Abstract

BACKGROUND

Storage and transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) has a huge medical and economic impact. Routine storage practices can be ameliorated through the implementation of novel additive solutions (ASs) that tackle the accumulation of biochemical and morphologic lesion during routine cold liquid storage in the blood bank, such as the recently introduced alkaline solution AS-7. Here we hypothesize that AS-7 might exert its beneficial effects through metabolic modulation during routine storage.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

Apheresis RBCs were resuspended either in control AS-3 or experimental AS-7, before ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry metabolomics analysis.

RESULTS

Unambiguous assignment and relative quantitation was achieved for 229 metabolites. AS-3 and AS-7 results in many similar metabolic trends over storage, with AS-7 RBCs being more metabolically active in the first storage week. AS-7 units had faster fueling of the pentose phosphate pathway, higher total glutathione pools, and increased flux through glycolysis as indicated by higher levels of pathway intermediates. Metabolite differences are especially observed at 7 days of storage, but were still maintained throughout 42 days.

CONCLUSION

AS-7 formulation (chloride free and bicarbonate loading) appears to improve energy and redox metabolism in stored RBCs in the early storage period, and the differences, though diminished, are still appreciable by Day 42. Energy metabolism and free fatty acids should be investigated as potentially important determinants for preservation of RBC structure and function. Future studies will be aimed at identifying metabolites that correlate with in vitro and in vivo circulation times.

The collection and storage of red blood cells (RBCs) is a logistical necessity to provide sufficient blood products that enable lifesaving therapies to approximately 5 million Americans every year.1 However, decades of biochemical and, most recently, omics (proteomics, metabolomics) investigations have highlighted that routine storage in the blood bank results in the progressive accumulation of a wide series of biochemical alterations, collectively referred to as the “storage lesion.”1,2 Even though the clinical relevance of such lesions has yet to be assessed,1 laboratory investigations have documented a long series of storage-dependent alterations, including but not limited to RBC morphology, physiology (gas transport and offloading-related variables), osmotic fragility, energy, redox and lipid metabolism, membrane proteomics profiles (especially involving Band 3), release of vesicles, and proinflammatory mediators in the supernatants,3 as extensively reviewed.2

While early results from ongoing prospective clinical trials suggest little or no correlation between storage duration and untoward transfusion-related consequences,4–6 concerns still arise and persist that such a lesion might compromise safety and efficacy of the transfusion therapy.1 Despite the lack of definitive prospective clinical evidence, which probably will not be delivered by ongoing studies owing to controversial study design limitations,1 efforts to improve RBC storage quality by testing alternative storage strategies or alternative additive solutions (ASs) have constantly been under way.7–11

In recent years, metabolomics technologies have emerged as a promising tool in the field of RBC processing and biopreservation.2,10 Applications span from the appreciation of RBC metabolic lesions during routine storage in the presence of different ASs,3,12–15 to testing of alternative storage solutions (e.g., supplementation of antioxidants, vitamin C, or N-acetylcysteine8,9) or strategies (such as anaerobic storage16). Metabolomics has been also used as a readout of biochemical lesions resulting from pathogen inactivation treatments to stored units17 and to investigate the heritability and strain specificity of metabolic markers of RBC storage quality in humans18,19 and mice,20 respectively.

These strides in the field of metabolomics technologies mainly result from the introduction of ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) separations coupled online with faster scanning and more sensitive and resolved mass spectrometer instruments, other than from the expansion and curation of publicly accessible metabolome databases (Metlin, KEGG, HMDB) and availability of high-throughput data mining software.21,22 Besides, RBC metabolic networks might be more complex than previously anticipated, as predicted by in silico models23 based on proteomics and interactomics data.24

Metabolomics investigation of RBC lesion during storage in the blood bank have recently highlighted common and unique patterns depending on the AS in which RBCs are stored, AS-1,15 AS-3,25 or AS526 in the United States or SAGM,12,27 MAP,13 and PAGGGM14,28 in Europe and other countries. In this respect, encouraging results have been observed when storing RBCs in presence of alkaline solutions such as AS-7,29–31 previously known as EAS-81.32

Alkaline ASs (such as AS-732 or PAGGGM18) have been designed to promote glycolytic enzyme activities (especially phosphofructokinase18) by mitigating pH-dependent negative feedbacks on glycolytic fluxes during routine storage in the blood bank.32 In so doing, AS-7 has been demonstrated to promote energy metabolism to improve preservation of high-energy phosphate compounds 2,3-diphosphoglycerate (DPG) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP),29 pivotal molecules participating in RBC energy homeostasis, cation pump activity, membrane stability and gas transport physiology, and contributing to allosteric modulation of hemoglobin (Hb). This is relevant in that these compounds are rapidly consumed during storage in the blood bank, and preservation of ATP and DPG reservoirs is deemed to influence RBC survival upon transfusion.1,2 The levels and storability of these compounds are donor-dependent factors18 and indirectly affect redox metabolism since glutathione (GSH) biosynthesis is an ATP-dependent process.

Omics technologies10 and in silico elaborations of metabolomics data23 hold the potential to guide the design and testing of novel ASs, to improve storage quality and extend the shelf life of RBCs. While future studies will be aimed at producing correlative evidence of omics results with clinically relevant outcomes such as hemolysis19 and 24-hour in vivo survival, here we test the hypothesis that AS-7 preserves RBC metabolic homeostasis better than AS-3, resulting in more metabolically active RBCs throughout storage duration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Blood processing and sample collection

We conducted an unpaired single center pilot evaluation of the AS-7 RBC AS (Haemonetics Corp., Braintree, MA) compared to the AS-3 (Nutricel, Haemonetics Corp.). Briefly, RBCs (180–210 mL) were collected by apheresis (MCS+ 8150, Haemonetics Corp.) from healthy research subjects (n =10) using standard methods into either CP2D (n =5) or CPD (n =5). The appropriate AS was added to the RBC by the apheresis device (AS-3 to CP2D RBC and AS-7 to CPD RBC). RBC units were then leukoreduced by filtration at room temperature (BPF4, Haemonetics Corp.). Units were then divided into 150 mL DEHP-PVC and distributed to three other laboratories for testing not reported here, and one bag was retained in the collection facility. The RBC units were placed at 1 to 6°C within 8 hours of collection and held for 42 days. Aliquots (0.5 mL) for metabolomic analysis were removed on Days 0, 7, and 42, frozen at −80°C, and shipped to the metabolomics laboratory on dry ice for analysis.

