Abstract

The present paper reports on longitudinal associations between parenting stress and sexual satisfaction among 169 heterosexual couples in the first year after the birth of a first child. Actor Partner Interdependence Modeling (APIM) was used to model the effects of the mother’s and father’s parenting stress at 6 months after birth on sexual satisfaction at one year after birth. Based on social constructivist theory and scarcity theory, two hypotheses were posed: (a) mothers’ parenting stress will predict their own later sexual satisfaction whereas fathers’ parenting stress will not predict their own later sexual satisfaction (actor effects) and (b) mothers’ parenting stress will predict fathers’ later sexual satisfaction but fathers’ parenting stress will not predict mothers’ later sexual satisfaction (partner effects). On average, parents were only somewhat satisfied with their sex life. The first hypothesis was supported as greater parenting stress significantly predicted lower sexual satisfaction for mothers but not for fathers. The second hypothesis was also supported as mothers’ greater parenting stress significantly predicted less sexual satisfaction in fathers, whereas fathers’ parenting stress did not significantly predict mothers’ sexual satisfaction. We discuss how our results may be interpreted considering the social construction of gendered family roles.

Keywords: parental role, sexual satisfaction, marital relations, stress, relationship satisfaction, intimacy

Sexuality and sexual satisfaction have been shown to be important components of romantic relationships (Litzinger & Gordon, 2005; Shapiro & Gottman, 2005—in U.S. samples unless otherwise noted). Sexual frequency and satisfaction are generally associated with marital stability (Yeh, Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006), mental health (in an Australian sample, Davison, Bell, LaChina, Holden, & Davis, 2009), and the regulation of stress and maintenance of psychological well-being (in an Israeli sample, Ein-Dor & Hirschberger, 2012). Although sexual satisfaction is a unique contributor to happiness in romantic relationships (Impett, Muise, & Peragine, 2013), it often goes unmeasured in studies examining the transition to parenthood. This gap is significant given the stressful nature of the transition to parenthood for individuals and relationships (as documented in U.S. and Israeli samples: Doss, Cicila, Hsueh, Morrison, & Carhart, 2014; Lavee, Sharlin, & Katz, 1996; McBride, Schoppe, & Rane, 2002) and the influence of stress on sexual satisfaction (Bodenmann, Ledermann, & Bradbury, 2007 in a Swiss sample). Across the transition, the majority of couples experience some degree of decline in relationship quality (Mickelson & Joseph, 2012; Olsson, Lundqvist, Faxelid, & Nissen, 2005; Pauls, Occhino, Dryfhout, & Karram, 2008), and sexual activity may change in terms of frequency and meaning (Pacey, 2004). The current study aims to understand how mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress experienced at 6 months post-birth predicts their own and their partner’s sexual satisfaction at 12 months post-birth.

Our investigation is informed by social constructivist theory (Leeds-Hurwitz, 2009), which posits that gender roles are learned through interactions with others, and by scarcity theory (Bielby & Bielby, 1989), which posits that well-being declines as the number of roles and the amount of time spent on those roles increase. In the context of modern parenthood, women tend to be socialized to practice selfless parenting and devote large amounts of time and resources to a child-centered lifestyle (Büskens, 2001), whereas men tend to be held to less strict standards that better allow for making mistakes and for being involved in interests outside the home (Hays, 1998). Scarcity theory explains how differences in role socialization may create greater fatigue and stress for women than for men due to how women often bear the responsibility for the majority of the new roles during the transition to parenthood (Bielby & Bielby, 1989). Consequently, women may place more meaning on their identity as a parent than do men, which may increase women’s expectations to perform well. Scarcity theory explains that as women assume the greater burden of household work and child care, their well-being may decline. We argue that women may be socialized to adopt an ideal of motherhood that includes primary responsibility for meeting children’s needs and meeting unrealistic task demands and expectations, whereas men are often socialized to take a participatory role in parenting. Based on these perspectives, we believe that parenting stress holds deeper meaning for women and is therefore more salient for women’s sexual well-being.

The current study examines how parenting stress during the transition to parenthood predicts later sexual satisfaction in a sample of heterosexual couples in the United States. In doing so, we extend the existing knowledge concerning stress during the transition to parenthood and the potential effects of this stress in a number of ways. First, we examine actor and partner effects to explore the interdependence of the influence of parenting stress specifically felt by a mother and father on their own sexual satisfaction and their partner’s sexual satisfaction. Second, we use longitudinal data to examine the potential effect of parenting stress on sexual satisfaction over 6 months during the first year of parenthood. Third, we take a social constructivist (Leeds-Hurwitz, 2009) and scarcity theory approach (Bielby & Bielby, 1989) that highlights the importance of exploring socialized gender differences and illustrates how similar sources of stress can result in varied experiences for women and men during the transition to parenthood.

Sexual Satisfaction and Parenthood

Despite a preliminary understanding that sexual satisfaction is an important element of romantic relationships, the sexual lives of couples across the transition to parenthood need further study (Mickelson & Joseph, 2012; Olsson et al., 2005; Pauls et al., 2008). Sexual satisfaction is linked with a variety of predictors and outcomes in general, but its role during the transition to parenthood is less understood. In general, sexual satisfaction is associated with sexual frequency (Nicolosi, Moreira, Villa, & Glasser, 2004 in a Brazilian, Italian, Japanese and Malaysian sample) and emotionally satisfying relationships (Bodenmann et al., 2007; Carpenter, Nathanson, & Kim, 2009). However, at the transition to parenthood, sexual satisfaction tends to decline (Ahlborg, Dahlöf, & Hallberg, 2005 in a Swedish sample; Mickelson & Joseph, 2012). Sexual frequency also declines at the transition to parenthood and is not always replaced by other sexual or romantic behaviors (Ahlborg et al., 2005 in a Swedish sample). Despite the decline in sexual satisfaction and frequency, individuals appear to continue to enjoy sexual behavior across the transition to parenthood (Sherr, 1995).

