Abstract

Objective/Hypothesis

Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) is a simple, inexpensive device-driven exercise therapy. Therapeutic potential of EMST was examined among head and neck cancer survivors with chronic radiation-associated aspiration.

Study Design

Retrospective case series.

Methods

Maximum expiratory pressures (MEPs) were examined among n=64 radiation-associated aspirators (per Penetration-Aspiration Scale, PAS, score ≥6 on modified barium swallow, MBS). Pre-post EMST outcomes were examined in a nested subgroup of patients (n=26) who enrolled in 8 weeks of EMST (25 repetitions, 5 days/week, 75% load). Non-parametric analyses examined effects of EMST on the primary endpoint maximum expiratory pressures (MEPs). Secondary measures included swallowing safety (Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swall0wing Toxicity, DIGEST), perceived dysphagia (M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory, MDADI), and diet (Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients, PSSHN).

Results

Compared to sex matched published normative data, MEPs were reduced in 91% (58/64) of HNC aspirators (mean±SD: 89±37). Twenty-six patients enrolled in EMST; three withdrew. MEPs improved on average 57% (87±29 to 137±44 cm H2O, p<0.001) among 23 who completed EMST. Swallowing safety (per DIGEST) improved significantly (p=0.03). Composite MDADI scores improved post-EMST (pre: 59.9±17.1, post: 62.7±13.9, p=0.13). PSSHN diet scores did not significantly change.

Conclusions

MEPs were reduced in chronic radiation-associated aspirators relative to normative data, suggesting that expiratory strengthening could be a novel therapeutic target to improve airway protection in this population. Similar to findings in neurogenic populations, these data also suggest improved expiratory pressure generating capabilities after EMST and translation to functional improvements in swallowing safety in chronic radiation-associated aspirators.

Keywords: Aspiration, radiation, expiratory muscle strength training, head and neck cancer

INTRODUCTION

Chronic aspiration is a potentially life threatening manifestation of radiation-associated dysphagia (RAD), estimated to occur in up to 31% of long-term head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors treated with curative wide-field chemoradiotherapy.1 Aspirators are 4.6 times more likely to develop pneumonia after CRT than non-aspirators, 2 and pneumonia confers 42% increased risk of mortality.3 A recent SEER-Medicare analysis suggests the population-level lifetime risk of aspiration pneumonia after chemoradiation is 24%3, representing a significant 2.7-fold increased risk over non-cancer controls. While it can be argued that this risk estimate might be inflated as a reflection of community treatment in older Medicare beneficiaries (≥65 years of age), a similar risk estimate (cumulative incidence of 20% at 3 years) was reported from the long-term follow-up of a dysphagia-optimized IMRT trial with radiation therapy planning that specifically constrained dose to the uninvolved larynx and pharyngeal constrictors suggesting the persistence of this problem in modern practice even with more conformal radiotherapy in younger patients2. Despite notable refinements in swallow therapy over the last 3 decades, attempts to reverse aspiration with swallowing therapy are often disappointing. For instance, penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) scores were virtually identical among 125 patients enrolled in a multi-site clinical trial of intensive (60 reps/BID for 3 months) home exercise with or without neuromuscular electrical stimulation (pooled pre-post PAS comparison p>0.05).

Expiratory muscle strength training (EMST) is a simple, inexpensive device-driven exercise therapy.4 During EMST, a patient expires forcefully into a one-way spring loaded valve that can be tightened incrementally to increase resistance of the exercise task to strengthen recruited muscles over time. For patients with swallowing impairment, EMST is thought to act on one of two mechanisms to improve airway protection: 1) strengthening subglottic expiratory pressure generating forces, translating to a stronger cough to clear aspirate from the lower airway,5 or 2) improving airway closure for swallowing by exercise of swallowing-related muscles such as those in the submental suprahyoid region.6–9 Trials examining a progressive-resistive exercise paradigm of EMST in patients with or at risk for dysphagia related to neurogenic pathologies (i.e., Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and stroke) report improvement in airway protection after a 5-week strengthening exercise program (detailed summary in Table I).5,8–10 EMST is accordingly gaining popularity among various populations with swallowing disorders but, to our knowledge, results of EMST have not published in patients with radiation-associated aspiration. Thus, the purpose of this case series was to examine the therapeutic potential of EMST among head and neck cancer (HNC) survivors with chronic radiation-associated aspiration. We hypothesized that expiratory force generating capacity (i.e., maximum expiratory pressures, MEPs) and swallowing safety (i.e., penetration/aspiration as measured by Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity, DIGEST) would improve after 8-weeks of EMST.

Table I.

Review of EMST series in dysphagia or dysphagia at-risk populations

| Study Details | Feasibility | MEPS | Swallowing measures |

Cough measures |

PROs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitts et al., (2009)5 | n=10 Single arm prospective trial PD with MBS detected pen/asp EMST: 4 weeks 75% MEPs | Program completion rate: 100% Adherence: NR AE: NR | Pre: 108.22 ±23.2 Post: 135.9 ±37.5 Δ (%): 27.68 (+26%) p=0.005 | PAS: mean Δ −2.1, p=0.001 | Voluntary cough compression phase duration Δ −53%, p<0.001, expiratory phase rise time Δ−40%, p<0.001 | NR |

| Troche et al., (2010)8 | n=68 2-arm sham controlled RCT PD with or without dysphagia EMST: 5 weeks 75% MEPs | Program completion rate: 88% Adherence: NR AE: NR | NR | PAS: mean Δ −0.57, p = 0.021 Hyoid displacement: p<0.05 | NR | SWAL-QOL: significantly improved p=0.007 independent of treatment group (EMST v sham) |