This study was conducted following approval by the FDA under an investigational new drug application, the local institutional review board. All subjects provided informed consent for participation. This study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Metabolomics extraction

RBCs were immediately extracted at 1:6 dilutions (100 μL in 500 μL) in ice-cold lysis and extraction buffer (methanol:acetonitrile:water 5:3:2). Samples were then agitated at 4°C for 30 minutes and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. Protein- and non–methanol-soluble lipid pellets were discarded, while supernatants were stored at −80°C before metabolomics analyses.

Metabolomics analysis

Metabolomics analyses were performed as previously reported,25,33 with minor modifications. Ten microliters of sample extracts was injected into an UPLC system (Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) and run on a XB-C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm i.d., 1.7 μm particle size, Kinetex, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) using either a 3-minute isocratic flow at 250 μL/min (mobile phase—5% acetonitrile, 95% 18 mΩ H2O, 0.1% formic acid) or a 9-minute gradient from 5 to 95% organic solvent B (mobile phases—A =18 mΩ H2O, 0.1% formic acid; B = methanol, 0.1% formic acid). The UPLC system was coupled online with a hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (Q Exactive system, Thermo Fisher Scientific), scanning in full mass spectrometry (MS) mode (3-min method) or performing acquisition-independent fragmentation (AIF-MS/MS analysis, 9-min method) at 70,000 resolution in the 60 to 900 m/z range, 4-kV spray voltage, 15 sheath gas, and 5 auxiliary gas, operated in negative and then positive ion mode (separate runs). Calibration was performed before each analysis against positive or negative ion mode calibration mixes (Piercenet-Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL) to ensure sub-ppm error of the intact mass. Metabolite assignments were performed using computer software (Maven,21 Princeton, NJ), upon conversion of .raw files into .mzXML format through MassMatrix (Cleveland, OH). The software allows for peak picking, feature detection, and metabolite assignment against the KEGG pathway database. Assignments were further confirmed against chemical formula determination (as gleaned from isotopic patterns and accurate intact mass) and retention times against a subset of standards including commercially available glycolytic and Krebs cycle intermediates, amino acids, GSH homeostasis, and nucleoside phosphates (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). When necessary, structural isomer ambiguous assignments were validated by comparing MS/MS data against available small molecule fragmentation databases (Metlin, RAMClust) or available standards. Relative quantitation was performed by exporting integrated peak areas values into a computer database (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) for statistical analysis including two-tailed t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA; significance threshold for p values < 0.05), totally unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA), and partially supervised partial least square discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), sorting by storage day, donor, or after the first two elaborations, tentative ASs. PCA and PLS-DA were calculated through the macro MultiBase (freely available at www.NumericalDynamics.com).

Hierarchical clustering analysis (HCA) was performed through the computer software (GENE-E, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA). Figure panels were assembled through Photoshop CS5 (Adobe, Mountain View, CA).

RESULTS

A total of 10 RBC units (5 in AS-3 vs. 5 in AS-7) were collected through apheresis and sampled on Storage Days 0, 7, and 42 (Table 1). The final volume of leukoreduced RBC units with AS before dividing were 363 ± 22 mL for AS-3 units and 385 ± 21 for AS-7 units (Table 1). Portions stored in 150-mL transfer packs were 63.1 ± 2.5 mL (AS-3) and 70.1 ± 8.6 (AS-7). No differences were observed in the RBC indices between AS groups. Consistent with previous reports, the effect of higher osmotic AS-3 (462 mOsm) compared to AS-7 (237 mOsm) is seen in the lower spun hematocrit (Hct) levels for AS-3 units. This is due to cell shrinkage in the hyperosmotic AS-3. This effect is not observed in the automated mean cell (RBC) volume (MCV) measurements since the automated system performs large dilutions with isotonic solutions and the cell volume has time to respond before passing the detectors in the hematology analyzer.

TABLE 1.

RBC indices (mean ± SD)

| Day | Volume (mL) | RBC (×1012/L) | Hb (g/dL) | Spun Hct (%) | MCV (fL) | MCH (pg) | MCHC (g/dL) | pH (22°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||||||||

| AS-3 | 364 ± 22 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 59.8 ± 3.0 | 91.4 ± 5.2 | 30.9 ± 1.5 | 33.8 ± 1.8 | 7.18 ± 0.12 |

| AS-7 | 385 ± 21 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 18.6 ± 1.1 | 62.2 ± 2.4 | 89.1 ± 4.4 | 30.5 ± 1.2 | 34.2 ± 1.2 | 7.35 ± 0.13 |

| 7 | ||||||||

| AS-3 | 63.1 ± 2.5 | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 18.4 ± 1.2 | 57.8 ± 2.3 | 88.4 ± 2.8 | 30.6 ± 1.7 | 34.7 ± 2.1 | |

| AS-7 | 70.1 ± 8.6 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 18.6 ± 1.1 | 59.4 ± 2.2 | 84.2 ± 2.9 | 30.4 ± 0.7 | 36.2 ± 1.0 | |

| 42 | ||||||||

| AS-3 | 40.7 ± 5.0 | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 18.2 ± 1.1 | 57.7 ± 1.8 | 95.2 ± 4.4 | 30.9 ± 1.7 | 32.5 ± 1.3 | 6.6 ± 0.0 |

| AS-7 | 46.3 ± 8.2 | 6.1 ± 0.4 | 18.5 ± 1.0 | 58.6 ± 1.7 | 90.0 ± 2.3 | 30.4 ± 1.1 | 33.7 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.1 |

