Abstract

Background

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a heterogeneous hereditary connective tissue disorder clinically hallmarked by increased susceptibility to bone fractures.

Methods

We analyzed a cohort of 77 diagnosed OI patients from 49 unrelated Palestinian families. Next‐generation sequencing technology was used to screen a panel of known OI genes.

Results

In 41 probands, we identified 28 different disease‐causing variants of 9 different known OI genes. Eleven of the variants are novel. Ten of the 28 variants are located in COL1A1, five in COL1A2, three in BMP1, three in FKBP10, two in TMEM38B, two in P3H1, and one each in CRTAP,SERPINF1, and SERPINH1. The absence of disease‐causing variants in the remaining eight probands suggests further genetic heterogeneity in OI. In general, most OI patients (90%) harbor mainly variants in type I collagen resulting in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. However, in our cohort almost 61% (25/41) were affected with autosomal recessive OI. Moreover, we document a 21‐kb genomic deletion in the TMEM38B gene identified in 29% (12/41) of the tested probands, making it the most frequent OI‐causing variant in the Palestinian population.

Conclusion

This is the first genetic screening of an OI cohort from the Palestinian population. Our data are important for genetic counseling of OI patients and families in highly consanguineous populations.

Keywords: Autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, next‐generation sequencing, osteogenesis imperfecta

Introduction

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) or brittle bone disease is a rare heterogeneous hereditary disorder with an incidence of 1:15,000 to 1:25,000 births (Stoll et al. 1989; Martin and Shapiro 2007). The clinical hallmark of OI is a low bone mass that causes bone fragility, easy fracturing, and growth impairment. Other features may include blue sclerae, dentinogenesis imperfecta, and hearing loss (van Dijk and Sillence 2014). The clinical heterogeneity of OI ranges from hardly detectable mild OI with few fractures to perinatal lethality. Autosomal dominant (AD), autosomal recessive (AR), and X‐linked inheritance patterns have been described previously. The current clinical classifications elaborating on the OI classification of 2010 reveal the importance of phenotyping for classifying and diagnosing OI (Warman et al. 2011; van Dijk and Sillence 2014; Bonafe et al. 2015). Forlino and Marini (2016) subdivide OI genes in five functional groups according to the pathway and mechanism in which they are involved. We present our results according to these functional groups. However, several reported OI genes cannot be classified, including TAPT1, SEC24D, P4HB, SPARC, and MBTPS2 (OMIM#300294) (Garbes et al. 2015; Mendoza‐Londono et al. 2015; Rauch et al. 2015; Symoens et al. 2015; Lindert et al. 2016).

Middle Eastern populations, especially Arabs, are highly consanguineous because of cultural reasons. Population‐based surveys show consanguinity rates of 20–50% in all marriages in Arab countries (Tadmouri et al. 2009). In Palestine, this rate has been estimated to be about 40% (Assaf and Khawaja 2009; Tadmouri et al. 2009; Sirdah 2014). Consequently, AR disorders are common in these populations. In contrast to the high frequency of the AD forms caused by defects in the structure or quantity of type I collagen in nonconsanguineous populations (Byers and Pyott 2012; Rohrbach and Giunta 2012), AR forms of OI are expected to be more common in highly consanguineous populations. The many AR genes identified in consanguineous families have revealed new pathogenic mechanisms. Some genes have been subjected to intensive study, such as CRTAP, P3H1, and PPIB, which encode components of the collagen prolyl 3‐hydroxylation complex (Marini and Blissett 2013; Homan et al. 2014; Forlino and Marini 2016) and BMP1, which encodes the C‐propeptidase of type I procollagen and causes AR OI through a procollagen processing defect. In addition, BMP1 activates lysl oxidase, which has a critical role in collagen cross‐linking (Panchenko et al. 1996; Borel et al. 2001). Other genes have not been fully explored: (i) SERPINF1, encoding the pigment epithelium‐derived factor protein (PEDF), which has a crucial role in bone homeostasis and osteoid mineralization (Minillo et al. 2014); (ii) SP7, encoding the transcription factor Sp7 protein; (iii) WNT1, encoding the proto‐oncogene Wnt‐1 protein; and (iv) CREB3L1, encoding the endoplasmic reticulum stress transducer “old astrocyte specifically induced substance” (OASIS) (Lapunzina et al. 2010; Keupp et al. 2013; Symoens et al. 2013). A recently identified AR OI gene is TMEM38B, encoding the TRIC‐B protein (Shaheen et al. 2012). It has been proposed that the TRIC‐B channel acts as a counter ion to facilitate the Ca2+ efflux from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) mediated by inositol 1,4,5‐trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) (Fink and Veigel 1996). Impaired bone mineralization and insufficient collagen matrix in bones have been reported in TRIC‐B knockout mice, which die immediately after birth from respiratory complications. Moreover, it was proposed in the same study that TRIC‐B knockout osteoblasts inhibit IP3R‐mediated Ca2+ release, leading to impaired Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ store overload (Zhao et al. 2016). A recent study based on data obtained from cells of OI patients reported higher ER stress accompanied by defective matrix collagen due to the decreased synthesis, secretion, and deposition of type I collagen, in addition to the impaired assembly and lysyl hydroxylation of procollagen fibers (Cabral et al. 2016). Here, we report for the first time an in‐depth molecular screening of a large cohort of Palestinian OI families and describe a wide range of mostly autosomal recessive variants, with phenotypes ranging from mild to severe.

Materials and Methods

Ethical compliance

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University Hospital (Belgium) and the ethics committee of Birzeit University (Palestine).