| Plowman, et al. (2016)7 | n=15 Single arm delayed intervention trial ALS with or without dysphagia EMST: 5 weeks (50% MEP), weekly home visit with clinician | Program completion rate: 79% Adherence: NR AE: None | Pre: 63 (49–80) Post-lead in: 57 (40–74) Post-EMST: 75 (52–99) Δ (%): +17.17 (31.6% ) p= 0.01 | PAS: NS Hyoid: Δ+57mm post-EMST, p=0.03 | Voluntary cough spirometry: NS | NR |

| Wheeler-Hegland et al. (2016)10 | n=14 Single arm trial ≥3-months post ischemic stroke EMST: 5 weeks (60% MEP), weekly home visit with clinician | Program completion rate: 86% Adherence: NR AE: None | Pre: 71.2±28.8 Post: 103.7±43.8 Δ (%): 32.5 (45%) p= 0.001 | PAS: Δ-1 (p>0.05) MBSImp: Δ-5 post-EMST (p<0.001) | Self-reported urge to cough: Δ+1 (p=0.28) post-EMST) Reflexive (not voluntary) cough improved: cough volume acceleration (Δ+15, p=0.03), PEFR (L/s, Δ+1.06, p=0.006) | NR |

| Park et al., (2016)9 | n=32sham controlled RCT dysphagic subacute (≤6 mos.) stroke patients EMST: 4 weeks (70% MEP) | Program completion rate: 79% Adherence: NR AE: None | NR | Submental swallowing sEMG: Δ+19%, p<0.001 PAS liquid/solid: Δ-1.1, p<0.001 FOIS: Δ+0.9, p<0.001 | NR | NR |

NR = not reported; NS = not statistically significant (p>0.05); MEPs = maximum expiratory pressure; PROs = Patient reported outcomes; PD = Parkinson’s disease; MBS = modified barium swallow; PAS = Penetration-Aspiration Scale.

METHODS

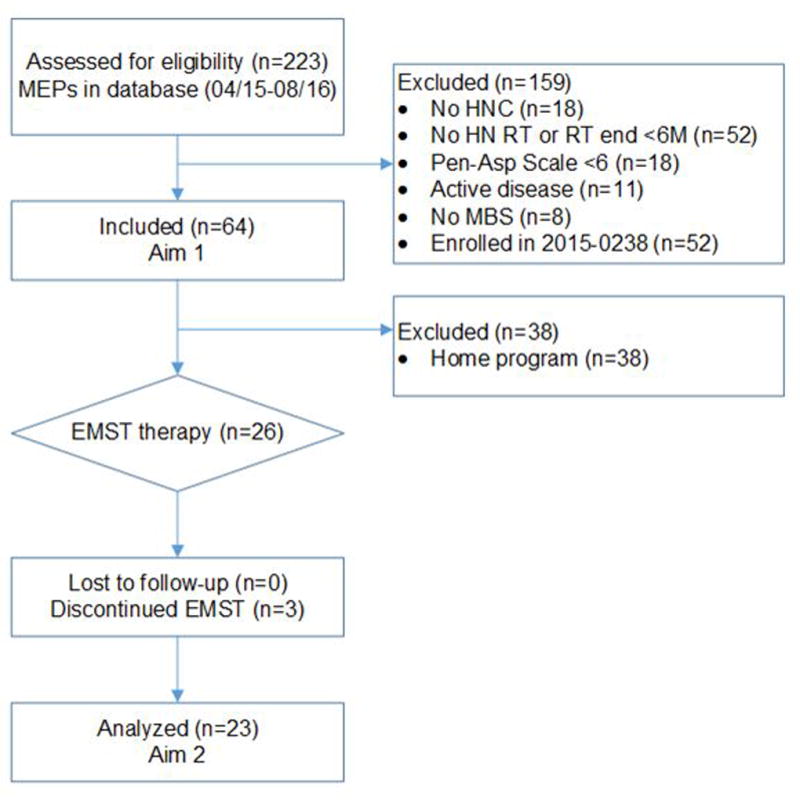

This retrospective case series examined MEPs among all radiation-associated aspirators (per maximum Penetration-Aspiration Scale [PAS] score ≥6 on modified barium swallow [MBS]) who completed expiratory testing April 2015 to August 2016. Pre-post EMST outcomes were examined in a nested series of patients (n=26) who enrolled in 8-weeks of EMST in the first year offering a EMST therapy program in the Head and Neck Center at MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC). EMST was performed per published protocols and consisted of: 25 repetitions, 5 days per week with the EMST trainer calibrated at 75% of individualized MEP.8 This analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained. An adapted CONSORT diagram depicts the study follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adapted CONSORT flowchart

Excluded patients in MEPS database who are enrolled in prospective cohort study 2015-0238 that is currently accruing patients to prospectively validate the results of this retrospective case series.