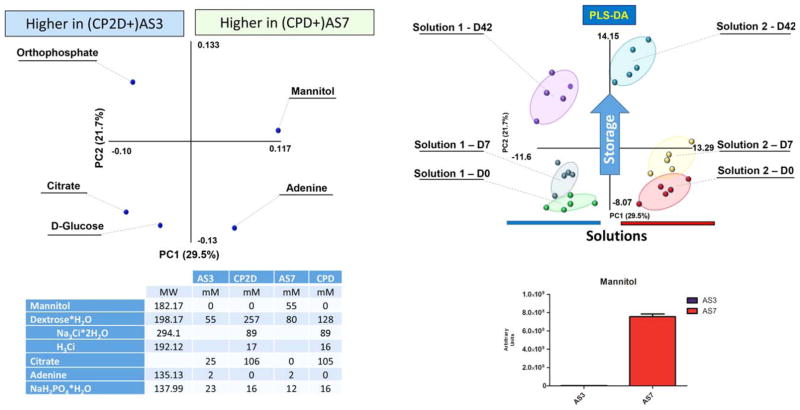

The complete metabolomic analyses AS-3 and AS-7 RBC extracts, which include compound names, KEGG pathway IDs, pathway assignments (color code explained in the legend at the end of each table), mass-to-charge ratios (m/z =parent), median retention times, median values for each time point, sparkline graphs indicating trends at a glance, the polarity mode (either positive or negative) in which the metabolite has been detected were comprehensively reported (Table S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper). Unambiguous assignment and relative quantitation was achieved for 229 metabolites in RBC extracts. Mannitol, which is present in AS-7 and absent in AS-3, clearly discriminated the two groups (Fig. S1, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper). To further validate the metabolomics approach, clustering of metabolic profiles for RBC extracts was obtained through unsupervised PCA (Table S1) and informed subsequent partially supervised PLS-DA (Fig. 1). PLS-DA allowed discrimination of storage time points along PC2 and of the two different ASs along PC1 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PLS-DA discriminates between AS-3 and AS-7 samples on Storage Days (D) 0, 7, and 42. The loading plot in the left-hand side of the figure shows the distribution of AS components that were detected through UPLC-MS metabolomics analyses around PCs 1 and 2. Unsupervised principal component analyses informed PLS-DA that highlights the presence of six clusters in the right-hand side of the figure. The clusters were later identified according to storage time (along PC2) and AS (along PC2). On the basis of the loading plot (variable distribution, also including mannitol—present in AS-7 but not in AS-3), ASs could be discriminated.

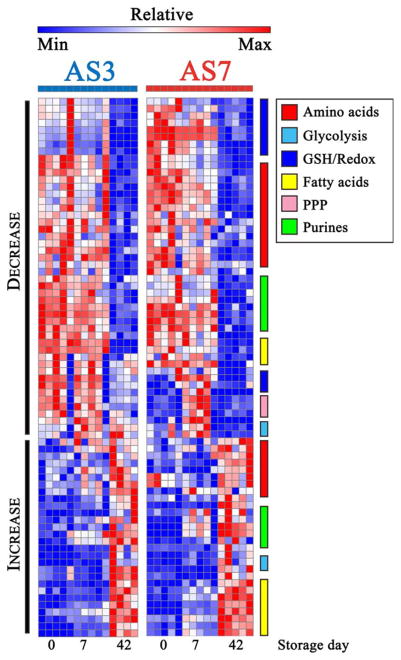

HCA through heat maps further confirmed the PLS-DA output and highlight similar trends between the two ASs for metabolite decreasing or increasing during storage (Fig. 2). However, AS-7–specific trends were observed on Storage Day 7 in energy and redox metabolism that are illustrated through quantitative color-coded changes from Storage Day 0 to Storage Day 7 and Storage Day 42 (Fig. 2; heat maps are also provided in Fig. S2, available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, in a vectorial format, also including clustering layouts and metabolite names). Figures 3 to 6 provide an overview of the quantitative trends for metabolites of glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), one-carbon metabolism, GSH homeostasis, amino acids, arginine, and purine metabolism.

Fig. 2.

HCA of metabolite levels during storage in AS-3 and AS-7. HCA showed consistent trends for AS-3 and AS-7 samples for metabolites involved in the same key metabolic pathways. Relative values (Z-score normalized) for AS-3 and AS-7 samples are color-coded from blue to red (low to high). Peculiar transient increases in metabolites involved in glycolysis, PPP, and GSH and redox homeostasis were observed in AS-7 samples, highlighting peculiar phenotypes. Full metabolite and sample names are provided in Fig. S2 in a vectorial format.