Patients

Forty‐nine Palestinian families with 77 affected family members participated in the study. Participating families were distributed all over Palestine, with 38 residing in the West Bank and 11 in Gaza. Thirty‐two (65%) of the 49 families were consanguineous. Blood samples were obtained from affected individuals after obtaining appropriate informed consent from the participant and/or the legal guardians.

Cell culture and isolation of DNA and RNA

Genomic DNA was isolated and purified from whole EDTA blood by Qiagen DNeasy Kit using standard protocols (Qiagen, Frankfurt, Germany). Skin biopsies were obtained from probands affected by a disease‐causing splice variant in FKBP10. RNA was isolated with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized using the M‐MLV cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen).

Analysis strategies

A total of 82 primer sets were developed to amplify the exons and their intron boundaries of OI panel 1, associated with AD OI, including COL1A1 (OMIM# 120150), COL1A2 (OMIM# 120160), and IFITM5 (OMIM# 614757); 185 primer sets were developed to amplify OI panel 2, associated with AR OI, including SERPINF1 (OMIM# 172860), SERPINH1 (OMIM# 600943), P3H1 (OMIM# 610339), FKBP10 (OMIM# 607063), TMEM38B (OMIM# 611236), CRTAP (OMIM# 605497), SP7 (OMIM# 606633), BMP1 (OMIM# 112264), CREB3L1 (OMIM# 616215), PLOD2 (OMIM# 601865), TAPT1 (OMIM# 612758), PPIB (OMIM# 123841), SEC24D (OMIM# 607186), P4HB (OMIM# 176790), and SPARC (OMIM# 182120). All primer sequences were obtained from Pxlence (Dendermonde, Belgium). The coding regions and flanking introns were amplified using a 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster city, CA, USA). Depending on the clinical presentation and family history, either OI panel 1 or OI panel 2 was analyzed. If the screening was negative, the other panel was investigated. Samples (50 ng DNA) were prepared using the Nextera sample preparation protocol (Nextera XT DNA Sample Prep Kit) (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and sequenced on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, Inc.). Alterations were confirmed by bidirectional Sanger sequencing using an ABI3730XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Nomenclature is based on the HGMD guidelines and refers to NCBI reference sequence NM_000088.3/NP_000079.2 for COL1A1, NM_000089.3/NP_000080.2 for COL1A2, NM_006129.4/NP_006120.1 for BMP1, NM_006371.4/NP_006362.1 for CRTAP, NM_022356.3/NP_071751.3 for P3H1, NM_018112.1/NP_060582.1 for TMEM38B, NM_001207014.1/NP_001193943.1 for SERPINH1, NM_021939.3/NP_068758.3 for FKBP10, and NM_002615.5/NP_002606.3 for SERPINF1. Pathogenic variants were evaluated with the Alamut software (Alamut Visual, Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) and the Mutalyzer software (https://mutalyzer.nl/batchNameChecker). The results were submitted to the OI variant database (https://oi.gene.le.ac.uk) (Dalgleish 1997, 1998).

To identify disease‐causing variants, all alterations were filtered against the OI variant database (https://oi.gene.le.ac.uk), the dbSNP database (Sherry et al. 2001), and the ExAc database (Lek et al. 2016) (MAF <1%). Variants were considered pathogenic if they satisfied previously published criteria (Symoens et al. 2012).

Linkage analysis

Microsatellite markers within the ±1 Mb flanking the gene being investigated were selected from the Genethon and Marshfield genetic map for linkage analysis. Markers and primer sequences are shown in Table S1. PCR reactions were performed (reaction conditions are available upon request). One μL PCR product was added to 10 μL of a mixture of GeneScan 500 LIZ Size Standards (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and formamide, and analyzed on an ABI3730XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). The results were analyzed using GeneMapper software V5.0 (Applied Biosystems, Inc.).

Results

Alterations causing defects in collagen synthesis, structure, or processing

We identified variants in COL1A1, COL1A2, or BMP1 in 19 of the 49 Palestinian OI probands (Table 1). Eleven of 19 probands harbored 10 different COL1A1 disease‐causing variants. Two probands had glycine substitutions in the α‐helical region c.3226G>A p.(Gly1076Ser) and c.3118G>A p.(Gly1040Ser), and a third proband carried an aspartate substitution in the C‐propeptide domain c.4237G>A p.(Asp1413Asn). The phenotype of these probands is in agreement with the reports that associate these three substitutions with severe OI (Marini et al. 2007; Bodian et al. 2009; Pyott et al. 2011; Barkova et al. 2015; Lindahl et al. 2015). Three probands had a splice site variant, including variants c.1200+1G>A and c.1299+1G>A, previously reported to cause an in‐frame skip of exons 18 and 19, respectively, and a novel splice site variant, c.3531+1G>T, predicted to cause an in‐frame skip of exon 47. Those three splice site variants were associated with mild to moderate phenotypic features characterized primarily by short stature and recurrent fractures, which is in agreement with previous descriptions (Willing et al. 1993; Benusiene and Kucinskas 2003). Finally, we found four premature termination variants associated with mild phenotypic features. The c.2426dup p.(Ala811Cysfs*10) and c.3749del p.(Gly1250Alafs*81) variants are novel, whereas the c.3567del p.(Gly1190Valfs*49) and c.189C>A p.(Cys63*) variants have been reported previously (Dalgleish 1997, 1998; Lindahl et al. 2015).

Table 1.