Expiratory Muscle Strength Training (EMST)

The EMST protocol is described according to the “TIDieR” guide (Template for Intervention Description and Replication).11 Prior to EMST, MEPs were measured using a digital manometer (Micro Respiratory Pressure Meter, CareFusion, Yorba Linda, California). For each trial, the participant was instructed to inhale to total lung capacity (“fill your lungs as much as possible”), seal the lips fully around a flanged mouthpiece and exhale forcefully (“blow out as fast and as hard as you can”). MEP was calculated as the average of three trials within 10% variance. The EMST150™ device (Aspire Products, Gainesville, Florida) was used for training. The training load was set weekly at 75% of individualized MEP. Expiratory tasks were completed standing with a nose clip in place. During EMST, participants were asked to take a deep breath, hold the cheeks lightly with the thumb and forefingers, and blow forcefully through the device until the valve opens (hearing air rush out). Patients were instructed to train on a 5-5-5 schedule (5 sets of 5 breaths on 5 days of the week).8 Clinicians then verified independent, accurate technique with EMST before the patient left clinic to begin the home program; none required caregiver assistance. Patients returned to clinic weekly to test MEPs, to recalibrate EMST trainers to reflect 75% of the current MEP and to ensure patients were tolerating the treatment and performing exercises correctly. A licensed speech pathologist (SLP) provided face-to-face weekly sessions in the outpatient Head and Neck Center at MDACC. Patients were provided written instructions and carried out home practice with the EMST device between weekly clinic sessions with the SLP.

Feasibility, Safety, and Adherence

Program completion rate was derived by counting the number of patients who withdrew (i.e., dropped out of therapy) before completing the 8-week program. Medical records and therapy notes were reviewed for adverse events. Adherence was self-reported at each clinic visit. Participants were prescribed a 5-5-5 training schedule for 8 weeks totaling 1,000 breaths through the trainer (25 breaths per day, 125 breaths per week). For the purpose of this report, patients reporting >900 breaths through the EMST device during the program were coded as “fully adherent”, ≤900 breaths were coded as “partially adherent”.

Swallowing Evaluation

Swallowing evaluations prior to therapy included a standardized MBS study using a protocol previously described,12 the M.D. Anderson Dysphagia Inventory (MDADI),13 and Performance Status Scale for Head and Neck Cancer Patients (PSSHN).14 Post-EMST swallowing evaluations included the same procedures and were attempted to be scheduled immediately at the end of the 8-week therapy program. MBS studies were reviewed by a blinded trained laboratory rater who previously met published reliability standards using the Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) and the Modified Barium Swallowing Impairment Profile (MBSImP).

DIGEST

DIGEST is a validated staging tool to grade the severity of pharyngeal dysphagia based on results of an MBS study.12 DIGEST first assigns two component scores: 1) safety classification and 2) efficiency classification. To derive the safety classification, the rater assigns the maximum PAS score observed across a series of standard bolus trials with a modifier applied to account for the frequency and amount of penetration/aspiration events. To derive the efficiency classification, the rater assigns an estimation of the maximum percentage of pharyngeal residue on an ordinal scale (<10%, 10–49%, 50–90%, and >90%) with modifiers to assign a pattern of residue across bolus types. The summary DIGEST rating aligns with NCI’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events framework for toxicity reporting in oncology trials, and is based on the interaction of the safety and efficiency classification (grade 0=no pharyngeal dysphagia, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=life threatening). In a validation study of 100 HNC patients, intra-rater reliability was excellent (weighted Kappa=0.82–0.84) with substantial to almost perfect agreement between raters (weighted Kappa=0.67–0.81). Criterion validity was established relative to MBSImP™©15 (r=0.77) and (Oropharyngeal Swallow Efficiency16 (r=−0.56).

MBSImP™©

The MBSImP™© is a validated standardized measure that rates physiologic components of the oropharyngeal swallow. MBSImP™© ratings for pharyngeal phase components were calculated by review of the entire MBS video recording and included: soft palate elevation, laryngeal elevation, anterior hyoid excursion, epiglottic movement, laryngeal vestibule closure, pharyngeal stripping wave, pharyngeal contraction, pharyngoesophageal segment opening, tongue base retraction, and pharyngeal residue. Each component is rated using a 3 to 5-point ordinal scale in which 0 indicates no impairment. An overall pharyngeal impairment MBSImp score was calculated as the sum of the 10 component measures, providing a continuous score (range: 0 to 28) for which higher ratings indicate greater physiologic impairment.15

PSSHN

Diet levels were rated according to the PSS-HN Normalcy of Diet subscale, in which 0 indicates “non-oral nutrition” and 100 represents “full oral nutrition without restrictions”.14 The PSS-HN was rated per semi-structured interview by the SLP conducting the MBS study.

MDADI

The MDADI was administered by written questionnaire upon arrival for MBS studies. The MDADI is a 20-item questionnaire that quantifies an individual’s global (G), physical (P), emotional (E), and functional (F) perceptions of swallowing-related quality of life. The MDADI has been validated with regard to content, criterion and construct validity and is considered reliable based on test-retest correlations (0.69–0.88) and overall Cronbach’s coefficient = .96.13 The composite MDADI score summarizes overall performance on 19-items of the MDADI (excluding global). All MDADI scores are normalized to range from 20 (extremely low functioning) to 100 (high functioning).13

Statistical Analysis

Non-parametric analyses were performed to examine pre- to post-EMST change in the primary endpoint (MEPs), and for secondary measures including DIGEST, maximum PAS, MDADI, and PSSHN Normalcy of Diet. Effect size was calculated and compared to thresholds detected using distributional methods including Minimal Clinically Important Difference (MCID = .5 standard deviation)17 and 95% confidence interval Minimal Detectable Change ( ).18,19 With 23 evaluable subjects, the study had 90% power to detect effect size of 0.71 with two-sided α=0.05. For the primary endpoint of MEPs, we had >99% power to detect the observed ΔMEP of 49.05 (standard deviation: 28.8) with two-sided α=0.05. For the secondary endpoint of DIGEST safety grade, we had 64% power to detect the observed effect size of 0.64. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata Data Analysis software version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and power calculations via G*Power version 3.1.9.2 (Heinrich-Heine Unversitat Dusseldorf, Germany).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Sixty-four disease-free HNC survivors were included. Mean age was 65 and 86% were male. The majority of patients had a history of multimodality cancer treatment, and more than half were treated for oropharyngeal primary tumors. Mean time post-cancer treatment was 96 months. Clinical and demographic characteristics were similar among all aspirators reviewed and the subgroup of 26 patients who participated in the EMST therapy. Table II summarizes clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

Table II.