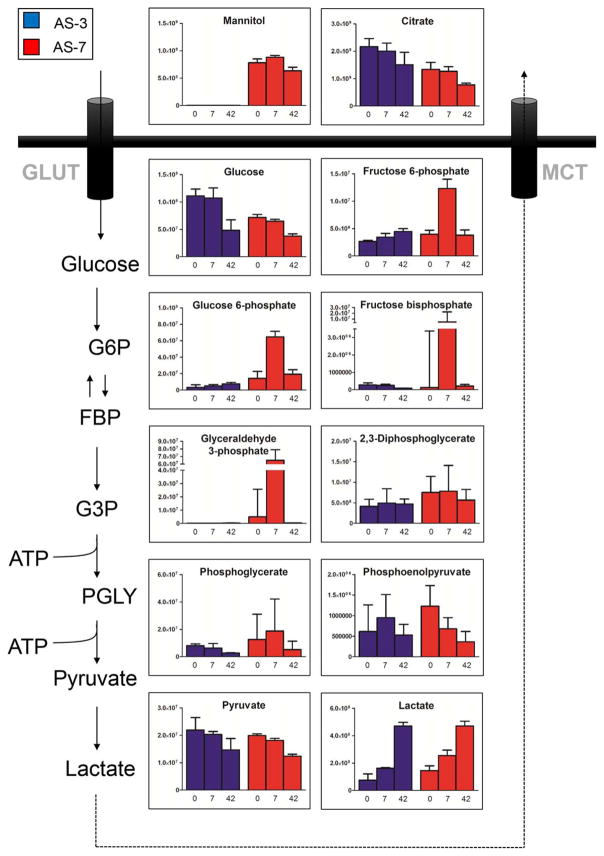

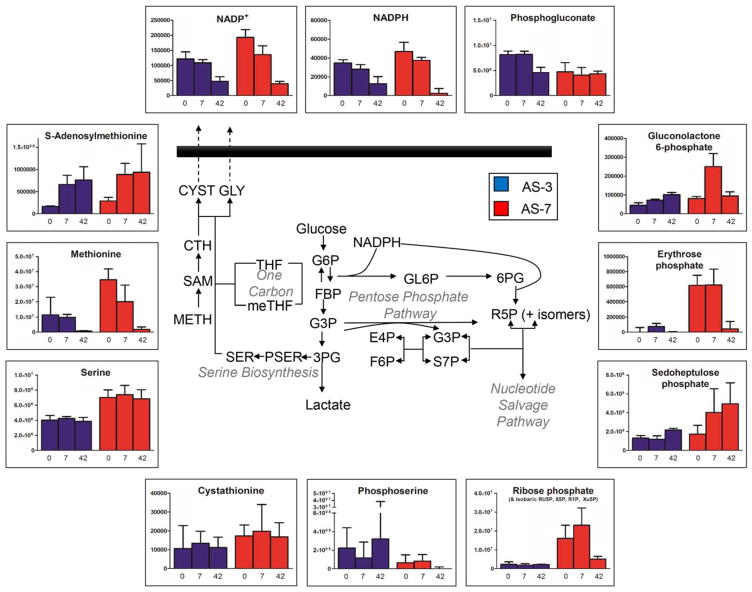

AS-7 RBCs showed consistently lower levels of glucose, as expected, yet had consistently higher levels of glycolytic intermediates (glucose 6-phosphate, fructose 6-phosphate, fructose bisphosphate, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, and diphosphoglycerate). However, although still overall higher, median levels of late triose phosphates or triose byproducts (pyruvate and lactate) were comparable to those in AS-3 counterparts (Fig. 3). Higher levels of hexose monophosphate shunt intermediates downstream to gluconolactone phosphate (Fig. 4) suggests that AS-7 fueled the PPP until Storage Day 7 better than AS-3. No significant difference was observed with respect to one-carbon metabolism, with serine levels being constitutively higher in AS-7 samples (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Glycolytic metabolism during storage in AS-3 (blue) and AS-7 (red). Median and interquartile ranges (error bars) are shown together with an overview of the metabolic pathway. GLUT =glucose transporters; MCT =monocarboxylate (lactate) transporters.

Fig. 4.

PPP and one-carbon metabolism during storage in AS-3 (blue) and AS-7 (red). Median and interquartile ranges (error bars) are provided, together with an overview of the metabolic pathway.

