Background

The 2016 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) evidence report on colorectal cancer screening concluded that no colorectal cancer screening methods reduce all-cause mortality. This conclusion was partially based on a meta-analysis of 4 randomized trials that compared flexible sigmoidoscopy screening with no screening. The meta-analysis aggregated results from the 2 age cohorts of 1 of the trials—the NORCCAP (Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention) study—as if these cohorts were a single trial (1). Aggregation of outcomes that have markedly different event rates, screening–control ratios, or both can create a Simpson paradox, a phenomenon where a finding exists in individual data groups that is absent or opposite when the groups are combined (2).

The NORCCAP study involved 2 distinct trial cohorts because of a postscreening decision to expand the inclusion age to younger persons. The cohorts were randomly assigned separately. The additional age cohort (50 to 54 years) had a lower event rate and was randomly assigned with a screen–control ratio of 1:5.4 rather than the ratio of 1:3 used in the original older cohort (55 to 64 years) (3). Therefore, the meta-analysis in the USPSTF evidence report may be confounded because the aggregated NORCCAP results were used.

Objective

To assess results of the NORCCAP study for a Simpson paradox and to repeat meta-analysis of all-cause mortality outcomes for screening flexible sigmoidoscopy using the 2 NORCCAP age cohorts as individual trials.

Methods

Data for all-cause mortality were extracted from the 4 studies specified in Table 1 of the USPSTF evidence report (1). Only published data and intention-to-treat outcomes were used. The 2 NORCCAP study age cohorts were included as individual trials using outcome data published in an author response to a comment (4). Meta-analysis was performed using R, Version 3.0.1 with the meta and metafor packages (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) (5). The fixed-effects model was chosen because of the lack of heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Sensitivity analysis repeated the meta-analysis with multiple random-effects models (Sidik–Jonkman, maximum likelihood, restricted maximum likelihood, Hedges–Olkin, empirical Bayes, and DerSimonian–Laird).

Results

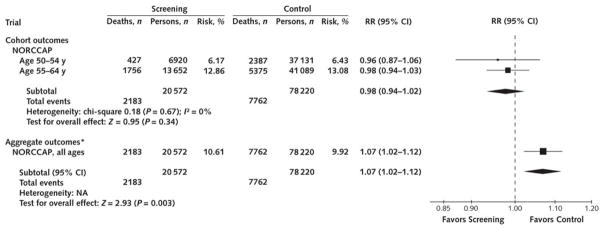

The relative risk (RR) for all-cause mortality favoring screening in the younger cohort of the NORCCAP study (ages 50 to 54 years) is 0.96 (95% CI, 0.87 to 1.06), whereas that for the older cohort (ages 55 to 64 years) is 0.98 (CI, 0.94 to 1.03). The RR for the combined summary estimate of these 2 cohorts shown in Figure 1 is 0.98 (CI, 0.94 to 1.02). When the 2 cohorts are aggregated into a single group rather than combined meta-analytically as 2 separate groups, the RR for all-cause mortality is 1.07 (CI, 1.02 to 1.12), favoring no screening (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RR for death in the NORCCAP individual cohorts versus the aggregate outcome.

NA = not applicable; NORCCAP = Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention; RR = relative risk.

* Showing Simpson paradox.

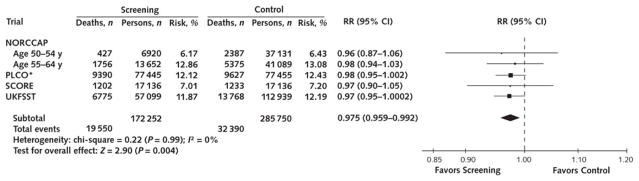

Meta-analysis of all of the flexible sigmoidoscopy trials using the individual NORCCAP study cohorts shows that flexible sigmoidoscopy reduces all-cause mortality (RR, 0.975 [CI, 0.959 to 0.992]; P = 0.004; I2 = 0%) at 11 to 12 years (Figure 2). On the basis of the assumed risk for death in the U.S. population of screening age (50 to 74 years), the absolute risk reduction is 3.0 deaths per 1000 persons invited to screening (CI, 1.0 to 4.9) after 11.5 years of follow-up. Sensitivity analysis showed no important change in outcome with use of different random-effects estimators or exclusion of any single trial.

Figure 2.

RR for death with screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy in randomized controlled trials.

NORCCAP = Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention; PLCO = Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian; RR = relative risk; SCORE = Screening for Colon Rectum; UKFSST = U.K. Flexible Sigmoidoscopy Screening Trial.

* This trial reports a modified all-cause mortality that excludes deaths from prostate, lung, and ovarian cancer because the intervention group was also screened for those types of cancer.

Discussion

Screening with flexible sigmoidoscopy reduces all-cause mortality with an absolute risk reduction that is clinically important relative to other preventive interventions. Aggregation of outcomes of the NORCCAP study in the USPSTF evidence report created a Simpson paradox that obscured the reduction in all-cause mortality by changing 2 statistically nonsignificant reductions into a statistically significant increase. This effect was large enough to nullify the reductions in all-cause mortality of the other trials in the meta-analysis.

A potential limitation of our meta-analysis of the trials is that the PLCO (Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian) cancer screening trial reports only modified all-cause mortality that excludes deaths from prostate, lung, and ovarian cancer because the intervention group was also screened for those types of cancer; however, exclusion of the PLCO trial does not change the result. Another limitation is that we did not examine whether outcomes might vary by age and sex.

More than 50 years after the announcement of the first clinical trial of cancer screening, a screening method has shown a reduction in the risk for death compared with no screening. If the primary goal of screening is to reduce the risk for death, then the evidence supporting flexible sigmoidoscopy is substantially stronger than that of other screening methods. We believe that colorectal cancer screening guidelines warrant reassessment to incorporate this evidence.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Olga Y. Gorlova, PhD (Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth University), and Gloria Ann Evans, FNP, DrPH (retired, Durham, North Carolina), for critical manuscript review and stylistic suggestions and Karen Matthias (Anchorage, Alaska) for stylistic suggestions.

Financial Support: Dr. Eberth is supported in part by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant from the American Cancer Society (MRSG-15-148-01-CPHPS). Ms. Josey is supported in part by grant T32-GM081740 from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, Rutter CM, Webber EM, O’Connor E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315:2576–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julious SA, Mullee MA. Confounding and Simpson’s paradox. BMJ. 1994;309:1480–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6967.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretthauer M, Gondal G, Larsen K, Carlsen E, Eide TJ, Grotmol T, et al. Design, organization and management of a controlled population screening study for detection of colorectal neoplasia: attendance rates in the NORCCAP study (Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:568–73. doi: 10.1080/00365520252903125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holme O, Loberg M, Kalager M. Colorectal cancer and the effect of flexible sigmoidoscopy screening—reply [Letter] JAMA. 2014;312:2411–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2010. [Google Scholar]