Gender differences in response to stress may impact men’s and women’s experiences of sexual satisfaction. For example, Morokoff and Gilliland (1993) found that unemployed men reported relatively more instances of not being able to maintain an erection, but they found no increased sexual dysfunction among unemployed women. They argued that employment falls within the traditional masculine gender role and that the stress experienced from unemployment may impair feelings of masculine identity. However, longer employment hours impact women’s sexual satisfaction: Some researchers have found a curvilinear relation between work hours and sexual satisfaction among mothers 6 months after a first birth, such that the greatest sexual satisfaction was reported by mothers working part-time (Maas, McDaniel, Feinberg, & Jones, 2015). This finding was consistent with scarcity theory in that as work hours increased beyond a certain range, sexual satisfaction diminished. Scarcity theory helps explain how women, more so than men, feel a need to relinquish commitment to work in favor of family (Bielby & Bielby, 1989), and this may be especially true during the transition to parenthood. In summary, existing research indicates that particular kinds of stress may hold different meanings for men and women due to socialized gender roles.

Women also undergo physical changes during and after pregnancy that can negatively impact body image (Pauls et al., 2008), which has been linked to lower sexual satisfaction (Henderson, Harmon, & Newman, 2015; Pujols, Meston, & Seal, 2010). Women report difficulty combining the roles of mother and sexual partner (Montemurro & Siefken, 2012) because they may feel consumed by the stress of the mothering role and therefore experience less identification as a sexual person (Montemurro & Siefken, 2012).

Stress in the Transition to Parenthood

Increased stressors often arise around the transition to parenthood as couples balance a myriad of new tasks and learn how to coparent together. As couples move from being a couple to parents of an infant, the complexities of the coparenting relationship are introduced as parents learn to work together in rearing their child (Feinberg, 2003; McHale, Kuersten-Hogan, Lauretti, & Rasmussen, 2000). Over 50 years ago, LeMasters (1957) posited that part of the increased stress during the transition to parenthood derives from the disruption in the couple’s interaction as a pair as they move from a two- to three-member family. Each partner may feel displaced from enjoying the focused attention of the other as they take on the additional responsibilities of childcare (Cowan & Cowan, 1988; LeMasters, 1957). Women and men in less supportive circumstances may also experience heightened parenting stress (Raikes & Thompson, 2005), similar to that of low income parents (Reitman, Currier, & Stickle, 2002). Additionally, racial or ethnic minority parents (Nomaguchi & House, 2013) and gay and lesbian parents (Bos, Van Balen, Van Den Boom, & Sandfort, 2004: Tornello, Farr, & Patterson, 2011) may experience increased stress. Increases in stress due to parenthood generally have a negative impact on relationship satisfaction (see Cowan & Cowan, 2000 for a U.S. sample; Lavee, Sharlin, & Katz, 1996 for an Israeli sample), yet little is known about the relation between parenting stress and sexual satisfaction.

Gender roles in Western cultures socialize women to invest disproportionately large amounts of time in their child compared to men (Hays, 1998). Hays describes this cultural goal as “intensive mothering” (Hays, 1998, p. x). Modern, intensive mothering requires extensive emotional investment, expert skills, a large time investment, and creation of a child-centered home environment (Büskens, 2001). In a sample of Australian dual-earner couples, women often felt the brunt of the stress from parenting and household labor because they were shouldering the largest portion of responsibility (Dempsey, 2002). Women may also be expected to perform with immediate competence in this new parenting role, whereas men are less likely to feel this expectation (Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Riina, & Feinberg, 2012). Despite the increase in fathers’ involvement in the parenting role over the past decades (Dempsey, 2002), there is little societal pressure on fathers to perform early parenting duties with the same level of competence as women (LaRossa, 1998). Consequently, mothers may feel a greater impact of parenting stress, even if those levels of stress are similar to those of fathers, because fathers’ parenting role is often less demanding and sometimes elective (Wall & Arnold, 2007).

The increased salience of new mothers’ parental stress can be understood within the framework of the scarcity hypothesis, which holds that increasing the number of roles in which a person engages demands additional time and energy resulting in role overload and fatigue (Bielby & Bielby, 1989; Katz-Wise, Priess, & Hyde, 2010). Even mothers who do not subscribe to the idea of intensive mothering may feel social pressure to take on a number of roles inside and outside the home and thus may experience increased stress (Henderson, Harmon, & Newman, 2015). The combination of both higher levels of stress and a greater salience of stress for new mothers compared to fathers may have implications for sexual satisfaction across the transition to parenthood.