Sample characteristics

| All (n=64) |

EMST therapy subgroup (n=26) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median Age (range) | 67 (40–88) | 67 (52–76) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 55 (85.9%) | 23 (88.5%) |

| Female | 9 (14.1%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| T-classification | ||

| 0–2 | 21 (32.8%) | 8 (30.8%) |

| 3–4 | 22 (34.4%) | 11 (42.3%) |

| Unknown | 3 (4.7%) | 1 (3.8%) |

| Recurrent | 13 (20.3%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Multiple primaries | 5 (7.8%) | 2 (7.7 %) |

| HNC site | ||

| OPC | 40 (62.5%) | 17 (65.4%) |

| HP/Lx | 8 (12.5%) | 5 (19.2%) |

| Nasopharynx | 2 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) |

| Thyroid | 2 (3.1%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| UP | 6 (9.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Salivary gland | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Multiple primaries | 5 (7.8%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Therapeutic combo | ||

| CRT | 42 (65.6%) | 18 (69.2%) |

| RT | 2 (3.1%) | 1 (3.9%) |

| RT/CRT + Salvage Surgery | 9 (14.1%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| Re-RT | 3 (4.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Surgery + PORT/POCRT | 8 (12.5%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Surgery | ||

| Neck | 12 (18.8%) | 5 (19.2%) |

| Primary | 7 (10.9%) | 3 (11.5%) |

| Primary + Neck | 11 (17.2%) | 4 (15.4%) |

| None | 34 (53.1%) | 14 (53.9%) |

MEP’s in Chronic Aspirators

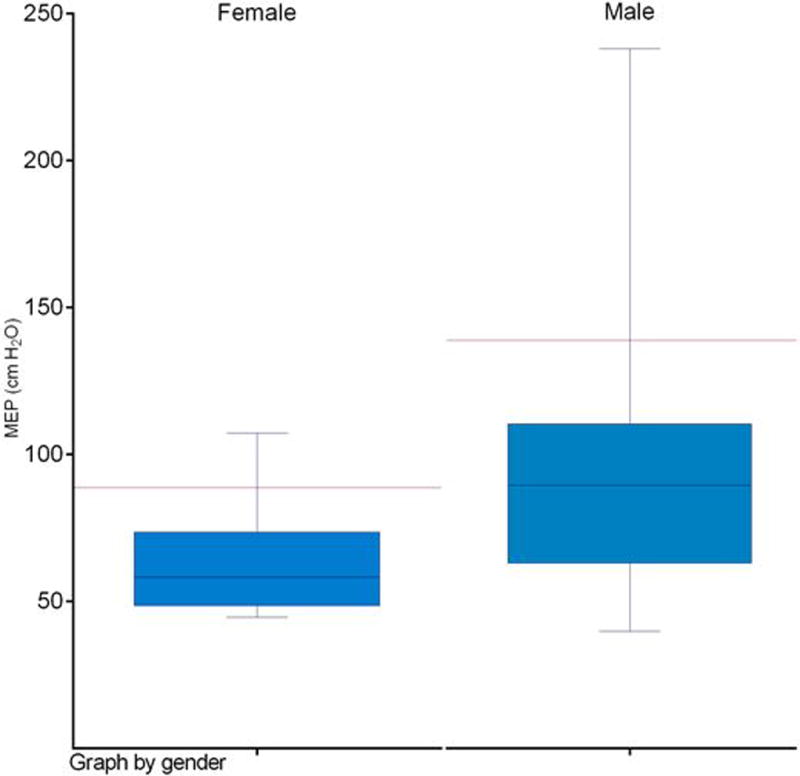

Average MEPs were 89.0 cm H2O (standard deviation: 36.9) among all 64 chronic aspirators tested. MEPs were reduced relative to established sex-matched normative data in 91% (58/64) of patients as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Maximum expiratory pressures (MEPs) among n=64 aspirators by sex

Red bar denotes lower limit of normal range by sex per published normative data.

EMST Therapy

Twenty-six aspirators enrolled in EMST, 96% of whom had MEPs below normative ranges. Three withdrew from EMST before completing the 8-week program, yielding a program completion rate of 88%. Reasons for withdrawal included dizziness during training in 1 patient and hospitalization for aspiration pneumonia in 2 patients. Among the 23 patients who completed all 8-weeks of the program, 91% self-reported full adherence with the prescribed 5-5-5 training schedule, and the remaining 9% reported partial adherence. All patients who completed the EMST program returned for a swallowing evaluation.