Clinical data overview

| Patient ID | Gene | c.DNA variant | Predicted protein | Consanguinity | Sex | Age | Number in pedigree | Recurring fractures | Blue sclera | Hearing loss | Short stature | S & D extremities | Pectus deformity | Kyphoscoliosis | Contractures | Hernia | Dentinogenesis imperfecta | Wheelchair |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AN_001998 | COL1A1 | c.3531+1G>Ta | – | M | 5 | 15 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| AN_001999 | COL1A1 | c.3226G>A | p.(Gly1076Ser) | – | M | 7 | >20 | + | – | + | + | – | + | – | + | – | + | |

| AN_002000 | COL1A1 | c.3567del | p.(Gly1190Valfs*49) | – | F | 3 | 4 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| AN_005801 | COL1A1 | c.2426dupa | p.(Ala811Cysfs*10) | – | F | 15 | 15 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| AN_005802 | COL1A1 | c.4237G>A | p.(Asp1413Asn) | – | M | 4 | >25 | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | |

| AN_005803 | COL1A1 | c.3118G>A | p.(Gly1040Ser) | – | F | 7 | >20 | + | – | + | NA | + | – | + | + | + | + | |

| AN_005804 | COL1A1 | c.1200+1G>A | – | F | 2 | 4 | + | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | NR | ||

| AN_005805 | COL1A1 | c.3749dela | p.(Gly1250Alafs*81) | – | M | 6 | II:1 | 14 | + | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| F | 4 | II:2 | 6 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005806 | COL1A1 | c.3567del | p.(Gly1190Valfs*49) | + | M | 10 | II:3 | 8 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| AN_005807 | COL1A1 | c.189C>A | p.(Cys63*) | – | M | 16 | 10 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | NA | – | |

| AN_005808 | COL1A1 | c.1299+1G>A | – | F | 10 | >40 | + | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | + | ||

| AN_005809 | COL1A2 | c.1072G>A | p.(Gly358Ser) | – | F | 1 | 5 | + | NA | + | + | – | – | + | – | NA | NR | |

| AN_005810 | COL1A2 | c.1031_1033del | p.(Val345del) | – | F | 30 | >80 | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | |

| AN_005811 | COL1A2 | c.3305G>A | p.(Gly1102Asp) | + | F | 4 | 10 | + | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| AN_005812 | COL1A2 | c.1991G>Ta | p.(Gly664Val) | – | M | 40 | II:2 | >30 | NA | – | + | + | – | + | – | – | + | + |

| F | 14 | III:2 | >20 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | |||||

| F | 12 | III:3 | >15 | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | – | + | + | |||||

| AN_005813 | COL1A2 | c.3034G>A | p.(Gly1012Ser) | – | F | 8 | 18 | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | – | + | ||

| AN_005814 | BMP1 | c.688C>Ga | p.(Arg230Gly) | + | M | 23 | >25 | – | – | + | – | + | + | – | – | – | + | |

| AN_005815 | BMP1 | c.691G>Ta | p.(Asp231Tyr) | + | M | 19 | IV:6 | >10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| M | 26 | IV:4 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005816 | BMP1 | c.818C>Ta | p.(Ala273Val) | + | F | 10 | >100 | + | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | + | |

| AN_005817 | CRTAP | c.976C>Ta | p.(Gln326*) | + | M | 9 | >40 | + | – | + | + | + | + | NA | + | – | + | |

| AN_005818 | CRTAP | c.976C>Ta | p.(Gln326*) | + | M | 7 | >30 | + | – | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + | |

| 0000968 | P3H1 | c.2041C>T | p.(Arg681*) | + | M | 8 | IV:1 | >40 | + | – | + | + | + | + | NA | + | + | + |

| AN_005819 | P3H1 | c.1080+1G>T | + | F | 33 | II:6 | >100 | – | + | + | + | + | NA | NA | – | – | + | |

| F | 22 | II:10 | >100 | – | – | + | + | + | + | NA | – | – | + | |||||

| AN_005820 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 14 | II:4 | >20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + |

| F | 12 | II:3 | >20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | |||||

| F | 15 | II:5 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005821 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 10 | V:9 | 6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| F | 19 | V:6 | 4 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| M | 20 | V:12 | 9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| M | 17 | V:2 | >10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005822 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | F | 1 | NA | – | – | – | + | – | – | – | – | – | NR | |

| AN_005823 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del\c.507G>A | p.(Gly152Alafs*5)\p.(Trp169*) | – | M | 6 | 15 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | |

| AN_005824 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 4 | 5 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| AN_005825 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 8 | 6 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | |

| AN_005826 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 27 | II:4 | >10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| AN_005827 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 7 | II:10 | 4 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

| F | 23 | II:6 | 7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005828 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | M | 39 | II:2 | >10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + |

| F | 28 | II:5 | >10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | |||||

| AN_005829 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | F | 4 | 3 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | |

| AN_005830 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | F | 3 | 6 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – | |

| AN_005831 | TMEM38B | c.455‐542del | p.(Gly152Alafs*5) | + | F | 7 | IV:3 | >20 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + |

| M | 13 | IV:6 | 15 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | + | |||||

| F | 10 | IV:7 | 5 | + | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |||||

| AN_005832 | SERPINH1 | c.314_325dela | p.(Glu105_His108del) | + | M | 2 | 4 | + | – | NA | NA | + | – | – | – | + | + | |

| AN_005833 | FKBP10 | c.391+4A>Ta | + | M | 41 | V:6 | >50 | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | |

| F | 43 | V:5 | >50 | + | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | + | + | |||||

| M | 32 | V:8 | >100 | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| F | 30 | V:9 | >100 | + | – | + | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| F | 15 | V:12 | 20 | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| M | 14 | V:13 | 15 | + | – | – | – | + | + | + | – | + | + | |||||