The Couple’s Relationship and Parenthood

Given that dominant socialized messages frequently encourage women to be self-sacrificing as they transition to motherhood (Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Hays, 1998), sexual satisfaction may become less of a priority. The demands on women for intensive mothering, pregnancy-linked physical changes, and diminished feelings of sexuality may impact mothers’ interest in sex and sexual satisfaction (Henderson et al., 2015; Montemurro & Siefken, 2012; Pujols, Meston, & Seal, 2010). As women experience more stress during the transition to parenthood, they may be less attuned to their partner’s needs (Cowan & Cowan, 1988; LeMasters, 1957). Although we have little research from which to draw for how parenting stress of one partner may influence the sexual satisfaction of the other partner, research indicates that one partner’s stress from work can influence the other partner’s well-being (Larson & Almeida, 1999; Schermerhorn, Chow, & Cummings, 2010; Thompson & Bolger, 1999). Additionally, research explains that as one partner feels greater stress or anxiety, their ability to positively communicate, emotionally connect, give attention to a partner, feel empathy, and refrain from judgment diminishes (Carson, Carson, Gil, & Baucom, 2004; Khaddouma, Gordon, & Bolden, 2015).

As mentioned above, some women may temporarily feel less sexual during the adjustment to parenting (Montemurro & Siefken, 2012), and this change may impact their husband or partner. Studies have shown that women spend less quality time with husbands after the birth of their first child (Dew & Wilcox, 2011) and that women’s preoccupation with mothering may create a feeling of sexual disconnection and rejection in their partner. Thus, as a mother’s stress increases during the transition to parenting, she may be less attentive to the relationship, less emotionally connected, and less empathic, which may influence not only her satisfaction but her partners’ satisfaction as well. Given that men are likely socialized to take the sexually assertive role (Siann, 2013), men may be highly sensitive to a sense of rejection given their partner’s diminished feelings of sexuality, sexual interest, and responsiveness. Thus, due to gender socialization and the often intensive roles women assume, parenting stresses may be more salient for women than for men, but these maternal parenting stresses likely have consequences for men because women feel less sexual, become less focused on their male partner, and instead become more focused on parenting the child.

The Current Study

To summarize, due to entrenched socialized gender roles, women may feel greater pressure than do men to invest large amounts of time in their child and carry the larger portion of responsibility in household work (Dempsey, 2002; Hays, 1998). The expectations of immediate competency and unrealistically high parenting skills for women, but not men, may also change the meaning and increase the impact of parenting stress for women (Cowan & Cowan, 2000, Hays, 1998; Matud, 2004). Moreover, under similar levels of parenting stress, women may feel a greater impact of parenting stress due to the socialized meanings surrounding the mothering experience, whereas fathers are often not socialized to approach fathering in an intensive way or to feel that fathering is intimately connected to their gender role or identity (Hays, 1998). Consequently, women likely perceive and feel differently about the parenting stress they experience due to socialized expectations for performance, and these feelings of pressure and stress may impact their sexual lives (Bodenmann et al., 2007). Thus, the first aim of the current study is to examine how parenting stress predicts sexual satisfaction during the transition to parenthood. We hypothesize that mothers’ parenting stress will predict their own later sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1a) whereas fathers’ parenting stress will not predict their own later sexual satisfaction (actor effects) (Prediction 1b).

The second aim of our study examines how each partner’s sexual satisfaction is influenced by their partner’s parenting stress. Studies have shown that stress experienced by one partner can easily spill over into the functioning of the other partner (Larson & Almeida, 1999; Schermerhorn et al., 2010; Thompson & Bolger, 1999). Additionally, as previously explained, parenting stress across the transition to parenthood may be more salient for women and increases in parenting stress for women may be indicators to her partner that she is consumed by motherhood and not as sexual as she used to be. Therefore, mothers’ parenting stress will predict fathers’ later sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2a) but fathers’ parenting stress will not predict mothers’ later sexual satisfaction (partner effects) (Prediction 2b). To examine both of our predictions, we utilize structural equation modeling and simultaneously include both women’s and men’s parenting stress at 6-months post-birth as predictors of women’s and men’s sexual satisfaction at 12-months post-birth.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants (169 heterosexual couples) in the present study were from a longitudinal study designed to test “Family Foundations,” a coparenting intervention program for couples expecting their first child (Feinberg & Kan, 2008). This program consists of eight classes, involving four delivered before birth and four after birth, which focus on strategies and skills that support “positive joint parenting” (Feinberg & Kan, 2008, p. 256). To be eligible for the study, first-time parents must have been at least 18 years of age, living together, and expecting their first child. Couples were mostly (n = 137, 81%) recruited from childbirth education programs at two hospitals located in the Northeast United States. All other couples were recruited from doctors’ offices (n = 13, 8%), newspapers ads or flyers (n = 12, 7%), by word of mouth (n = 5, 3%), or by unknown means (n = 2, 1%). These couples represent a non-clinical, low-risk sample (i.e., a sample of couples who were not identified for any particular marital problems or for being part of a clinical sample).

For the intervention, pretest data were collected via home interviews when mothers were pregnant (average weeks of gestation = 22.9, SD = 5.3, range = 9.43 to 36.00). Following the pretest, couples were randomly assigned to an intervention (n = 89) or to a no-treatment control condition (n = 80). Couples were also assessed at 6 months post-birth and 12 months post-birth via home interviews and paper-and-pencil questionnaires. Data on parenting stress were collected when the couple’s infant was approximately 6 months-old. Sexual satisfaction data were collected when the couple’s infant was approximately 12 months-old, although sexual satisfaction questions were not asked at 6 months. Our interest was in parenting stress during the infant’s first year, and although research has indicated there is an adjustment period after birth (Goldberg, Michaels, & Lamb, 1985), 6 months is a long enough period after the birth to gain a better assessment of the general level of parenting stress. However, sexuality is still variable at 6 months after birth for couples due to physical and hormonal changes among postpartum women (Pacey, 2004); by 12 months after birth, most couples have resumed sexual relations and found a new equilibrium.