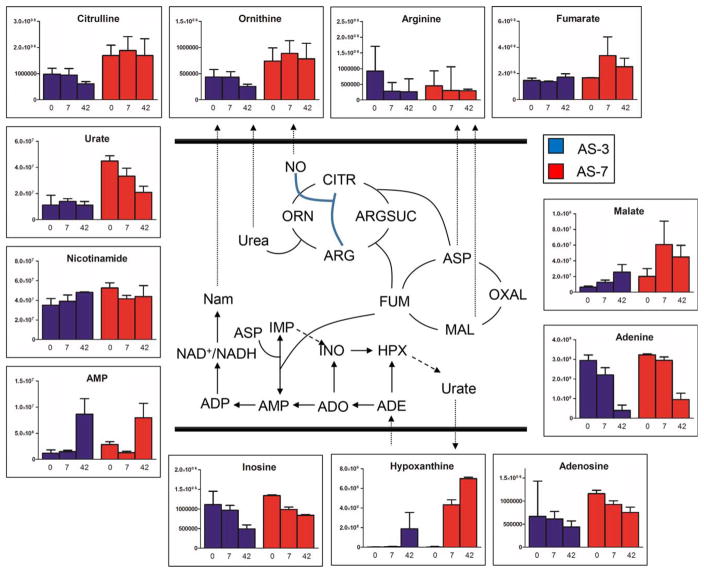

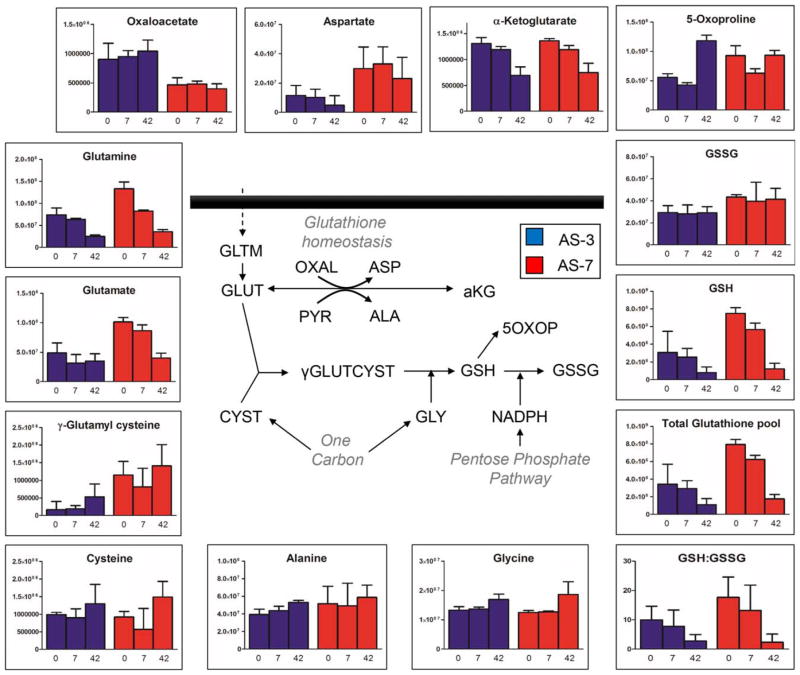

The total GSH pool (reduced, GSH; and disulfide, GSSG) was better preserved in AS-7 units suggesting improved GSH homeostasis throughout storage duration (Fig. 5). Comparable levels of 5-oxoproline (increase trend) were observed in both sets of samples, suggesting similar GSH turnover profiles. Higher levels of GSH precursor γ-glutamylcysteine and glutamate are indicative of faster GSH biosynthesis in AS-7 units (Fig. 5). However, comparable levels of glutamine and higher levels of trans-amination products alanine and aspartate, but not α-ketoglutarate, are suggestive of either higher glutamate anabolism (generation) or lower catabolism (utilization) in AS-7 units (Fig. 5). Transamination reactions might be coupled to cytosolic version of TCA cycle enzymes24,34 in AS-7 RBCs that result in the production of fumarate and malate (Fig. 6). Alternatively, fumarate production can be fueled by purine salvage reactions (Fig. 6). Increases of AMP and hypoxanthine were observed in RBC extracts in both sets of samples, especially in AS-7, at the expense of adenine and adenosine consumption (Fig. 6). Overall, purine levels were higher in AS-7, mirroring the differential composition. Arginine and its catabolites citrulline and ornithine were constitutively higher in AS-7 RBCs, while purine catabolite urate decreased in AS-7 units while it remained constant in AS-3 counterparts (Fig. 6). Storage-dependent, albeit AS-independent, free fatty acid accumulation was observed (including dodecanoic, tetra-decanoic, hexadecanoic, octadecanoic, tetradecenoic, hexadecenoic, octadecenoic acid, octadecanedioic, octadecatrienoic, icosatetraenoic, icosapentaenoic, and docosahexaenoic acid; Table S1).

Fig. 5.

Arginine and purine metabolism during storage in AS-3 (blue) and AS-7 (red). Median and interquartile ranges (error bars) are shown, together with an overview of the metabolic pathway.

Fig. 6.

GSH metabolism and amino acid and transamination homeostasis during storage in AS-3 (blue) and AS-7 (red). Median and interquartile ranges (error bars) are shown, together with an overview of the metabolic pathway.

DISCUSSION

AS-7 is a recently FDA-approved and CE-marked chloride-free alkaline RBC storage solution containing bicarbonate, adenine, glucose, mannitol, and phosphate designed to improve RBC metabolism during storage by increasing the range and capacity of pH buffering. It was previously known in the literature as EAS-81 (experimental AS-81).32 AS-7 theoretically enables an extended shelf life of up to 56 days.29 AS-7’s higher buffering range, from bicarbonate concentration, coupled with the absence of NaCl affects the initial intracellular pH through the so-called chloride shift mechanism. Briefly, excess of extracellular bicarbonate and absence of supernatant chloride levels promote the release of Cl− from RBCs to the AS medium. However, the Donnan effect ensues to maintain electrical neutrality by promoting hydroxyl anions diffusion into the cells in proportion to the chloride loss, which in turn results in intracellular alkalinization. The metabolic rationale behind this adjustment is that, by buffering intracellular pH, AS-7 increases the glycolytic fluxes as a result of the activation of the key regulatory enzyme of glycolysis phosphofructokinase.32 This phenomenon also relates to the increased buffer range of alkalinized Hb residues and the greater buffer capacity associated with greater carbon dioxide loss.29 Previous reports have documented improved storage quality of AS-7–stored RBCs in comparison to routine storage in AS-129 and SAGM.31 Briefly, storage in AS-7 resulted in lower hemolysis and higher in vivo survival, by protecting RBC integrity (reduced vesiculation rate, decreased glycophorin A–positive microparticles, and preserved morphology scores) and promoting glycolytic fluxes (faster glucose consumption, higher ATP and DPG levels, higher lactate production).29,31 Metabolic and biochemical superior performances of AS-7 in comparison to AS-1 enable overnight room temperature hold of whole blood before 42-day routine storage.30,31

While AS-7 performance has been compared to SAGM and AS-1, comparative studies against AS-3 are yet to be reported. Proteomics studies have suggested beneficial effects of storage in AS-3 in comparison to SAGM.35 Besides, AS-3 has a different composition in comparison to SAGM and AS-1, in that it is characterized by half the level of saline in comparison to SAGM and AS-1 (70 mmol/L vs. 150 and 154 mmol/L, respectively), high phosphate loading (23 mmol/L NaH2PO4, absent in other ASs), almost a double dose of adenine in comparison to SAGM (2 mmol/L vs 1.2 mmol/L), and half the dose of dextrose in comparison to AS-1 (55 mmol/L vs. 111 mmol/L).10 Similarly to chloride-free AS-7, AS-3 has been formulated to buffer intracellular pH by exploiting the chloride shift phenomenon through low chloride loading (410 mg of NaCl in AS-3 vs. 900 and 877 mg in AS-1 and AS-5, respectively10). High phosphate loading of AS-3 provides a key substrate for salvage reactions for ATP biosynthesis. While AS-7 formulation also includes 55 mmol/L mannitol, AS-3 is mannitol free.