| M | 6 | V:14 | 6 | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| F | 9 | V:3 | >12 | + | – | – | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| AN_005834 | FKBP10 | c.391+4A>Ta | + | F | 7 | >30 | – | – | + | – | + | – | + | – | – | + | ||

| AN_005835 | FKBP10 | c.1330C>T | p.(Gln444*) | + | F | 16 | IV:5 | >30 | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | + | + |

| F | 11 | IV:7 | >20 | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| M | 14 | IV:11 | >30 | + | – | + | + | + | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| M | 10 | IV:12 | >20 | + | – | + | + | – | + | + | – | – | + | |||||

| AN_005836 | FKBP10 | c.1276dela | p.(Gln426Argfs*10) | + | M | 36 | V:2 | >15 | NA | – | + | + | + | – | + | – | – | + |

| AN_005837 | SERPINF1 | c.242C>G | p.(Ser81Cys) | + | M | 7 | >20 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | + | – |

Nomenclature refers to NCBI RefSeq NM_000088.3/NP_000079.2 for COL1A1, NM_000089.3/NP_000080.2 for COL1A2, NM_006129.4/NP_006120.1 for BMP1, NM_006371.4/NP_006362.1 for CRTAP, NM_022356.3/NP_071751.3 for P3H1, NM_018112.1/NP_060582.1 for TMEM38B, NM_001207014.1/NP_001193943.1 for SERPINH1, NM_021939.3/NP_068758.3 for FKBP10, and NM_002615.5/NP_002606.3 for SERPINF1. Patient ID corresponds to the identifiers found in the OI Variant Database (https://oi.gene.le.ac.uk/). S & D extremities, short and deformed extremities; NA, not available; NR, not relevant.

Novel mutation.

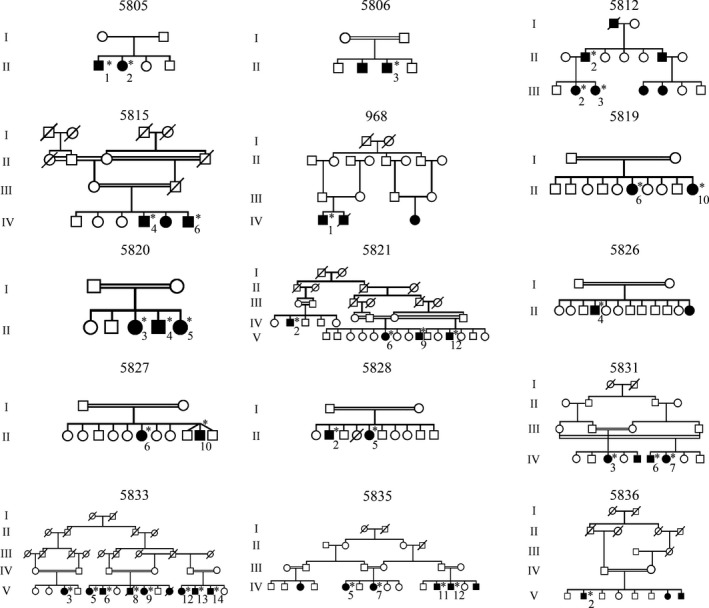

Five probands had a COL1A2 variant. Four were glycine substitutions located in the α‐helical region of the α2(I) chain. One of them, c.1991G>T p.(Gly664Val), was novel, and segregation was confirmed in two affected family members (Fig. 1, 5812). The fifth variant is an in‐frame deletion c.1031_1033del p.(Val345del) causing a severe form of OI. Remarkably, only three probands harboring variants in one of the collagen genes have a positive family history of OI. Mosaicism is suspected in two of those families because there were patients whose parents did not exhibit any OI symptoms (Fig. 1, 5805 and 5806).

Figure 1.

Pedigrees of the families that participated in this study and have more than one OI patient. All relevant family members are indicated. Asterisk (*) indicates patients from whom DNA was obtained.

Three probands carried novel homozygous missense variants in BMP1. The proband with the homozygous variant c.688C>G p.(Arg230Gly) had a moderate to severe phenotype and various deformities necessitating dependency on a wheel chair. The second proband and his affected brother harbored a homozygous missense variant c.691G>T p.(Asp231Tyr) and had a milder phenotype with few fractures and mild deformities (Fig. 1, 5815). The third proband with a homozygous missense variant, c.818C>T p.(Ala273Val), had the most severe phenotype with more than 100 fractures and severe mobility‐limiting deformities.

Alterations causing defects in collagen modification

A novel homozygous nonsense variant, c.976C>T p.(Gln326*), located in exon 5 of the CRTAP gene, was identified in two probands residing in the same geographical region. This variant resulted in a very severe phenotype, including bone and pectus deformities, multiple recurrent fractures, short stature, and congenital hernia.

Two previously reported homozygous variants were detected in the P3H1 gene, one nonsense variant, c.2041C>T p.(Arg681*) (Pepin et al. 2013), and a splice site variant, c.1080+1G>T (Fig. 1, 968 and 5819). Both variants resulted in a severe OI phenotype, with extremely short stature, short and deformed extremities, and significant mobility impairment (Table 1). Moreover, a family history of neonatal and childhood death was reported.