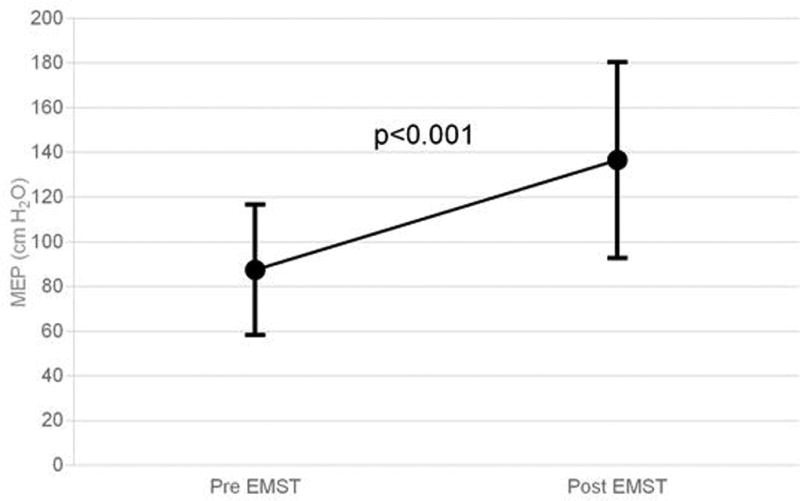

Pre-Post EMST MEP’s

MEPs improved, on average, 57% (87±29 to 137±44 cm H2O, p<0.001, MCID: 14.6, MDC: 16.8) among the 23 patients who completed the 8-week EMST program (Figure 3). Thirty-six percent of patients with below normal pre-EMST MEPs achieved MEP’s within normal sex-matched range after EMST.

Figure 3.

Maximum expiratory pressures (MEPS) among n=23 patients pre- and post-EMST

MEPs improved by 57% (0<0.001) after 8 weeks of expiratory muscle strength training.