Only those mothers and fathers who had at least some data on parenting stress or sexual satisfaction were included in our analyses (ns = 161 mothers, 156 fathers). In our analytic sample, mothers and fathers were primarily non-Hispanic White (n = 149, 92.5% and n = 141, 90.4% respectively), married (n = 135, 83.9% and n = 133, 85.3%), and in their late 20’s on average, with an average household income of $68,147 (SD = $31,811)—although income ranged greatly from $2,500 to $162,500. Additional details on men and women in the sample can be found in Table 1. We tested for gender differences in the demographic characteristics (i.e., MANOVA, follow-up ANOVAs, and chi-square tests). Significant gender differences emerged, F (4, 292) = 16.14, p < .001, and follow-up univariate tests showed that women were significantly younger, F (1, 295) = 6.76, p = .01, ηp2 = .02, had more years of schooling, F (1, 295) = 4.35, p = .04, ηp2 = .01, and were less likely to work outside the home, F (1, 295) = 43.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .13, than were the men in our sample.

Table 1.

Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Dads | Moms |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (SD) | 29.97 (5.48) a | 28.49 (4.91) b |

| Age Range (in years) | 20.11–54.73 | 18.26–41.46 |

| Married | 133 (85.3%) | 135 (83.9%) |

| Currently working | 148 (99.3%) a | 116 (74.8%) b |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 141 (90.4%) | 149 (92.5%) |

| Non-Hispanic African American or Black | 8 (5.1%) | 7 (4.3%) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 (1.3%) | 4 (2.5%) |

| American Indian, Eskimo, or Aleut | 1 (0.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.6%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Mixed Race/Ethnicity | 3 (1.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Education Level (highest year completed) | ||

| Mean Years in School (SD) | 14.68 (2.16) a | 15.14 (1.79) b |

| Grades of School | ||

| 9–11 years | 10 (6.5%) | 3 (1.9%) |

| 12 years | 30 (19.5%) | 18 (11.3%) |

| College/Years of School | ||

| 13–15 years | 29 (18.7%) | 35 (22.1%) |

| 16 years | 50 (32.5%) | 67 (42.1%) |

| 17 years or more | 35 (22.7%) | 36 (22.6%) |

Note. Means with SDs in parentheses are included where indicated. Otherwise, we provide the number for each category with percent of the sample. There are small amounts of missing data on some of the demographic characteristics; therefore, percentages include participants with data on each characteristic. Significant gender differences were found using a MANOVA within variables with different subscripts. F-tests are reported in text. Differing subscripts represent significant differences between mothers and fathers.

We also compared our analytic sample with participants who had missing data on the study measures or who dropped out of the study by 12 months on demographic variables utilizing a series of Chi-square and t-tests. There were no significant differences on ethnicity/race or intervention group status. However, mothers t (167) = −1.96, p = .05, d = .71 [but not fathers t (167) = −1.63, p = .10, d = .47] in our analytic sample were significantly older than their counterparts without usable data. Mothers and fathers in our analytic sample reported more years of education, t (165) = −2.73, p = .01, d = .98, and t (165) = −3.48,, p = .001, d = 1.01, respectively; had a higher family income, t (166) = −1.99, p = .048, d = .72, and t (166) = −2.13, p = .04, d = .61, respectively; and were more likely to be married, χ2 (1) = 5.98, p = .01, d = .38, and χ2 (1) = 12.57, p < .001, d = .57, respectively.

Measures

Sexual satisfaction

To measure satisfaction with one’s overall sex life at 12 months post-birth, mothers and fathers each responded on a 9-point scale to the item, “Regarding your sex life with your partner, would you say that you are overall” not at all satisfied (1) to very satisfied (9). Participants were asked to think about their experiences during the past 6 months. Higher scores indicate greater sexual satisfaction. Prior research has shown that this single-item measure is significantly related to new parents’ ratings of their sexual and romantic relationship, including satisfaction with the frequency of sex, romance, passion, and cuddling (Maas et al., 2015).

Parenting stress

Parenting stress was measured at 6 months post-birth and assessed with 27 items from the third edition of the Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (Abidin, 1995). Six items from the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscale and three items from the Difficult Child subscale were not utilized because Abidin (1995) found that they had lower factor loadings than the rest of the items. Items measured parental distress (e.g., “I find myself giving up more of my life to meet my children’s needs than I ever expected.”), parent–child dysfunctional interaction (e.g., “My child smiles at me much less than I expected.”), and parents’ reports of a difficult child (e.g., “My child turned out a to be a lot more of a problem than I had expected.”) using a 5-point rating scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Responses were averaged and this mean scale score was used in the analyses, with higher scores indicating greater parenting stress. Cronbach’s alphas (α) were .89 for mothers and .85 for fathers.

