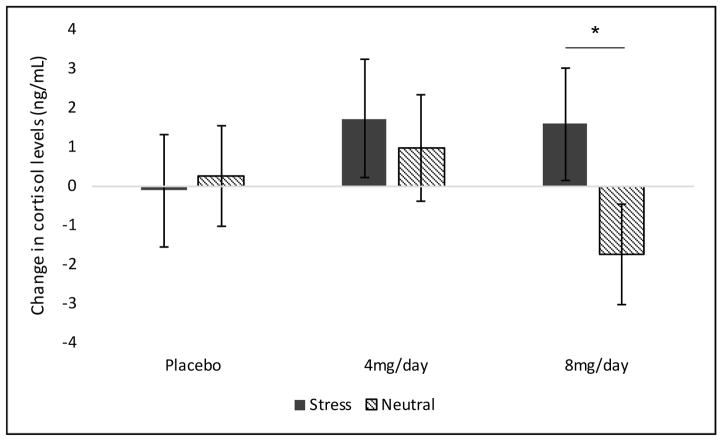

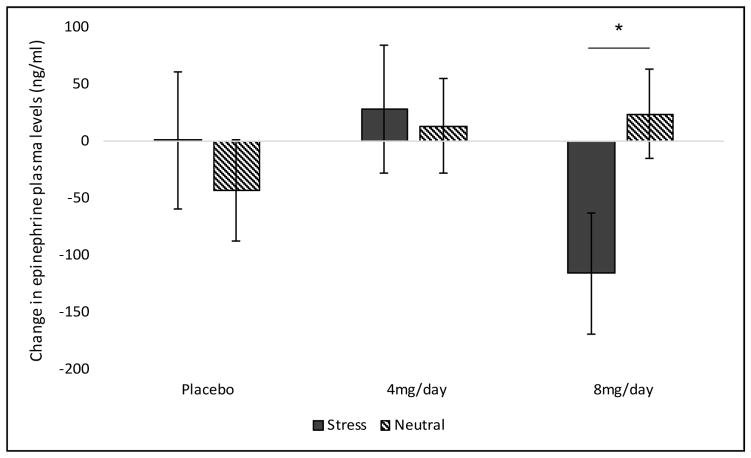

For cortisol levels, a priori contrasts comparing 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin to placebo demonstrated that 8 mg/day doxazosin increased cortisol levels following stress imagery and decreased cortisol levels following neutral imagery (F(1,18) = 3.03, p < 0.05; Cohen’s d=0.82; see Figure 5). ACTH levels did not demonstrate significant effects of medication or imagery condition. For epinephrine, 8 mg/day doxazosin attenuated increases in epinephrine levels in the stress versus neutral imagery condition (medication by imagery by time interaction: F(2,21) = 6.01, p = 0.01; Cohen’s d=1.07; see Figure 6). Norepinephrine plasma levels did not demonstrate significant effects of medication or imagery condition.

Figure 5.

Effect of medication (4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin, placebo) and imagery (stress vs. neutral) on cortisol levels during the smoking-lapse paradigm. A-prori contrasts of change (pre- to post-imagery) demonstrated that cortisol levels differed by medication group by imagery condition (p < 0.05). NOTE: The post-imagery timepoint occurs prior to smoking. *Stress significantly different vs. neutral imagery in the 8 mg/day doxazosin group.

Figure 6.

Effect of medication (4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin vs. placebo) and imagery (stress vs. neutral) on change (pre- to post-imagery) in epinephrine plasma levels (ng/ml) during the smoking-lapse paradigm (b). NOTE: The post-imagery timepoint occurs prior to smoking. *Stress significantly different vs. neutral imagery in the 8 mg/day doxazosin group.

Physiologic Measures

Systolic blood pressure increased from pre- to post-imagery in the placebo versus doxazosin group (collapsed across medication), and doxazosin decreased this effect post-imagery (medication by time interaction: F(1,33) = 4.32, p = 0.05; Cohen’s d=0.72; see Figure 7a). For diastolic blood pressure, 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin attenuated diastolic blood pressure in the stress versus neutral imagery condition relative to placebo (medication by imagery interaction: F(2,30) = 3.62, p = 0.04; Cohen’s d=0.69; see Figure 7b). For heart rate, doxazosin (collapsed across medication) increased heart rate (main effect of medication: F(1,33) = 6.09, p = 0.02; Cohen’s d=0.86; see Figure 7c).

Figure 7.