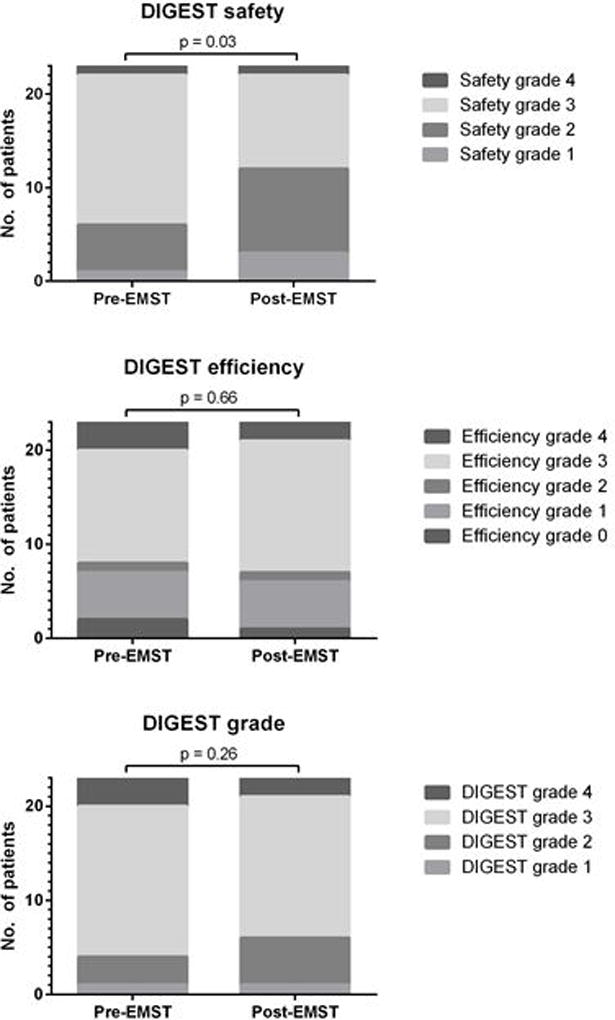

Pre-Post EMST Swallowing Outcomes

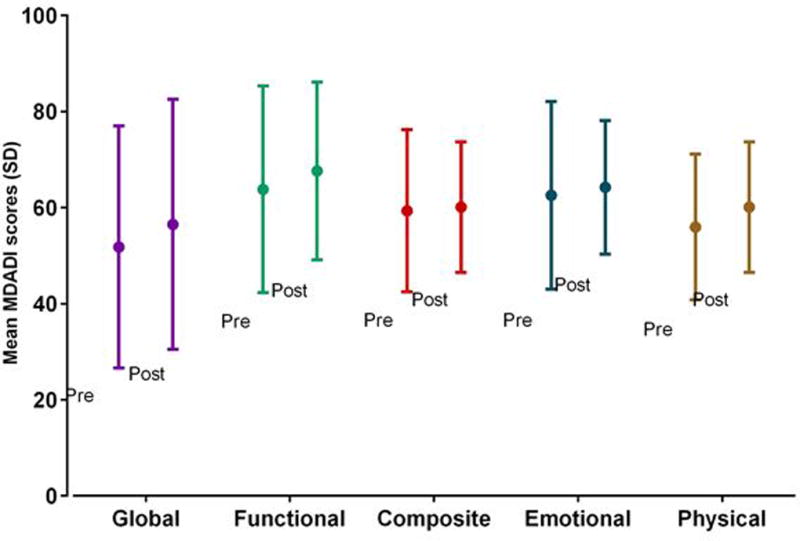

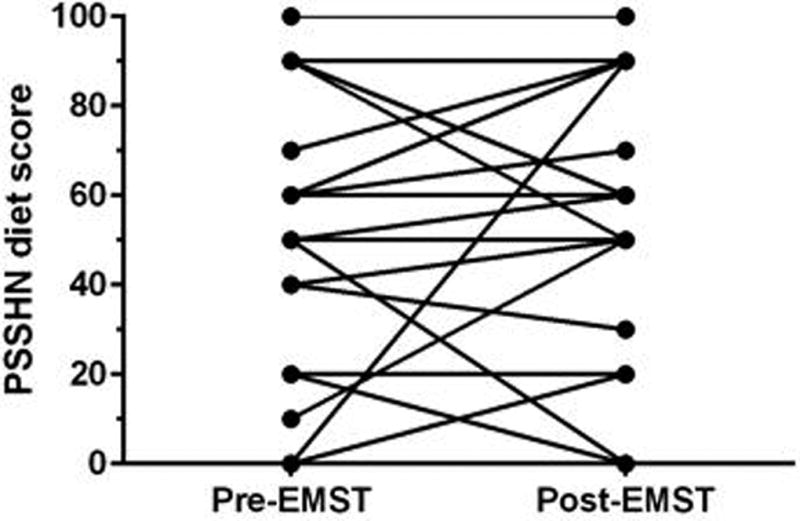

Prior to EMST, most patients had severe dysphagia. Pre-EMST, 74% had grade ≥3 DIGEST safety impairment on MBS representing repeated aspiration (PAS score 7–8 on multiple consistencies and/or on ≥50% of thin liquid trials), and 48% had poor MDADI scores (composite <60). Pre-EMST, MBSImP™© components 8 (laryngeal elevation), 9 (anterior hyoid), and 15 (tongue base retraction) were abnormal (score>0) in all patients with mean MBSImP™© Pharyngeal Impairment total 16.6 (SD: 4.8). After EMST, DIGEST safety classification improved a full grade in 30% of patients (p = 0.03, Figure 4a). Among the 7 patients with improved DIGEST safety classification, 4 had less frequent high grade airway invasion (PAS 7–8) and 3 had improved expectoration of high grade penetration/aspiration. DIGEST efficiency classification (p=0.66, Figure 4b) and summary pharyngeal grade (p=0.26, Figure 4c) did not significantly change. Distribution of maximum PAS scores did not significantly change (Pre: PAS6 = 4.4%, PAS7 = 30.4%, PAS8 = 65.2%; Post: PAS5 = 4.4%, PAS6 = 13.0%, PAS7 = 21.7%, PAS8 = 60.9%, p=0.59). MBSImP™© total (mean: 16.9, SD: 4.8) and individual component scores did not significantly change (p>0.05) after EMST. Composite MDADI improved post-EMST (pre: 59.9±17.1, post: 62.7±13.9, p=0.13, Figure 5). PSSHN diet scores did not significantly change after EMST (p=0.37, Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Videofluoroscopy DIGEST grades among n=23 patients pre- and post-EMST

Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST) improved significantly in the safety domain (p=0.03, left), but did not improve in the efficiency domain (p=0.66, middle) or the summary DIGEST (p=0.26, right).

Figure 5.

MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory swallowing-related QOL scores among n=23 patients pre- and post-EMST

MDADI improvements after EMST were not statistically significant in any domain (p>0.05).

Figure 6.

MD Anderson Dysphagia Inventory swallowing-related QOL scores among n=23 patients pre- and post-EMST

Diet levels did not significantly improve after EMST (p=0.37)

DISCUSSION

Chronic aspiration is an exceedingly challenging clinical problem after head and neck radiotherapy. MBS-detected aspiration after chemoradiation is associated with 37% risk of pneumonia,2 and aspiration pneumonia is the leading cause of non-cancer related deaths in long-term survivors20. Chronic aspirators are typically offered swallowing therapy directed by a speech pathologist. The most common therapies provided in modern practice include swallow exercises intended to strengthen the tongue, larynx, and pharynx, training in compensatory strategies, and/or application of neuromuscular electrical stimulation intended to enhance strengthening exercise regimens.21,22 Yet, reports suggest little change in MBS detected aspiration after these standard therapies.23,24 Herein, we report retrospective analysis of functional changes after clinical implementation of a standardized EMST program in HNC survivors with chronic aspiration after radiotherapy. After 8 weeks of EMST, we observed significantly improved MEPs (subglottic expiratory force generating capacity) and MBS-detected swallowing safety (per DIGEST), but non-significant changes in swallowing QOL (per MDADI), MBS-detected swallowing efficiency (per DIGEST), and diet (per PSSHN).

Dysphagia research has increasingly considered downstream targets in the respiratory system to improve airway protection in dysphagic populations and populations at risk for aspiration (such as those with progressive neurodegenerative conditions like PD and ALS).7,8 In this case series of HNC survivors with chronic aspiration, we observed the MEPs improved by 57% among those who completed 8-weeks of a resistance exercise in the EMST therapy program. These gains compare favorably to the typical 30–45% improvement in MEPs reported in neurogenic trials (see Table 1). Gains in MEPs can be conceptualized as stronger subglottic expiratory force generating capacity, and may translate to stronger cough to expel aspiration when it occurs.4 While we are optimistic regarding the potential clinical benefit of improving MEPs in post-radiation aspirators, we did not measure cough in the clinical setting and therefore cannot directly assess at this time whether EMST positively impacted cough function to clear aspiration following completion of EMST. Cough measures are collected in our currently enrolling prospective feasibility trial.