Results

In Table 2, we present results for our bivariate correlations and descriptives for mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress and sexual satisfaction. In our sample, despite adequate variability (range = 1.00–3.11 on a 5-point scale), mothers and fathers on average did not report being highly stressed by being a parent. On average, parents were only somewhat satisfied with their sex life. However, sexual satisfaction scores ranged across the entire 9-point scale, with about 69% (n = 101) of mothers and 55% (n = 77) of fathers falling into the somewhat to very satisfied range (i.e., a rating of 6 or above on the 9-point scale). Additionally, within families, mothers’ and fathers’ reports of parenting stress at 6 months did not significantly differ, t (148) = 0.06, p = .95, d = .01; however, mothers reported greater sexual satisfaction at 12 months than did fathers, t (136) = 2.95, p = .004, d = .50. At the bivariate level and not accounting for the dyadic nature of the data, mothers’ parenting stress at 6 months was negatively correlated with both mothers’ and fathers’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months; fathers’ parenting stress at 6 months negatively correlated only with mothers’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations for Parenting Stress and Sexual Satisfaction

| 6-Month Predictors

|

12-Month Outcomes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mom’s Parenting Stress | Dad’s Parenting Stress | Mom’s Sexual Satisfaction | Dad’s Sexual Satisfaction | |

| 6-Month Predictors | ||||

| Mom’s Parenting Stress | – | .29*** (n = 149) |

−.30*** (n = 140) |

−.35*** (n = 135) |

| Dad’s Parenting Stress | – | −.21* (n = 137) |

−.10 (n = 134) |

|

| 12-Month Outcomes | ||||

| Mom’s Sexual Satisfaction | – | .52*** (n = 137) |

||

| Dad’s Sexual Satisfaction | – | |||

| Mean | 1.92 | 1.91 | 6.25a | 5.70a |

| Standard Deviation | (0.43) | (0.45) | (2.06) | (2.10) |

| Actual Range | 1.04–3.11 | 1.00–3.07 | 1.00–9.00 | 1.00–9.00 |

| n | 152 | 149 | 149 | 141 |

Note. This sample comes from our overall analytic sample of 161 mothers and 156 fathers who had at least some parenting stress or some sexual satisfaction data. We assessed parenting stress on a 1–7 point scale. Sexual satisfaction was on a 1–9 point scale.

Significant difference between mother and father sexual satisfaction at 12 months, t (136) = 2.95, p < .01.

p < .05.

p < .001.

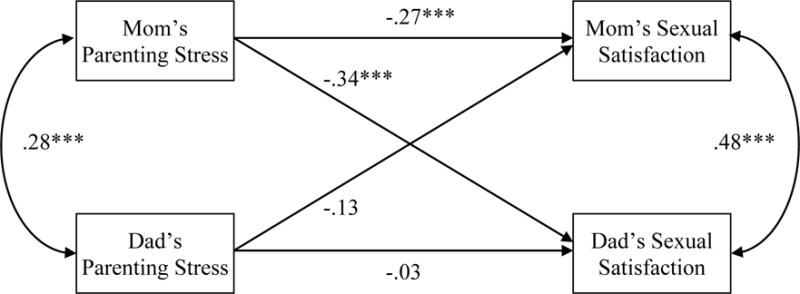

Actor Partner Interdependence Modeling (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006) was used to test our predictions concerning the individual and partner effects of parenting stress at 6 months post-birth on mothers’ and fathers’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months post-birth. This modeling included both mothers’ and fathers’ ratings of parenting stress as predictors of both mothers’ and fathers’ sexual satisfaction. We also correlated mothers’ and fathers’ variables as suggested by Kenny et al. (2006), which resulted in a saturated model, χ2 (2) = 0.52, p = .77; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = 0.00 (see Figure 1). We chose this methodological approach because mothers and fathers within couples are inherently interdependent, and examining the experience of one parent is often critical for wholly understanding the experiences of the other parent and vice versa. This approach was also best suited to analyze our predictions concerning the influence of each partner’s parenting stress on sexual satisfaction because of its ability to test the effect of one’s own level of parenting stress while also controlling for the potential influence of one’s partner’s parenting stress. We analyzed this dyadic data using structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS (Arbuckle & Wothke, 1999) because this strategy is capable of modeling effects for fathers and mothers simultaneously. We included 161 mothers and 156 fathers who had at least some data on parenting stress or sexual satisfaction in our model. Any missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood estimation (Newman, 2003).

Figure 1.

Actor and partner effects of parenting stress at 6 months predicting parents’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months post-birth. Standardized estimates are displayed. Intervention status was controlled in the model (paths not pictured here).

***p < .001

In addition to parenting stress and sexual satisfaction, we examined several control variables. Because our data come from a large-scale family intervention, intervention status was entered as a control in our final model. Other controls that have been identified in prior work on sexual satisfaction (Maas et al., 2015) or that could potentially influence levels of parenting stress, sexual satisfaction, or both (including family income, marital status, parent age, breastfeeding, and work status) were considered. To be the most parsimonious, these controls were ultimately removed from our final model because they were often unrelated to our study variables, and the results of our model did not change when controls were entered.

Standardized path estimates of the APIM predicting mothers’ and fathers’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months post-birth by their parenting stress at 6 months post-birth are presented in Figure 1. In controlling for the potential influence of intervention group status on sexual satisfaction in our model, we found no significant effect for intervention status—suggesting that the current intervention program was not a serious confound on the current results. Specifically for actor effects and in support of our predictions, mothers’ greater parenting stress predicted their own lower sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 1a), whereas fathers’ parenting stress did not predict their own sexual satisfaction (Prediction 1b). With regard to partner effects, mothers’ greater parenting stress predicted fathers’ lower sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2a), whereas fathers’ parenting stress did not predict mothers’ sexual satisfaction (Prediction 2b).