Effect of medication (doxazosin vs. placebo) on change (pre- to post-imagery) in systolic blood pressure (a), mean (±SE) diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) by imagery condition (stress vs. neutral) by medication (b), mean (±SE) heart rate (bpm) by medication (c) during the smoking-lapse paradigm. Doxazosin was collapsed across medication for systolic blood pressure and heart rate because 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin did not differ by medication. *Doxazosin significantly different vs. placebo.

Manipulation-Check of the Medication Blind

There was no significant difference in the ability of participants in the placebo or doxazosin groups to correctly identify their medication treatment condition (p=0.94). 40% correctly identified their medication treatment condition while 51% incorrectly identified their medication treatment condition (3 participants did not respond).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first preliminary investigation examining the effect of doxazosin (4 and 8 mg/day) on stress-precipitated smoking in nicotine-deprived daily cigarette smokers. Results suggest that doxazosin reduced stress-precipitated smoking lapse by increasing the latency to initiate smoking, attenuating stress-induced increases in tobacco craving, and decreasing subsequent ad-libitum smoking in the human laboratory. Prior to the smoking-lapse task, 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin decreased tonic levels of tobacco craving. When these baseline medication differences were accounted for in the analysis, only 8 mg/day doxazosin continued to reduce stress-related increases in tobacco craving.

Our results are consistent with prior findings (McKee et al., 2011) demonstrating a reduced ability to resist smoking following stress using the same validated human laboratory model of smoking-lapse behavior (McKee et al., 2012). We demonstrated that personalized stress imagery decreased the ability to resist smoking, or the time to initiate smoking, and increased tobacco craving. Doxazosin attenuated the effect of stress on latency to initiate smoking and craving, and decreased ad-libitum smoking. These findings extend preclinical findings that α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists attenuate reinstatement of nicotine-seeking and self-administration (Forget et al., 2010), and reduce stress-induced reinstatement and self-administration of other drugs of abuse (Greenwell et al., 2009; Le et al., 2011; O’Neil et al., 2013; Verplaetse et al., 2012; Verplaetse and Czachowski, 2015). Our results also extend human findings demonstrating that doxazosin reduced alcohol and cocaine use outcomes in alcohol and cocaine dependent individuals, respectively (Kenna et al., 2016; Newton et al., 2012; Shorter et al., 2013).

Our findings demonstrate stress-precipitated changes in cortisol levels such that placebo-treated subjects demonstrated reductions in cortisol levels in response to stress, whereas doxazosin-treated subjects demonstrated increased cortisol levels. This is consistent with clinical findings that smokers demonstrate blunted hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity in response to stress compared to non-smokers (al’Absi et al., 2003), and this attenuated response to stress has been associated with shorter times to smoking relapse (al’Absi et al., 2005). These findings suggest that doxazosin may work to normalize the cortisol response to stress in nicotine-deprived daily smokers. To a similar effect, doxazosin-treated subjects compared to placebo-treated subjects demonstrated increased norepinephrine and epinephrine levels overall. Previous findings demonstrate that chronic smoking may down-regulate noradrenergic autoreceptors in the locus coeruleus (Klimek et al., 2001), a nucleus comprised primarily of norepinephrine-containing neurons. Thus, doxazosin may also work to normalize blunted catecholamine release in chronic smokers. There were no significant effects of medication or imagery condition on ACTH levels.

During the titration period, exploratory analyses demonstrated that 4 and 8 mg/day doxazosin versus placebo significantly reduced cigarettes per day during each of the 3 weeks prior to the first laboratory session. Doxazosin also tended to reduce diastolic blood pressure during the 2 weeks prior to the first laboratory session, but had no effect on systolic blood pressure or heart rate. During the laboratory sessions, doxazosin reduced the effect of stress on diastolic blood pressure and reduced systolic blood pressure post-imagery, but increased heart rate across stress and neutral imagery conditions and time. As doxazosin levels are reaching maximal concentration following dosing, effects on blood pressure are maximized and this is also associated with small increases in heart rate (https://www.drugs.com/pro/doxazosin.html). Overall, the effects of doxazosin on physiologic reactivity during the titration period and laboratory sessions suggest that doxazosin reduces elevations in blood pressure, and has some effects on attenuating stress-related increases in physiologic reactivity. The effect of doxazosin on cigarettes per day during the titration period suggests that doxazosin may be effective within the first week of medication initiation.

Doxazosin was well-tolerated in our sample of non-treatment seeking daily smokers. Mean severity ratings for each adverse event were reported as minimal to mild. There was only one difference in frequency ratings of adverse events during the titration period (see Table 2). Rates of fatigue were greatest in the 8 mg/day doxazosin treatment condition (0% placebo, 18.2% 4 mg/day doxazosin, 30.8% 8 mg/day doxazosin). Further, no subject discontinued medication or required a dose adjustment as a result of adverse events. Overall, our findings suggest that doxazosin appears to be safe and well-tolerated in daily cigarette smokers.