Swallowing parameters also improved after the EMST program. Improvements in MDADI scores represent better swallowing-related quality of life after EMST. While improvements in MDADI failed to reach statistical significance, the most notable gain was in the physical subscale scores. Physical domain scores are computed from items pertaining to the perceived work of eating or dysphagia symptoms encountered during meal time (e.g., “I cough when I drink liquids” and “swallowing takes great effort”). Thus, improvement in the Physical MDADI domain suggests that rather than impacting on psychosocial domains like coping and adaptation (that would be expressed in the Emotional and Functional MDADI subscales), some patients perceive improved ease of swallowing that may reflect modulation of swallowing mechanics after EMST therapy. The patterns of change on MBS may offer insight into the nature of this physical change. Detailed kinematic analyses or other functional studies will be required in future efforts to characterize physiologic profiles of dysphagia best indicated for EMST and to determine what physical parameters are changing in the swallow of patients who respond to EMST25. Using MBS-derived DIGEST classification of swallow safety and efficiency of pharyngeal bolus transport, only swallow safety significantly improved after EMST whereas swallow efficiency did not significantly improve. The DIGEST safety grade essentially denotes the pattern of penetration-aspiration events across the entire MBS study, whereas the efficiency grade estimates the pattern of pharyngeal residue across various bolus types. This finding underscores the potential transference of EMST targeted to swallowing safety or airway protection, meaning that EMST might have a complementary role in dysphagia therapy in the HNC survivor population who also typically have impaired swallowing efficiency and will likely require additional therapies to help efficiency.

It is difficult to compare the nature of the change in swallowing measures in this study to those published in other dysphagia or dysphagia at-risk populations (Table I). Perhaps the most notable distinction in this case series compared to related published trials pertains to dysphagia status. That is, we only included HNC survivors with aspiration (PAS≥6) whereas all but two EMST trials targeting airway protection5,9 included disease-specific populations (e.g., PD, ALS, stroke) at risk for dysphagia but did not mandate dysphagia or abnormal PAS as a requirement for entry into the trial. Thus, other published trials comprise a large proportion of patients without MBS detectable dysphagia or mild dysphagia, whereas our population is comprised of 74% with severe MBS-confirmed chronic RAD making any gains likely noteworthy. Acknowledging limitations comparing populations with neurologic disease to HNC survivors, common observations after EMST in other populations include significantly improved MEPs,5,7,8 improved penetration/aspiration on MBS,5,8,9 and improved swallowing-related hyolaryngeal function7–9 after EMST. While we initially targeted patients with overt airway protection impairment (i.e., PAS≥6), there might be a role for earlier intervention with HNC survivors who have lesser degree of impairment (e.g., PAS 3–5) but risk progressive deterioration of swallow function over years of survivorship. This premise of early or proactive EMST in aspiration at-risk populations of HNC survivors requires examination in subsequent studies, and the population of patients with lower-grade dysphagia were not studied in this series.

Swallowing-related airway protection is exceedingly complex, coupling sensorimotor processes to prevent airway entry during the swallow and those that promote clearance of aspirate from the airway via a timely and effective cough. A framework for this continuum of airway protection behaviors and their common neural substrates has been proposed.26 EMST focuses on strengthening mechanisms of airway protection and defense. Recently, Martin-Harris and colleagues27 have described a novel skill training paradigm using respiratory/swallow biofeedback to train chronic radiation-associated aspirators to swallow at the optimal phase of respiration (during expiration at mid and low lung volume). Impressively, they observed >30% reduction in MBS detected aspiration events with significantly improved respiratory-swallow phase patterning and laryngeal vestibule closure within 8 sessions of training that maintained at 1 month follow-up (among patients enrolled with sensate aspiration, PAS score 6–7). Respiratory strength training might offer an alternate or complementary skills training paradigm that leverages a respiratory activity to improve airway protection.

Observations from this case series suggest therapeutic potential for EMST in HNC survivors with chronic radiation-associated aspiration. As hypothesized, we detected significant gains in MEPs (primary endpoint) and swallowing-related outcomes (secondary endpoint) following 8 weeks of EMST calibrated at a 75% load. Others have studied 5 week paradigms at 50% to 75% MEP. We elected to initially introduce an 8 week training program in our HNC clinic to optimize chances of achieving hypertrophic changes because of the refractory nature of aspiration in this population in response to other exercise-based therapeutic efforts.23,28 We acknowledge inherent limitations of a retrospective case series, foremost including lack of a control group. Lack of formal pulmonary function testing and cough measurements further limits our ability to characterize baseline pulmonary status as well as the translation of improved MEPs to airway clearance mechanisms or actual risk of pneumonia. The reader is cautioned not to over-interpret the therapeutic potential of EMST in this population. EMST is not expected to reverse aspiration for the majority of patients, but in 30% of patients was associated with less frequent aspiration events or better clearance. Future studies will be necessary to examine whether this and stronger MEPs equates to a risk reduction in aspiration pneumonia. Yet, we are optimistic that observed gains reflect therapeutic gains because numerous authors have demonstrated modest (at best) effects of exercises in chronic post-radiation dysphagic populations (>3–6 months post head and neck radiotherapy). We did not directly assess transference of improved subglottic expiratory force generating capacity to stronger cough, and this requires further evaluation in the HNC population. These results represent preliminary hypothesis generating foundational data that require prospective validation.

CONCLUSIONS

MEPs were reduced relative to normative data in chronic radiation-associated aspirators, suggesting that expiratory strengthening could be a novel therapeutic target to improve airway protection in this population. Similar to findings in other populations, these preliminary data also suggest that improvement in expiratory pressure generating capabilities after EMST translated to functional improvements in airway safety and patient’s perceived swallowing abilities in survivors with chronic radiation-associated aspiration. We are currently conducting an IRB-approved prospective pilot trial to explore efficacy of EMST for radiation-associated dysphagia.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosures and Conflicts of Interest: This work with accomplished with support of the MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant Program Survivorship Seed Monies Award. Dr. Hutcheson receives funding support from the National Cancer Institute (R03CA188162-01). Drs. Hutcheson, Lai, and Fuller receive funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248-01). Dr. Fuller has received speaker travel funding from Elekta AB.