Overall, statistical analyses of metabolomics data in this study suggest substantial equivalence of metabolic profiles of AS-3 and AS-7 RBCs, in terms of metabolic trends. However, key pathway-specific peculiarities were observed, mostly related to glycolysis and PPP, GSH homeostasis, and amino acid metabolism.

Consistent with clinical biochemistry data in the previous studies,29–31 storage in either AS resulted in impaired energy metabolism (ATP and DPG depletion), even though AS-7 better preserved DPG levels during early storage (Day 7). In the absence of additional time point measurements, current metabolic observations can be compared to previously reported intracellular pH measurements of AS-7 RBCs.29 In this view, we can but speculate a role for the buffering capacity of the two additives in modulating the activity of key enzymes such as biphosphoglycerate mutase (inhibited below pH 6.936) in a pH-dependent fashion. Indeed, while AS-7 is originally alkaline (pH 8.5), immediate RBC-dependent pH buffering is observed at 2 and 8 hours after cell processing (from 7.02 ± 0.04 to 6.96 ± 0.03),29 suggesting intracellular alkalinization. On the other hand, slower chloride shift promoted by low chloride AS-3, combined with lower initial pH (5.8 pH units)10 might result in similar buffering capacity only in the long term. Although energy metabolic profiles look consistent at the beginning and the end of the storage period, metabolic fluxes might be differentially balanced by the two ASs especially during early storage day, as hereby indicated by metabolomics analyses. Overall, AS-7 RBCs tended to be more glycolytic, as suggested by the higher lactate accumulation and faster total glucose depletion at the end of the storage period.

Higher activation of the PPP was observed in AS-7 units (especially on Storage Day 7; 12.5-fold increase; p <0.0005 ANOVA), suggesting a higher antioxidant potential of RBCs stored in this AS. However, progressive depletion of the whole NADP+ and NADPH pool was observed in both ASs, suggesting NADP breakdown in the long term (as supported by late nicotinamide accumulation on Storage Day 42). This is relevant with respect to storage-dependent PPP deregulation, in that NADP pools are key factors of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity,37 the rate-limiting enzyme of the PPP. As optimal pH for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity is 7.8, alkaline AS-7 might favor a quick activation of the PPP by quickly buffering intracellular pH.32

Serine synthesis is a branching pathway from glycolysis, fueled by late triose phosphates to generate serine and, ultimately, this pathway feeds into the synthesis of glycine and cysteine through one-carbon metabolism reactions.38,39 Despite the absence of mitochondria in RBCs, enzymes like serine hydroxymethyltransferase 1 (cytosolic isoform) have been previously reported in the RBC proteome.34 Of note, this metabolic pathway is intertwined with antioxidant responses in that it provides the building blocks for the biosynthesis of tripeptide GSH. While cysteine accumulation in the supernatant has been previously reported in AS-3 RBCs,21 cysteine efflux from in vivo circulating RBCs has been previously associated with senescence.2 Similar trends of glutamine consumptions in both ASs were observed, suggestive of similar de novo GSH biosynthesis trends. It should be noted that, since GSH biosynthesis is an ATP-dependent process,40 total GSH pools should be fueled by higher ATP availability. Unfortunately, direct measurements of ATP were not amenable to the present analysis (owing to the relative instability of the compound and technical issues related to sample shipping and in source fragmentation events during the MS analysis41). However, higher levels of the GSH precursor γ-glutamylcysteine and total levels of GSH and GSSG of in AS-7 RBCs are either suggestive of decreased turnover into 5-oxoproline12,26 (higher in AS-3 units by Storage Day 42) or recycling from oxidized (GSSG) to GSH as a function of NADPH availability resulting from PPP higher activation in AS-7 units. Additionally, it should be noted that the total GSH pool (reduced and oxidized) was higher in AS-7 units (2.1-fold; p < 0.0002 on Storage Day 7), further supporting a likely increased antioxidant potential of RBCs preserved in this AS. Altogether, these results are consistent with recent findings from Winterbourn’s group, indicating that storage in alkaline AS (not chloride free like AS-7) prevents oxidation of peroxiredoxin 2 better than incubation with glucose, rejuvenation, or supplementation of antioxidants, such as N-acetylcyteine.42 This is relevant in that metabolomics and morphological analyses had shown some potential beneficial effects of RBC storage in presence of antioxidants such as vitamin C9 and N-acetylcyteine.8

RBC storage in AS-3, SAGM, and AS-1 results in the alteration of nitrogen metabolism in the form of deregulated purine catabolism (ATP breakdown to AMP and adenosine) and deamination (to inosine and hypoxanthine), at the expenses of adenine consumption.20–23 Purine catabolism (conversion of deaminated IMP back to AMP at the expenses of aspartate) is interconnected to fumarate metabolism through salvage reactions, which in turn can be converted into malate and oxaloacetate by cytosolic fumarate hydratase and malate dehydrogenase, both enzymes in the RBC proteome.34 Of note, while storage-dependent accumulation of the intermediates of these pathways (purine catabolism and deamination, tricarboxylic acid, and urea cycle) had already been reported for AS-3 RBCs,25 here we show that this phenomenon is even more accentuated in AS-7 units. Such nitrogen metabolism patterns might influence nitric oxide metabolism in AS-7 units, as these metabolites provide substrate for the activity of arginase and/or endothelial nitric oxide synthase.43

Consistently with previous reports from AS-1,15 AS-3,25 and AS-526 RBCs, free fatty acids increased in older AS-7 units as well. This is relevant in that long-chain fatty acids represent key precursors of proinflammatory mediators that in turn trigger neutrophil priming and transfusion-related acute lung injury,44 a phenomenon that is in part abrogated by poststorage washing.45