The noradrenergic system contains three classes of receptors, α1, α2, and β. While the present investigation found that doxazosin, an α1-adrenergic antagonist, decreased tobacco craving, increased the ability to resist smoking, and reduced ad-libitum smoking following stress, a recent study from our group demonstrated similar effects of guanfacine, an α2a-adrenergic agonist, using the same human laboratory analogue of stress-precipitated smoking-lapse behavior. In that study, guanfacine also decreased tobacco craving, increased the latency to start smoking (or the ability to resist smoking), and decreased subsequent smoking self-administration following a personalized stress imagery script (McKee et al., 2015). Similarly, both studies demonstrated increased cortisol levels in response to stress in each medication-treated group versus placebo. Thus, noradrenergic medications spanning the α1 and α2 receptor classes and that reduce noradrenergic activity may work to attenuate smoking-lapse behavior and normalize stress reactivity in nicotine-deprived daily smokers. This work supports the notion that noradrenergic pathways are involved in stress-precipitated smoking, and that their manipulation may be of pharmacotherapeutic benefit for smoking cessation. Future work should examine the effects of β-adrenergic antagonists on stress-precipitated smoking-lapse behavior, particularly in light of preclinical work suggesting that propranolol reduces the somatic signs associated with nicotine withdrawal in Wistar rats (Bruijnzeel et al., 2010). Additionally, future work should examine gender-sensitive mechanisms by which doxazosin may affect smoking behavior. This is particularly important in light of evidence from our laboratory and others that smoking activates different brain systems modulated by the noradrenergic system in women versus men (Verplaetse et al., 2015).

There are some limitations to the present investigation. This study had a modest sample size of 35 daily smokers. While the sample size is comparable to other human laboratory studies and doxazosin demonstrated effects on our primary outcomes, we consider these outcomes to be preliminary and it will be important to replicate findings. Second, this sample of nicotine-deprived daily smokers were non-treatment seeking. The results may not generalize to treatment seeking daily smokers or individuals who are not nicotine deprived. However, doxazosin was effective in reducing cigarettes per day during the titration period when subjects were not nicotine-deprived. Third, baseline comparisons between medication conditions revealed higher FTND scores in the placebo group versus the 4 mg/day doxazosin group. This baseline difference may have affected outcomes relating to tobacco craving, latency to smoke, and ad-libitum smoking behavior. However, FTND was evaluated as a covariate in all analyses. Finally, as all participants received the same instructions regarding random medication assignment and medication side effects, we were unable to evaluate whether there was differential reactivity to these instructions.

Overall, our preliminary results provide promising evidence for the use of doxazosin for smoking cessation, and clinical trial investigations should be pursued in order to evaluate the efficacy of doxazosin in treatment seekers. Using a well-validated human laboratory analogue of stress-precipitated smoking, we report for the first time that doxazosin increased the ability to resist smoking, decreased subsequent ad-libitum smoking, reduced tobacco craving, and normalized the cortisol response to stress in nicotine-deprived smokers. Our findings are consistent preclinical and clinical results that α1-adrenergic receptor antagonists reduce stress-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking and self-administration behavior, as well as drug craving. These data further support the clinical utility of doxazosin as a novel pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation and stress-related relapse.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Supported by NIH grants R21DA033597, P50DA033945, R01AA017976, R01MH077681, UL1TR001863, and T32DA007238.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