Discussion

We found that parenting stress has important implications for both mothers’ and fathers’ sexual satisfaction and that gender plays an important role in determining the impact of parenting stress on later sexual satisfaction. We used social constructivist theory (Leeds-Hurwitz, 2009) and scarcity theory (Bielby & Bielby, 1989) to guide our examination of how parenting stress predicts parents’ later sexual satisfaction during the transition to parenthood. We believe our findings are related to evidence that parenting stress has divergent meanings for men and women (Dempsey, 2002; Hays, 1998; Henderson et al., 2015).

Our findings support previous studies that suggest stress has an important role in the sexual satisfaction of couples (Ahlborg, Dahlöf, & Hallberg, 2005; Bodenmann et al., 2007; Mickelson & Joseph, 2012). However, in the current study we found that it was women’s and not men’s parenting stress that was influential for both partners’ sexual satisfaction. Generally, women tend to be socialized differently than men are around parenting, with mothering being experienced as more intensive and self-sacrificing than is fathering (Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Hays, 1998; Hauser, 2015). This difference likely explains a number of factors that contribute to gender differences in partner effects of parenting stress on sexual satisfaction.

A woman’s body goes through substantial changes across pregnancy, birth, and postnatal periods that affect her perspective of her body as sexual (Henderson et al., 2015; Olsson et al., 2005), whereas men’s bodies remain relatively unchanged. Cultural messages that place emphasis on the sexual attractiveness of young women, thin women, and innocent women might make women feel less sexual as a mother (Montemurro & Siefken, 2012), yet men are not generally faced with the same pressure as a father. For instance, Montemurro and Siefken (2012) interviewed women after becoming mothers and found that women’s ideas about their sex appeal and sexual desire had negatively changed after becoming mothers. Women’s changed sexual feelings were also complicated by fatigue and responsibility, resulting in women taking a break from perceiving themselves as sexual (Montemurro & Siefken, 2012). Women’s feelings of being less sexual or needing to take a break may indicate one potential mediating mechanism between stress and sexual satisfaction. For these reasons, the meaning of being a mother in conjunction with feeling stressed due to parenting likely changes how a woman perceives herself as a sexual person, and that in turn could be one of the reasons her own and her partner’s sexual satisfaction is affected. Women’s feelings about their sexuality during the transition to parenthood may provide future researchers an explanation for the mechanism of how parenting stress impacts sexual satisfaction.

As we expected, fathers’ parenting stress did not predict their own or their partner’s sexual satisfaction. Men’s sexual activity has been shown not to be affected by stress in some circumstances (Bodenmann et al., 2007). However, in areas where traditional identity roles are concerned (such as employment), men show lower sexual performance and lower intimacy satisfaction when stressed (Morokoff & Gillilland, 1993). Our findings then are likely due in part to the fact that parenting is often not central to the masculine gender role or men’s feelings as a sexual being (Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Hays, 1998; Hauser, 2015).

The current research corroborates previous research showing how a couples’ sexual relationship is interdependent (Leavitt & Willoughby, 2014; Theiss, 2011). This work extends the findings of interdependence to couples during the transition to parenthood. The current research demonstrates that even with similar levels of parenting stress on average, women’s stress (not men’s stress) is predictive of later sexual satisfaction. Thus, despite the same average levels of parenting stress felt by men and women, the meaning of the stress is different for women and men. Our research indicates that sexual satisfaction for both men and women during the transition period is partially steered by women’s stress, which is likely embedded in differential expectations for the mothering and fathering roles. As we noted, this is a complex process, and we do not wish to place responsibility on women as the sole driving force of sexual satisfaction across the transition to parenthood. These complex processes unfold over time, and we examine only a brief period of this process. We argue that women need more support and fewer (or perhaps more realistic) expectations placed on them during the transition to parenthood.

Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

There are some limitations in the current investigation that should be noted. These data come from a relatively satisfied, U.S., largely Caucasian, fairly educated, middle income, heterosexual, and coupled population. Therefore, future research needs to examine diverse populations, such as different cultures, ethnicities, age groups, LGBT couples, and couples in other socioeconomic categories. Our measure of sexual satisfaction, although serving our purposes of providing a global assessment of sexual satisfaction, could be improved upon in future studies. This one-item measure has shown good correlations with satisfaction in other areas such as the frequency of sex, romance, passion, and cuddling (Maas et al., 2015). However, future research could explore more specific areas of sexual satisfaction such as the frequency of kissing, cuddling, vaginal sex, oral sex, anal sex, length of foreplay, and orgasm quality. Future research could also measure sexual satisfaction beginning before pregnancy. Pregnancy is a physically demanding period for women and may change the dynamics of the sexual experience and levels of satisfaction (Elliott & Watson, 1985). Pre-pregnancy levels of sexual satisfaction would allow comparisons before and after both pregnancy and birth. Additionally, because sexual satisfaction was not assessed at 6 months, we could not control for prior levels of sexual satisfaction; currently we do not know whether parenting stress would be predictive over and above prior levels of sexual satisfaction.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths. Longitudinal data allow for a clearer understanding of the influence of stress at 6 months post-birth on both partners’ sexual satisfaction at 12 months after the birth of the child. Having data from both partners within couples across the transition to parenthood was also a strength because this breadth allowed us to find nuanced gender differences in the influence of stress centered around the transition to parenthood on women’s and men’s later sexual satisfaction. Our research also increases our understanding of the interdependence of a couple’s sexual satisfaction and how the experiences of one partner often spill over into those of the other.