TMEM38B variants were identified in 12 probands and 9 affected family members (Fig. 1, 5820, 5821, 5826, 5827, 5828, and 5831). A previously reported homozygous exon 4 deletion (21 kb), g.32476_53457delinsATTAAGGTATA, p.(Gly152Alafs*5), was found in 11 probands. One proband was compound heterozygous for this 21 kb deletion and a nonsense variant, c.507G>A p.(Trp169*), located in exon 4. This latter variant is generally associated with a severe early‐onset form of OI characterized by bowing of the limbs and multiple fractures, mostly of the femur. In addition, some individuals have blue sclerae, bone deformities, and/or dentinogenesis imperfecta, but none have hearing loss (Table 1). We identified a shared haplotype between the 12 probands, indicating that the deletion most likely represents a founder alteration (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Haplotype analysis for the 12 probands with in an intragenic TMEM38B marker and five flanking markers. The green box indicates the intragenic marker D9S2107.

Alterations causing defects in collagen folding and cross‐linking

A novel homozygous small genomic deletion was identified in exon 3 of the SERPINH1 gene, c.314_325del p.(Glu105_His108del). This in‐frame deletion caused the loss of four amino acid residues and resulted in a moderate to severe phenotype in an 18 months old proband presenting with blue sclerae, joint hypermobility, pectus deformity, osteopenia, and multiple recurrent fractures, in addition to general growth and developmental delay (Table 1).

Three different homozygous variants in the FKBP10 gene were identified in four probands. The previously described nonsense variant c.1330C>T p.(Gln444*) segregated in four patients of the same family (Fig. 1, 5835). A novel splice site variant, c.391+4A>T, was identified in two probands originating from the same city, which indicates that the families could be related. The pedigree of the family containing eight patients harboring the splice site variant is presented in Figure 1_5833. mRNA studies revealed an out‐of‐frame skip of exon 2 of the FKBP10 gene (data not shown). A third proband had a novel homozygous frameshift variant, c.1276del p.(Gln426Argfs*10) (Fig. 1, 5836). All affected individuals were diagnosed with Bruck syndrome based on recurrence of long bone fractures and congenital contractures typical of Bruck syndrome. In addition, scoliosis and/or pectus deformities (Table 1) occurred in accordance with previously published data (Alanay et al. 2010; Shaheen et al. 2011; Schwarze et al. 2013).

Alterations causing defects in bone mineralization

In a proband aged 7 years, we identified a homozygous missense variant, c.242C>G p.(Ser81Cys), in exon 3 of the SERPINF1 gene. The patient had recurrent and multiple fractures, but with normal sclerae and teeth (Table 1). The proband responded poorly to bisphosphonate treatment, as reported for patients with SERPINF1‐related OI (Homan et al. 2011; Venturi et al. 2012; Minillo et al. 2014).

Discussion

We performed mutation analysis on a cohort of 49 Palestinian OI families. By using an OI gene panel NGS screening strategy, we identified variants of known OI genes in 41 probands, corresponding to a variant uptake rate of 84%. In contrast to the OI populations studied so far, more than half of the Palestinian OI probands (25/41) have a recessive form of OI due to high rates of consanguinity. Consanguinity was more prevalent in our study population than in the general Palestinian population (65% vs. 39%), indicating ascertainment bias in families with possible recessive genetic disorders (Table 1). Eight probands, of whom six belong to consanguineous families, did not have any disease‐causing variant in the known OI genes, reflecting further genetic heterogeneity in OI.

In total, we identified 28 different variants in nine OI genes, including 10 COL1A1, five COL1A2, three BMP1, three FKBP10, two TMEM38B, two P3H1, one CRTAP, one SERPINF1, and one SERPINH1 (Table 1).

The phenotypes of patients with COL1A1 and COL1A2 variants (Table 1) were in line with previously reported genotype–phenotype correlations, with haploinsufficiency resulting in milder phenotypic abnormalities and pathogenic missense variants causing more severe phenotypes (Gentile et al. 2012; Vandersteen et al. 2014). However, the novel splice site variant c.3531+1G>T is associated with moderate phenotypic features, which is at odds with an earlier report that this variant resulted in mild OI (Willing et al. 1994).

We identified three novel homozygous BMP1 missense variants affecting highly conserved amino acids located in the catalytic metalloprotease domain, which may thus interfere with the enzymatic activity of the BMP1/tolloid‐like protein. Hitherto, four BMP1 missense variants have been reported (Asharani et al. 2012; Martinez‐Glez et al. 2012; Valencia et al. 2014; Cho et al. 2015; Syx et al. 2015). Two of them, c.747C>G p.(Phe249Leu) and c.808A>G p.(Met270Val), are in the same domain as the variants we identified (Fig. S1) and it diminishes BMP1/mTLD proteolytic activity, resulting in impaired secretion of the protein (Martinez‐Glez et al. 2012; Cho et al. 2015). The phenotypes of those two patients were severe in accordance with the phenotype of our patient harboring the c.818C>T p.(Ala273Val) variant. Nevertheless, the other two patients harboring the c.688C>G p.(Arg230Gly) and c.691G>T p.(Asp231Tyr) variants have a moderate and a mild phenotype, respectively (Table 1). Highly variable phenotypes associated with BMP1 variants have been recently reported (Pollitt et al. 2016), but further investigation of the correlating molecular pathogenesis is needed. In agreement with previous observations (Baldridge et al. 2008), both variants of CRTAP and P3H1 caused severe OI (Table 1). Notably, the P3H1 splice site variant c.1080+1G>T has been previously described as the “West African allele’’ (Cabral et al. 2007; Pepin et al. 2013), but it seems to be more widely spread.