Sherry A. McKee has consulted to Cerecor and Embera, has received research support for investigator-initiated studies from Pfizer, Inc. and Cerecor, and has ownership in Lumme, Inc. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Akduman B, Crawford ED. Terazosin, doxazosin, and prazosin: current clinical experience. Urology. 2001;58(6):49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01302-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Erickson J, et al. Attenuated adrenocortical and blood pressure responses to psychological stress in ad libitum and abstinent smokers. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2003;74(2):401–410. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181(1):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijnzeel AW, Bishnoi M, van Tuijl IA, et al. Effects of prazosin, clonidine, and propranolol on the elevations in brain reward thresholds and somatic signs associated with nicotine withdrawal in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212(4):485–499. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1970-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality—beyond established causes. New England journal of medicine. 2015;372(7):631–640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1407211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3(1):7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott H, Meredith P, Vincent J, et al. Clinical pharmacological studies with doxazosin. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1986;21(S1):27S–31S. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1986.tb02850.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, Ghee SM, See RE. Nicotine self-administration and reinstatement of nicotine-seeking in male and female rats. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012;121(3):240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Jaen CR, Baker T, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Forget B, Wertheim C, Mascia P, et al. Noradrenergic alpha1 receptors as a novel target for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(8):1751–1760. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay SG, Stead LF, Benowitz NL. Clonidine for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD000058. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000058.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwell TN, Walker BM, Cottone P, et al. The alpha1 adrenergic receptor antagonist prazosin reduces heroin self-administration in rats with extended access to heroin administration. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;91(3):295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grella SL, Funk D, Coen K, et al. Role of the kappa-opioid receptor system in stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2014;265:188–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(47):1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby D, Hays J, Rigotti N, et al. Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group: Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):56–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Metrik J, Spillane NS, et al. Sex differences in stimulus expectancy and pharmacologic effects of a moderate dose of alcohol on smoking lapse risk in a laboratory analogue study. Psychopharmacology. 2012;222(1):71–80. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenna GA, Haass-Koffler CL, Zywiak WH, et al. Role of the alpha1 blocker doxazosin in alcoholism: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Addict Biol. 2016;21(4):904–914. doi: 10.1111/adb.12275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimek V, Zhu MY, Dilley G, et al. Effects of long-term cigarette smoking on the human locus coeruleus. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):821–827. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Funk D, Juzytsch W, et al. Effect of prazosin and guanfacine on stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol and food seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218(1):89–99. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2178-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine J, Schooler N. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacology bulletin. 1986;22(2):343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Zou S, Coen K, et al. Sex differences in yohimbine-induced increases in the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in adolescent rats. Addict Biol. 2014;19(2):156–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2012.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Maciejewski PK, Falba T, et al. Sex differences in the effects of stressful life events on changes in smoking status. Addiction. 2003;98(6):847–855. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Potenza MN, Kober H, et al. A translational investigation targeting stress-reactivity and prefrontal cognitive control with guanfacine for smoking cessation. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(3):300–311. doi: 10.1177/0269881114562091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Sinha R, Weinberger AH, et al. Stress decreases the ability to resist smoking and potentiates smoking intensity and reward. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25(4):490–502. doi: 10.1177/0269881110376694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee SA, Weinberger AH, Shi J, et al. Developing and validating a human laboratory model to screen medications for smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14(11):1362–1371. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, De La Garza R, 2nd, Brown G, et al. Noradrenergic alpha(1) receptor antagonist treatment attenuates positive subjective effects of cocaine in humans: a randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e30854. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil ML, Beckwith LE, Kincaid CL, et al. The alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, doxazosin, reduces alcohol drinking in alcohol-preferring (P) Rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37(2):202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01884.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Discounting of delayed health gains and losses by current, never-and ex-smokers of cigarettes. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4(3):295–303. doi: 10.1080/14622200210141257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer. Cardura-doxazosin mesylate tablet. 2016 Available at: http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=538.

- Shorter D, Lindsay JA, Kosten TR. The alpha-1 adrenergic antagonist doxazosin for treatment of cocaine dependence: A pilot study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1–2):66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R. Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addict Biol. 2009;14(1):84–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Babb D, Hatsukami DK. Labetalol treatment enhances the attenuation of tobacco withdrawal symptoms by nicotine in abstinent smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5(6):947–953. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001615312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sofuoglu M, Mouratidis M, Yoo S, et al. Adrenergic blocker carvedilol attenuates the cardiovascular and aversive effects of nicotine in abstinent smokers. Behavioural pharmacology. 2006;17(8):731–735. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32801155d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, Czachowski CL. Low-dose prazosin alone and in combination with propranolol or naltrexone: effects on ethanol and sucrose seeking and self-administration in the P rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2015;232(15):2647–2657. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3896-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, Rasmussen DD, Froehlich JC, et al. Effects of prazosin, an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist, on the seeking and intake of alcohol and sucrose in alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(5):881–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01653.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse TL, Weinberger AH, Smith PH, et al. Targeting the noradrenergic system for gender-sensitive medication development for tobacco dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(4):486–495. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villegier AS, Lotfipour S, Belluzzi JD, et al. Involvement of alpha1-adrenergic receptors in tranylcypromine enhancement of nicotine self-administration in rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193(4):457–465. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0799-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Report: Mortality Attributable to Tobacco. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada H, Bruijnzeel AW. Stimulation of alpha2-adrenergic receptors in the central nucleus of the amygdala attenuates stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine seeking in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60(2–3):303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zislis G, Desai TV, Prado M, et al. Effects of the CRF receptor antagonist D-Phe CRF(12–41) and the alpha2-adrenergic receptor agonist clonidine on stress-induced reinstatement of nicotine-seeking behavior in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53(8):958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]