Practice Implications

The finding that women’s parenting stress was more influential for couples’ sexual satisfaction dynamics has important implications. Both men and women can benefit from understanding the unrealistic and stress-inducing messages women receive and internalize. Men may thereby help to eliminate unhealthy messages in their relationship that can infuse parenting expectations, marital roles, and sexual expectations. Therapists and intervention scientists may address how women process the meaning of stress and their roles in the transition to parenthood, as well as how the coparenting relationship can support both men and women. Mothers’ might benefit from understanding their new roles with more realistic expectations of the transition to parenthood and from discussing with fathers how coparenting cooperation could provide greater support for women. Indeed, mothers’ perceptions of greater coparenting support have been linked reciprocally with improved relationship quality across the early years of parenthood (Le, McDaniel, Leavitt, & Feinberg, 2016). Guidance from research with how LGBT couples manage gender norms may be a useful guide for cisgender or heterosexual couples trying to redefine coparenting roles (Downing, 2013; Goldberg, 2010), without defaulting to heteronormative roles that may at times be harmful.

Conclusion

Our research highlights the importance of exploring socialized gender differences and can help couples address how similar sources of stress can result in very different experiences for women and men during the transition to parenthood. Although as a field we are far from understanding the complexities of sexual satisfaction for couples during the transition to parenthood, our research contributes to our understanding of how partners’ parenting stress influences sexual satisfaction. Specifically, our research shows how the mother’s stress can influence both her own sexual satisfaction and the father’s sexual satisfaction. The different meanings men and women place on stress during the transition to parenthood may impact the satisfaction felt in their sexual interactions and for women, in particular, may impact how they view their own sexuality. Sexual satisfaction has been associated with relationship stability (Yeh et al., 2006) and therefore is an important element in creating a more stable environment for both children and couples.

Acknowledgments

The present study was funded by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23 HD042575) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R21 MH064125-01), Mark E. Feinberg, principal investigator. Additionally, time on the preparation of our paper was partially supported for the second and third authors by Award Number T32 DA017629 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Chelom E. Leavitt, HDFS Department, The Pennsylvania State University

Brandon T. McDaniel, HDFS Department, The Pennsylvania State University

Megan K. Maas, HDFS Department, The Pennsylvania State University

Mark E. Feinberg, Prevention Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University

References

- Abidin RR. Manual for the parenting stress index. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlborg T, Dahlöf LG, Hallberg LRM. Quality of the intimate and sexual relationship in first-time parents six months after delivery. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42:167–174. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Wothke W. Amos 4.0 user’s guide. Chicago: Small Waters; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Biehle SN, Mickelson KD. First-time parents’ expectations about the division of childcare and play. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26:36. doi: 10.1037/a0026608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielby WT, Bielby DD. Family ties: Balancing commitments to work and family in dual earner households. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:776–789. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2117753. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G, Ledermann T, Bradbury TN. Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Personal Relationships. 2007;14:551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00171.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bos HM, Van Balen F, Van Den Boom DC, Sandfort TG. Minority stress, experience of parenthood and child adjustment in lesbian families. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2004;22:291–304. doi: 10.1080/02646830412331298350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Büskens P. The impossibility of “natural parenting” for modern mothers: On social structure and the formation of habit. Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering. 2001;3:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter LM, Nathanson CA, Kim YJ. Physical women, emotional men: Gender and sexual satisfaction in midlife. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:87–107. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson JW, Carson KM, Gil KM, Baucom DH. Mindfulness-based relationship enhancement. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:473–494. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80028-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. Who does what when partners become parents: Implications for men, women, and marriage. Marriage & Family Review. 1988;12:105–131. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CP, Cowan PA. When partners become parents: The big life change for couples. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Davison SL, Bell RJ, LaChina M, Holden SL, Davis SR. The relationship between self-reported sexual satisfaction and general well-being in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6:2690–2697. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey K. Who gets the best deal from marriage: Women or men? Journal of Sociology. 2002;38:91–110. doi: 10.1177/144078302128756525. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew J, Wilcox WB. If momma ain’t happy: Explaining declines in marital satisfaction among new mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00782.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Cicila LN, Hsueh AC, Morrison KR, Carhart K. A randomized controlled trial of brief coparenting and relationship interventions during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology. 2014;28:483–494. doi: 10.1037/a0037311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downing JB. Transgender-parent families. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, editors. LGBT-parent families. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 105–115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ein-Dor T, Hirschberger G. Sexual healing: Daily diary evidence that sex relieves stress for men and women in satisfying relationships. Journal of Social & Personal Relationships. 2012;29:126–139. doi: 10.1177/0265407511431185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SA, Watson JP. Sex during pregnancy and the first postnatal year. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1985;29:541–548. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3:95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Kan ML. Establishing family foundations: Intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:253–263. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg AE. Lesbian and gay parents and their children: Research on the family life cycle. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg WA, Michaels GY, Lamb ME. Husbands’ and wives’ adjustment to pregnancy and first parenthood. Journal of Family Issues. 1985;6:483–503. doi: 10.1177/019251385006004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser O. “I love being a mom so I don’t mind doing it all”: The cost of maternal identity. Sociological Focus. 2015;48:329–353. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2015.1059158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hays S. The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A, Harmon S, Newman H. The price mothers pay, even when they are not buying it: Mental health consequences of idealized motherhood. Sex Roles. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11199-015-0534-5. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Impett EA, Muise A, Peragine D. Sexuality in the context of relationships. In: Diamond L, Tolman D, editors. APA handbook of sexuality and psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 269–315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Wise SL, Priess HA, Hyde JS. Gender-role attitudes and behavior across the transition to parenthood. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:18–28. doi: 10.1037/a0017820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Khaddouma A, Gordon KC, Bolden J. Zen and the art of sex: Examining associations among mindfulness, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction in dating relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2015;30:268–285. doi: 10.1080/14681994.2014.992408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LaRossa R. Fatherhood and social change. Family Relations. 1988;37:451–457. doi: 10.2307/584119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Almeida DM. Emotional transmission in the daily lives of families: A new paradigm for studying family process. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:5–20. doi: 10.2307/353879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lavee Y, Sharlin S, Katz R. The effect of parenting stress on marital quality an integrated mother-father model. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:114–135. doi: 10.1177/019251396017001007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Le Y, McDaniel BT, Leavitt CE, Feinberg ME. Longitudinal associations between relationship quality and coparenting across the transition to parenthood: A dyadic perspective. 2016 doi: 10.1037/fam0000217. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt CE, Willoughby BJ. Associations between attempts at physical intimacy and relational outcomes among cohabiting and married couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2014;32:241–262. doi: 10.1177/0265407514529067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leeds-Hurwitz W. Social construction of reality. In: Littlejohn S, Foss K, editors. Encyclopedia of communication theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. pp. 891–894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeMasters EE. Parenthood as crisis. Marriage and Family Living. 1957;19:352–355. [Google Scholar]