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented at the International American Head and Neck Society 9th International Conference on Head and Neck Cancer in Seattle, WA, USA, July 18th, 2016.

References

- 1.Feng FY, Kim HM, Lyden TH, et al. Intensity-modulated chemoradiotherapy aiming to reduce dysphagia in patients with oropharyngeal cancer: clinical and functional results. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2732–2738. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter KU, Lee OE, Lyden TH, et al. Aspiration pneumonia after chemo-intensity-modulated radiation therapy of oropharyngeal carcinoma and its clinical and dysphagia-related predictors. Head Neck. 2014;36:120–125. doi: 10.1002/hed.23275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu B, Boero IJ, Hwang L, et al. Aspiration pneumonia after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2015;121:1303–1311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sapienza C, Troche M, Pitts T, Davenport P. Respiratory strength training: concept and intervention outcomes. Semin Speech Lang. 2011;32:21–30. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1271972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pitts T, Bolser D, Rosenbek J, Troche M, Okun MS, Sapienza C. Impact of expiratory muscle strength training on voluntary cough and swallow function in Parkinson disease. Chest. 2009;135:1301–1308. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wheeler-Hegland KM, Rosenbek JC, Sapienza CM. Submental sEMG and hyoid movement during Mendelsohn maneuver, effortful swallow, and expiratory muscle strength training. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2008;51:1072–1087. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plowman EK, Watts SA, Tabor L, et al. Impact of expiratory strength training in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 2016;54:48–53. doi: 10.1002/mus.24990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troche MS, Okun MS, Rosenbek JC, et al. Aspiration and swallowing in Parkinson disease and rehabilitation with EMST: a randomized trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1912–1919. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fef115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park JS, Oh DH, Chang MY, Kim KM. Effects of expiratory muscle strength training on oropharyngeal dysphagia in subacute stroke patients: a randomised controlled trial. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43:364–372. doi: 10.1111/joor.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hegland KW, Davenport PW, Brandimore AE, Singletary FF, Troche MS. Rehabilitation of swallowing and cough functions following stroke: an expiratory muscle strength training trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2016;97:1345–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014;348:g1687. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutcheson KA, Barrow MP, Barringer DA, et al. Dynamic Imaging Grade of Swallowing Toxicity (DIGEST): Scale development and validation. Cancer. 2016;123:62–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: the M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.List MA, Ritter-Sterr C, Lansky SB. A performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;66:564–569. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<564::aid-cncr2820660326>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin-Harris B, Brodsky MB, Michel Y, et al. MBS measurement tool for swallow impairment-MBSImp: establishing a standard. Dysphagia. 2008;23:392–405. doi: 10.1007/s00455-008-9185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, Logemann JA, Shanahan TK. Oropharyngeal swallow efficiency as a representative measure of swallowing function. J Speech Hear Res. 1994;37:314–325. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3702.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norman GR, Sloan JA, Wyrwich KW. The truly remarkable universality of half a standard deviation: confirmation through another look. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2004;4:581–585. doi: 10.1586/14737167.4.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazis LE, Anderson JJ, Meenan RF. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989;27:S178–189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copay AG, Subach BR, Glassman SD, Polly DW, Jr, Schuler TC. Understanding the minimum clinically important difference: a review of concepts and methods. Spine J. 2007;7:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szczesniak MM, Maclean J, Zhang T, Graham PH, Cook IJ. Persistent dysphagia after head and neck radiotherapy: a common and under-reported complication with significant effect on non-cancer-related mortality. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2014;26:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krisciunas GP, Sokoloff W, Stepas K, Langmore SE. Survey of usual practice: dysphagia therapy in head and neck cancer patients. Dysphagia. 2012;27:538–549. doi: 10.1007/s00455-012-9404-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crary MA, Carnaby-Mann GD, Faunce A. Electrical stimulation therapy for dysphagia: descriptive results of two surveys. Dysphagia. 2007;22:165–173. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langmore SE, McCulloch TM, Krisciunas GP, et al. Efficacy of electrical stimulation and exercise for dysphagia in patients with head and neck cancer: A randomized clinical trial. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E1221–1231. doi: 10.1002/hed.24197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazarus CL, Husaini H, Falciglia D, et al. Effects of exercise on swallowing and tongue strength in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer treated with primary radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43:523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutcheson KA, Hammer MJ, Rosen SP, Jones CA, McCulloch TM. Expiratory muscle strength training evaluated with simultaneous high resolution manometry and electromyography. Laryngoscope. 2017 Jan 13; doi: 10.1002/lary.26397. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Troche MS, Brandimore AE, Godoy J, Hegland KW. A framework for understanding shared substrates of airway protection. Journal of applied oral science : revista FOB. 2014;22:251–260. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720140132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin-Harris B, McFarland D, Hill EG, et al. Respiratory-swallow training in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:885–893. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burkhead LM, Sapienza CM, Rosenbek JC. Strength-training exercise in dysphagia rehabilitation: principles, procedures, and directions for future research. Dysphagia. 2007;22:251–265. doi: 10.1007/s00455-006-9074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]