Here we performed metabolomics analyses of AS-3 and AS-7 RBCs. We show similar metabolic trends in either AS. However, AS-7 units were characterized by sustained glycolytic and PPP fluxes and improved energy and redox homeostasis during early storage. While both ASs have been designed to exploit the chloride shift phenomenon to promote intracellular pH stability despite storage-dependent acidification of cytosol and media, the different mechanisms through which buffering is achieved (slow chloride efflux and Donnan effect in AS-3 and fast chloride efflux and Donnan effect plus direct bicarbonate buffering in AS-7) results in the same metabolic pathways being fueled at different rates. This effect promoted better preservation of DPG and redox poise (higher levels of PPP intermediates and stability and/or increased total GSH pools) in AS-7 in comparison to AS-3 RBCs especially during the first week of storage. Recent publications proposed preliminary correlations between AS-3 metabolic profiles and a key transfusion outcome, hemolysis.19 To further the relevance of metabolomics analyses in transfusion medicine, future studies should investigate whether significant correlations exist between metabolite levels and other markers of storage quality and transfusion outcomes, such as morphology, hemolysis, and 24-hour in vivo survival.1

Supplementary Material

Sheets 1 to 7 (vectorial - ∞ zoom in)

Fig. S1. Extract ion chromatogram for mannitol in AS-3 vs AS-7 samples.

Fig. S2. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis of metabolites levels in red blood cell extracts during storage in AS-3 or AS-7. Heat maps display intra-row normalized quantitative fluctuations for each metabolite (blue to red =low to high levels), as detected through UHPLC-MS metabolomics analyses of red blood cell extracts during storage in AS-3 or AS-7. Metabolite names are indicated on the right side of the figure, while storage time points are indicated on top of the map and are annotated through the color code explicated in the top left corner of the figure.

Acknowledgments

Funds and materials for this study were provided in part by Haemonetics, Inc.

The authors are grateful to the research subjects that made this study possible and Louise Herschel and Emily Herzog for strong technical support. The authors thank Haemonetics Corporation for their support.