- Litzinger S, Gordon KC. Exploring relationships among communication, sexual satisfaction, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2005;31:409–424. doi: 10.1080/00926230591006719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas M, McDaniel BT, Feinberg ME, Jones DE. Division of labor and multiple domains of sexual satisfaction among first-time parents. Journal of Family Issues. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0192513X15604343. Advanced online publication. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matud MP. Gender differences in stress and coping styles. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;37:1401–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2004.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McBride BA, Schoppe SJ, Rane TR. Child characteristics, parenting stress, and parental involvement: Fathers versus mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:998–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00998.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale JP, Kuersten-Hogan R, Lauretti A, Rasmussen JL. Parental reports of coparenting and observed coparenting behavior during the toddler period. Journal of Family Psychology. 2000;14:220–236. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.14.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson KD, Joseph JA. Postpartum body satisfaction and intimacy in first-time parents. Sex Roles. 2012;67:300–310. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0192-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montemurro B, Siefken JM. MILFs and matrons: Images and realities of mothers’ sexuality. Sexuality & Culture. 2012;16:366–388. doi: 10.1007/s12119-012-9129-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ, Gillilland R. Stress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30:43–53. doi: 10.1080/00224499309551677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman DA. Longitudinal modeling with randomly and systematically missing data: A simulation of ad hoc, maximum likelihood, and multiple imputation techniques. Organizational Research Methods. 2003;6:328–362. doi: 10.1177/1094428103254673. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Villa M, Glasser DB. A population study of the association between sexual function, sexual satisfaction and depressive symptoms in men. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;82:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi K, House AN. Racial-ethnic disparities in maternal parenting stress the role of structural disadvantages and parenting values. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2013;54:386–404. doi: 10.1177/0022146513498511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson A, Lundqvist M, Faxelid E, Nissen E. Women’s thoughts about sexual life after childbirth: Focus group discussions with women after childbirth. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2005;19:381–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacey S. Couples and the first baby: Responding to new parents’ sexual and relationship problems. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2004;19:223–246. doi: 10.1080/14681990410001715391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pauls RN, Occhino JA, Dryfhout V, Karram MM. Effects of pregnancy on pelvic floor dysfunction and body image: A prospective study. International Urogynecology Journal. 2008;19:1495–1501. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujols Y, Meston CM, Seal BN. The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010;7:905–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raikes HA, Thompson RA. Efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting stress among families in poverty. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2005;26:177–190. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman D, Currier RO, Stickle TR. A critical evaluation of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in a Head Start population. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:384–392. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, Feinberg ME. Involvement in childrearing and mothers’ and fathers’ adjustment. Family Relations. 2012;61:836–850. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00739.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schermerhorn AC, Chow SM, Cummings EM. Developmental family processes and interparental conflict: Patterns of microlevel influences. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:869–885. doi: 10.1037/a0019662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro AF, Gottman JM. Effects on marriage of a psycho-communicative-educational intervention with couples undergoing the transition to parenthood, evaluation at 1-year post intervention. The Journal of Family Communication. 2005;5:1–24. doi: 10.1207/s15327698jfc0501_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L. The psychology of pregnancy and childbirth. London: Blackwell Science Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Siann G. Gender, sex and sexuality: Contemporary psychological perspectives. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Theiss JA. Modeling dyadic effects in the associations between relational uncertainty, sexual communication, and sexual satisfaction for husbands and wives. Communication Research. 2011;38:565–584. doi: 10.1177/0093650211402186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A, Bolger N. Emotional transmission in couples under stress. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:38–48. doi: 10.2307/353881. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tornello SL, Farr RH, Patterson CJ. Predictors of parenting stress among gay adoptive fathers in the United States. Journal of Family Psychology. 2011;25:591–600. doi: 10.1037/a0024480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall G, Arnold S. How involved is involved fathering? An exploration of the contemporary culture of fatherhood. Gender & Society. 2007;21:508–527. doi: 10.1177/0891243207304973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh HC, Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality, and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:339–343. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]