Remarkably, we found a recurrent exon 4 deletion p.(Gly152Alafs*5) in TMEM38B in 12 probands, making it the most frequent variant among the Palestinian OI patients. This variant has been reported previously in three Saudi Arabian families (Shaheen et al. 2012) and in three Israeli Arab Bedouin families (Volodarsky et al. 2013). The latter families have the same ancestry as the Palestinian population. Haplotype analysis suggests a founder effect for this particular variant. The genotype–phenotype correlation is in line with the previous reports, so we recommend evaluation of this variant in Palestinian families with moderate AR OI (Table 1).

The SERPINH1 variant reported here is the first in‐frame genomic SERPINH1 deletion to be identified, though its phenotype of moderately severe OI does not differ from the phenotype caused by variants generated by a premature termination codon (PTC) (Christiansen et al. 2010; Duran et al. 2015). Consistent with previous observations (Schwarze et al. 2013), patients with variants in the FKBP10 gene were diagnosed with Bruck syndrome because of congenital contractures. Notably, OI severity varied widely (Table 1).

The proband harboring a SERPINF1 missense variant has a milder phenotype than the patients previously reported (Becker et al. 2011; Homan et al. 2011; Caparros‐Martin et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2013; Minillo et al. 2014; Stephen et al. 2015), possibly because the mutant PEDF protein retains some activity. Although the c.242C>G p.(Ser81Cys) missense variant has been reported as a variant with uncertain clinical significance in the Clinvar database (Variation ID 218613) and with an allele frequency in ExAC of about 0.1%, the amino acid is well conserved and is located directly next to a putative receptor binding site of the PEDF protein (Fig. S2). Missense variants in SERPINF1 were found to underlie otosclerosis in three families (Ziff et al. 2016), but our patient aged 7 years had no hearing impairment.

In conclusion, AR forms of OI are the most prevalent (>60%) in the Palestinian OI population. This finding emphasizes the importance of genetic analysis of AR OI genes in Palestinians with OI in order to reduce the risk of this devastating disorder. A TMEMB38B deletion was found to be the most common variant among the Palestinian OI patients. In eight probands we did not identify any disease‐causing variant in the known OI genes, making them suitable for exome sequencing in order to identify the underlying genetic defects. Such analysis will probably lead to the identification of new OI genes.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. BMP1 catalytic metalloprotease domain.

Figure S2. PEDF homologs and protein structure.

Table S1. Linkage analysis markers.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the OI patients and their families who endlessly supported our research efforts. We also thank the referring physicians Adeeb NaserEddin, Atta Zamari, Ayman Obeidi, Bashar Ahmad, and Moamar Kdemat. We are grateful to Ahmad Thweb, Israr Sabri, Omar Mohammad, Rasha Abu Rahma, and Safaa Sabah for blood sampling. F. M. and B. C. are fellows of the Fund for Scientific Research (FWO). O. E. has a BOF Research Fellowship from the Ghent University. Contract grants include FWO grant number G.0171.05 and Methusalem grant number 08/01M01108 to A. D. P.

Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine 2018; 6(1): 15–26

References

- Alanay, Y. , Avaygan H., Camacho N., Utine G. E., Boduroglu K., Aktas D., et al. 2010. Mutations in the gene encoding the RER protein FKBP65 cause autosomal‐recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86:551–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asharani, P. V. , Keupp K., Semler O., Wang W., Li Y., Thiele H., et al. 2012. Attenuated BMP1 function compromises osteogenesis, leading to bone fragility in humans and zebrafish. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90:661–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaf, S. , and Khawaja M.. 2009. Consanguinity trends and correlates in the Palestinian Territories. J. Biosoc. Sci. 41:107–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldridge, D. , Schwarze U., Morello R., Lennington J., Bertin T. K., Pace J. M., et al. 2008. CRTAP and LEPRE1 mutations in recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 29:1435–1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkova, E. , Mohan U., Chitayat D., Keating S., Toi A., Frank J., et al. 2015. Fetal skeletal dysplasias in a tertiary care center: radiology, pathology, and molecular analysis of 112 cases. Clin. Genet. 87:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. , Semler O., Gilissen C., Li Y., Bolz H. J., Giunta C., et al. 2011. Exome sequencing identifies truncating mutations in human SERPINF1 in autosomal‐recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 88:362–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benusiene, E. , and Kucinskas V.. 2003. COL1A1 mutation analysis in Lithuanian patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Appl. Genet. 44:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodian, D. L. , Chan T. F., Poon A., Schwarze U., Yang K., Byers P. H., et al. 2009. Mutation and polymorphism spectrum in osteogenesis imperfecta type II: implications for genotype‐phenotype relationships. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18:463–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafe, L. , Cormier‐Daire V., Hall C., Lachman R., Mortier G., Mundlos S., et al. 2015. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2015 revision. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 167A:2869–2892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borel, A. , Eichenberger D., Farjanel J., Kessler E., Gleyzal C., Hulmes D. J., et al. 2001. Lysyl oxidase‐like protein from bovine aorta. Isolation and maturation to an active form by bone morphogenetic protein‐1. J. Biol. Chem. 276:48944–48949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers, P. H. , and Pyott S. M.. 2012. Recessively inherited forms of osteogenesis imperfecta. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46:475–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, W. A. , Chang W., Barnes A. M., Weis M., Scott M. A., Leikin S., et al. 2007. Prolyl 3‐hydroxylase 1 deficiency causes a recessive metabolic bone disorder resembling lethal/severe osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Genet. 39:359–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral, W. A. , Ishikawa M., Garten M., Makareeva E. N., Sargent B. M., Weis M., et al. 2016. Absence of the ER cation channel TMEM38B/TRIC‐B disrupts intracellular calcium homeostasis and dysregulates collagen synthesis in recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. PLoS Genet. 12:e1006156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caparros‐Martin, J. A. , Valencia M., Pulido V., Martinez‐Glez V., Rueda‐Arenas I., Amr K., et al. 2013. Clinical and molecular analysis in families with autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta identifies mutations in five genes and suggests genotype‐phenotype correlations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 161A:1354–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. Y. , Ki C. S., Sohn Y. B., Kim S. J., Maeng S. H., and Jin D. K.. 2013. Osteogenesis imperfecta Type VI with severe bony deformities caused by novel compound heterozygous mutations in SERPINF1. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28:1107–1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. Y. , Asharani P. V., Kim O. H., Iida A., Miyake N., Matsumoto N., et al. 2015. Identification and in vivo functional characterization of novel compound heterozygous BMP1 variants in osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 36:191–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, H. E. , Schwarze U., Pyott S. M., Alswaid A., Al Balwi M., Alrasheed S., et al. 2010. Homozygosity for a missense mutation in SERPINH1, which encodes the collagen chaperone protein HSP47, results in severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 86:389–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish, R. 1997. The human type I collagen mutation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:181–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgleish, R. 1998. The human collagen mutation database 1998. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:253–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, F. S. , and Sillence D. O.. 2014. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical diagnosis, nomenclature and severity assessment. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164A:1470–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran, I. , Nevarez L., Sarukhanov A., Wu S., Lee K., Krejci P., et al. 2015. HSP47 and FKBP65 cooperate in the synthesis of type I procollagen. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24:1918–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, R. H. , and Veigel C.. 1996. Calcium uptake and release modulated by counter‐ion conductances in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. Scand. 156:387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlino, A. , and Marini J. C.. 2016. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet 387:1657–1671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbes, L. , Kim K., Riess A., Hoyer‐Kuhn H., Beleggia F., Bevot A., et al. 2015. Mutations in SEC24D, encoding a component of the COPII machinery, cause a syndromic form of osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96:432–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, F. V. , Zuntini M., Parra A., Battistelli L., Pandolfi M., Pals G., et al. 2012. Validation of a quantitative PCR‐high‐resolution melting protocol for simultaneous screening of COL1A1 and COL1A2 point mutations and large rearrangements: application for diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 33:1697–1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan, E. P. , Rauch F., Grafe I., Lietman C., Doll J. A., Dawson B., et al. 2011. Mutations in SERPINF1 cause osteogenesis imperfecta type VI. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26:2798–2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homan, E. P. , Lietman C., Grafe I., Lennington J., Morello R., Napierala D., et al. 2014. Differential effects of collagen prolyl 3‐hydroxylation on skeletal tissues. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keupp, K. , Beleggia F., Kayserili H., Barnes A. M., Steiner M., Semler O., et al. 2013. Mutations in WNT1 cause different forms of bone fragility. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapunzina, P. , Aglan M., Temtamy S., Caparros‐Martin J. A., Valencia M., Leton R., et al. 2010. Identification of a frameshift mutation in Osterix in a patient with recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87:110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lek, M. , Karczewski K. J., Minikel E. V., Samocha K. E., Banks E., Fennell T., et al. 2016. Analysis of protein‐coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536:285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl, K. , Astrom E., Rubin C. J., Grigelioniene G., Malmgren B., Ljunggren O., et al. 2015. Genetic epidemiology, prevalence, and genotype‐phenotype correlations in the Swedish population with osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 23:1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindert, U. , Cabral W. A., Ausavarat S., Tongkobpetch S., Ludin K., Barnes A. M., et al. 2016. MBTPS2 mutations cause defective regulated intramembrane proteolysis in X‐linked osteogenesis imperfecta. Nat. Commun. 7:11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini, J. C. , and Blissett A. R.. 2013. New genes in bone development: what's new in osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98:3095–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini, J. C. , Forlino A., Cabral W. A., Barnes A. M., San Antonio J. D., Milgrom S., et al. 2007. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum. Mutat. 28:209–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E. , and Shapiro J. R.. 2007. Osteogenesis imperfecta:epidemiology and pathophysiology. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 5:91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez‐Glez, V. , Valencia M., Caparros‐Martin J. A., Aglan M., Temtamy S., Tenorio J., et al. 2012. Identification of a mutation causing deficient BMP1/mTLD proteolytic activity in autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 33:343–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza‐Londono, R. , Fahiminiya S., Majewski J., Canada C., Tetreault M., Nadaf J., et al. 2015. Recessive osteogenesis imperfecta caused by missense mutations in SPARC. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 96:979–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minillo, R. M. , Sobreira N., De Faria Soares M. D. E., Jurgens J., Ling H., Hetrick K. N., et al. 2014. Novel deletion of SERPINF1 causes autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta type VI in two Brazilian families. Mol. Syndromol., 5:268–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchenko, M. V. , Stetler‐Stevenson W. G., Trubetskoy O. V., Gacheru S. N., and Kagan H. M.. 1996. Metalloproteinase activity secreted by fibrogenic cells in the processing of prolysyl oxidase. Potential role of procollagen C‐proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 271:7113–7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepin, M. G. , Schwarze U., Singh V., Romana M., Jones‐Lecointe A., and Byers P. H.. 2013. Allelic background of LEPRE1 mutations that cause recessive forms of osteogenesis imperfecta in different populations. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 1:194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt, R. C. , Saraff V., Dalton A., Webb E. A., Shaw N. J., Sobey G. J., et al. 2016. Phenotypic variability in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta caused by BMP1 mutations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 170:3150–3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyott, S. M. , Pepin M. G., Schwarze U., Yang K., Smith G., and Byers P. H.. 2011. Recurrence of perinatal lethal osteogenesis imperfecta in sibships: parsing the risk between parental mosaicism for dominant mutations and autosomal recessive inheritance. Genet. Med. 13:125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, F. , Fahiminiya S., Majewski J., Carrot‐Zhang J., Boudko S., Glorieux F., et al. 2015. Cole‐Carpenter syndrome is caused by a heterozygous missense mutation in P4HB. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 96:425–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach, M. , and Giunta C.. 2012. Recessive osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical, radiological, and molecular findings. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 160C:175–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarze, U. , Cundy T., Pyott S. M., Christiansen H. E., Hegde M. R., Bank R. A., et al. 2013. Mutations in FKBP10, which result in Bruck syndrome and recessive forms of osteogenesis imperfecta, inhibit the hydroxylation of telopeptide lysines in bone collagen. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, R. , Al‐Owain M., Faqeih E., Al‐Hashmi N., Awaji A., Al‐Zayed Z., et al. 2011. Mutations in FKBP10 cause both Bruck syndrome and isolated osteogenesis imperfecta in humans. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 155A:1448–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, R. , Alazami A. M., Alshammari M. J., Faqeih E., Alhashmi N., Mousa N., et al. 2012. Study of autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta in Arabia reveals a novel locus defined by TMEM38B mutation. J. Med. Genet. 49:630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry, S. T. , Ward M. H., Kholodov M., Baker J., Phan L., Smigielski E. M., et al. 2001. dbSNP: the NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:308–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirdah, M. M. 2014. Consanguinity profile in the Gaza Strip of Palestine: large‐scale community‐based study. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 57:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, J. , Girisha K. M., Dalal A., Shukla A., Shah H., Srivastava P., et al. 2015. Mutations in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta from consanguineous Indian families. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 58:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, C. , Dott B., Roth M. P., and Alembik Y.. 1989. Birth prevalence rates of skeletal dysplasias. Clin. Genet. 35:88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symoens, S. , Syx D., Malfait F., Callewaert B., de Backer J., Vanakker O., et al. 2012. Comprehensive molecular analysis demonstrates type V collagen mutations in over 90% of patients with classic EDS and allows to refine diagnostic criteria. Hum. Mutat. 33:1485–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symoens, S. , Malfait F., D'Hondt S., Callewaert B., Dheedene A., Steyaert W., et al. 2013. Deficiency for the ER‐stress transducer OASIS causes severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta in humans. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8:154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symoens, S. , Barnes A. M., Gistelinck C., Malfait F., Guillemyn B., Steyaert W., et al. 2015. Genetic defects in TAPT1 disrupt ciliogenesis and cause a complex lethal osteochondrodysplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97:521–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syx, D. , Guillemyn B., Symoens S., Sousa A. B., Medeira A., Whiteford M., et al. 2015. Defective proteolytic processing of fibrillar procollagens and prodecorin due to biallelic BMP1 mutations results in a severe, progressive form of osteogenesis imperfecta. J. Bone Miner. Res. 30:1445–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadmouri, G. O. , Nair P., Obeid T., Al Ali M. T., Al Khaja N., and Hamamy H. A.. 2009. Consanguinity and reproductive health among Arabs. Reprod. Health 6:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia, M. , Caparros‐Martin J. A., Sirerol‐Piquer M. S., Garcia‐Verdugo J. M., Martinez‐Glez V., Lapunzina P., et al. 2014. Report of a newly indentified patient with mutations in BMP1 and underlying pathogenetic aspects. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164A:1143–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandersteen, A. M. , Lund A. M., Ferguson D. J., Sawle P., Pollitt R. C., Holder S. E., et al. 2014. Four patients with Sillence type I osteogenesis imperfecta and mild bone fragility, complicated by left ventricular cardiac valvular disease and cardiac tissue fragility caused by type I collagen mutations. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 164A:386–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venturi, G. , Gandini A., Monti E., Dalle Carbonare L., Corradi M., Vincenzi M., et al. 2012. Lack of expression of SERPINF1, the gene coding for pigment epithelium‐derived factor, causes progressively deforming osteogenesis imperfecta with normal type I collagen. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27:723–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volodarsky, M. , Markus B., Cohen I., Staretz‐Chacham O., Flusser H., Landau D., et al. 2013. A deletion mutation in TMEM38B associated with autosomal recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum. Mutat. 34:582–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warman, M. L. , Cormier‐Daire V., Hall C., Krakow D., Lachman R., Lemerrer M., et al. 2011. Nosology and classification of genetic skeletal disorders: 2010 revision. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 155A:943–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willing, M. C. , Pruchno C. J., and Byers P. H.. 1993. Molecular heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta type I. Am. J. Med. Genet. 45:223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willing, M. C. , Deschenes S. P., Scott D. A., Byers P. H., Slayton R. L., Pitts S. H., et al. 1994. Osteogenesis imperfecta type I: molecular heterogeneity for COL1A1 null alleles of type I collagen. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 55:638–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. , Ichimura A., Qian N., Iida T., Yamazaki D., Noma N., et al. 2016. Mice lacking the intracellular cation channel TRIC‐B have compromised collagen production and impaired bone mineralization. Sci. Signal. 9:ra49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff, J. L. , Crompton M., Powell H. R., Lavy J. A., Aldren C. P., et al. 2016. Mutations and altered expression of SERPINF1 in patients with familial otosclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25:2393–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. BMP1 catalytic metalloprotease domain.

Figure S2. PEDF homologs and protein structure.

Table S1. Linkage analysis markers.