ABBREVIATIONS

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- HCA

hierarchical clustering analysis

- PCA

principal component analysis

- PLS-DA

partial least square discriminant analysis

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- UPLC

ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

ZMS and LJD have received research support from Haemonetics. All remaining authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zimring JC. Established and theoretical factors to consider in assessing the red cell storage lesion. Blood. 2015;125:2185–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-567750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Alessandro A, Kriebardis AG, Rinalducci S, et al. An update on red blood cell storage lesions, as gleaned through biochemistry and omics technologies. Transfusion. 2015;55:205–19. doi: 10.1111/trf.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Alessandro A, D’Amici GM, Vaglio S, et al. Time-course investigation of SAGM-stored leukocyte-filtered red blood cell concentrates: from metabolism to proteomics. Haematologica. 2012;97:107–15. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.051789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fergusson DA, Hébert P, Hogan DL, et al. Effect of fresh red blood cell transfusions on clinical outcomes in premature, very low-birth-weight infants: the ARIPI randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:1443–51. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner ME, Ness PM, Assmann SF, et al. Effects of red-cell storage duration on patients undergoing cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1419–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lacroix J, Hébert PC, Fergusson DA, et al. Age of transfused blood in critically ill adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1410–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida T, Shevkoplyas SS. Anaerobic storage of red blood cells. Blood Transfus. 2010;8:220–36. doi: 10.2450/2010.0022-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pallotta V, Gevi F, D’Alessandro A, et al. Storing red blood cells with vitamin C and N-acetylcysteine prevents oxidative stress-related lesions: a metabolomics overview. Blood Transfus. 2014;12:376–87. doi: 10.2450/2014.0266-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stowell SR, Smith NH, Zimring JC, et al. Addition of ascorbic acid solution to stored murine red blood cells increases posttransfusion recovery and decreases microparticles and alloimmunization. Transfusion. 2013;53:2248–57. doi: 10.1111/trf.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparrow RL. Time to revisit red blood cell additive solutions and storage conditions: a role for “omics” analyses. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(Suppl 2):s7–11. doi: 10.2450/2012.003S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hess JR. An update on solutions for red cell storage. Vox Sang. 2006;91:13–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pertinhez TA, Casali E, Lindner L, et al. Biochemical assessment of red blood cells during storage by (1)H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Identification of a biomarker of their level of protection against oxidative stress. Blood Transfus. 2014;12:548–56. doi: 10.2450/2014.0305-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishino T, Yachie-Kinoshita A, Hirayama A, et al. In silico modeling and metabolome analysis of long-stored erythrocytes to improve blood storage methods. J Biotechnol. 2009;144:212–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishino T, Yachie-Kinoshita A, Hirayama A, et al. Dynamic simulation and metabolome analysis of long-term erythrocyte storage in adenine-guanosine solution. PloS One. 2013;8:e71060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roback JD, Josephson CD, Waller EK, et al. Metabolomics of ADSOL (AS-1) red blood cell storage. Transfus Med Rev. 2014;28:41–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Alessandro A, Gevi F, Zolla L. Red blood cell metabolism under prolonged anaerobic storage. Mol Biosyst. 2013;9:1196–209. doi: 10.1039/c3mb25575a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel RM, Roback JD, Uppal K, et al. Metabolomics profile comparisons of irradiated and nonirradiated stored donor red blood cells. Transfusion. 2015;55:544–52. doi: 10.1111/trf.12884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van ‘t Erve TJ, Wagner BA, Martin SM, et al. The heritability of metabolite concentrations in stored human red blood cells. Transfusion. 2014;54:2055–63. doi: 10.1111/trf.12605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van ‘t Erve TJ, Wagner BA, Martin SM, et al. The heritability of hemolysis in stored human red blood cells. Transfusion. 2015;55:1178–85. doi: 10.1111/trf.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimring JC, Smith N, Stowell SR, et al. Strain-specific red blood cell storage, metabolism, and eicosanoid generation in a mouse model. Transfusion. 2014;54:137–48. doi: 10.1111/trf.12264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clasquin MF, Melamud E, Rabinowitz JD. LC-MS data processing with MAVEN: a metabolomic analysis and visualization engine. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2012;Chapter 14(Unit14):11. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1411s37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paglia G, Palsson BØ, Sigurjonsson OE. Systems biology of stored blood cells: can it help to extend the expiration date? J Proteomics. 2012;76:163–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordbar A, Jamshidi N, Palsson BO. iAB-RBC-283: a proteomically derived knowledge-base of erythrocyte metabolism that can be used to simulate its physiological and pathophysiological states. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:110. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-5-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Alessandro A, Righetti PG, Zolla L. The red blood cell proteome and interactome: an update. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:144–63. doi: 10.1021/pr900831f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.D’Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Kelher M, et al. Routine storage of red blood cell (RBC) units in additive solution-3: a comprehensive investigation of the RBC metabolome. Transfusion. 2015;55:1155–68. doi: 10.1111/trf.12975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Alessandro A, Hansen KC, Silliman CC, et al. Metabolomics of AS-5 RBC supernatants following routine storage. Vox Sang. 2015;108:131–40. doi: 10.1111/vox.12193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gevi F, D’Alessandro A, Rinalducci S, et al. Alterations of red blood cell metabolome during cold liquid storage of erythrocyte concentrates in CPD-SAGM. J Proteomics. 2012;76(Spec No):168–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burger P, Korsten H, De Korte D, et al. An improved red blood cell additive solution maintains 2,3-diphosphoglycerate and adenosine triphosphate levels by an enhancing effect on phosphofructokinase activity during cold storage. Transfusion. 2010;50:2386–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cancelas JA, Dumont LJ, Maes LA, et al. Additive solution-7 reduces the red blood cell cold storage lesion. Transfusion. 2015;55:491–8. doi: 10.1111/trf.12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumont LJ, Cancelas JA, Maes LA, et al. Overnight, room temperature hold of whole blood followed by 42-day storage of red blood cells in additive solution-7. Transfusion. 2015;55:485–90. doi: 10.1111/trf.12868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veale MF, Healey G, Sran A, et al. AS-7 improved in vitro quality of red blood cells prepared from whole blood held overnight at room temperature. Transfusion. 2015;55:108–14. doi: 10.1111/trf.12779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hess JR, Rugg N, Joines AD, et al. Buffering and dilution in red blood cell storage. Transfusion. 2006;46:50–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2005.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nemkov T, D’Alessandro A, Hansen K. Three-minute method for amino acid analysis by UHPLC and high-resolution quadrupole orbitrap mass spectrometry. Amino Acids. 2015;47:2345–57. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2019-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goodman SR, Daescu O, Kakhniashvili DG, et al. The proteomics and interactomics of human erythrocytes. Exp Biol Med. 2013;238:509–18. doi: 10.1177/1535370213488474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D’Amici GM, Mirasole C, D’Alessandro A, et al. Red blood cell storage in SAGM and AS3: a comparison through the membrane two-dimensional electrophoresis proteome. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(Suppl 2):s46–54. doi: 10.2450/2012.008S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rapoport I, Berger H, Elsner R, et al. PH-dependent changes of 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate in human red cells during transitional and steady states in vitro. Eur J Biochem. 1977;73:421–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Torres-Ramírez N, Baiza-Gutman LA, García-Macedo R, et al. Nicotinamide, a glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase non-competitive mixed inhibitor, modifies redox balance and lipid accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells. Life Sci. 2013;93:975–85. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar P, Maurya PK. L-cysteine efflux in erythrocytes as a function of human age: correlation with reduced glutathione and total anti-oxidant potential. Rejuvenation Res. 2013;16:179–84. doi: 10.1089/rej.2012.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lutz HU, Bogdanova A. Mechanisms tagging senescent red blood cells for clearance in healthy humans. Front Physiol. 2013;4:387. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whillier S, Raftos JE, Sparrow RL, et al. The effects of long-term storage of human red blood cells on the glutathione synthesis rate and steady-state concentration. Transfusion. 2011;51:1450–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu YF, Lu W, Rabinowitz JD. Avoiding misannotation of in-source fragmentation products as cellular metabolites in liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Anal Chem. 2015;87:2273–81. doi: 10.1021/ac504118y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bayer SB, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Accumulation of oxidized peroxiredoxin 2 in red blood cells and its prevention. Transfusion. 2015;55:1909–18. doi: 10.1111/trf.13039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleinbongard P, Schulz R, Rassaf T, et al. Red blood cells express a functional endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Blood. 2006;107:2943–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baumgartner JM, Nydam TL, Clarke JH, et al. Red blood cell supernatant potentiates LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine response from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2009;29:333–8. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Biffl WL, Moore EE, Offner PJ, et al. Plasma from aged stored red blood cells delays neutrophil apoptosis and primes for cytotoxicity: abrogation by poststorage washing but not prestorage leukoreduction. J Trauma. 2001;50:426–31. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sheets 1 to 7 (vectorial - ∞ zoom in)

Fig. S1. Extract ion chromatogram for mannitol in AS-3 vs AS-7 samples.

Fig. S2. Hierarchical Clustering Analysis of metabolites levels in red blood cell extracts during storage in AS-3 or AS-7. Heat maps display intra-row normalized quantitative fluctuations for each metabolite (blue to red =low to high levels), as detected through UHPLC-MS metabolomics analyses of red blood cell extracts during storage in AS-3 or AS-7. Metabolite names are indicated on the right side of the figure, while storage time points are indicated on top of the map and are annotated through the color code explicated in the top left corner of the figure.